Abstract

Setting:

All designated microscopy centres (DMCs) in Fatehgarh Sahib District, Punjab, India.

Objective:

To study the association of distance (physical access) to DMCs with loss to follow-up (LTFU) of presumptive tuberculosis (TB) cases while undergoing diagnostic sputum examination and failure to initiate treatment among smear-positive TB patients after diagnosis.

Design:

A cross-sectional, record-based study was undertaken to analyse patient records from routine laboratory registers in all DMCs from January to June 2012.

Result:

More than 50% of presumptive TB cases had to travel >7 km to reach the DMC, totalling >28 km for two sputum examinations for the evaluation of an episode. The distance (>10 km) to the diagnostic facility was found to be significantly associated (P < 0.01), both with LTFU during diagnosis and with a delay (>7 days) in initiating treatment after diagnosis. There was a significant correlation (r = 0.7) between distance to the DMC and time to initiate treatment among smear-positive TB cases.

Conclusion:

Distance from the nearest facility represents a significant risk for LTFU during diagnosis and delayed initiation of treatment after diagnosis. Further decentralisation of TB care services to the community level is required by expanding the network of DMCs or by organising sputum collection and transportation.

Keywords: TB diagnosis, physical access, India, RNTCP

Abstract

Contexte:

Tous les Centres de Microscopie Attitrés (DMC) dans le District de Fatchgarth Sahib, au Punjab.

Objectif:

Etudier l’association entre la distance (accès physique) au DMC et la perte de suivi (LTFU) de cas avec une tuberculose (TB) présumée en cours d’examen des crachats à visée diagnostique ainsi que l’absence de mise en route du traitement parmi les patients TB à frottis positif après ce diagnostic.

Schéma:

On a entrepris une étude transversale basée sur les dossiers et analysé les dossiers des patients à partir des registres de routine du laboratoire dans tous les DMC de janvier à juin 2012.

Résultat:

Plus de 50% des cas de TB présumée devaient se déplacer de >7 km pour atteindre le DMC, ce qui conduit à un total de >28 km pour deux examens de crachats au cours de l’évaluation d’un épisode. La distance (>10 km) vers le service de diagnostic est en association significative (P < 0,01) à la fois avec le LFTU au cours du diagnostic et avec la durée (>7 jours) avant la mise en route du traitement après ce diagnostic. On a noté une corrélation significative (r = 0,7) entre la distance jusqu’au DMC et le nombre de jours avant la mise en route du traitement dans les cas de TB à frottis positif.

Conclusion:

Une longue distance jusqu’au service le plus proche constitue un risque plus grand de LTFU au cours du diagnostic ainsi qu’un risque de mise en route retardée du traitement après le diagno-stic, ce qui pousse à une décentralisation complémentaire des services de soins TB vers le niveau de la collectivité grâce à l’expansion du réseau de DMC ou grâce à l’organisation de la collecte des crachats et de leur transport.

Abstract

Marco de referencia:

Todos los centros designados de microscopia (DMC) en el distrito Fatehgarh Sahib del Punjab.

Objetivo:

Estudiar la asociación que existe entre la distancia hasta el DMC, las pérdidas durante el seguimiento (LTFU) de los casos con presunción diagnóstica de tuberculosis (TB) en la fase del estudio microscópico del esputo y la falta de iniciación del tratamiento antituberculoso en los pacientes con baciloscopia positiva una vez establecido el diagnóstico.

Métodos:

Fue este un estudio transversal realizado a partir de los datos de los pacientes consignados sistemáticamente en el laboratorio, en todos los DMC entre enero y junio del 2012.

Resultados:

Más de 50% de los pacientes con presunción diagnóstica de TB tenía que recorrer más de 7 km con el fin de llegar al centro de microscopia, es decir un trayecto >28 km para dos baciloscopias durante la investigación de un episodio. Se observó que la distancia al centro diagnóstico (>10 km) se asociaba de manera significativa (P < 0,01) con la LTFU antes de establecer el diagnóstico y también con un retraso del comienzo del tratamiento después de haberlo establecido (>7 días). Se encontró una correlación significativa entre la distancia al DMC y el número de días necesarios hasta el comienzo del tratamiento en los casos de TB con baciloscopia positiva (r = 0,7).

Conclusión:

Una distancia importante hasta el DMC más cercano constituye un gran riesgo de LTFU en la fase diagnóstica y también de retraso del comienzo del tratamiento antituberculoso después de haber establecido el diagnóstico. Esta situación exige una mayor descentralización de los servicios de atención de la TB hacia el nivel comunitario, mediante la ampliación de la red de DMC y la organización de la recogida y el transporte de las muestras de esputo.

The Government of India’s Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP) has established designated microscopy centres (DMCs) to provide free, quality-assured sputum smear microscopy services for the diagnosis of tuberculosis (TB). There are about 13 000 DMCs across the country, an average of one per 100 000 population.

Individuals with TB symptoms visit the DMCs to undergo sputum smear microscopy. The DMCs are not easily accessible, and many people have to travel long distances to access the services, incurring huge direct and indirect costs.1 Previous studies have shown that increasing distance from health services inhibits the use of primary2 and secondary care,3 thereby leading to poor health outcomes. Some studies have shown that poor access to TB services leads to delayed health seeking, thereby delaying diagnosis and treatment.4 These studies have used proxy indicators such as place of residence, presence of health care providers in the village and the need to use transport to reach health care facilities to measure access to health care.

Providing decentralised TB diagnostic services and ensuring universal access to TB care is an important mandate of the RNTCP.5 However, to our knowledge, no studies have assessed whether there is a relationship between distance from the patients’ residence to the DMC and losses during diagnosis or delayed initiation of treatment.

An operational research study was undertaken in Fatehgarh Sahib District in the State of Punjab, North India, to assess the association between distance to the DMC and 1) loss of presumptive TB cases during the diagnostic process, and 2) failure to initiate treatment among smear-positive TB patients after diagnosis. The study also assessed whether demographic factors such as age and sex were associated with losses during or after diagnosis for smear-positive TB cases, and whether there was any correlation between time to treatment initiation and distance to the DMC.

METHODOLOGY

Study setting

Fatehgarh Sahib (population 600 000; area 1147 km2 ), a rural district in Punjab, India, has a reasonably good health infrastructure with 2 primary health centres, 11 mini primary health centres, 3 community health centres and 26 subsidiary health centres. The district also has 72 subcentres, 2 rural hospitals, 1 district hospital, 1 civil dispensary and 1 sub-divisional hospital and several private nursing homes. There are six DMCs, all located within public health facilities. The villages are well connected by road. Presumptive TB cases are referred by local practitioners, peripheral health institutions and health workers to a DMC for sputum testing. Each presumptive TB case is required to submit two sputum samples, one spot and one early morning, often on 2 separate days. People with at least one of the two sputum specimens positive for acid-fast bacilli using Ziehl-Neelsen staining are diagnosed as having sputum smear-positive pulmonary TB.

Laboratory registers maintained at each DMC contain information such as laboratory serial number, date of sputum examination, name, age, sex, address, name of the referring health facility, whether the person is undergoing smear microscopy for diagnostic purposes and microscopy results. Details of patients initiated on treatment (including date of start of treatment) are also entered in the laboratory register.

Study design

This was a cross-sectional, observational study in which patient records from routine laboratory registers in all six DMCs in the district were analysed for the period January–June 2012.

Study variables, source of information and definitions

The study variables included all the above-mentioned information obtained from the laboratory register. Loss to follow-up (LTFU) during diagnosis was defined as a presumptive TB case who failed to submit two sputum samples at any DMC in the district and whose first sputum was negative. If the patient submitted only one positive sputum sample this was not considered LTFU. TB laboratory registers were reviewed to assess whether the smear-positive TB patient had initiated treatment and the date of starting treatment. Treatment initiation was calculated from the time the first positive result was available. Patients not initiated on treatment within 28 days of diagnosis were defined as initial LTFU.

The distance of the DMC from the patients’ residence was calculated using the distance measure-ment tool available in Google Maps (Google, Mountain View, CA, USA, http://maps.google.co.in/). The shortest road distance indicated by the software, measured in km rounded to 1 decimal point, was recorded. The distance was also independently validated with the local health workers and, in case of disagreement (i.e., if the difference was >5 km), study investigators visited both the DMC and the village to assess the distance.

Study population

The study population included all presumptive TB cases who underwent sputum smear microscopy for diagnosis in the six DMCs in Fatehgarh Sahib District of Punjab during the period January–June 2012. All smear-positive TB patients were assessed for treatment initiation. Presumptive TB cases whose addresses were not recorded in the register or who could not be located on Google Maps, and those whose residential address was not in the district, were excluded.

Data entry and analysis

Dual data entry was performed using EpiData 3.1 statistical software (EpiData Association, Odense, Denmark), corrected and analysed. Distance between DMC and place of residence was evaluated as a binary variable of ≤10 km and >10 km, a distance that was considered as a measure of reasonable access. Participants in both groups (≤10 and >10 km) were compared for both LTFU during diagnosis and initial LTFU. Qualitative variables were summarised as proportions, and χ2 test and risk ratios (with 95% confidence limits) were used to compare the groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

The study was reviewed and approved by the District TB officer and Civil Surgeon of the District of Fatehgarh Sahib, the Ethics Advisory Group of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease and the Institutional Ethics Committee of PGIMER, Chandigarh.

RESULTS

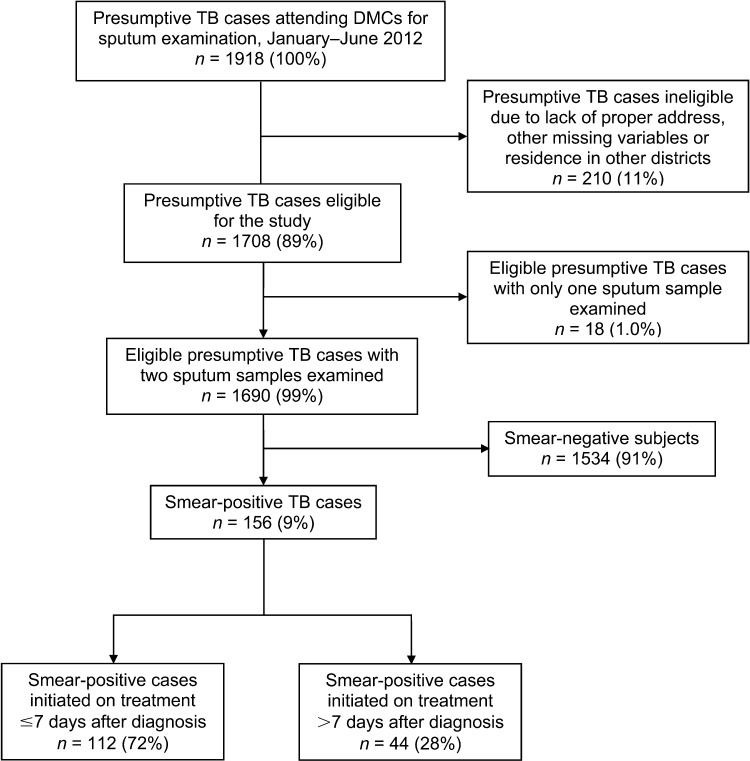

Of 1918 presumptive TB cases registered during January–June 2012, 1708 (89%) patient records fulfilled the eligibility criteria and were included in the study. Among those eligible, 18 (1%) were LTFU during diagnosis. Of those who underwent two sputum smear examinations, 156 (9%) were smear-positive. All smear-positive TB patients were started on treatment, 44 (28%) of these >7 days after diagnosis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart showing presumptive TB cases attending DMCs in the District of Fatehgarh Sahib, Punjab, India, January–June 2012. TB = tuberculosis; DMC = designated microscopy centre.

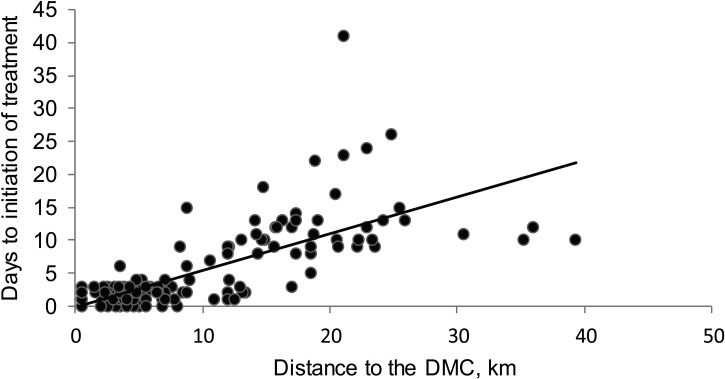

Disagreement between measures of distance using Google Maps and validation by health workers was less than 2%. The median distance travelled by presumptive TB cases in the district to reach the DMC was 6.9 km (interquartile range 3.5–12.9). About 36% (n = 619) of the presumptive TB cases travelled >10 km; more of these were females (P < 0.05). Distance of >10 km to the diagnostic facility was found to be significantly associated with both LTFU during diagnosis and >7 days to initiation of treatment after diagnosis among smear-positive cases (P < 0.01, Table). However, there was no significant association of age and sex with LTFU during diagnosis. Neither age nor sex had any significant association with days to initiation of treatment after diagnosis among smear-positive TB patients. There was a significant correlation (r = 0.7) between distance to the DMC and the number of days before initiating treatment among smear-positive TB cases (Figure 2).

TABLE.

Association of various variables with distance to the DMC in Fatehgarh Sahib, Punjab, India, January–June 2012

| Characteristic | Total n (%) | Distance ≤10 km n (%) | Distance >10 km n (%) | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Total | 1708 (100) | 1089 (100) | 619 (100) | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 944 (55) | 624 (57) | 320 (52) | 1.2 (1.0–1.3) | 0.02 |

| Female | 764 (45) | 465 (43) | 299 (48) | ||

| Age, years | |||||

| <15 | 66 (4) | 46 (4) | 20 (3) | — | 0.59 |

| 15–60 | 1346 (79) | 856 (79) | 490 (79) | ||

| >60 | 296 (17) | 187 (17) | 109 (18) | ||

| Reason for examination | |||||

| Initial diagnosis | 1404 (82) | 882 (81) | 522 (84) | 0.9 (0.7–1.0) | 0.08 |

| Repeat examination | 304 (18) | 207 (19) | 97 (16) | ||

| LTFU during diagnosis | |||||

| Yes | 18 (1) | 5 (1) | 13 (2) | 2.0 (1.5–2.7) | 0.001 |

| No | 1690 (99) | 1084 (99) | 606 (98) | ||

| Treatment initiation among smear-positive TB cases, days | (n = 156) | (n = 103) | (n = 53) | ||

| ≤7 | 112 (72) | 101 (98) | 11 (21) | 9.7 (5.5–17.1) | <0.001 |

| >7 | 44 (28) | 2 (2) | 42 (79) |

DMC = designated microscopy centre; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; LTFU = loss to follow-up.

FIGURE 2.

Correlation between distance to DMC and number of days to initiation of treatment in Fatehgarh Sahib, Punjab, India, January–June 2012. DMC = designated microscopy centre.

DISCUSSION

This is one of the few studies conducted under routine programme settings in India to study a large sample of presumptive TB cases for the association of access to a DMC with both LTFU during diagnosis and delays in treatment initiation after diagnosis. While previous studies used proxy indicators to measure access,6–9 this is one of the first studies to use web-based technology for direct measurement of distance to assess physical access.

The study has several implications. First, it shows that >50% of presumptive TB cases had to travel >7 km, often on 2 separate days, to reach the DMC, totalling >28 km for two sputum examinations for the evaluation of one episode. Second, the study shows that when patients had to travel >10 km, there was a significant association with LTFU and delay in initiation of treatment >7 days, which is similar to previous studies.10,11 The need to travel long distances could present a deterrent to seeking care. Furthermore, there could be several social and economic implications to travelling long distances, such as travel time, travel cost and disruption of routine activities.12 LTFU during diagnosis and delayed treatment initiation could result in undiagnosed/untreated TB, resulting in continued transmission of the disease in the community. These findings highlight the importance of bringing TB services closer to patients’ homes, either by expanding the network of DMCs or by organising sputum collection and transportation.

Third, significantly more females travelled >10 km to seek TB care (P < 0.05), the reasons for which need more exploration. Fourth, only 1% of the eligible persons with presumptive TB were LTFU during diagnosis, and all smear-positive TB patients were initiated on treatment. This is in contrast to reports from other settings in the country, where initial LTFU has been in the range of 5–10%.13,14 This may be attributed to the rigorous monitoring mechanism and effective follow-up of presumptive TB cases and newly diagnosed patients in the district. However, it could also be due to the exclusion criteria used for the study, as those whose address was not recorded and those who belonged to other districts were not included. This might influence the results, as these patients were deemed to be staying in the district temporarily and more likely to be LTFU.

Finally, a worrying finding was that nearly 28% of smear-positive TB cases were initiated on treatment >7 days after diagnosis, which is similar to the findings in another study by Paul et al. in two districts of India.9 The number of days needed to initiate treatment also increased with increase in the distance of the patient’s residence from the DMC, which could be attributed to delays in the transportation of drugs, probably due to the large geographical distances. This problem could be resolved by decentralising drug stocks or by issuing initial treatment doses to patients at the point of diagnosis to minimise any delays in initiating treatment.9

Limitations

There are three limitations to this study. First, the data were taken from programme records and the distance was measured using web-based technology. Any deficiencies in these two systems could affect study findings. However, discrepancies in Google Maps measurements were validated by the investigator himself in the field. Second, only patients who accessed services from RNTCP DMCs were included in the study. We are therefore unable to provide information about patients who visited private or other care providers. Furthermore, presumptive cases who were referred for diagnosis but who failed to attend the DMC were not accounted for. Finally, the geographic distance from the patient’s residence to the DMC may not always correspond to travel time. For example, travel time using a poor quality road or across difficult terrain may be longer, even where the physical distance is less.

CONCLUSION

Long distance (>10 km) to the nearest facility poses a risk for LTFU during diagnosis and delayed initiation of treatment after diagnosis. This could be addressed by further decentralisation of TB diagnostic services to the community level.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the technical support and constant motivation received from Prof R Kumar, School of Public Health, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India.

This research was supported through an Operational Research course jointly developed and run by the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, South-East Asia Regional Office, New Delhi; the National Institute for Research in Tuberculosis, Chennai, India; and the Desmond Tutu TB Centre, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa. Funding for the Operational Research course was made possible by the support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis or interpretation of data. The contents of this article do not necessarily reflect the views of the USAID or the Government of the United States.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Laokri S, Drabo M K, Weil O, et al. Patients are paying too much for tuberculosis: a direct cost-burden evaluation in Burkina Faso. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e56752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones A P, Bentham G, Harrison B D, et al. Accessibility and health service utilization for asthma in Norfolk, England. J Public Health Med. 1998;20:312–317. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a024774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haynes R, Bentham C G, Lovett A, Gale S. Effects of distances to hospital and GP surgery on hospital in-patient episodes, controlling for needs and provision. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:425–433. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Storla D G, Yimer S, Bjune G A. A systematic review of delay in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sachdeva K S, Kumar A, Dewan P, Kumar A, Satyanarayana S. New vision for Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme (RNTCP): universal access—‘Reaching the un-reached’. Indian J Med Res. 2012;135:690–694. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wondimu T, Michael K W, Kassahun W, Getachew S. Delay in initiating tuberculosis treatment and factors associated among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in East Wollega, western Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2007;21:148–156. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tamhane A, Ambe G, Vermund S H, Kohler C L, Karande A, Sathiakumar N. Pulmonary tuberculosis in Mumbai, India: factors responsible for patient and treatment delays. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:569–580. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belay M, Bjune G, Ameni G, Abebe F. Diagnostic and treatment delay among tuberculosis patients in Afar Region, Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:369. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paul D, Busireddy A, Nagaraja S B, et al. Factors associated with delays in treatment initiation after tuberculosis diagnosis in two districts of India. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e39040. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajeswari R, Chandrasekaran V, Suhadev M, Sivasubramaniam S, Sudha G, Renu G. Factors associated with patient and health system delays in the diagnosis of tuberculosis in South India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2002;6:789–795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shargie E B, Lindtjorn B. Determinants of treatment adherence among smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients in southern Ethiopia. PLOS Med. 2007;4:e37. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buor D. Analysing the primacy of distance in the utilization of health services in the Ahafo-Ano South District, Ghana. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2003;18:293–311. doi: 10.1002/hpm.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sai Babu B, Satyanarayana A V V, Venkateshwaralu G, et al. Initial default among diagnosed sputum smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Andhra Pradesh, India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:1055–1058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Government of India. Tuberculosis India 2012. Annual report of the Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme. New Delhi, Delhi: Central Tuberculosis Division Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India; 2012. [Google Scholar]