Abstract

Setting:

Despite a steep increase in the number of individuals treated for latent tuberculous infection (LTBI), few data are available on how treatment is implemented.

Objective:

To obtain baseline information on initiation and completion of treatment for LTBI in Norway in 2009.

Design:

A descriptive cross-sectional study.

Results:

All 721 patients treated for LTBI in 2009 in Norway were included, of whom 607 (84%) completed treatment. The treatment regimen generally consisted of 3 months of rifampicin and isoniazid. The three main reasons for starting treatment were: 1) countries of origin with high tuberculosis (TB) prevalence, 2) a positive tuberculin skin test, and 3) a positive interferon gamma release assay. The use of directly observed treatment varied by health region and age. The majority of the 34 medical specialists interviewed saw a need for new national guidelines to improve the selection of high-risk patients with LTBI.

Conclusions:

Management of LTBI is in accordance with current guidelines, with a high completion rate. More targeted selection of which patients should be offered preventive treatment is required, and new guidelines and tools to enhance risk assessment are necessary.

Keywords: screening, prophylactic treatment, directly observed therapy, completion

Abstract

Contexte:

En dépit d’une croissance rapide du nombre d’individus traités pour une infection tuberculeuse latente (LTBI), on ne possède que peu de données sur la façon dont le traitement est mis en œuvre.

Objectif:

Obtenir une information de base sur la mise en route et l’achèvement du traitement de la LTBI en Norvège en 2009.

Schéma:

Il s’agit d’une étude transversale descriptive.

Résultats:

On a inclus l’ensemble des 721 patients traités en 2009 en Norvège pour une LTBI, parmi lequels 607 (84%) ont achevé leur traitement. Le régime principal de traitement a consisté en 3 mois de rifampicine et d’isoniazide. Les trois raisons les plus importantes pour la mise en route du traitement ont été : 1) provenir d’un pays où la prévalence de la tuberculose (TB) est élevée, 2) un test cutané tuberculinique positif, et 3) un test positif de libération de l’interféron-gamma. L’utilisation du traitement directement observé a varié en fonction de la région de santé et de l’âge. La majorité des 34 spécialistes médicaux interviewés considère qu’il est nécessaire de disposer de nouvelles directives nationales pour améliorer la sélection des patients à haut risque de LTBI.

Conclusions:

La prise en charge de la LTBI est conforme aux directives actuelles. Le taux d’achèvement est élevé. Une sélection plus ciblée des patients auxquels il faudrait offrir un traitement préventif s’impose. Dès lors, il est nécessaire de disposer de nouvelles directives et de nouveaux outils pour améliorer l’évaluation du risque.

Abstract

Marco de referencia:

Pese al gran aumento del número de personas que reciben tratamiento contra la infección tuberculosa latente (LTBI), existen pocos datos sobre el mecanismo de ejecución de este tratamiento.

Objetivo:

Establecer una información de referencia sobre la iniciación y la compleción del tratamiento de la LTBI en Noruega en el 2009.

Método:

Fue este un estudio transversal descriptivo.

Resultados:

Participaron en el estudio los 721 pacientes tratados por LTBI en el 2009 en Noruega. Seiscientos siete pacientes completaron el tratamiento (84%). El principal régimen terapéutico consistió en 3 meses con rifampicina e isoniazida. Las tres indicaciones más importantes para comenzar el tratamiento fueron 1) el origen de un país con alta prevalencia de tuberculosis (TB), 2) un resultado positivo a la prueba cutánea de la tuberculina, y 3) un resultado positivo a la prueba de liberación de interferón. La aplicación del tratamiento directamente observado difirió según las regiones de salud y la edad de los pacientes. La mayoría de los 34 médicos especialistas que se entrevistaron comunicó la necesidad de contar con nuevas directrices nacionales a fin de optimizar la selección de los casos con alto riesgo en los pacientes con LTBI.

Conclusiones:

El tratamiento de la LTBI se practica en conformidad con las directrices en vigor. La tasa de compleción del tratamiento es alta. Se precisa una selección mejor dirigida de los pacientes a quienes se ofrece el tratamiento preventivo. Por esta razón, es necesario elaborar nuevas recomendaciones y poner a disposición nuevos instrumentos que refuercen la evaluación del riesgo.

Tuberculosis (TB) remains one of the infectious diseases with the highest mortality globally. In 2011, it was estimated that there were 8.7 million new cases of TB worldwide.1 The World Health Organization estimates that around one third of the world’s population has latent tuberculous infection (LTBI). Only a minority of immunocompetent persons infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis will develop active disease.2 However, there is an increased risk for individuals with reduced immunity, particularly among those infected with the human immunodefiency virus (HIV).3,4

Due both to increased immigration from countries with a high TB burden and to the global TB situation, the National Public Institute in Norway recommended in 2003 that the public health service should increase its focus on preventive treatment for LTBI.5 The number of patients receiving preventive treatment in Norway increased from 160 in 2004 to 721 in 2009. All LTBI treatment in Norway is provided by the Public Health Service. Studies indicate that preventive treatment reduces the risk of developing TB by almost 80%, providing that treatment is completed.6,7 However, the treatment dropout rate is high, with completion rates of between 45% and 67%.8–10

Although Norway is a small country, treatment for LTBI is not uniform throughout the country. The purpose of our study was to address the following questions: 1) What are the characteristics of the individuals who receive preventive treatment for LTBI in Norway? 2) How is treatment implemented? 3) How are patients followed up during treatment? and 4) Do we successfully identify those at highest risk of developing active TB and thus can we potentially contribute to reducing the number of TB cases in Norway?

METHODS

The data were obtained through a questionnaire sent to all the TB coordinators of every health trust in Norway and through semi-structured interviews with 34 medical specialists with experience in treating TB. The focus of the interviews was the specialists’ opinions on LTBI treatment and national guidelines.

All patients in Norway who received preventive treatment for LTBI in 2009 were included in the study. All data were recorded on an anonymous form and double entered. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 (IBM Corporation, Somers, NY, USA). The figures were produced using Matlab 2010a (Mathworks Inc, Natick, MI, USA).

For analysis, standard descriptive techniques were used. The correlation between variables was tested using the Exact χ2 test,11 with a general significance level of 0.05. Taking multiple effects into account, we adjusted the significance level using the Bonferroni correction. This led to the use of a significance level of 0.01 for the association of side effects. We estimated a logistic model with treatment completion as outcome and health region, sex, age and origin as predictors.

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Committee of Western Norway.

RESULTS

Data were collected for 721 patients starting preventive treatment for LTBI during the study period from 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2009. Five persons were excluded due to missing data. The demographic characteristics, migration category and treatment regimen of the participants are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Baseline data for 721 patients treated for latent tuberculosis in Norway, 2009

| n (%) | |

| Health region (n = 721) | |

| South-East | 349 (48) |

| West | 130 (18) |

| Central | 82 (11) |

| North | 160 (22) |

| Sex (n = 714)* | |

| Male | 348 (49) |

| Female | 366 (51) |

| Age group, years (n = 716)* | |

| ≤2 | 14 (2) |

| 3–15 | 115 (16) |

| 16–35 | 411 (57) |

| >35 | 176 (25) |

| Origin (n = 713)* | |

| Northern/Western Europe | 112 (16) |

| Southern/Eastern Europe | 69 (10) |

| North America | 0 |

| Central/South America | 8 (1) |

| Asia | 240 (34) |

| Africa | 284 (39) |

| Migration category, (n = 716)* | |

| Ethnic Norwegian | 96 (13) |

| Second generation immigrant | 15 (2) |

| Asylum seeker | 257 (36) |

| United Nations refugee | 63 (9) |

| Family reunion | 149 (21) |

| Work immigrant | 27 (4) |

| Au pair | 44 (6) |

| Unknown | 39 (6) |

| Other† | 24 (3) |

| Time spent in Norway before treatment, years (n = 716)* | |

| <1 | 260 (36) |

| 1–3 | 223 (31) |

| 3–5 | 36 (5) |

| >5 | 78 (11) |

| Born in Norway | 113 (16) |

| Unknown | 6 (1) |

| Treatment strategy (n = 717)* | |

| Daily DOT | 376 (52) |

| Partial DOT‡ | 233 (32) |

| Self-administered | 108 (15) |

Total number <721 due to lack of data.

Including students.

DOT <80% of total treatment days.

DOT = directly observed treatment.

Norway is divided into four health authority regions. The South-East region is the largest, and 48% of the patients were treated there. The distribution of migration categories differed significantly between the four health authority regions (P < 0.001). In particular, the Northern region differed from the rest, with a large number of asylum seekers (60%).

Reasons for treatment

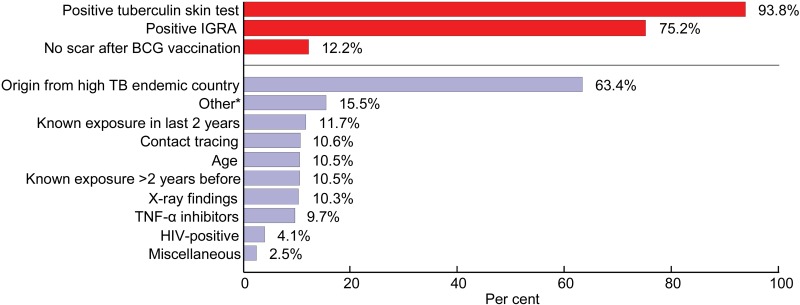

The indications for treatment are shown in Figure 1. The questionnaire that formed the basis for these findings allowed multiple choices, i.e., there was more than one indication for 95% of the patients. A positive tuberculin skin test (TST), a positive interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) and/or originating from a country with high levels of endemic TB were the three main reasons for starting treatment. HIV testing was performed for 36% of the participants before starting treatment; 29 patients (4%) were positive. Sputum samples were collected for culture for 70% of the patients before treatment. Of these, 63% were culture-negative at the time of treatment initiation (Figure 2), while in 36% the culture results were not known ahead of treatment. Of those with an unknown culture result, 5.9% had findings on X-ray.

FIGURE 1.

Reasons for prophylactic TB treatment in Norway in 2009. IGRA= interferon-gamma release assay; BCG = bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccine; TB = tuberculosis; TNF = tumour necrosis factor; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus.

FIGURE 2.

HIV infection tests and sputum culture before start of prophylactic TB treatment in the four health authority regions in Norway in 2009. HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; TB = tuberculosis.

Implementation

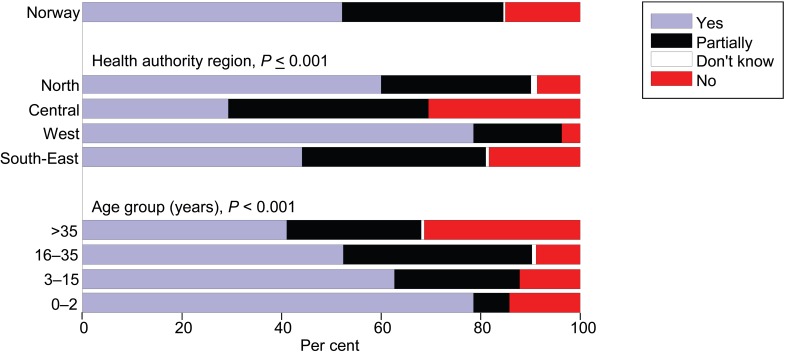

Sixty-seven per cent of the participants had started LTBI treatment within 3 years after arriving in Norway, 36% in <1 year. The preferred treatment regimen for 95% of the participants was 3 months of rifampicin and isoniazid, given once daily. Vitamin B6 was prescribed for 92.5% of the patients. For > 90%, a treatment plan meeting was held and an individual treatment plan was established before treatment. Daily directly observed treatment (DOT) was used for 376 (52%) patients. Only 15% of the overall patient group administered the treatment themselves; the remaining 233 (33%) received partial DOT (Table 1). We observed a significantly different rate of DOT use for different age groups (P < 0.001), regions (P = 0.009) and origins of the patients (P = 0.001; Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Use of directly observed treatment for latent tuberculous infection by health authority region and age group.

Treatment was completed by 607 (84%) patients. The results of the logistic regression are seen in Table 2. Health region and age were significant predictors for completion.

TABLE 2.

Results of the logistic regression analyses of factors with possible influence on completion of treatment for latent tuberculous infection

| Fully adjusted model GOF: P = 0.003 |

Unadjusted model |

GOF P value | Final model GOF: P < 001 |

||||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Health Region | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| South-East | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| West | 0.90 (0.40–2.04) | 0.89 (0.41–1.92) | 0.92 (0.42–2.01) | ||||

| Central | 0.65 (0.28–1.52) | 0.58 (0.26–1.30) | 0.64 (0.28–1.47) | ||||

| North | 0.30 (0.15–0.57) | 0.31 (0.17–0.55) | 0.28 (0.15–0.81) | ||||

| Sex (female) | 1.03 (0.61–1.73) | 0.940 | 1.23 (0.75–2.01) | 0.420 | 0.419 | — | — |

| Age | 0.97 (0.95–0.99) | 0.002 | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.97 (0.96–0.99) | 0.001 |

| Origin | 0.873 | 0.666 | 0.626 | — | |||

| Northern/Western Europe | 1 | 1 | — | ||||

| Southern/Eastern Europe | 1.38 (0.39–4.94) | 1.99 (0.61–6.45) | — | ||||

| South America | 0.55 (0.06–5.12) | 0.91 (0.10–8.08) | — | ||||

| Asia | 0.95 (0.38–2.42) | 1.29 (0.61–2.72) | — | ||||

| Africa | 0.86 (0.34–2.18) | 0.97 (0.48–1.96) | — | ||||

| Treatment strategy | 0.673 | 0.768 | 0.769 | — | |||

| Self-administered | 1 | 1 | — | ||||

| Daily DOT | 0.94 (0.37–2.36) | 1.17 (0.56–2.46) | — | ||||

| Partial DOT | 0.75 (0.31–1.83) | 0.96 (0.44–2.10) | — | ||||

GOF = goodness of fit; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; DOT = directly observed treatment.

Side effects were reported for 199 (28%) patients, and were more common in women (P = 0.04, Table 3). Serious side effects leading to termination of treatment were reported in 50 (7%) cases. The most common side effects were nausea (8%), biochemical signs of hepatotoxicity (7%), headache (4%) and rash (3%).

TABLE 3.

Reported side effects among all patients treated for latent tuberculous infection in Norway in 2009

| Total | Yes n (%) | No n (%) | Don’t know n (%) | P value | |

| Sex | 0.004 | ||||

| Total* | 704 | 199 (28) | 464 (66) | 44 (6) | |

| Male | 346 | 80 (23) | 238 (69) | 28 (8) | |

| Female | 361 | 119 (33) | 226 (62) | 16 (4) | |

| Age, years | 0.005 | ||||

| Total* | 710 | 199 (28) | 466 (66) | 45 (6) | |

| ≤2 | 14 | 1 (7) | 13 (92) | 0 | |

| 3–15 | 115 | 24 (21) | 88 (77) | 3 (3) | |

| 16–35 | 407 | 111 (28) | 268 (66) | 28 (7) | |

| >35 | 174 | 63 (36) | 97 (56) | 14 (8) | |

| Health region | <0.001 | ||||

| Total* | 712 | 199 (28) | 468 (66) | 45 (6) | |

| South-East | 345 | 107 (31) | 224 (65) | 14 (4) | |

| West | 129 | 41 (32) | 85 (65) | 3 (2) | |

| Central | 81 | 18 (22) | 60 (74) | 3 (4) | |

| North | 157 | 33 (21) | 99 (63) | 25 (16) | |

| Time spent in Norway before treatment, years | 0.021 | ||||

| Total* | 711 | 199 (28) | 468 (66) | 44 (6) | |

| <1 | 258 | 55 (21) | 185 (72) | 18 (7) | |

| 1–3 | 222 | 58 (26) | 151 (69) | 13 (6) | |

| 3–5 | 34 | 15 (44) | 18 (53) | 1 (3) | |

| ≥6 | 78 | 31 (40) | 41 (53) | 6 (8) | |

| Born in Norway | 113 | 39 (34) | 69 (61) | 5 (4) | |

| Unknown | 6 | 1 (16) | 4 (67) | 1 (17) |

Total number <721 due to lack of data.

Interviews with the medical specialists

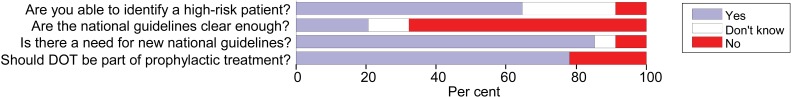

The interviews with the medical specialists showed that chest X-ray, medical history, TST and IGRA were important assessment tools for the diagnosis of LTBI (Figure 1). Seventy six per cent of the specialists had confidence in preventive treatment for LTBI, and 73% believed that treatment should be applied using DOT. Only 20% of the specialists thought that the advice in the current national guidelines was sufficiently clear, and 85% saw a need for revised national guidelines. Sixty four per cent reported that they were able to identify at-risk patients (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Answers from 34 Norwegian tuberculosis specialists to questions about prophylactic therapy for latent tuberculous infection, 2009. DOT = directly observed treatment.

According to the specialists, it appeared that the follow-up of the patient during treatment varied, and in some cases it was different from the current recommendations. The number of specialists interviewed was too small, however, to be able to draw any final conclusions.

The ability self-reported by the specialists to identify at-risk patients was not significantly associated with the perceived need for new national guidelines (P = 0.145) or with the evaluation of the clarity of the TB guidelines (P = 0.544); these last two parameters were significantly associated with each other (P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

This study highlights how LTBI was managed and followed up in Norway in 2009. This is the first study in Norway to document how, why and for whom treatment for LTBI is initiated. The majority of those treated were young adult asylum seekers or immigrants from Africa or Asia (Figure 1), reflecting the composition of the immigrant population in Norway. In 2009, 17200 people applied for asylum in Norway,12 254 (1.5%) of whom received treatment for LTBI. In a cohort study of asylum seekers in Norway in 2005 and 2006, 1% were given LTBI treatment.13

The use of IGRA was implemented in Norway in 2007, with the presumption that this would lead to a reduction in the number of people being referred to a specialist due to a false-positive TST.14 The recommended method for detecting LTBI in Norway is a two-step approach combining TST and IGRA testing.15 If the decision to treat LTBI is based on the result of these diagnostic tools alone, without taking into consideration other risk factors, one may question the benefit of this treatment. Even for a person with a positive TST from a country with a high TB burden, the risk of progression to active TB is low as long as the person does not have any other risk factors and is living in a low-risk country.16 Our data indicate that risk factors other than originating from a country with high endemic levels of TB accounted for only a small proportion of the indications for initiating preventive treatment (Figure 1).

Only 36% of the study participants were tested for HIV before being treated for LTBI. This is disturbing, as HIV-infected persons have a 100 times higher risk of developing TB.17 Studies have documented that LTBI treatment given to HIV-positive persons will reduce the risk of developing active TB by 62–80%, and preventive LTBI treatment among HIV-infected persons is an important part of the TB control strategy worldwide.18–22

In recognition of the risk of starting LTBI treatment in a person with active TB, there is a need for clear recommendations about how to rule out active disease ahead of treatment. In our study, sputum samples for culture were collected from 70% of the participants before treatment, of whom 63% were culture-negative at treatment initiation. These findings suggest a need to improve the diagnostic work-up before treatment initiation, in accordance both with the recommendations of the National Public Health Institute of Norway and with common clinical practice.

Health region and age were significant predictors for completion rate (Table 2). As data were not obtained on the social and financial status of the participants, an evaluation of their impact on treatment adherence was not possible. The Northern Health region had lower completion rates than others; however, we cannot give any exact explanation for this.

Based on our own experience, we assume that preparation of the patient through treatment meetings, information and guidance, close collaboration between health care personnel and close follow-up have contributed to the high treatment completion rate of 84%. Even those who self-administered their treatment had weekly meetings with health care personnel. All these follow-up measures seem to have greater importance than DOT alone, which in the regression analyses (Table 2) was not a significant factor for treatment completion. Other studies have shown completion rates of between 29% and 81%.23,24 Akolo et al. concluded that DOT had no positive effects on completion of preventive therapy compared with self-administration, and suggested the development of programmes providing patients with support and motivation.22 A review article by Hirsch-Moverman et al. in 2008 suggests that there is a need for systematic studies investigating the type of approach that can best improve patient adherence and improve completion rates.25 The implementation of TB coordinators in Norway in 2004, an initiative that aimed to strengthen TB control and improve patient supervision, may have contributed to the high completion rate.

The DOT regimen was criticised by some of our patients for being condescending, and was characterised as having a ‘nanny mentality’. However, this must be weighed against the fact that the effectiveness of LTBI treatment depends on its completion and that DOT also provides care for patients. DOT should be considered and used in special situations, such as when there is poor communication due to language problems, cultural differences or psychosocial problems.

No adverse events requiring hospital admission were reported in this study. The most commonly reported side effects were headache, hepatotoxicity (mainly elevated transaminases), nausea and other gastrointestinal tract symptoms, findings that have also been observed in other studies.6,26 Norwegian guidelines suggest stopping all treatment if serum transaminase levels increase to >3 times the normal rate and if there are symptoms of hepatitis.15

In this study, 76% of all patients receiving LTBI treatment were aged <35 years. Previous Norwegian guidelines advised against treatment of persons aged >35 years,15 and some studies have raised questions about the age-related risk of hepatotoxicity, adverse events and withholding treatment for those aged >35 years. Their findings may indicate that there is a need to focus more on older patients and their co-morbidities than on age alone.27,28

There was a significant association between side effects and age, sex and health region (Table 2). More women than men reported side effects. One study has indicated that sex differences in occurrence of adverse drug events may be related to a range of factors, including biological or psychosocial differences.29 We have no data to explain this difference, but speculate that women may have a lower tolerance of treatment than men, or that they report side effects more often. The benefits of treatment must always be weighed against the disadvantages of side effects. We believe that the threshold for interrupting preventive therapy could and should be lower than that for treatment of active TB.

Although some specialists claimed that they were able to diagnose LTBI and identify those most at risk of progressing to active TB, the key challenge remains to determine which high-risk individuals should receive preventive therapy. This study emphasises the need for clearer recommendations and better tools to perform risk assessment.

Strengths and limitations of the study

The strengths of the study were that all LTBI patients treated in the country were included and that participation of health care staff in the study was high. All TB coordinators contributed with data, which gave us an accurate picture of the situation throughout Norway.

There are some limitations, however. Our study only provides a snapshot of how LTBI was handled at a certain time, but it can serve as a baseline for future studies that evaluate the implementation of new guidelines in Norway. We had no direct access to the patients’ medical files: all information was collected through the questionnaire completed by the TB coordinators, which could represent a potential responder bias.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings indicate that screening, diagnosis and treatment of LTBI in Norway are in accordance with current recommendations. However, the data showed that treatment was mainly offered based on screening results, and for this reason we question whether the right persons were treated, i.e., those at highest risk. We consider that there is potential to improve risk assessments and to focus more on high-risk persons, and tools to perform risk assessment are required. From the specialists’ point of view, the national guidelines in 2009 were relatively vague in their recommendations about who should receive preventive treatment. This vagueness may have influenced the total number of persons treated in 2009. New guidelines and recommendations are wanted and needed.

The use of DOT entails economic and resource-related challenges. There is a need to continuously develop and evaluate interventions to improve treatment adherence that may serve as an alternative or complement to DOT.

Norway is a small country, and it should be possible to achieve uniform practice in handling LTBI.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere thanks to the TB coordinators Tone Louise Skorge and Haldis Kollbotn for their help in the data collection process. They acknowledge all the TB coordinators in Norway for providing patient data and the medical specialists who were interviewed, and they are grateful to Helge Børresen, who double-checked the data set.

This study was partially funded by the Torgersens Foundation and Blakstad & Maarschalk TB Fund.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2012. WHO/HTM/TB/2012.6. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borgen K, Koster B, Meijer H, Kuyvenhoven V, van der Sande M, Cobelens F. Evaluation of a large-scale tuberculosis contact investigation in the Netherlands. Eur Respir J. 2008;32:419–425. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00136607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Antonucci G, Girardi E, Raviglione M C, Ippolito G. Risk factors for tuberculosis in HIV-infected persons. A prospective cohort study. The Gruppo Italiano di Studio Tubercolosi e AIDS (GISTA) JAMA. 1995;274:143–148. doi: 10.1001/jama.274.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Selwyn P A, Hartel D, Lewis V A, et al. A prospective study of the risk of tuberculosis among intravenous drug users with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1989;320:545–550. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198903023200901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nasjonalt Folkehelseinstitutt. Forebygging og kontroll av tuberkulose. Oslo, Norway: Nasjonalt Folkehelseinstitutt; 2002. [Norwegian] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ena J, Valls V. Short-course therapy with rifampin plus isoniazid, compared with standard therapy with isoniazid, for latent tuberculosis infection: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40:670–676. doi: 10.1086/427802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Organ B. Efficacy of various durations of isoniazid preventive therapy for tuberculosis: five years of follow-up in the IUAT trial. International Union Against Tuberculosis Committee on Prophylaxis. Bull World Health Organ. 1982;60:555–564. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langenskiold E, Herrmann F R, Luong B L, Rochat T, Janssens J P. Contact tracing for tuberculosis and treatment for latent infection in a low incidence country. Swiss Med Wkly. 2008;138:78–84. doi: 10.4414/smw.2008.11964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li J, Munsiff S S, Tarantino T, Dorsinville M. Adherence to treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in a clinical population in New York City. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e292–e297. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hess K, Goad J, Wu J, Johnson K. Isoniazid completion rates for latent tuberculosis infection among college students managed by a community pharmacist. J Am Coll Health. 2009;57:553–555. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.5.553-556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lydersen S, Fagerland M, Laake P. Recommended tests for association in 2×2 tables. Stat Med. 2009;28:1159–1175. doi: 10.1002/sim.3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Norwegian Directorate of Immigration. Årsrapport 2009. Tall og fakta [Annual report 2009] Oslo, Norway: UDI; 2009. [Norwegian] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harstad I, Heldal E, Steinshamn S L, Garåsen H, Winje B A, Jacobsen G W. Screening and treatment of latent tuberculosis in a cohort of asylum seekers in Norway. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38:275–282. doi: 10.1177/1403494809353823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lalvani A. Diagnosing tuberculosis infection in the 21st century: new tools to tackle an old enemy. Chest. 2007;131:1898–1906. doi: 10.1378/chest.06-2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nasjonal Folkehelseinstitutt. Forebygging og kontroll av tuberkulose. Oslo, Norway: Nasjonal Folkehelseinstitutt; 2002. [Norwegian] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook V J, Hernández-Garduño E, Elwood R K. Risk of tuberculosis in screened subjects without known risk factors for active disease. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:903–908. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halsey N A, Coberly J S, Desormeaux J, et al. Randomised trial of isoniazid versus rifampicin and pyrazinamide for prevention of tuberculosis in HIV-1 infection. Lancet. 1998;351:786–792. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)06532-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bucher H C, Griffith L E, Guyatt G H, et al. Isoniazid prophylaxis for tuberculosis in HIV infection: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. AIDS. 1999;13:501–507. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199903110-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gordin F, Chaisson R E, Matts J P, et al. Rifampin and pyrazinamide vs isoniazid for prevention of tuberculosis in HIV-infected persons: an international randomized trial. Terry Beirn Community Programs for Clinical Research on AIDS, the Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group, the Pan American Health Organization, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Study Group. JAMA. 2000;283:1445–1450. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.11.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawken M P, Meme H K, Elliott L C, et al. Isoniazid preventive therapy for tuberculosis in HIV-1-infected adults: results of a randomized controlled trial. AIDS. 1997;11:875–882. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199707000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whalen C C, Johnson J L, Okwera A, et al. A trial of three regimens to prevent tuberculosis in Ugandan adults infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Uganda-Case Western Reserve University Research Collaboration. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:801–808. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709183371201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akolo C, Adetifa I, Shepperd S, Volmink J. Treatment of latent tuberculo-sis infection in HIV infected persons. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD000171. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000171.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shieh F K, Snyder G, Horsburgh C R, Bernardo J, Murphy C, Saukkonen J J. Predicting non-completion of treatment for latent tuberculous infection: a prospective survey. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:717–721. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200510-1667OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trajman A, Long R, Zylberberg D, Dion M J, Al-Otaibi B, Menzies D. Factors associated with treatment adherence in a randomised trial of latent tuberculosis infection treatment. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:551–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirsch-Moverman Y, Daftary A, Franks J, Colson P W. Adherence to treatment for latent tuberculosis infection: systematic review of studies in the US and Canada. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:1235–1254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berg J, Blumberg E J, Sipan C L, et al. Somatic complaints and isoniazid (INH) side effects in Latino adolescents with latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) Patient Educ Couns. 2004;52:31–39. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kunst H, Khan K S. Age-related risk of hepatotoxicity in the treatment of latent tuberculosis infection: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:1374–1381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith B M, Schwartzman K, Bartlett G, Menzies D. Adverse events associated with treatment of latent tuberculosis in the general population. CMAJ. 2011;183:E173–179. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nordeng H. Kjønnsforskjeller i forekomst av legemiddelrelaterte bivirkninger [Gender differences in the occurrence of adverse drug events] Nor J Epidemiol (Norsk Epidemiologi) 1999;9:143–148. [Norwegian] [Google Scholar]