Abstract

Metal halides perovskites, such as hybrid organic–inorganic CH3NH3PbI3, are newcomer optoelectronic materials that have attracted enormous attention as solution-deposited absorbing layers in solar cells with power conversion efficiencies reaching 20%. Herein we demonstrate a new avenue for halide perovskites by designing highly luminescent perovskite-based colloidal quantum dot materials. We have synthesized monodisperse colloidal nanocubes (4–15 nm edge lengths) of fully inorganic cesium lead halide perovskites (CsPbX3, X = Cl, Br, and I or mixed halide systems Cl/Br and Br/I) using inexpensive commercial precursors. Through compositional modulations and quantum size-effects, the bandgap energies and emission spectra are readily tunable over the entire visible spectral region of 410–700 nm. The photoluminescence of CsPbX3 nanocrystals is characterized by narrow emission line-widths of 12–42 nm, wide color gamut covering up to 140% of the NTSC color standard, high quantum yields of up to 90%, and radiative lifetimes in the range of 1–29 ns. The compelling combination of enhanced optical properties and chemical robustness makes CsPbX3 nanocrystals appealing for optoelectronic applications, particularly for blue and green spectral regions (410–530 nm), where typical metal chalcogenide-based quantum dots suffer from photodegradation.

Keywords: Perovskites, halides, quantum dots, nanocrystals, optoelectronics

Colloidal semiconductor nanocrystals (NCs, typically 2–20 nm large), also known as nanocrystal quantum dots (QDs), are being studied intensively as future optoelectronic materials.1−4 These QD materials feature a very favorable combination of quantum-size effects, enhancing their optical properties with respect to their bulk counterparts, versatile surface chemistry, and a “free” colloidal state, allowing their dispersion into a variety of solvents and matrices and eventual incorporation into various devices. To date, the best developed optoelectronic NCs in terms of size, shape, and composition are binary and multinary (ternary, quaternary) metal chalcogenide NCs.1,5−9 In contrast, the potential of semiconducting metal halides in the form of colloidal NCs remains rather unexplored. In this regard, recent reports on highly efficient photovoltaic devices with certified power conversion efficiencies approaching 20% using hybrid organic–inorganic lead halides MAPbX3 (MA = CH3NH3, X = Cl, Br, and I) as semiconducting absorber layers are highly encouraging.10−14

In this study, we turn readers’ attention to a closely related family of materials: all-inorganic cesium lead halide perovskites (CsPbX3, X = Cl, Br, I, and mixed Cl/Br and Br/I systems; isostructural to perovskite CaTiO3 and related oxides). These ternary compounds are far less soluble in common solvents (contrary to MAPbX3), which is a shortcoming for direct solution processing but a necessary attribute for obtaining these compounds in the form of colloidal NCs. Although the synthesis, crystallography, and photoconductivity of direct bandgap CsPbX3 have been reported more than 50 years ago,15 they have never been explored in the form of colloidal nanomaterials.

Here we report a facile colloidal synthesis of monodisperse, 4–15 nm CsPbX3 NCs with cubic shape and cubic perovskite crystal structure. CsPbX3 NCs exhibit not only compositional bandgap engineering, but owing to the exciton Bohr diameter of up to 12 nm, also exhibit size-tunability of their bandgap energies through the entire visible spectral region of 410–700 nm. Photoluminescence (PL) of CsPbX3 NCs is characterized by narrow emission line widths of 12–42 nm, high quantum yields of 50–90%, and short radiative lifetimes of 1–29 ns.

Synthesis of Monodisperse CsPbX3 NCs

Our solution-phase synthesis of monodisperse CsPbX3 NCs (Figure 1) takes advantage of the ionic nature of the chemical bonding in these compounds. Controlled arrested precipitation of Cs+, Pb2+, and X– ions into CsPbX3 NCs is obtained by reacting Cs-oleate with a Pb(II)-halide in a high boiling solvent (octadecene) at 140–200 °C (for details, see the Supporting Information). A 1:1 mixture of oleylamine and oleic acid are added into octadecene to solubilize PbX2 and to colloidally stabilize the NCs. As one would expect for an ionic metathesis reaction, the nucleation and growth kinetics are very fast. In situ PL measurements with a CCD-array detector (Supporting Information Figure S1) indicate that the majority of growth occurs within the first 1–3 s (faster for heavier halides). Consequently, the size of CsPbX3 NCs can be most conveniently tuned in the range of 4–15 nm by the reaction temperature (140–200 °C) rather than by the growth time. Mixed-halide perovskites, that is, CsPb(Cl/Br)3 and CsPb(Br/I)3, can be readily produced by combining appropriate ratios of PbX2 salts. Note that Cl/I perovskites cannot be obtained due to the large difference in ionic radii, which is in good agreement with the phase diagram for bulk materials.16 Elemental analyses by energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy and by Ratherford backscattering spectrometry (RBS) confirmed the 1:1:3 atomic ratio for all samples of CsPbX3 NCs, including mixed-halide systems.

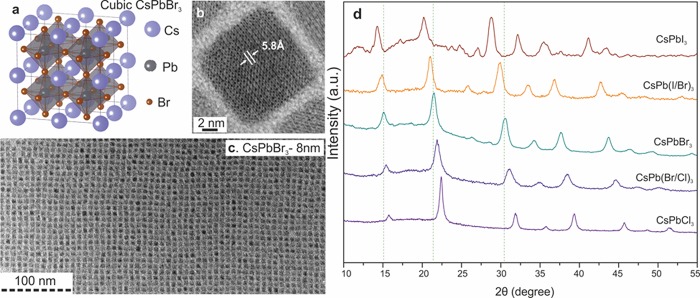

Figure 1.

Monodisperse CsPbX3 NCs and their structural characterization. (a) Schematic of the cubic perovskite lattice; (b,c) typical transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of CsPbBr3 NCs; (d) X-ray diffraction patterns for typical ternary and mixed-halide NCs.

CsPbX3 are known to crystallize in orthorhombic, tetragonal, and cubic polymorphs of the perovskite lattice with the cubic phase being the high-temperature state for all compounds.16−18 Interestingly, we find that all CsPbX3 NCs crystallize in the cubic phase (Figure 1d), which can be attributed to the combined effect of the high synthesis temperature and contributions from the surface energy. For CsPbI3 NCs, this is very much a metastable state, because bulk material converts into cubic polymorph only above 315 °C. At room temperature, an exclusively PL-inactive orthorhombic phase has been reported for bulk CsPbI3 (a yellow phase).16−19 Our first-principles total energy calculations (density functional theory, Figure S2, Table S1 in Supporting Information) confirm the bulk cubic CsPbI3 phase to have 17 kJ/mol higher internal energy than the orthorhombic polymorph (7 kJ/mol difference for CsPbBr3). Weak emission centered at ∼710 nm has been observed from melt-spun bulk CsPbI3, shortly before recrystallization into the yellow phase.18 Similarly, our solution synthesis of CsPbI3 at 305 °C yields cubic-phase 100–200 nm NCs with weak, short-lived emission at 714 nm (1.74 eV), highlighting the importance of size reduction for stabilizing the cubic phase and indicating that all CsPbI3 NCs in Figure 2b (5–15 nm in size) exhibit quantum-size effects (i.e., higher band gap energies due to quantum confinement, as discussed below). Cubic 4–15 nm CsPbI3 NCs recrystallize into the yellow phase only upon extended storage (months), whereas all other compositions of CsPbX3 NCs appear fully stable in a cubic phase.

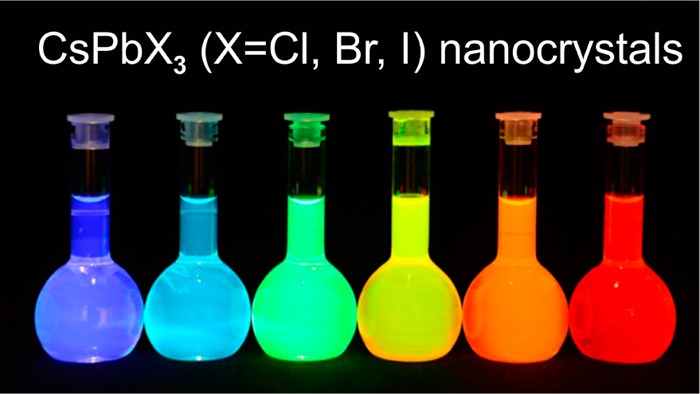

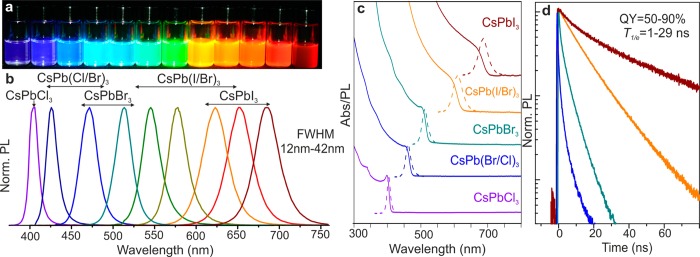

Figure 2.

Colloidal perovskite CsPbX3 NCs (X = Cl, Br, I) exhibit size- and composition-tunable bandgap energies covering the entire visible spectral region with narrow and bright emission: (a) colloidal solutions in toluene under UV lamp (λ = 365 nm); (b) representative PL spectra (λexc = 400 nm for all but 350 nm for CsPbCl3 samples); (c) typical optical absorption and PL spectra; (d) time-resolved PL decays for all samples shown in (c) except CsPbCl3.

Optical Properties of Colloidal CsPbX3 NCs

Optical absorption and emission spectra of colloidal CsPbX3 NCs (Figure 2b,c) can be tuned over the entire visible spectral region by adjusting their composition (ratio of halides in mixed halide NCs) and particle size (quantum-size effects). Remarkably bright PL of all NCs is characterized by high QY of 50–90% and narrow emission line widths of 12–42 nm. The combination of these two characteristics had been previously achieved only for core–shell chalcogenide-based QDs such as CdSe/CdS due to the narrow size distributions of the luminescent CdSe cores, combined with an epitaxially grown, electronically passivating CdS shell.5,20 Time-resolved photoluminescence decays of CsPbX3 NCs (Figure 2d) indicate radiative lifetimes in the range of 1–29 ns with faster emission for wider-gap NCs. For comparison, decay times of several 100 ns are typically observed in MAPbI3 (PL peak at 765 nm, fwhm = 50 nm)21 and 40–400 ns for MAPbBr3–xClx (x = 0.6–2).22

Very bright emission of CsPbX3 NCs indicates that contrary to uncoated chalcogenide NCs surface dangling bonds do not impart severe midgap trap states. This observation is also in good agreement with the high photophysical quality of hybrid organic–inorganic perovskites (MAPbX3), despite their low-temperature solution-processing, which is generally considered to cause a high density of structural defects and trap states. In particular, thin-films of MAPbX3 exhibit relatively high PL QYs of 20–40% at room temperature23,24 and afford inexpensive photovoltaic devices approaching 20% in power conversion efficiency10−12 and also electrically driven light-emitting devices.25

Ternary CsPbX3 NCs compare favorably to common multinary chalcogenide NCs: both ternary (CuInS2, CuInSe2, AgInS2, and AgInSe2) and quaternary (CuZnSnS2 and similar) compounds. CsPbX3 materials are highly ionic and thus are rather stoichiometric and ordered due to the distinct size and charge of the Cs and Pb ions. This is different from multinary chalcogenide materials that exhibit significant disorder and inhomogeneity in the distribution of cations and anions owing to little difference between the different cationic and anionic sites (all are essentially tetrahedral). In addition, considerable stoichiometric deviations lead to a large density of donor–acceptor states due to various point defects (vacancies, interstitials, etc.) within the band gap, both shallow and deep. These effects eventually lead to absent or weak and broad emission spectra and long multiexponent lifetimes.7,26−29

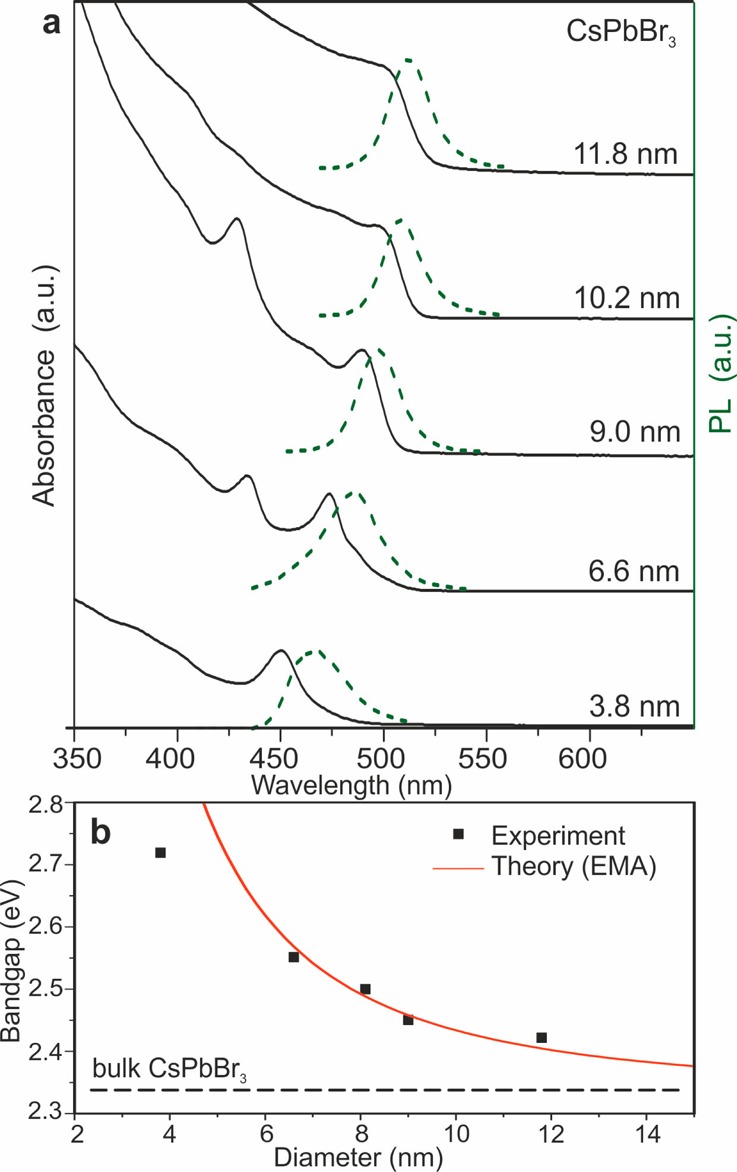

For a colloidal semiconductor NC to exhibit quantum-dot-like properties (shown in Figures 2b and 3), the NC diameter must be comparable or smaller than that of the natural delocalization lengths of an exciton in a bulk semiconductor (i.e., the exciton Bohr diameter, a0). The electronic structure of CsPbX3 (X = Cl, Br, and I), including scalar relativistic and spin–orbit interactions, was calculated using VASP code30 and confirms that the upper valence band is formed predominately by the halide p-orbitals and the lower conduction band is formed by the overlap of the Pb p-orbitals (Figures S3 and S4 and Tables S2 and S3 in Supporting Information). Effective masses of the electrons and holes were estimated from the band dispersion, while the high-frequency dielectric constants were calculated by using density functional perturbation theory.31 Within the effective mass approximation (EMA),32 we have estimated the effective Bohr diameters of Wannier–Mott excitons and the binding energies for CsPbCl3 (5 nm, 75 meV), CsPbBr3 (7 nm, 40 meV), and CsPbI3 (12 nm, 20 meV). Similarly, in closely related hybrid perovskite MAPbI3 small exciton binding energies of ≤25 meV have been suggested computationally33−35 and found experimentally.36 For comparison, the typical exciton binding energies in organic semiconductors are above 100 meV. The confinement energy (ΔE = ℏ2π2/2m*r2, where r is the particle radius and m* is the reduced mass of the exciton) provides an estimate for the blue shift of the emission peak and absorption edge and is in good agreement with the experimental observations (Figure 3b).

Figure 3.

(a) Quantum-size effects in the absorption and emission spectra of 5–12 nm CsPbBr3 NCs. (b) Experimental versus theoretical (effective mass approximation, EMA) size dependence of the band gap energy.

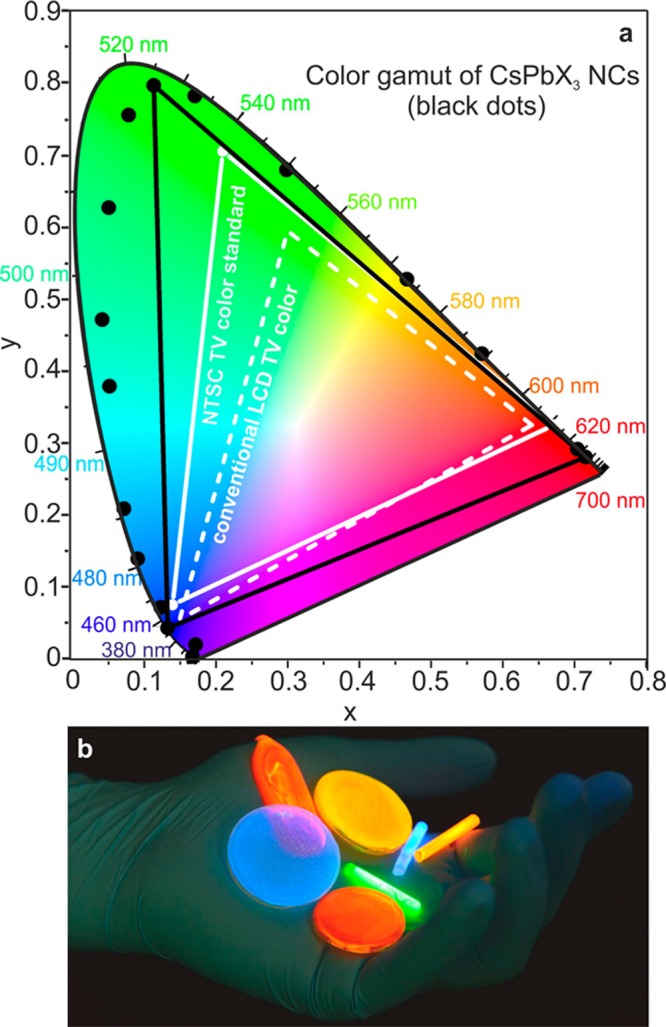

Recently, highly luminescent semiconductor NCs based on Cd-chalcogenides have inspired innovative optoelectronic applications such as color-conversion LEDs, color-enhancers in backlight applications (e.g., Sony’s 2013 Triluminos LCD displays), and solid-state lighting.4,37,38 Compared to conventional rare-earth phosphors or organic polymers and dyes, NCs often show superior quantum efficiency and narrower PL spectra with fine-size tuning of the emission peaks and hence can produce saturated colors. A CIE chromaticity diagram (introduced by the Commision Internationale de l’Eclairage)39 allows the comparison of the quality of colors by mapping colors visible to the human eye in terms of hue and saturation. For instance, well-optimized core–shell CdSe-based NCs cover ≥100% of the NTSC TV color standard (introduced in 1951 by the National Television System Committee).39 Figure 4a shows that CsPbX3 NCs allow a wide gamut of pure colors as well. Namely, a selected triangle of red, green, and blue emitting CsPbX3 NCs encompasses 140% of the NTSC standard, extending mainly into red and green regions.

Figure 4.

(a) Emission from CsPbX3 NCs (black data points) plotted on CEI chromaticity coordinates and compared to most common color standards (LCD TV, dashed white triangle, and NTSC TV, solid white triangle). Radiant Imaging Color Calculator software from Radiant Zemax (http://www.radiantzemax.com) was used to map the colors. (b) Photograph (λexc = 365 nm) of highly luminescent CsPbX3 NCs-PMMA polymer monoliths obtained with Irgacure 819 as photoinitiator for polymerization.

Light-emission applications, discussed above, and also luminescent solar concentrators40,41 require solution-processability and miscibility of NC-emitters with organic and inorganic matrix materials. To demonstrate such robustness for CsPbX3 NCs, we embedded them into poly(methylmetacrylate) (PMMA), yielding composites of excellent optical clarity and with bright emission (Figure 4b). To accomplish this, CsPbX3 NCs were first dispersed in a liquid monomer (methylmetacrylate, MMA) as a solvent. Besides using known heat-induced polymerization with radical initiators,41 we also performed polymerization already at room-temperature by adding a photoinitiator Irgacure 819 (bis(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)-phenylphosphineoxide),42 followed by 1h of UV-curing. We find that the presence of CsPbX3 NCs increases the rate of photopolymerization, compared to a control experiment with pure MMA. This can be explained by the fact that the luminescence from CsPbX3 NCs may be reabsorbed by the photoinitiator that has a strong absorption band in the visible spectral region, increasing the rate of polymerization.

Conclusions

In summary, we have presented highly luminescent colloidal CsPbX3 NCs (X = Cl, Br, I, and mixed Cl/Br and Br/I systems) with bright (QY = 50–90%), stable, spectrally narrow, and broadly tunable photoluminescence. Particularly appealing are highly stable blue and green emitting CsPbX3 NCs (410–530 nm), because the corresponding metal-chalcogenide QDs show reduced chemical and photostability at these wavelengths. In our ongoing experiments, we find that this simple synthesis methodology is also applicable to other metal halides with related crystal structures (e.g., CsGeI3, Cs3Bi2I9, and Cs2SnI6, to be published elsewhere). Future studies with these novel QD-materials will concentrate on optoelectronic applications such as lasing, light-emitting diodes, photovoltaics, and photon detection.

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the European Research Council (ERC) via Starting Grant (306733). The work at Bath was supported by the ERC Starting Grant (277757) and by the EPSRC (Grants EP/M009580/1 and EP/K016288/1). Calculations at Bath were performed on ARCHER via the U.K.’s HPC Materials Chemistry Consortium (Grant EP/L000202). Calculations at ETH Zürich were performed on the central HPC cluster BRUTUS. We thank Nadia Schwitz for a help with photography, Professor Dr. H. Grützmacher and Dr. G. Müller for a sample of Irgacure 819 photoinitiator, Dr. F. Krumeich for EDX measurements, Dr. M. Döbeli for RBS measurements (ETH Laboratory of Ion Beam Physics), and Dr. N. Stadie for reading the manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge the support of the Electron Microscopy Center at Empa and the Scientific Center for Optical and Electron Microscopy (ScopeM) at ETH Zürich.

Supporting Information Available

Synthesis details, calculations, and additional figures. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was prepared through the contribution of all coauthors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Notes

This article has an ACS LiveSlides multimedia presentation available.

This paper was published on the Web on February 2, 2015. The discussion of the preparation of Cs-oleate and synthesis of CsPbX3 NCs in the Supporting Information has been corrected, and the paper was reposted on April 14, 2015.

Supplementary Material

References

- Talapin D. V.; Lee J.-S.; Kovalenko M. V.; Shevchenko E. V. Chem. Rev. 2009, 110, 389–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan X.; Masala S.; Sargent E. H. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 233–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetsch F.; Zhao N.; Kershaw S. V.; Rogach A. L. Mater. Today 2013, 16, 312–325. [Google Scholar]

- Shirasaki Y.; Supran G. J.; Bawendi M. G.; Bulovic V. Nat. Photonics 2013, 7, 13–23. [Google Scholar]

- Chen O.; Zhao J.; Chauhan V. P.; Cui J.; Wong C.; Harris D. K.; Wei H.; Han H.-S.; Fukumura D.; Jain R. K.; Bawendi M. G. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 445–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C. B.; Norris D. J.; Bawendi M. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 8706–8715. [Google Scholar]

- Aldakov D.; Lefrancois A.; Reiss P. J. Mater. Chem. C 2013, 1, 3756–3776. [Google Scholar]

- Fan F.-J.; Wu L.; Yu S.-H. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 190–208. [Google Scholar]

- Yu X.; Shavel A.; An X.; Luo Z.; Ibáñez M.; Cabot A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 9236–9239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratzel M. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 838–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M. A.; Ho-Baillie A.; Snaith H. J. Nat. Photonics 2014, 8, 506–514. [Google Scholar]

- Park N.-G. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 2423–2429. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H.; Chen Q.; Li G.; Luo S.; Song T.-b.; Duan H.-S.; Hong Z.; You J.; Liu Y.; Yang Y. Science 2014, 345, 542–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung I.; Lee B.; He J.; Chang R. P. H.; Kanatzidis M. G. Nature 2012, 485, 486–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller C. K. Nature 1958, 182, 1436–1436. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S.; Weiden N.; Weiss A. Z. Phys. Chem. 1992, 175, 63–80. [Google Scholar]

- Trots D. M.; Myagkota S. V. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2008, 69, 2520–2526. [Google Scholar]

- Stoumpos C. C.; Malliakas C. D.; Kanatzidis M. G. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 9019–9038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babin V.; Fabeni P.; Nikl M.; Nitsch K.; Pazzi G. P.; Zazubovich S. Phys. Status Solidi B 2001, 226, 419–428. [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou S.; Vaccaro G.; Pinchetti V.; De Donato F.; Grim J. Q.; Casu A.; Genovese A.; Vicidomini G.; Diaspro A.; Brovelli S.; Manna L.; Moreels I. J. Mater. Chem. C 2014, 2, 3439–3447. [Google Scholar]

- Wehrenfennig C.; Liu M.; Snaith H. J.; Johnston M. B.; Herz L. M. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 1300–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M.; Yu H.; Lyu M.; Wang Q.; Yun J.-H.; Wang L. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 11727–11730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing G.; Mathews N.; Lim S. S.; Yantara N.; Liu X.; Sabba D.; Grätzel M.; Mhaisalkar S.; Sum T. C. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 476–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschler F.; Price M.; Pathak S.; Klintberg L. E.; Jarausch D.-D.; Higler R.; Hüttner S.; Leijtens T.; Stranks S. D.; Snaith H. J.; Atatüre M.; Phillips R. T.; Friend R. H. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 1421–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Z.-K.; Moghaddam R. S.; Lai M. L.; Docampo P.; Higler R.; Deschler F.; Price M.; Sadhanala A.; Pazos L. M.; Credgington D.; Hanusch F.; Bein T.; Snaith H. J.; Friend R. H. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014, 9, 687–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueng H. Y.; Hwang H. L. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 1989, 50, 1297–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Huang L.; Zhu X.; Publicover N. G.; Hunter K. W.; Ahmadiantehrani M.; de Bettencourt-Dias A.; Bell T. W. J. Nanopart. Res. 2013, 15, 2056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Trizio L.; Prato M.; Genovese A.; Casu A.; Povia M.; Simonutti R.; Alcocer M. J. P.; D’Andrea C.; Tassone F.; Manna L. Chem. Mater. 2012, 24, 2400–2406. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W.; Zhong X. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 4065–4072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kresse G.; Joubert D. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 59, 1758. [Google Scholar]

- Baroni S.; de Gironcoli S.; Dal Corso A.; Giannozzi P. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2001, 73, 515. [Google Scholar]

- Yu P. Y.; Cardona M.. Fundamentals of Semiconductors; Springer: New York, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Even J.; Pedesseau L.; Katan C. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 11566–11572. [Google Scholar]

- Frost J. M.; Butler K. T.; Brivio F.; Hendon C. H.; van Schilfgaarde M.; Walsh A. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 2584–2590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menéndez-Proupin E.; Palacios P.; Wahnón P.; Conesa J. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 045207. [Google Scholar]

- Saba M.; Cadelano M.; Marongiu D.; Chen F.; Sarritzu V.; Sestu N.; Figus C.; Aresti M.; Piras R.; Geddo Lehmann A.; Cannas C.; Musinu A.; Quochi F.; Mura A.; Bongiovanni G. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T.-H.; Jun S.; Cho K.-S.; Choi B. L.; Jang E. MRS Bull. 2013, 38, 712–720. [Google Scholar]

- Supran G. J.; Shirasaki Y.; Song K. W.; Caruge J.-M.; Kazlas P. T.; Coe-Sullivan S.; Andrew T. L.; Bawendi M. G.; Bulović V. MRS Bull. 2013, 38, 703–711. [Google Scholar]

- Ye S.; Xiao F.; Pan Y. X.; Ma Y. Y.; Zhang Q. Y. Mater. Sci. Eng. R 2010, 71, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bomm J.; Buechtemann A.; Chatten A. J.; Bose R.; Farrell D. J.; Chan N. L. A.; Xiao Y.; Slooff L. H.; Meyer T.; Meyer A.; van Sark W. G. J. H. M.; Koole R. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2011, 95, 2087–2094. [Google Scholar]

- Meinardi F.; Colombo A.; Velizhanin K. A.; Simonutti R.; Lorenzon M.; Beverina L.; Viswanatha R.; Klimov V. I.; Brovelli S. Nat. Photonics 2014, 8, 392–399. [Google Scholar]

- Gruetzmacher H.; Geier J.; Stein D.; Ott T.; Schoenberg H.; Sommerlade R. H.; Boulmaaz S.; Wolf J.-P.; Murer P.; Ulrich T. Chimia 2008, 62, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.