Abstract

Schwannomatosis is characterized by the development of multiple non-vestibular, non-intradermal schwannomas. Constitutional inactivating variants in two genes, SMARCB1 and, very recently, LZTR1, have been reported. We performed exome sequencing of 13 schwannomatosis patients from 11 families without SMARCB1 deleterious variants. We identified four individuals with heterozygous loss-of-function variants in LZTR1. Sequencing of the germline of 60 additional patients identified 18 additional heterozygous variants in LZTR1. We identified LZTR1 variants in 43% and 30% of familial (three of the seven families) and sporadic patients, respectively. In addition, we tested LZTR1 protein immunostaining in 22 tumors from nine unrelated patients with and without LZTR1 deleterious variants. Tumors from individuals with LZTR1 variants lost the protein expression in at least a subset of tumor cells, consistent with a tumor suppressor mechanism. In conclusion, our study demonstrates that molecular analysis of LZTR1 may contribute to the molecular characterization of schwannomatosis patients, in addition to NF2 mutational analysis and the detection of chromosome 22 losses in tumor tissue. It will be especially useful in differentiating schwannomatosis from mosaic Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2). However, the role of LZTR1 in the pathogenesis of schwannomatosis needs further elucidation.

Introduction

Schwannomatosis (MIM 162091) is a tumor predisposition syndrome characterized by the development of multiple intracranial, spinal and peripheral schwannomas, without involvement of the vestibular nerve, which is pathognomonic of Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2; MIM 101000).1,2 NF2 and schwannomatosis patients share common clinical features; however, germline NF2 gene mutations are not identified in schwannomatosis patients. In 1996, schwannomatosis was recognized as a distinct clinical entity from NF23 by the molecular analysis of tumors from schwannomatosis patients: schwannomatosis-associated schwannomas frequently harbor inactivating variants of the NF2 gene and loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of 22q, exclusively in tumors. Therefore, the hallmark of schwannomatosis is different somatic variants in multiple tumors from the same patient.2

Schwannomatosis is a genetic condition, but for poorly understood reasons its occurrence does not follow common inheritance patterns. The majority of cases are sporadic with 15–25% of cases being inherited from an affected parent.4 The transmission risk can be assumed to be 50% in an individual with proven family history, but the risks for sporadic cases are less clear. In addition, non-penetrance has been described.4

In 2007, germline variants in the SMARCB1 gene, located on 22q centromeric to NF2, were identified in schwannomatosis patients, implicating it as the first predisposing gene for schwannomatosis.5 However, genetic studies demonstrated that constitutional variants in this gene occur only in 40–50% of familial cases and in 8–10% of sporadic cases.6, 7, 8, 9 Very recently, germline variants in a novel gene, LZTR1, were identified in 100% of familial cases and in about 70% of sporadic patients.10 LZTR1 is also located on 22q, centromeric to SMARCB1.

In SMARCB1- and LZTR1-related schwannomatosis, tumorigenesis follows the 4-hits/3-step model: the germline mutated SMARCB1 or LZTR1 gene, as well as the somatic NF2 variant, are retained in the tumor, whereas the other chromosome 22 (or at least a segment containing wild-type SMARCB1, LZTR1 or NF2) is lost.11

To further assess the clinical indications for LZTR1 molecular screening in medical genetics practice, we evaluated its involvement in the pathogenesis of a series of SMARCB1-unrelated schwannomatosis patients.

Materials and methods

Patients

Samples from schwannomatosis patients were collected at the Medical Genetics Unit of the University of Florence (Italy) and at the Department of Genome Analysis, Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam (the Netherlands). Clinical data of patients are shown in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The study was approved by the ethical committee of Careggi Hospital (protocol no. 0062368/2011).

Data of the study (variants and phenotypes) were submitted at the gene variant database (URL: http://lovd.nl/3.0/home) with patient IDs 17623–17625, 17628–17630 and 17632–17646.

Exome sequencing

DNA was extracted from blood and fresh tumor tissues, and sequence libraries were generated following standard Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA) protocols established in the UCLA Clinical Genomics Center for Clinical Exome Sequencing. The sample libraries were uniquely tagged and hybridized with capture oligonucleotides from the Agilent SureSelect 50 Mb All Exon capture kit to enrich for exons (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), and then sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq 2500.

Bioinformatic analysis

First, reads that pass Illumina quality filters were converted from qseq to fastq file format. Novoalign, using an index of the NCBI human genome reference build 37(HG37), produced a binary SAM (bam) file of aligned reads. PCR duplicates for all files were marked using Picard's MarkDuplicates command and ignored in downstream analysis.

Genome analysis toolkit (GATK) was used for variant calling.12,13 Quality scores generated by the sequencer were recalibrated to more closely represent the actual probability of mismatching the reference genome by analyzing the covariation among reported quality score, position within the read, dinucleotide and probability of a reference mismatch. Then, local realignment around small insertion/deletions (indels) was again performed, this time using GATK's indel realigner to minimize the number of mismatching bases across all the reads. This removes alignment artifacts that can cause false-positive single-nucleotide variations (SNVs). Statistically significant non-reference variants, SNVs and indels, were identified using the GATK unified genotyper. Using the GATK variant annotator, each identified SNV and indel was annotated with various statistics, including allele balance, depth of coverage, strand balance and multiple quality metrics. These statistics were then used to identify likely false-positive SNPs using the GATK variant quality score recalibrator (VQSR). Variants with a VQSR score under a chosen threshold were assumed to be false and filtered out, leaving a set of likely true variants.

After the variants were identified, an in-house variant annotator based on ENSEMBL (ensembl.org) was used to additionally annotate each variant with information including dbSNP ID, gene names and accession numbers, variant consequences, protein positions and amino-acid changes, conservation scores, HapMap frequencies, tissue-specific expression, Polyphen and SIFT predictions on the effect of the variant on protein function and clinical association.14 Novel (non-dbSNP) variants predicted to be protein damaging by Polyphen or SIFT were included for further analyses. Potentially causative variants were identified by filtering for damaging, heterozygous variants found in the affected patients and absent in unaffected family members.

High-resolution melting analysis

Blood DNAs were analyzed by high-resolution melting analysis (HRMA), performed on a Rotor Gene_6000 Instrument (Corbett Research, Sydney, Australia), followed by direct sequencing of amplicons showing an abnormal melting curve.

Sanger sequencing

All variants of interest, and the entire coding sequences of LZTR1, SMARCB1 and NF2, were sequenced with PCR and capillary sequencing. All primers were designed using Primer3Plus (http://primer3plus.com/web_3.0.0/primer3web_input.htm) and ordered from MWG-Biotech AG (Ebersberg, Germany). Primer sequences are available on request. Capillary sequencing was performed on Biosystems 3100 or 310 Capillary DNA Analyzer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Raw and analyzed sequence results were visualized on Sequence Scanner v1.0 (Life Technologies).

Variants were named according to the reference sequences NM_006767.3 (LZTR1) and NM_181832.2 (NF2). LZTR1 exons were numbered as in NG_034193.1.

Microsatellite analysis

LOH on 22q was investigated using microsatellites D22S420, D22S1174, D22S315, D22S1154, D22S1163, D22S280, D22S277 and D22S1169 from the ABI PRISM Linkage Mapping set version 2.5 (Life Technologies). PCR products were analyzed on a model 310 automated sequencer (Life Technologies); after electrophoresis, data were analyzed using GeneMapper software (Life Technologies).

Multiplex ligation probe amplification

Copy number changes (deletions or duplications) of SMARCB1, NF2 and LZTR1 loci and flanking genes were analyzed by Multiplex Ligation-Dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA) when fresh tumor tissues were available. SMARCB1, NF2 and 22q11 MLPA test kits (MRC-Holland, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; P044_B1, P258_C1 and P324_A2) were used and electrophoresis data were analyzed using GeneMapper software (Life Technologies).

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections (3 μm thick) were deparaffinized and rehydrated. Heat-induced epitope retrieval was performed with Dako (Glostrup, Denmark) target retrieval solution (pH 9) for 25 min at 98 °C. Slides were treated with 3% H2O2 in dH2O for 10 min and then incubated in 10% normal goat serum for 30 min. Incubation with the primary antibody against LZTR1 (NBP1-77121, Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA) was carried out for 1 h at room temperature (dilution 1/25) and with the secondary antibody (Biotinylated goat anti-rat, BA-1000, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 30 min at room temperature (dilution 1/2000). Biotin was detected using the Vectastain Elite ABC kit (PK-6100, Vector Laboratories) following the manufacturer's recommendations. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated and then mounted with xylene-based liquid mounting media.

In silico analysis

The following tools designed to provide splicing prediction were used: Human Splicing Finder (http://www.umd.be/HSF/),15 splice site prediction by neural network (NNSplice; http://www.fruitfly.org/seq_tools/splice.html)16 and Automated Splice Site and Exon Definition Analysis (ASSEDA) server (http://splice.uwo.ca).17

The predicted effects of missense variants on LZTR1 function were assessed using the following open access software: PolyPhen 2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/),18 SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org/www/SIFT_enst_submit.html),19 Mutation Taster (http://www.mutationtaster.org/)20 and ClustalW2 (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/clustalw2/index.html).21, 22, 23

Results

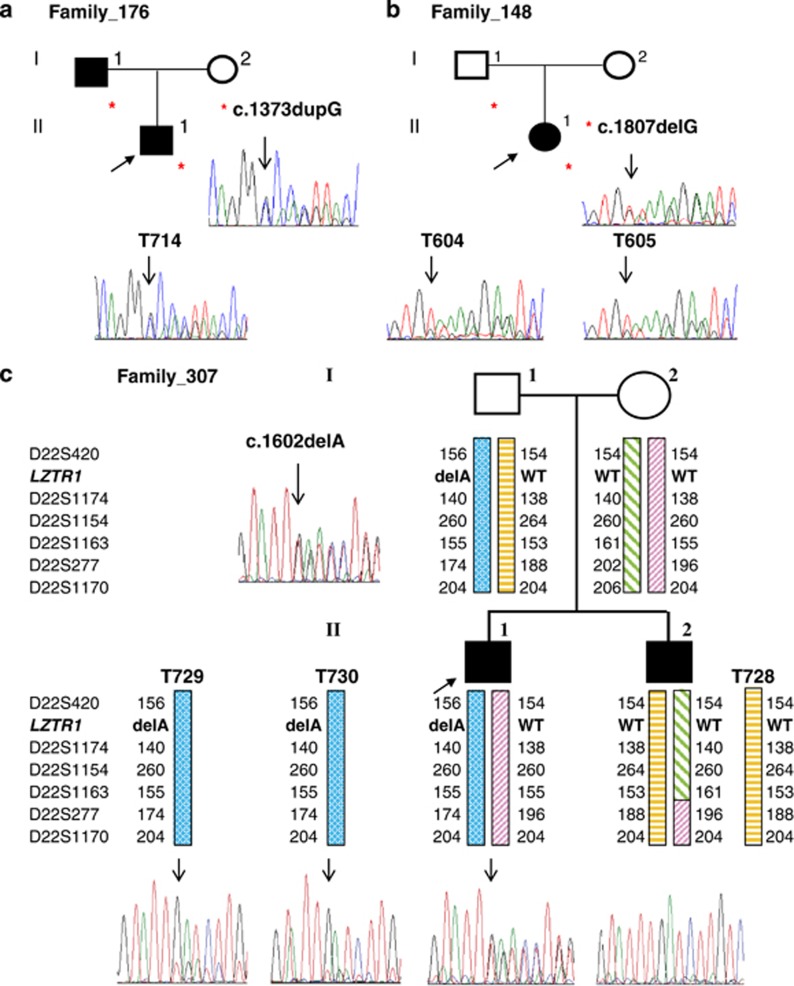

To identify additional determinants of schwannomatosis, we performed exome-sequencing analysis in 4 sporadic and 9 familial cases from 11 unrelated families with SMARCB1-unrelated schwannomatosis. Exome sequencing identified four deleterious variants of the LZTR1 gene in four unrelated families that were verified by Sanger sequencing (Table 1). The first variant identified in two affected members of family 176 was a frameshift variant in exon 13, c.1373dupG, which introduces a stop codon after 210 amino acids and is predicted to result in nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) of the corresponding mRNA (Figure 1). The second variant, c.791+1G>A, identified in patient 3857, affected the donor splice site of intron 8. No RNA was available for further analysis; however, the disruption of the donor splice site of intron 8 is predicted to cause the skipping of exon 8 with a frameshift and the gain of a stop codon in exon 9. By direct sequencing, we found the same variant in her affected brother, confirming the segregation of the variant with the disease. The third variant, a frameshift alteration in exon 4, c.352dupC, predicted to cause NMD, was found in the sporadic patient from family 467 and in her unaffected father; moreover, the wild-type allele was lost in three of the four tumors analyzed. The fourth variant, a frameshift alteration in exon 14, c.1602delA, was confirmed in a patient from family 307 and his unaffected father, but not in his affected brother (Figure 1). The lack of segregation of the c.1602delA variant in one of the affected, and its presence in the healthy father, might argue against its pathogenic role; however, the mutated LZTR1 allele was retained in the two available tumors of II:2 (Figure 1). To rule out the possibility of non-paternity and to determine which paternal chromosome 22 was inherited by the two siblings, we performed microsatellite analysis in the family. The six microsatellites tested (D22S420, D22S1174, D22S1154, D22S1163, D22S277 and D22S1170) ruled out non-paternity and clearly demonstrated that the siblings inherited the two different chromosomes from the father. In addition, the microsatellite analysis of the brothers' tumors demonstrated that in both cases the paternal chromosome was retained in the tumors (Figure 1).

Table 1. Germline LZTR1 variants in schwannomatosis families.

| LZTR1a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | Sample | Inheritance | Affected | Variant | Effect |

| 3701 | De novo | Yes | c.212A>G | p.(His71Arg) | |

| 422 | I:2 | No | c.243T>G | p.(Tyr81*) | |

| II:1 | De novo | Yes | c.243T>G | p.(Tyr81*) | |

| 467b | I:1 | No | c.352dupC | p.(Arg118Profs*28) | |

| II:1 | De novo | Yes | c.352dupC | p.(Arg118Profs*28) | |

| 318 | De novo | Yes | c.373_375delGTC | p.(Val125del) | |

| 302 | De novo | Yes | c.513delG | p.(Leu171Phefs*29) | |

| 268 | De novo | Yes | c.555_556dupCA | p.(Lys186Thrfs*15) | |

| 244 | De novo | Yes | c.560T>G | p.(Leu187Arg) | |

| 288 | De novo | Yes | c.628C>T | p.(Arg210*) | |

| 3857b | II:1 | Familial | Yes | c.791+1G>A | r.spl? |

| II:2 | Familial | Yes | c.791+1G>A | r.spl? | |

| 388 | De novo | Yes | c.850C>T | p.(Arg284Cys) | |

| 325 | De novo | Yes | c.1018C>T | p.(Arg340*) | |

| 476 | De novo | Yes | c.1199T>G | p.(Met400Arg) | |

| 176b | I:1 | De novo | Yes | c.1373dupG | p.(His459Profs*210) |

| II:1 | Familial | Yes | c.1373dupG | p.(His459Profs*210) | |

| 183 | De novo | Yes | c.1394C>A | p.(Ala465Glu) | |

| 389 | De novo | Yes | c.1486delG | p.(Ala496Profs*60) | |

| 307b | I:1 | No | c.1602delA | p.(Lys534Asnfs*22) | |

| II:1 | Familial | Yes | Wild type | ||

| II:2 | Familial | Yes | c.1602delA | p.(Lys534Asnfs*22) | |

| 174 | De novo | Yes | c.1779delA | p.(Gln593Hisfs*7) | |

| 148 | I:1 | No | c.1807delG | p.(Val603*) | |

| II:1 | De novo | Yes | c.1807delG | p.(Val603*) | |

| 504 | De novo | Yes | c.2089C>T | p.(Arg697Trp) | |

| 408 | I:1 | No | c.2278T>C | p.(Cys760Arg) | |

| II:1 | De novo | Yes | c.2278T>C | p.(Cys760Arg) | |

| 259 | De novo | Yes | c.2284C>T | p.(Gln762*) | |

| 381 | De novo | Yes | c.2487dupA | p.(Asp830Argfs*21) | |

Reference LZTR1 sequence: NM_006767.3. Nucleotide numbering starts with the A of the ATG translation initiation codon as +1.

Variants identified by exome sequencing.

Figure 1.

Sequence analysis of LZTR1 in blood and tumors of mutated patients. Asterisks indicate subjects in the family who carry the variant. (a) The frameshift variant in exon 13 of LZTR1 was detected in the genomic DNA from the proband (arrow) and his affected father. The variant was present in the proband's schwannoma T714, which retained both alleles. (b) The frameshift variant in exon 16 of LZTR1 is present in the proband and her unaffected father and is retained in two schwannomas. (c) A frameshift variant in exon 14, c.1602delA (p.Lys534Asnfs*22), was identified in the proband from family 307 and his unaffected father, but not in the affected brother. The altered LZTR1 allele was retained in two tumors of the brother. Haplotype analysis for chromosome 22 markers in the family clearly indicated that the affected siblings inherited the two different chromosomes 22 from their father.

To further assess the involvement of LZTR1 in schwannomatosis, we screened all coding sequence and exon/intron boundaries of LZTR1 in 60 additional SMARCB1-unrelated schwannomatosis cases. Previously unidentified deleterious variants in LZTR1 were found in 18 of these cases. In total, 22 distinct LZTR1 variants (Table 1) were identified in 24 of 74 subjects from 70 unrelated families (30% and 43% of sporadic and familial cases, respectively). In five sporadic cases, for which parental DNA was available, the LZTR1 variant was inherited from an unaffected parent.

The LZTR1 variants found were nonsense or frameshift predicted to cause NMD in nine patients. In one patient (381), we found a frameshift variant that led to a new stop codon in the 3′-untranslated open reading frame, predicting an elongated protein. In patient 318 we identified an in-frame deletion of three nucleotides, predicted to cause deletion of valine 124 in the LZTR1 protein, which would disrupt the Kelch domain. Seven different missense variants were found in LZTR1; they involve amino acids highly conserved across species (Supplementary Table 3) and predicted to be deleterious by MutationTaster,20 PolyPhen 2 (ref. 18) and SIFT.19 Four of these missense variants involve amino acids (His71, Leu187, Arg284 and Met400) likely to disrupt the Kelch domain; the missense variants involving Ala465, Arg697 and Cys760 are likely to disrupt the first, the second and the last BTB domains, respectively.

To evaluate the presence of mosaicism in patients without LZTR1 variants, we sequenced LZTR1 in five tumors from three unrelated cases, but all were wild type.

We then checked loss on 22q by microsatellite and MLPA analyses (Supplementary Figure 1). LOH/MLPA analyses showed losses of 22q involving the LZTR1 locus in 14 of 28 tumors from 11 unrelated patients. D22S420 was not informative in tumors from four patients; in each of these cases, sequencing analysis showed that the mutant LZTR1 allele was retained in the tumors with reduction of the wild-type peak height, suggesting loss of the wild-type allele. In Supplementary Table 4, we summarize the somatic NF2 variants in schwannomatosis-associated schwannomas from patients with germinal LZTR1 variants.

Finally, we tested LZTR1 protein immunostaining in 22 tumors from nine unrelated patients with or without LZTR1 deleterious variants (Supplementary Figure 2). We used seven vestibular schwannomas from seven unrelated NF2 patients as positive controls. Compared with NF2-associated schwannomas, tumors from patients with variants in LZTR1 exhibited absent or reduced immunostaining. In contrast, tumors from LZTR1-unrelated schwannomatosis patients showed diffuse positive immunostaining, comparable with the NF2-associated tumors. Tumors from patients with nonsense or frameshift LZTR1 variants had almost complete negative immunostaining, whereas patients carrying splicing or missense variants showed reduced immunostaining compared with the NF2-associated schwannomas.

Discussion

Currently, germline deleterious variants in two tumor suppressor genes, SMARCB1 and LZTR1, are involved in schwannomatosis predisposition.5,10 In our study, we report our experience with LZTR1 gene mutational screening in a large cohort of SMARCB1-negative schwannomatosis patients. We found 24 patients, from 22 unrelated families, carrying germline variants of LZTR1. Unlike glioblastomas, where somatic variants are preferentially located in the Kelch domains of the LZTR1 protein,24 our data confirm that, in schwannomatosis patients, germline LZTR1 variants occur along the entire sequence of the gene. However, we identified LZTR1 variants in a lower proportion of patients compared with the earlier report:10 43% versus 100% and 30% versus 73% of familial and sporadic patients, respectively. One explanation might be our mutation-detection strategy, as we used HRMA to screen the entire coding sequence of the gene instead of direct sequencing; however, HRMA has an overall sensitivity of 99.3% to detect heterozygous variants25 and, in our experience, it is more sensitive than direct sequencing in detecting NF2 mosaic alterations.26 Another explanation might be the patient selection criteria. Piotrowski et al10 only included patients with a molecularly confirmed diagnosis of schwannomatosis by the finding of different NF2 variants in multiple tumors of the patients. In contrast, we analyzed patients with a confirmed clinical diagnosis according to the current schwannomatosis diagnostic criteria,4 and we performed molecular diagnosis on multiple schwannomas only in 15 patients (1 familial and 14 sporadic). If we focus on the 14 sporadic patients with a confirmed diagnosis of tumors, we found variants in 10 of them (71%), a result comparable to that of the previous report.10 Our lower detection rate in the entire cohort of our patients may be because some might actually be mosaic NF2, and, consequently, the diagnostic criteria for schwannomatosis should be reevaluated in the light of these new discoveries.

Our work confirms that LZTR1 is the most prevalent gene causing schwannomatosis. However, a fraction of schwannomatosis cases, mainly the sporadic ones, remain genetically unsolved. For these unexplained cases we cannot exclude the presence of unrecognized large deletions or duplications of the LZTR1 gene that are not detected by Sanger sequencing; however, genomic rearrangements are usually rarer than point variants. To explain the LZTR1- and SMARCB1-negative patients, Piotrowski et al10 hypothesized the presence of somatic mosaicism for SMARCB1 or LZTR1 variants. However, we demonstrated the absence of mosaicism in at least three SMARCB1- and LZTR1-negative patients by the analysis of multiple tumors of the patients, which did not carry alterations in SMARCB1 or LZTR1 but showed different somatic NF2 variants. Furthermore, multiple tumors from two of these patients showed positive LZTR1 immunostaining, suggesting the lack of involvement of LZTR1 in schwannoma development. Considering that we did not find SMARCB1 or LZTR1 deleterious variants in six familial schwannomatosis patients analyzed, our findings suggest the involvement of an as yet unidentified schwannomatosis gene(s) in a subset of cases.

The mutational analysis of LZTR1 in sporadic schwannomatosis patients reveals some inconsistences. First, variants were inherited from an unaffected parent in nine sporadic patients (from this and Piotrowski et al10 reports) and there were no additional affected members in their families. Incomplete penetrance might be one explanation, but the lack of families with multiple affected members prevents the verification of this hypothesis.

In addition, we found a family (307) with two affected siblings; only one of them carried the LZTR1 deleterious variant that was inherited by the unaffected father, whereas the other sibling had wild-type LZTR1 and SMARCB1 sequences; furthermore, the two affected brothers inherited two different chromosomes 22 from the father. This suggests that more than one gene could be involved in the same schwannomatosis family.

Currently, there is no evidence regarding protein interactions between LZTR1 and SMARCB1, nor that they are part of a common signaling pathway. LZTR1 encodes a member of the BTB-kelch superfamily; the protein localizes exclusively to the Golgi network where it may help stabilize the Golgi complex.27 Recent studies also suggest that LZTR1 is an adaptor in CUL3 ubiquitin ligase complexes.24 The tumor suppressor SMARCB1 is a core component of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex;28 the complex is involved in nucleosome mobilization and makes compacted DNA accessible to transcription factors and repair enzymes. In the future, schwannomatosis research will be focused on understanding how proteins with so dissimilar functions could cause the same disorder.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that molecular analysis of the LZTR1 gene in clinical genetics practice may contribute to molecular characterization of schwannomatosis patients, especially in distinguishing schwannomatosis with mosaic NF2. However, the role of LZTR1 in the pathogenesis of schwannomatosis needs to be further clarified. In addition, the assessment of genomic DNA from LZTR1- and SMARCB1-negative schwannomatosis patients and their tumors should also be carried out to discover other genes contributing to the pathogenesis of this disorder.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from Istituto Toscano Tumori and Children's Tumor Foundation (to LP). We thank Traci Toy for her technical assistance with sequencing, Bret Harry for computational server maintenance and Benedicte Chareyre for her contribution at the beginning of the project. Computational resources were provided by the UCLA DNA Microarray Facility. VC was supported by the K12 Child Health Research Career Development Award (2K12HD034610-16), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences UCLA CTSI Grant UL1TR000124, Pediatric Cancer Research Foundation and the Miranda D. Beck Pediatric Cancer Research Foundation. Finally, we would like to thank all the patients/families for their kind collaboration.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

Supplementary Material

References

- Huang JH, Simon SL, Nagpal S, Nelson PT, Zager EL. Management of patients with schwannomatosis: report of six cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2004;62:353–361. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2003.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby LB, Jones D, Davis K, et al. Molecular analysis of the NF2 tumor-suppressor gene in schwannomatosis. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:1293–1302. doi: 10.1086/301633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCollin M, Woodfin W, Kronn D, Short MP. Schwannomatosis: a clinical and pathologic study. Neurology. 1996;46:1072–1079. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.4.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin SR, Blakeley JO, Evans DG, et al. Update from the 2011 International Schwannomatosis Workshop: From genetics to diagnostic criteria. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A:405–416. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsebos TJ, Plomp AS, Wolterman RA, Robanus-Maandag EC, Baas F, Wesseling P. Germline mutation of INI1/SMARCB1 in familial schwannomatosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:805–810. doi: 10.1086/513207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd C, Smith MJ, Kluwe L, Balogh A, Maccollin M, Plotkin SR. Alterations in the SMARCB1 (INI1) tumor suppressor gene in familial schwannomatosis. Clin Genet. 2008;74:358–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield KD, Newman WG, Bowers NL, et al. Molecular characterisation of SMARCB1 and NF2 in familial and sporadic schwannomatosis. J Med Genet. 2008;4:332–339. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.056499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau G, Noguchi T, Bourdon V, Sobol H, Olschwang S. SMARCB1/INI1 germline mutations contribute to 10% of sporadic schwannomatosis. BMC Neurol. 2011;11:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-11-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith MJ, Wallace AJ, Bowers NL, et al. Frequency of SMARCB1 mutations in familial and sporadic schwannomatosis. Neurogenetics. 2012;13:141–145. doi: 10.1007/s10048-012-0319-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski A, Xie J, Liu YF, et al. Germline loss-of-function mutations in LZTR1 predispose to an inherited disorder of multiple schwannomas. Nat Genet. 2014;46:182–187. doi: 10.1038/ng.2855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sestini R, Bacci C, Provenzano A, Genuardi M, Papi L. Evidence of a four-hit mechanism involving SMARCB1 and NF2 in schwannomatosis-associated schwannomas. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:227–231. doi: 10.1002/humu.20679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43:491–498. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yourshaw M, Taylor P, Rao AR, Martín MG, Nelson SF.Rich annotation of DNA sequencing variants by leveraging the ensembl variant effect predictor with plugins Brief Bioinform 2014. e-pub ahead of print 12 March 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Desmet FO, Hamroun D, Lalande M, Collod-Béroud G, Claustres M, Béroud C. Human Splicing Finder: an online bioinformatics tool to predict splicing signals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:e67. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese MG, Eeckman FH, Kulp D, Haussler D. Improved Splice Site Detection in Genie. J Comp Biol. 1997;4:311–323. doi: 10.1089/cmb.1997.4.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucaki EJ, Shirley BC, Rogan PK. Prediction of mutant mRNA splice isoforms by information theory-based exon definition. Hum Mutat. 2013;34:557–565. doi: 10.1002/humu.22277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng PC, Henikoff S. SIFT: Predicting amino acid changes that affect protein function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3812–3814. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz JM, Rödelsperger C, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:575–576. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0810-575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goujon M, McWilliam H, Li W, et al. A new bioinformatics analysis tools framework at EMBL-EBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W695–W699. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliam H, Li W, Uludag M, et al. Analysis Tool Web Services from the EMBL-EBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W597–W600. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frattini V, Trifonov V, Chan JM, et al. The integrated landscape of driver genomic alterations in glioblastoma. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1141–1149. doi: 10.1038/ng.2734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittwer CT. High-resolution DNA melting analysis: advancements and limitations. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:857–859. doi: 10.1002/humu.20951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sestini R, Provenzano A, Bacci C, Orlando C, Genuardi M, Papi L. NF2 mutation screening by denaturing high-performance liquid chromatography and high-resolution melting analysis. Genet Test. 2008;12:311–318. doi: 10.1089/gte.2007.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nacak TG, Leptien K, Fellner D, Augustin HG, Kroll J. The BTB-kelch protein LZTR-1 is a novel Golgi protein that is degraded upon induction of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5065–5071. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509073200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euskirchen G, Auerbach RK, Snyder M. SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling factors: multiscale analyses and diverse functions. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:30897–30905. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.309302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.