Abstract

PURPOSE

We aimed to investigate the efficacy and safety of preoperative selective intra-arterial embolization (PSIAE) in the surgical treatment of large liver hemangiomas.

METHODS

Data of 22 patients who underwent resection of large liver hemangiomas were retrospectively analyzed. PSIAE was performed in cases having a high risk of severe blood loss during surgery (n=11), while it was not applied in cases with a low risk of blood loss (n=11).

RESULTS

A total of 19 enucleations and six anatomic resections were performed. Operative time, intraoperative bleeding amount, Pringle period, and blood transfusion were comparable between the two groups (P > 0.05, for all). The perioperative serum aspartate transaminase level was not different between groups (P = 1.000). Perioperative total bilirubin levels were significantly increased in the PSIAE group (P = 0.041). Postoperative hospital stay was longer in the PSIAE group. Surgical complications were comparable between groups (P = 0.476).

CONCLUSION

Patients who underwent PSIAE due to a high risk of severe blood loss during resection of large liver hemangiomas had comparable operative success as patients with a low risk of blood loss who were operated without PSIAE. Hence, PSIAE can be used for the control of intraoperative blood loss, especially in surgically difficult cases.

Hepatic hemangiomas are the most common benign tumors of the liver. The incidence in autopsy series ranges from 0.4% to 7.3% (1). According to epidemiologic studies, estimated prevalence is 5% to 20% in the general population (2, 3). Most hepatic hemangiomas are less than 1 cm in diameter, and are usually followed without treatment in the absence of symptoms or complications. However, when they are large (>4 cm), patients may suffer from abdominal discomfort or pain caused by capsular stretch and experience early satiety from gastric compression. Additionally, spontaneous or traumatic rupture of a hemangioma is a mortal complication. In patients with large hemangiomas, consumptive coagulopathy with low platelet count and hypofibrinogenemia (Kasabach-Merritt syndrome) is also an important clinical problem.

Management of patients with large hemangiomas of the liver has been controversial. Operative bleeding during enucleation or resection of a large liver hemangioma is an important cause of morbidity and mortality (4). However, preoperative embolization of large hemangiomas can reduce operative bleeding related with the hepatic arterial supply. Selective embolization through the left or right hepatic arteries is thought to reduce morbidity compared with nonselective embolization of the proper hepatic artery or ligation of the common hepatic artery (5).

In the present study, the effect of preoperative selective intra-arterial embolization (PSIAE) of large hemangiomas on operative bleeding was evaluated retrospectively. Preoperative variables, complications, and the hospital course of patients were compared with the control group.

Methods

Between January 2007 and December 2013, a total of 165 patients underwent liver resection in our Department of Surgery. According to our clinical policy, large hemangioma is not a common indication for liver resection (6, 7). In that period, 74 patients with hemangioma were referred to our center. Forty-four of these patients had large liver hemangiomas.

Twenty-two patients with large liver hemangiomas were followed without surgical treatment, because their symptoms were found unrelated with hemangioma and were diagnosed with chronic gastritis (n=12), cholelithiasis (n=8), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (n=2). Fifteen of the 22 patients were followed by abdominal computed tomography (CT) annually. The remaining seven patients were lost to follow-up. We followed large hemangiomas by CT annually in the first year after diagnosis. If the size of hemangioma was stable, further control points were three years after diagnosis and every five years thereafter. Median follow-up was 44.5 months (13–79 months). During the follow-up period only one patient presented with spontaneous rupture of hemangioma.

The remaining 22 patients with symptoms related to the presence of large liver hemangiomas underwent surgery (with PSIAE [n=11] or without PSIAE [n=11]) establishing the two study groups of this paper. All patients were symptomatic, with one or more symptoms related to their disease. The most common symptoms were abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and early satiety. On physical examination, seven patients had hepatomegaly and five patients had tenderness on the right upper quadrant of the abdomen. Liver enzymes were found in normal range preoperatively. Anemia was noticed in only one patient. All patients had an abdominal CT examination, except three patients in whom hemangiomas were detected by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

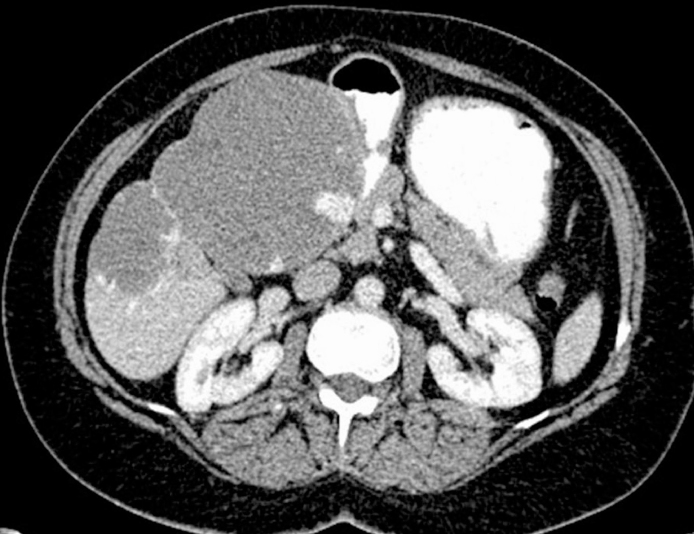

Data of patients who underwent surgical treatment were prospectively recorded and retrospectively analyzed. Medical records, diagnostic methods, laboratory examinations, and patient follow-up were evaluated. Hemangiomas were diagnosed at our institution through abdominal CT, MRI, or ultrasonography (Fig. 1). Percutaneous biopsy of the tumor was not performed before operation. The size and location of hemangiomas were estimated on the basis of surgical specimens and radiologic studies. Liver hemangiomas ≥ 5 cm in diameter are defined as large (4). Perioperative morbidity and mortality included complications or death during the hospital stay or within 30 days of operation. Perioperative morbidity was categorized according to Dindo’s classification (8).

Figure 1.

CT image shows a cavernous hemangioma in segments IVB, V, and VI. The largest diameter of the lesion was 13 cm.

Follow-up protocol for the patients who underwent surgical treatment was the same as the follow-up of patients without surgical treatment. They were followed with CT imaging in the first year after operation, and further controls were performed three years after diagnosis and every five years thereafter.

Selection criteria for preoperative embolization

Patients underwent surgical treatment with preoperative embolization (PSIAE group, n=11) or without preoperative embolization (non-PSIAE group, n=11). The selection of patients for PSIAE depended on the location of hemangioma and expected operative difficulty. Centrally located liver hemangiomas, hemangiomas located close to the hepato-caval junction, hemangiomas located in caudate lobe and hemangiomas closely related with hepatic veins or portal structures are associated with significant bleeding risk and operative difficulty. The procedure related risks were shared with patients, informed consent was obtained and only approved patients were included in the PSIAE group. Additional surgery was required in one patient in the PSIAE group: cholecystectomy was added to the procedure due to localization of the hemangioma (segments IVB-V-VI). Additional surgery in this patient was inevitable, therefore, it is not considered as a reason for exclusion from the study.

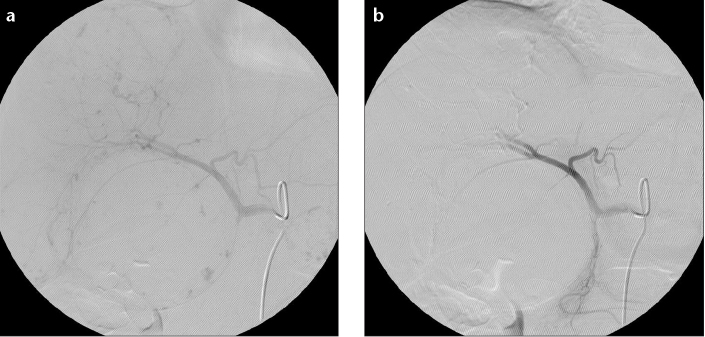

Embolization procedure

After routine preoperative laboratory studies, endovascular procedures were performed with application of premedication including H1 and H2 blockers, antiemetics and narcotics. Under sedation and local anesthesia, a 5 F introducer sheath was inserted into a common femoral artery (mostly right) using the Seldinger technique. Prior to embolization, a diagnostic study including a nonselective aortography through a 4–5 F pig-tail catheter, selective angiographies of the celiac trunk and superior mesenteric artery with 4–5 F diagnostic catheters were obtained to investigate possible variations such as replaced right or left hepatic arteries and to see additional feeders of the lesions such as inferior phrenic artery (Fig. 2a). After familiarization with the patient’s vascular anatomy, the feeders of the hemangiomas were selectively catheterized with either the 4 F hydrophilic diagnostic catheters (Glidecath, Terumo Corp.) or a coaxially placed 2.4 F microcatheter (Progreat, Terumo Corp.) depending on calibration and/or tortuosity of the vessels. For embolization of the hemangioma, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles of 355–500 µm (Contour, Boston Scientific) suspended in 10–20 mL of iodinated contrast (diluted 1:1) were administered through the positioned catheters until stasis of flow was established (Fig. 2b). Control angiograms revealed complete embolization in all cases. The procedures ended with routine femoral compression for hemostasis. In the PSIAE group, surgery was planned three days after the embolization.

Figure 2. a, b.

Selective angiography of the celiac trunk before intra-arterial embolization (a) demonstrates the feeders of the hemangioma. Panel (b) shows successful occlusion of the feeders.

Operative technique and postoperative care

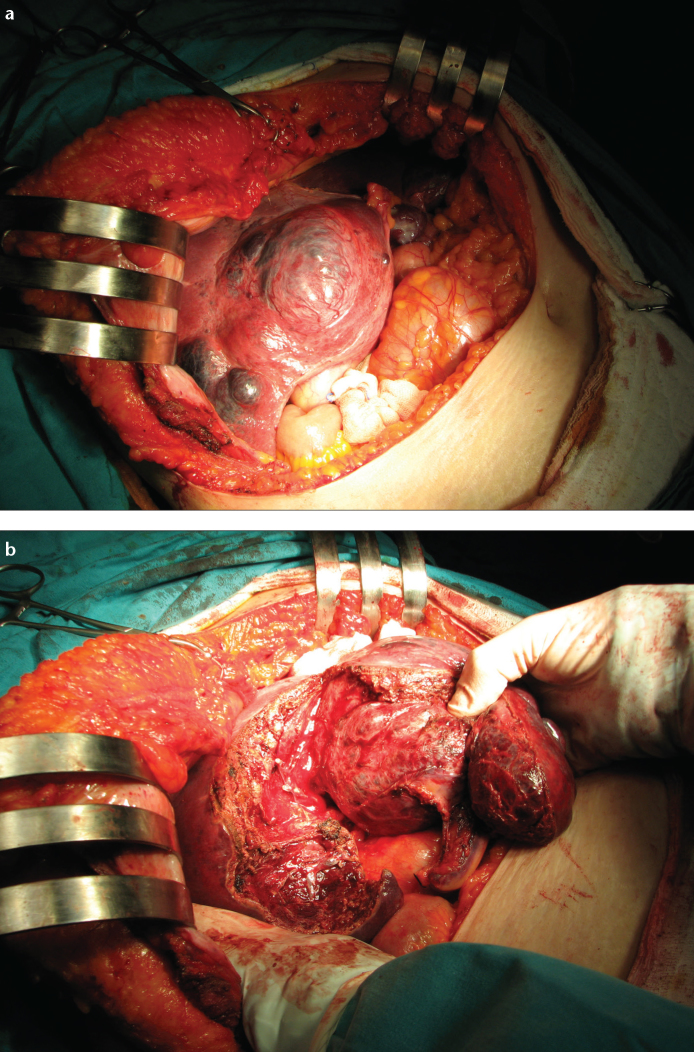

Central vein catheterization was performed routinely, and central venous pressure was maintained below 5 mm Hg during the liver resection. Conventional liver resection or enucleation was performed through a J incision. Demarcation line or necrotic parts of hemangiomas were determined in the PSIAE group (Fig. 3a). Extraparenchymal control of ipsilateral inflow and outflow was attempted before resection. Resection was performed under intermittent portal triad clamping (10 min clamping, 5 min reperfusion) in general. Liver transection was performed with the combination of clamp crushing method and harmonic scalpel (SonoSurg, Olympus KeyMed). We used Bismuth’s terminology for hepatectomy (segmental and sectorial division of liver parenchyma) in this study (9). Major hepatectomy was defined as the resection of three or more segments. Enucleation was defined according to the technique described by Alper, Blumgart, and Nagorney (Fig. 3b) (10–12). Caudate lobectomy was performed according to the technique previously described by Nagorney (13). All patients received antibiotic prophylaxis. Extubation of the patient in the operating room was achieved in all patients. Patients with uneventful operative course were transferred to the surgical ward after extubation (n=22). Prophylactic daily subcutaneous injection of low-molecular-weight heparin sodium was started on postoperative day 0.

Figure 3. a, b.

Preoperative selective intra-arterial embolization of hemangioma was associated with slight necrosis at day 3 postembolization (a). Panel (b) shows the dissection plan during enucleation.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 11.0; SPSS Inc.). Comparative analysis of categorical variables was performed using Fisher’s exact test. Comparative analysis of quantitative variables was performed using Mann Whitney U test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Demographics of the patients were presented in Table 1. Median age was 46.8 years in the PSIAE group and 45.3 years in the non-PSIAE group (P = 0.688). Female predominance was observed in both groups. Characteristics of the hemangiomas were summarized in Table 2. The majority of hemangiomas was located in the right lobe (n=17). The left lobe (n=6) and the caudate lobe of the liver (n=2) were also influenced. Multiple large hemangiomas were either bilobar (n=2) or detected in the right lobe and the caudate lobe (n=1). PSIAE was performed in 11 patients, while surgical treatment without PSIAE was performed in the remaining 11 patients. No PSIAE-related complication occurred during the study period.

Table 1.

Preoperative variables and hospital course of the study groups

| Parameters | PSIAE n=11 | Non-PSIAE n=11 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 46.8 (36–56) | 45.3 (32–54) | 0.688 |

| Gender (F/M) | 10 (90.9)/1 (9.1) | 9 (81.8)/2 (18.2) | 1.000 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.9 (20.7–30.5) | 27.6 (20–34) | 0.734 |

| ASA | 1.000 | ||

| ASA score <2 | 6 (54.5) | 7 (63.6) | |

| ASA score ≥2 | 5 (45.5) | 4 (36.4) | |

| Preoperative co-morbidities | 1.000 | ||

| Anemia | 1 (9.1) | 0 | |

| Surgical treatment | |||

| Enucleation | 10 (90.9) | 9 (81.8) | 1.000 |

| Left lobectomy | 0 | 1 (9.1) | 1.000 |

| Posterior sectorectomy | 0 | 1 (9.1) | 1.000 |

| Lateral sectorectomy | 1 (9.1) | 1 (9.1) | 1.000 |

| Caudate lobectomy | 2 (18.2) | 0 | 0.476 |

| Additional surgical procedure | 1.000 | ||

| Cholecystectomy | 1 (9.1) | 0 | |

| Operation time (min) | 177.3 (50–330) | 123 (50–210) | 0.145 |

| Operative bleeding amount (mL) | 232 (50–500) | 216.6 (50–600) | 0.530 |

| Pringle period (min) | 31 (10–70) | 23.3 (10–40) | 0.377 |

| Blood transfusion requirement | 3 (27.3) | 2 (18.2) | 1.000 |

| FFP transfusion requirement | 8 (72.7) | 9 (81.8) | 1.000 |

| Serum AST (U/L) | |||

| Day 2 after PSIAE | 24.1 (13–54) | - | - |

| Postoperative day 2 | 150.1 (60–343) | 141.4 (26–294) | 1.000 |

| Serum total bilirubin (mg/dL) | |||

| Day 2 after PSIAE | 0.66 (0.2–1.5) | - | - |

| Postoperative day 2 | 1.13 (0.4–2.2) | 0.57 (0.2–0.9) | 0.041 |

| Postoperative morbidity | 2 (18.2) | 0 | 0.476 |

| Bile leakage | 1 (9.1) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Pneumonia | 1 (9.1) | 0 | 1.000 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (days) | 11.3 (8–18) | 6.3 (4–7) | 0.031 |

| 30-day mortality | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - |

Data are given as either median (min–max) or n (%).

F, female; M, male; BMI, body mass index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; FFP, fresh frozen plasma; AST, aspartate transaminase; PSIAE, preoperative selective intra-arterial embolization.

Table 2.

Hemangioma characteristics

| Parameters | PSIAE | non-PSIAE | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location, n (%) | |||

| Right lobe | 9 (81.8) | 8 (72.7) | 1.000 |

| Segment VIII | 3 | 4 | |

| Segment VII | 2 | 1 | |

| Segment VI | 1 | 1 | |

| Segments VI–VII–VIII | 1 | 0 | |

| Segments VII–VIII | 0 | 1 | |

| Segments VI–VII | 0 | 1 | |

| Segments V–VI | 1 | 0 | |

| Segments IVB–V–VI | 1 | 0 | |

| Left lobe | 2 (18.2) | 4 (36.4) | 0.635 |

| Segment III | 0 | 1 | |

| Segment II | 1 | 1 | |

| Segments II–III–IVB | 0 | 1 | |

| Segments II–III | 1 | 1 | |

| Caudate lobe | 2 (18.2) | 0 | 0.476 |

| Diameter of hemangioma (cm), median (min–max) | 7.4 (5–14) | 8.8 (5–16) | 0.149 |

| Single hemangioma, n (%) | 9 (81.8) | 10 (90.9) | 1.000 |

| >1 hemangioma, n (%) | 2 (18.2) | 1 (9.1) | 1.000 |

PSIAE, preoperative selective intra-arterial embolization

Enucleation was preferred in the majority of patients (16/22). Liver resection was performed in six patients due to the location of the hemangioma and relation of the hemangioma with the vascular structures of the liver.

As demonstrated in Table 1, operative time and Pringle period were similar in both groups (P = 0.145 and P = 0.377, respectively). Estimated blood loss and transfusion requirements were comparable between the two groups. Hemorrhage during liver resection was replaced by fresh frozen plasma in 17 patients. Transfusion with erythrocyte suspension was required in five of 22 patients. There was no significant difference in perioperative serum aspartate transaminase levels between the groups (P = 1.000).

The perioperative total bilirubin level was significantly increased in the PSIAE group compared to the non-PSIAE group (P = 0.041). The elevation of bilirubin levels in the PSIAE group was transient and returned to normal range before discharge.

There was no significant difference in the morbidity between the groups (P = 0.476). Postoperative complications occurred in two patients. One patient in the PSIAE group suffered from bile leak from the raw surface of the liver after enucleation of the hemangioma from segment VII. This leak ended spontaneously at the end of the first postoperative week (Dindo grade II). Postoperative atelectasis and pneumonia developed in another patient in the PSIAE group. Following intensive pulmonary care and antibiotic treatment, patient was discharged at the end of the second postoperative week (Dindo grade II). Length of postoperative hospital stay was significantly longer in the PSIAE group (P = 0.031). No mortality occurred in either group. Pathological examination of the specimens revealed cavernous hemangioma in all cases (n=22).

Follow-up of the patients included history, physical examination, liver function tests, and CT when necessary. The period of follow-up ranged from three months to five years, with a median follow-up of 30.4 months. One patient in the non-PSIAE group had incisional hernia six months after the operation (n=1). No recurrent hemangioma was observed during the follow-up. No significant liver function test abnormalities were observed in any of the patients.

Discussion

In this study, we show that patients who underwent PSIAE due to a high risk of severe blood loss during resection of large liver hemangiomas had comparable operative success as patients with a low risk of blood loss who were operated without PSIAE. The main drawback of this strategy was the prolonged hospital stay.

One of the most controversial areas of hepatic surgery has been the resection of hemangiomas (14). Several trauma surgeons have advocated the resection of large hemangiomas even in patients who are asymptomatic, because management of hemangiomas after an iatrogenic injury or blunt trauma in centers without a hepatobiliary unit generally ends with a fatal outcome (4). On the other hand, Belghiti et al. (15) stated that the main complication of hemangioma is the surgical operation. However, the presence of severe symptoms, complications, and inability to exclude malignancy are considered as treatment indications for hemangiomas (16).

Surgical resection is the definitive treatment of large hemangiomas, while other less effective options include arterial ligation or embolization, radiation therapy, and percutaneous ablation techniques (4, 15, 17–19). Radiation therapy can reduce the size of the lesion; however, its long-term effects on the liver and adjacent structures may be deleterious (15, 17). Experience on the treatment of hemangiomas with percutaneous ablation techniques has been limited in the literature. Inability to ablate giant hemangiomas (diameter larger than 10 cm) is considered to be an important disadvantage of the procedure (18).

Since embolization therapy tends to be used more widely, it is essential to clarify the source of blood supply to cavernous hemangioma. Both histologic and radiologic studies have shown that the blood supply of cavernous hemangioma is based from the hepatic artery (20, 21). Ultrastructurally, cavernous hemangioma of the liver is similar to that of the artery, not vein. Based on these findings, embolization via the hepatic artery is considered feasible in patients with unresectable cavernous hemangioma of the liver. Arterial ligation may be considered during surgical procedures, allowing manual decompression of large hemangiomas and facilitating their manipulation and enucleation (15, 16). Arterial embolization may be considered for the temporary control of hemorrhage from hemangiomas (15, 22, 23). Additionally, it usually provides symptomatic improvement in large liver hemangiomas if it is considered as a main treatment modality (24). However, size of the lesions usually does not change after arterial embolization (25). Hence, embolization of hepatic hemangiomas is currently not considered a definitive treatment. However, there were reports that arterial embolization for large hemangiomas which were performed prior to surgical resection facilitated mobilization of the liver by shrinking the hemangioma and, consequently, decreased intraoperative hemorrhage (24–29). Considering the various complications and vascular recanalization after embolization which might delay the operation and result in the loss of an opportunity for radical resection, some authors recommend urgent operation after embolization (26). Our waiting interval strategy between PSIAE and surgical resection (three days) was determined according to previous studies on neuroscience (30–32). Kuroiwa et al. (32) demonstrated almost no necrotic lesions one day after embolization. Necrotic lesions were observed two days after embolization. Extended necrotic lesions were noted among patients who underwent surgery at day 4 and thereafter. Additionally, Djindjian et al. (30) recommended an interval of three days, and Brismar and Conqvist (31) suggested that surgery should occur one or two days after embolization. Waiting interval between PSIAE and liver resection in our study is based on decreased vascularity of the hemangioma instead of decreased size or extensive necrosis. As recanalization of the arterial thrombus starts a week after embolization (26), the maximum thrombotic effect of embolization is expected within three to five days.

Surgical treatment of hepatic hemangiomas is performed with low morbidity and minimal mortality in the current era (10, 16, 33–37). Enucleation, hepatic resection, or laparoscopic techniques can be used for surgical treatment. Enucleation is associated with a significantly lower incidence of blood loss and blood transfusion requirement than resection. We prefer enucleation whenever possible and used this technique in 69.5% of patients who underwent surgical treatment. However, massive blood loss remains a problem for large hemangiomas of more than 10 cm in diameter, centrally located liver hemangiomas, hemangiomas located close to the hepato-caval junction and hemangiomas located in caudate lobe (13, 38). Bleeding control at these locations is difficult in general (39). Reported median blood loss during enucleation of hemangiomas ranged from 150 mL to 550 mL (16, 35, 38).

The hypothesis of the current study is that blocking the arterial supply of a hemangioma preoperatively may decrease the amount of intraoperative hemorrhage. There is no comparative study regarding the effectiveness of this strategy in the literature. Our results could not lead to the conclusion that PSIAE is a useful tool for the total reduction of intraoperative blood loss during the resection of hemangioma. PSIAE may have prevented arterial bleeding related with hemangiomas, but portal bleeding which is inherent to hepatic surgery could still be a problem. Furthermore, the location and surgical approach to the embolized cases were different than the control cases. However, with the PSIAE application, which was practiced with a low complication rate, unnecessary dissection of the hepatic hilus for the control of hepatic artery before parenchymal dissection is omitted. Additionally, the median blood loss in the PSIAE group consisting of cases with hemangiomas in difficult surgical locations was found comparable with the non-PSIAE group consisting of cases in easy surgical locations. It must be noted that the overall amount of blood loss was less than the reported amounts in the literature indicating our competency in the surgical technique. Finally, slightly higher morbidity in the PSIAE group may also be related with surgical difficulties in that group.

We observed a statistically significant increase in bilirubin levels in the embolization group. This may be related to some unintentional parenchymal embolization during the procedure. Intrahepatic biliary tree is generally shifted due to mass effect of hemangiomas. This close relationship with biliary structures and hemangioma may be responsible for self-limited bilirubin elevation after PSIAE. During the follow-up period, we did not observe ischemic cholangitis, ischemic cholecystitis, pyogenic liver abscess, or focal biliary or hepatic necrosis with or without biliary sepsis. Those biliary complications are well-described as main complications (1.4%–60%) related to hepatic arterial embolization (40–43). However, most patients displaying biliary complications after hepatic arterial embolization have extensive parenchymal diseases, like hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Additionally, sequential hepatic arterial embolization sessions are generally required in the treatment protocol of these patients. We may need a longer follow-up period to get a healthy opinion on the long-term biliary effects of PSIAE in patients with normal liver parenchyma.

Another statistically significant difference between our groups was the hospital stay. It was inherently longer in the PSIAE group because of an extra procedure and a waiting time of three days after embolization. If the time required for PSIAE is excluded, the length of hospital stay would be comparable between the groups.

There are some limitations in this study. Main limitations are the small sample size and the retrospective design. The effects of comprehensive comorbidities on the development of complications may not be demonstrated clearly in such a small study population. Finally, absence of randomization in selection of patients may have caused a selection bias.

In conclusion, our results suggest that PSIAE reduces intraoperative blood loss in surgically challenging cases, comparable to cases having a low risk of blood loss operated without PSIAE. This procedure avoids unnecessary dissection of the hepatic hilus for the control of hepatic artery before parenchymal dissection. Additionally, PSIAE is a safe procedure with low morbidity. However, there will be a slight increase in hospital stay due to this additional procedure.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Ishak KG, Rabin L. Benign tumors of the liver. Med Clin North Am. 1975;59:995–1013. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)31998-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.mcg.0000159226.63037.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi BY, Nguyen MH. The diagnosis and management of benign hepatic tumors. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:401–412. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000159226.63037.a2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reddy KR, Kligerman S, Levi J, et al. Benign and solid tumors of the liver: relationship to sex, age, size of tumors, and outcome. Am Surg. 2001;67:173–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buell JF, Tranchart H, Cannon R, Dagher I. Management of benign hepatic tumors. Surg Clin N Am. 2010;90:719–735. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2010.04.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.suc.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strosberg JR, Choi J, Cantor AB, Kvols LK. Selective hepatic artery embolization for treatment of patients with metastatic carcinoid and pancreatic endocrine tumors. Cancer Control. 2006;13:72–78. doi: 10.1177/107327480601300110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Topaloglu S, Inci I, Calik A, et al. Intensive pulmonary care after liver surgery: a prospective survey from a single center. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:986–992. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.02.082. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.02.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Topaloglu S, Calik KY, Calik A, et al. Efficacy and safety of hepatectomy performed with intermittent portal triad clamping with low central venous pressure. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:297971. doi: 10.1155/2013/297971. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/297971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bismuth H, Houssin D, Castaing D. Major and minor segmentectomies-reglees-in liver surgery. World J Surg. 1982;6:10–24. doi: 10.1007/BF01656369. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01656369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baer HU, Dennison AR, Mouton W, Stain SC, Zimmermann A, Blumgart LH. Enucleation of large hemangiomas of the liver. Technical and pathologic aspects of a neglected procedure. Ann Surg. 1992;216:673–676. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199212000-00009. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00000658-199212000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagorney DM. Enucleation for giant liver haemangioma. HPB Surg. 1994;8:67–69. doi: 10.1155/1994/83792. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/1994/83792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alper A, Ariogul O, Emre A, Uras A, Okten A. Treatment of liver hemangiomas by enucleation. Arch Surg. 1988;123:660–661. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400290146027. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400290146027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarmiento JM, Que FG, Nagorney DM. Surgical outcomes of isolated caudate lobe resection: A single series of 19 patients. Surgery. 2002;132:697–709. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.127691. http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/msy.2002.127691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnelldorfer T, Ware AL, Smoot R, Schleck CD, Harmsen WS, Nagorney DM. Management of giant hemangioma of the liver: resection versus observation. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:724–730. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.08.006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Belghiti J, Vilgrain V, Paradis V. Benign liver lesions. In: Blumgart LH, editor. Surgery of the liver, biliary tract, and pancreas. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2007. pp. 1131–1151. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4160-3256-4.50083-1. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon SS, Charny CK, Fong Y, et al. Diagnosis, management and outcomes of 115 patients with hepatic hemangioma. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:392–402. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00420-4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00420-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaspar L, Mascarenhas F, da Costa MS, Dias JS, Afonso JG, Silvestre ME. Radiation therapy in the unresectable cavernous hemangioma of the liver. Radiother Oncol. 1993;29:45–50. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(93)90172-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0167-8140(93)90172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao J, Ke S, Ding XM, Zhou YM, Qian XJ, Sun WB. Radiofrequency ablation for large hepatic hemangiomas: initial experience and lessons. Surgery. 2013;153:78–85. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.06.004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hinshaw JL, Laeseke PJ, Weber SM, Lee FT., Jr Multiple-electrode radiofrequency ablation of symptomatic hepatic cavernous hemangioma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:146–149. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0750. http://dx.doi.org/10.2214/AJR.05.0750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li G, Wang Z, Yang S, Sun X, Chen M. A study on histogenesis of cavernous hemangioma of the liver. Chin J Exp Surg. 1997;1:20–21. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li GW, Chen QL, Jiang JT, Zhao ZR. The origin of blood supply for cavernous hemangioma of the liver. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2003;2:367–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reading NG, Forbes A, Nunnerley HB, Williams R. Hepatic hemangioma: a critical review of diagnosis and management. QJ Med. 1988;67:431–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng Q, Li Y, Chen Y, Ouyang Y, He X, Zhang H. Gigantic cavernous hemangioma of the liver treated by intra-arterial embolization with pingyangmycin-lipiodol emulsion: a multi-center study. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2004;27:481–485. doi: 10.1007/s00270-003-2754-2. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00270-003-2754-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Srivastava DN, Gandhi D, Seith A, Pande GK, Sahni P. Transcatheter arterial embolization in the treatment of symptomatic cavernous hemangiomas of the liver: a prospective study. Abdom Imaging. 2001;26:510–514. doi: 10.1007/s00261-001-0007-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00261-001-0007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou JX, Huang JW, Wu H, Zeng Y. Successful liver resection in a large hemangioma with intestinal obstruction after embolization. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2974–2978. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i19.2974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vassiou K, Rountas H, Liakou P, Arvanitis D, Fezoulidis I, Tepetes K. Embolization of a giant hepatic hemangioma prior to urgent liver resection. Case report and review of the literature. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:800–802. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9057-y. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00270-007-9057-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Panis Y, Fagniez PL, Cherqui D, Roche A, Schaal JC, Jaeck D. Successful arterial embolization of giant liver haemangioma. HPB Surg. 1993;7:141–146. doi: 10.1155/1993/76519. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/1993/76519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giavroglou C, Economou H, Ioannidis I. Arterial embolization of giant hepatic hemangiomas. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2003;26:92–96. doi: 10.1007/s00270-002-2648-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00270-002-2648-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kayan M, Çetin M, Aktafl AR, Yılmaz O, Ceylan E, Eroğlu HE. Pre-operative arterial embolization of symptomatic giant hemangioma of the liver. Prague Medical Report. 2012;113:166–171. doi: 10.14712/23362936.2015.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Djindjian R, Merland JJ, Rey A, Thurel J, Houdart R. Superselective arteriography of the external carotid artery. Importance of this new technic in neurological diagnosis and in embolization. Neurochirurgie. 1973:165–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brismar J, Conqvist S. Therapeutic embolization in the external carotid artery region. Acta Radiol Diagn. 1978;19:715–731. doi: 10.1177/028418517801900502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuroiwa T, Tanaka H, Ohta T, Tsutsumi A. Preoperative embolization of highly vascular brain tumors: clinical and histopathological findings. Noshuyo Byori. 1996;13:27–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozden I, Emre A, Alper A, et al. Long-term results of surgery for liver hemangiomas. Arch Surg. 2000;135:978–981. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.135.8.978. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.135.8.978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Popescu I, Ciurea S, Brasoveanu V, et al. Liver hemangioma revisited: current surgical indications, technical aspects, results. Hepatogastroenterol. 2001;48:770–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamaloglu E, Altun H, Ozdemir A, Ozenc A. Giant liver hemangioma: therapy by enucleation or liver resection. World J Surg. 2005;29:890–893. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-7661-z. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00268-005-7661-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Russo MW, Johnson MW, Fair JH, Brown RS., Jr Orthotopic liver transplantation for giant hepatic hemangioma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1940–1941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chui AK, Vass J, McCaughan GW, Sheil AG. Giant cavernous haemangioma: a rare indication for liver transplantation. ANZ J Surg. 1996;66:122–124. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1996.tb01132.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.1996.tb01132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xia F, Lau WY, Qian C, Wang S, Ma K, Bie P. Surgical treatment of giant liver hemangiomas: enucleation with continuous occlusion of hepatic artery proper and intermittent Pringle maneuver. World J Surg. 2010;34:2162–2167. doi: 10.1007/s00268-010-0592-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00268-010-0592-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Birincioglu I, Topaloglu S, Turan N, et al. Detailed dissection of hepato-caval junction and suprarenal inferior vena cava. Hepatogastroenterol. 2011;58:311–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Odorico JS, Hakim MN, Becker YT, et al. Liver transplantation as definitive therapy for complications after arterial embolization for hepatic manifestations of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Liver Transplant Surg. 1998;4:483–490. doi: 10.1002/lt.500040609. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/lt.500040609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chavan A, Caselitz M, Gratz KF, et al. Hepatic artery embolization for treatment of patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia and symptomatic hepatic vascular malformations. Eur Radiol. 2004;14:2079–2085. doi: 10.1007/s00330-004-2455-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00330-004-2455-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chavan A, Luthe L, Gebel M, et al. Complications and clinical outcome of hepatic artery embolisation in patients with hereditary haemrrhagic telangiectasia. Eur Radiol. 2013;23:951–957. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2694-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00330-012-2694-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mezhir JJ, Fong Y, Fleischer D, et al. Pyogenic abscess after hepatic artery embolization: a rare but potentially lethal complication. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:177–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.10.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]