Abstract

Setting:

In 2008, the Kenya tuberculosis (TB) program reported low (31%) antiretroviral therapy (ART) uptake among human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infected TB patients.

Objective:

To confirm ART coverage and identify factors associated with HIV clinic enrollment and ART initiation among TB patients.

Design:

Retrospective chart abstraction of adult TB patients newly diagnosed with HIV and eligible for ART at 58 Nyanza Province TB clinics between October 2006 and April 2008. TB data were linked to HIV clinic data at 50 facilities that provided ART. Associations with HIV clinic enrollment and ART were evaluated.

Results:

Among 1137 ART-eligible TB patient records sampled, 32% documented HIV clinic enrollment and 29% ART. Date fields were largely incomplete; 11% of the patient records included HIV testing dates and ≤1% had dates for cotrimoxazole prophylaxis, HIV clinic enrollment and ART initiation. Adding HIV clinic data increased HIV clinic enrollment and ART documentation to respectively 62% and 44%. Among TB patients in HIV care, female sex, older age group and baseline CD4 documentation were associated with ART initiation.

Conclusion:

Linking data increased documentation of HIV clinic enrollment and ART uptake. Continued efforts are required to improve the documentation of HIV service delivery, especially in TB clinics. Interventions to increase ART uptake are needed for younger patients and men.

Keywords: ART-eligible, TB clinics, HIV clinics

Abstract

Contexte:

En 2008, le programme de tuberculose (TB) du Kenya a signalé une piètre utilisation du traitement antirétroviral (ART) chez les patients TB infectés par le virus de l’immunodéficience humaine (VIH).

Objectif:

Confirmer la couverture par l’ART et identifier les facteurs associés avec l’enregistrement dans un dispensaire VIH et la mise en route de l’ART chez les patients TB.

Schéma:

Etude rétrospective des dossiers des patients TB adultes récemment diagnostiqués comme séropositifs pour le VIH et éligibles pour l’ART dans 58 dispensaires TB de la Province de Nyanza entre octobre 2006 et avril 2008. Les données TB ont été liées aux données des dispensaires VIH dans les 50 services qui assurent l’ART. On a évalué les associations avec l’enregistrement dans les dispensaires VIH et l’ART.

Résultats:

Sur les 1137 dossiers de patients TB éligibles pour l’ART qui ont été échantillonnés, 32% ont signalé un enrôlement dans un dispensaire VIH et 29% l’ART. Les données concernant les dates sont fort incomplètes ; 11% des dossiers de patients ont inclus les dates de tests VIH et ≤1% les dates de la prophylaxie au cotrimoxazole, de l’enrôlement dans les dispensaires VIH et de la mise en route de l’ART. L’ajout des données cliniques VIH a augmenté l’enrôlement dans les dispensaires VIH et la documentation sur l’ART jusqu’à respectivement 62% et 44%. Parmi les patients TB soignés pour le VIH, la mise en route de l’ART est en association avec le genre féminin, les groupes d’âge plus avancé et les CD4 initiaux.

Conclusion:

Le croisement des données a augmenté les informations sur l’enrôlement dans les dispensaires VIH et sur la mise en route de l’ART. Il est nécessaire de poursuivre des efforts pour améliorer les informations sur la fourniture de service VIH, particulièrement dans les dispensaires TB. Des interventions visant à l’extension de l’ART sont nécessaires chez les patients plus jeunes et chez les hommes.

Abstract

Marco de referencia:

En el 2008, el Programa contra la Tuberculosis en Kenia notificó una baja (31%) utilización del tratamiento antirretrovírico (ART) en los pacientes infectados por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH) y aquejados de tuberculosis (TB).

Objetivo:

Confirmar la cobertura del ART y definir los factores que se asocian con la inscripción al consultorio de atención del VIH y la iniciación del ART en los pacientes con diagnóstico de TB.

Métodos:

Se llevó a cabo un análisis retrospectivo de las historias clínicas de los pacientes adultos con TB y diagnóstico reciente de VIH, que cumplían con los requisitos del ART en 58 consultorios de TB de la provincia de Nyanza de octubre del 2006 a abril del 2008. Se vincularon los datos de la consulta de TB con los datos de la consulta del VIH de 50 establecimientos que suministraban el ART. Se evaluaron luego las asociaciones con la inscripción al consultorio del VIH y el inicio del ART.

Resultados:

En la muestra de expedientes clínicos de 1137 pacientes TB aptos al ART se documentó un 32% de inscripción al consultorio de la infección por el VIH y 29% de iniciación del programa ART. Los datos en el terreno eran en gran medida incompletos; 11% de las historias clínicas contaba con la fecha de la prueba del VIH y 1% o menos contenía la fecha de la profilaxis con la asociación de trimetoprim y sulfametoxazol (cotrimoxazol), la inscripción al consultorio del VIH y la iniciación del ART. Cuando se agregaron los datos del consultorio del VIH, aumentó la cifra de inscripción a esta consulta a 62% y la información sobre el ART a 44%. En los pacientes con TB inscritos al consultorio del VIH, los factores que se asociaron con el comienzo del ART fueron el sexo femenino, el grupo de mayor edad y la información sobre el recuento inicial de células CD4.

Conclusión:

La vinculación de los datos mejoró la documentación sobre la inscripción al consultorio del VIH y la utilización del ART. Se precisan iniciativas sostenidas que mejoren la documentación sobre la prestación de atención a la infección por el VIH, sobre todo en los consultorios de TB. Es necesario contar con intervenciones que aumenten el recurso al ART por parte de los pacientes más jóvenes y los hombres.

In 2008, 1.4 million of the 9.4 million global new tuberculosis (TB) cases were co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV); sub-Saharan Africa contributed 30% of the new TB cases and 79% of the HIV-infected TB cases.1 In 2004, the World Health Organization (WHO) released its ‘Interim policy on collaborative TB/HIV activities’, recommending HIV testing for all TB patients and provision of cotrimoxazole preventive therapy (CPT) and antiretroviral therapy (ART) for eligible HIV-infected TB patients according to individual country guidelines.2 As of 2008, 23% of TB patients globally knew their HIV status (53% in Africa); 71% of those co-infected had initiated CPT (76% in Africa) and 32% had initiated ART (36% in Africa).1

Kenya, which is characterized by 6.3% adult HIV prevalence (2008–2009)3 and a TB case notification rate of 329 per 100 000 population,4 is severely affected by the TB-HIV syndemic, and initiated implementation of the WHO-recommended TB-HIV collaborative activities in 2005.5,6 Remarkable progress was made, and by 2008, 91 508 (83%) of the 110 251 annual TB cases had undergone HIV testing; 40 167 (44%) were HIV-positive and 37 757 (94%) received CPT.1,4 However, ART coverage lagged among all co-infected patients, at 31%.1,4

Nyanza Province, in western Kenya, has the country’s highest HIV prevalence (13.9% adult HIV prevalence),3 and a TB case notification rate of 402/100 000.4 In 2008, the provincial TB program successfully provided HIV testing to 77% of TB patients and CPT to 98% of co-infected patients.7 However, the provincial program remained challenged by a 31% ART uptake among all co-infected patients.7 It was unclear if this low ART uptake was due to poor documentation and/or communication between TB and HIV clinical services. We sought to confirm the proportion of patients receiving ART at facilities offering both TB and ART services—by linking patient records from TB and HIV clinics, and those offering anti-tuberculosis treatment-only services—and to identify factors associated with HIV clinic enrollment and ART uptake among newly HIV-diagnosed ART-eligible TB patients.

METHODS

Setting and study sample

In 2007, 289 Nyanza health facilities offered anti-tuberculosis treatment services; 109 (38%) facilities also provided ART services for >1 year at on-site separate HIV clinics (TB-ART facilities). Fifty TB-ART facilities were selected for patient chart abstraction, consisting of forced inclusion of the 1 provincial and all 16 district hospitals, and 33 lower-level facilities (health centers and dispensaries) using probability proportionate to size (PPS) sampling weighted by the 2007 TB patient volume. We calculated that a sample size of 1000 would allow estimation of ART uptake among HIV co-infected TB patients with a precision of 5%, assuming a cumulative loss to follow-up/transfer/death rate of 10% and a design effect of 1.5. Another eight facilities were selected from the 180 facilities providing TB treatment only, using PPS sampling. These 58 facilities accounted for 58% of Nyanza registered TB patients.

The inclusion criteria included adult TB patients aged ≥15 years registered for anti-tuberculosis treatment between October 2006 and April 2008, newly diagnosed with HIV (defined as date of HIV diagnosis ≤90 days before the initiation of anti-tuberculosis treatment, at TB diagnosis or during anti-tuberculosis treatment) and eligible for ART. ART eligibility criteria followed the 2007 Kenya Ministry of Health guidelines: an HIV-infected TB patient in the intensive or continuation phase of TB treatment with 1) extra-pulmonary TB (EPTB), or 2) pulmonary TB (PTB) with CD4 ≤350 cells/mm3 or unknown, or 3) WHO stage IV disease.

Patients listed in a facility’s TB register were considered for study inclusion. At each selected facility, a chronologic list of eligible HIV-infected TB patients was compiled, and a random number was assigned to each patient using a random number generator. The first 20 numbered patient records were identified and abstracted. For missing/ineligible patient records, the record of the next eligible patient was abstracted to maintain the target sample size. At sites with <20 eligible available patient records, all records were abstracted.

Data collection, management and analysis

A medical record abstraction form (TELEforms; Cardiff Software, Vista, CA, USA) was used to collect demographic and clinical information from TB clinic registers and patient files. At TB-ART facilities, we used patient identifiers (name, date of birth, enrollment age and residential information) to manually link patients to their HIV clinic records in the same facility. Abstracted TB clinic data were confirmed or modified by additional information obtained from HIV clinic registers/records for linked patients. Abstracted data were verified at site for completeness and accuracy. Once the records were linked, patient identifiers were destroyed, and abstraction forms were scanned, validated and stored in a secure password-protected database. None of the records from TB treatment-only facilities were linked to HIV clinic records.

For patients with missing TB treatment initiation date, we used the TB clinic registration date as a proxy. To determine the date of HIV diagnosis for study eligibility, we used the earliest of the following dates: HIV test date, date of HIV clinic enrollment, date of ART initiation or date of CD4 count. As in Kenya patients were enrolled in HIV care before CD4 testing or ART initiation, HIV care enrollment was defined as documentation of an HIV clinic identification number, date of HIV clinic enrollment, baseline CD4 count or receipt of ART. A baseline CD4 count was defined as a CD4 count measured ≤90 days before or during anti-tuberculosis treatment, and ≤30 days following ART initiation. TB patients originally categorized as ART-eligible based on PTB with unknown CD4 and whose subsequent HIV clinic data yielded CD4 counts of >350 cells/mm3 were still considered ART-eligible.

Frequencies, percentages, medians and ranges were used to summarize the data. Unadjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to describe associations. Multivariable logistic regression was used to model HIV clinic enrollment and ART uptake, initially including variables identified in bivariable analysis with P ≤ 0.20, then retaining those that were significant (P ≤ 0.05), with forced inclusion of health facility HIV testing coverage. All analyses were conducted taking into account stratification by sampling structure, clustering by health facility and weighted by inverse probability of facility/participant inclusion. Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (Statistical Analysis Software Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Ethics approval

Study ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of the Kenya Medical Research Institute, Kisumu, Kenya, and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA.

RESULTS

Study sites

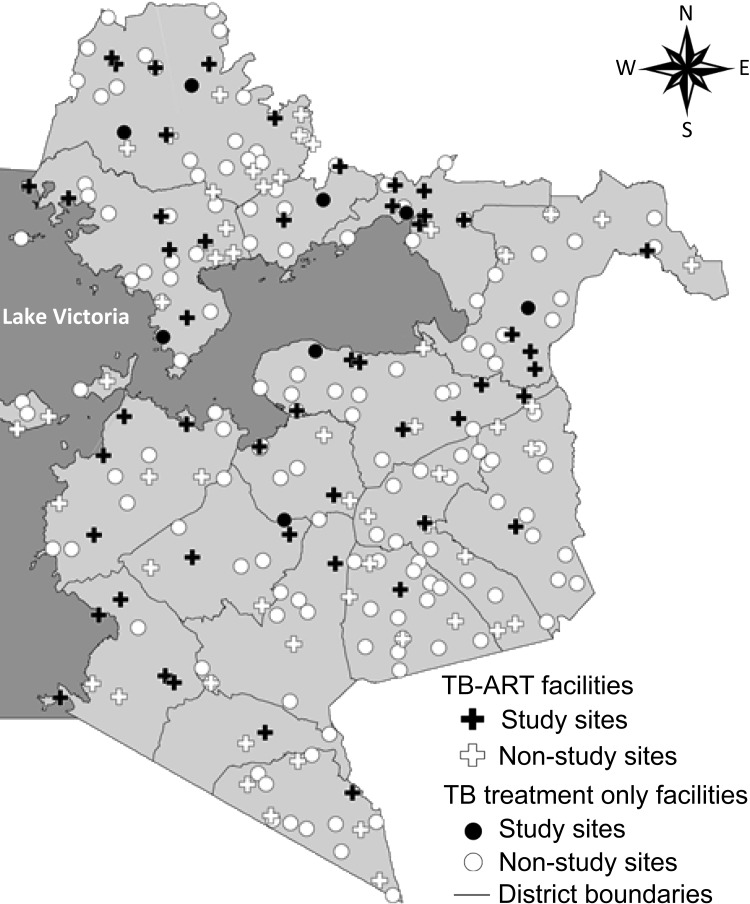

The 58 study health facilities were distributed throughout the province (Figure 1). Few facilities were selected from the far south region, as this area reported lower TB case notification rates and thus had smaller annual TB patient volumes. Between October 2006 and April 2008, these facilities registered 17 245 TB patients; the median number of TB patients per facility was 216 (range 36–943). Overall, 13 698 (79%) TB patients reported HIV status and 10 224 (75%) were HIV-infected. Site median HIV testing coverage of TB patients was 81% (range 28–98%); site median HIV prevalence among patients tested was 77% (range 37–96%). Only two facilities (dispensaries) had <50% HIV testing coverage. No significant associations were observed between the scope of services offered (TB-ART vs. anti-tuberculosis treatment only) or level of facility with HIV testing coverage or HIV prevalence (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

TB treatment sites by facility type, Nyanza Province.

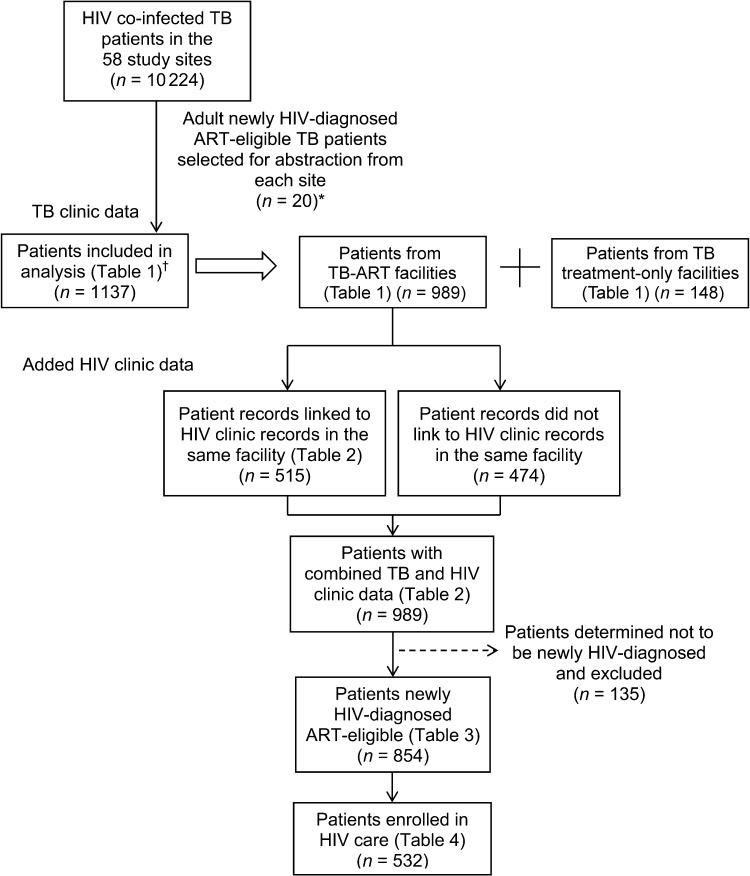

TB clinic data

A total of 1139 TB patient charts were abstracted; two facilities had <20 eligible patients (n = 11 and 8) and all their records were abstracted. We subsequently analyzed 1137 records (two records were omitted when the patient’s age was determined to be <15 years; Figure 2); 989 (87%) patient records were from TB-ART facilities and 148 (13%) from TB treatment-only facilities (Table 1). The patients’ median age was 32 years; 617 (52%) were female. The majority of the patients (n = 916, 82%) were diagnosed with PTB; 43% were sputum smear-positive. The median CD4 count was 117 cells/mm3 (range 2–789), but only 36 (3%) patients had their CD4 count documented; 889 (80%) patients met the ART eligibility criteria for PTB with unknown CD4 count, 221 (18%) had EPTB and only 27 (2%) had PTB with CD4 counts of ≤350 cells/mm3. Although 959 (83%) charts had documentation of CPT receipt, only 379 (32%) indicated HIV clinic enrollment and 334 indicated ART initiation (29%, 95%CI 23.1–35.7; resulting in a design effect of 5.43). Most data fields requiring dates were missing; the HIV testing date was the most complete, at 11%, and ≤1% of patient records had dates for CPT initiation, HIV clinic enrollment, and ART initiation. Patients at TB-ART facilities were more likely to have documentation of HIV care enrollment and ART receipt and were less likely to be diagnosed with EPTB compared to TB treatment-only facilities; however, these differences were not significant.

FIGURE 2.

Schema of newly HIV-diagnosed ART-eligible adult TB patients. * 56 sites had >20 patients and 1120 records were selected from these sites. The remaining two sites had <20 patients and all records (n = 19) were selected. † Two records were omitted when the patient’s age was determined to be <15 years. HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; TB = tuberculosis; ART = antiretroviral therapy.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of newly HIV-diagnosed ART-eligible TB patients

| n (%) | TB/ART facilities n (%) | TB treatment-only facilities n (%) | P value | |||||

| Total number of patients | 1137 | 989 (87) | 148 (13) | |||||

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age, years, median [range] | 32 [15–80] | 32 [15–77] | 31 [15–80] | 0.16 | ||||

| Female | 617 (52) | 531 (51) | 86 (58) | 0.02 | ||||

| TB characteristics | ||||||||

| Type of TB | ||||||||

| PTB | 916 (82) | 809 (83) | 107 (72) | 0.15 | ||||

| EPTB | 210 (17) | 172 (16) | 38 (26) | |||||

| PTB and EPTB | 11 (1) | 8 (1) | 3 (2) | |||||

| Sputum smear results for PTB | (n = 916) | (n = 809) | (n = 107) | |||||

| Sputum-positive | 397 (43) | 349 (43) | 48 (45) | |||||

| Sputum-negative | 353 (39) | 317 (40) | 36 (34) | 0.69 | ||||

| Unknown | 166 (18) | 143 (17) | 23 (21) | |||||

| Type of patient | ||||||||

| New TB diagnosis | 1032 (90) | 896 (90) | 136 (92) | 0.85 | ||||

| TB retreatment | 99 (9) | 88 (9) | 11 (7) | |||||

| Unknown | 6 (1) | 5 (1) | 1 (1) | |||||

| TB treatment outcome | ||||||||

| Successful treatment | 729 (61) | 634 (61) | 95 (64) | 0.98* | ||||

| Failed treatment | 6 (1) | 6 (1) | 0 | |||||

| Died | 82 (8) | 69 (8) | 13 (9) | |||||

| Lost to follow-up | 121 (11) | 105 (11) | 16 (11) | |||||

| Transferred care | 61 (5) | 54 (5) | 7 (5) | |||||

| Unknown | 138 (14) | 121 (14) | 17 (11) | |||||

| HIV characteristics | ||||||||

| Date of HIV testing available | 128 (11) | 119 (12) | 9 (6) | 0.35 | ||||

| Baseline CD4 documented | 36 (3) | 34 (4) | 2 (1) | 0.22 | ||||

| ART eligibility criteria | ||||||||

| PTB with unknown CD4 count | 889 (80) | 784 (81) | 105 (71) | 0.06 | ||||

| EPTB | 221 (18) | 180 (17) | 41 (28) | |||||

| PTB with CD4 ≤350 cells/mm3 | 27 (2) | 25 (2) | 2 (1) | |||||

| Receipt of CPT | 959 (83) | 829 (82) | 130 (88) | 0.21 | ||||

| HIV clinic enrollment | ||||||||

| Enrolled | 379 (32) | 345 (34) | 34 (23) | 0.17 | ||||

| Not enrolled | 758 (68) | 644 (66) | 114 (77) | |||||

| Receipt of ART | 334 (29) | 300 (30) | 34 (23) | 0.40 | ||||

For P value computation, patients who failed treatment and died were merged into one group.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; ART = antiretroviral therapy; TB = tuberculosis; PTB = pulmonary TB; EPTB = extra-pulmonary TB; CPT = cotrimoxazole preventive therapy.

HIV clinic data

Of 989 patients from TB-ART facilities (45% of 1137 TB patients), 515 (52%) were linked to HIV clinic patient records at the same facility (Figure 2). The addition of patients’ HIV clinic data substantially increased the proportion of patients documented to have received HIV services and documentation completeness (Table 2). When TB clinic and HIV clinic data were combined, the proportion of patients with baseline CD4 count data increased to 33%. Documentation of enrollment in HIV care, CPT and ART receipt increased to respectively 67%, 90% and 46%. Dates of HIV testing, CPT initiation, HIV clinic enrollment and ART initiation all increased to >25%. ART eligibility classifications shifted as the number of patients with PTB and unknown CD4 declined, and 13 patients were identified with CD4 counts of >350 cells/mm3. Adding HIV clinic data to the overall 1137 TB patients increased the number of patients with documentation of enrollment to 701 (62%), and those with documentation of ART to 495 (44%, 95%CI 36.7–50.0).

TABLE 2.

Contribution of HIV clinic data to TB clinic data for HIV-infected TB patients at TB-ART facilities

| TB clinic data n (%) | HIV clinic data n (%) | Combined TB and HIV clinic data n (%) | ||||

| Total number of patients | 989 | 515 | 989 | |||

| Date of HIV testing | 119 (12) | 368 (69) | 449 (44) | |||

| WHO stage | 277 (52) | 277 (27) | ||||

| Baseline CD4 cell count, cells/mm3 | ||||||

| Available | 34 (4) | 328 (63) | 344 (33) | |||

| Median [range] | 115 [2–789] | 115 [1–1324] | 118 [1–1324] | |||

| Receipt of CPT | 829 (82) | 474 (91) | 897 (90) | |||

| Date initiated CPT | 19 (1) | 449 (85) | 458 (44) | |||

| HIV clinic enrollment | 345 (34) | 515 (100) | 667 (67) | |||

| Date of HIV clinic enrollment | 7 (1) | 515 (100) | 515 (51) | |||

| ART eligibility classification | ||||||

| PTB with unknown CD4 count | 784 (81) | — | 535 (54) | |||

| EPTB | 180 (17) | 180 (18) | ||||

| PTB with CD4 ≤350 cells/mm3 | 25 (2) | — | 261 (26) | |||

| PTB with CD4 >350 cells/mm3 | — | 13 (2) | 13 (1) | |||

| Receipt of ART | 300 (30) | 296 (57) | 461 (46) | |||

| Date of ART initiation | 5 (0.6) | 288 (54) | 288 (28) | |||

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; TB = tuberculosis; ART = antiretroviral therapy; WHO = World Health Organization; CPT = cotrimoxazole preventive therapy; PTB = pulmonary TB; EPTB = extra-pulmonary TB.

As a result of the improved date documentation, 135 (14%) of the 989 patients initially classified as newly HIV-diagnosed in TB-ART facilities were determined to have been diagnosed >90 days before TB treatment initiation; these patients were excluded from further analysis (Figure 2). Additional analysis on the 854 newly diagnosed ART-eligible TB patients showed that although 62% (532) had HIV clinic documentation indicating enrollment in HIV care, only 274 (50%) of these had HIV care enrollment noted in their TB records. HIV care enrollment was only slightly higher (65%) among 540 TB patients who successfully completed their anti-tuberculosis treatment. Although only 354 (41%) of the 854 patients were documented as receiving ART, this proportion increased to 66% when restricting the analysis to the 532 patients enrolled in HIV care; only 233 (66%) of the 354 patients on ART had ART receipt noted in their TB records.

No demographic or clinical factors were associated with HIV clinic enrollment (Table 3). In bivariable analysis, older age, female sex and having documentation of baseline CD4 count were significantly associated with ART initiation and remained independently associated with ART uptake in multivariable analysis (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Associations of HIV clinic enrollment among newly HIV-diagnosed ART-eligible TB patients from TB-ART facilities

| (n = 854) | Enrolled (n = 532) n (%) | Bivariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

| Unadjusted OR (95%CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | P value | |||

| Facility factors | ||||||

| Facility HIV testing coverage, % | ||||||

| ≤80 | 317 | 192 (60) | Reference | 0.64 | Reference | 0.62 |

| >80 | 537 | 340 (62) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | ||

| Patient factors | ||||||

| Age, years | ||||||

| ≤30 | 372 | 231 (61) | Reference | Reference | 0.70 | |

| >30 | 482 | 301 (62) | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 0.91 | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 416 | 254 (60) | Reference | 0.40 | Reference | 0.37 |

| Female | 438 | 278 (64) | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | ||

| Type of TB* | ||||||

| PTB | 701 | 423 (60) | Reference | 0.09 | ||

| EPTB† | 153 | 109 (69) | 1.5 (0.9–2.4) | |||

| Type of patient | ||||||

| New TB diagnosis‡ | 793 | 494 (61) | Reference | 0.61 | ||

| TB retreatment | 61 | 38 (64) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | |||

| TB treatment outcome | ||||||

| Successful treatment | 540 | 349 | Reference | |||

| Failed treatment | 6 | 5 | 2.2 (0.2–20.4) | 0.16 | ||

| Died | 65 | 34 | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) | |||

| Lost to follow-up | 95 | 63 | 1.0 (0.5–1.9) | |||

| Transferred care | 48 | 25 | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) | |||

| Unknown | 100 | 56 | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | |||

Included in multivariable analysis as in bivariable analysis (P < 0.20), but dropped in the final multivariable model (P > 0.05).

Includes 8 patients with both PTB and EPTB.

Includes 3 patients for whom data on previous TB disease were missing.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; ART = antiretroviral therapy; TB = tuberculosis; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; PTB = pulmonary TB; EPTB = extra-pulmonary TB.

TABLE 4.

Associations of ART uptake among newly HIV-diagnosed ART-eligible TB patients enrolled in HIV care from TB-ART facilities

| (n = 532) | Initiated ART (n = 354) n (%) | Bivariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | |||

| Unadjusted OR (95%CI) | P value | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | P value | |||

| Facility factors | ||||||

| Facility HIV testing coverage, % | ||||||

| ≤80 | 192 | 118 (62) | Reference | 0.43 | Reference | 0.30 |

| >80 | 340 | 236 (68) | 1.3 (0.7–2.7) | 1.5 (0.7–3.1) | ||

| Patient factors | ||||||

| Age, years | ||||||

| ≤30 | 231 | 138 (57) | Reference | <0.01 | Reference | <0.01 |

| >30 | 301 | 216 (73) | 2.1 (1.4–3.1) | 2.7 (1.7–4.4) | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 254 | 156 (62) | Reference | 0.04 | Reference | <0.01 |

| Female | 278 | 198 (71) | 1.5 (1.0–2.3) | 2.4 (1.6–3.7) | ||

| Type of TB | ||||||

| PTB | 423 | 276 (65) | Reference | 0.33 | ||

| EPTB* | 109 | 78 (73) | 1.5 (0.7–3.4) | |||

| Type of patient | ||||||

| New TB diagnosis† | 494 | 325 (65) | Reference | 0.33 | ||

| TB retreatment | 38 | 29 (76) | 1.7 (0.6–4.7) | |||

| TB treatment outcome‡ | ||||||

| Successful treatment | 349 | 244 (70) | Reference | 0.14 | ||

| Failed treatment | 5 | 4 (75) | 1.3 (0.1–13.5) | |||

| Died | 34 | 17 (52) | 0.5 (0.2–0.9) | |||

| Lost to follow up | 63 | 38 (61) | 0.7 (0.3–1.5) | |||

| Transferred care | 25 | 20 (69) | 0.9 (0.3–3.1) | |||

| Unknown | 56 | 31 (58) | 0.5 (0.3–1.1) | |||

| Baseline CD4 documentation | ||||||

| Not documented | 285 | 159 (58) | Reference | <0.01 | Reference | <0.01 |

| Documented | 247 | 195 (76) | 2.3 (1.4–3.7) | 2.6 (1.7–4.1) | ||

Includes 5 patients with both PTB and EPTB.

Includes 3 patients for whom data were missing about previous TB disease.

Included in multivariable analysis as in bivariable analysis (P < 0.20), but dropped in the final multivariable model (P > 0.05).

ART = antiretroviral therapy; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; TB = tuberculosis; OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; PTB = pulmonary TB; EPTB = extra-pulmonary TB.

DISCUSSION

Through linkage of TB and HIV patient records, our study identified deficiencies in documentation of HIV services received by newly HIV-diagnosed ART-eligible TB patients. Fifty per cent of patients enrolled in HIV care and 33% of patients receiving ART had no documentation of these services in their TB records. After linking HIV records to TB records, the completeness of the HIV data improved, and the proportion of all co-infected TB patients documented as having initiated ART increased from 29% to 44%. However, 38% of the co-infected TB patients were not enrolled in HIV care and 34% of those who were enrolled did not initiate ART. Other studies have shown comparable ART uptake levels and identified various patient, facility and health system factors associated with poor ART uptake among HIV-infected TB patients.8–13

Kenyan TB providers documented HIV status and CPT receipt for a high proportion of patients, most likely because this information or service was available or provided during initial patient registration. Our findings indicate that a high proportion of data was missing for HIV services obtained outside the TB clinic either before or after TB registration, due to a lack of referral systems and/or patient/provider information feedback loops.

Our finding that there was no statistical difference in HIV care enrolment at TB-ART vs. TB treatment-only facilities suggests that even facilities with both TB and ART services on-site had poor referral/information feedback systems. Furthermore, even optimal TB patient circumstances had disappointing outcomes; among the 63% of patients who successfully completed anti-tuberculosis treatment at TB-ART facilities (i.e., had good adherence to TB medication and follow-up visits), 35% failed to enroll in HIV care, possibly due to lack of referral, stigma or other factors. Studies have suggested that TB-HIV integration models relying on referral systems have a risk of losing patients and information along the way,14 while ‘one stop’ models (i.e., TB-HIV services provided by one provider) have demonstrated a ≥60% increase in ART uptake.15,16

Although only 62% of TB records documented HIV care enrollment for co-infected patients, we did not find any demographic or clinical characteristics associated with enrollment. This lack of association may be unique to TB clinic settings where patients are relatively equally divided by sex and share similar poor health status compared to other large clinic-based populations. However, once enrolled in HIV care, only 66% of patients initiated ART despite attending facilities that provided both TB and ART services with sufficient stocks of antiretrovirals. Consistent with findings from other studies, men and younger patients were significantly less likely to initiate ART.11,17 Surprisingly, although Kenya’s national criteria did not require CD4 testing among TB patients to initiate ART, patients with CD4 results were three times more likely to initiate ART. Absence of CD4 results is a well-known barrier to ART initiation8,18–20 in settings that rely on CD4 counts to determine ART eligibility. However, for Kenyan sites, this suggests that clinicians may have lacked adequate knowledge or skills.

Our study had three main limitations. First, the sampling design and weighted analysis were based on facility TB patient volume as a proxy for HIV-infected TB patients, as TB clinic HIV prevalence data were unavailable. As HIV testing coverage and HIV prevalence varied by facility, this may have impacted the PPS sampling by misclassifying sites. However, by forcing inclusion of the 17 high-volume hospitals and not detecting significant differences in facility HIV testing coverage and prevalence, site misclassification is likely to minimally impact our findings. Second, we may have missed patients who linked to HIV services. However, we assumed that these numbers are small, as we matched patients based on three identifiers; also, TB patients usually select the TB treatment site closest to their residence, and co-infected patients would likely do the same for HIV services. Third, we assumed that the majority of co-infected patients would be newly HIV diagnosed and ART-eligible. However, based on our findings and other studies,21–23 as ∼30% of patients were HIV-diagnosed >3 months before their TB diagnosis and ∼10% were not yet ART-eligible, the true overall ART coverage for all adult ART-eligible TB patients during this period in our study would have been ∼50%.

In 2010, Kenya implemented new guidelines based on WHO recommendations,24 recommending that all HIV-infected TB patients receive ART, irrespective of CD4 count.25,26 Coupled with providing ART within TB clinics,27 national and Nyanza Province ART coverage among all co-infected TB patients increased to respectively 69% and 62% in 2011.28,29 However, global ART coverage remained <50%.30 Program emphasis on routine data feedback and completeness, and periodic assessments of TB records, may be necessary to identify and improve data quality issues.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the health care workers in Kenya who tirelessly provide TB and HIV services. They acknowledge the Kenya National TB Program, National AIDS and STI Control Program and the Ministry of Health, Nairobi, for their continued guidance in provision of TB and HIV services and their collaboration in this study; the Kenya Medical Research Institute and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA, USA, for their scientific monitoring; and the President’s Emer-gency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), Washington DC, USA, for funding the study.

Data were partially presented at the 41st Union World Conference on Lung Health, 11–15 November 2010, Berlin, Germany, abstract number 0101104: Eligibility and antiretroviral uptake among newly diagnosed adults HIV-infected TB patients, Kenya.

This publication was made possible by support from the US PEPFAR through cooperative agreement number 5U19CI000323 from the Division of Global HIV/AIDS, US CDC.

The findings and conclusions in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of PEPFAR, the US CDC or the Government of Kenya.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Global tuberculosis control, 2009 report. WHO/HTM/TB/2009.411. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Interim policy on collaborative TB/HIV activities. WHO/HTM/TB/2004.330, WHO/HTM/HIV/2004.1. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kenya National Bureau of Statistics and ICF Macro . Kenya demographic and health survey 2008–09. Nairobi, Kenya: KNBS & ICF Macro; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kenya Division of Leprosy Tuberculosis and Lung Disease . Annual report. Nairobi, Kenya: Kenya Ministry of Health, 2009; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization . A brief history of tuberculosis control in Kenya. WHO/HTM/TB/2008.398. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kenya Division of Leprosy Tuberculosis and Lung Disease . Guidelines for implementing TB-HIV collaborative activities in Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya: Ministry of Health; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kenya Division of Leprosy Tuberculosis and Lung Disease Nyanza Province TB-HIV Program surveillance data. Kisumu, Kenya: Ministry of Health. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okot-Chono R, Mugisha F, Adatu F, Madraa E, Dlodlo R, Fujiwara P. Health system barriers affecting the implementation of collaborative TB-HIV services in Uganda. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:955–961. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chileshe M, Bond V A. Barriers and outcomes: TB patients co-infected with HIV accessing antiretroviral therapy in rural Zambia. AIDS Care. 2010;22:51–59. doi: 10.1080/09540121003617372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris J B, Hatwiinda S M, Randels K M, et al. Early lessons from the integration of tuberculosis and HIV services in primary care centers in Lusaka, Zambia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12:773–779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumwenda M, Tom S, Chan A K, et al. Reasons for accepting or refusing HIV services among tuberculosis patients at a TB-HIV integration clinic in Malawi. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:1663–1668. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong K, Thabethe Z, Hurtado R, et al. Challenges to the success of HIV and tuberculosis care and treatment in the public health sector in South Africa. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(Suppl 3):S491–S496. doi: 10.1086/521111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pevzner E S, Vandebriel G, Lowrance D W, Gasana M, Finlay A. Evaluation of the rapid scale-up of collaborative TB-HIV activities in TB facilities in Rwanda, 2005–2009. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:550. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Legido-Quigley H, Khan C M M P, Atun R, Fakoya A, Getahun H, Grant A D. Integrating tuberculosis and HIV services in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2013;18:199–211. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huerga H, Spillane H, Guerrero W, Odongo A, Varaine F. Impact of introducing human immunodeficiency virus testing, treatment and care in a tuberculosis clinic in rural Kenya. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:611–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kerschberger B, Hilderbrand K, Boulle A M, et al. The effect of complete integration of HIV and TB Services on time to initiation of antiretroviral therapy: a before-after study. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e46988. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pepper D J, Marais S, Wilkinson R J, Bhaijee F, Azevedo V D, Meintjes G. Barriers to initiation of antiretrovirals during anti-tuberculosis therapy in Africa. PLOS ONE. 2011;6:e19484. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kranzer K, Zeinecker J, Ginsberg P, et al. Linkage to HIV care and antiretroviral therapy in Cape Town, South Africa. PLOS ONE. 2010;5:e13801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Losina E, Bassett I V, Giddy J, et al. The ART of linkage: pre-treatment loss to care after HIV diagnosis at two PEPFAR sites in Durban, South Africa. PLOS ONE. 2010;5:e9538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bassett I V, Wang B, Chetty S, et al. Loss to care and death before antiretroviral therapy in Durban, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:135–139. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181a44ef2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shaffer D N, Obiero E T, Bett J B, et al. Successes and challenges in an integrated tuberculosis/HIV clinic in a rural, resource-limited setting: experiences from Kericho, Kenya. AIDS Res Treat. 2012;2012:238012. doi: 10.1155/2012/238012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawn S D, Campbell L, Kaplan R, Little F, Morrow C, Wood R. Delays in starting antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV-associated tuberculosis accessing non-integrated clinical services in a South African township. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:258. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-11-258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akksilp S, Karnkawinpong O, Wattanaamornkiat W, et al. Antiretroviral therapy during tuberculosis treatment and marked reduction in death rate of HIV-infected patients. Thailand. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1001–1007. doi: 10.3201/eid1307.061506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization . Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in adults and adolescents: 2010 revision. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kenya Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation & Ministry of Medical Services . National recommendations for prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV, infant and young child feeding and antiretroviral therapy for children, adults and adolescents. Nairobi, Kenya: Ministry of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kenya Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation & Ministry of Medical Services . Guidelines for antiretroviral therapy in Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya: Ministry of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Odhiambo J, Gondi J, Miruka F, et al. Models of TB-HIV integration and accomplishments in Nyanza Province, Kenya. Kuala Lumpur: 43rd Union World Conference on Lung Health, 13–17 November 2012; Malaysia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2012; 16 (Suppl 1): S393. [Abstract PC-542-17] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kenya Division of Leprosy Tuberculosis and Lung Disease Nyanza Province TB-HIV program surveillance data. Kisumu, Kenya: Ministry of Health. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kenya Division of Leprosy Tuberculosis and Lung Disease . Annual report. Nairobi, Kenya: Ministry of Health, 2011; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.World Health Organization . Global tuberculosis control, 2012 report. WHO/HTM/TB/2012.6. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2012. [Google Scholar]