Abstract

Setting:

A tertiary medical college hospital in Dhaka City Corporation area, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Objectives:

To identify factors associated with treatment delay among tuberculosis (TB) patients referred from a public diagnostic centre to various DOTS treatment centres in Dhaka City Corporation area, Bangladesh.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 123 patients referred from the Dhaka Medical College Hospital to different DOTS treatment centres during July–October 2012. Factors associated with treatment delay (>1 day between referral and initiation of DOTS treatment) were identified.

Results:

Among the 123 patients referred from the hospital, treatment delay was found to range between 2 and 17 days (median 2). In bivariate analysis, treatment delay was found to be significantly associated with the patient’s diagnostic category. In multivariate analysis, World Health Organization ( WHO) Category II patients were found to be four times more likely to have treatment delay than WHO Category I patients, and married patients were much more likely to have treatment delays than unmarried patients.

Conclusion:

The study findings suggest that the main factors contributing to treatment delay among TB patients were history of previous anti-tuberculosis treatment, marital status and age. Patients should be given extensive information about the dangers of treatment delay before referring them to DOTS treatment centres.

Keywords: delay initiation, DOTS treatment, Dhaka Medical College, Bangladesh

Abstract

Contexte:

Un hôpital tertiaire du Collège Médical de la zone Dhaka City Corporation à Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Objectifs:

Déceler les facteurs associés à un retard du traitement chez les patients TB référés à partir d’un centre de diagnostic public vers divers centres de traitement DOTS dans la zone Dhaka City Corporation, Bangladesh.

Méthodes:

On a mené une étude transversale chez 123 patients référés de l’Hôpital du Collège Médical de Dhaka vers différents centres de traitement DOTS pendant la période de juillet à octobre 2012. On a identifié les facteurs associés à un retard du traitement (durée >1 jour entre la référence et la mise en route du traitement DOTS).

Résultats:

Sur les 1323 patients référés à partir de l’hôpital, on a trouvé un retard du traitement s’étalant de 2 à 17 jours avec une valeur médiane de 2 jours. Dans l’analyse bivariée, on trouve que le retard du traitement est en association significative avec la catégorie de diagnostic du patient. Dans l’analyse multivariée, les patients de Catégorie II de l’OMS s’avèrent quatre fois plus susceptibles de connaître un retard de traitement par comparaison aux patients de Catégorie I. Les patients mariés sont beaucoup plus susceptibles de connaître un retard de traitement par comparaison avec les patients célibataires.

Conclusion:

Les observations de cette étude suggèrent que les facteurs contributifs principaux du retard de traitement chez les patients tuberculeux sont des antécédents d’un traitement antituberculeux antérieur, le statut conjugal et l’âge. Il y aurait lieu de donner aux patients des informations étendues concernant les dangers du retard du traitement avant de les référer vers les centres de traitement DOTS.

Abstract

Marco de referencia:

Un hospital universitario de atención terciaria en la zona de la Corporación de la Ciudad de Daca, en Bangladesh.

Objetivos:

Encontrar los factores que se asocian con el retraso del tratamiento antituberculoso en los pacientes remitidos de un establecimiento público de diagnóstico a diversos centros de administración del tratamiento DOTS en la zona de la Corporación de la Ciudad de Daca, de Bangladesh.

Métodos:

Fue este un estudio transversal realizado con 123 pacientes remitidos del Hospital Universitario de la Facultad de Medicina de Daca a diferentes centros de suministro de DOTS entre julio y octubre del 2012. Se determinaron los factores asociados con el retraso del tratamiento (más de un día entre la remisión y el comienzo del tratamiento en DOTS).

Resultados:

Se observó que en los 123 pacientes remitidos del hospital, el retraso del tratamiento osciló entre 2 y 17 días, con una mediana de 2 días. En un análisis bifactorial se encontró que el retraso del tratamiento se asociaba de manera significativa con la categoría diagnóstica del paciente. El análisis multifactorial puso en evidencia que era cuatro veces más posible que presentaran un retraso del tratamiento los pacientes de la Categoría II del OMS, comparados con los pacientes de la Categoría I. Fue mucho más probable el retraso en los pacientes casados que en los solteros.

Conclusión:

Los resultados del estudio indican que los principales factores que contribuyen al retraso del tratamiento son el antecedente de tratamiento antituberculoso, el estado civil y la edad. Es preciso aportar a los pacientes información exhaustiva sobre los riesgos del retraso del tratamiento antes de remitirlos a los centros de suministro de DOTS.

With a population of about 150 million, tuberculosis (TB) is a major public health problem in Bangladesh.1 Each year, over 330 000 persons in Bangladesh develop TB, of whom 64 000 die.2 In 2012, Bangladesh was ranked sixth on the list of the 22 high TB burden countries in the world, and one of the five high-burden countries in the World Health Organization (WHO) South-East Asia Region.3 The Government of Bangladesh introduced the DOTS strategy in 1993 and adopted it as a national strategy in 1994, extending it to cover the entire country with the collaboration of its partner non-governmental organisations to reduce the burden of TB until it ceases to be a public health problem.4

For an effective TB control programme, early diagnosis of TB patients and prompt initiation of DOTS treatment is essential.5 Although the Bangladesh National Tuberculosis Control Programme (NTP) guidelines clearly mention that anti-tuberculosis treatment should be started as soon as possible after diagnosis,1 previous studies conducted in Bangladesh have reported delays in care seeking, diagnosis and initiation of treatment.6,7

Delays in diagnosis and treatment initiation may aggravate disease conditions and clinical outcomes, and enhance transmission of TB in the community.8,9 This is a major public health problem in densely populated countries such as Bangladesh. It is very important to identify and eliminate the various underlying factors for delay.

The objective of the present study was to identify factors associated with treatment delay among TB patients referred from a public diagnostic centre to various DOTS treatment centres in the Dhaka City Corporation (DCC) area, Bangladesh.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting

In Bangladesh, BRAC is one of the 43 institutions with which the NTP has been working as part of a public-private partnership for TB control. In 2004, BRAC created ‘DOTS Corners’, facilities dedicated to TB testing and treatment services, allowing patients to seek TB services, and serving as a source of diagnosis and referral.10

In 2011, BRAC had 24 DOTS Corners, including one in the Dhaka Medical College (DMC). The DMC DOTS Corner diagnoses all forms of TB, both pulmonary and extra-pulmonary, including sputum-negative cases. After diagnosis, BRAC staff discuss convenient treatment options with the patients. Patients who are not registered with a DOTS Corner are referred to a DOTS treatment centre that is close to their place of residence.10

Although this model is effective and efficient to an extent, it requires strong links between providers to ensure that patients are not lost or suffer delays between diagnosis and treatment.10

Study participants

The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to recruit study subjects. Inclusion criteria: 1) patients registered at any of the DOTS treatment centres for treatment after referral from the DMC Hospital between July and October 2012, and 2) patients who provided informed consent and agreed to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria: 1) patients started on DOTS treatment at the DMC Hospital before being referred to a DOTS treatment centre, 2) patients who failed to initiate DOTS treatment at any of the treatment centres after referral, 3) patients who lived outside the DCC area, and 4) those aged <14 years (childhood TB cases).

All patients who were eligible for the study were visited at home or at the DOTS treatment centres at their convenience and recruited unless they refused to participate. Data were collected from a total of 123 patients.

Data collection

A semi-structured questionnaire was used for data collection. The questionnaire was first developed in English, translated into Bengali, then back-translated into English. Issues regarding potential recall bias were taken into account by including counter-checked questions in the questionnaire. Questions about different aspects of knowledge, perception and stigma were analysed individually, and internal consistency was checked using the Cronbach’s α statistic. Cronbach’s α = 0.804 indicated high internal consistency.

Eighteen field researchers were introduced to the questionnaire and given orientation training on data collection. The questionnaire was also pre-tested and revised. Data were collected through face-to-face interviews.

Variables

The outcome variable ‘treatment delay’ was defined as the difference between the patient’s referral date collected from the register of the DMC DOTS Corner and the date the patient registered for initiation of treatment at the DOTS treatment centre, obtained from the DOTS treatment centre. Treatment delay was calculated from these two dates.

There is no consensus in defining the standard cut-off point for ‘delay’ in care seeking and treatment initiation in the case of TB.11 In previous studies, 7, 14 or 30 days were used as the cut-off point based on the context of the study,11–13 while in some studies the median value of the observed data was used as the cut-off.14–16 This study adopted the latter method to dichotomise treatment delay. A patient with >1 day between referral and initiation of treatment was considered as having experienced ‘treatment delay’.

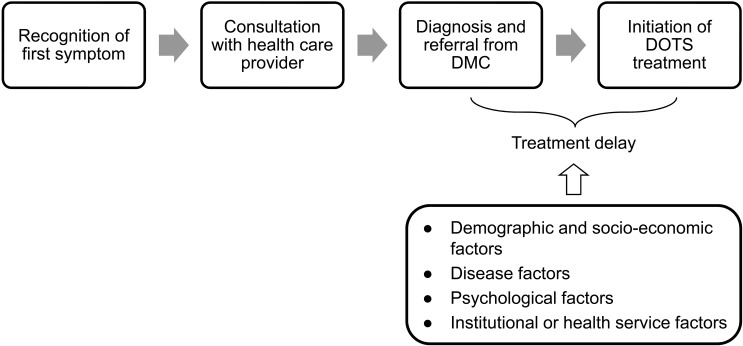

Possible factors associated with treatment delay were identified from previous studies in the literature. Different independent variables considered for the study include demographic and socio-economic characteristics, variables related to current illness, variables regarding TB knowledge, perception and related stigma, and variables regarding institutional or health service factors (Figure).

FIGURE.

Conceptual framework of the study (modified and adapted from Yimer et al.15). DMC = Dhaka Medical College.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS, version 16.0 (Statistical Product and Service Solutions, Chicago, IL, USA) and Stata SE, version 12 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA). The χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used, when appropriate, to analyse the association between treatment delay and different socio-economic, demographic and other factors. Unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) were calculated using univariate logistic regression analysis. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed on variables that had a significance level of P ⩽ 0.25 in univariate analysis. The sex of the patient was also included in the model as a clinically and practically relevant variable, although it was observed to be non-significant in univariate analysis. Adjusted ORs were used to explain the effect of different socio-economic, demographic and other factors on treatment delay.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the James P Grant School of Public Health, BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Permission to extract data from the DMC DOTS Corner register was also obtained from the BRAC Health, Nutrition and Population Programme and the DMC Hospital. Respondents were fully informed of the purpose of the study and their right to refuse to answer any question and to terminate the interview at any point. Informed consent was provided by respondents before each interview.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

From July to October 2012, the DMC DOTS Corner referred 203 patients to different DOTS treatment centres in Dhaka City. Among these, 123 patients (60.6%) attended the treatment centres and initiated DOTS treatment; 39.4% of the referred patients were lost to treatment.

The mean age of the 123 patients who initiated DOTS treatment was 30.6 years (standard deviation [SD] 14.6, median 26); 39.1% were male, most of whom (54.4%) were currently working. The remaining 45.6% of the respondents were housewives, students or retired persons. More than half of the patients (62.6%) were married. The median monthly income of the respondents was 12 000 Bangladeshi Taka (BDT; 1 BDT = US$0.01); about half of the patients (47.2%) had a monthly income between 10 000 and 20 000 BDT (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Socio-economic characteristics of 123 patients who initiated DOTS treatment in DOTS treatment centres

| Sources of variability | n (%) |

| Referred patients who attended treatment centre and were started on treatment (N = 203) | 123 (60.6) |

| Age, years (n = 123) | |

| Mean ± SD | 30.6 ± 14.6 |

| Median [IQR] | 26 [20–37] |

| <20 | 24 (19.5) |

| 20–39 | 69 (56.1) |

| 40–59 | 24 (19.5) |

| ≥60 | 6 (4.9) |

| Sex (n = 123) | |

| Male | 48 (39.1) |

| Female | 75 (60.9) |

| Highest level of education (n = 123) | |

| No schooling | 26 (21.1) |

| Primary | 37 (30.1) |

| Secondary | 24 (19.5) |

| Higher secondary | 18 (14.6) |

| Graduated | 16 (13.0) |

| Other | 2 (1.6) |

| Marital status (n = 123) | |

| Single | 44 (35.8) |

| Married | 77 (62.6) |

| Widow/widower | 2 (1.6) |

| Occupation (n = 123) | |

| Currently working | 67 (54.4) |

| Housewife | 18 (14.6) |

| Student | 19 (15.5) |

| Unemployed and retired | 19 (15.5) |

| Number of household members (n = 123), mean ± SD | 5.0 ± 2.3 |

| <5 | 60 (48.8) |

| ≥5 | 63 (51.2) |

| Monthly household income (in BDT) (n = 123), median [IQR]* | 12 000 [9000–20 000] |

| <10 000 | 33 (26.8) |

| 10 000–19 999 | 58 (47.2) |

| 20 000–29 999 | 15 (12.2) |

| ≥30 000 | 17 (13.8) |

| Smoking history (n = 119) | |

| Current smoker | 9 (7.6) |

| Ex-smoker | 19 (15.9) |

| Never smoked | 91 (76.5) |

1 BDT = US$0.01.

SD = standard deviation; IQR = interquartile range; BDT = Bangladeshi Taka.

Treatment delay

We calculated treatment delay based on the dates of referral and treatment initiation. Treatment delay, experienced by 41/123 patients (33.3%; Table 2), ranged from 2 to 17 days (median 2, mean 4.1, SD 3.7).

TABLE 2.

Proportion of patients with different ranges of treatment delay

| Treatment delay, days | Frequency (n = 41) n (%) |

| 2 | 21 (51.2) |

| 3 | 7 (17.1) |

| 4 | 3 (7.3) |

| 5 | 2 (4.9) |

| 6 | 1 (2.4) |

| 7 | 1 (2.4) |

| 8 | 1 (2.4) |

| 10 | 1 (2.4) |

| 12 | 2 (4.9) |

| 13 | 1 (2.4) |

| 17 | 1 (2.4) |

In univariate logistic regression analysis, treatment delay was significantly associated with the diagnostic category of the patient (unadjusted OR 3.56, 95%CI 1.17–10.83, P = 0.025). No significant association was found between other variables and treatment delay (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Association between treatment delay and different socio-economic, demographic and other factors

| Variable | Patients with treatment delay (n = 41) n (%) | Patients without treatment delay (n = 82) n (%) | χ2 | P value |

| Age | ||||

| Older age group (>26 years) | 17 (41.5) | 43 (52.4) | 1.318 | 0.250 |

| Younger age group (≤26 years) | 24 (58.5) | 39 (47.6) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 17 (41.5) | 31 (37.8) | 0.154 | 0.695 |

| Female | 24 (58.5) | 51 (62.2) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 10 (24.4) | 34 (41.5) | 3.468 | 0.063 |

| Married | 31 (75.6) | 48 (58.5) | ||

| Monthly income, BDT* | ||||

| <10 000 | 8 (19.5) | 25 (30.5) | 2.550 | 0.466 |

| 10 000–19 999 | 22 (53.6) | 36 (43.9) | ||

| 20 000–29 999 | 4 (9.8) | 11 (13.4) | ||

| ≥30 000 | 7 (17.1) | 10 (12.2) | ||

| Diagnostic category | ||||

| WHO Category I | 32 (78.0) | 76 (92.7) | 5.467 | 0.019 |

| WHO Category II | 9 (22.0) | 6 (7.3) | ||

| Sought health care with informal provider before going to formal provider | ||||

| No | 36 (87.8) | 75 (91.5) | 0.416 | 0.532† |

| Yes | 5 (12.2) | 7 (8.5) | ||

| Tuberculosis-related stigma | ||||

| No | 22 (53.7) | 46 (56.1) | 0.066 | 0.798 |

| Yes | 19 (46.3) | 36 (43.9) |

1 BDT = US$0.01.

Fisher’s exact test.

BDT = Bangladeshi Taka; WHO = World Health Organization.

In multiple logistic regression analysis, treatment delay was found to be significantly associated with patient’s diagnostic category, age and marital status (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

ORs of factors associated with treatment delay in 123 patients referred from Dhaka Medical College DOTS Corner

| Variable | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Age | ||||

| Older age group (>26 years) | 1.00 (reference) | 0.254 | 1.00 (reference) | 0.006 |

| Younger age group (≤26 years) | 0.98 (0.95–1.01) | 4.09 (1.48–11.23) | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 1.00 (reference) | 0.695 | 1.00 (reference) | 0.109 |

| Female | 0.85 (0.39–1.84) | 0.47 (0.19–1.18) | ||

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 1.00 (reference) | 0.066 | 1.00 (reference) | 0.003 |

| Married | 2.19 (0.95–5.07) | 5.61 (1.83–17.18) | ||

| Diagnostic category | ||||

| WHO Category I | 1.00 (reference) | 0.025 | 1.00 (reference) | 0.020 |

| WHO Category II | 3.56 (1.17–10.83) | 4.26 (1.25–14.51) | ||

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; WHO = World Health Organization.

Diagnostic category

Multiple logistic regression results revealed that diagnostic category was significantly associated with treatment delay. WHO Category II patients (retreatment cases with a previous history of anti-tuberculosis treatment of >1 month’s duration) were 4.26 times more likely to experience treatment delay than Category I (new) patients, after adjusting for age group, sex and marital status (adjusted OR [aOR] 4.26, 95%CI 1.25–14.51, P = 0.020).

Marital status

Univariate logistic regression analysis showed no significant association between treatment delay and patients’ marital status (unadjusted OR 2.19, 95%CI 0.95–5.07, P = 0.066). However, in multivariate analysis, marital status was found to be significantly associated with treatment delay after adjusting for sex, age group and diagnostic category. Multiple logistic regression results suggest that married patients were 5.61 times more likely to experience treatment delay than single patients (aOR 5.61, 95%CI 1.83–17.18, P = 0.003).

Age

Age was found to be statistically significantly associated with treatment delay in multiple logistic regression analysis after adjusting for patients’ sex, marital status and diagnostic category. Younger patients (⩽26 years) were 4.09 times more likely to have treatment delay than older patients (>26 years; aOR 4.09, 95%CI 1.48–11.23, P = 0.006).

DISCUSSION

Although the Bangladesh National TB Control guidelines recommend that anti-tuberculosis treatment be started as soon as possible after diagnosis,1 this study found that there were delays in initiating DOTS treatment among patients referred from DMC DOTS Corners. The longest interval between referral and initiation of treatment was 17 days. A study conducted in Bangladesh also found treatment delays in both male and female patients ranging from 0 to 43 days in males and from 0 to 35 days in females (mean 1.9 vs. 2.0, median 1 vs. 1).6

Previous anti-tuberculosis treatment history

The study found that WHO Category II patients were more likely to have delayed seeking treatment than Category I patients (aOR 4.26, 95%CI 1.25–14.51). This finding is consistent with findings from a previous study conducted in India which also found that retreatment cases were more likely to experience treatment delays than new cases (OR 1.8, 95%CI 1.4–2.2).17 One of the main reasons could be the fact that retreated patients were reluctant to be put on the Category II regimen, which consists of 2 months of daily intramuscular streptomycin injections.

Marital status

The study findings showed that marital status was significantly associated with treatment delay. When controlled for age, sex and diagnostic category, married patients were more likely to have treatment delays than single patients (aOR 5.61, 95%CI 1.83–17.18). A study conducted in India also reported that single patients were less likely to have treatment delays than married patients (OR 0.8, 95%CI 0.3–1.8), although the result was not statistically significant.11 One of the underlying reasons why married patients were more likely to experience treatment delays than single patients could be family or social obligations which limited the time they could spend on health care.18

Age

The study also revealed that patient age was significantly associated with treatment delays. However, this finding is not consistent with most of the findings from a systematic review.19 A study conducted in Ethiopia reported that older persons were more likely to have treatment delays than younger persons (OR 2.3, 95%CI 1.2–4.5).20 In our study, we found that persons from the younger age group (⩽26 years) were more likely to experience treatment delays than those from the older age group (>26 years). In the light of the social context of our study, one of the reasons could be the fact that patients aged <26 years were mostly students and would be expected to undergo treatment during school hours, leading to treatment delay.

Other findings

A previous study conducted in Bangladesh found that sex was strongly associated with treatment delay.6 Karim et al. mentioned that female TB patients experienced significantly longer delays than males in health care seeking, diagnosis and initiation of DOTS-based treatment.6 Many other studies conducted in different settings also found that delays at every stage of health care seeking and the clinical process of TB control were significantly longer in females than in males.12,21–23 However, we did not find any significant associations between sex and treatment delay in our study. The findings from our study are consistent with those of another study conducted in Bangladesh,7 in which the researchers found no significant association between sex and treatment delay.

Another contradictory finding was the association of informal health care with treatment delay. In 2011, Rifat et al. found that seeking treatment from informal providers before formal providers was significantly associated with treatment delay (health system delay). In that study, 52% of patients with treatment delays consulted informal providers first (Pearson χ2, P < 0.05).7 However, in our study, no significant association was found between informal health care providers and treatment delays. In the study by Rifat et al., respondents were recruited from both urban and rural areas. We recruited the patients from the DCC area only, which is a limitation of the study. This contradictory finding might be due to the difference in selecting study participants, as in Bangladesh informal health care providers are more common in rural areas.24,25

Study limitations

As previously mentioned, we recruited respondents only from the DCC area. Reasons for treatment delay may be different among those who live in other cities or in rural areas. Our study results therefore cannot be generalised to all TB patients in Bangladesh.

Due to the limited timeframe and resources, we were not able to trace referred patients who were lost between referral and treatment. Furthermore, as we recruited only those patients who attended DOTS treatment centres, we were not able to identify all the factors associated with the failure to initiate treatment. It would be a great benefit to the community if we could also conduct a study on those patients lost after referral.

CONCLUSION

Although our study has limitations, it clearly highlights delays in treatment initiation among patients referred from a public referral point to different treatment centres. This is of public health concern and is worthy of serious attention by programme implementers. We hope that the factors and reasons for treatment delay will be explored further, and that delays in treatment initiation will be reduced as much as possible. This will help to reduce the TB burden in Bangladesh in terms of disease infectivity and morbidity, with as the final goal a country free from the threat of TB.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the BRAC Urban Health Programme staff who helped in pre-testing the questionnaires and collecting data. They also extend their sincere thanks to Professor M Saker from the James P Grant School of Public Health for her precious guidance and advice in designing the study and N Ishikawa for his help with the creation and evaluation of the Dhaka TB programme.

This study was partly supported by the James P Grant School of Public Health (BRAC University) and the BRAC Health, Nutrition and Population Program, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

This study was submitted to the James P Grant School of Public Health (BRAC University) as a Masters level individual thesis in partial fulfilment of MPH degree. The poster version of this study was presented at the graduation forum of the eighth batch MPH, James P Grant School of Public Health at Dhaka, Bangladesh, in January 2013 and awarded the gold medal as the best thesis poster.

Publication was supported by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Bangladesh National Tuberculosis Control Programme . National guidelines and operational manual for tuberculosis control. 4th ed. Dhaka, Bangladesh: NTP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . Global tuberculosis control 2011. WHO/HTM/TB/2011.16. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2011. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2011/9789241564380_eng.pdf Accessed November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization . Tuberculosis in the South-East Asia Region. New Delhi, India: WHO; 2012. http://www.searo.who.int/linkfiles/tuberculosis_who-tb-report-2012.pdf Accessed November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bangladesh National Tuberculosis Control Programme . Guidelines on public private mix for tuberculosis control. Dhaka, Bangladesh: NTCP; 2006. http://ntpban.org/download/ppmguideline.pdf Accessed November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hussen A, Biadgilign S, Tessema F, Mohammed S, Deribe K, Deribew A. Treatment delay among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in pastoralist communities in Bale Zone, Southeast Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:320. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karim F, Islam M A, Chowdhury A, Johansson E, Diwan V K. Gender differences in delays in diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis. Health Policy Plan. 2007;22:329–334. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czm026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rifat M, Rusen I D, Islam Md A, et al. Why are tuberculosis patients not treated earlier? A study of informal health practitioners in Bangladesh. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15:647–651. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asch S, Leake B, Anderson R, Gelberg L. Why do symptomatic patients delay obtaining care for tuberculosis? Ame J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1244–1248. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.4.9709071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karki D K, Joshi A B, Pathak R P. Delay in tuberculosis treatment in Kathmandu Valley. Nepal. Kathmandu, Nepal: Tribhuvan University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Islam M A, May M A, Ahmed F, Cash R A, Ahmed J. Making tuberculosis history: community-based solutions for millions. Dhaka, Bangladesh: University Press Limited; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamhane A, Ambe G, Vermund S, Kohler C L, Karande A, Sathiakumar N. Pulmonary tuberculosis in Mumbai, India: factors responsible for patient and treatment delays. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3:569–580. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pirkis J E, Speed B R, Yung A P, Dunt D R, Maclntyre C R, Plant A J. Time to initiation of anti-tuberculosis treatment. Tubercle Lung Dis. 1996;77:401–406. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(96)90111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wandwalo E R, Mørkve O. Delay in tuberculosis case-finding and treatment in Mwanza, Tanzania. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2000;4:133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gele A, Bjune G, Abebe F. Pastoralism and delay in diagnosis of TB in Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yimer S, Bjune G, Alene G. Diagnostic and treatment delay among pulmonary tuberculosis patients in Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis. 2005;5:112. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-5-112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bassili A, Seita A, Baghdadi S, et al. Diagnostic and treatment delay in tuberculosis in 7 countries of the Eastern Mediterranean Region. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2008;16:23–35. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paul D, Busireddy A, Nagaraja S B, et al. Factors associated with delays in treatment initiation after tuberculosis diagnosis in two districts of India. PLOS ONE. 2012;7:e39040. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Somma D, Auer C, Abouihia A, Weiss M G. Gender in tuberculosis research. Vol. 2004. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Gender, Women and Health, World Health Organization; http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2004/9241592516.pdf Accessed November 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Storla D G, Yimer S, Bjune G. A systematic review of delay in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mesfin M M, Tasew T W, Tareke I G, Kifle Y T, Karen W H, Richard M J. Delays and care seeking behavior among tuberculosis patients in Tigray of northern Ethiopia. Ethiopian J Health Dev. 2005;19:7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hudelson P. Gender differentials in tuberculosis: the role of socio-economic and cultural factors. Tubercle Lung Dis. 1996;77:391–400. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(96)90110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long N H, Johansson E, Lönnroth K, Eriksson B, Winkvist A, Diwan V K. Longer delays in tuberculosis diagnosis among women in Vietnam. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 1999;3:388–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Needham D M, Foster S D, Tomlinson G, Godfrey-Faussett P. Socio-economic, gender and health services factors affecting diagnostic delay for tuberculosis patients in urban Zambia. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:256–259. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmed S M, Adams A M, Chowdhury M, Bhuiya A. Changing health-seeking behaviour in Matlab, Bangladesh: do development interventions matter? Health Policy Plann. 2003;18:306–315. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czg037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hosain G M, Ganguly K C, Chatterjee N, Atkinson D. Use of unqualified practitioners by disabled people in rural Bangladesh. Mymensingh Med J. 2005;14:160–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]