Abstract

Setting:

Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital, Blantyre, Malawi.

Objectives:

To determine 1) the proportion of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected tuberculosis (TB) patients started on antiretroviral therapy (ART), 2) the timing of ART and 3) the effect of the timing on TB treatment outcomes.

Design:

A retrospective record review of HIV-infected TB patients registered from January to December 2009.

Results:

A total of 3376 TB patients were registered, of whom 2665 (79%) were HIV-tested and 2042 (77%) were HIV-infected. A total of 1190 HIV-infected TB patients who were not on ART at the time of starting TB treatment were studied. Of 688 (58%) who started ART, 61% started therapy within 2 months of anti-tuberculosis treatment and 39% started later (≥2 months). Treatment success for patients with TB who started ART within 2 months was higher than for those starting ART later (RR 1.6, 95%CI 1.4–1.8), and death rates were lower (RR 0.25, 95%CI 0.19–0.35).

Conclusion:

Under routine programme conditions in Malawi, a higher proportion of HIV-infected TB patients who started ART did so within 2 months of starting TB treatment, and early ART intervention was associated with better treatment outcomes. This confirms recommendations that co-infected TB patients should start ART early.

Keywords: tuberculosis, timing, operational research, Malawi

Abstract

Contexte:

Hôpital Central Reine Elisabeth, Blantyre, Malawi.

Objectifs:

1) Déterminer la proportion de patients tuberculeux infectés par le virus de l’immunodéficience humaine (VIH) mis sous traitement antirétroviral (ART), 2) le moment du début de l’ART et 3) l’effet du moment du début de l’ART sur les résultats du traitement antituberculeux.

Schéma:

Revue rétrospective des dossiers des patients tuberculeux infectés par le VIH, enregistrés entre janvier et décembre 2009.

Résultats:

Au total, 3376 patients ont été enregistrés, parmi lesquels 2665 (79%) ont été testés pour le VIH et 2042 (77%) étaient infectés par le VIH. On a étudié 1.190 patients TB infectés par le VIH qui n’étaient pas sous ART au moment du début du traitement de la TB ; 688 (58%) d’entre eux ont commencé l’ART et parmi ceux-ci, 61% ont commencé le traitement dans les 2 premiers mois du traitement anti-tuberculose et 39% ont commencé plus tard (≥2 mois). Le succès du traitement chez les patients TB mis sous ART au cours des 2 premiers mois a été plus fréquent que chez ceux où l’ART a débuté plus tard (RR 1,6 ; IC95% 1,4–1,8), et d’autre part les taux de décès ont été plus bas dans les traitements précoces (RR 0,25 ; IC95% 0,19–0,35) que dans les traitements plus tardifs.

Conclusion:

Dans les conditions de routine du programme au Malawi, une proportion plus élevée de patients tuberculeux infectés par le VIH qui ont commencé l’ART l’ont fait au cours des 2 premiers mois du début de traitement de la TB, et les interventions ART précoces sont en association avec de meilleurs résultats du traitement. Ceci confirme les recommandations selon lesquelles les patients TB co-infectés devraient commence précocement l’ART.

Abstract

Marco de referencia:

El hospital Queen Elizabeth Central de Blantyre, en Malawi.

Objetivos:

1) Determinar la proporción de pacientes con tuberculosis (TB) coinfectados por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH) que comenzaban el tratamiento antirretrovírico (ART); 2) registrar el momento del comienzo de este tratamiento; y 3) analizar el efecto de la simultaneidad de ambos tratamientos sobre el desenlace clínico de la TB.

Método:

Se llevó a cabo un estudio retrospectivo de las historias clínicas de los pacientes tuberculosos coinfectados por el VIH entre enero y diciembre del 2009.

Resultados:

Durante el período del estudio se registraron 3376 pacientes con TB y en 2665 de ellos (79%) se practicó la prueba serológica del VIH cuyo resultado fue positivo en 2042 casos (77%). Se estudiaron 1190 pacientes TB coinfectados por el VIH que aun no recibían ART al iniciar el tratamiento antituberculoso. Comenzaron ART 688 pacientes (58%), el 61% en los 2 primeros meses del tratamiento antituberculoso y el 39% lo comenzó más tarde (≥2 meses). El desenlace terapéutico de los pacientes tuberculosos que comenzaron el ART durante los 2 primeros meses fue más favorable que el desenlace de los pacientes que lo comenzaron más tarde (RR 1,6; IC95% 1,4–1,8) y presentaron una tasa de mortalidad más baja (RR 0,25; IC95% 0,19–0,35).

Conclusión:

En las condiciones corrientes del programa de Malawi, una mayor proporción de pacientes TB coinfectados por el VIH empezó a recibir ART en los primeros 2 meses de iniciado el tratamiento antituberculoso y esta intervención se asoció con un desenlace terapéutico más favorable. Este resultado respalda la recomendación de comenzar el ART de manera temprana en los pacientes que padecen además de TB.

Tuberculosis (TB) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are major public health problems in many sub-Saharan African countries.1 Malawi is severely affected by the dual epidemics of HIV and TB. Annual TB case notifications increased from 5000 in 1985 to over 23 000 in 2011. This has had a negative impact on the well-functioning Malawi National TB Programme (NTP) as well as on the staff involved.2 In addition, HIV prevalence among TB patients of 64% in 20113 resulted in high case-fatality rates and low treatment success rates.

In 2004, the country embarked on rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy (ART),4,5 resulting in nearly 300 000 patients recorded as alive and on ART by the end of 2011.6 While there is good progress in providing ART, only 45% of eligible TB patients co-infected with HIV were accessing ART in 2009 under routine programme conditions in Malawi. This is in contrast to the 96% on cotrimoxazole preventive therapy (CPT) in Malawi,7 and in contrast to reports of better ART uptake among HIV-infected TB patients in Kenya of 70%.8

The 2008 Malawi ART guidelines stated that all HIV-infected TB patients were eligible for ART, but recommended that ART should start in general after the initial phase of anti-tuberculosis treatment unless the patient was sick, in which case treatment should be started earlier.9 Since then, evidence from randomised controlled trials (CAMELIA, STRIDE and SAPIT)10–12 has clearly shown that ART should be started during the initial phase of anti-tuberculosis treatment, and preferably within the first 2–4 weeks of the start of anti-tuberculosis treatment. The 2010 World Health Organization (WHO) ART guidelines now explicitly recommend that ART should be started as early as possible,13 and in the Malawi 2011 ART guidelines this is the new recommendation.

Malawi has well-functioning TB and HIV programmes and provides well-monitored HIV and TB services. We therefore decided to assess the effect of ART and timing of therapy in HIV-infected TB patients within the programme setting. The objectives of our study were to determine 1) the proportion of HIV-infected TB patients started on ART, 2) the timing of ART and 3) the effect of the timing of ART on TB treatment outcomes.

METHODS

Study design

This was a retrospective cohort study involving a record review of HIV-infected TB patients registered from 1 January to 31 December 2009.

Setting

The study was conducted at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital (QECH) in Blantyre District, Malawi, in October and November 2011. QECH is a tertiary hospital, and also serves as a district hospital to Blantyre District. Despite its being a tertiary hospital, TB and ART services are similar to those of any other hospital in the country. At registration, TB patients are started on anti-tuberculosis treatment and receive counselling and testing for HIV (opt-out provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling); if the patient is HIV-infected, CPT is started immediately.

QECH follows the recommended WHO DOTS strategy for TB management.14 The recommended TB treatment regimen is 6 months of treatment involving a 2-month intensive phase of daily rifampicin (RMP), isoniazid (INH), pyrazinamide and ethambutol followed by a 4-month continuation phase of daily INH and RMP. Treatment is initiated at the hospital, and for new patients it is continued either at the hospital or at the nearest health centre. All retreatment patients are admitted to hospital for 2 months and follow the WHO standardised recommended TB retreatment regimen.14 Those TB patients diagnosed with HIV are also referred to a separate HIV/AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) clinic for care and support and ART.

The Malawi 2008 ART guidelines that were valid at the time of the study stated that all TB-HIV co-infected patients should start ART regardless of CD4 count after 2 months of anti-tuberculosis treatment unless they were sick, in which case they should start earlier. As all HIV-infected TB patients were recommended to start ART, routine WHO clinical staging, CD4 cell counts or viral load were not routinely done before ART initiation. All HIV-infected TB patients were started on Malawi’s first-line ART regimen of stavudine, lamivudine and nevirapine. All TB outcome data and HIV-related data are recorded in the TB treatment cards and TB patient registers.

Patient sample

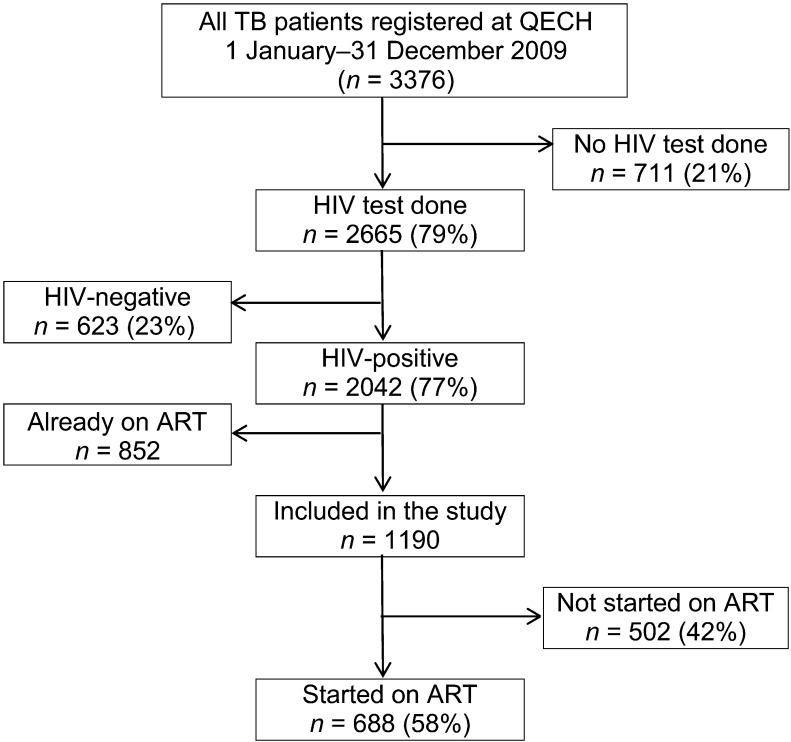

All HIV-infected TB patients (children and adults) registered from January to December 2009 were included in the study if they were not on ART at the time of starting TB treatment (Figure).

FIGURE.

HIV status and ART uptake at QECH, Malawi, 2009. QECH = Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; ART = antiretroviral therapy.

Data variables and data collection instrument

Data variables collected included TB registration number, age, sex, type and category of TB, date of start of TB treatment, whether or not CPT was started, whether or not ART was started, and date of start of ART. The outcome variables were TB treatment outcomes (as defined in Table 1). Information on TB and HIV, including dates of TB treatment and ART initiation, were collected from the TB register and TB treatment cards, respectively. If the dates for ART initiation were missing from the TB treatment cards, the data were obtained from the ART treatment cards whenever possible. Time of ART initiation in relation to TB treatment was divided into <2 months of TB treatment (early) and ≥2 months (late). For the late ART group, the time of ART initiation in relation to TB treatment was divided into 2–4 months and >4 months. All data were transferred into a structured paper-based proforma. Data were collected by four health workers from the NTP and district health offices, all of whom were trained for half a day.

TABLE 1.

Definitions of tuberculosis treatment outcomes used in Malawi

| Treatment success | A patient who completes 6 or 8 months of treatment with or without sputum smear examination during and at the end of treatment |

| Death | A patient who dies during tuberculosis treatment regardless of the cause |

| Failure | A patient found to be sputum smear-positive at 5 months or later during anti-tuberculosis treatment |

| Loss to follow-up | A patient who interrupts treatment for 2 consecutive months or more |

| Transfer out | A patient transferred to another treatment unit in whom the results of treatment are not known |

Analysis and statistics

The data in the structured proforma were extracted and double-entered into EpiData version 3.1 (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark) by two independent data entry clerks. EpiData software was also used to clean for errors and analysis. All records with missing values were excluded from sub-analyses. We classified TB treatment outcomes as treatment success or not, and death as a binary variable to determine the relative probability of successful treatment completion and death, respectively. The Mantel-Haenszel classical method was used to determine relative risks (RRs) for treatment success or death. Comparisons of treatment outcomes between groups were compared using the χ2 test with RRs and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) as appropriate. The level of significance was set at 5%.

The study was approved by the Malawi National Health Science Research Committee and the Ethics Advisory Group of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France. The ethics committees waived the need for patient consent because the study used routine programme data that did not include any personal identifiers and the analysis was done anonymously.

RESULTS

From 1 January to 31 December 2009, 3376 TB patients were registered at QECH. Of these, 2665 (79%) underwent HIV testing and 2042 (77%) tested positive (Figure). Of the 2042 HIV-infected TB patients, 1190 (who were not on ART at the time of starting anti-tuberculosis treatment) were included in the study, of whom 527 (44%) were female. The mean age of all study participants at the time of registration was 32.5 years. The types of TB were as follows: 447 (38%) had smear-negative pulmonary TB (PTB), 435 (37%) smear-positive PTB and 289 (24%) extra-pulmonary TB (EPTB). A small number (19 patients, 2%) had no recorded type of TB. There were 1055 (89%) TB patients categorised as new and 125 (10%) as retreatment TB. Ten (1%) had no recorded category. Six patients were excluded from the treatment outcome analysis because they had no TB treatment outcomes indicated and no exact ART start date recorded on the TB treatment card.

CPT was started in 1042 patients (88%) and ART in 688 (58%). Of those started on ART, 419 (61%) started early (<2 months) and 269 (39%) started ≥2 months after the start of TB treatment.

The association between the time of starting ART and the TB treatment outcomes is shown in Table 2. Patients who started ART early (within 2 months) were not different in terms of age, sex and type/category of TB compared with those who started ART late (≥2 months). Unfortunately, there are no data available to assess whether WHO clinical stage or CD4 counts are similar between the groups, as these measurements were not routinely done. The chance of successfully completing treatment for TB patients starting ART within 2 months of TB treatment initiation was 60% higher than among those starting ART later (RR 1.6, 95%CI 1.4–1.8). The risk of death among patients starting ART early was 75% lower than for those starting ART later (RR 0.25, 95%CI 0.19–0.35). Further analysis was done in the ‘late’ ART starters to compare TB treatment success and other outcomes among those who started ART at 2–4 months with those who started ART at >4 months (Tables 3 and 4). There was no statistically significant difference in treatment outcomes between these two groups.

TABLE 2.

TB treatment outcomes in HIV-infected TB patients starting antiretroviral therapy at Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital

| Time of ART start in relation to start of TB treatment | TB treatment outcomes |

Total n (%) | ||||

| Treatment success n (%) | Died n (%) | Loss to follow-up n (%) | Transfer out n (%) | Failure n (%) | ||

| <2 months | 360 (86) | 47 (11) | 6 (1) | 3 (1) | 1 (0.2) | 417 (100) |

| ≥2 months | 143 (54) | 117 (44) | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | 265 (100) |

| Total | 503 (74) | 164 (24) | 9 (1) | 5 (1) | 1 (0.4) | 682* |

Excludes 6 patients with TB outcomes not recorded (2 early starters and 4 late starters). These patients did not have the exact ART start date indicated on their TB treatment card.

TB = tuberculosis; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; ART = antiretroviral therapy.

TABLE 3.

TB treatment outcomes at 2–4 months and after 4 months

| Time of ART start in relation to start of TB treatment | TB treatment outcomes |

Total n (%) | ||||

| Treatment success n (%) | Died n (%) | Loss to follow-up n (%) | Transfer out n (%) | Failure n (%) | ||

| 2–4 months | 130 (55) | 100 (43) | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | 235 (100) |

| >4 months | 13 (43) | 17 (57) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 30 (100) |

| Total | 143 | 117 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 265 |

TB = tuberculosis; ART = antiretroviral therapy.

TABLE 4.

Relative risk for treatment success and death in relation to time of starting ART among TB-HIV patients

| ART start time | n | Treatment success, unadjusted RR (95%CI) | Death,unadjusted RR (95%CI) |

| <2 months | 417 | 1.6 (1.4–1.8) | 0.25 (0.19–0.35) |

| ≥2 months | 265 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

ART = antiretroviral therapy; TB = tuberculosis; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; RR = relative risk; CI= confidence interval.

There were no significant differences in treatment outcomes between males and females, between new and retreatment TB cases or between patients with different types of TB.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to assess the effect of ART on TB treatment outcomes under routine programme conditions in Malawi. Although collaborative TB-HIV activities have been implemented for several years in Malawi,15 critical TB-HIV indicators are still unfavourable at QECH, particularly uptake for HIV testing and counselling and HIV prevalence among TB patients. Although the ART uptake was higher, at 58%, compared with the national average of 45% in 2009, this was much lower than the national target of 80% set by the Malawi NTP in 2009.7 Given the high prevalence of HIV among those tested (77%), far more patients could benefit from HIV/AIDS treatment, care and support services if the HIV testing rate were higher.

This study demonstrates that in 2009 more TB patients co-infected with HIV and started on ART did so within 2 months of starting anti-tuberculosis treatment (61%) compared with later (39%). Although the 2008 guidelines recommended that ART be started in the continuation phase of TB treatment, more patients were started on ART earlier. Unfortunately, as this study was essentially a record review of registers and treatment cards, the reasons for early start of ART were not clear and cannot be determined from this particular study. The results, however, are comparable to those found in a study in Malawi on adult TB patients, which reported that 51% of HIV-infected TB patients on ART had started HIV treatment before 2 months of TB treatment, 33% between 2 and 6 months and 16% after completion of TB treatment.16 Whatever the reasons for early start of ART, it is evident from this study assessing outcomes under routine programme conditions that TB treatment success rates were better in patients who started ART early rather than later. The death rates of TB patients who started ART early were also considerably lower than in those who started later. The results of this study support the 2011 policy change for ART initiation in Malawi, which recommends starting therapy as soon as possible after anti-tuberculosis treatment has been commenced.17

A major strength of this study is that all data were programme-based and collected from district TB registers, TB treatment cards and ART treatment master cards, which are used for routine patient management and monitoring and evaluation from within a national public system. Large numbers of patients were studied, and we believe that the results are representative of the national situation. Furthermore, the study adhered to STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines for the reporting of observational data.18 However, in line with any operational research study, there were some limitations. Not all the dates on the cards were verified with patients’ ART notes in the health passport books, and as many dates were from patients’ histories collected by TB staff, these may be inaccurate. In programme settings such as this, there are challenges with accuracy and consistency. A systematic enquiry about why most TB-HIV patients started ART in less than 2 months despite the previous policy recommending a later start was also not carried out. Finally, an analysis of patients who were not put on ART was not carried out.

CONCLUSION

This study has shown that under routine programme conditions in 2009 the majority of patients co-infected with HIV and TB and who started ART did so within less than 2 months after the start of TB treatment. Furthermore, early ART initiation within the routine TB programme conditions greatly improved TB treatment outcomes. These data support current policy and guidelines, and early start of ART should be strengthened nationally.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported through an operational research course jointly developed and run by the Centre for Operational Research, International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, Paris, France, and the Operational Research Unit, Médecins Sans Frontières, Brussels. Additional support for running the course was provided by the Centre for International Health, University of Bergen, Norway.

Funding for the course was from an anonymous donor and the Department for International Development, United Kingdom.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control. WHO/HTM/TB/2011.16. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harries A D, Nyangulu D S, Kang’ombe C, et al. Treatment outcome of an unselected cohort of tuberculosis patients in relation to human immunodeficiency virus serostatus in Zomba hospital. Malawi. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:343–347. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(98)91036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Health, Government of Malawi. Malawi National TB Programme annual report for 2011. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harries A D, Libamba E, Schouten E J, et al. Expanding antiretroviral therapy in Malawi: drawing on the country’s experience with tuberculosis. Brit Med J. 2004;329:1163–1166. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7475.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harries A D, Schouten E, Libamba E. Scaling up antiretroviral therapy in resource-poor settings. Lancet. 2006;367:1870–1872. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68809-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ministry of Health, Government of Malawi. Malawi antiretroviral treatment programme quarterly report: results up to 31st December 2011. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ministry of Health, Government of Malawi. Malawi National TB Programme report for 2009. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tyloler-Smith K, Zachariah R, Manzi M, et al. Antiretroviral treatment uptake and attrition among HIV-positive patients with tuberculosis in Kibera, Kenya. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;10:1380–1383. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ministry of Health, Government of Malawi. Treatment of AIDS. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral therapy in Malawi 2008. 3rd ed. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blanc F, Sok T, Laureillard D, et al. Earlier versus later start of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults with tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1471–1481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Havlir D V, Kendall M A, Ive P, et al. Timing of antiretroviral therapy for HIV-1 infection and tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1482–1491. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1013607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karim S S A, Naidoo K, Grobler A, et al. Integration of antiretroviral therapy with tuberculosis treatment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1492–1501. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents. Recommendations for a public health approach. 2010 revision. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Treatment of tuberculosis: guidelines for national programmes. WHO/CDS/STB/2009.420. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ministry of Health, Government of Malawi. TB-HIV operational framework (2007–2011) Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumwenda M, Tom S, Chan A K, et al. Reasons for accepting or refusing HIV services among tuberculosis patients at a TB-HIV integration clinic in Malawi. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:1663–1668. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ministry of Health, Government of Malawi. Clinical management of HIV in children and adults. Malawi integrated guidelines for providing HIV services in antenatal care, maternity care, under 5 clinics, family planning clinics, exposed infants/pre-ART clinics. Lilongwe, Malawi: Ministry of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Elm E, Altman D G, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]