Abstract

The performance of two DNA line probe assays, a new version of INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria (Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium) and the GenoType Mycobacterium (Hain Diagnostika, Nehren, Germany), were evaluated for identification of mycobacterial species isolated from liquid cultures. Both tests are based on a PCR technique and designed for simultaneous identification of different mycobacterial species by reverse hybridization and line probe technology. The INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria v2 targeting the 16S-23S rRNA gene spacer region was developed for the simultaneous identification of 16 different mycobacterial species. The GenoType Mycobacterium, which targets the 23S rRNA gene, allows simultaneous identification of 13 mycobacterial species. Both tests were evaluated on 110 mycobacterial strains belonging to 22 different mycobacterial species (20 reference strains, 83 clinical strains, and 4 Mycobacterium kansasii strains isolated from tap water) that were previously inoculated into MB/BacT bottles. The sensitivity of both methods, defined as the number of positive results obtained with the Mycobacterium genus probe together with an interpretable result on the number of samples tested was 110 of 110 (100%) for INNO-LiPA and 102 of 110 (92.7%) for GenoType. For samples with interpretable results, INNO-LiPA was able to correctly identify 109 of 110 samples (99.1%), whereas the GenoType correctly identified 100 of 102 samples (98.0%). Both tests were easy to perform, rapid, and reliable when applied to mycobacterial identification directly from MB/BacT bottles.

Since the introduction of liquid culture methods, the time required for both the detection and identification of mycobacteria has been significantly shortened (1). In comparison with solid media, liquid culture methods not only detect mycobacterial growth more rapidly but also increase overall mycobacterial recovery. The application of new molecular techniques directly on positive liquid and solid cultures for the identification of mycobacterial isolates has led to faster and more accurate diagnosis of tuberculosis (3, 7, 8, 10-12, 18, 21-23).

In recent years, several technical strategies and designs in molecular biology tests for the identification of mycobacteria have been developed. Some of them are currently commercially available, such as sequencing systems (4), liquid medium hybridization techniques (3, 16), and in situ hybridization techniques (12, 19).

Recently, new molecular biology techniques based on the PCR and reverse hybridization procedure have been marketed for mycobacterial identification (7, 8, 10, 11, 18, 21-23). The hybridization technique is performed on nitrocellulose strips onto which probe lines are fixed in parallel. This format enables simultaneous detection and identification of different mycobacterial species. At present, two systems with this design are commercially available in Europe, the INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria test, designed to amplify the mycobacterial 16S-23S rRNA spacer region (8, 10, 11, 18, 21-23), and the GenoType Mycobacteria assay, targeting the mycobacterial 23S rRNA (7). Any of these methods are available in the United States as Food and Drug Administration-approved tests and are used only for diagnosis.

The first version of the INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria system enabled simultaneous identification of eight different mycobacterial species: Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, Mycobacterium kansasii, Mycobacterium xenopi, Mycobacterium gordonae, Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, Mycobacterium scrofulaceum, and Mycobacterium chelonae complex. This version of the test has been extensively evaluated with success for identification of mycobacteria isolated from solid and liquid cultures (8, 10, 11, 18, 21-23).

Recently, this test has evolved towards a second version, INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria v2, which increased the identification capacity to 16 different mycobacterial species. Besides the species detected in the first version, the second version includes specific probes for Mycobacterium genavense, Mycobacterium simiae, Mycobacterium marinum/Mycobacterium ulcerans, Mycobacterium malmoense, Mycobacterium haemophilum, Mycobacterium fortuitum complex, and Mycobacterium smegmatis. Moreover, the new version includes a new probe for M. intracellulare. This new version has recently been evaluated by Tortoli et al. (24).

The GenoType Mycobacteria assay allows simultaneous identification of 13 different mycobacterial species: M. tuberculosis complex, M. kansasii, M. xenopi, M. gordonae, M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. scrofulaceum, M. chelonae, M. malmoense, M. fortuitum, Mycobacterium celatum, Mycobacterium peregrinum, and Mycobacterium phlei. The performance of this test has also been assessed in several studies (7).

The purpose of this study was to perform a comparative study to assess the ability of both tests, INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria v2 (Innogenetics, Ghent, Belgium) and GenoType Mycobacteria (Hain Diagnostika, Nehren, Germany), for mycobacterial identification when applied directly to positive MB/Bact liquid cultures (BioMérieux, Marcy l'Etoile, France) containing mycobacterial isolates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mycobacterial strains.

A total of 110 mycobacterial strains belonging to 22 different species (20 reference strains, 83 clinical strains, and 4 M. kansasii strains isolated from tap water) were included in this study. To determine the ability of the test to detect mixed mycobacterial cultures, three samples containing two different mycobacterial strains were also included in the study (one M. avium plus M. fortuitum, one M. xenopi plus one M. tuberculosis, and one M. kansasii plus one M. avium). Reference strains comprising three M. intracellulare (ATCC 13950), one M. smegmatis (ATCC 35797), one M. smegmatis (ATCC 14468), two M. simiae (ATCC 25275), one Mycobacterium terrae (ATCC 15755), one Mycobacterium gastri (IP 140340003), one Mycobacterium vaccae (ATCC 15483), two M. fortuitum (ATCC 6841), one M. peregrinum (ATCC 144675), one Mycobacterium mucogenicum (ATCC 496503), one Mycobacterium triviale (CIPT 140330003), one M. avium (ATCC 25291), one M. gordonae (ATCC 14470), one M. tuberculosis (H37Ra), one M. tuberculosis (ATCC 27294), and one M. xenopi (NCTC 10042).

Eighty-three mycobacterial clinical strains isolated from human clinical specimens previously identified in our laboratory were also included in this study: 27 M. tuberculosis, 1 Mycobacterium bovis, 1 Mycobacterium africanum, 10 M. avium, 2 Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC), 2 M. intracellulare, 1 M. scrofulaceum, 10 M. kansasii, 6 M. gordonae, 5 M. fortuitum, 2 M. peregrinum, 2 M. chelonae, 1 Mycobacterium abscessus, 6 M. xenopi, 1 Mycobacterium thermoresistibile, 1 M. simiae, 1 M. mucogenicum, 1 Mycobacterium flavescens, 2 M. terrae, and 1 Mycobacterium szulgai.

All mycobacterial strains were inoculated into MB/BacT bottles (BioMérieux) as follow. Once isolated on Löwenstein-Jensen slants, a few representative colonies of each strain were used to perform a mycobacterial suspension with an optical density equivalent to a McFarland no. 1 standard. Tenfold dilutions to obtain approximately 105 cells/ml were performed in 5-ml sterile glass test tubes. Finally, 100 μl of each suspension was inoculated into MB/BacT bottles. When an MB/BacT culture was positive, an aliquot of medium was obtained for acid-fast staining. Upon confirmation of isolates as acid fast, an aliquot was subcultured onto two Löwenstein-Jensen slants and two other 500-μl aliquots were used to perform the INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria v2 and GenoType Mycobacteria assays.

Microscopy.

Investigation of acid-fast bacilli from positive liquid cultures was performed with an auramine-rhodamine stain. Positive slides were confirmed by the Ziehl-Neelsen technique.

Identification of mycobacteria.

Conventional biochemical methods (15), gas-liquid chromatography, thin-layer chromatography (6), and the AccuProbe (BioMérieux) system (3, 16) were used for mycobacterial clinical strain identification.

Discrepant results.

Discrepant identification results were resolved by sequence analysis of the mycobacterial 16S-23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region. Sequence analysis was determined on both strands by direct sequencing of the PCR product on an automated model 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) with fluorescence-labeled dideoxynucleotide terminators (ABI Prism Big Dye terminator cycle sequencing ready reaction kit; Applied Biosystems). Amplicons were purified with a PCR purification kit (Qiagen Ltd., Crawley, West Sussex, England). The sequence reactions were performed with the two PCR primers separately. The new ITS sequences were aligned with those available in the database (GenBank and National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI]) and further processed with Kodon version 2.0 (Applied Maths, Sint-Martens Latem, Belgium) (9).

INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria and GenoType Mycobacterium protocol.

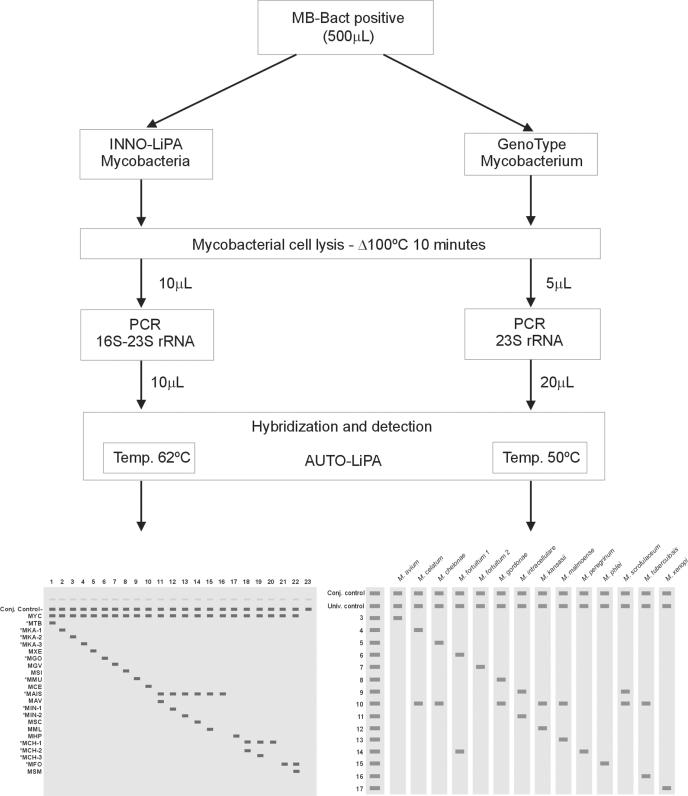

Both the INNO-LiPA Myocobacteria and GenoType Mycobacterium assays consist of three steps: a mycobacterial cell lysis method for releasing nucleic acids, a PCR-based technique, and a reverse hybridization technique designed for simultaneous detection of different mycobacterial species. Figure 1 shows a schematic representation of both procedures.

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria v2 and GenoType Mycobacterium procedures. For INNO-LiPA, line 1, Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex; line 2, Mycobacterium kansasii group I; line 3, M. kansasii group II; line 4, M. kansasii groups III, IV, and V and Mycobacterium gastri; line 5, Mycobacterium xenopi; line 6, Mycobacterium gordonae; line 7, Mycobacterium genavense; line 8, Mycobacterium simiae; line 9, Mycobacterium marinum plus Mycobacterium ulcerans; line 10, Mycobacterium celatum; line 11, Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium paratuberculosis, and Mycobacterium silvaticum; line 12, Mycobacterium intracellulare (sequevars Min-A, -B, -C, and -D); line 13, M. intracellulare sequevar Mac-A; line 14, Mycobacterium scrofulaceum; line 15, Mycobacterium malmoense; line 16, M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. scrofulaceum, MAC, and M. malmoense; line 17, Mycobacterium haemophilum; line 18, Mycobacterium chelonae complex (group III; Mycobacterium abscessus); line 19, M. chelonae (group I); line 20, M. chelonae complex (groups I, II, III, and IV and M. abscessus); line 21, Mycobacterium fortuitum-Mycobacterium peregrinum complex; line 22, Mycobacterium smegmatis; and line 23, no Mycobacterium organisms. Conjugated (Conj.) and universal (Univ.) controls are shown.

Mycobacterial cell lysis procedure.

For this study we used a simple mycobacterial lysis method previously described by Padilla et al. (13). Briefly, a 500-μl aliquot from each MB/BacT positive culture was transferred to a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was poured off. The sediment obtained was resuspended in 100 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]). The resuspended pellet was subsequently heated at 100°C for 10 min and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 10 s. Ten microliters of supernatant containing the extracted mycobacterial nucleic acids was used to perform the subsequent amplification step of both the INNO-LiPA and GenoType assays.

PCR. (i) INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria v2.

A PCR-based amplification of the 16S-23S rRNA spacer region of the Mycobacterium species was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 10 μl of the extracted mycobacterial DNA was transferred into a 0.2-ml amplification tube containing 40 μl of an amplification mixture including 19.7 μl of autoclaved distilled water, 10 μl of amplification buffer containing all deoxyribonucleoside 5′-triphosphates, 10 μl of MYC primer solution containing biotinylated primers and MgCl2, and 0.3 μl of thermostable DNA polymerase (Taq DNA polymerase, 5 U/μl; Promega, Madison, Wis.). All reagents except thermostable DNA polymerase were supplied by the manufacturer.

The PCR was performed in an automated thermocycler (GenAmp PCR System 2700; Applied Biosystems) with the following amplification profile: initial denaturation at 95°C for 1 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 62°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s.

(ii) GenoType Mycobacteria assay.

An amplification mixture of 50.2 μl was prepared. This reaction mix contained 35 μl of PN mix, including biotinylated primers and deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 5 μl of 10× polymerase buffer (Qiagen) containing 15 mM MgCl2 and 2 μl of 25 mM MgCl2 solution (Qiagen) for a final concentration of 1.5 mM per 50 μl of PCR mixture, 0.2 μl of HotStart Taq DNA polymerase at 5 U/μl (Qiagen), and 3 μl of autoclaved distilled water. Subsequently, 5 μl of the processed specimen containing the extracted mycobacterial DNA was added. The amplification reaction was carried out in a thermal cycler (GenAmp PCR System 2700) and run for 1 cycle at 95°C for 15 min, 10 cycles of 95°C for 30 s and 58°C for 2 min, 20 cycles of 95°C for 25 s, 53°C for 40 s, and 70°C for 40 s, and one cycle of 70°C for 8 min.

Amplification quality control.

For all clinical strains tested, the presence of amplified product was also verified on ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gels. For the LiPA test, the amplified target should appear as a single band corresponding to a length of 400 to 550 bp. For the GenoType Mycobacterium assay, the amplicon should appear as a single band with a length of approximately 200 bp.

Hybridization and detection of amplified product. (i) INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria v2.

Once PCR was achieved, the biotinylated amplicon was subsequently hybridized with a typing strip onto which 22 parallel DNA probes and two control lines are fixed. The design of the LiPA strip allows simultaneous identification of 16 different mycobacterial species (Fig. 1).

The hybridization and detection of amplified product were performed in an automated instrument (Auto-LiPA). The hybridization step is based on the reverse hybridization principle with specific oligonucleotide probes immobilized as parallel lines on membrane-based strips. After hybridization, streptavidin labeled with alkaline phosphatase is added and bound to the biotinylated hybrid formed. Previous to the hybridization step, a 10-μl aliquot of the amplified product was denatured with denaturation solution in a hybridization trough containing the LiPA strip. The remainder of the procedure was carried out automatically in the Auto-LiPA instrument. The whole procedure, which includes a hybridization step at 62°C for 30 min and a detection step, was performed in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol.

Following denaturation of amplification product, 2 ml of warm (62°C) hybridization solution was added to the hybridization trough containing the LiPA strip and incubated for 30 min at 62°C on a shaking platform. The strip was washed twice for 3 min with 2 ml of stringent wash solution, followed by a further incubation at 62°C for 4 min. The remainder of the procedure was done at room temperature. The strip was washed twice with rinse solution, and 2 ml of conjugate (streptavidin labeled with alkaline phosphatase) was added for 30 min. After incubation, the strip was washed twice with 2 ml of rinse solution and once with 2 ml of substrate buffer prior to incubation with substrate solution (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoylphosphate and nitroblue tetrazolium) for 30 min with shaking. Last, the strip was washed twice with 2 ml of distilled water. The presence of clearly visible purple-brown bands on the LiPA strip was considered a positive hybridization reaction. Each hybridization strip includes a positive control line representing a Mycobacterium genus hybridization probe (MYC control). This line is used to check for the presence of amplified product after hybridization, and it must always be positive when a Mycobacterium species is present. Moreover, the LiPA strip includes a line representing the conjugate control line, which must always be visible.

(ii) GenoType Mycobacterium test.

The hybridization of biotin-labeled amplicons is performed on a nitrocelullose strip onto which 15 parallel DNA probes and two control lines are fixed, allowing identification of 13 different mycobacterial species. The hybridization and detection of amplified product were also performed with the automated Auto-LiPA instrument following a process similar to that described above. Before the hybridization procedure was performed, a 20-μl aliquot of the amplified product was denatured with denaturation solution in a hybridization trough containing the strip. All steps of the hybridization and detection procedures were done automatically in the Auto-LiPA instrument and performed in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol.

Following denaturation of amplification product, 1 ml of warm (50°C) hybridization solution was added to the hybridization trough containing the GenoType strip and incubated for 30 min at 50°C with shaking. The strip was washed once for 2 min with 1 ml of stringent wash solution, followed by further incubation at 50°C for 15 min. The remainder of the procedure was done at room temperature. The strip was subsequently washed twice for 2 min with 1 ml of rinse I solution, and 1 ml of conjugate (streptavidin labeled with alkaline phosphatase) was added for 30 min. After incubation, the strip was washed twice with 1 ml of rinse II solution for 2 min and once with 1 ml of distilled water prior to incubation with substrate solution (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoylphosphate and nitroblue tetrazolium) for 10 to 15 min with shaking. Last, the strip was washed twice with 1 ml of distilled water.

Each hybridization strip includes a universal control designed to hybridize with all known mycobacteria and members of the group of gram-positive bacteria with a high G+C content. This line is used to check for the presence of amplified product after hybridization, and it must always be positive. Moreover, the strip includes a line representing the conjugate control line to verify the efficiency of conjugate binding and substrate reaction. This band must always be visible. Only those bands whose intensities were about as strong as or stronger than that of the universal control line were considered positive. Taking into account this last consideration, hybridization patterns different from those shown in the GenoType Mycobacterium package insert (Fig. 1) should be considered noninterpretable hybridization results.

Safety procedures.

In this study, all procedures were done with the safety procedures recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (17).

RESULTS

INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria v2.0 assay.

The INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria v2.0 correctly identified 109 of the 110 isolates tested (99%) compared with laboratory identification methods (Table 1). A discrepant identification result was obtained for one M. thermoresistibile isolate that was identified as M. fortuitum-M. peregrinum complex by the LiPA assay. This isolate was identified as M. thermoresistibile by sequencing analysis of the mycobacterial 16S-23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer region.

TABLE 1.

Identification of mycobacteria from MB/BacT liquid cultures containing one mycobacterial isolate by the INNO LiPA and GenoType assays

| Mycobacterium species | No. of strains | INNO-LiPA results

|

GenoType results

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Band patterns | Identificationa | Band patterns | Identification | ||

| M. tuberculosis | 29 | 1, 2, 3 | MTBC | 1, 2, 10, 16 | MTBC |

| M. bovis | 1 | 1, 2, 3 | MTBC | 1, 2, 10, 16 | MTBC |

| M. africanum | 1 | 1, 2, 3 | MTBC | 1, 2, 10, 16 | MTBC |

| M. avium | 11 | 1, 2, 13, 14 | M. avium | 1, 2, 3, 11 | M. avium |

| M. avium complex | 2 | 1, 2, 13 | MAIS | 1, 2, 10 | UP |

| M. avium complex | 1 | 1, 2, 13, 16 | M. intracellulare (Mac-A) | 1, 2, 10 | UP |

| M. intracellulare | 4 | 1, 2, 13, 15 | M. intracellulare | 1, 2, 9, 11 | M. intracellulare |

| M. scrofulaceum | 1 | 1, 2, 13, 17 | M. scrofulaceum | 1, 2, 9, 10 | M. scrofulaceum |

| M. kansasii | 8 | 1, 2, 4 | M. kansasii I | 1, 2, 10, 12 | M. kansasii |

| M. kansasii | 2 | 1, 2, 5 | M. kansasii II | 1, 2, 10, 12 | M. kansasii |

| M. kansasii | 4 | 1, 2, 6 | M. kansasii III, V, IV (M. gastri) | 1, 2, 10, 12 | M. kansasii |

| M. gastri | 1 | 1, 2, 6 | M. kansasii III, V, IV (M. gastri) | 1, 2, 10 | UP |

| M. gordonae | 7 | 1, 2, 8 | M. gordonae | 1, 2, 8, 10 | M. gordonae |

| M. fortuitum | 7 | 1, 2, 23 | M. fortuitum-M. peregrinum complex | 1, 2, 6, 14 | M. fortuitum I |

| M. peregrinum | 3 | 1, 2, 23 | M. fortuitum-M. peregrinum complex | 1, 2, 14 | M. peregrinum |

| M. smegmatis | 1 | 1, 2, 23, 24 | M. smegmatis | 1, 2, 7 | M. fortuitum II |

| M. chelonae | 2 | 1, 2, 20 | M. chelonae complex (I, II, III, IV, M. abscessus) | 1, 2, 5, 10 | M. chelonae complex |

| M. abscessus | 1 | 1, 2, 20, 21 | M. chelonae complex (III, M. abscessus) | 1, 2, 5, 10 | M. chelonae complex |

| M. xenopi | 7 | 1, 2, 7 | M. xenopi | 1, 2, 17 | M. xenopi |

| M. thermoresistibile | 1 | 1, 2, 23 | M. fortuitum-M. peregrinum complex | 1, 2, 4, 10 | M. celatum |

| M. simiae | 3 | 1, 2, 10 | M. simiae | 1, 2 | NTM |

| M. vaccae | 1 | 1, 2 | NTM | 1, 2 | NTM |

| M. mucogenicum | 2 | 1, 2 | NTM | 1, 2 | NTM |

| M. triviale | 1 | 1, 2 | NTM | 1, 2 | NTM |

| M. flavescens | 1 | 1, 2 | NTM | 1, 2 | NTM |

| M. terrae | 1 | 1, 2 | NTM | 1, 2, 10, 16b | UP |

| M. terrae | 2 | 1, 2 | NTM | 1, 2, 10 | UP |

| M. smegmatis | 1 | 1, 2, 23, 24 | M. smegmatis | 1, 2 | NTM |

| M. szulgai | 1 | 1, 2 | NTM | 1, 2, 10 | UP |

MAC, M. avium-M. intracellulare complex; NTM, nontuberculous mycobacteria; UP, noninterpretable pattern; MTBC, M. tuberculosis complex; MAIS, M. avium-M. intracellulare-M. scrofulaceum.

Band 16 showed a weakly positive hybridization signal.

Two isolates identified in our laboratory as M. avium-M. intracellulare-M. scrofulaceum (MAIS) complex produced a MAIS pattern on the INNO-LiPA strip (positive hybridization results with the MAIS probe but negative for specific M. avium, M. intracellulare, and M. scrofulaceum probes). These two strains, when tested with AccuProbe, hybridized with MAC probes, but we obtained a negative hybridization signal with probes specific for M. avium and M. intracellulare. The ITS sequences for these two strains were different and showed 100% homology with the Mac-U sequevar and 99% homology with the Mac-Q sequevar. One isolate identified by AccuProbe as M. intracellulare was identified as M. intracellulare sequevar Mac-A by the INNO-LiPA test.

Eight of the 14 M. kansasii isolates were identified by the INNO-LiPA assay as M. kansasii group I. Positive hybridization results were obtained for 4 M. kansasii isolates with the MKA-3 probe, which specifically reacts with M. kansasii groups III, IV, and V and M. gastri. These four isolates corresponded with the strains isolated from tap water. The last two M. kansasii strains were identified as M. kansasii group II.

One M. abscessus isolate hybridized with the MCH-2 probe, which comprises M. chelonae complex group III and M. abscessus.

Nine NTM isolates, M. vaccae (n = 1), M. mucogenicum (n = 2), M. triviale (n = 1), M. terrae (n = 3), M. flavescens (n = 1), and M. szulgai (n = 1), were identified by the INNO-LiPA assay as Mycobacterium spp.

GenoType Mycobacterium assay.

In comparison with laboratory identification methods, the GenoType assay provided correct mycobacterial identification for 100 (91.0%) of the 110 mycobacterial isolates tested (Table 1). We obtained eight noninterpretable hybridization patterns for 2 MAIS, 1 M. intracellulare, 1 M. gastri, 3 M. terrae, and 1 M. szulgai strain (Table 1). Because the GenoType hybridization strip includes specific probes for M. avium, M. intracellulare, and M. scrofulaceum, the noninterpretable hybridization patterns obtained for the two MAIS and one M. intracellulare isolate were considered incorrect identification results. Moreover, one M. thermoresistibile isolate was misidentified as M. celatum, and one M. smegmatis isolate was identified as M. fortuitum II. These two mycobacterial strains were identified as M. thermoresistibile and M. smegmatis, respectively, when they were analyzed by sequencing of the mycobacterial 16S-23S rRNA gene internal transcribed spacer region.

There were three isolates of M. simiae, one of M. vaccae, two of M. mucogenicum, one of M. triviale, one of M. flavescens, and one of M. smegmatis that were identified to only the Mycobacterium genus level by the GenoType assay.

In comparison with laboratory identification, there was complete agreement between the INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria v2.0 and GenoType Mycobacterium assays for 100 (91.0%) of the 110 mycobacterial isolates tested.

The INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria v2.0 assay correctly identified 100% (100 of 100) of the mycobacterial isolates within the identification range of the test, while the GenoType assay correctly identified 96.8% (91 of 94).

The sensitivity of both methods, defined as the number of positive results obtained with the Mycobacterium genus probe together with interpretable results on the number of isolates tested, was 110 of 110 (100%) for the INNO-LiPA assay and 102 of 110 (92.7%) for GenoType. For samples with interpretable results, the INNO-LiPA correctly identified 109 of 110 (99.1%), whereas GenoType was able to correctly identify 100 of 102 (98.0%)

DISCUSSION

In this study, we compared the new version of the INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria and GenoType Mycobacterium assays for identification of Mycobacterium species from acid-fast bacilli-positive MB/BacT bottles. At present, this is the first study in which both molecular identification methods were evaluated.

In previous reports, the first version of INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria was evaluated with success (8, 10, 11, 18, 21-23). The first version of the assay enabled simultaneous identification of eight different mycobacterial species. In the new version, the LiPA strip provides probes for identification of 16 different mycobacterial species. In comparison with the previous format, the new version of the LiPA strip has additional probes for M. genavense, M. simiae, M. marinum plus M. ulcerans, M celatum, M. malmoense, M. haemophilum, M. fortuitum-M. peregrinum complex, and M. smegmatis. Moreover, a new probe has been added to the new LiPA strip, the MIN-2 probe, designed to specifically hybridize with M. intracellulare sequevar Mac-A. The new format of the strip allows identification to the species level of M. intracellulare sequevar Mac-A isolates which were identified in the first version of the assay as MAC and which were correctly identified as M. intracellulare by the AccuProbe system.

Equal to the new version of the INNO-LiPA, the GenoType Mycobacterium assay provides probes allowing simultaneous identification of M. tuberculosis complex, M. kansasii, M. xenopi, M. gordonae, M. avium, M. intracellulare, M. scrofulaceum, M. chelonae, M. malmoense, and M. celatum. The GenoType strip also includes specific probes for M. peregrinum and M. fortuitum and an additional probe for M. phlei.

In our study, four M. intracellulare isolates were correctly identified by the INNO-LiPA and GenoType assays. For one M. intracellulare isolate that was identified as M. intracellulare sequevar Mac-A by the LiPA assay, the GenoType showed a noninterpretable hybridization pattern (positive hybridization results with bands 2 and 10). Two MAC strains also gave the same noninterpretable hybridization pattern on the GenoType probe strip (positive for bands 2 and 10). These two isolates were identified to the genus level by INNO-LiPA. When tested with AccuProbe, these two isolates hybridized with MAC probes but not with probes specific for M. avium and M. intracellulare. The ITS sequences of these two strains were different and showed 100% homology with the Mac-U sequevar and 99% homology with the Mac-Q sequevar, respectively. All 11 M. avium strains tested were correctly identified by both systems. These results reflect the great genetic variation in the MAIS complex.

In our study, two MAC isolates and one M. intracellulare isolate were misidentified by GenoType, in all cases showing noninterpretable hybridization patterns.

All 14 M. kansasii strains tested were correctly identified by both tests. Moreover, the LiPA Mycobacteria assay provided further differentiation of M. kansasii to different genotypes (2).

One M. thermoresistibile strain was misidentified by both methods. The LiPA strip showed a hybridization pattern compatible with M. fortuitum-M. peregrinum complex, and the GenoType identified this isolate as M. celatum. The positive hybridization of the M. thermoresistibile isolate with the M. fortuitum probe on the LiPA test was confirmed by ITS nucleotide sequencing. This test indicated that there was a perfect match between the M. fortuitum probe and the ITS sequence of the M. thermoresistibile isolate. This cross-reaction has been reported previously by Tortoli et al. (24) in a recent article in which this new version of INNO-LiPA test was evaluated with a total of 197 mycobacteria belonging to 81 different taxa. Otherwise, 23S rRNA sequences for M. thermoresistibile and M. celatum are not closely related (20).

This GenoType cross-hybridization result could be due to either an inappropriate selection of the M. celatum probe region or an incorrect temperature during the hybridization procedure. Both tests require highly stringent hybridization conditions to ensure that the test is carried out properly. If the hybridization temperature is not adequate, several nonspecific bands are seen on the strips. In contrast to the study by Mäkinen et al. (7), in which the INNO-LiPA assay was more influenced by hybridization temperature variations than GenoType, in our study the latter assay appeared to be more susceptible to temperature changes. This fact could also explain the large number of samples (n = 8) that showed noninterpretable hybridization patterns on the GenoType strip (Table 1). One of these noninterpretable band patterns corresponded with an M. terrae isolate that showed a hybridization pattern similar to that of M. tuberculosis complex (positive for bands 1, 2, 10, and 16). Band 16 showed a weaker hybridization signal than band 10, and according to the package insert instructions, this pattern is considered a noninterpretable result.

One M. smegmatis isolate was misidentified as M. fortuitum II by the GenoType. A possible explanation for this identification mistake is the high degree of homology in the 23S rRNA sequence for these two mycobacterial species (20). Interestingly, one other M. smegmatis isolate was correctly identified by GenoType as nontuberculous mycobacteria. This fact probably reflects the genetic variation observed in mycobacterial subspecies isolated from different sources (5, 14).

Computing the mycobacterial species within the identification range of each test, the INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria v2.0 assay correctly identified 99% (99 of 100) of the mycobacterial isolates tested, while the Genotype correctly identified 94.7% (89 of 94).

Both mycobacterial identification methods performed similarly in the laboratory. The time required to complete them was similar, about 5 h. Otherwise, both tests have been shown to be sensitive and specific assays that allow precise identification of the majority of mycobacteria usually isolated in laboratories.

Although the INNO-LiPA and GenoType tests were rapid and reliable methods for mycobacterial identification, in this study INNO-LiPA was more sensitive and accurate than GenoType. Due to the number of mycobacterial species and the different species that can be identified with each method, the true clinical performance of these tests may also depend on the frequency of nontuberculous mycobacterial species isolated in each country.

Acknowledgments

We thank Innogenetics España (Barcelona, Spain) and Hain Diagnostika (Nehren, Germany) for providing the reagents for this study and Innogenetics (Ghent, Belgium) for technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe, C., S. Hosojima, Y. Fukasawa, Y. Kazumi, M. Takahashi, K. Hirano, and T. Mori. 1992. Comparison of MB-Check, Bactec, and egg-based media for recovery of mycobacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:878-881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alcaide, F., I. Richter, C. Bernasconi, B. Springer, C. Hagenau, R. Schulze-Röbbecke, E. Tortoli, R. Martín, E. C. Böttger, and A. Telenti. 1997. Heterogeneity and clonality among isolates of Mycobacterium kansasii: implications for epidemiological and pathogenicity studies. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1959-1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Evans, K. D., A. S. Nakasone, P. A. Sutherland, L. M. De la Maza, and E. M. Peterson. 1992. Identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium-M. intracellulare directly from primary BACTEC cultures by using acridinium-ester-labeled DNA probes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 30:2427-2431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirschner, P., B. Springer, U. Vogel, A. Meier, A. Wrede, M. Kiekenbeck, F. C. Bange, and E. C. Böttger. 1993. Genotypic identification of mycobacteria by nucleic acid sequence determination: report of a 2-year experience in a clinical laboratory. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:2882-2889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Legrand, E., C. Sola, B. Verdol, and N. Rastogi. 2000. Genetic diversity of Mycobacterium avium recovered from AIDS patients in the Caribbean as studied by a consensus IS1245-RFLP method and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. Res. Microbiol. 151:271283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luquin, M., V. Ausina, F. López-Calahorra, F. Belda, M. García-Barceló, C. Celma, and G. Prats. 1991. Evaluation of practical chromatography procedures for identification of clinical isolates of mycobacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29:120-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mäkinen, J., A. Sarkola, M. Marjamäki, M. K. Viljanen, and H. Soini. 2002. Evaluation of GenoType and LiPA Mycobacteria assays for identification of Finnish mycobacterial isolates. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:3478-3481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mijs, W., K. De Vreese, A. Devos, H. Pottel, A. Valgaeren, C. Evans, J. Norton, D. Parker, L. Rigouts, F. Portaels, U. Reischl, S. Watterson, G. Pfyffer, and R. Rossau. 2002. Evaluation of a commercial line probe assay for identification of Mycobacterium species from liquid and solid culture. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 21:794-802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mijs, W., P. de Haas, R. Rossau, T. Van der Laan, L. Rigouts, F. Portaels, and D. Van Soolingen. 2002. Molecular evidence to support a proposal to reverse the designation Mycobacterium avium subsp. avium for bird-type isolates and M. avium subsp. hominissuis for the human/porcine type of M. avium. Int. J. Syst. E vol. Microbiol. 52:1505-1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller, N., S. Infante, and T. Cleary. 2000. Evaluation of the LiPA Mycobacteria assay for identification of mycobacterial species from Bactec 12B bottles. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:1915-1919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Padilla, E., J. M. Manterola, V. González, J. Lonca, J. Domínguez, L. Matas, N. Galí, and V. Ausina. 2001. Rapid detection of several mycobacterial species using a polymerase chain reaction reverse hybridisation assay. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 20:661-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Padilla, E., J. M. Manterola, O. F. Rasmussen, J. Lonca, J. Domínguez, L. Matas, A. Hernández, and V. Ausina. 2000. Evaluation of a fluorescence hybridisation assay using peptide nucleic acid probes for identification and differentiation of tuberculous and non-tuberculous mycobacteria in liquid cultures. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 19:140-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Padilla, E., V. González, J. M. Manterola, J. Lonca, A. Pérez, L. Matas, M. D. Quesada, and V. Ausina. 2003. Evaluation of two different cell lysis methods for releasing mycobacterial nucleic acids in the INNO LiPA mycobacteria test. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 46:19-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Picardeau, M., G. Prod'Hom, L. Raskine, M. P. LePennec, and V. Vincent. 1997. Genotypic characterization of five subspecies of Mycobacterium kansasii. J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:25-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rastogi, N., E. Legrand, and C. Sola. 2001. The mycobacteria: an introduction to nomenclature and pathogenesis. Rev. Sci. Technol. 20:21-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reisner, B. S., A. M. Gatson, and G. L. Woods. 1994. Use of Gen-Probe AccuProbes to identify Mycobacterium avium complex, Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, Mycobacterium kansasii, and Mycobacterium gordonae directly from BACTEC TB broth cultures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:2995-2998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richmond, J. Y., and R. W. McKinney. 1993. Biosafety in microbiological and biomedical laboratories. HHS publication no. CDC 93-8395. Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, Ga.

- 18.Scarparo, C., P. Piccoli, A. Rigon, G. Ruggiero, D. Nista, and C. Piersimoni. 2001. Direct identification of mycobacteria from MB/BacT Alert 3D bottles: comparative evaluation of two commercial probe assays. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3222-3227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stender, H., K. Lund, K. H. Petersen, O. F. Rasmussen, P. Hongmanee, H. Miörner, and S. E. Godtfredsen. 1999. Fluorescence in situ hybridization assay using peptide nucleic acid probes for differentiation between tuberculous and non-tuberculous Mycobacterium species in smears of mycobacterium cultures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2760-2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stone, B. B., R. M. Nietupski, G. L. Breton, and W. G. Weisburg. 1995. Comparison of Mycobacterium 23S rRNA sequences by high-temperature reverse transcription and PCR. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:811-819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suffys, P. N., A da Silva Rocha, M. de Oliveira, C. E. Dias Campos, A. M. Werneck Barreto, F. Portaels, L. Rigouts, G. Wouters, G. Jannes, G. van Reybroeck, W. Mijs, and B. Vanderborght. 2001. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level using the INNO LiPA Mycobacteria, a reverse hybridization assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:4477-4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Telenti, A., F. Marchesi, M. Balz, F. Bally, E. C. Böttger, and T. Bodmer. 1993. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31:175-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tortoli, E., A. Nanetti, C. Piersimoni, P. Cichero, C. Farina, G. Mucignat, C. Scarparo, L. Bartolini, R. Valentini, D. Nista, G. Gesu, C. P. Tosi, M. Crovatto, and G. Brusarosco. 2001. Performance assessment of a new multiplex probe assay for identification of mycobacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:1079-1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tortoli, E., A. Mariottini, and G. Mazzarelli. 2003. Evaluation of INNO-LiPA Mycobacteria v2: improved reverse hybridization multiple DNA probe assay for mycobacterial identification. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:4418-4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]