Abstract

Setting:

All tuberculosis (TB) diagnostic and treatment centres in Fiji.

Objectives:

To report on pre-treatment loss to follow-up rates over a 10-year period (2001–2010) and to examine if patients’ age, sex and geographic origin are associated with the observed shortcomings in the health services.

Methods:

A retrospective review of routine programme data reconciling TB laboratory and treatment registers.

Results:

A total of 690 sputum smear-positive TB patients were diagnosed in the laboratory, of whom 579 (84%) were started on anti-tuberculosis treatment—an overall pre-treatment loss to follow-up of 111 (16%). Peak loss to follow-up rates were seen in 2003, 2004 and 2010. Pre-treatment losses were all aged ≥15 years. In the Western Division of Fiji, 33% of sputum-positive patients were declared pre-treatment loss to follow-up; this division had over five times the risk of such an adverse outcome compared to the Central Division (OR 5.2, 95%CI 3.1–8.9, P < 0.0001).

Conclusion:

This study has identified an important shortcoming in programme linkage, communication and feedback between TB diagnostic and treatment services, leading to high pre-treatment loss to follow-up rates. This negatively influences TB services, and ways to rectify this situation are discussed.

Keywords: operational research, pre-treatment loss to follow-up, tuberculosis, laboratory register, Fiji

Abstract

Contexte:

Tous les centres de diagnostic et de traitement de la tuberculose (TB) aux Iles Fiji.

Objectif:

Signaler les taux de pertes de suivi avant traitement sur une période de 10 ans (2001–2010) et examiner dans quelle mesure l’âge, le sexe et l’origine géographique des patients sont en association avec cette déficience du service de santé.

Méthodes :Revue rétrospective des données de routine du programme avec recoupement des registres de laboratoire et de traitement.

Resultats:

Au total, 690 patients TB à frottis positif des crachats ont été diagnostiqués au laboratoire, parmi lesquels 579 (84%) ont été mis sous traitement antituberculeux, ce qui fournit une perte globale du suivi avant traitement de 111 sujets (16%). Des pics des taux de perte de suivi ont été observés en 2003, 2004 et 2010. Les pertes avant traitement concernaient des patients âgés de ≥15 ans. Dans la Division Ouest des Iles Fiji, 33% des patients à frottis positif des crachats ont été déclarés comme perdus de vue avant traitement, et dans cette division le risque de ce résultat défavorable a été cinq fois supérieur à celui de la Division Centrale (OR 5,2 ; IC 3,1–8,9 ; P < 0,0001).

Conclusion:

Cette étude a identifié une déficience importante dans le recoupement des programmes, la communication et le retour d’information entre les services de diagnostic et de traitement de la TB, entrainant des taux élevés de perte de suivi avant traitement. Ceci influence les services TB de façon négative. La discussion porte sur les moyens de rectifier la situation.

Abstract

Marco de referencia:

Todos los centros de diagnóstico y tratamiento de la tuberculosis (TB) en Fiji.

Objetivo:

Documentar las tasas de pérdida temprana de pacientes con TB durante el seguimiento, antes de comenzar el tratamiento, en un período de 10 años (del 2001 al 2010) y analizar si la edad, el sexo y la procedencia geográfica de los pacientes se correlacionan con estas fallas en el servicio de salud.

Métodos:

Se llevó a cabo un examen retrospectivo de los datos corrientes del programa y se buscó la correspondencia de la información del laboratorio de TB con los datos del registro de tratamiento antituberculoso.

Resultados:

En el laboratorio se diagnosticaron 690 casos de TB con baciloscopia positiva, de los cuales 579 comenzaron el tratamiento antituberculoso (84%), lo cual corresponde a una pérdida de 111 casos durante el seguimiento temprano antes del tratamiento (16%). Las proporciones más altas de pérdida se presentaron en el 2003, el 2004 y el 2010; los casos perdidos correspondieron a pacientes ≥ de 15 años de edad. En la división occidental de Fiji se declaró una pérdida de 33% de los pacientes con baciloscopia positiva antes de comenzar el tratamiento; esta división presentó un riesgo cinco veces mayor de desenlace clínico desfavorable en comparación con la división central (cociente de posibilidades 5,2; intervalo de confianza del 95% de 3,1 a 8,9; P < 0,0001).

Conclusión:

En el presente estudio se pusieron en evidencia graves deficiencias al comparar los datos del programa, la comunicación y la retroalimentación entre los servicios de diagnóstico y tratamiento de la TB, lo cual da origen a altas tasas de pérdida temprana de pacientes durante el seguimiento, antes comenzar el tratamiento. Esta situación tiene repercusiones negativas en el desempeño de los servicios de atención de la TB. En el artículo se analizan los mecanismos que permitirían rectificar estas insuficiencias.

Globally, under the National Tuberculosis Programme (NTP), a patient who does not appear in the tuberculosis (TB) treatment register after having been diagnosed with sputum smear-positive pulmonary TB (PTB), and thus is not initiated on anti-tuberculosis treatment, is known as a ‘pre-treatment loss to follow-up’.1 These patients were previously referred to as ‘initial defaulters’.2 From the perspective of the TB services, ‘pre-treatment loss to follow-up’ is important for two main reasons. First, untreated smear-positive PTB patients are infectious and may transmit TB to others in the community, constituting an important public health risk. Second, if and when such patients are identified in the health services, their illness is likely to have progressed and this can negatively influence their treatment outcome.

Previous studies in Africa and Asia have reported pre-treatment loss to follow-up rates of 5% to 25%, and various associated factors have been identified.3–8 In the Pacific Islands, there is no published information about the extent of this problem, nor whether patients’ socio-demographic characteristics and geographic access to TB diagnostic and treatment facilities might influence pre-treatment loss to follow-up rates. Such information would be useful to assess and improve programme performance. Fiji is a Pacific Island country that has been implementing the DOTS strategy since 1997.9 There are an estimated 23 TB cases per 100 000 population, of which ∼10/100 000 are smear-positive PTB cases.

We therefore 1) report pre-treatment loss to follow-up rates over a 10-year period (2001–2010) in Fiji, and 2) examine if patients’ age, sex and geographic origin are associated with the observed shortcomings in the health services.

METHODS

Study design

This was a retrospective review of routine NTP data.

Study setting and sites

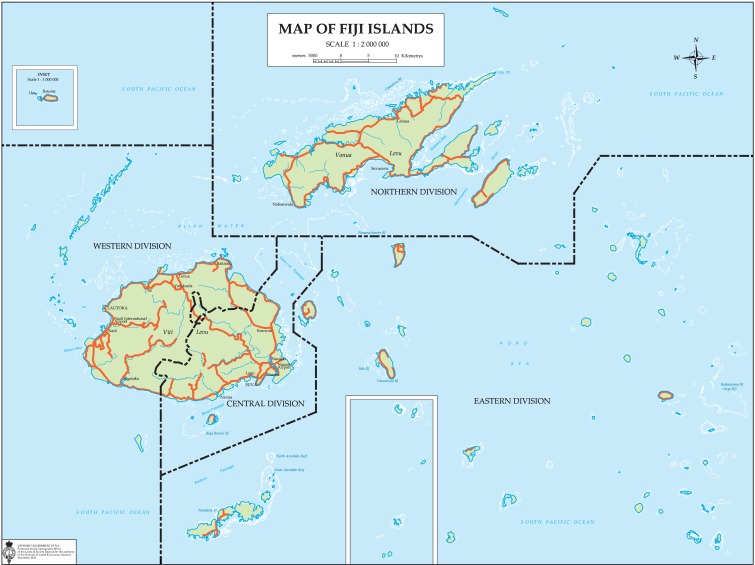

Fiji occupies an archipelago of about 322 islands, of which 106 have permanent inhabitants, and 522 islets. The country has two major islands, Viti Levu and Vanua Levu, which account for 87% of the population. In 2008, the country had an estimated population of 840 000. Fiji is divided into four geographic divisions, namely Central, Eastern, Northern and Western (Figure).

FIGURE.

Map of Fiji showing the geographic divisions.

Until 2010, there were only two DOTS centres providing TB registration and treatment in the country: the P J Twomey Hospital and the Lautoka Hospital, located respectively in the Central and Western Divisions of Fiji. There are four laboratories in the country that provide sputum smear microscopy services: these include the above-mentioned two centres, the Colonial War Memorial Hospital (the largest hospital in the country, located in the Central Division) and the Labasa Hospital (located in the Northern Division). TB diagnosis and treatment cannot be obtained anywhere else in the country other than at these centres.

Laboratory diagnosis and registration of pulmonary tuberculosis patients

A person with a cough of >2 weeks is considered a ‘possible case of TB’, and is required to submit three sputum specimens for smear microscopy. Smear-positive PTB is diagnosed on the basis of one or more acid-fast tubercle bacilli found in at least one sputum smear sample. All persons who undergo sputum smear examination are recorded in the laboratory register, as are the results of the sputum smear. All sputum smear-positive TB cases are then supposed to be referred to one of the two TB treatment centres, recorded in the TB treatment register and started on anti-tuberculosis treatment.

Study population and identification of pre-treatment loss to follow-up

All patients found to be sputum smear-positive in the sputum laboratory registers of the four laboratories from 2001 to 2010 were included in the study. The TB treatment registers were carefully reconciled with the laboratory registers. A patient who was sputum-positive on the laboratory register but not found on the TB treatment register was declared as ‘pre-treatment loss to follow-up’.

Data and statistical analysis

The following data were collected from the laboratory registers: year, socio-demographic characteristics (including name) and geographic residence. Data were entered into EpiData (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark) and cross-checked for consistency; discrepancies were corrected by referring to the original records. Risk of pre-treatment loss to follow-up was measured using crude odds ratios (ORs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The level of significance was set at 5%.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Fiji National Research Ethics Committee and the Ethics Advisory Group of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France.

RESULTS

During the period 2001–2010, a total of 690 sputum smear-positive TB patients were diagnosed in the laboratory, of whom 579 (84%) were started on anti-tuberculosis treatment—an overall pre-treatment loss to follow-up of 111 (16%). The trend in pre-treatment loss to follow-up over the 10-year period is shown in Table 1. Peak loss-to-follow-up rates were seen in 2003, 2004 and 2010. Patients lost to follow-up were all aged ≥15 years (Table 2). From the Western Division of Fiji, 33% of sputum-positive patients were declared pre-treatment loss to follow-up and had over five times the risk of such an outcome compared to the Central Division (OR 5.2, 95%CI 3.1–8.9, P < 0.0001).

TABLE 1.

Pre-treatment loss to follow-up in smear-positive pulmonary TB patients, Fiji, 2001–2010

| Year | TB patients in laboratory register n | Patients in TB treatment register n | Pre-treatment loss to follow-up n (%) |

| 2001 | 62 | 50 | 12 (11) |

| 2002 | 86 | 75 | 11 (10) |

| 2003 | 65 | 49 | 16 (14) |

| 2004 | 64 | 45 | 19 (17) |

| 2005 | 59 | 47 | 12 (11) |

| 2006 | 72 | 61 | 11 (10) |

| 2007 | 59 | 52 | 7 (6) |

| 2008 | 77 | 72 | 5 (5) |

| 2009 | 59 | 55 | 4 (4) |

| 2010 | 87 | 73 | 14 (13) |

| Total | 690 | 579 | 111 (16) |

TB = tuberculosis.

TABLE 2.

Risk factors associated with pre-treatment loss to follow-up, Fiji, 2001–2010

| Variable | Total patients diagnosed n | Patients in TB treatment register n (%) | Pre-treatment loss to follow-up n (%) | OR (95%CI) |

| Age, years | ||||

| <15 | 13 | 13 (100) | 0 | NA |

| ≥15 | 677 | 566 (84) | 111 (16) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 383 | 318 (83) | 65 (17) | Referent |

| Female | 311 | 256 (85) | 46 (15) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) |

| Sex not recorded | 5 | 5 (100) | 0 | NA |

| Geographic division | ||||

| Central | 292 | 267 (91) | 25 (9) | Referent |

| Eastern | 64 | 58 (91) | 6 (9) | 1.1 (0.4–3.0) |

| Western | 205 | 138 (67) | 67 (33) | 5.2 (3.1–8.9)* |

| Northern | 118 | 106 (90) | 12 (10) | 1.2 (0.5–2.6) |

| Others* | 11 | 10 (91) | 1 (9) | NA |

From other Pacific islands.

TB = tuberculosis; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; NA = not available.

DISCUSSION

This first study from the Pacific Islands to assess pre-treatment loss to follow-up rates over a decade shows that about two in 10 individuals with infectious TB were not placed on anti-tuberculosis treatment. The Western Division of Fiji had the highest rates.

The strengths of this study are that we included country-wide data that come from the routine programme setting and are thus likely to reflect the operational reality on the ground, and data were rigorously cross-checked and validated for accuracy. We also adhered to STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines on reporting of observational studies.10

The limitations are that we examined risk of loss to follow-up using a limited number of variables and we did not trace patients to verify whether they had started anti-tuberculosis treatment elsewhere. However, in Fiji, as anti-tuberculosis treatment is only available at centres included in this study, it is unlikely that patients could have accessed care elsewhere. Our results are thus likely to be realistic.

The programme implications of these findings are two fold. First, a considerable proportion of infectious TB cases are not being placed on anti-tuberculosis treatment, and this constitutes a public health risk. Second, cohort reporting of programme outcomes that excludes this group will portray an incorrect picture of programme success, and this is a shortcoming.

We propose a number of ways to correct the current situation. First, the TB laboratory register should include the detailed address and telephone numbers of patients with TB to allow tracing and follow-up. Second, the laboratory and treatment registers should be reconciled on a regular, scheduled basis (e.g., every 2 weeks) to allow early detection of pre-treatment loss to follow-up. To facilitate this process, the laboratory register number should also be entered into the TB patient treatment register and vice versa. Third, quarterly TB reporting should include the number and proportion of pre-treatment loss to follow-up patients. This will allow the NTP to be vigilant and to act in time. Finally, there is a need for specific investigations in the Western Division of Fiji to evaluate the reasons for the higher rates of pre-treatment loss to follow-up here.

In conclusion, this study has identified an important shortcoming in programme linkage, communication and feedback between TB diagnostic and treatment services leading to high pre-treatment loss to follow-up rates. This negatively influences TB services, and urgent steps are being taken to rectify this situation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported through an operational research course that was jointly developed and run by the Centre for Operational Research, International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France, and the Operational Research Unit, Médecins Sans Frontières, Brussels-Luxembourg. Funding for the course was from an anonymous donor and the Department for International Development, London, UK. Additional support for running the course was provided by the Centre for International Health, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Zachariah R, Harries A D, Srinath S, et al. Language in tuberculosis services: can we change to patient-centred terminology and stop the paradigm of blaming the patients? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:714–717. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harries A D, Rusen I D, Chiang C-Y, Hinderaker S G, Enarson D A. Registering initial defaulters and reporting on their treatment outcomes. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:801–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botha E, den Boon S, Lawrence K-A, et al. From suspect to patient: tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment initiation in health facilities in South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:936–941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Botha E, Den Boon S, Verver S, et al. Initial default from tuberculosis treatment: how often does it happen and what are the reasons? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:820–823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buu T N, Lönnroth K, Quy H T. Initial defaulting in the National Tuberculosis Programme in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam: a survey of extent, reasons and alternative actions taken following default. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2003;7:735–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nyirenda T, Harries A D, Banerjee A, Salaniponi F M. Registration and treatment of patients with smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1998;2:944–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sai Babu B, Satyanarayana A V V, Venkateshwaralu G, et al. Initial default among diagnosed sputum smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Andhra Pradesh, India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:1055–1058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Squire S B, Belaye A K, Kashoti A, et al. ‘Lost’ smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis cases: where are they and why did we lose them? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Tuberculosis Control Program. Monitoring and evaluation plan. Suva, Fiji: Fiji Ministry of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elm E V, Altman D G, Egger M, Pocock S J, Gotzche P C, Vandenbroucke J P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Bull World Health Organ. 2007;85:867–872. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.045120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]