Abstract

PURPOSE

The aim of this study was to investigate the feasibility of using acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) imaging to diagnose acute appendicitis.

METHODS

Abdominal ultrasonography (US) and ARFI imaging were performed in 53 patients that presented with right lower quadrant pain, and the results were compared with those obtained in 52 healthy subjects. Qualitative evaluation of the patients was conducted by Virtual Touch™ tissue imaging (VTI), while quantitative evaluation was performed by Virtual Touch™ tissue quantification (VTQ) measuring the shear wave velocity (SWV). The severity of appendix inflammation was observed and rated using ARFI imaging in patients diagnosed with acute appendicitis. Alvarado scores were determined for all patients presenting with right lower quadrant pain. All patients diagnosed with appendicitis received appendectomies. The sensitivity and specificity of ARFI imaging relative to US was determined upon confirming the diagnosis of acute appendicitis via histopathological analysis.

RESULTS

The Alvarado score had a sensitivity and specificity of 70.8% and 20%, respectively, in detecting acute appendicitis. Abdominal US had 83.3% sensitivity and 80% specificity, while ARFI imaging had 100% sensitivity and 98% specificity, in diagnosing acute appendicitis. The median SWV value was 1.11 m/s (range, 0.6–1.56 m/s) for healthy appendix and 3.07 m/s (range, 1.37–4.78 m/s) for acute appendicitis.

CONCLUSION

ARFI imaging may be useful in guiding the clinical management of acute appendicitis, by helping its diagnosis and determining the severity of appendix inflammation.

Acute appendicitis is among the most common causes of acute abdominal pain (1, 2). Despite significant improvements in medical technology, the diagnosis of appendicitis is typically based on clinical findings, resulting in a false-positive rate of 8%–30% (3–6). It is widely understood that ultrasonography (US) and computed tomography (CT) are effective imaging modalities in the detection of appendicitis, although certain limitations to both techniques are apparent. Namely, visualization of the appendix is impossible in nearly 15% of healthy people, and among patients with suspected appendicitis, detection of tip appendicitis or periappendiceal inflammation is relatively poor (7–11). Previous studies employing graded-compression US reported widely variable rates of diagnostic accuracy, with sensitivity ranging from 44% to 100% and specificity ranging from 47% to 99% (12).

The use of scoring systems enhances the sensitivity and specificity of the available imaging modalities in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. In addition, scoring systems aim to minimize the risk of clinical complications and avoid the costs associated with delayed diagnosis or unnecessary appendectomies. Among current scoring systems, the Alvarado system has proven to be a cost-effective method of classifying patients according to acute appendicitis risk. The efficacy of the Alvarado system has been demonstrated in clinical studies, which identified a diagnostic cutoff score of 4–6 for acute appendicitis. Appendectomy is strongly indicated among patients with a score of ≥7, while patients scoring 5 or 6 should receive follow-up care (13). However, the sensitivity and specificity of the Alvarado system do not exceed 90%.

The mechanical properties of a tissue can be determined using acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) imaging. The technique of ARFI imaging comprises two different methods: Virtual Touch™ tissue imaging (VTI) and Virtual Touch™ tissue quantification (VTQ). VTI provides a qualitative map (elastogram) of relative stiffness for a user-defined region of interest. Using this method, stiff tissue may be differentiated from soft tissue even if it is appearing isoechoic using conventional US imaging. VTQ is a modified application of US ARFI imaging that generates shear wave velocity (SWV) corresponding to tissue stiffness. VTQ has been used to determine tissue elasticity of a variety of organ systems, inflammatory processes, congestion, and fibrosis. ARFI imaging capability is an integral component of the existing US equipment and may be performed as a part of standard US procedures. SWV can be quantified through the application of standard B-mode US. Recent data demonstrated a strong correlation between ARFI imaging and hepatic fibrosis staging (6–8), and investigations of renal tumor diagnosis have also been conducted (14–17). The diagnosis of acute appendicitis by quantitative real-time elastography has been previously reported, although clinical data demonstrating the efficacy of the technique in a substantial number of patients is lacking (18). The aim of the present study was to evaluate the efficacy of ARFI imaging in diagnosis of acute appendicitis.

Methods

A total of 53 patients presenting with abdominal pain in the right lower quadrant from February through August 2013 were studied. The control group consisted of 52 age- and sex-matched healthy persons with a body mass index (BMI) <30 kg/m2 and a visible appendix upon US examination. The Alvarado score was calculated for all patients. Exclusion criteria included BMI >30 kg/m2 and history of right lower abdominal surgery. The study excluded two pregnant patients and five obese patients due to an inability to visualize the appendix. All clinicians and sonographers were blinded to the study group designation. Demographic data, clinical symptoms, imaging data, operative findings, pathology reports and Alvarado scores were assessed in all study participants. Written consent was obtained from all study participants. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the University Review Board. Radiologic evaluations were performed by a single radiologist (C.G.) with 13 years of US experience.

Prospective calculation of the Alvarado score was completed for all patients presenting with right lower abdominal pain. The Alvarado system incorporates multiple scoring parameters including migrating pain and tenderness in the right iliac fossa, anorexia, vomiting and nausea, rebound pain, elevated temperature, and leukocyte and neutrophil counts (Table 1). An Alvarado score of <7 is designated as “low”, while a score of ≥7 is considered “high” and indicates the presence of acute appendicitis.

Table 1.

The Alvarado scoring system (strong recommendation for appendectomy ≥7 points)

| Features | Score |

|---|---|

| Symptoms | |

| Migratory right iliac fossa pain | 1 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 1 |

| Anorexia | 1 |

| Physical exam signs | |

| Tenderness in right iliac fossa | 2 |

| Rebound tenderness in right iliac fossa | 1 |

| Elevated temperature | 1 |

| Laboratory findings | |

| Leukocytosis | 2 |

| Left shift of neutrophils | 1 |

| Total score | 10 |

Standard US and ARFI imaging was performed using a convex transducer (4 MHz) followed by a linear transducer (9 MHz), utilizing a graded compression technique (Acuson S2000; Siemens, California, USA). US findings consistent with acute appendicitis included the presence of a rounded, noncompressible appendix of >6 mm in diameter, wall thickness >3 mm, and periappendiceal fluid and enhanced echogenicity in the adjacent adipose tissue.

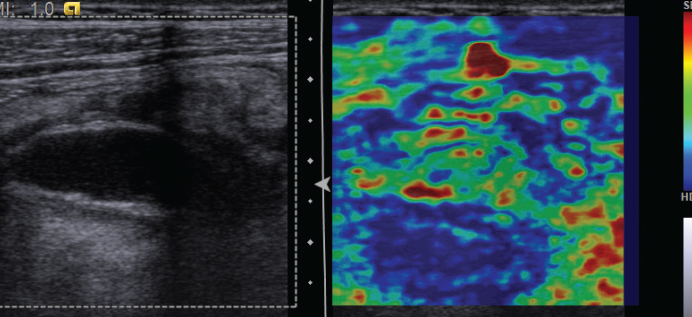

The appendix and periappendiceal tissues were evaluated using ARFI imaging, VTI, and VTQ in all study subjects. VTI color scoring system was used to discriminate between normal appendix (red) and the presence of appendicitis (yellow-green or blue-purple). VTI was used to classify periappendiceal inflammation as mild, moderate, or severe. Mild inflammation was represented by regions of enhanced stiffness adjacent to a blue-purple appendix. Periappendiceal inflammation extending within 2 cm from the outer wall of the appendix was indicative of moderate inflammation. Marked inflammation was reported if inflammation exceeded 2 cm beyond the appendix wall. Appendectomy was conducted in all patients following a positive diagnosis, and the surgical findings were used to confirm the VTI findings. The surgical report detailed the total mass of the appendix, the presence of inflammation and hyperemia in the intestinal wall, the presence or absence of appendicoliths, the omentum and mesoappendix appearance, the presence or absence of periappendiceal adhesions and inflammation, and the presence of regional fluid. The details of the surgical report were later correlated with VTI findings. Three independent reviewers determined the ARFI inflammatory designation. SWV values of patients with acute appendicitis were correlated with the Alvarado and disease severity scores.

Statistical analysis of the study data was completed using SPSS for Windows version 15.0. The normal distribution of the variables was tested using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated from the comparative diagnostic data. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was performed. The Pearson’s chi-square test, Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal Wallis and McNemar tests were applied in the comparison of categorical and continuous variables. The threshold of statistical significance was established at P < 0.05. Correlations were evaluated with Spearman’s correlation coefficient.

Results

The patient group included 53 patients (28 male and 25 female) with a median age of 21 years (range, 7–64 years). The control group included 52 healthy persons (23 male and 29 female) with a median age of 23 years (range, 9–66 years). There was no statistically significant difference between the patient and control groups in terms of age and gender (P = 0.131 and P = 0.378). BMI was 27.5±2.50 kg/m2 in the patient group and 26.2±3.32 kg/m2 in the control group.

Upon US examination, the appendix had a diameter <6 mm and formed a compressible tube in all control subjects. Normal appendix tissue was visualized in red using VTI and the color scoring consisted of minimal yellow and green. The median appendix SWV was 1.11 m/s (range, 0.6–1.56 m/s) in the control group. Appendix diameter was >6 mm in patients with acute appendicitis, and the appendix wall was swollen and uncompressible, with a tubular structure and an apendicolith filled with periappendiceal liquid. VTI color-coding consisted largely of green-blue, blue, and dark blue. The median SWV value was 3.07 m/s, (range, 1.37–4.78 m/s) among patients with acute appendicitis.

Histopathologic analysis confirmed the following specific diagnoses in specimens obtained from the resected tissue in the patient group: phlegmonous appendicitis (n=15), perforated appendicitis (n=2), plastroned appendicitis (n=5), appendicitis (n=22), gangrenous appendicitis (n=1), tip appendicitis (n=3), lymphadenitis (n=2), cecal diverticulitis (n=1), and colitis (n=2).

According to the pathological results of the 48 positive patients, the Alvarado scores were <7 in 14 patients (29.2%) and ≥7 in 34 patients (70.8%); of five negative patients, one (20%) scored <7 and four (80%) scored ≥7. However, these results did not correlate with the histopathological results (r=0.059, P = 0.031). The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of the Alvarado scoring were 70.8%, 20%, 89.5%, and 6.7%, respectively, as determined by correlation with the histopathological findings. Both ARFI imaging and histopathological findings confirmed the extent of appendiceal and periappendiceal inflammation in 34 patients with Alvarado score ≥7. SWV values of appendix according to Alvarado scores in acute appendicitis patients are shown in Table 2. ARFI imaging facilitated the successful diagnosis in 14 out of 19 patients receiving an indeterminate Alvarado score <7. A total of four appendixes were declared normal by ARFI imaging examination, and this diagnosis was confirmed by histopathological examination. ARFI imaging resulted in a single false-positive diagnosis corresponding to a case of cecal diverticulitis.

Table 2.

Mean SWV values of appendix according to Alvarado scores in suspected cases of acute appendicitis (n=53)

| Alvarado score | n | SWV (m/s) mean±SD (range) |

|---|---|---|

| Score 4 | 6 | 3.19±0.26 (2.45–4.09) |

| Score 5 | 10 | 2.49±0.24 (1.53–3.74) |

| Score 6 | 8 | 2.39±0.36 (1.16–3.88) |

| Score 7 | 9 | 2.52±0.24 (1.68–3.53) |

| Score 8 | 11 | 3.19±0.16 (2.34–4.16) |

| Score 9 | 9 | 3.41±0.40 (1.37–4.78) |

SWV, shear wave velocity; SD, standard deviation.

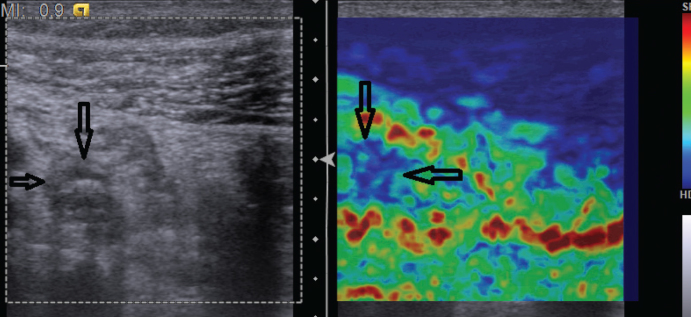

Appendicitis was diagnosed in 41 of 53 patients after US evaluation. Histopathological analysis confirmed the diagnosis of appendicitis in 40 of these patients. US revealed no evidence of appendicitis in the remaining 12 patients. However, histopathological analysis demonstrated the presence of appendicitis in eight patients. Among patients with false-negative US three patients had tip appendicitis and five patients had inflammation of the appendix with a diameter <6 mm (Fig. 1). Among patients with true-negative US, two patients had lymphadenitis and two patients had colitis. US showed 83.3% sensitivity, 80% specificity, 97.6% PPV, and 33.3% NPV in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis.

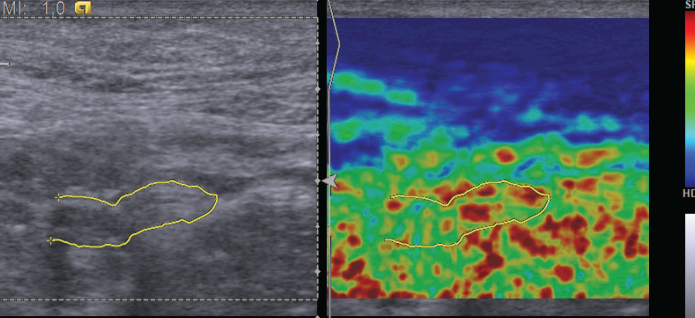

Figure 1.

Sonogram (left) showing an ovoid appendix with collapsed lumen, and elastogram (right) showing normal stiffness of the appendicular wall in yellow, green, and red.

ARFI imaging accurately identified all patients with acute appendicitis. ARFI imaging detected the presence of inflammation in a single patient ultimately diagnosed with cecal diverticulitis and in eight patients that were incorrectly identified as normal during US examination due to an appendix diameter <6 mm. For these eight patients, ARFI imaging revealed increased appendix wall stiffness and SWV >1.82 m/s (Figs. 2–6). ARFI imaging showed 100% sensitivity, 98% specificity, 98% PPV, and 100% NPV, in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis (P < 0.01). No correlation was detected between SWV and the Alvarado scoring (r=0.251, P = 0.069). SWV was significantly different among patients with different disease severity, as identified by ARFI (Table 3). Specifically, ARFI imaging identified 14 patients with mild, 12 patients with moderate, and 22 patients with severe appendix wall stiffness. Among patients identified as having severe appendix wall stiffness, 15 demonstrated the presence of phlegmon, five exhibited plastron, and two suffered from perforation. Disease stratification according to VTI findings moderately correlated with surgical findings (r=0.539, P < 0.001).

Figure 2.

Sonogram (left) showing a distended appendix, and elastogram (right) showing increased appendicular stiffness in blue (arrows) (severity stage 1).

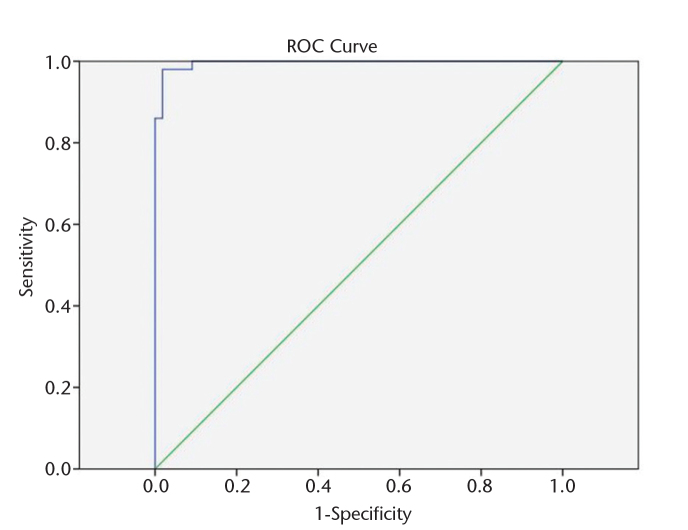

Figure 6.

ROC analysis of SWV in patient and control groups. Cutoff value, 1.82 m/s; area under the curve, 0.998; P < 0.001 (95% CI, 0.993–1.000).

Table 3.

Surgical results and SWV in acute appendicitis patients of different severity and in healthy controls

| Severity | n | Sugical results | SWV (m/s) median (range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control group | 50 | 1.1 (0.6–1.56) | |

| Patients | |||

| Stage 1 | 14 | Tip appendicitis (n=3) Appendicitis (n=11) |

2.56 (1.18–3.87) |

| Stage 2 | 12 | Gangrenous appendicitis (n=1) Appendicitis (n=11) |

2.5 (1.37–4.78) |

| Stage 3 | 22 | Phlegmonous appendicitis (n=15) Perforated appendicitis (n=2) Plastroned appendicitis (n=5) |

3.38 (1.68–4.30) |

P < 0.001, for control group vs. stages 1, 2, and 3; P = 0.526, for stage 1 vs. stage 2; P = 0.101, for stage 1 vs. stage 3; P = 0.020, for stage 2 vs. stage 3.

SWV, shear wave velocity.

Discussion

The results of the present study suggest that the Alvarado system is inferior to modern imaging methods in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Our data indicate 70.8% sensitivity, 20% specificity, 89.5% PPV, and 6.7% NPV, using the Alvarado system. A previous study has reported sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV values of 84.2%, 66.7%, 94.1%, and 40%, respectively, for the Alvarado scoring system (19).

US is a rapid, cost-effective, and accurate imaging modality for the definitive diagnosis of acute appendicitis. In comparison to other imaging methods, US is a painless, noninvasive, practical, and radiation-free procedure that requires minimal preparation. Prior publications report the sensitivity of US in the detection of acute appendicitis as 94%–100% (20, 21). Our study shows that US has 83.3% sensitivity and 80% specificity in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. However, US is ineffective in the diagnosis of appendicitis when the diameter of the appendix is <6 mm, corresponding to 15% of appendicitis cases (22). Technological advances permit the visualization of the appendix in 88% of healthy subjects; however, differentiation between healthy and inflamed tissue is difficult when the diameter is <6 mm (23). In the present study, acute appendicitis was successfully diagnosed by ARFI imaging based on green-blue, blue, and dark blue color-coding in VTI and SWV >1.82 m/s, even when the appendix diameter was <6 mm.

No single US finding allows for perfect discrimination between the normal and diseased appendix. Thus, the combination of multiple techniques is necessary for reliable diagnosis of appendicitis (24, 25). Mild inflammation of the appendix may be undetectable by US, particularly when the appendix is not distended, as occurred in five patients included in the present study. CT may be preferred as a method requiring less technical experience and minimizing patient discomfort (26, 27). CT allows for more accurate determination of the degree of inflammation of the appendix relative to US (28). However, exposure to ionizing radiation prevents the use of CT in pregnant women, young adults, and children (29).

MRI is more sensitive (97%–100%) and more specific (92%–93%) in identifying appendicitis, but its high cost limits access to this technology for most patients (30). Notably, real-time elastography has demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity in diagnosing acute appendicitis through the qualitative evaluation of wall stiffness in the inflamed appendix (18). In the present study, VTI and VTQ were utilized in combination to measure appendix wall stiffness both qualitatively and quantitatively. These modalities were highly advantageous for the differentiation between healthy and inflamed tissue, in cases involving normal appendix diameter (n=5) or tip appendicitis (n=3).

A recent study evaluated inflammation of the periappendiceal adipose tissue in acute appendicitis, as indicated by changes in echogenicity in US imaging (28). However, these parameters may be better assessed using elastography. ARFI imaging can also be used to classify the degree of appendix and periappendiceal inflammation as mild, moderate, and severe. ARFI imaging identified periappendiceal inflammation in the present study, revealing characteristics of appendiceal phlegmon, plastron, and perforation. As such, ARFI imaging may be an important tool in evaluating acute appendicitis in its earliest stages, as well as in advanced stages when the risk of perforation is greatest. ARFI imaging showed 100% sensitivity, 98% specificity, 98% PPV, and 100% NPV, in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis. Increases in the size and severity of inflammation are presumed to progressively increase SWV. Disease stratification according to VTI findings was significantly correlated with surgical findings.

In clinical practice, US is the method of choice for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis, despite better sensitivity and specificity associated with CT and MRI. However, ARFI imaging can be used to increase the diagnostic efficacy of US, enabling earlier diagnosis of appendicitis. As such, ARFI imaging may prevent unnecessary operations among patients with high Alvarado scores. Moreover, ARFI imaging may ultimately contribute to a reduction in the incidence of complications resulting from the late diagnosis of appendicitis among patients with low Alvarado scores. Diagnosis of appendicitis with ARFI imaging may enable rapid and accurate diagnosis of appendicitis in cases with reduced inflammation, such as nondistended and tip appendicitis. Overall, diagnostic sensitivity is remarkably improved with the combined use of US imaging. Thus, ARFI imaging facilitates the rapid implementation of appropriate clinical management strategies. However, certain technical limitations apply to ARFI imaging, including the inability to assess an appendix that cannot be visualized using B-mode US. Additionally, similar to standard US, elastography requires considerable cooperation from the patient. External pressure applied during probe application may influence ARFI imaging measurements. Elastography may indicate increased stiffness forming secondarily as a result of inflammation in the right lower quadrant. If no appendicitis is present, ARFI imaging is unable to differentiate between multiple potential causes of increased stiffness in the lower right abdomen.

A limitation of the study was the use of a healthy control group without any complaints. A more appropriate control group might consist of patients with right lower quadrant pain originating as a result of alternate etiologies. Other inflammatory conditions of the bowels and colon, such as diverticulitis and terminal ileitis, may also present with increased stiffness mimicking appendicitis on elastography. The heterogeneous nature of structures in the right lower abdomen makes the measurement of SWV challenging and may limit the reproducibility of our results. Difficulties visualizing the appendix in obese individuals may limit the application of ARFI imaging in the evaluation of a subset of appendicitis cases. It is assumed that early diagnosis and treatment of tip appendicitis and acute appendicitis with mild inflammation is advantageous and would result in decreased complication rates, although this assumption cannot be substantiated by currently available data.

In conclusion, combined application of US and ARFI increases sensitivity while maintaining comparable specificity in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis, relative to US alone. Furthermore, ARFI imaging is an effective means for determining the severity of acute inflammation of the appendix with obvious utility in guiding the clinical management.

Figure 3.

Sonogram (left) showing a distended appendix with surrounding fluid, and elastogram (right) showing marked periappendicular inflammation (surgery revealed a perforated appendicitis; severity stage 3).

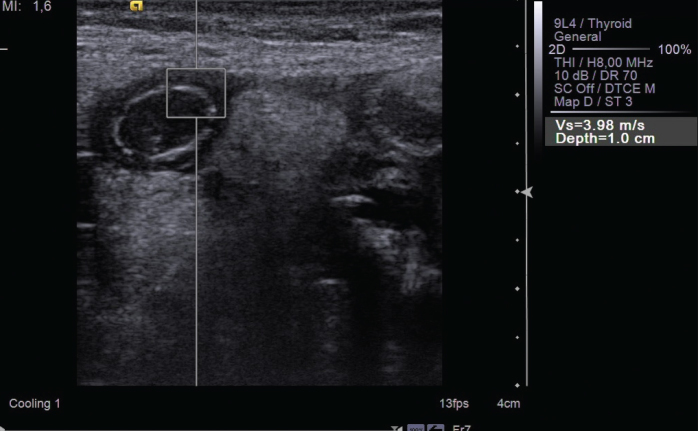

Figure 4.

Increased SWV value in acute appendicitis.

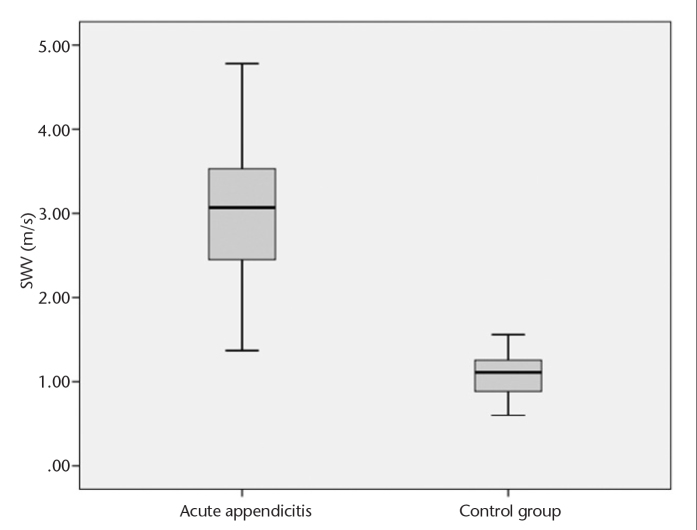

Figure 5.

Box plot showing comparison of SWV between patient and control groups. Median SWV is significantly different between groups according to Mann-Whitney U test (P < 0.001).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Birnbaum BA, Wilson SR. Appendicitis at the millennium. Radiology. 2000;215:337–348. doi: 10.1148/radiology.215.2.r00ma24337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalazonitis AN, Tzovara I, Sammouti E, et al. CT in appendicitis. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2008;14:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bursali A, Araç M, Oner AY, Celik H, Ekşioğlu S, Gümüş T. Evaluation of the normal appendix at low-dose non-enhanced spiral CT. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2005;11:45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips RL, Jr, Bartholomew LA, Dovey SM, Fryer GE, Jr, Miyoshi TJ, Green LA. Learning from malpractice claims about negligent, adverse events in primary care in the United States. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13:121–126. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2003.008029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selbst SM, Friedman MJ, Singh SB. Epidemiology and etiology of malpractice lawsuits involving children in US emergency departments and urgent care centers. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2005;21:165–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lane MJ, Liu DM, Huynh MD, Jeffrey RB, Jr, Mindelzun RE, Katz DS. Suspected acute appendicitis: nonenhanced helical CT in 300 consecutive patients. Radiology. 1999;213:341–346. doi: 10.1148/radiology.213.2.r99nv44341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rettenbacher T, Hollerweger A, Macheiner P, et al. Ovoid shape of the vermiform appendix: a criterion to exclude acute appendicitis—evaluation with US. Radiology. 2003;226:95–100. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2261011496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puig S, Hörmann M, Rebhandl W, Felder-Puig R, Prokop M, Paya K. US as a primary diagnostic tool in relation to negative appendectomy: six years experience. Radiology. 2003;226:101–104. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2261011612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaiser S, Frenckner B, Jorulf HK. Suspected appendicitis in children: US and CT—a prospective randomized study. Radiology. 2002;223:633–638. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2233011076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazeh H, Epelboym I, Reinherz J, Greenstein AJ, Divino CM. Tip appendicitis: clinical implications and management. Am J Surg. 2009;197:211–215. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nikolaidis P, Hwang CM, Miller FH, Papanicolaou N. The nonvisualized appendix: incidence of acute appendicitis when secondary inflammatory changes are absent. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:889–892. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.4.1830889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pinto F, Pinto A, Russo A, et al. Accuracy of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in adult patients: review of the literature. Crit Ultrasound J. 2013;5(Suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/2036-7902-5-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yildirim E, Karagülle E, Kirbaş I, et al. Alvarado scores and pain onset in relation to multislice CT findings in acute appendicitis. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2008;14:14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goertz RS, Amann K, Heide R, Bernatik T, Neurath MF, Strobel D. An abdominal and thyroid status with Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse Elastometry- A feasibility study Acoustic Force Impulse Elastometry of human organs. Eur J Radiol. 2011;80:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fahey BJ, Nelson RC, Bradway DP, Hsu SJ, Dumont DM, Trahey GE. In vivo visualization of abdominal malignancies with acoustic radiation force elastometry. Phys Med Biol. 2008;53:279–293. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/53/1/020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gallotti A, D’Onofrio M, Pozzi Mucelli R. Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse (ARFI) ultrasound technique in virtual touch with quantification of the upper abdomen. Radiol Med. 2010;115:889–897. doi: 10.1007/s11547-010-0504-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heide R, Strobel D, Bernatik T, Goertz RS. Characterization of focal liver lesions (FLL) with acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) elastometry. Ultraschall Med. 2010;31:405–409. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1245565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kapoor A, Kapoor A, Mahajan G. Real-time elastography in acute appendicitis. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:871–877. doi: 10.7863/jum.2010.29.6.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inci E, Hocaoğlu E, Aydin S, Palabiyik F. Efficiency of unenhanced MRI in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis: comparison with Alvarado scoring system and histopathological results. Eur J Radiol. 2011;80:253–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2010.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu SH, Kim CB, Park JW, Kim MS, Radosevich DM. Ultrasonography in the diagnosis of appendicitis: evaluation by meta-analysis. Korean J Radiol. 2005;6:267–277. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2005.6.4.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sivit CJ. Imaging the child with right lower quadrant pain and suspected appendicitis: Current concepts. Pediatr Radiol. 2004;34:447–453. doi: 10.1007/s00247-004-1179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karabulut N, Boyaci N, Yagci B, Herek D, Kiroglu Y. Computed tomography evaluation of the normal appendix: comparison of low-dose and standard-dose unenhanced helical computed tomography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2007;31:732–40. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0b013e318033c7de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giuliano V, Giuliano C, Pinto F, Scaglione M. CT method for visualization of the appendix using a fixed oral dosage of diatrizoate--clinical experience in 525 cases. Emerg Radiol. 2005;11:281–285. doi: 10.1007/s10140-005-0414-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kouamé N, N’goan-Domoua AM, N’dri KJ, et al. The diagnostic value of indirect ultra-sound signs during acute adult appendicitis. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2012;93:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwerk WB, Wichtrup B, Rothmund M, Rüschoff J. Ultrasonography in the diagnosis of acute appendicitis: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:630–639. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90634-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puylaert JB. Ultrasound of the acute abdomen: gastrointestinal conditions. Radiol Clin North Am. 2003;41:1227–1242. doi: 10.1016/s0033-8389(03)00120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simonovsky V. Sonographic detection of normal and abnormal appendix. Clin Radiol. 1999;54:533–599. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(99)90851-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee MW, Kim YJ, Jeon HJ, Park SW, Jung SI, Yi JG. Sonography of acute right lower quadrant pain: importance of increased intraabdominal fat echo. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:174–179. doi: 10.2214/ajr.07.3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karabulut N, Kiroglu Y, Herek D, Kocak TB, Erdur B. Feasibility of low-dose unenhanced multi-detector CT in patients with suspected acute appendicitis: comparison with sonography. Clin Imaging. 2014;38:296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Avcu S, Çetin FA, Arslan H, Kemik Ö, Dülger AC. The value of diffusion-weighted imaging and apparent diffusion coefficient quantification in the diagnosis of perforated and nonperforated appendicitis. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2013;19:106–110. doi: 10.4261/1305-3825.DIR.6070-12.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]