Abstract

Setting:

A non-governmental organization, Dignitas International, working in partnership with the Ministry of Health in Malawi, adopted innovative, low-technology methods to collect, capture, and manage patient-level antiretroviral therapy (ART) data in a district database covering 26 remote low-resource facilities in Zomba District, Malawi.

Objective:

To establish a longitudinal, observational database of routinely collected program data that could serve as a program monitoring and evaluation tool as well as a platform to conduct effective operational research.

Design:

This article describes the processes developed for digital capture of paper-based ART clinical records at health facilities and updating them in a central electronic database. It documents and focuses on lessons learned during the implementation and review of processes.

Conclusions:

Data quality can only be ensured with regular review of, and compliance with, clearly delineated workflow protocols and adequate staffing and supervision. Through the implementation of this procedure, we expect to improve data quality, completeness, and use of routine ART clinical data in low-resource settings.

Keywords: low-technology data collection, data quality, monitoring, evaluation

Abstract

Contexte:

Dans le District Zomba au Malawi, une organisation non-gouvernementale, Dignitas International, travaillant en partenariat avec le Ministère de la Santé du Malawi, a adopté des méthodes novatrices d’un faible niveau de technicité pour colliger, recueillir et traiter les données concernant le traitement antirétroviral (ART) au niveau des patients provenant d’une base de données de district couvrant de multiples services éloignés et à faibles ressources.

Objectif:

Etablir une base de données observationnelles longitudinales à partir des données de programmes rassemblées en routine, base qui pourrait servir comme outil de suivi et d’évaluation du programme et comme plateforme pour une recherche opérationnelle efficiente.

Schéma:

Cet article décrit les processus élaborés dans les services de santé pour la capture digitale des dossiers papier cliniques concernant l’ART et pour leur mise à jour dans une base de données électronique centrale. Il se focalise sur les leçons tirées au cours de la mise en œuvre et de la révision des processus et il les documente.

Conclusions:

On ne peut garantir des données de qualité qu’au moyen de révisions régulières des protocoles clairement définis de flux de travail, par l’étude de la conformité à leur égard, et enfin par un personnel et une supervision adéquats. Grâce à la mise en œuvre de cette procédure, nous espérons améliorer la qualité, le caractère complet et l’utilisation des données sur les aspects cliniques de l’ART administrée en routine dans des contextes à faibles ressources.

Abstract

Marco de referencia:

La organización no gubernamental, Dignitas International, en colaboración con el Ministerio de Salud de Malaui, adoptó métodos innovadores de baja tecnología encaminados a capturar, recopilar y gestionar los datos sobre el tratamiento antirretrovírico (ART) a escala del paciente, en una base de datos distrital que cubra múltiples establecimientos de escasos recursos en el distrito de Zomba en Malaui.

Objetivo:

Establecer una base de datos observacional de corte longitudinal, donde se centralicen los datos corrientes recogidos en el marco del programa que pueden servir como instrumento de seguimiento y evaluación, de manera que se puedan utilizar como una plataforma eficaz de investigación operativa.

Método:

Se describe el procedimiento elaborado con el fin de capturar de manera electrónica la información clínica impresa sobre el ART a partir de los expedientes clínicos en los establecimientos de salud y de actualizar esta información en una base de datos central. El tema principal es la documentación de las enseñanzas extraídas durante la ejecución y la evaluación de los procedimientos.

Conclusión:

La única forma de mantener una buena calidad de los datos es establecer protocolos de flujo de trabajo claramente trazados, evaluarlos de manera periódica y vigilar su cumplimiento, además de contar con una plantilla de personal suficiente y una supervisión adecuada. Al introducir estos procedimientos se prevé un mejoramiento en la calidad de los datos y en su carácter integral y una mejor utilización de la información clínica corriente sobre el ART en los entornos con escasos recursos.

With the recent scale-up of antiretroviral treatment (ART) services in sub-Saharan Africa, there is a great need for quality and accessible patient-level data to evaluate the effectiveness of these programs. Treatment outcomes, loss to follow-up and adherence need to be measured at patient level to identify default and survival rates. In many government and non-governmental organizations, routine data collection for ART programs involves the manual aggregation of clinical patient data and registers by clinic staff on a monthly or quarterly basis that is then shared with donors, ministries, and other stakeholders.1 A recent study conducted by an international collaborative human immunodeficiency virus research network found that many sites had a high percentage of errors even in these key variables, notably laboratory data, weight measurements, ART regimens and associated dates, largely due to errors in extraction and missing source documents.2 The reliability of such data may affect true estimates of patient outcomes and program effectiveness.

Operational research, the assessment of strategies in program performance for the purpose of improving local health programs, as adopted by the World Health Organization and the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, is necessary in remote, rural, low-resource settings where outcomes of health programs may not be adequately addressed.3,4 For example, the national ART program in Malawi currently relies largely on manual aggregation of patient data from paper-based ART clinical records and monthly registers for its monitoring and evaluation strategy. However, the large patient volumes (and patient data) and decentralization of care make it difficult to use its paper-based system for monitoring patient-level outcomes. Electronic medical record systems have been tested in Malawi and have had positive results in improving patient-level data collection and quality.5 However, these point-of-care systems require technological resources and highly trained staff to manage the systems. As a result they need expensive and ongoing financial support. At many primary health care centers in Malawi, this is not feasible.

Dignitas International, a Canadian-based non-governmental organization working in partnership with the Ministry of Health (MoH) in Malawi, adopted inventive low-technology methods to collect, capture, and maintain a district database using Microsoft Access® (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) for patient-level ART data covering 26 remote facilities in Zomba District, Malawi. The goal of this initiative was to establish a district-wide longitudinal, observational database of routinely collected patient-level data that could be used as a program monitoring tool and to conduct effective operational research.6,7 This article first describes the processes developed for digitally capturing ART clinical records at health facilities and updating them in a central database. It then focuses on lessons learned as the processes were implemented and reviewed in an effort to ensure and improve the quality and completeness of the data.

METHODS

Primary paper-based records are generated by health care providers at primary care health facilities providing ART services. The ART clinical record, a nationally standardized document (the ART master card) that contains the clinical information for each patient and is updated on paper at every patient encounter by health care providers, is kept at the health facility.

Various methods to capture the paper ART master card in digital format were considered, including regularly moving the paper records to a central location for data entry or photocopying the master cards, but these options were discarded: health care providers require the clinical record to remain at the health facility for patient care, and photocopying would require a copying machine with a portable power supply, which would be costly and cumbersome. A field digitization and central data capture system was developed as a more feasible alternative.

At the beginning of each month, three data digitizers and a driver visit each of the primary health care facilities that provide ART in Zomba District. The team of data digitizers is equipped with two digital cameras, locally produced camera stands, charged batteries, empty data cards, a barcode scanner and a laptop. At the health facility, the data digitizers identify the staff in charge, typically a nurse or a clinical officer, and request access to the patient master cards. If they are unable to provide access to the master cards, the team leaves for the next facility and returns on another day. Permission to access and collect patient data was provided in advance by the MoH Zomba District Health Office.

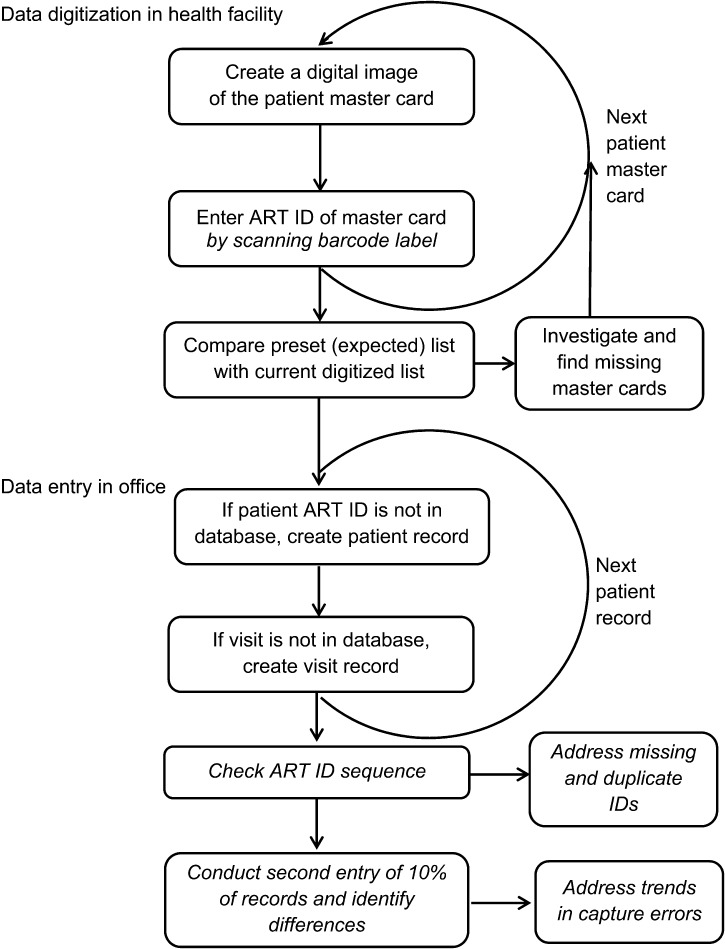

The whole team, including the driver, participates in pairs in the digitizing process (Figure). At each facility, the active patient master cards are filed in binders labeled in sequential numerical order of the program identification codes (ART IDs). Master cards for patients who have died or are lost to follow-up are kept in a separate binder. The team takes the binders to an empty room in the facility to be digitized. A photo with the name of the facility and the binder label is taken at the start of the digitizing process as a way of demarcation. After each card is photographed, the patient ART ID from each card is entered into a file tracking tool created for the process in Microsoft Access®. In some facilities the files are labeled with barcodes that can be scanned directly into the file tracking tool. Otherwise they are entered manually. Once entered, the file tracking tool is able to query the database to identify file numbers scanned in previous months but missing from the current round. The team can then follow up with health center staff to try and clarify the status of these patients and their files.

FIGURE.

Monthly ART data digitization and data entry workflow. Tasks in italics added after reviewing process. ART = antiretroviral therapy; ID = identification.

After the facility’s master cards have been digitized, the team moves on to the next facility. Approximately three to four facilities are visited each day. At the end of each day, the digitized files are backed up onto a server, after which data entry staff extract the data from the images to update the records in the main database. Data entry and validation are concurrent with the digitization process. Data are entered once, and a randomly selected number of cards are checked routinely for accuracy of data entry. Each month, 2 working weeks are required to visit and digitize all active master cards in the district. For example, in the first 2 weeks of June 2012, 12115 ART cards were digitized at 26 primary health care centers in Zomba District. The file tracking tool is updated before the next month of digitization visits.

Observations (lessons learned)

A thorough review of the quality and completeness of data captured in the database using the process outlined above raised significant concerns. Structured observations as well as consultations with data digitizers, data entry and other data management staff were undertaken to explore challenges in the digitization and maintenance processes, and suggestions for improvement were made. The Table outlines the observed challenges and suggestions. The Figure gives an overview of the data collection and data entry processes that were reviewed by the team.

TABLE.

Lessons learned from digitally capturing ART clinical records at health facilities and updating them in a central database

| Observed challenges | Means for improvement |

| 1 Data digitization | Modified data collection procedures |

| • Hastily performed tasks and photography, including inconsistent use of the camera stands or not removing master cards from their protective transparent plastic folder, producing poor image quality and illegibility and causing data entry gaps and errors | • Use fast, duplex sheetfed scanners (with autonomous power) instead of digital cameras, ensuring good image quality and complete (multipage) record scans |

| • Lack of systematic logging of digitized master cards, and systematic checking for missing master cards during digitizing | • Use barcoded labels (a sticker with ART ID in barcode and standard characters) on all plastic folders (each holds the master cards of one patient). Generate a list of digitized master cards, using a barcode scanner, and use the list to update a file tracking tool. Identify non-digitized records and take action before leaving the facility |

| • Missing records not always communicated with facility’s care providers who may be able to provide further information | • Before leaving the facility, communicate and investigate data gaps or errors with the facility’s care providers to make corrections where possible and identify patients that need tracing |

| • Digital image files not named and filed systematically, resulting in near impossibility to find an image to crosscheck information in the whole patient record | • Rename each electronic image file with predetermined structure; ART ID (health facility code and serial number) and digitizing year and month, and save in predetermined electronic folders |

| 2 Quality control | Implement quality control measures |

| • Lack of systematic checking of the ART ID sequence to identify missing IDs (assigned to no patient) and duplicate IDs (assigned to multiple patients) | • Systematic (monthly for each facility) use of the ‘ART ID sequence check tool’ to identify misformated, missing or duplicate ART IDs and address errors promptly |

| • Exclusive focus on digitization of most recent master cards (latest patient visits, recorded on one side of the master card), prohibiting a full record history review | • In addition to monthly digitization of most recent master cards, perform periodic (annual) full file scans (all master cards for one individual recorded over time) to ensure data completeness |

| • Lack of control of data entry accuracy | • Systematic double entry of 10% of randomly selected records. Review trends in errors made and address these with individual data entry clerks |

| • Lack of systematic and regular supervision of data collection, management, and entry | • Regular on-site supervision of collection processes for tracking users and regular review of data entry patterns and issues between senior data staff and data teams |

| 3 Health system record keeping | Facilitate health systems record management |

| • Providers at health facilities not maintaining paper records in systematic fashion, introducing complications to the digitizing processes | • Have data team log issues found in reviewing paper records for communication back to health facility staff and Ministry of Health supervision teams |

| • Patients move between facilities, temporarily receiving ART from a different facility from where their master card is kept. Those visits are not recorded, creating apparent missing or defaulted patients | • Introduce log sheets for transient patients at all facilities. This should facilitate the recording of patient ART ID and information collected for one patient visit, equivalent to one row on the ART card. These log sheets need to be digitized each month, the data updated in the database and the original ART facility informed |

| 4 Under-resourced data management team | Ensure adequate human resources |

| • Pressure to complete tasks in time by too few data collectors and data entry clerks, resulting in compromised quality | • Adequate human resources for data collection, data entry and validation |

| • Inadequate supervision as a result of too few senior data staff, resulting in compromised quality assurance monitoring | • Adequate supervisory staff is key to ensuring regular review of processes to ensure quality and complete data |

| • Main focus on having all sites digitized and captured in time versus completeness and quality of data | • Introduce performance-based incentives to encourage optimal data collection, capture and quality control |

| 5 Inadequate use of data and feedback | Improve capacity and communication |

| • Limited attention and capacity of ART program managers to use collected data and give feedback about data issues needing attention | • Capacity building among ART program managers to allow them to use the data more regularly in order to identify clinically relevant issues and provide meaningful feedback |

| • Limited understanding among the data team about how data are used to inform care delivery | • Capacity building among data teams in the role of high quality data in improving quality of care |

| • Limited feedback to health facility staff about the results of the data collected and how they are being utilized | • Regular provision of reports and findings generated from data provided to both data teams and health facilities, with opportunity for feedback |

ART = antiretroviral therapy; ID = identification.

Five major challenges were identified: poor data digitization, including inefficient file storage; lack of quality control; health systems challenges; an under-resourced data team; and inadequate use of data and feedback.

1 Data digitization

Understaffing and time pressure favored quantity over quality. Hastily performed tasks during data digitization resulted in poor image quality, causing data gaps and errors. Only the most recent patient visits were digitized, with staff assuming that previous entries had been correctly captured in earlier visits. The file tracking tool was not consistently utilized, and as a result follow-up with health facility staff on missing records was not done. Communication with care providers about data gaps or errors is essential for corrections to be made, and to identify patients who have defaulted from care and need tracing. Technical solutions were identified, including barcoded labels for individual patients to simplify file tracking and utilization of duplex scanners to improve image quality and completeness. However, these will only improve data capture if handled with adequate staffing and consistent and careful utilization.

The way digital images were filed during digitization made it impossible to find specific patient records for record verification. Renaming and saving each electronic image file with a predetermined structure that includes patient identification codes and date will enable improved data updating, verification and cleaning.

2 Quality control

Data digitizers and data entry staff did not review or ensure the completeness and quality of the data. Data were infrequently checked for missing information and were rarely followed up on, and data entry accuracy was not assessed. Systematic checking for misformated, missing or duplicate ART IDs and promptly addressing errors is essential to ensure completeness of data. In addition to monthly digitization of the most recent patient ART cards, annual complete file scans (all ART cards for one patient over time) are required to ensure data completeness. Double data entry of a percentage of records could assess the level of accuracy of data entry staff and the validity of the data.

More supervision and training should be provided for data collectors and data entry staff on quality assurance. This should then be followed up with regular, onsite assessment and review of processes and results to allow issues to be identified.

3 Health systems

Providers at health facilities do not always maintain and file patient ART cards systematically. This introduces complications in the digitizing process. In addition, patients who move between facilities for care are often not adequately tracked and may be listed as lost to follow-up in the database. A solution for this is to implement log sheets or registers at all health facilities to record transient patient IDs. These sheets or registers will then need to be digitized each month along with the ART cards and the information used to update patient record data. Improved communication between data digitization teams and MoH supervision teams about problems detected and continual reinforcement of proper procedures will be needed to address these issues.

4 Human resources and supervision

Understaffing and lack of supervision compromised data quality and quality assurance. Hiring and training additional staff to meet the resource capacity requirements will improve the quality of data only if adequate supervision and systematic use of quality assurance tools and processes are also implemented. The introduction of performance-based incentives for data digitizers and data entry personnel may be a means of further improving data quality.

5 Data use and feedback

There was limited utilization of the data by medical program managers. Program managers should be given the skills to use the data provided by the patient-level database proficiently to report and explore clinical and program questions, and they should give feedback on the data themselves. In addition, data teams have little understanding of how the data they are collecting are used, and health facility staff receive almost no feedback on the data collected from their sites. It is critical to develop means for the reports and the findings generated from the data to be shared with those responsible for collecting them.

DISCUSSION

Paper-based data collection systems are inefficient in settings where a large number of patients are enrolled in long-term follow-up care, and considerable amounts of clinical data accumulate, leading to difficulties in data management and analysis. While electronic capture of data from primary care health facilities is becoming increasingly common through different technologies, the need for supervision and data quality assurance is essential for any data to be usable. In Zomba District, Malawi, the sheer number of patients receiving ART care, coupled with the low-resource context, renders most technologies inefficient or expensive. For example, in a study to examine the use of personal digital assistants (PDAs) in data collection from 11 sites in Tanzania, Maokola et al. found that PDAs do not alleviate the issues of poor data quality and completeness.8 In Zomba, where Dignitas International and the MoH support ART service delivery at 26 primary health care facilities, a centralized database with patient information has the potential to greatly improve aggregated reporting by elimination of human counting errors, improved systemic organization of patient files and increased utilization of patient data for monitoring and evaluation and operational research. With the development of a central database containing all patient data from the entire district, updated on a regular basis, we hope to stimulate increased data use by stakeholders, identify gaps in service delivery, and initiate improvements in a more timely manner. In addition, ongoing regular monthly contact with all patient master cards can result in increased dialogue between data digitizers and health care workers and help in identifying missing files or data. Capacity building through training and proper supervision for all staff members who handle data, including program managers, implementers, and data entry staff, can improve the quality of data and increase the use of collected data in a meaningful way.9

The data collection and management method described in this article has obvious benefits in collecting and capturing data in resource-limited rural settings. In areas where primary health care facilities do not have the resources to adopt sophisticated electronic medical systems, digitization is a relatively simple, efficient, and accurate method to obtain routine patient-level data in a format that can be analyzed and updated. Unlike electronic medical record systems, only basic and inexpensive technology is required, such as digital cameras or scanners and data cards. The methods and processes are applicable to other types of facility data, and although only ART treatment cards are discussed in this article, the process can and is applied to other health data, including monthly registers, other program treatment cards, and monthly reports. There is great potential to improve ART monitoring and evaluation practices by identifying the movement of patients between health facilities and loss to follow-up in a more efficient manner with electronic capture and management of these data.

Based on our experience, we have documented lessons learned and identified improvements that can be made to the process of data digitization. Overall, clear standard operating procedures for digitization, data entry and file management are essential. These must be coupled with human supervision on their use and consistent quality assurance processes that assess data integrity. The data digitization approach will allow ongoing review of patient-level and aggregated facility-level data to assess the effectiveness of ART programs in rural, remote, low-resource settings, and bring further adaptation for improvement through more effective operational research.

CONCLUSION

The digitization process described in this article is an innovative, low-technology solution for collecting patient-level data from remote health facilities. However, data quality can only be ensured with adequate staffing and supervision, in addition to regular review and compliance with workflow protocols. Future directions that may be undertaken include increased quality assurance training for health facility staff and data management staff, a cost-benefit analysis of this approach, and a formal quality improvement process to both enhance and evaluate our approach.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Zomba District Health Management team for their continuous support and the Dignitas digitizing and data management team for their diligence. This article has been produced with the financial assistance of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union). The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the positions of The Union.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Hedt-Gauthier B L, Tenthani L, Mitchell S, et al. Improving data quality and supervision of antiretroviral therapy sites in Malawi: an application of Lot Quality Assurance Sampling. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:196. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duda S N, Shepherd B E, Gadd C S, Masys D R, McGowan C C. Measuring the quality of observational study data in an international HIV research network. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e33908. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harries A D, Rusen I D, Reid T, et al. The Union and Médecins Sans Frontières approach to operational research. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:144–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Implementation research for the control of infectious diseases of poverty. Geneva, Switzerland: UNICEF/UNDP/World Bank/WHO; 2011. http://www.who.int/tdr/publications/documents/access_report.pdf Accessed April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waters E, Rafter J, Douglas G P, Bwanali M, Jazayeri D, Fraser H S. Experience implementing a point-of-care electronic medical record system for primary care in Malawi. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2010;160:96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forum for Collaborative HIV Research. HIV cohorts and databases. Washington DC, USA: Forum for Collaborative HIV Research; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Loggerenberg F, Mlisana K, Williamson C, et al. Establishing a cohort at high risk of HIV infection in South Africa: challenges and experiences of the CAPRISA 002 Acute Infection Study. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1954. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maokola W, Willey B A, Shirima K, et al. Enhancing the routine health information system in rural southern Tanzania: successes, challenges and lessons learned. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:721–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mphatswe W, Mate K S, Bennett B, et al. Improving public health information: a data quality intervention in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2012;90:176–182. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.092759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]