Abstract

Context

An aging population leads to a growing demand for long-term services and supports (LTSS). In 2002, France introduced universal, income-adjusted, public long-term care coverage for adults 60 and older, whereas the United States funds means-tested benefits only. Both countries have private long-term care insurance (LTCI) markets: American policies create alternatives to out-of-pocket spending and protect purchasers from relying on Medicaid. Sales, however, have stagnated, and the market's viability is uncertain. In France, private LTCI supplements public coverage, and sales are growing, although its potential to alleviate the long-term care financing problem is unclear. We explore whether France's very different approach to structuring public and private financing for long-term care could inform the United States’ long-term care financing reform efforts.

Methods

We consulted insurance experts and conducted a detailed review of public reports, academic studies, and other documents to understand the public and private LTCI systems in France, their advantages and disadvantages, and the factors affecting their development.

Findings

France provides universal public coverage for paid assistance with functional dependency for people 60 and older. Benefits are steeply income adjusted and amounts are low. Nevertheless, expenditures have exceeded projections, burdening local governments. Private supplemental insurance covers 11% of French, mostly middle-income adults (versus 3% of Americans 18 and older). Whether policyholders will maintain employer-sponsored coverage after retirement is not known. The government's interest in pursuing an explicit public/private partnership has waned under President François Hollande, a centrist socialist, in contrast to the previous center-right leader, President Nicolas Sarkozy, thereby reducing the prospects of a coordinated public/private strategy.

Conclusions

American private insurers are showing increasing interest in long-term care financing approaches that combine public and private elements. The French example shows how a simple, cheap, cash-based product can gain traction among middle-income individuals when offered by employers and combined with a steeply income-adjusted universal public program. The adequacy of such coverage, however, is a concern.

Keywords: long-term care, aging, insurance, comparative study, social welfare

Policy Points.

France’s model of third-party coverage for long-term services and supports (LTSS) combines a steeply income-adjusted universal public program for people 60 or older with voluntary supplemental private insurance.

French and US policies differ: the former pay cash; premiums are lower; and take-up rates are higher, in part because employer sponsorship, with and without subsidization, is more common–but also because coverage targets higher levels of need and pays a smaller proportion of costs.

Such inexpensive, bare-bones private coverage, especially if marketed as a supplement to a limited public benefit, would be more affordable to those Americans currently most at risk of “spending down” to Medicaid.

America's population is aging, and with it, the need for long-term services and supports (LTSS) is rapidly growing. A recent estimate projected a 5-fold increase in LTSS spending by 2050, up from the estimated $203 billion to $243 billion spent on it in 2009.1 Unfortunately, few middle-aged and older Americans have considered how they will obtain the supportive services they will need if they experience disability, chronic disease, or cognitive impairment,2 which is highly probable, given the 69% likelihood among those 65 and older of requiring functional assistance before they die.3 That is, they will no longer be able to independently perform at least one personal care task, such as bathing, dressing, toileting, or housekeeping, and they may need help taking medications or leaving their homes. Yet saving against such costs is difficult because of their unpredictability. While some Americans 65 or older will be able to rely on unpaid help from spouses, adult children, or others, many others rely on paid support. But those potential LTSS costs are highly variable. Even though nearly 60% of older Americans will incur either no costs or lifetime costs of less than $10,000, 1 in 6 will have costs of $100,000 or more, and 1 in 25 will have costs of $250,000 or more.3 This highly skewed distribution in long-term care expenditures suggests that financing is best addressed through risk sharing, that is, through insurance—public, private, or a combination of both.

Although in theory Americans favor private solutions to social problems, private long-term care insurance (LTCI) has not lived up to its promise. Market penetration has plateaued at about 12.4% of Americans age 65 and older.4 Even though private LTCI pays for roughly 7% of total LTSS expenditures, this statistic has stayed flat for some time,5 and policyholders are increasingly likely to be higher-income individuals rather than those at greatest financial risk from LTSS expenses,6 who are seemingly deterred by the high cost and complexity of the products. Moreover, the supply side of the LTCI market is suffering from a deep decline, with many companies reducing business or leaving the market altogether,6 as well as taking steps that will likely reduce the market even further, through premium increases, stricter underwriting, and gender pricing. Nor has government successfully provided alternative solutions: the Community Living Assistance Services and Supports (CLASS) Act, introduced under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), was repealed in January 2013. A year earlier, Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius had halted implementation because key design features of the federally administered, voluntary long-term care insurance program made it highly vulnerable to adverse selection, which, in turn, precluded a long-term actuarial guarantee of solvency, as required by law.7

In our search for alternative models of financing LTSS, we looked outside the United States, specifically at France, whose little-discussed long-term care (LTC) system is unusual in how it mixes public and private financing and has encouraged the development of a private LTCI market. Although the United States also relies heavily on combinations of public and private funds to pay for LTSS, the relationship between public and private is very different in the 2 countries: in the United States, private funds are the first resort—older Americans rely on their own resources or private insurance until these are exhausted and the public system takes over. In France, public benefits are universally available to people age 60 and older, although only the poor receive the full benefit (as well as safety net supports through local government). The benefit is heavily income adjusted and varies according to the severity of the disability. Thus, private funding supplements public funding in France rather than the other way around, as in the United States. Supplemental private funding for LTSS in France comes primarily from the services users’ (or family members’) income and savings, and it may also come from private LTCI, known as “dependency insurance.”

Compared with that of the United States, France's private LTCI market is more successful, at least in the ratio of actual to potential private LTCI purchasers, with approximately 5.7 million policyholders in 2012 (just over 11% of French people 18 and older).8,9 (In contrast, the United States had 7.3 million policyholders in 2010, about 3% of the adult population.4,10) Moreover, the French market is growing at a steady rate of 5% per year in 2012,8 whereas the US market has stagnated, with the number of covered lives remaining essentially flat since 2005.4 However, while coverage is broad and growing, private LTCI currently pays only an estimated 0.5% of total LTC expenditures in France, due to both the low average benefits and the fact that the market's rapid expansion over the last decade means that few policyholders have reached the point of claiming benefits.

The French situation is unique among highly developed Western nations, making it particularly relevant to the United States. Only Israel and Singapore have robust private LTCI markets (in Israel, this is because it is often bundled with other forms of supplementary health insurance, and in Singapore, coverage is mandated by the government for all workers).11 Elsewhere, experts have seen little potential for private LTCI.12 Instead, a preference for universal public insurance has meant that several European countries (eg, Germany and the Netherlands) and East Asian countries (eg, South Korea and Japan) have adopted such programs.13 To understand whether the United States might learn from the French model, we investigated the factors leading to the expanding market in France.

Background

Private LTCI in France cannot be discussed without understanding how it complements the public financing system for LTSS. In France, private LTCI wraps around the publicly financed universal cash benefit for dependent elderly persons age 60 and older. This benefit, the APA (Allocation personnalisée d'autonomie, translated as the “Personal autonomy allowance”), was established in 2002. One of its notable features is its income-adjusted design, which creates incentives for supplementation, much as Medicare coverage gaps have spurred sales of Medigap supplemental insurance in the United States.

The APA

Introduced in 2002, the APA is a universal benefit for French people 60 or older needing LTSS. It is steeply income adjusted: recipients at the highest income level (€2,927.66 [$3,981.62] or more per month, about 3.5% of recipients) must pay a 90% coinsurance, while the poorest 23% (those with monthly incomes of €734.66 [$999.14] or less) have no cost-sharing requirements.14 Cost sharing depends on income only; asset limits and estate recovery provisions do not apply. (Proposals to introduce such provisions have poor prospects, largely because the program that the APA replaced, the Prestation spécifique dépendance [PSD], had poor take-up largely due to estate recovery provisions.)

Benefits are also determined by an individual's assessed level of need. A nationally standardized assessment methodology sorts beneficiaries into 6 GIR (Groupe iso-ressources) levels according to the AGGIR (Autonomie gerontologie groupes iso-ressources) grid, based on their need for assistance with activities of daily living such as bathing, eating, and toileting, as well as for needs resulting from cognitive impairment. GIR 1 and 2 levels are considered “severe” dependency, and GIR levels 3 and 4 “partial” dependency (see Table 1). The GIR group, along with income level, determines benefit levels.

Table 1.

Monthly Full Benefit for Community-Based APA Recipients, 2013

| GIR Level | Level of Dependency | Amount in Euros (dollars) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Severe: must be bed- or chair-bound and require constant access to help; at the end of life | €1,304.84 ($1,774.58) |

| 2 | Severe: must be bed- or chair-bound and require daily assistance several times a day, or require constant monitoring owing to cognitive impairment | €1,118.43 ($1,521.07) |

| 3 | Partial: requires assistance with transferring and mobility, as well as bathing and dressing | €838.82 ($1,140.80) |

| 4 | Partial: requires some help with transferring, bathing, and dressing | €559.22 ($760.54) |

APA beneficiaries are limited in how they can use their cash benefit (as well as their income-adjusted coinsurance requirement). It must be used in accordance with a care plan prescribed by locally managed geriatric assessment teams, which focus primarily on aide services. Beneficiaries also must prove that they spent their APA funds on prescribed services, report whom they hire (and they may employ family members other than spouses), and comply with employment regulations under tax, labor, and immigration laws. Compliance is enforced and rewarded with employer tax breaks by having beneficiaries use a “universal service employees check,” a voucher system (Chèques emploi service universel, or CESU) that is used for a variety of domestic workers reimbursed under government programs, including the APA. It deducts workers’ pay from beneficiaries’ bank accounts, into which APA benefits are directly deposited.

Private LTCI

As we noted previously, the French market for private LTCI is large and growing, with approximately 5.7 million policyholders in 2012. Most of this growth, however, is in group (employer-based) products, which constitute 75% of policies sold.8 For about 6% of policies overall, employers mandate coverage and pay premiums for active employees, a virtually unheard-of practice in the United States for LTCI.

The policies themselves differ from those sold in the United States. They tend to offer less coverage and subsequently are cheaper; they also are simpler and easier to administer, from the claimant's perspective. They pay out a defined cash benefit rather than the US practice of reimbursing claimants for services purchased up to a fixed daily benefit (dollar) cap. The average annual premium in 2010 was €345 ($469) (€29 per month, or $39).8 This figure has remained relatively stable over the past few years and contrasts significantly with the average US premium of $2,283.15 Coverage can be even less expensive (an average €322 [$438] per year) if the contract covers only “severe” dependency, which about two-thirds do, a more stringent eligibility requirement than is usual in the United States (see Table 1, although insurers rely on activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living measures in addition to the GIR, to maintain independence from the government system of assessing eligibility). Contracts that cover “partial” as well as severe dependency cost about 25% more, or €403 ($548) per year. Vesting periods for individual coverage tend to be long: purchasers must pay premiums for a full year before becoming eligible for benefits on the basis of physical disability due to disease, and 3 years for cognitive impairment. All plans typically impose a 90-day waiting period before benefits can be paid, triggered by the qualifying disability. Average monthly payouts are €540 ($734), typically paid in cash: €563 ($766), on average, for those with a “severe” dependency and €292 ($397) for those with a “partial” dependency.

Employer-based policies can be even cheaper: the typical premium averages €74 ($101) annually, with 40% to 50% of the cost borne by the employer. Average monthly benefits are €150 ($204) per month. This lower cost makes sense, given the average age at enrollment (40 to 44), as opposed to 60 to 62 for individually purchased coverage. There is typically no underwriting for such plans, although employees with disabilities sufficient to trigger coverage are not allowed to enroll under the plans’ terms and conditions. In addition, a small number of employers enroll employees in compulsory plans that are fully subsidized by the employer. While premium costs per enrollee are lowered by eliminating the potential for adverse selection and coverage takes effect immediately, employees generally receive benefits without having to contribute to premiums only if they are employed when they become disabled. To continue their coverage post-retirement, they must pay all or part of the premium, although the relatively low cost of doing so means that such coverage tends to be highly affordable.

Rather than offering policies along the US model, many French employers offer defined contribution options (sometimes based on the number of years of service) that can be converted to annuities triggered by disability; pension plan upgrades that double pension payments in the event of disability, in exchange for slightly lower pension benefits; or the option to continue payment into a defined benefit option at the group insurance rate. The advantage of the first 2 options is that once they have retired, enrollees need not make further contributions, thus eliminating the problem of lapsing premium contributions. In contrast, like the third French option, US group policies require a consistent premium contribution history in order for enrollees to be eligible for benefits. Moreover, in the United States, participants must submit bills to the insurer for reimbursement rather than receive a fixed benefit, as in France—a far less administratively complex arrangement.

Table 2 shows the 3 types of private insurers that offer private LTCI in France16: private for-profit insurance companies, mutual societies, and provident societies, each regulated separately. Although for-profit insurers dominate the individual market, mutual societies have the largest market share by dominating the group market; they are often tied to a particular profession, such as teaching. These nonprofit organizations (with shareholder policyholders) sell a range of complementary health policies (equivalent to Medigap for Medicare beneficiaries in the United States) that supplement national health insurance and social security (collectively known as sécurité sociale) more generally. Provident societies, which also sell through employers, have the smallest market share. These institutions de prévoyance are a type of mutual society whose membership is based on various professional or other affiliations. About 5 of the 30 companies offering LTCI policies dominate the individual market, representing 73% of insured lives in 2010.17 Table 2 clearly shows that although the mutual societies have the largest market share, for-profit insurers pay out the bulk of benefits. This reflects both the lower level of benefits offered under employer-based plans and the fact that such coverage has expanded rapidly over the last few years. Therefore, as a group, policyholders may be too young to have significant claims.

Table 2.

The Private LTCI Market in France, 2010a

| Individuals Insured | Total Premiums Collected | Total Benefits Delivered | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount in | Amount in | |||||

| Number | millions of euros | millions of euros | ||||

| (millions) | Percentage | (dollars) | Percentage | (dollars) | Percentage | |

| Insurance companiesb | 1.6 | 29 | €403 ($548) | 77 | €150 ($204) | 89 |

| Mutual societies | 3.6 | 65 | €97 ($132) | 18 | ||

| Provident societies | 0.3 | 6 | €25 ($34) | 5 | ||

| €18 ($25)c | 11c | |||||

| Total | 5.5 | 100 | €525 ($714) | 100 | €168 ($229) | 100 |

Data from Fontaine and Zerrar 2013.16

Each insurance type is regulated separately: insurance companies under the “Code d'assurance,” mutual societies under the “Code de la mutualité,” and provident societies under the “Code de la sécurité sociale.”

Aggregate data for mutual and provident societies.

The reasons for purchasing LTCI differ in France from those cited in the United States. In France, purchasers are principally middle-class homeowners of modest means, many of whom are self-employed or are unionized workers, such as teachers and municipal employees who buy group policies through their workplace.18 Managers and other professionals are less likely to purchase LTCI because, according to French insurers, they can self-insure through life insurance or by using home equity.19 Purchase appears to be motivated by the desire to protect family members from the need to provide care; to protect a healthy spouse from the costs associated with a disabled spouse's need for LTSS; and to leave a bequest to family members—what French researchers Courbage and Roudault20 label “altruistic” motives. Accordingly, being married or having children is associated with greater likelihood of purchasing private LTCI. Other predictors of private LTCI purchase are having had previous experience with disability, dependency, chronic disease, or serious illness, whether it has affected the respondent or another family member. In contrast, American purchasers of LTCI tend to be better-off: more than half (57%) had annual incomes of more than $75,000 and 79% had more than $100,000 in liquid assets.21 Key predictors of LTCI purchase are having a college or higher degree; engaging in financial planning for retirement; and having a close relative who needed paid long-term care.21 Thus in France, the primary motivation for purchase seems to be greater awareness of and wanting to protect other family members from the adverse consequences of having a relative with significant uninsured care needs. In the United States, however, evidence for this motivation is lacking, despite much research, and other explanations for purchase (or, rather, nonpurchase) appear to be more important.22–24

Adequacy of Coverage

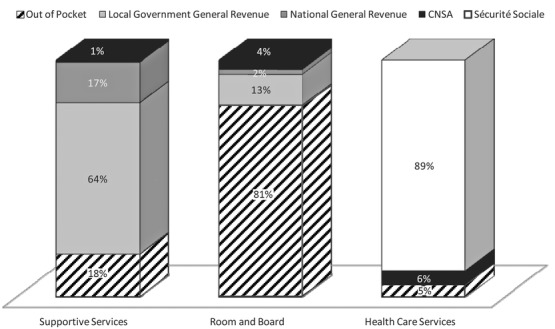

Our description shows that even with supplementary private insurance, the French receive a fairly bare-bones level of coverage. Le Bihan and Martin25 estimated that dependency costs average €2,500 ($3,400) per month (€3,500 [$4,760] in cases of “severe” dependency). They compared this with an average payout of €500 ($680) from the APA and €300 ($408) from private LTCI. Thus, the APA and supplemental insurance together cover €800 ($1,088), or only about 32% of the average monthly cost of care, leaving the poor reliant on safety-net programs operated at the département level, and the remainder drawing on private resources. (Figure 1 shows how LTSS is financed: For example, 64% of the costs for supportive services are paid by local government, 18% out of pocket, and the remainder by the national government and the CNSA [Caisse nationale de solidarité pour autonomie, or National Solidarity Fund for Autonomy], a fund devoted specifically to programs serving older people. Local government funds both local safety-net programs, which cover room and board in residential facilities for elders who cannot afford it, and the APA, which does not cover room and board. Indeed, the départements contribute 78% of APA funding, with only 22% coming from national government.26)

Figure 1.

Funding Sources for the 3 Primary Components of LTSS Spending in France, 2010Data from Fragonard 2011.26The CNSA (Caisse nationale de solidarité pour autonomie, or National Solidarity Fund for Autonomy) is a special national fund that supports programs for older people. Sécurité sociale funds the French national health insurance and retirement programs.

Thus the APA benefit seems inadequate, although there is admittedly little agreement on what adequacy might mean and how the line between public and private responsibility should be drawn. In the United States, private LTCI marketing promotes policies covering the full cost of nursing home care for 3 to 5 years. But those who can afford such policies are also likely to be able to afford at least the cost of room and board. Moreover, even though US private insurers prefer to sell such high levels of coverage, they are increasingly unwilling to do so on a “lifetime” basis. So, in regard to both affordability to purchasers and acceptable financial risk to insurers, there appears to be a trade-off between benefit amounts and the time period over which these benefits are guaranteed. If making such a trade-off is necessary, moderate-income individuals whose retirement income is needed to cover living expenses may find policies offering modest benefits to cover the cost of home-delivered services (along the lines of the limited front-end coverage offered under the APA) more affordable than policies paying out the larger sums needed to cover residential care.

France has 3 types of residential elder care. The highest level, typically attached to hospitals, the equivalent of subacute units, include unité de soins de longues durées (USLD) and specialized facilities serving people with Alzheimer's or other conditions. The French equivalents of nursing homes are établissements d'hébergement pour personnes âgées dépendantes (EHPAD, formerly and colloquially known as maisons de retraite). France also has a lower level of residential elder care termed foyers et logements avec services (housing with services), which offer services such as congregate meals, housekeeping, and transportation, but not personal care. In such residential settings, costs fall into 3 categories: housing, supportive services, and health care. Figure 1 shows how the different service categories are funded:24 health care costs are mostly covered under sécurité sociale, which funds France's national health insurance and retirement programs, while dependency costs (ie, the cost of supportive services) are covered to a greater or lesser extent by the APA.

The cost of room and board in residential facilities can be a significant burden on nonaffluent elders and their families, as it is estimated to range from €1,200 ($1,632) to €2,300 ($3,128) per month.27 A reported 81% of such costs are paid out of private LTCI, savings, retirement income, or family funds, as seen in Figure 1.28 Indeed, the average French retiree's monthly income of €1,300 ($1,768) per month (€1,007 [$1,370] for women, €1,618 [$2,201] for men) barely covers such costs in the least expensive facility, much less other expenses not covered by health insurance and the APA.29 For those who cannot cover these costs from income and savings (including home equity), locally run, means-tested social assistance is available. Families may also be liable for these costs. Unlike the US Medicaid program, such assistance does not have provisions protecting spouses from becoming impoverished. Indeed, France still has “family responsibility” laws that require an elder's descendants (including children, grandchildren, and even great-grandchildren) to contribute to the costs of an elder's institutional care. Although family responsibility is seen as widely ignored and inconsistently implemented by local authorities, it reportedly acts as a deterrent to poor elders’ willingness to receive institutional care, and President François Hollande has vowed to eliminate it.30

Moreover, not everyone who wants to supplement APA coverage with private LTCI is able to do so. French insurers, like their US counterparts, often prevent people with preexisting health conditions from purchasing insurance, even through employers’ plans. Roughly 30% of those who inquire are discouraged from applying for LTCI, and an estimated 15% to 20% of applicants are rejected.31

LTCI Market Penetration in France

To some extent, the level of LTCI market penetration achieved in France stems from its role as a supplement to the APA program: the individual market grew by 40% from 2002 to 2012.8,32 The introduction of the APA stimulated the purchase of private LTCI, especially because the income-adjusted benefit structure provided an incentive to buy supplemental insurance to cover the required coinsurance. It thus is important to understand how and why the APA came into being and continues to enjoy broad public support.

Reasons for Supporting the APA

Public awareness of the issues posed by age-related dependency is higher in France than it is in the United States, among both ordinary people and policy elites. From an American perspective, the attention that high-level policymakers in France have paid to this issue is remarkable: for example, early in his presidency (2007), former president Nicolas Sarkozy referred to dependency as the “fifth [social security] risk” (in addition to health insurance, workers’ compensation coverage, old age pensions, and support for families), a term that is now widely recognized. In 2011, he followed this with a national address on the aging of the French population and the need for LTSS financing reform. This was an event unparalleled in the United States, whose presidents rarely address the issue of long-term care financing directly, much less devote an entire speech to it. In their campaigns, both Sarkozy and Hollande vowed to address the issue, although both have been challenged by the task of squeezing additional public monies out of an already strained system.

Of course, politicians are unlikely to expend political capital on an issue that does not resonate with the voting public. A 2011 poll found that 79% of the French worry about financing long-term care for themselves, and 84% are concerned about financing the long-term care needs of family members.33 These results show, incidentally, the importance in France of framing dependency and long-term care as a family rather than an individual risk. In contrast, only about 40% of Americans surveyed reported being worried about how they will pay for care.34 Moreover, the French survey's results show that 48% of respondents support a public solution to the financing problem; 41% support a mixed public-private solution; and only 9% support an individual solution (2% had no opinion), demonstrating a high level of public awareness and widespread support for a public role.

The APA also benefited from an event that highlighted the need for action and strengthened public support for the program. Shortly after the APA was implemented, the heat wave of 2003 resulted in an estimated 15,000 excess deaths among older people in France,35 most of whom were people needing LTSS. (In addition to age, primary risk factors for death were chronic disease, isolation, and limited mobility.36) The societal shame arising from this event led to a public discussion about responsibility for the elderly and, moreover, ensured support for the nationwide sacrifice of a paid annual holiday (called “National Solidarity Day”) to finance the APA. In exchange for an extra day of work, employers contributed an additional 0.3% of revenue to the CNSA.

Explanations for this broad support of policies supporting older people are many: one is that it is consistent with France's overall approach to social policy. Among those who study comparative welfare policy, France's approach is classified variously as maternalistic,37 in which social policy protects women's caregiving roles; as conservative-corporate, in which the family, voluntary organizations, and the market play larger roles than the state38; or as familistic, in which a strong sense of duty and obligation means that care is provided mainly by the family. These ways of characterizing the French welfare state all agree in emphasizing the family role. European research using the familistic classification ranks Germany and Austria as highly familistic (ie, agreeing with the survey item that “the family is important in life”); with France lower on the scale; and the Netherlands, Sweden, and other Nordic countries placed at the bottom.39,40

It is argued that familistic attitudes are associated with less support for public and private LTCI coverage.39,40 That is, when informal elder care is a normative expectation, support for public coverage and voluntary purchase of private coverage is expected to be lower, whereas in states characterized as less familistic, such as Sweden and the Netherlands, support for state-led LTSS and female workforce participation is expected to be higher—as indeed, it is.41 In other states, however, the relationship between familism and the extent of public LTSS programs is not so clear. As Haberkern and Szydlik42 point out, the German example shows that high public support for social insurance coverage of LTSS can coexist with societal norms and public policies supporting unpaid family care (albeit not very generously, on a per capita basis).

Morel43,44 argues that employment policy might supply the missing explanatory piece. On the one hand, the French see the APA as consistent with public policies that guard against a perceived decline in family caregiving. Thus, the program aims to support home care and allow the employment of family members (other than spouses) as caregivers; its design also presupposes a high level of family involvement in care planning and service delivery.41 On the other hand, European policy encourages female labor force participation, thereby maximizing tax revenue. Accordingly, the APA supports the “free choice” of women to provide unpaid informal care (by providing respite), to work for pay outside the home (by paying for formal care), or to be paid to provide informal care.

The APA's ability to boost employment is particularly important to minority groups disproportionately affected by unemployment and social exclusion. France has experienced chronically high rates of unemployment (averaging 9.54% from 1983 through 2010).45 Personal services jobs—which include child care and housekeeping, as well as home care for the elderly and disabled—are seen as a major source of employment and are disproportionately filled by low-skilled, foreign-born workers (as they are elsewhere in Europe).46 Thus, the APA's ability to create jobs for these marginalized groups—jobs that are fully covered by social security and other legal protections—provides a politically important opportunity to integrate them more fully into French society. Expanding employment in this sector also benefits younger people in rural areas with few employment opportunities. This strategy appears to have had some success. For example, the number of personal services workers in France doubled from 2003 to 200847 and is projected to continue increasing.48

France also has institutional drivers of LTSS policy, particularly the balance between national and local government. In the past, local government financed the bulk of LTSS costs, which mainly comprised means-tested funding for residential care as well as limited social services. The capacity to offer such support varies among the départements. It has been particularly weak in areas with the highest proportion of dependent elderly, which also tend to be places whose tax base is eroding because of the out-migration of young people looking for good jobs. Thus, fiscal relief to local government was a primary motive for introducing the APA. But local government continues to play an important role in funding LTSS in general and the APA in particular. By agreement, the costs of the APA were split between the national government and the départements. Although the original agreement was that such costs would be split equally, over time the proportion contributed by national government has slipped to only 22% (due to the ongoing crisis in French finances), exacerbating financial pressure on the départements as well as existing inequalities between better- and worse-off départements. This burden on local government creates ongoing pressure for APA reform.49,50

Reasons for the Growing Sales of Private LTCI

Clearly, private LTCI has benefited from the public discussion surrounding the APA, and it also benefits from the infrastructure created for it. Private insurers gain indirect protection against moral hazard via the public program integrity controls imposed on APA beneficiaries (which apply to private insurance benefits when they are used to meet coinsurance requirements for APA benefits). Consequently, because French insurers have little concern that cash benefits will increase fraud or be used for non-disability-related purposes, they have no need to impose controls on how the money is used. In part this is because eligibility is generally triggered by higher levels of disability.

An important reason for the market's success is the higher rates of voluntary insurance in France, compared with the United States. The French are characterized as highly risk averse.51 For example, their personal savings rate is 15.8%, compared with 4% for Americans (in part due to government policy encouraging savings).47 The French also are more accustomed to purchasing private insurance to supplement public coverage. Just as Medicare beneficiaries in the United States supplement Medicare coverage through Medigap plans, the French use supplemental policies to cover the sizable coinsurance and copayments required under their national health insurance plan. No such parallel exists among younger Americans in the United States, which has no market for private insurance to supplement inadequate employer-sponsored coverage.

Thus, because French people expect to need supplemental private medical insurance at younger as well as older ages, they may be more primed to purchase private insurance to supplement public APA coverage for LTSS. Moreover, French employers often contribute to supplemental medical insurance for their employees, so it also may seem more natural and expected for employers to contribute to supplemental dependency insurance coverage in addition to offering an employer-sponsored group plan.

Another reason for the high rate of private LTCI coverage in France is the wide availability of inexpensive, employer-sponsored (and sometimes employer-subsidized) plans. This is particularly intriguing because employers in other countries have generally declined to subsidize LTCI for their employees. In the United States, only 1% of employees buy employer-sponsored LTCI, and only 0.3% of employers offer it (although this figure rises to 20% among large employer's), and it is rarely subsidized by the employer.52 If a French employee with subsidized coverage leaves for another job, the employer's financial participation ends, but the employee can continue coverage by paying the entire premium. When insurance is provided through a mutual society, in which membership is based on profession, coverage may continue even after a change of job (eg, a teacher switching from one school to another).

When an employee retires, the employer contributions end or decrease. Although the arrangements vary, typically the employer provides a lump sum toward future costs of maintaining the coverage, with the amount keyed to the retiree's length of employment. Even if the employee has to pay all or a greater share of LTCI premiums under a group insurance plan after changing jobs or retiring, employer-sponsored plan premiums are much lower than comparable individual premiums, especially where universal employee coverage is mandated. Moreover, because private insurance premiums are always age rated (based on age at enrollment), maintaining coverage that began at a younger age under employer sponsorship is usually more affordable than buying an individual policy at age 60 to complement the public APA.

The popularity of private LTCI also can be attributed to the policies themselves, which, in contrast to those in the United States, are both affordable and easy to understand. The average annual premium of €345 ($469) in 2010 stands in sharp contrast with the US average of $2,283.8,15 Moreover, would-be purchasers can easily understand the policies. In France, the cost of premiums varies only in age and extent of coverage (whether for “severe” disability only or both “severe” and “partial” disability), unlike the many coverage options offered by US insurers (which offer a dizzying array of choices, such as inflation protection, elimination periods, and maximum coverage durations, a complexity that is partly due to the state-level regulation of insurance products). In addition, the policies operate under simple, well-defined benefit triggers that consumers can understand and relate to and, most important, can be consistently interpreted by claims assessors, underwriters, and actuaries, a characteristic that Menioux53 described as the “cornerstone” of French insurers’ success.

In addition, the benefits are simple: French policies pay out cash, whereas American policies operate under a reimbursement model, which covers approved benefits on a per diem basis only. Thus, the benefit cannot be used as an income supplement, as cash might; the need to purchase services (which may not be fully covered) deters people from claiming; and the per diem basis means that claimants receive payment only when services are used. The US system consequently results in fewer claimants receiving the full benefit amount, compared with policies that pay cash, whether or not paid care is used, as under the French model. American insurers therefore set the price of cash benefits higher, making them less attractive. French insurers, in contrast, prefer the administrative simplicity and lower overhead of cash benefits and price their policies accordingly.

The US reimbursement model, however, adds complexity for purchasers. Potential purchasers in the United States must compare and contrast coverage policies, whether and what kind of home care is covered, for example. The importance of this product simplicity has been emphasized by many observers. Indeed, Malleray54 recommends further simplifying the French market by adopting more uniform definitions of risk and inflation protections. Such recommendations are consistent with a considerable body of literature establishing that complexity in financial products is likely to dampen purchasing behavior.55,56 In France, the industry itself has moved toward broader product simplification, and recent government initiatives are likely to make that movement even more pronounced.57

Long-Term Care Financing Lessons From France: Possibilities and Caveats

France's national health system (ranked best in the world by the World Health Organization in 2000) inspired Victor Rodwin to suggest that France could provide a template for US health reform in the form of a universal public program whose coinsurance requirements leave a major role for supplemental private insurance.58 The 2010 Affordable Care Act adopted a different approach, one that expands access to private insurance, with public coverage (Medicaid) available only to those who cannot afford even subsidized private policies. The United States may similarly choose not to take lessons from the French with respect to financing LTSS for the elderly. Nonetheless, the 2 countries show some surprising parallels: both are unique in having sizable private LTCI markets. The principal difference between the 2 in public LTSS financing is that entitlement coverage in France is steeply income adjusted, whereas in the United States it is strictly means tested. Both countries finance public coverage for LTSS from general revenues rather than through a dedicated “social insurance” mechanism, and both require subnational governments (the states in the United States, the départements in France) to share in financing the programs. Last, in both countries, policy change tends to be incremental rather than sweeping.

Clearly, the United States needs new ideas: witness the Senate-sponsored Long-Term Care Commission's 2013 report, which describes the inadequacy of existing financing arrangements but fails to offer a resolution. The commissioners remain divided between the proponents of a “social insurance” approach (an unlikely prospect in an era so apparently hostile to expanding entitlements) and the proponents of private financing, who appear either unaware of the moribund state of US private LTCI or wrongly ascribe it to the alleged ease with which the undeserving rich can obtain Medicaid LTSS coverage.59,60

In some ways, the United States’ LTCI market can be seen as successful: claimants report high satisfaction with coverage; 4 out of 5 receive home care or assisted living services rather than less desirable nursing home care; and, even when spending on assisted living is excluded, payouts from private LTCI account for 7% of national spending on LTSS.61 Yet, sales have been essentially flat for the past decade, and many insurers have exited the market,6 which is puzzling, given that the only alternatives to private LTCI are self-funding or qualifying for Medicaid LTSS coverage (which requires impoverishment). Why? Research has found that many interested buyers of private LTCI are deterred by its perceived high cost, a perception that recent steep premium increases can only exacerbate. US insurers appear to have chased the top end of the market by offering expensive products that cover both the catastrophic risk of a protracted nursing home stay and the front-end costs of home care at lower levels of disability. Certainly, over the past 20 years, the average income of LTCI buyers, compared with that of nonbuyers, has increased.5,21,22 Product complexity likely plays a role in deterring purchase as well.62 On the supply side, insurers have had difficulty predicting costs and setting premiums appropriately. Thus, higher-than-expected payouts (because people are living longer and not lapsing as expected) as well as greater exposure to risk owing to the potentially large size of payouts—in combination with poor investment returns due to the recession—have resulted in insurers’ increasing premiums significantly, screening applicants more closely, or dropping their LTCI business entirely—further deterring purchase.

The evident crisis in the industry has recently led some insurance company executives to reconsider their long-standing opposition to expanding public funding for LTSS. In the past, they have tended to blame Medicaid for “crowding out” private LTCI sales and supporting strict Medicaid financial eligibility standards, although there is no evidence that the progressive tightening of these rules since 1993 has increased private LTCI sales. However, the new CEO of Genworth (the largest insurer in the individual market)—who decided to stay in the market following a comprehensive review—is exploring the possibilities for private insurers and states to share premium payments and risks, with the former providing limited front-end coverage and the latter assuming the catastrophic costs.63 The CEO of LTC Partners, which offers private LTCI coverage to federal employees, retirees, and their dependents, has proposed another approach: a federally sponsored but unsubsidized voluntary LTCI plan, open to all Americans. Unlike the repealed CLASS program, the American Long-Term Care Insurance Program (ALTCIP) would be federally regulated—like the government-sponsored coverage for federal workers—but rather than insurers competing for one winner-take-all contract, multiple private LTCI companies would provide it, sharing financial risk with the federal government and private reinsurers. The policies could provide either stand-alone coverage or secondary back-end coverage coupled with a mandatory front-end social insurance program offering limited benefits.64

Thus, for US private insurers and policymakers willing to consider complementary public/private coverage for LTSS, France's experience offers both encouragement and reasons for caution. France's front-end universal public LTSS coverage has clearly encouraged the purchase of supplemental private LTCI coverage among those with sufficiently high incomes to share the cost. But the public program is in trouble because of its unanticipated high costs: in 2012, it enrolled 1.2 million people, compared with the 800,000 projected.65 These unanticipated costs are disproportionately borne by the same local governments responsible for safety-net, means-tested coverage for the poor. Thus, both countries struggle with sharing costs fairly between levels of government, and in both, local governments vary considerably in their populations and their capacity to generate tax revenues. The American system of providing more federal support for Medicaid in poorer states (by matching their Medicaid spending by as much as 83% of costs, as opposed to 50% elsewhere) only partially addresses discrepancies in their ability to finance LTSS. Access is limited in these states because state discretion regarding eligibility and benefits means that overall spending is far lower (as is the tax base), yet demand is higher due to the higher percentages of low-income residents 65 and older needing help with personal care tasks, compared with those in wealthier states. Although France has similar regional variations, the French system ensures that access to benefits is uniform but leaves the départements with a significant financing problem.

In France, the front-end public coverage offered by the APA is widely acknowledged as insufficient, even for those qualifying for full public benefits and/or with private coverage. But even though the French are less ideologically opposed than Americans are to the higher taxes needed to bolster the APA, many are worried about the French economy's ability to support them. For example, former president Sarkozy responded to widespread concerns about the APA's financial sustainability by promising reform following his 2007 inauguration, supporting a German model of social insurance, an option later dismissed as unrealistic given France's economic situation. There followed several proposals for more limited financing reform and various missed deadlines. Ultimately, recommendations were postponed until after the 2012 presidential election, which Sarkozy lost. The winner, François Hollande, promised to double the APA benefit ceiling (from €1,305 [$1,775] to €2,610 [$3,550]) during his election campaign. He took concrete steps to bolster APA finances in the 2013 budget, through a higher social security tax on elderly people's pensions. Those monies, however, have been temporarily diverted to another underfunded program for older people and were, in any case, insufficient to cover future APA costs.

Other revenue-generating ideas include sacrificing another paid annual holiday and recovering APA benefits from the estates of wealthy beneficiaries, proposals on which both left and right disagree strongly, resulting in a political stalemate. The Hollande government subsequently proposed legislation to increase APA benefits, such as lowering coinsurance requirements for those with greater needs (from 90% to 80%) as well as topping up benefit amounts: by €400 ($544) for those at GIR level 1, by €250 ($340) at level 2, €150 ($204) at level 3, and €100 ($136) at level 4. How these increases would be financed was unclear,57 though, until a June 2014 press release announced a proposal for a new dedicated tax that would generate revenues of €645 million.66 If enacted, the tax should alleviate concerns about the adequacy of APA benefits and the burdensome cost sharing required of some beneficiaries, but it would not reduce tax burdens on local government.

In France, policymakers do not expect private LTCI to save public monies or to fully protect against catastrophic out-of-pocket costs. It is seen as a complement (rather than an alternative) to a basic “floor” of universal public coverage and as a way to reduce coverage gaps for older people who need LTSS but are not poor enough to have their costs fully covered by the APA or means-tested social assistance. Political parties differ, however, in their views of government's role in the LTCI market. While the Hollande government appears less interested than Sarkozy's in working with the private LTCI industry to coordinate public (APA) and private insurance (eg, by adopting common benefit triggers), it appears more interested in improving regulatory oversight. Nonetheless, President Hollande's minister for elderly and dependent care, Michèle Delaunay, has publicly endorsed la responsabilité individuelle (individual responsibility), encouraging individuals to plan ahead by purchasing private LTCI while still working,67 an attitude toward public-private complementarity that is not at all uncommon among French socialists.68

Private LTCI, therefore, is likely to play an important and perhaps growing role in the French LTC system. In marked contrast to the US private LTCI industry, French insurers enjoy relatively healthy finances. They were less affected by the recent dips in investment returns that hit US insurers so hard. Their profits have been strong as well: for example, in 2010 LTCI insurers took in €538 ($732) million in premiums but paid out only €166 ($226) million in claims. 17 (This is not pure profit, however—they must meet reserve requirements of €3.6 billion.) In addition, the design of the French products more effectively limits financial risk to insurers. Consequently, French insurance executives appear much more optimistic about the prospects for private LTCI in France, seeing disability in an aging population as a manageable risk rather than an “epidemic of black death.”69

It is not clear, however, whether French LTCI companies envision a larger role for their products, given concerns about the adequacy of existing private LTCI benefits in France. Most people (60%) are covered through group policies that pay out an average benefit of only €150 ($204) per month. Moreover, it is currently unclear whether they will carry these policies over to their retirement years, when they are at greatest risk. Even those with more generous (and expensive) individual policies pay only €580 ($789) per month, on average, to severely disabled claimants (at GIR levels 1 and 2), an amount insufficient to meet their needs. Although French insurers are willing to sell policies that provide larger benefits (requiring higher premium payments), they have not thus far been successful in marketing them. It is not certain whether this is due to the insurers’ marketing strategies or the unwillingness of French customers to purchase higher-quality, higher-cost LTCI coverage. Currently, benefits from private LTCI pay only a tiny fraction of national LTSS costs (an estimated 0.5%) in France—far less than even the faltering US LTCI industry pays out. This may be because French LTCI claims triggers are high and benefits are low, but it may also reflect the large share of French policies covering employees who are years away from filing age-related claims and who may discontinue their coverage after retirement.

Conclusion

France has evolved a mixed public/private approach to financing LTSS for the elderly, in which private long-term care insurers have achieved a higher level of market penetration than their US counterparts have, by selling policies that complement and sometimes supplement modest universal public coverage. Interest (among both policymakers and private insurers) in pursuing explicit public/private partnerships to address high LTSS costs has waxed and waned in both nations. Currently, the interest level seems higher among insurers than among policymakers in France, although a lack of consensus and unwillingness to share information among private insurers appear to be problems.

In the United States, policymakers in some states (where much LTSS policy is made) are actively conferring with private insurers to move beyond the limited Medicaid/private LTCI partnership policies that, since 2005, are available in all but a handful of states. Because sales of such policies have somewhat offset the decline in other LTCI sales, US insurers seem to be softening their stance that they should be solely responsible for providing LTSS coverage to all but the poorest elderly, largely because they have determined that selling lifetime coverage is too risky at any price. Similarly, US supporters of public LTCI may be softening their stance as well. For example, Judith Feder, a progressive Democrat with a long history of supporting health and long-term care reform (including acting as a leader of the Clinton Health Reform Task Force and sitting on the recent Long-Term Care Commission), recently endorsed a role for private LTCI.70

Models for long-term care financing typically involve trade-offs between front-end coverage of the lower levels of support needed by the majority and the catastrophic risks assumed by the small proportion with long-term, severe disability. In France, combined APA and private LTCI coverage provides modest front-end coverage, for life. Local government provides catastrophic coverage for the poor, just as Medicaid does in the United States. One model being discussed in the United States (eg, by Feder71) is for government to assume responsibility for means-tested catastrophic coverage, giving the private sector an opportunity to offer inexpensive front-end coverage. This is not a new idea72; indeed, England recently adopted publicly funded catastrophic coverage. The difference is that the private insurance industry in the United States is becoming increasingly open to it.

Although the comparatively high market penetration of French LTCI is its strength, US insurers will be quick to note that modest benefits are its weakness. This may explain US insurers’ apparent preference for offering high dollar daily but time-limited coverage rather than modest lifetime benefits. Nevertheless, the US private LTCI industry may still benefit from some French lessons: these include marketing to a broader, less wealthy clientele by developing the simpler, cheaper cash-based products that would appeal to them. Indeed, high costs and product complexity are routinely cited as deterrents to purchase in the United States,73–76 just as they are in France.50 US insurers also could explore whether they might learn from French insurers’ greater success in marketing group coverage through employers, including both voluntary and employer-subsidized LTCI.8,76 Compared with individual policies, such policies are inexpensive because of their lower selling costs, younger mix of policyholders, and limited underwriting.

There are always reasons for skepticism about whether ideas from other countries can be successfully transferred to the United States, as their value risks being “lost in translation.” In the absence of new strategies, however, the US private LTCI market may well continue its downward spiral.

Acknowledgments

The contents of this article are the authors’ views and do not necessarily represent the views of their affiliated institutions, including the US Department of Health and Human Services and the Swiss Reinsurance Company Ltd. Several key informants provided invaluable assistance. We particularly wish to thank Etienne Dupourqué and Néfissa Sator (insurance consultants), and Emmanuelle Brun of the CNSA (French National Solidarity Fund for Autonomy).

Funding/Support

None.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. No disclosures were reported.

References

- Frank RG. Long term care financing in the United States: sources and institutions. Appl Econ Perspect Policy. 2012;34(2):333‐345. [Google Scholar]

- Tompson T, Benz J, Agiesta J, Junius D, Nguyen K, Lowell K. Long‐term care poll: perceptions, and attitudes among Americans 40 or older. SCAN Foundation website. http://www.thescanfoundation.org/sites/thescanfoundation.org/files/ap_norc_long_term_care_perception_final_report-4-24-13.pdf. Published April 2013. Accessed June 2, 2014.

- Kemper P, Komisar HL, Alexcih L. Long‐term care over an uncertain future: what can current retirees expect? Inquiry. 2006;42(4):335‐350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RW, Park JS. Who purchases long‐term care insurance? Urban Institute website. http://www.urban.org/uploadedpdf/412324-Long-Term-Care-Insurance.pdf. Published March 2011. Accessed October 2, 2013.

- Cohen M. Long‐term care insurance: a product and industry in transition. Paper presented at: NAIC Senior Issues Task Force; November 28, 2012; Fort Washington, MD: http://www.naic.org/documents/committees_b_senior_issues_2012_fall_nm_ltc_hearing_presentations_cohen_revised.pdf. Accessed July 23, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MA, Kaur R, Darnell B. Exiting the market: understanding the factors behind carriers’ decision to leave the long‐term care insurance market. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, US Department of Health and Human Services website. http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/2013/MrktExit.pdf. Published July 2013. Accessed October 31, 2013.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. A report on the actuarial, marketing, and legal analyses of the CLASS program. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, US Department of Health and Human Services website. http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/2011/class/index.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed September 13, 2013.

- Fédération française des sociétés d'assurances (FFSA). L'assurance dépendance en 2012: aspects quantitatifs et qualitatifs. Paris, France: Fédération française des sociétés d'assurances; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children's Fund. 2012. At a glance: France. UNICEF website. http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/france_statistics.htm. Accessed November 4, 2014.

- United Nations Children's Fund. 2012. At a glance: United States of America. UNICEF website. http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/usa_statistics.html. Accessed November 4, 2014.

- Choon CN, Shi'en SL, Chan A. Feminization of ageing and long term care financing in Singapore. Working Paper Series 01/2008. Singapore: National University of Singapore, Singapore Centre for Applied and Policy Economics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Comas‐Herrera A, Butterfield R, Fernández JL, Wittenberg R, Wiener JM. Barriers and opportunities for private long‐term care insurance in England: what can we learn from other countries? In: McGuire A, Costa‐Font J, eds. The LSE Companion to Health Policy. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Barr N. Long‐term care: a suitable case for social insurance. Soc Policy Adm. 2010;44(4):359‐374. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère des affaires sociale et de la santé. L'allocation personnalisée d'autonomie APA à domicile. Ministère des affaires sociale et de la santé website. http://www.social-sante.gouv.fr/informations-pratiques,89/fiches-pratiques,91/l-allocation-personnalisee-d,1900/l-allocation-personnalisee-d,12399.html. Published May 6, 2013. Accessed July 23, 2013.

- America's Health Insurance Plans. Who buys long‐term care insurance in 2010‐2011? America's Health Insurance Plans website. https://www.ahip.org/Issues/WhoBuysLTCareInsurance2010-2011%20.pdf. Published 2012. Accessed August 7, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine R, Zerrar N. How to explain why so few individuals insure themselves against the risk of old‐age dependency? Paris, France: Institut de recherche et documentation en économie de la santé; 2013;188:1‐7. [Google Scholar]

- Fédération française des sociétés d'assurances (FFSA). Les contrats d'assurance dependance en 2010. Fédération française des sociétés d'assurances website. http://www.ffsa.fr/sites/jcms/p1_415837/fr/les-contrats-dassurance-dependance-en-2010?cc=fn_7350. Published April 21, 2011. Accessed May 2, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Plisson M. Why do the French not purchase more long‐term care cover? SCOR Global Risk Center website. http://www.scor.com/images/stories/pdf/scorpapers/sp15_en.pdf. Published May 2011. Accessed August 13, 2013.

- Les Echos. Dépendance: les assurés ont principalement des revenus modestes. Les Echos. 2012;21228:22 http://www.lesechos.fr/17/07/2012/LesEchos/21228-127-ECH_dependance-les-assures-ont-principalement-des-revenus-modestes.htm?texte=BERTRAND%20LAUZERAL. Accessed August 5, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Courbage C, Roudault N. Empirical evidence on LTC insurance purchase in France. Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance. 2008;33(4):645‐658. [Google Scholar]

- Ujvari K. Long term care insurance: 2012 update. AARP Public Policy Institute website. http://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/research/public_policy_institute/ltc/2012/ltc-insurance-2012-update-AARP-ppi-ltc.pdf. Published June 2012. Accessed August 5, 2013.

- Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE). Background briefing: long‐term care insurance. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Department of Health and Human Services website. http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/reports/2012/ltcinsRB.shtml. Published June 2012. Accessed August 12, 2013.

- Brown JR, Finkelstein A. The private market for long‐term care insurance in the United States: a review of the evidence. J Risk Insur. 2009;76(1):5‐29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer AT, Jensen GA. Why don't people buy long‐term care insurance? J Gerontol: Soc Sci. 2006;61B:S185‐S193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bihan B, Martin C. Reforming long‐term care policy in France: private‐public complementarities. Soc Policy Adm. 2010;44(4):392‐410. [Google Scholar]

- Fragonard B. Stratégie pour la gouvernance de la dépendance des personnes âgées—rapport du groupe n° 4 sur la prise en charge de la dépendance. Ministère des solidarités et de la cohésion sociale website. http://www.social-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/rapport_du_groupe_n_4_vdefinitive.pdf. Published June 2011. Accessed July 30, 2013.

- Dufour‐Kippelen S. L'assurance dépendance privée en France: spécificité du risque dépendance, caractéristiques des contrats, acteurs, prospective. Paper presented at: Colloque protection sociale d'entreprise; 2010; Paris, France.

- Lautie S, Loones A, Rose N. Le financement de la perte d'autonomie liée au vieillissement: regards croisés des acteurs du secteur. Centre de recherche pour l’étude et l'observation des conditions de vie website. http://www.credoc.fr/pdf/Rech/C286.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed July 30, 2013.

- Direction de la recherche, des études, de l’évaluation et des statistiques (DREES). Les retraités et les retraites en 2010. DREES website. http://www.drees.sante.gouv.fr/les-retraites-et-les-retraites-en,10852.html. Published March 12, 2012. Accessed July 30, 2013.

- Broussy L. L'adaptation de la société au vieillissement de sa population: France: année zero! Mission interministérielle sur l'adaptation de la société française au vieillissement de sa population website. http://www.ladocumentationfrancaise.fr/var/storage/rapports-publics/134000173/0000.pdf. Published January 2013. Accessed July 30, 2013.

- Dufour‐Kippelen S. Les contrats d'assurance dépendance sur le marché français en 2006. Working Paper: Études et recherches n° 84. Paris, France: Direction de la recherche, des études, de l’évaluation et des statistiques; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fédération française des sociétés d'assurances (FFSA). Les contrats d'assurance dépendance en 2009. Fédération française des sociétés d'assurances website. http://www.ffsa.fr/sites/jcms/p1_80891/fr/les-contrats-dassurance-dependance-en-2009?cc=fn_7350. Published April 23, 2010. Accessed May 2, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Mutualite française. Le dépendence: un sujet de préoccupation pour les français qui attendent beaucoup des mutuelles. Mutualité française website. http://www.mutualite.fr/L-actualite/Kiosque/Communiques-de-presse/La-dependance-un-sujet-de-preoccupation-pour-les-Francais-qui-attendent-beaucoup-des-mutuelles. Published May 24, 2011. Accessed July 30, 2013.

- Mature Market Institute. MetLife long‐term care IQ: removing myths, reinforcing realities. MetLife website. https://www.metlife.com/mmi/research/long-term-care-iq.html#findings. Published September 2009. Accessed April 15, 2012.

- Hémon D, Jougla E. The heat wave in France in August 2003. Rev Epidemiol Santé Publique. 2004;52:3‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandentorren S, Bretin P, Zeghnoun A, et al. August 2003 heat wave in France: risk factors for death of elderly people living at home. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16(6):583‐591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koven S, Michel S. Womanly duties: maternalist politics and the origins of welfare states in France, Germany, Great Britain, and the United States, 1880‐1920. Am Hist Rev. 1990;95(4):1076‐1108. [Google Scholar]

- Esping‐Andersen G. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Costa‐Font J. Family ties and the crowding out of long‐term care insurance. Oxford Rev Econ Policy. 2010;26(4):691‐712. [Google Scholar]

- Costa‐Font J. Reforming Long‐Term Care in Europe. London, UK: Wiley‐Blackwell; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jönsson I, Daune‐Richard A, Odena S, Ring M. The implementation of elder‐care in France and Sweden: a macro and micro perspective. Ageing Soc. 2011;31(4):625‐644. [Google Scholar]

- Haberkern K, Szydlik M. State care provision, societal opinion and children's care of older parents in 11 European countries. Ageing Soc. 2010;30(2):299‐323. [Google Scholar]

- Morel N. Providing coverage against new social risks in Bismarckian welfare states: the case of long‐term care. In: Armingeon K, Bonoli G, eds. The Politics of Postindustrial Welfare States: Adapting Social Policies to New Social Risks. London, UK: Routledge; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Morel N. From subsidiary to “free choice”: child and elder care policy reforms in France, Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands. Soc Policy Adm. 2007;41(6):618‐637. [Google Scholar]

- Trading Economics. The French unemployment rate. Trading Economics website. http://www.tradingeconomics.com/france/unemployment-rate. Published December 5, 2013. Accessed March 14, 2014.

- Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD). OECD annual projections: NAIRU—unemployment rate with non‐accelerating inflation rate. OECD website. http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?QueryId=36376. Published June 2012. Accessed July 23, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aldeghi I, Loones A. Les emplois dans les services à domicile aux personnes âgées. Centre de recherche pour l’étude et l'observation des conditions de vie website. http://www.credoc.fr/pdf/Rech/C277.pdf. Published December 2010. Accessed August 5, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard C, Hallal S, Nicolaï JP. La Silver Économie, une opportunité de croissance pour la France. Commissariat général à la stratégie et à la prospective website. http://www.strategie.gouv.fr/blog/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/CGSP_Silver_Economie_dec2013_03122013.pdf. Published December 2013. Accessed February 16, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chevreul K, Berg Brigham K. Financing long‐term care for frail elderly in France: the ghost reform. Health Policy. 2013;111(3):213‐220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautie S, Loones A, Rose N. Le financement de la perte d'autonomie liée au vieillissement: regards croisés des acteurs du secteur. Centre de recherche pour l’étude et l'observation des conditions de vie website. http://www.credoc.fr/pdf/Rech/C286.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed July 30, 2013.

- Nahmias L. The financial crisis and household savings behaviour in France. BNP Paribas, Conjoncture website. http://economic-research.bnpparibas.com/Views/DisplayPublication.aspx?type=document&IdPdf=10588. Published October 2010. Accessed November 7, 2013.

- Pincus J, Wallace‐Hodel K, Brown K. The size of the employer and self‐employed markets without access to long‐term care coverage options. SCAN Foundation website. http://thescanfoundation.org/sites/thescanfoundation.org/files/tsf_ltc-financing_size-employer-market_pincus_3-20-13_0.pdf. Published March 2013. Accessed October 3, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Menioux J. Risk management as business enabler. Geneva Association Working Papers Series. Études et dossiers no. 353. http://genevaassociation.org/PDF/Working_paper_series/GA_E&D_353.05_MENIOUX_Risk_management,Long-term_care,Demographics.pdf. Published November 20, 2008. Accessed May 2, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Malleray P. L'Assurance Dépendance: Comparaisons Internationales et Leçons. Paris, France: L'Ecole nationale d'assurances; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Botti S, Iyengar SS. The dark side of choice: when choice impairs social welfare. J Public Policy Market. 2006;25(1):24‐38. [Google Scholar]

- Liebman J, Zeckhauser R. Simple humans, complex insurance, subtle subsidies. Working Paper no. 14330. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research; 2008. http://www.nber.org/papers/w14330.pdf?new_window=1. Accessed August 7, 2013.

- Ministère des affaires sociale et de la santé. Projet de rapport annexé à la loi d'orientation et de programmation pour l'adaptation de la société au vieillissement. Ministère des affaires sociale et de la santé website. http://ancreai.org/sites/ancreai.org/files/rapport_annexe_loi_autonomie_pour_le_ce.pdf. Published February 14, 2014. Accessed March 10, 2014.

- Rodwin VG. The health care system under French national health insurance: lessons for health reform in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(1):31‐37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe S. Long‐term care panel releases recommendations but fails to offer plan to help pay for services. Kaiser Health News website. http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/Stories/2013/September/13/long-term-care-commission-recommendations.aspx. Published September 13, 2013. Accessed November 15, 2013.

- Warshawsky M. Millionaires on Medicaid. Wall Street Journal. January 6, 2014. http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB1000142405270230432500457929705295041698. Accessed January 24, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Doty P, Cohen MA, Miller J, Shi X. Private long‐term care insurance: value to claimants and implications for long‐term care financing. Gerontologist. 2010;50(5):613‐622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns B. Comparing long‐term care insurance policies: bewildering choices for consumers. Washington, DC: Public Policy Institute, AARP; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gleckman H. Genworth CEO would support public/private long‐term care insurance. Forbes. December 11, 2013. http://www.forbes.com/sites/howardgleckman/2013/12/11/genworth-ceo-would-support-publicprivate-long-term-care-insurance/2/. Accessed January 24, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Forte PE. Fresh thinking on long‐term care financing: the American long‐term care insurance program. Contingencies. 2014;48‐55. http://www.contingenciesonline.com/contingenciesonline/20140102#pg1. Accessed January 24, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nadash P, Doty P, Mahoney K, Von Schwanenflugel M. European long‐term care programs: lessons for Community Living Assistance Services and Supports? Health Serv Res. 2012;47(1):309‐328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ministère des affaires sociale et de la santé. Dossier de presse 3 juin 2014: projet de loi relatif à l'adaptation de la société au vieillissement. http://www.social-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/03_06_14_-_DP_-_Projet_de_loi_autonomie.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2014.

- Guichard G. Dependency: toward low‐cost reforms. Le Figaro website. http://www.lefigaro.fr/conjoncture/2013/03/10/20002-20130310ARTFIG00157-dependance-vers-une-reforme-a-bas-cout.php. Published November 3, 2013. Accessed July 30, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton PV. Differential Diagnoses: A Comparative History of Health Care Problems and Solutions in the United States and France. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Les Recontres du CORA. Regards croisés franco‐allemands sur la dépendance. http://webcast.viewontv.com/webcast_ffsa_21042011.html. Published April 21, 2011. Accessed April 21, 2011.

- Mullaney T. Senators weigh need for individual mandate in long‐term care financing reform. McKnight's. http://www.mcknights.com/senators-weigh-need-for-individual-mandate-in-long-term-care-financing-reform/article/326303/. Published December 19, 2013. Accessed November 19, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gleckman H. It is time to think about catastrophic long‐term care insurance. Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/sites/howardgleckman/2013/10/25/it-is-time-to-think-about-catastrophic-long-term-care-insurance/. Published October 25, 2013. Accessed November 19, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop CE. A federal catastrophic long‐term care insurance program. Working Paper no. 5. Georgetown University Long‐Term Care Financing Project. http://hpi.georgetown.edu/ltc/papers.html. Published June 2007. Accessed November 19, 2014.

- Brown J, Goda GS, McGarry K. Long‐term care insurance demand limited by beliefs about needs, concerns about insurers, and care available from family. Health Aff. 2012;31(6):1294‐1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry LA, Robison J, Shugrue N, Keenan P, Kapp M. Individual decision making in the non‐purchase of long‐term care insurance. Gerontologist. 2009;49(4):560‐569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank RG, Cohen M, Mahoney N. Making progress: expanding risk protection for long‐term services and supports through private long‐term care insurance. SCAN Foundation website. http://www.thescanfoundation.org/sites/thescanfoundation.org/files/tsf_ltc-financing_private-options_frank_3-20-13.pdf. Published March 2013. Accessed June 7, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Coronel S. The private long‐term care insurance market in the United States. Health Ageing. 2011;24:1‐6. [Google Scholar]