Abstract

Background and objective:

In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) published revised dosage recommendations for the treatment of tuberculosis (TB) in children. The aim of the survey was to assess whether countries adopt these new dosage recommendations, as well as to identify challenges in the management and treatment of childhood TB. In addition, countries were asked to provide 2010 surveillance data on childhood TB.

Design:

A survey questionnaire was developed and broadly disseminated to National Tuberculosis Programmes or people with close links to them.

Results:

Among the 34 countries that responded to the survey, the proportion of total national TB caseload reported in children in 2010 ranged from 0.67% to 23.6%. The data on new cases reported to this survey varied from data provided to the WHO global TB database. Most countries had childhood TB guidelines in place, and half had adopted the new dosage recommendations. Countries reported a number of challenges related to the implementation of the new recommendations and general management of childhood TB.

Conclusions:

Despite the adoption of the new dosage recommendations, their implementation is complicated by the lack of appropriate fixed-dose combinations. In addition, accurate and consistent estimates of the global burden of childhood TB remained a major challenge. Technical assistance and support to countries is needed to improve childhood TB activities.

Keywords: childhood TB, disease burden, anti-tuberculosis medicines, guidelines

Abstract

Contexte et objectif:

En 2010, l’Organisation Mondiale de la Santé (OMS) a publié des recommandations concernant la révision du dosage pour le traitement de la tuberculose (TB) infantile. Le but de cette enquête a été d’évaluer dans quelle mesure les pays ont adopté ces nouvelles recommandations concernant le nouveau dosage des médicaments et identifié les défis dans la prise en charge et le traitement de la TB infantile. En outre, on a demandé aux pays de fournir les données de surveillance de la TB infantile en 2010.

Schéma:

Un questionnaire d’enquête a été élaboré et disséminé largement aux Programmes Nationaux de Tuberculose (PNT) et aux personnes très proches des PNT.

Résultats:

Parmi les 34 pays qui ont répondu à l’enquête, la proportion du fardeau total national des cas de TB rapportée en 2010 chez les enfants s’est étalée entre 0,67% à 23,6%. Les données concernant les nouveaux cas relatés dans cette enquête ont été différentes de celles fournies à la base mondiale de données de la TB de l’OMS. La plupart des pays disposaient de recommandations pour la TB infantile, et la moitié avaient adopté les recommandations concernant le nouveau dosage. Des pays ont signalé un certain nombre de défis en relation avec la mise en œuvre des nouvelles recommandations et la prise en charge générale de la TB infantile.

Conclusions:

Malgré l’adoption des recommandations concernant le nouveau dosage, leur mise en œuvre est compliquée par le manque de combinaisons à dose fixe appropriée. De plus, des estimations exactes et cohérentes du fardeau mondial de la TB infantile restent un défi important. Une aide et un soutien techniques aux pays sont nécessaires afin d’améliorer les activités en matière de TB infantile.

Abstract

Marco de referencia y objetivo:

En el 2010, la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS) publicó una revisión de las pautas posológicas recomendadas en el tratamiento de la tuberculosis (TB) en los niños. El objetivo del presente estudio fue evaluar el grado de adopción de estas nuevas recomendaciones por parte de los países y determinar los obstáculos que se presentan en el manejo y el tratamiento de este tipo de TB. Asimismo, se solicitó a los países que suministraran los datos de vigilancia de la TB de los niños en el 2010.

Método:

Se elaboró el cuestionario de la encuesta y se difundió ampliamente a los Programas Nacionales de control de la Tuberculosis o a las personas que sostienen un vínculo estrecho con estos programas.

Resultados:

Treinta y cuatro países respondieron a la encuesta. La proporción de la carga de morbilidad total por TB que correspondió a los niños en el 2010 osciló entre 0,67% y 23,6%. Los datos sobre los casos nuevos notificados en esta encuesta difirieron de los datos su-ministrados a la base mundial de datos sobre la TB de la OMS. La mayoría de los países cuentan localmente con directrices en materia de TB de los niños y la mitad de ellos han adoptado las nuevas pautas posológicas recomendadas. Los países notificaron una serie de obstáculos relacionados con la puesta en práctica de las nuevas recomendaciones y con el manejo general de la TB de los niños.

Conclusión:

Pese a la adopción de las recomendaciones sobre las nuevas posologías, su puesta en práctica se dificulta debido a la falta de combinaciones de dosis fijas adecuadas. Además, lograr un cálculo preciso y sistemático de la carga de morbilidad mundial por TB en los niños constituye aun un obstáculo importante. Los países precisan asistencia técnica y apoyo con el fin de mejorar las actividades relacionadas con la TB en la infancia.

In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) published a Rapid Advice document with updated dosage recommendations for anti-tuberculosis (TB) medicines in children.1 Dosages for isoniazid (H, INH), rifampicin (R, RMP) and pyrazinamide (Z, PZA) were increased compared to the dosages recommended in the ‘Guidance for national tuberculosis programmes on the management of tuberculosis in children’, published by the WHO in 2006.2 The recommendations for the dosage of ethambutol (E, EMB) in young children had already been updated in 2006 (Table 1).3 The changes were informed by pharmacokinetic data consistently showing that dosages recommended for adults do not reach adequate levels in infants and young children. A recent pharmacokinetic study in children aged <2 years reported higher levels with the revised dosages compared to the previously recommended dosages.4 Importantly, the increased dosages do not increase the risk of hepatotoxicity.5

TABLE 1.

WHO dosage recommendations, 2006 and 2010

| WHO 20062* | WHO 20101 | |

| Isoniazid, mg/kg | 5 (4–6)† max 300 mg/day | 10 (10–15) max 300 mg/day |

| Rifampicin, mg/kg | 10 (8–12) | 15 (10–20) max 600 mg/day |

| Pyrazinamide, mg/kg | 25 (20–30) | 35 (30–40) |

| Ethambutol, mg/kg | 20 (15–25) | 20 (15–25) |

Recommendations for daily treatment. Slightly different dosages are recommended for intermittent therapy (thrice weekly).

For treatment of both Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and active tuberculosis.

WHO = World Health Organization.

There are currently no fixed-dose combinations (FDCs) available to match these new dosage recommendations. Interim recommendations, combining existing FDCs with single formulations, were therefore provided by the WHO and the Global Drug Facility (GDF) for dosing in different weight bands (excluding children <5 kg; http://www.who.int/tb/challenges/interim_paediatric_fdc_dosing_instructions_sept09.pdf). However, adoption of these interim recommendations may prove challenging at country level in the procurement of medicines and provision of correct dosages for children with TB.

An informal consultation on missing priority medicines for children at the WHO headquarters in Geneva in July 2011 discussed strategies to advance the availability of an FDC for childhood TB. The need for a survey on the adoption and implementation of the new dosage recommendations, procurement mechanisms and challenges with regard to provision of anti-tuberculosis treatment for children was identified, which was the aim of this study. In addition, we aimed to determine the burden of childhood TB in the participating countries.

METHODS

The present survey was performed between December 2011 and February 2012 by the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union) and the Childhood TB subgroup of the DOTS Expansion Working Group of the Stop TB Partnership.

A questionnaire was developed to collect national data on 1) guidelines on the management of childhood TB, 2) dosage recommendations for first-line childhood TB medicines, 3) implementation of the new recommendations and 4) funding and procurement mechanisms for childhood TB medicines. In addition, we asked the countries to report their surveillance data for 2010 to obtain an estimate of the childhood TB burden. Open questions were asked of participants to describe the challenges related to the management of childhood TB.

The questionnaire was made available in English, French and Spanish, and was distributed broadly via the WHO to National TB Programme (NTP) staff during the African, South-East Asian, European and Eastern Mediterranean regional meetings, as well as via The Union and direct country contacts.

RESULTS

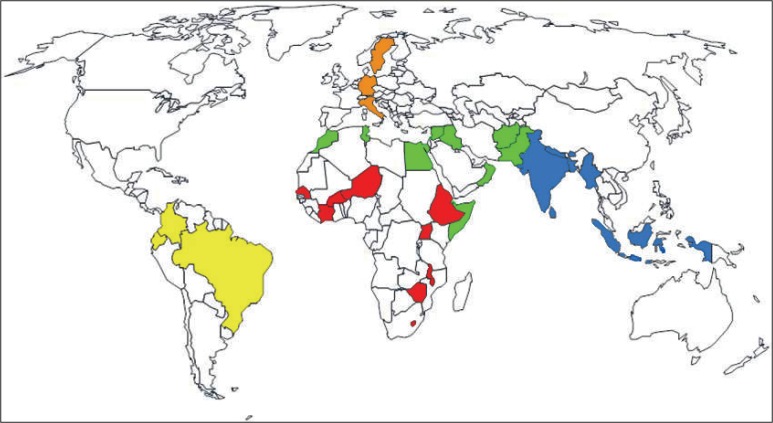

By February 2012, 34 countries from five regions (Africa, the Americas, Eastern Mediterranean, Europe and South-East Asia) had responded to the survey (Figure). Table 2 shows an overview of those countries, their TB burden (WHO 2010) and World Bank income status (http://wdronline.worldbank.org/worldbank/a/region, 2010). Ten countries were among the 22 TB high-burden countries, 4 were high-income, 5 upper-middle income, 14 lower-middle income and 11 low-income countries. Twenty-one countries provided contact information for a designated childhood TB focal point.

FIGURE.

Overview of countries participating in the survey by World Health Organization Region: Red: AFRO (Africa), 9 countries; yellow: AMRO (Americas), 3 countries; green: EMRO (Eastern Mediterranean), 11 countries; orange: EURO (Europe), 3 countries; blue: SEARO (South-East Asia), 8 countries. No participation from countries from WPRO (Western Pacific).

TABLE 2.

Overview of countries participating in the survey and information on TB burden and income status

| TB burden | Income status (World Bank, 2010) | 2010 |

|||||

| TB incidence/100 000 (WHO) | New childhood TB cases reported to the WHO* | New childhood TB cases reported through the survey* | Retreatment cases in children reported through the survey | Child TB cases (new and retreatment) of all cases notified %† | |||

| Afghanistan | HBC | LIC | 189 (155–226) | 642 | 2 946 | No data | 10.43 |

| Bangladesh | HBC | LIC | 225 (184–269) | 4 235 | 4 235 | No data | 2.67 |

| Bhutan | LMIC | 151 (127–177) | 17 | 12 | No data | 0.90 | |

| Brazil | HBC | UMIC | 43 (36–51) | 2 450 | 548 | No data | 0.67 |

| Burkina Faso | LIC | 55 (46–64) | 53 | 128 | No data | 2.49 | |

| Colombia | UMIC | 34 (28–41) | 719 | 755 | 23 | 6.54 | |

| Côte D’Ivoire | LMIC | 139 (120–160) | 405 | 1 116 | No data | 4.81 | |

| Djibouti | LMIC | 620 (510–741) | 48 | 38 | No data | 0.91 | |

| Ecuador | UMIC | 65 (53–78) | 84 | No data | No data | 1.65‡ | |

| Egypt | LMIC | 18 (15–21) | 490 | 490 | No data | 5.11 | |

| Ethiopia | HBC | LIC | 261 (240–282) | 3 190 | 17 566 | No data | 11.19 |

| Germany | HIC | 4.8 (4.2–5.4) | 150 | 158 | 31 | 3.65 | |

| India | HBC | LMIC | 185 (167–205) | 13 415 | 85 756 | 4434 | 5.93 |

| Indonesia | HBC | LMIC | 189 (155–226) | 28 312 | 28 312 | 42 | 9.36 |

| Iraq | LMIC | 64 (52–77) | 691 | 691 | 23 | 7.07 | |

| Italy | HIC | 4.9 (4.3–5.5) | 122 | 121 | 0 | 3.72 | |

| Lebanon | UMIC | 17 (15–20) | 43 | 43 | 0 | 8.35 | |

| Lesotho | LMIC | 633 (551–721) | 707 | 707 | No data | 5.46 | |

| Malawi | LIC | 219 (203–237) | 153 | 153 | No data | 0.68 | |

| Morocco | LMIC | 91 (80–104) | 2 159 | 1 783 | 51 | 6.37 | |

| Myanmar | HBC | LIC | 384 (328–445) | 302 | 32 471 | No data | 23.63 |

| Nepal | LIC | 163 (134–195) | 357 | 330 | No data | 0.93 | |

| Niger | LIC | 185 (152–221) | 83 | 585 | No data | 5.65 | |

| Oman | HIC | 13 (12–15) | 14 | 9 | 0 | 2.88 | |

| Pakistan | HBC | LMIC | 231 (189–277) | 24 474 | 24 474 | No data | 9.09 |

| Senegal | LMIC | 288 (237–345) | 162 | 585 | No data | 5.05 | |

| Somalia | LIC | 286 (235–342) | 200 | 2 216 | No data | 21.17 | |

| Sri Lanka | LMIC | 66 (54–79) | 392 | 392 | No data | 3.88 | |

| Sweden | HIC | 6.8 (5.9–7.7) | 37 | 44 | 3 | 6.96 | |

| Syria | LMIC | 20 (16–24) | 421 | 421 | 0 | 11.00 | |

| Timor Leste | LMIC | 498 (407–598) | No data | 284 | No data | No data available | |

| Tunisia | HBC | UMIC | 25 (22–28) | 13 | 158 | 0 | 6.67 |

| Uganda | HBC | LIC | 209 (168–254) | 669 | 662 | No data | 1.45 |

| Zimbabwe | LIC | 633 (486–799) | 4 371 | 4 383 | 213 | 9.66 | |

Data requested for new cases: smear-positive, smear-negative and extra-pulmonary TB, 0–14 years as well as disaggregated (0–4 and 5–14 years).

Calculated using childhood TB data provided to the survey rather than WHO data.

Ecuador: No childhood TB data provided in the survey; data used from WHO 2010 database.

TB = tuberculosis; WHO = World Health Organization; HBC = high-burden country; LIC = low-income country; LMIC = lower middle-income country; UMIC = upper middle-income country; HIC = high-income country.

Childhood tuberculosis burden 2010

The proportion of total national TB caseload that occurred in children (0–14 years) in 2010 ranged from 0.67% to 23.6%, including smear-positive, smear-negative, extra-pulmonary TB and retreatment cases and using data provided in the survey (Table 2). In actual numbers, this represented from 9 to 90 190 cases of childhood TB registered with the NTPs of the listed countries in 2010. As one country did not report childhood TB data from 2010 in the survey, data from the WHO database was used instead to calculate the burden (http://www.who.int/tb/country/data/profiles/en/index.html).

Not all countries reported their cases in the different disease categories: 32 countries reported only smear-positive cases, 24 included smear-negative cases, and 24 included extra-pulmonary cases (Table 3). For 19 countries, discrepancies were noted between the case numbers received for the survey and childhood TB data in the WHO database, with more cases being reported to the survey than to the WHO by 14 countries (Table 2).

TABLE 3.

TB data 2010. Number of countries surveyed that reported the different case categories as well as disaggregation into age groups 0–4 and 5–15 years

| Total | Disaggregated | |

| New pulmonary smear-positive | 32 | 21 |

| New pulmonary smear-negative | 24 | 19 |

| Extra-pulmonary | 24 | 18 |

| Retreatment | 13 | 10 |

TB = tuberculosis.

In addition to data on new cases, 13 countries were able to provide data on retreatment among children, although these data are not routinely collected through the WHO global TB data collection system (Table 2).

Eighteen countries (50%) reported disaggregated data for total cases of TB in children aged 0–4 and 5–14 years.

Childhood tuberculosis guidelines

Twenty-nine countries reported having childhood TB guidelines in place, 20 of which had been updated since the end of 2009. Eighteen countries indicated incorporation of the new WHO dosage recommendations into the national guidelines. In addition, 22 countries had adapted the WHO 2006 childhood TB guidance and 8 the 2010 WHO/The Union TB/HIV guidance for children to the local context.1,2,6

Twenty-seven countries defined a child as age 0–14 years, sometimes in combination with a weight cut-off of 30–35 kg (4 countries). The remainder used either weight or different age cut-offs.

Provision of preventive therapy

Thirty countries specified the provision of INH preventive therapy (IPT; 5–15 mg/kg) for 6 months and some up to 12 months in their guidelines. Eleven countries recommended 5 mg/kg, fourteen 10 mg/kg, four 5–10 mg/kg and one 10–15 mg/kg.

Of 17 countries that indicated having included the 2010 Rapid Advice with increased dosage recommendations in their childhood TB guidelines, four still recommended 5 mg/kg INH for preventive therapy, two 5–10 mg, ten 10 mg and two gave no indication.

Three countries recommended INH and RMP for 3 months as preventive therapy: Sweden and Germany as an alternative to 9 months of INH, and Niger as sole preventive treatment.

Recommendations for childhood tuberculosis medicines and the implementation of increased dosage recommendations

This survey focused on the management of drug-susceptible TB. In the majority of countries, the recommended regimen for the treatment of new cases of childhood TB (smear-positive and -negative) was HRZ for 2 months (plus E in complicated cases or adult-type disease) followed by HR for 4 months. Some countries added E only for children aged >10 years or >20 kg bodyweight.

The recommended dosages for childhood TB medicines were applied according to WHO 2006 guidance in 12 countries and according to the 2010 Rapid Advice in 19 countries, with some making modifications to individual drugs (Table 4). Some countries had taken the WHO new recommendations into account but adapted the dosages in their national guidelines: Germany had adjusted its dosage recommendations to body surface area or mg/kg bodyweight for different age groups, reaching lower levels than recommended by the WHO (such as for INH in older children), while Italy gave a dose-range. India provided intermittent therapy thrice weekly, which was still recommended as an alternative to daily treatment by the WHO in 2006, but not in the 2010 Rapid Advice.

TABLE 4.

Overview of countries’ guidelines and implementation status regarding ‘old’ versus ‘new’ WHO dosage recommendations

| Country | Guidelines include 2010 Rapid Advice | Dosage recommendations for childhood TB (guidelines) | Imple-mentation of Rapid Advice started? | Imple-mentation planned? |

| Afghanistan | WHO 2006 | Yes | ||

| Bangladesh | Yes | WHO 2010 | Yes | |

| Bhutan | Yes | WHO 2010 | Yes | |

| Brazil | WHO 2010 | Yes* | ||

| Burkina Faso | Yes | WHO 2010 | Yes | |

| Colombia | Yes | WHO 2010 | Yes | |

| Côte D’Ivoire | WHO 2006 | No | ||

| Djibouti | Yes | WHO 2006 | No | Yes |

| Ecuador | WHO 2006 | No | Yes | |

| Egypt | WHO 2006 | No | Yes | |

| Ethiopia | Yes | WHO 2010 | Yes | |

| Germany | Yes | Age- or body surface area-adjusted dosages | No† | No comment |

| India | Thrice-weekly intermittent | No | No with exception‡ | |

| Indonesia | Yes | WHO 2010 (adapted)§ | Yes | |

| Iraq | Yes | WHO 2006 | No | Yes |

| Italy | Dose-range | No | No comment | |

| Lebanon | WHO 2006¶ | No | No comment | |

| Lesotho | WHO 2010 | No | Yes | |

| Malawi | Yes | WHO 2006 | No | Yes |

| Morocco | Yes | WHO 2010 | Yes | |

| Myanmar | WHO 2006 | Yes | ||

| Nepal | Yes | WHO 2010 | Yes | |

| Niger | Yes | WHO 2010 | Yes | |

| Oman | Yes | WHO 2010 | Yes | |

| Pakistan | Yes | WHO 2010 | Yes | |

| Senegal | Yes | WHO 2010 | No | Yes |

| Somalia | WHO 2006 | No | Yes | |

| Sri Lanka | WHO 2006 | No | No | |

| Sweden | WHO 2010 | Yes | ||

| Syria | WHO 2010 modified# | Yes | ||

| Timor Leste | WHO 2006 modified** | No | Yes | |

| Tunisia | Yes | WHO 2010 | No | Yes |

| Uganda | Yes | WHO 2010 | No | No comment |

| Zimbabwe | Yes | WHO 2010 | Yes |

Brazil: dose-range recommended for R (10–20 mg).

Germany: adjusted dosage recommendations, partly reaching levels recommended in Rapid Advice, were already in place.

India: dosages for intermittent therapy will be increased and daily therapy introduced during the intensive phase for seriously ill children while admitted to hospital (http://tbcindia.nic.in/Paediatric%20guidelines_New.pdf).

Indonesia: lower dosage recommendation for Z (15–30 mg) and E (15–20 mg).

Guidelines according to WHO 2006, but most dosages recommended and prescribed by private paediatricians.

Syria: lower dosage recommendation for Z (25 mg/kg).

Timor Leste: lower dosage recommendation for E (15 mg/kg).

WHO = World Health Organization; TB = tuberculosis; R = rifampicin; Z = pyrazinamide; E = ethambutol.

When asked about implementation of the new dosage recommendations, 16/34 (47%) countries indicated that they had started implementation. However, these 16 countries did not completely overlap with those countries that indicated that their dosage recommendations had been updated to include the 2010 Rapid Advice: three indicated dosage recommendations that were still in line with WHO 2006 guidelines (Table 4).

Eleven countries were planning to implement the new dosage recommendations in the near future, and four did not comment on implementation plans. Three countries had decided not to implement the new dosage recommendations yet: Sri Lanka because the consulting physicians were not convinced of the added benefit since the old regimen seemed to give satisfactory results; Côte D’Ivoire did not give a reason; and India had recently decided to increase dosages recommended for intermittent therapy and to provide daily therapy for seriously ill, hospitalised children during the intensive phase of treatment.7

To deliver correct dosages to children, 11 countries were using adult formulations, which were either broken or crushed, 11 were combining existing FDCs and loose products, while 2 countries were using only loose products.

Obstacles to the implementation of the new dosage recommendations were related to delays in updating existing guidelines, training of health care staff at all levels, the unavailability of FDCs to match the new recommendations (causing some countries to delay implementation until formulations were available) as well as the quality of medicines, procurement politics and delays in drug delivery.

Funding and procurement

Ten countries used only government budgets to fund childhood TB medicines. Seventeen used grants from the GDF, four used UNITAID grants, and ten used grants from the Global Fund. There was partial overlap, with different funding sources, including government funding, being used in the same country. Other mechanisms included hospital budgets (n = 1) or coverage through health insurance (n = 1).

Most countries (n = 21) used the GDF as the main mechanism for the purchase of medicines, while 14 used national procurement systems as the sole or an additional mechanism. Two Latin American countries indicated purchase through the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO).

Both existing FDCs and loose medicines for children were purchased by the countries, mostly RHZ 60/30/150 and INH 100 (Table 5). Two countries, India and Indonesia, were providing locally manufactured prepacked combinations of medicines.

TABLE 5.

Number of countries purchasing different formulations of anti-tuberculosis medicines

| Formulation | Countries n |

| RHZ 60/30/150 | 24 |

| RH 60/60 | 6 |

| RH 60/30 | 18 |

| RH 150/75 | 4 |

| RH 300/150 | 2 |

| RHZE 150/75/400/275 | 7 |

| R 100 mg/5 ml susp. | 9 |

| H 100 | 21 |

| H 300 | 3 |

| Z 100 | 1 |

| Z 500 | 9 |

| E 100 | 12 |

| E 400 | 11 |

| S 1000 (1g) | 13 |

| Other | India: paediatric patient wise boxes* Indonesia: combipacs R 450, H 300, Z 500, E 250 or R 450, H 300† |

Medicines were provided in patient-wise boxes, mainly by local manufacturers, per the requirements of the Indian RNTCP.

Combipacks were produced by state manufacturers using the government budget, while the Global Fund allocation for paediatric TB remains unabsorbed. In 2012, the state manufacturer started producing paediatric FDCs matching the new dosage recommendations.

R = rifampicin; H = isoniazid; Z = pyrazinamide; E = ethambutol; S = streptomycin; RNTCP = Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme.

Challenges and needs in implementation

Finally, countries were asked to highlight challenges in the management of childhood TB and implementation of treatment, particularly related to 1) the availability of drugs for treatment of disease or preventive therapy, 2) the delivery of medicines to children, 3) matching of dosage recommendations with medicines that were available, and 4) adherence to treatment.

The following challenges and needs were noted:

-

General challenges in diagnosis and management of child-hood TB

Implementation of NTP guidelines, training and awareness of health care staff at all levels

Need for training of trainers through international bodies

Lack of better diagnostics for childhood TB

Over- and underdiagnosis of childhood TB

Recording and reporting tools not suitable for childhood TB, e.g., they did not include treatment outcomes for children.

-

Feasibility of treatment

Need for child-friendly formulations (such as suspensions) for both treatment of disease and preventive therapy to make delivery more feasible

FDCs necessary to improve treatment outcomes

Poor adherence rates, which may be explained by the lack of child-friendly formulations

Challenges in matching the new recommendations with available medicines

Challenges for parents to comply with complicated dosing instructions (combining FDCs with individual drugs, the need to crush some drugs, etc), which may lead to problems in adherence

Crushing adult tablets may lead to over-/underdosing

Challenges in monitoring the side effects of anti-tuberculosis treatment in children

Increases in the quantity of pills with new recommendations

Matching dosages at the cut-offs for weight bands (over-/ underdosing).

-

Drug procurement

Availability of paediatric formulations (in general, but also coverage within countries)

Delays in shipments and drug stock-outs

Procurement through local markets in the case of shipment delays was difficult

Correct calculation of quantity of medicines. Underdiagnosis of childhood TB can lead to expiry of medicines on the shelves.

-

Preventive therapy

IPT not implemented despite being included in childhood TB guidelines

Reluctance of parents to give chemoprophylaxis to healthy children

Need for better information systems and reporting of IPT

Shortages and stock-outs of INH 100 for IPT.

DISCUSSION

This survey was aimed at NTPs who routinely report surveillance data on childhood TB to the WHO. An unexpected finding was the sometimes wide discrepancies between the 2010 childhood TB surveillance data submitted to the WHO and the data received for the survey. This can partly be explained by the fact that only data on new smear-positive cases were submitted to the WHO despite the option of reporting smear-negative and extra-pulmonary TB cases. For example, one country reported over 13 000 childhood TB cases (only new sputum smear-positive) to the WHO in 2010, but over 85 000 cases to the survey, including smear-negative and extra-pulmonary TB cases. The need for improved recording and reporting of childhood TB is further highlighted by the example of Malawi where, counting only smear-positive cases, children contributed less than 1% to the total caseload in 2010, while a national survey reported that all TB cases treated in one year in Malawi, including smear-negative and extra-pulmonary TB, accounted for almost 12% of the total TB burden.8 Improved estimates for childhood TB will facilitate advocacy efforts, attract manufacturers of TB medicines by showing a larger market, and almost certainly increase funding for childhood TB.

Almost all countries had updated childhood TB guidelines that included the treatment of active disease as well as preventive therapy. Recommendations for both dosage and duration of IPT varied across countries. It should be noted that the Rapid Advice focuses on anti-tuberculosis treatment and does not mention whether increased dosages should also be used for preventive therapy. However, a recommendation to use 10 mg/kg INH for IPT had been included in more recent guidelines by both the WHO and The Union.6,9 The WHO is currently revising a comprehensive childhood TB guidance that will incorporate all new recommendations currently spread among several policy documents and guidelines.

The survey did not attempt to assess the general implementation status of childhood TB activities at country level, which is known to be challenging due to various factors such as lack of training, resources and suitable diagnostics for children.10

When asked about implementation of the new dosage recommendations, 16 countries had started and 11 planned to implement them in the future, using adult formulations or combinations of existing FDCs and loose products to match the dosages in the absence of new FDCs. It was, however, difficult to obtain a clear picture of the real stage of roll-out at country level.

The countries did note a large number of obstacles and challenges related to the implementation of childhood TB treatment. Besides general challenges such as implementation of guidelines, training of staff and lack of better diagnostics for childhood TB, the majority of the challenges highlighted were related to the feasibility of treatment given the lack of child-friendly formulations and new FDCs adjusted to the new dosage recommendations. Combining adult formulations and loose products is complex and difficult for all sides involved: the NTP has to ensure that there are enough stocks to match the different recommendations for different weight bands, health workers have to calculate and provide correct combinations to the parents, who then have to learn how to deliver the medicines to their children, sometimes crushing adult drugs and mixing them with paediatric drugs, all of which can lead to dosing errors. This can only be a short-term solution.

The recognition of these challenges and the difficulties in implementing the revised dosages has led to various steps being taken by the WHO in 2012: new FDCs for HRZ and HR with an H:R ratio of 2:3 were included in the Invitation for Expression of Interest (EoI) for product evaluation to the WHO Prequalification Programme, removing one barrier for manufacturers who wish to engage in the process of manufacturing these new FDCs. Continuous guidance and technical assistance for manufacturers is necessary given the mandatory proof of efficacy, safety and stability they will have to provide to demonstrate that their FDCs are quality assured. The new FDC will facilitate treatment administration, with no need for an additional INH tablet to be added to com-ply with recent changes to dosage recommendations. In addition, the current recommended range of INH (10–15 mg/kg) is under review, considering new evidence and the influence of age and acetylator status on INH pharmacokinetics.4,11 A wider range would facilitate the use of currently available FDCs as well as the new FDC that has been approved.

Most countries use the GDF to procure medicines for childhood TB, which assures the quality of the drugs provided. However, GDF is challenged by the availability of only a limited number of child-friendly formulations and a relatively small market providing existing FDCs, which are insufficient to match the new dosage recommendations.12 To create a market and attract pharmaceutical companies to engage in child-friendly anti-tuberculosis medicines, the estimates on childhood TB must be improved at national as well as global level. Recent estimates in the Global Tuberculosis Report 2012 by WHO indicate that at least half a million new cases of childhood TB occur every year.13,14 Data reported to this survey, however, suggest that the caseload in many countries is actually higher than reported to the WHO. In addition, due to the challenges related to the management of childhood TB expressed by the countries surveyed, it is expected that a large number of children with TB remain under-diagnosed or under-reported.

There is a clear need for better support for NTPs to implement existing policies through training and technical assistance, ensuring that all children with active TB or needing preventive therapy are identified. Most urgently, the availability of child-friendly medicines and more suitable FDCs would greatly improve the management of and outcomes for children with TB.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of the childhood TB subgroup of the DOTS Expansion Working Group of the Stop TB Partnership who provided input to the survey questionnaire (A Hesseling, H Menzies, L Obimbo, H S Schaaf). They appreciate the support of many WHO and Union country staff who helped to disseminate and fill out the survey. Above all, they thank all countries who participated and the people who dedicated time to fill out the survey: S D Mahmoodi, V Begum, S Yangchen, C C Sant’Anna, S P Diabouga, E Moreno, M C Barouan, R Jebeniani, V M Carrillo, A Mokhtar, B Kebede, B Hauer, A Kumar, D E Mustikawati, M Yahya, E M Ruga, H Yaacoub, L Maama, H Kanyerere, K Bennani, T Lwin, M Akhtar, B Ballé, M R M Al Lawati, I Fatima, A H Diop, I A Abdilahi, S Samara, R Bennet, K Cheikh, D Pereira, D Gamara, I Joseph, T Murimwa. Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2010. Rapid Advice: treatment of tuberculosis in children. WHO/HTM/TB/2010.13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2006. Guidance for national tuberculosis programmes on the management of tuberculosis in children. WHO/HTM/TB/2006.371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2006. Ethambutol efficacy and toxicity: literature review and recommendations for daily and intermittent dosage in children. WHO/HTM/TB/2006.365. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thee S, Seddon JA, Donald PR, et al. Pharmacokinetics of isoniazid, rifampicin and pyrazinamide in children younger than two years of age with tuberculosis; evidence for implementation of revised World Health Organization Recommendations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:5560–5567. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05429-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donald PR. Antituberculosis drug-induced hepatotoxicity in children. Pediatr Rep. 2011;3:e16. doi: 10.4081/pr.2011.e16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization/International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease . Paris, France: The Union; 2010. Guidance for national tuberculosis and HIV programmes on the management of tuberculosis in HIV-infected children: recommendations for a public health approach. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuberculosis Control India . New Delhi, India: TBC India, Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2012. National guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of pediatric tuberculosis. http://tbcindia.nic.in/Paediatric%20guidelines_New.pdf Accessed November 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harries AD, Hargreaves NJ, Graham SM, et al. Childhood tuberculosis in Malawi: nationwide case-finding and treatment outcomes. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6:424–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2011. Guidelines for intensified tuberculosis case finding and isoniazid preventive therapy for people living with HIV in resource-constrained settings. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hill PC, Rutherford ME, Audas R, van Crevel R, Graham SM. Closing the policy-practice gap in the management of child contacts of tuberculosis cases in developing countries. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001105. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schaaf HS, Parkin DP, Seifart HI, et al. Isoniazid pharmacokinetics in children treated for respiratory tuberculosis. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:614–618. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.052175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gie RP, Matiru RH. Supplying quality-assured child-friendly anti-tuberculosis drugs to children. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:277–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stop TB Partnership, World Health Organization Stop TB Department. No more crying no more dying . Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2012. Towards zero TB deaths in children. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization . Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2012. Global tuberculosis report 2012. WHO/HTM/TB/2012.6. [Google Scholar]