Abstract

Setting:

Cancer patients recorded in Fiji’s National Patient Information System (PATIS) from 2000 to 2010.

Objective:

To identify trends in cervical cancer using case numbers, incidence rates and case fatality in Fiji over the decade 2000–2010.

Design:

Retrospective descriptive and analytical study.

Results:

Between 2000 and 2010, 1234 patients were registered with cervical cancer, of whom 845 (68%) were indigenous Fijians and 357 (29%) were Indians; only 32 (3%) were of other ethnic groups. Mortality rates were much higher among Fijian women, and were far higher in women aged ≥45 years.

Conclusion:

The high incidence rates of cervical cancer in Fijian women between the ages of 35 and 45 years reflect ethnic differences in social norms. The higher case fatality and mortality rates in these groups indicate that more work is needed to improve access to and quality of screening and treatment services.

Keywords: Fiji, cervical cancer, trends

Abstract

Contexte:

Les patientes cancéreuses enregistrées dans le Système National d’Information des Patients (PATIS) aux Iles Fiji entre 2000 et 2010.

Objectif:

Identifier les tendances du cancer cervical en matière de nombre de cas, de taux d’incidence et de létalité aux Iles Fiji au cours de la décennie de 2000 à 2010.

Schéma:

Etude rétrospective descriptive et analytique.

Résultats:

Entre 2000 et 2010, on a enregistré 1234 patients atteints d’un cancer cervical, parmi lesquels 845, soit 68%, étaient des indigènes des Iles Fiji et 357 (29%) des Indiens ; 32 seulement (3%) appartenaient à d’autres groupes ethniques. Les taux de mortalité ont été beaucoup plus élevés chez les femmes des Iles Fiji et encore bien plus élevés chez les femmes âgées de ≥45 ans.

Conclusion:

Les taux élevés d’incidence du cancer cervical chez les femmes des Iles Fiji âgées de 35 à 45 ans reflètent des différences ethniques dans les normes sociales ; leur taux de létalité et de mortalité plus élevés indiquent qu’il y a lieu de s’attacher davantage à l’amélioration de l’accès aux services de dépistage et de traitement et à leur qualité.

Abstract

Marco de referencia:

Los pacientes con diagnóstico de cáncer registrados en el Sistema Nacional de Información de Salud en Fiji entre el 2000 y el 2010.

Objetivo:

Definir las tendencias del cáncer de cuello uterino según el número de casos y las tasas de incidencia y mortalidad en Fiji durante el decenio del 2000 al 2010.

Método:

Fue este un estudio retrospectivo analítico y descriptivo.

Resultados:

Entre el 2000 y el 2010 se registraron 1234 pacientes con cáncer de cuello uterino, de las cuales 845 mujeres eran nativas de Fiji (68%) y 357 provenían de la India (29%); solo 32 mujeres pertenecían a otros grupos étnicos (3%). Las tasas de mortalidad fueron mucho más altas en las mujeres de Fiji y todavía más altas a partir de los 45 años de edad.

Conclusión:

Las altas tasas de incidencia de cáncer de cuello uterino en las mujeres de Fiji entre los 35 y los 45 años de edad corresponden a diferencias étnicas en las normas sociales; las altas tasas de letalidad y mortalidad observadas ponen en evidencia la necesidad de introducir iniciativas que aumenten el acceso a los servicios de detección sistemática y de tratamiento y que mejoren la calidad de estas prestaciones.

Globally, cervical cancer is the second most common type of cancer among women, after breast cancer. Of the 529 000 new cases of cervical cancer and 274 000 deaths recorded worldwide in 2005, >85% were women from low-income countries.1 Secondary prevention using high-quality cytology screening programmes coupled with treatment services is effective, but this is unavailable in many countries.2 An effective vaccine against human papillomavirus (HPV), the agent responsible for virtually all cases of cervical cancer, offers great promise for primary prevention,2 but it is not yet universally available.

Fiji is a small Pacific island nation of 837 000 people, comprised of two main ethnic groups: indigenous Fijians (I-Taukei, 55%) and Indians (Indo-Fijians, 45%), of whom 292 600 (35%) are women aged ≥15 years.3 According to Ministry of Health data, in 2006 cervical cancer was the most common cancer and the tenth most common cause of death in women in Fiji.4

Although cervical screening was introduced in Fiji in 1967, Fiji has limited capacity to process the smear tests of all women screened,4 and only 10% of women report ever having undergone a cervical smear test.4 The HPV vaccine, introduced in 2009, was made available at no cost to all girls aged 13–16 years; however, the effects of the vaccine on cancer incidence will not be seen for some time.

Despite high rates of cervical cancer in Fiji, relatively little research has been undertaken to identify those groups of women most at risk and trends over time. This study describes and examines the characteristics of women diagnosed with cervical cancer over the decade 2000–2010.

METHODS

Design

This was a retrospective descriptive and analytical study.

Setting and participants

The Republic of Fiji is located in the South Pacific, north of New Zealand and east of Australia. Prior to 2002, data on cervical and other cancers in Fiji were recorded in divisional hospitals in a local cancer registry and then transferred monthly to the Ministry of Health, Suva, for database entry. Since 2002, the system has improved dramatically, and cervical cancer data are now collected through an online national patient health information system (PATIS), and collated at the Health Information Unit at the Ministry of Health, Suva. All records from 2000 were transferred to PATIS when it was introduced in 2002, including data from various data sources (laboratory reports, mortality data and in-patient records). We included in our study all patients recorded as having cervical cancer (invasive disease as well as carcinoma in situ, cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia and squamous intra-epithelial lesions) in PATIS from January 2000 to December 2010 inclusive.

Data analysis

Data in PATIS included diagnosis, age and ethnic group. We validated and corrected the data on case numbers and deaths by double checking with Ministry of Health staff working closely with the data sets and with clinicians who enter data into PATIS, and cross-checked PATIS data with data on the death register. Annual incidence and mortality rates were estimated by dividing the numbers of cases and deaths recorded in PATIS by the annual population of women aged ≥15 years (population at risk) from 2000 to 2010, obtained from the Fiji Bureau of Statistics.5 Numbers, rates and proportions were calculated for cancer cases and deaths by ethnic and age group for each year from 2000 to 2010. Case fatality was calculated by dividing the number of deaths by the number of cases for each year, and overall case fatality calculated using a decade of death and case numbers. We verified diagnoses using pathology and histopathology records. Where there were discrepancies, we checked patient records manually. We sampled more than a hundred patients in the database, but were only able to locate 75% of the pathology records. We entered all data into an electronic pro forma, checking for completeness and accuracy prior to analysis.

Ethics

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Advisory Group of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (EAG 59/11) and from the Fiji Ministry of Health National Ethics Committee, Suva, Fiji.

RESULTS

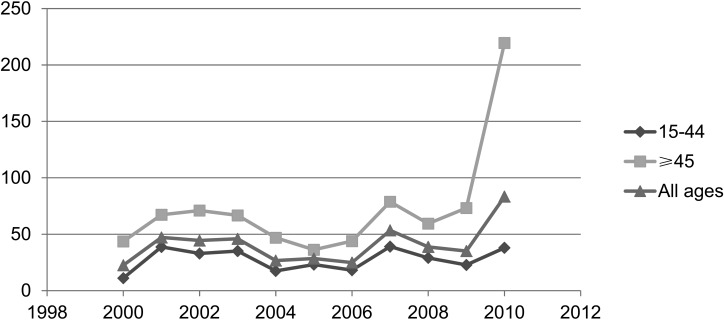

Between 2000 and 2010, 1234 patients were registered with cervical cancer, of whom 845 (68%) were indigenous Fijians and 357 (29%) were Indians; only 32 (3%) registered cases were women from other ethnic groups. Mortality rates were much higher among Fijian women, and far higher in women aged ≥45 years. Incidence rates were stable over much of the decade, but with a marked increase from 2009 and much higher rates among older women (Figure 1). The rates between 2000 and 2007 were far higher among indigenous Fijian than among Indian women; the difference between younger women is particularly marked (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Annual cervical cancer incidence rates (per 100 000) by age group, Fiji, 2000–2010.

TABLE 1.

Annual incidence rates (per 100 000) of cervical cancer in Indigenous Fijian and Indian women by age group, 2000–2007*

| Year | Indigenous Fijian |

Indian |

||||

| 15–44 years | ≥45 years | ≥15 years | 15–44 years | ≥45 years | ≥15 years | |

| 2000 | 17 | 46 | 26 | 4 | 41 | 6 |

| 2001 | 45 | 76 | 54 | 31 | 57 | 15 |

| 2002 | 42 | 104 | 61 | 21 | 33 | 10 |

| 2003 | 51 | 88 | 62 | 14 | 43 | 9 |

| 2004 | 20 | 51 | 29 | 14 | 42 | 8 |

| 2005 | 28 | 43 | 33 | 9 | 26 | 15 |

| 2006 | 25 | 44 | 31 | 9 | 25 | 15 |

| 2007 | 41 | 90 | 56 | 22 | 66 | 37 |

Population data by age and ethnic group were unavailable for 2007–2010.

A total of 663 deaths from cervical cancer were recorded between 2000 and 2010. Almost a third (27%) of cervical cancer deaths among Fijian women occurred in those aged <45 years, compared with only 12% among Indian women in the same age group. Indigenous Fijian women suffer a far higher burden of death due to cervical cancer, and at an earlier age than Indo-Fijian women: 485 (73%) of the total deaths were among Fijian women compared to 161 (24%) in Indian women and 17 (3%) among women from other ethnic groups (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Numbers of cervical cancer deaths by age group and ethnic group (Fijian and Indian), 2000–2010, Fiji

| Year | Indigenous Fijian |

Indian |

||||

| 15–44 years | ≥45 years | All ages | 15–44 years | ≥45 years | All ages | |

| 2000 | 14 | 31 | 45 | 1 | 7 | 8 |

| 2001 | 5 | 13 | 18 | 1 | 6 | 7 |

| 2002 | 14 | 14 | 28 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| 2003 | 5 | 37 | 42 | 2 | 11 | 13 |

| 2004 | 3 | 30 | 33 | 0 | 18 | 18 |

| 2005 | 22 | 39 | 61 | 1 | 17 | 18 |

| 2006 | 14 | 31 | 45 | 3 | 17 | 20 |

| 2007 | 10 | 42 | 52 | 7 | 12 | 19 |

| 2008 | 17 | 40 | 57 | 1 | 21 | 22 |

| 2009 | 13 | 47 | 60 | 1 | 12 | 13 |

| 2010 | 15 | 29 | 44 | 2 | 16 | 18 |

| Total | 132 | 353 | 485 | 19 | 142 | 161 |

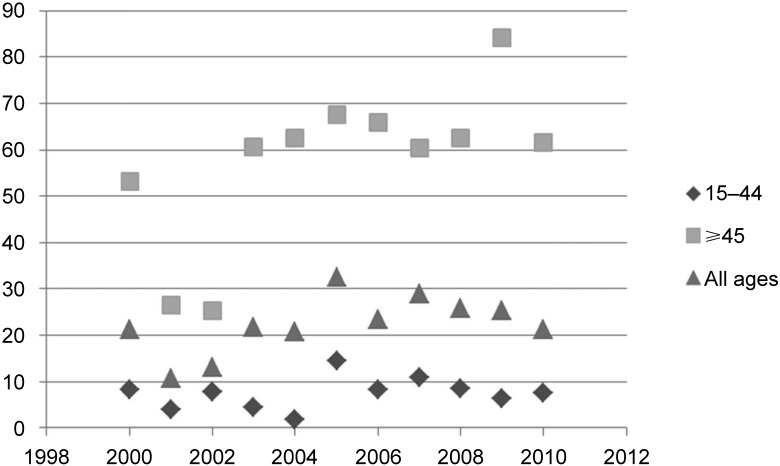

Mortality rates have been largely stable overall since 2002 for those aged 15–44 years and all ages, but are very high among older women, although in 2009 this showed a sharp decline (Figure 2). However, mortality rates were higher among Fijian women (Table 3). Over the decade of the study, almost one in every two women diagnosed with cervical cancer (54%) died. For a few years, annual case fatality rate exceeded 100%, due to patients diagnosed in one year dying in another (Table 4).

FIGURE 2.

Annual cervical cancer mortality rates (per 100 000) by age group, Fiji, 2000–2010.

TABLE 3.

Cervical cancer mortality rates (per 100 000) by age group and ethnic group (Fijian and Indian), 2000–2007, Fiji*

| Year | Indigenous Fijian |

Indian |

||||

| 15–44 years | ≥45 years | All ages | 15–44 years | ≥45 years | All ages | |

| 2000 | 14.3 | 79.6 | 32.9 | 1.2 | 20.4 | 6.8 |

| 2001 | 5.0 | 32.1 | 12.8 | 1.2 | 17.0 | 6.0 |

| 2002 | 13.8 | 33.2 | 19.5 | 0.0 | 13.6 | 4.3 |

| 2003 | 4.8 | 85.2 | 28.6 | 2.5 | 29.3 | 11.1 |

| 2004 | 2.9 | 66.9 | 22.0 | 0.0 | 47.0 | 15.4 |

| 2005 | 20.7 | 84.3 | 39.9 | 1.3 | 43.6 | 15.5 |

| 2006 | 13.0 | 65.2 | 29.0 | 4.0 | 43.2 | 17.5 |

| 2007 | 9.0 | 89.9 | 32.9 | 9.0 | 29.4 | 16.1 |

Population data by age and ethnic group were unavailable for 2007–2010.

TABLE 4.

Cervical cancer cases, numbers of deaths and case fatalities, all ethnic groups, Fiji, 2000–2010

| Year | Cervical cancer cases n | Deaths n | Case fatality % |

| 2000 | 57 | 54 | 95 |

| 2001 | 121 | 27 | 22 |

| 2002 | 116 | 34 | 29 |

| 2003 | 121 | 57 | 47 |

| 2004 | 71 | 55 | 77 |

| 2005 | 69 | 79 | 114 |

| 2006 | 69 | 65 | 94 |

| 2007 | 137 | 74 | 54 |

| 2008 | 120 | 80 | 67 |

| 2009 | 104 | 75 | 72 |

| 2010 | 249 | 63 | 25 |

| Total | 1234 | 663 | 54 |

DISCUSSION

Our study has identified important trends and patterns in cervical cancer numbers, incidence, mortality and case fatality in Fiji. It has also highlighted major problems with the recording of cervical cancer.

Although the number of women in Fiji reported in the national register with cervical cancer has increased over the past decade, crude incidence rates have largely been stable, suggesting that the increase has been more a reflection of population growth than an increase in disease occurrence. It may also reflect improved diagnosis: screening identifies cases that might otherwise have been missed or misdiagnosed. However, from 2009 there was an apparent upswing in incidence. This could reflect a number of factors, including changes in the prevalence of risk factors and/or major changes in diagnosis and recording practices. Over recent decades, changes in prevalence of the known major risk factors for cervical cancer, such as early age at first intercourse, contraceptive use, tobacco smoking, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and HPV infection, may have played a part.6

The lead times for cervical cancer progression from pre-invasive to invasive cancer are generally around 5–10 years,7 so to have had an impact on disease incidence in the past decade, such factors would have had to be exerting their effects over the previous decade or decades. There are no data available on time trends in HPV prevalence in Fiji. However, the two HPV types most commonly associated with cervical cancer, 16 and 18, were found in 99% of cervical biopsies from a group of women with cervical neoplasia examined in a study in Suva in 2010.8 No data are available on changes in age at first intercourse, contraceptive use is reportedly relatively low, and smoking remains uncommon among women (<5%) and HIV prevalence low, at around 0.1%.9 Unfortunately we were unable to undertake stratified analyses based on tumour stage, as these data were not reliably recorded in the system.

The number of women whose deaths were attributed to cervical cancer is high, but has fluctuated over the years (range 31–80 per year). Mortality rates have been high but stable over the decade, but with marked age group and ethnic differences. The marked differences in cervical cancer incidence and mortality between the main ethnic groups suggest there are distinct epidemics. There is a possibility of differential genetic susceptibility, but we hypothesise that these differences largely reflect differences between indigenous and Indian Fijian women in patterns of risk factors and behaviours, patterns of HPV infection and utilisation of preventive and treatment services. Case fatality rates show a steady decline over the last three years of the decade, suggesting improvements in early detection and case management.

Our study had several strengths: we analysed a decade of existing national data and, where possible, validated and corrected the data by checking with staff working with data sets, clinicians entering data on PATIS and with data on the death register. We also adhered to the STROBE (strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology) guidelines for observational studies.10

Limitations include uncertainty about the completeness and quality of the available data. In particular, the completeness of the register is doubtful for 2005 and 2006, when the number of cases was low compared to the years immediately before and after. We can only speculate as to the reasons for this: failure by health staff to submit reports, loss of data between clinical diagnosis and entry into the register, perhaps associated with the introduction of the PATIS system in 2002, or interruptions to the usual operations of the health information system for a number of reasons, such as power and telecommunications outages or the military coup in 2006.

The quality of some data is also a matter of concern. It is likely that in some instances, where there were inexperienced medical staff working with limited diagnostic support, other cancers of the female genital tract could have been miscategorised as cervical cancer and vice versa. Furthermore, while we cross-checked data on deaths attributable to cervical cancer with the death register, it is likely that the deaths of some women in remote areas of Fiji were not counted. The available data may thus underestimate true mortality and case fatality. In addition, we were able to locate only three quarters of the records needed to validate the data entered in PATIS. Furthermore, it is unclear from the cancer register whether the diagnosis of cervical cancer captured only patients with invasive cancers or whether it included all cases with neoplastic lesion.

Our data show generally higher rates of cervical cancer in Fiji, particularly among indigenous Fijian women, than in other Melanesian countries.1 These differences may reflect a real difference, the different age distributions between these countries, relative undercounting in these countries (countries such as Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands have far less well-developed diagnostic and surveillance infrastructures than Fiji and, given the extent of sexually transmitted diseases and more than a decade of HIV infection in Fiji, we might expect a concomitantly higher rate of cervical cancer than is documented), or a combination of the above.

These findings have important implications for the collection of cancer data, and for cervical cancer prevention and treatment in Fiji. First, the completeness and quality of cancer data are critically important to effective planning, targeting and monitoring of public health and clinical treatment services.11 Our finding of yearly variations in histopathology recording in the register in the last decade is of concern, as without such details the ability to track treatment and health outcomes in relation to type and stage of disease at diagnosis is limited.2 Second, cervical screening programmes are of proven effectiveness in reducing cervical cancer incidence and mortality when they are accessed by the majority of women.12 A large population survey conducted in Fiji between 2004 and 2007 found that fewer than 10% of eligible women had ever undergone a smear test.13 Continued efforts are therefore needed to promote screening, and to make it available and as accessible as possible, together with providing information about risk factor mitigation such as condom use and smoking cessation. If screening is possible only once in a woman’s life, based on our data it should be undertaken in women between the ages of 35 and 44 years.

Third, the high case fatality among women with cervical cancer in Fiji suggests that treatment may be accessed too late or that it may be inadequate. Greater awareness of the early signs and symptoms of cervical cancer should be promoted among women and encouragement given to present for medical examination as soon as symptoms occur. However, sex inequity and stigma may make it too difficult for many women to overcome the many barriers to timely access.14 In addition, there is a need for improvements in the medical and surgical management of cervical cancer in Fiji.

Fourth, attaining high and sustained levels of coverage of all children with HPV vaccination should be accorded priority to avert a future heavy burden of cervical and other HPV-induced genital cancers. These programmes and services should be monitored to ensure reach and effectiveness, in particular among indigenous Fijian women, who bear a greater burden of risk, disease and death.

CONCLUSIONS

Our research has shown that improvements are needed in the completeness and quality of data collection, and that more efforts are needed to improve awareness, screening coverage and clinical management. The HPV vaccination programme should be sustained. Research is urgently needed to better understand the determinants of Fiji’s high burden of cervical cancer and high mortality, particularly in the indigenous Fijian population. In particular, research is required to address gaps in knowledge of the prevalence of HPV infection in the population, adolescent sexual behaviour in Fiji, and factors limiting patient access to cervical cancer screening and treatment services, so that appropriately targeted interventions can be designed and implemented.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported though an operational research course jointly developed and run by the Fiji National University, Suva, Fiji; the Centre for Operational Research, International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union), Paris, France; the Operational Research Unit, Médecins Sans Frontières, Brussels; the National Institute for Health Innovation, School of Population Health, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand; the Woolcock Institute of Medical Research, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia; and the Centre for International Child Health, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

Funding for this course came from the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, The Union and the World Health Organization.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization/Insitut Catala d’Ontologia Information Centre on HPV and Cervical Cancer. Human papillomavirus and related cancers in Fiji: summary report 2010. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, ICO; 2010. http://www.who.int/biologicals/areas/vaccines/hpv_labnet/HPV_LabNet_Newsletter_No_7.pdf Accessed March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Comprehensive cervical cancer control. A guide to essential practice. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiji Islands Bureau of Statistics. Facts and figures. Suva, Fiji: Bureau of Statistics Fiji; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fiji Ministry of Health. Annual report. Suva, Fiji: Fiji Ministry of Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiji Islands Bureau of Statistics. Facts and figures as of July 1st 2005. Suva, Fiji: Bureau of Statistics Fiji; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munoz N, Bosch F, de Sanjose S, et al. The causal link between human papillomavirus and invasive cervical cancer: a population-based case-control study in Colombia and Spain. Int J Cancer. 1992;53:743–749. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910520513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holowaty P, Miller A B, Rohan T, To T. Natural history of dysplasia of the uterine cervix. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:252–258. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.3.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sepehr N, Tabrizi A B H, Irwin Law C D, et al. Human papillomavirus genotype prevalence in cervical biopsies from women diagnosed with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia or cervical cancer in Fiji. Sexual Health. 2011;8:338–342. doi: 10.1071/SH10083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sladden T. Twenty years of HIV surveillance in the Pacific—what do the data tell us and what do we still need to know? Pac Health Dialog. 2005;12:23–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Von Elm E, Altman D, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453–1457. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valsecchi MG, Steliarova-Foucher E. Cancer registration in developing countries: luxury or necessity? Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:159–167. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eddy D M. Screening for cervical cancer. Intern Med. 1990;113:214–226. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-113-3-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.University of Melbourne Centre for International Child Health and Australia National University National Centre for Epidemiology and Population. Mission report. Burden of cervical cancer and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in Fiji (2004–2007) Manila, Philippines: World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knaul F, Bhadelia A, Gralow J, Ornelas H, Langer A, Frenk J. Meeting the emerging challenge of breast, cervical cancer in low and middle income countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;119(Suppl 1):S85–S88. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]