Abstract

Setting:

Médecins Sans Frontières Clinic for sexual gender-based violence (SGBV), Nairobi, Kenya.

Objectives:

Among survivors of SGBV in 2011, to describe demographic characteristics and episodes of sexual violence, medical management, pregnancy and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) related outcomes.

Design:

Retrospective review of clinical records and SGBV register.

Results:

Survivors attending the clinic increased from seven in 2007 to 866 in 2011. Of the 866 survivors included, 92% were female, 34% were children and 54% knew the aggressor; 73% of the assaults occurred inside a home and most commonly in the evening or at night. Post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV was given to 536 (94%), prophylaxis for sexually transmitted infections to 731 (96%) and emergency contraception to 358 (83%) eligible patients. Hepatitis B and tetanus toxoid vaccinations were given to 774 survivors, but respectively only 46% and 14% received a second injection. Eight (4.5%) of 174 women who underwent urine pregnancy testing were positive at 1 month. Of 851 survivors HIV-tested at baseline, 96 (11%) were HIV-positive. None of the 220 (29%) HIV-negative individuals who returned for repeat HIV testing after 3 months was positive.

Conclusion:

Acceptable, good quality SGBV medical care can be provided in large cities of sub-Saharan Africa, although further work is needed to improve follow-up interventions.

Keywords: SGBV, Kenya, HIV, medical management, operational research

Abstract

Contexte:

Dispensaire de Médecins Sans Frontières pour la violence sexuelle basée sur le genre (SGBV), Nairobi, Kenya.

Objectifs:

Parmi les survivants des SGBV en 2011, décrire les caractéristiques démographiques et les épisodes de violence sexuelle, la prise en charge médicale, la grossesse et les effets liés au virus de l’immunodéficience humaine (VIH).

Schéma:

Revue rétrospective des dossiers cliniques et du registre SGBV.

Résultats:

Le nombre de survivants fréquentant le dispensaire a augmenté de sept en 2007 à 866 en 2011. Sur les 866 survivants inclus, 92% étaient de sexe féminin, 34% des enfants et 54% connaissaient leur agresseur. Soixante-treize pour cent des agressions sont survenues à l’intérieur d’un foyer et le plus souvent le soir ou la nuit. Une prophylaxie du VIH après exposition a été fournie à 536 (94%), une prophylaxie pour les infections sexuellement transmissibles à 731 (96%) et une contraception d’urgence à 358 (83%) des patients éligibles. On a administré des vaccins contre l’hépatite B et la toxine du tétanos à 744 survivants, mais respectivement 46% et 14% seulement ont reçu une deuxième injection. Chez huit (4,5%) des 174 femmes les tests urinaires de grossesse ont été positifs à 1 mois. Au départ, 851 survivants ont été testés pour le VIH, parmi lesquels 96 (11%) étaient séropositifs. Aucun des 220 (29%) séronégatifs pour le VIH qui sont revenus pour un test VIH répété après 3 mois n’a été positif.

Conclusion:

On peut administrer des soins médicaux acceptables et de bonne qualité en cas de SGVB dans de grandes villes d’Afrique sub-saharienne. Il s’agit toutefois de veiller davantage à l’avenir à améliorer les interventions de suivi.

Abstract

Marco de referencia:

Un consultorio de atención de la violencia sexual y de género (SGBV) a cargo de Médicos Sin Fronteras en Nairobi, Kenia.

Objetivos:

Definir las características demográficas de las víctimas y los episodios de violencia de los sobrevivientes de SGBV en el 2011 y describir el tratamiento médico y los desenlaces relacionados con embarazos e infección por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH) durante la prestación de atención sanitaria.

Métodos:

El estudio consistió en un análisis retrospectivo de los expedientes clínicos y del registro de los casos de SGBV.

Resultados:

El número de sobrevivientes que acudieron al consultorio aumentó de siete en el 2007 a 866 en el 2011. De los 866 sobrevivientes incluidos en el estudio, 92% eran de sexo femenino, 34% eran niños y 54% conocían al agresor. El 73% de las agresiones tuvo lugar dentro de un hogar y generalmente al final de la tarde o en la noche. Se suministró profilaxis antivírica posterior a la exposición al VIH en 536 casos (94%), profilaxis contra las infecciones de transmisión sexual en 731 casos (96%) y se ofrecieron anticonceptivos de urgencia a 358 pacientes (83%) que cumplían con los requisitos. Se administró la vacuna contra la hepatitis B y el toxoide tetánico a 774 sobrevivientes, pero solo el 46% recibió la segunda inyección anti-hepatitis B y el 14% la segunda dosis del toxoide tetánico. Ocho de las 174 mujeres (4,5%) en quienes se practicó una prueba de embarazo en orina 1 mes después de la agresión obtuvieron un resultado positivo. Se practicó inicialmente la prueba diagnóstica del VIH a 851 sobrevivientes, de los cuales 96 (11%) fueron positivos. Ninguna de las 220 personas negativas frente al VIH (29%) que acudieron 3 meses después con el fin de repetir la prueba obtuvo un resultado positivo.

Conclusión:

Es posible prestar a las víctimas de SGBV una atención que sea aceptable y de buena calidad en las grandes ciudades de África subsahariana, pero se precisan nuevas iniciativas que mejoren las intervenciones de seguimiento.

Many countries in sub-Saharan Africa have experienced rapid development and urbanisation in recent years. This, along with internal instability and other factors, has led to sexual gender-based violence (SGBV) becoming a major problem.1–5 Addressing SGBV is important given its physical, psychological and social consequences. The consequences in terms of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, unwanted pregnancies and long-term psychological effects are not well described, especially in sub-Saharan African countries.

Although there are no national data on the prevalence of SGBV in Kenya, 1400 cases of rape, estimated at only 11% of the actual number of rape cases, were reported during the post-election violence between December 2007 and March 2008.6 These estimates suggest that, as in several other sub-Saharan African countries, there is a need to provide adequate and effective prevention, care and protection strategies for SGBV in Kenya.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has been offering care to survivors of SGBV in Eastern Nairobi, Kenya, since 2007. It is one of the few organisations in the country to offer a comprehensive package of care to such victims. The present study attempts to fill the knowledge gap and describe the care and support offered to SGBV survivors in a slum in Nairobi, Kenya, in 2011. Specific objectives were to describe amongst SGBV survivors: 1) individual demographic characteristics and episodes of sexual violence, 2) medical and psychological management, including medico-legal certification, and 3) HIV infection and pregnancy outcomes associated with the provision of care.

METHODS

Study design

This was a cross-sectional study involving a retrospective review of patient files and an SGBV register.

Study site

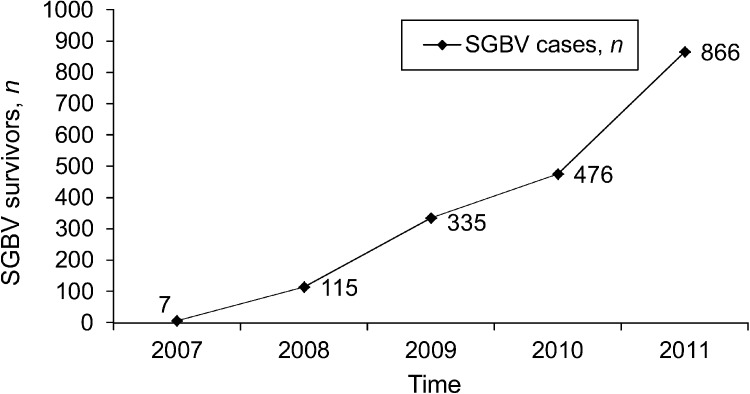

The MSF clinic for SGBV victims has been operating in Mathare Eastleigh, Eastern Nairobi, Kenya, since 2008. Over the last 5 years, the number of persons seeking care for SGBV in the MSF clinic has progressively increased (Figure). This part of Nairobi has a population of 2.2 million, including various migrant groups, and is more affected by poverty and unemployment than other areas of the city. Since March 2011, the SGBV clinic has offered care 7 days a week, 24 hours a day. It has six rooms (administrative, paediatric, examination, counselling, psychologist and patient waiting area) and is staffed by four clinical officers, four counsellors, one psychologist and 10 support workers. Survivors of SGBV who present at the clinic are registered, seen by a counsellor and then examined by a clinical officer. Complicated cases may be referred to a psychologist and/or a medical officer.

FIGURE.

Number of SGBV survivors attending the Médecins Sans Frontières clinic of Mathare, Nairobi, Kenya, between 2007 and 2011. SGBV = sexual gender-based violence.

All SGBV survivors undergo 1) clinical and psychological assessment; 2) HIV testing using rapid diagnostic blood tests, following a parallel algorithm in accordance with national guidelines; 3) urine pregnancy testing; 4) testing for syphilis and hepatitis B (rapid blood tests); and 5) urine analysis; and, if patients are seen within 5 days of the assault, high vaginal or anal swab for spermatozoa collection and possible DNA identification of the assailant. Survivors presenting with severe lesions or requiring examination under anaesthesia are referred to the Nairobi Children and Women’s Hospital or to the Kenyatta National Hospital. All survivors are examined clinically to compile an inventory of their lesions and to gather forensic evidence.

Medical interventions include: 1) post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for HIV infection with a combination of zidovudine, lamivudine and lopinavir/ritonavir for 30 days for HIV-negative persons who present within 72 h of the assault and have no contraindications; 2) emergency contraception (levonorgestrel 1.5 mg in a single dose) for female survivors (teenagers who have reached puberty, women not yet in menopause or who have not had their periods at the time of the consultation), and who present within 5 days of the assault; 3) prophylaxis for sexually transmitted infections (STI) with azithromycin, cefixime and tinidazole; 4) hepatitis B vaccination (initial injection followed by two further injections at days 7 and 21); and 5) anti-tetanus vaccination (initial injection followed by two further injections at months 1 and 6), or simple booster according to the survivor’s needs.

It is standard practice to issue survivors with a medico-legal certificate and a post-rape care form. These can be used as legal evidence of the assault.

Study participants

All survivors who attended the MSF SGBV clinic between 1 January and 31 December 2011 were included in the study.

Data collection

Information was extracted from patient case files using standardised forms and the SGBV register of the MSF clinic. Data collected included age; sex; number and type of assailants; day, time and place of assault; date of admission to the clinic; HIV testing and results on admission and 3 months later; urine pregnancy test on admission and 1 month later; referrals to tertiary hospitals; medical interventions provided (PEP, treatment for STIs, emergency contraception, psychological counselling and referral); and number of medical certificates written and given to clients. No survi-vors were interviewed for the study. The data were entered into EpiData, version 3.1 (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark).

Statistical methods

The data were analysed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and EpiData Analysis 2.1 (EpiData Association). Frequencies and percentages were used to describe categorical variables.

Ethics considerations

This study met the MSF Ethics Review Board criteria for analysis of routinely collected programme data.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics and details of sexual assault

Of 866 survivors of SGBV, 73% presented within 72 h of the assault and 78% within 5 days. Individual demographic characteristics and description of the episode of sexual violence are shown in Table 1. The majority of the SGBV survivors (92%) were females, and one third were children aged <14 years. While two thirds of aggressors of children and adolescents (n = 482) were family members, relatives or known civilians, those of older survivors were generally unknown civilians. In 77% of cases (n = 645), particularly among children (n = 266, 93%), the assault was carried out by a single aggressor, while among adolescents and adults (n = 570), 30% of assaults were carried out by more than one aggressor. Regardless of age, the most common place of SGBV was inside the home (n = 539, 73%). Among adults, 19% (n = 74) of assaults took place outside of the home. Finally, the most common time for SGBV was night time (period between 6 pm and midnight), although this varied according to age; children were more commonly assaulted in the afternoon (between noon and 6 pm).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of survivors of SGBV and description of episodes of sexual violence stratified by age group among those seeking care, Médecins Sans Frontières Clinic, Mathare, Nairobi, Kenya*

| Characteristic | Age < 14 years | Age 14–17 years | Age ≥18 years | Total |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| All survivors | 292 (34) | 190 (22) | 380 (44) | 866 (100) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 256 (88) | 183 (96) | 351 (92) | 792 (92) |

| Male | 36 (12) | 7 (4) | 29 (8) | 72 (8) |

| Type of aggressor | ||||

| Relative | 38 (14) | 15 (8) | 11 (3) | 64 (8) |

| Known civilian | 162 (59) | 103 (56) | 120 (32) | 385 (46) |

| Unknown civilian | 75 (27) | 63 (34) | 238 (64) | 378 (45) |

| Military or police | — | 3 (2) | 1 (<1) | 4 (<1) |

| Unknown | 17 | 6 | 10 | 35 |

| Number of aggressors | ||||

| 1 | 266 (93) | 148 (81) | 229 (60) | 645 (77) |

| 2–4 | 20 (7) | 29 (16) | 118 (31) | 168 (20) |

| ≥5 | — | 5 (3) | 20 (9) | 25 (3) |

| Unknown | 6 | 8 | — | 28 |

| Place of aggression | ||||

| Living space at home | 194 (82) | 147 (84) | 195 (61) | 539 (73) |

| Public place | 15 (6) | 14 (8) | 63 (20) | 92 (12) |

| Work place | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 10 (3) | 14 (2) |

| School | 12 (5) | 2 (1) | 1 (< 1) | 15 (2) |

| Other | 13 (6) | 11 (6) | 53 (16) | 77 (11) |

| Unknown | 56 | 14 | 58 | 129 |

| Time of aggression | ||||

| 00.00–06.00 | 14 (8) | 14 (13) | 74 (25) | 102 (18) |

| 06.00–12.00 | 19 (12) | 10 (9) | 23 (8) | 52 (9) |

| 12.00–18.00 | 77 (46) | 30 (28) | 46 (16) | 154 (27) |

| 18.00–24.00 | 57 (34) | 54 (50) | 148 (51) | 261 (46) |

| Unknown | 125 | 82 | 89 | 297 |

Of the 866 survivors, 4 were of unknown age, all female: aggressors were unknown civilians for 2 and unknown for 2; number of aggressors was one for 2 survivors, four for 1 and unknown for 1. The place of assault was in the home for 3 survivors and unknown for one.

SGBV = sexual gender-based violence.

Medical and psychological care

A description of compliance with the administration of PEP with antiretroviral drugs, emergency contraception and treatment of STIs according to clinic guidelines is shown in Table 2. PEP and STI treatment were administered correctly in the majority of eligible cases (n = 536, 94%, and n = 731, 96%, respectively), while emergency contraception was administered correctly in just over 80% of eligible cases.

TABLE 2.

Medical treatment actually provided to eligible SGBV survivors at the Médecins Sans Frontières Clinic, Nairobi, Kenya

| Medical treatment | Survivors who should have received treatment according to clinic guidelines | Eligible survivors who actually received medical treatment |

| n | n (%) | |

| Post-exposure prophylaxis with antiretroviral drugs | 570 | 536 (94) |

| Emergency contraception | 430 | 358 (83) |

| Treatment for sexually transmitted infections | 761 | 731 (96) |

SGBV = sexual gender-based violence.

A total of 774 patients (89%) received initial hepatitis B and anti-tetanus toxoid vaccinations. However, for both, there was high attrition at the first and second follow-up injections; this was particularly marked for the anti-tetanus vaccine (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Vaccination for hepatitis B and tetanus at baseline and follow-up, Médecins Sans Frontières Clinic, Nairobi, Kenya

| Vaccination | Baseline injection | First follow-up injection | Second follow-up injection |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Hepatitis B | 774 (100) | 471 (61) | 354 (46) |

| Tetanus | 774 (100) | 347 (45) | 108 (14) |

Every survivor received psychological counselling in the clinic. Only 16 (2%) were assessed as having sufficiently severe mental trauma for referral to a psychologist. A medico-legal certificate was given to 572 (66%) survivors. A certificate was written but not given to 243 (28%); the remainder declined the need for a certificate.

HIV and pregnancy outcomes

Of the 528 women who were not pregnant at admission, 174 underwent retesting of urine for pregnancy 1 month later; 8 (4.5%) were found to be pregnant. Of the 866 survivors, 851 (98%) were tested for HIV infection on admission, and 96 (11.3%) were HIV-positive. Only 220 (29%) of those who tested HIV-negative returned after 3 months for re-testing. Of these, 179 (81%) had received PEP. No survivors were found to have seroconverted at 3 months.

DISCUSSION

This is one of the first studies from Africa to report on medical management and specific outcomes of SGBV survivors.7 The majority of the SGBV survivors were females, and about one third were children. While the number and proportion of male survivors was small, this study is likely to underestimate the true prevalence of SGBV among both men and women. Population-based data from the Democratic Republic of Congo showed, for example, that almost a quarter of men had experienced some form of SGBV during their lifetime,8 and that failure to seek care may be related to feelings of guilt, fear and shame. In half of the SGBV cases, the aggressor was either a family member or a friend. A single aggressor was usually involved, the home environment was the place of assault in over half of cases, and, except for assaults on children, the assault often took place during the evening or night.

In general, uptake of medical treatment with PEP and treatment of STIs for those needing these interventions was good. Emergency contraception was not provided to 17% of eligible survivors, due to family planning method use at the time of the aggression, menstruation at admission to the clinic or refusal by the survivor. Hepatitis B and anti-tetanus toxoid vaccinations were given to the majority of survivors. Those who did not receive the injections were mainly children with an updated immunisation schedule. The main problem with these interventions was the large attrition rate for the second and third injections, particularly for tetanus vaccine, which was scheduled to be given 1 and 6 months after the first injection. There are a number of possible reasons for this, including a desire not to return to the clinic as a result of psychological trauma, a lack of motivation from the survivors, an oversight, a misunderstanding of the appointment date and transport costs.

Only a small minority of survivors needed specialised psychological attention. Two thirds of survivors received a medico-legal certificate, but we have no information about whether these were taken to the police or used to press charges against perpetrators.

In terms of outcomes, we assessed 1-month pregnancy rates and 3-month HIV conversion rates after the assault. Eight pregnancies were diagnosed on urine testing at 1 month among women who were not pregnant at admission, but it was impossible to determine whether or not these pregnancies resulted from the assault. The uptake of HIV testing on admission was high. Of those found to be HIV-negative, about a quarter were not eligible for PEP, mainly due to delays in presenting to the clinic after the assault. Regardless of whether or not PEP was administered, there was no recorded case of HIV conversion 3 months after the first test. Of concern, however, was the observation that less than a third of patients returned to the clinic for repeat HIV testing.

The strengths of this study are that a large number of survivors were assessed in the clinic using standardised operational procedures and protocols and with a good recording and registration system. As it was the only clinic offering these services to SGBV survivors in Eastern Nairobi, the characteristics of the affected population probably represent what is happening in the community in this part of the city. Limitations include the lack of data on the perpetrators’ age and sex, the absence of recorded information for specific questions and an inability to ascertain whether or not pregnancies were due to the assault.

Despite these limitations, this study identifies important areas for improvement of care. First, although the uptake of medical interventions such as PEP and emergency contraception was good, this could be improved, for example by quarterly reporting of uptake against targets, better definitions about who is eligible for the intervention, and clear explanations about why interventions were not given to individuals. Second, the attrition rates for scheduled follow-up immunisations or visits for urine pregnancy testing or blood testing for HIV were high, and ways to reduce this attrition need to be found. Mobile phone technology is already used in the clinic for patient tracing, but a more organised approach may be considered, especially as this has benefited HIV programmes in the country.9 Special consideration should be given to targeting the 6-month tetanus toxoid injection exclusively for those who really need it, as so few survivors return for this intervention. Alternatively, simplified medical follow-up schedules need to be developed, evaluated and implemented. Third, the rising number of cases of SGBV registered in the last 5 years suggests an unmet demand, and consideration is already being given to starting new clinics elsewhere inside and outside the city.

In conclusion, this study shows that it is feasible and worthwhile to offer SGBV care in large African cities. With standardised procedures and protocols, good quality care can be offered to reduce physical and psychological morbidity. However, further work is required to address some of the deficiencies identified in this study.

Acknowledgments

A special thanks to G Kyalo, who entered the data for the study, to the MSF France field coordinator, J Hurst, who made valuable comments and to the SGBV unit team for their work.

This research was supported through an operational research course that was jointly developed and run by the Centre for Operational Research, International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, France, and the Operational Research Unit, Médecins Sans Fron-tières, Brussels-Luxembourg. Additional support for running the course was provided by the Institute for Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium; the Center for International Health, University of Bergen, Norway. Epicentre, France, and Médecins Sans Frontières–France gave their agreement. MSF France and Epicentre respectively provided material and technical support.

Funding for this study came from Médecins Sans Fron-tières, Paris Operational Center, France.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Amowitz L L, Reis C, Hare-Lyons K, et al. Prevalence of war-related sexual violence and other human rights abuses among internally displaced persons in Sierra Leone. JAMA. 2002;287:513–521. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olley B O, Abraham N, Stein D J. Association between sexual violence and psychiatric morbidity among HIV-positive women in South Africa. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2006;35:143–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunkle K L, Jewkes R K, Brown H C, Gray G E, McIntryre J A, Harlow S D. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet. 2004;363:1415–1421. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hustache S, Moro M-R, Roptin J, et al. Evaluation of psychological support for victims of sexual violence in a conflict setting: results from Brazzaville, Congo. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2009;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tayler-Smith K, Zachariah R, Hinderaker S G, et al. Sexual violence in post-conflict Liberia: survivors and their care. Trop Med Int Health. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03066.x. Aug 12. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kenya Nairobi Rape Statistics between December 30th–April 2008. Posted in the Nairobi, Kenya Forum. Nairobi, Kenya: CSI Nairobi, 2009. http://www.topix.com/forum/ke/nairobi/TIBUT6Q2F7OC0H6IC Accessed April 2013.

- 7.Speight C G, Klufio A, Kilonzo S N, et al. Piloting post-exposure prophylaxis in Kenya raises specific concerns for the management of childhood rape. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson K, Scott J, Rughita B, et al. Association of sexual violence and human rights violations with physical and mental health in territories of the Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. JAMA. 2010;304:553–562. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lester R T, Ritvo P, Mills E J, et al. Effects of a mobile phone short message service on antiretroviral treatment adherence in Kenya (WelTelKenya1): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1838–1845. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61997-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]