Abstract

Cilia regulate several developmental and homeostatic pathways that are critical to survival. Sensory cilia of photoreceptors regulate phototransduction cascade for visual processing. Mutations in the ciliary protein RPGR (retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator) are a prominent cause of severe blindness disorders due to degeneration of mature photoreceptors. However, precise function of RPGR is still unclear. Here we studied the involvement of RPGR in ciliary trafficking by analyzing the composition of photoreceptor sensory cilia (PSC) in Rpgrko retina. Using tandem mass spectrometry analysis followed by immunoblotting, we detected few alterations in levels of proteins involved in proteasomal function and vesicular trafficking in Rpgrko PSC, prior to onset of degeneration. We also found alterations in the levels of high molecular weight soluble proteins in Rpgrko PSC. Our data indicate RPGR regulates entry or retention of soluble proteins in photoreceptor cilia but spares the trafficking of key structural and phototransduction-associated proteins. Given a frequent occurrence of RPGR mutations in severe photoreceptor degeneration due to ciliary disorders, our results provide insights into pathways resulting in altered mature cilia function in ciliopathies.

Cilia are microtubule-based antenna-like extensions of the plasma membrane in nearly all cell types, which regulate diverse developmental and homeostatic functions, including specification of left-right asymmetry, cardiac development, renal function and neurosensation1,2. Cilia formation is initiated when the mother centriole (also called basal body) docks at the apical plasma membrane and nucleates the assembly and extension of microtubules in the form of axoneme. Distal to the basal body, cilia possess a gate-like structure called the transition zone (TZ), which is thought to act as a barrier for allowing selective protein cargo to enter the axoneme microtubules by a conserved process called intraflagellar transport3,4,5. Defects in cilia formation or function result in severe ciliopathies, ranging from developmental disorders, including mental retardation, disruption of left-right asymmetry and skeletal defects to degenerative diseases, such as renal cystic diseases and retinal degeneration due to photoreceptor dysfunction6,7.

Photoreceptors develop unique sensory cilia in the form of light-sensing outer segment (OS). The OS, in addition to the ciliary membrane, consists of membranous discs loaded with photopigment rhodopsin and other proteins such as peripherin/rds and rod outer membrane protein ROM18,9. The region between the basal body and the distal cilium is called TZ or connecting cilium of photoreceptors 8,9,10. Defects in TZ structure and function result in altered trafficking of proteins to the OS, leading to photoreceptor degenerative diseases, such as Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP)11.

RP is a genetically and clinically heterogeneous progressive hereditary disorder of the retina12. X-linked forms of RP (XLRP) are among the most severe forms and account for 10–20% of inherited retinal dystrophies. XLRP is characterized by photoreceptor degeneration, with night blindness during the first or second decade, generally followed by significant vision loss by fourth decade13. Mutations in the ciliary protein retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR) account for >70% of XLRP cases and 15–20% of simplex RP cases14,15,16,17,18,19,20. RPGR mutations are also reported in patients with atrophic macular degeneration, sensorineural hearing loss, respiratory tract infections, and primary cilia dyskinesia19,20,21,22,23,24.

RPGR localizes predominantly to the TZ of photoreceptor and other cilia25,26 and interacts with TZ-associated ciliary disease proteins26,27,28,29,30,31. Studies using animal models indicate that Rpgr ablation or mutation results in delayed yet severe retinal degeneration32,33,34,35. However, the precise function of RPGR and the mechanism of associated photoreceptor degeneration are poorly understood. In this report, we sought to assess the role of RPGR in ciliary trafficking by testing the effect of loss of RPGR on the composition of the photoreceptor sensory cilia in mice. Our results suggest that RPGR participates in maintaining the function of mature cilia by selectively regulating (directly or indirectly) trafficking of proteins involved in distinct yet overlapping pathways.

Results

Purification of photoreceptor sensory cilium (PSC)

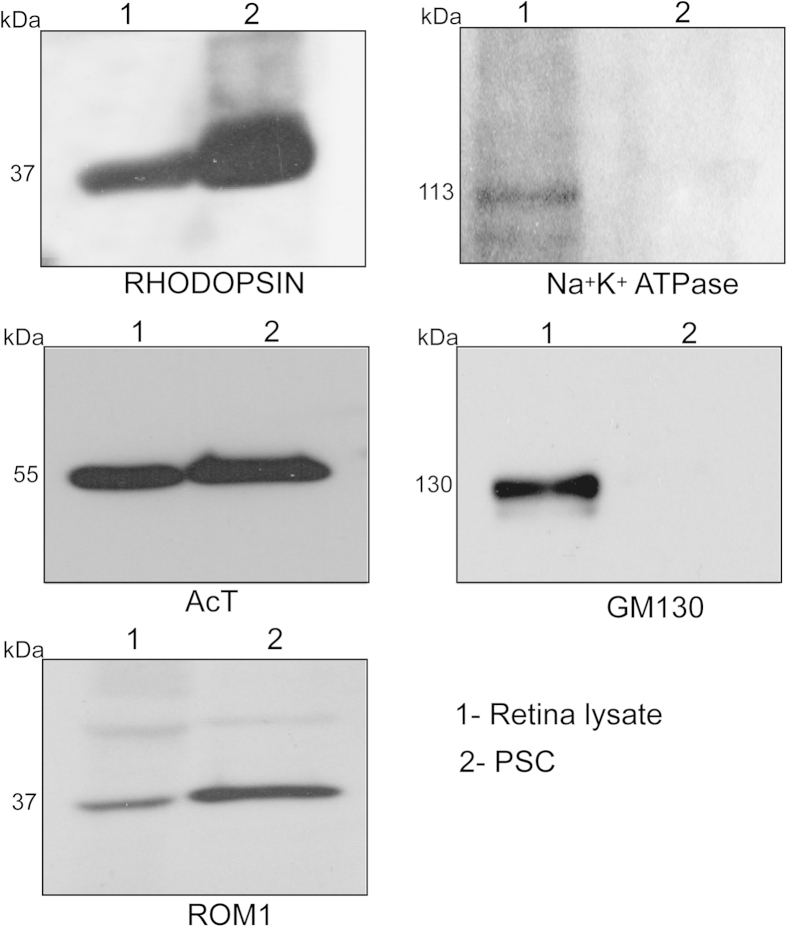

We and others previously showed that the Rpgrko mice exhibit photoreceptor degeneration starting at around 6 months of age32,35. Based on this information, we selected two stages of Rpgrko mice to assess PSC composition: 2 months and 4 months. We hypothesized that (i) these stages would represent changes in protein trafficking prior to onset of degeneration and (ii) progression in the changes observed from 2 to 4 months of age are likely candidates for true disease-associated defects. We used age-matched wild-type littermates as controls. The retinas were isolated and subjected to sub cellular fractionation as described in the Methods section. Fluorescence microscopic analysis of our PSC preparations using anti-rhodopsin and ciliary marker ARL13B (ADP-ribosylation Factor like 13B) showed that the fractions were relatively pure sensory cilia (Fig. 1). To further validate the purity of the PSC fractions, we carried out immunoblot analysis using antibodies against marker proteins residing in cytosol (inner segment), mitochondria, as well as in the cilia. As shown in Fig. 2, PSC fraction was enriched in sensory cilia proteins rhodopsin, acetylated α-tubulin and rod outer membrane (ROM1) protein but not in inner segment localized proteins GM130 (Golgi marker) and Na+K+ATPase (a mitochondrial marker).

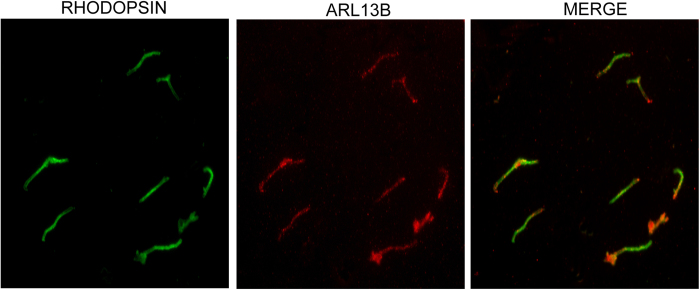

Figure 1. Immunofluorescence analysis of isolated PSC:

PSC was isolated from mouse retina and stained with anti-rhodopsin (green) and anti-ARL13B (red) antibodies. Merge shown co-localization of rhodopsin with the ciliary marker.

Figure 2. Purity of the PSC:

PSC fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using indicated antibodies. Lane 1: total retina lysate; Lane 2: PSC. Molecular weight markers are shown in kilo Daltons (kDa). Enrichment of known ciliary proteins was detected whereas cytosolic proteins were undetectable in the PSC.

Proteomic analysis of PSC

To test the role of RPGR in regulating protein trafficking into the cilia, we assessed the composition of the PSC of the Rpgrko mice as compared to wild type mice. We performed MS/MS analysis of the PSC at 2 months and 4 months of age (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 online, respectively). Each experiment consisted of 6 retinas from wild type and 6 retinas from Rpgrko mice. Data are average of three biological replicates at each age. At 2 months of age, we detected 1366 proteins in wild type and Rpgrko PSC. At 4 months, we detected a total of 1614 proteins in wild type and Rpgrko PSC. As predicted, RPGR was not detected in the Rpgrko PSC.

We then analyzed our MS/MS data to identify proteins that were increased or decreased in the in the Rpgrko PSC as compared to wild type and categorize them based on their relative abundance. To this end, we applied the following criteria: (i) the average emPAI values had to be <0.5 fold if the abundance of the protein decreased and >2 fold if abundance increased and (ii) the number of unique peptides had to be greater than 3, if a protein is not detected in the other genotype. Based on these criteria, the proteins that increased or decreased are listed in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4. At 2 months of age, we detected 28 proteins that decreased in amount by less than 0.5 fold in Rpgrko PSC as compared to wild type. On the other hand, we detected 30 proteins at 4 months of age that showed less than 0.5-fold reduction in Rpgrko PSC. Among the category of proteins whose relative abundance increased by >2-fold in Rpgrko PSC at 2 months of age, we detected 17 proteins, whereas at 4 months of age, we found 24 proteins in Rpgrko PSC.

Table 1. Proteins with reduced abundance in PSC of Rpgr ko at 2 months. S1, S2, and S3 are the three biological repeat samples used in the present study.

| emPAI VALUES | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identified Proteins | Accession Number | Molecular Weight | Fold Change | C57 Mean S1 S2 S3 | RpgrkoMean S1 S2 S3 |

| N-myc downstream-regulated gene 1 | NDRG1_MOUSE | 43 kDa | 0.2 | 0.343- 0.312, 0.411, 0.306 | 0.076-0.073, 0.059, 0.0966 |

| Protein Tfg | Q9Z1A1_MOUSE | 43 kDa | 0.2 | 0.343- 0.276, 0.355, 0.398 | 0.076- 0.071, 0.053, 0.1048 |

| SEC14like protein 2 | S14L2_MOUSE | 46 kDa | 0.2 | 0.316- 0.358, 0.275, 0.315 | 0.071- 0.069, 0.084, 0.06 |

| 26S proteasome nonATPase regulatory subunit 3 | PSMD3_MOUSE | 61 kDa | 0.2 | 0.234- 0.256, 0.145, 0.301 | 0.0539- 0.0566, 0.038, 0.066 |

| EH domain containing protein 4 | EHD4_MOUSE | 61 kDa | 0.2 | 0.23- 0.18, 0.36, 0.15 | 0.053-0.051, 0.0399, 0.0686 |

| Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase | E9PYI8_MOUSE | 52 kDa | 0.3 | 0.44- 0.32, 0.56, 0.44 | 0.129-0.097, 0.250, 0.04 |

| Golgi reassembly stacking protein 2, isoform CRA_c | A2ATI6_MOUSE | 37 kDa | 0.3 | 0.291- 0.213, 0.442, 0.218 | 0.0889-0.0811, 0.0690, 0.1166 |

| Insulin degrading enzyme | F6RPJ9_MOUSE | 114 kDa | 0.3 | 0.288- 0.251, 0.290, 0.323 | 0.088- 0.079, 0.080, 0.105 |

| Septin2 | SEPT2_MOUSE | 42 kDa | 0.3 | 0.257- 0.222, 0.321, 0.228 | 0.0793- 0.072, 0.063, 0.1022 |

| Bardet-Biedl syndrome 4 protein homolog | BBS4_MOUSE | 58 kDa | 0.4 | 0.315- 0.306, 0.467, 0.172 | 0.116- 0.107, 0.120, 0.121 |

| Isoform 2 of Transmembrane emp24 domain-containing protein 10 | TMEDA_MOUSE | 11 kDa | 0.4 | 1.88- 1.89, 1.54, 2.21 | 0.698- 0.666, 0.723, 0.705 |

| Cullin3 | CUL3_MOUSE | 89 kDa | 0.4 | 0.287- 0.267, 0.345, 0.249 | 0.114- 0.108, 0.114, 0.12 |

| Farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase | FPPS_MOUSE | 41 kDa | 0.4 | 0.598- 0.549, 0.668, 0.577 | 0.264- 0.237, 0.212, 0.343 |

| 26S protease regulatory subunit 10B | PRS10_MOUSE | 44 kDa | 0.4 | 0.538- 0.556, 0.413, 0.645 | 0.24- 0.18, 0.27, 0.27 |

| T-complex protein 1 subunit zeta | TCPZ_MOUSE | 58 kDa | 0.4 | 1.04- 1.02, 1.06, 1.04 | 0.469- 0.447, 0.525, 0.435 |

| GTP-binding nuclear protein Ran | RAN_MOUSE | 24 kDa | 0.5 | 1.45- 1.33, 1.59, 1.43 | 0.667- 0.612, 0.734, 0.655 |

| Proliferation-associated protein 2G4 | PA2G4_MOUSE | 44 kDa | 0.5 | 0.337- 0.333, 0.411, 0.267 | 0.156- 0.149, 0.155, 0.164 |

| ATP-binding cassette subfamily F member 1 | ABCF1_MOUSE | 95 kDa | 0.5 | 0.31- 0.29, 0.3, 0.34 | 0.145- 0.116, 0.178, 0.141 |

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(T) subunit gammaT1 | GBG1_MOUSE | 9 kDa | 0.5 | 14.5- 13.8, 14.2, 15.5 | 6.8- 5.3, 6.9, 8.2 |

| Prom1 protein | Q8R056_MOUSE | 94 kDa | 0.5 | 1.04- 1.03, 1.01, 1.08 | 0.502- 0.489, 0.623, 0.394 |

| Glutathione S transferase P 1 | GSTP1_MOUSE | 24 kDa | 0.5 | 1.87- 1.77, 1.82, 2.02 | 0.933- 0.899, 0.929, 0.971 |

| Coatomer subunit beta | COPB_MOUSE | 107 kDa | 0.5 | 0.391- 0.313, 0.405, 0.455 | 0.197- 0.177, 0.2, 0.214 |

| Isoform 2 of ADP ribosylation factor-like protein 6 | ARL6_MOUSE | 22 kDa | 0.5 | 2.61- 2.57, 2.16, 3.1 | 1.36- 1.22, 1.48, 1.38 |

| Isoform 3 of Glyoxalase domain containing protein 4 | GLOD4_MOUSE | 31 kDa | 0.5 | 0.667- 0.606, 0.689, 0.706 | 0.359- 0.348, 0.377, 0.352 |

| Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(I)/G(S)/G(T) subunit beta1 | GBB1_MOUSE | 37 kDa | 0.5 | 30.9- 31.4, 30.2, 31.1 | 16.7- 15.9, 16.3, 17.9 |

| Exportin2 | XPO2_MOUSE | 110 kDa | 0.5 | 0.418- 0.402, 0.471, 0.381 | 0.226- 0.197, 0.228, 0.253 |

| Cullin5 | CUL5_MOUSE | 91 kDa | 0.5 | 0.28- 0.23, 0.3, 0.31 | 0.151- 0.146, 0.162, 0.145 |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 1 | PSMD1_MOUSE | 106 kDa | 0.5 | 0.237- 0.241, 0.209, 0.261 | 0.129- 0.116, 0.131, 0.14 |

Table 2. Proteins with reduced abundance in PSC of Rpgr ko at 4 months. S1, S2, and S3 are the three biological repeat samples used in the present study.

| emPAI VALUES | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identified Proteins | Accession Number | Molecular Weight | Fold Change | C57Mean S1 S2 S3 | RpgrkoMean S1 S2 S3 |

| Fascin2 | FSCN2_MOUSE | 55 kDa | 0 | 0.403- 0.409, 0.41, 0.39 | 0 |

| Vesicle trafficking protein SEC22a | SC22A_MOUSE | 35 kDa | 0 | 0.307- 0.298, 0.311, 0.312 | 0 |

| Insulin degrading enzyme | IDE_MOUSE | 118 kDa | 0.1 | 0.48- 0.46, 0.59, 0.39 | 0.0556- 0.0601, 0.0567, 0.05 |

| Oral facial digital syndrome 1 protein homolog | OFD1_MOUSE | 117 kDa | 0.1 | 0.412- 0.409, 0.410, 0.417 | 0.0565- 0.0557, 0.0578, .056 |

| Cullin5 | CUL5_MOUSE | 91 kDa | 0.2 | 0.452- 0.448, 0.465, 0.443 | 0.109- 0.112, 0.098, 0.117 |

| GTP-binding protein 1 | GTPB1_MOUSE | 72 kDa | 0.3 | 0.531- 0.54, 0.529, 0.524 | 0.138- 0.141, 0.137, 0.136 |

| Ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 O | UBE2O_MOUSE | 141 kDa | 0.3 | 0.227- 0.219, 0.236, 0.226 | 0.0701- 0.0698, 0.0709, 0.0696 |

| Prolactin inducible protein | PIP_HUMAN | 17 kDa | 0.3 | 1.25- 1.248, 1.252, 1.25 | 0.409- 0.4089, 0.412, 0.4061 |

| Jouberin | AHI1_MOUSE | 120 kDa | 0.3 | 0.335- 0.334, 0.336, 0.3349 | 0.111- 0.109, 0.112, 0.112 |

| Potassium voltage gated channel subfamily V member 2 | KCNV2_MOUSE | 64 kDa | 0.3 | 0.464- 0.467, 0.463, 0.462 | 0.156- 0.158, 0.157, 0.153 |

| Protein transport protein Sec24C | SC24C_HUMAN | 118 kDa | 0.3 | 0.406- 0.398, 0.411, 0.409 | 0.141- 0.140, 0.143, 0.14 |

| WD repeat-containing protein 35 | WDR35_MOUSE | 134 kDa | 0.4 | 0.355- 0.35, 0.3539, 0.3551 | 0.124- 0.125, 0.122, 0.125 |

| Vacuolar protein sorting associated protein 26B | VP26B_MOUSE | 39 kDa | 0.4 | 0.473- 0.471, 0.475, 0.473 | 0.169- 0.168, 0.170, 0.169 |

| SH3containing GRB2-like protein 3-interacting protein 1 | SGIP1_PSAOB | 88 kDa | 0.4 | 0.42- 0.419, 0.421, 0.42 | 0.152- 0.153, 0.1521, 0.1509 |

| Proliferation-associated protein 2G4 | PA2G4_MOUSE | 44 kDa | 0.4 | 0.611- 0.609, 0.612, 0.612 | 0.233- 0.234, 0.299, 0.166 |

| ATP-binding cassette subfamily F member 1 | ABCF1_MOUSE | 95 kDa | 0.4 | 0.433- 0.432, 0.435, 0.432 | 0.177- 0.179, 0.176, 0.176 |

| Coiled-coil and C2 domain containing protein 2A | C2D2A_MOUSE | 188 kDa | 0.4 | 0.714- 0.709, 0.711, 0.722 | 0.297- 0.298, 0.297, 0.296 |

| Nck-associated protein 1 | NCKP1_MOUSE | 129 kDa | 0.4 | 0.31- 0.309, 0.311, 0.313 | 0.13- 0.11, 0.134, 0.146 |

| F-actin capping protein subunit beta | CAPZB_MOUSE | 31 kDa | 0.4 | 0.739- 0.74, 0.7385, 0.7385 | 0.33- 0.329, 0.3401, 0.3209 |

| AP3 complex subunit mu2 | AP3M2_MOUSE | 47 kDa | 0.5 | 0.474- 0.472, 0.474, 0.4746 | 0.216- 0.215, 0.2161, 0.2169 |

| WD40 repeat-containing protein SMU1 | SMU1_MOUSE | 58 kDa | 0.5 | 0.25- 0.239, 0.259, 0.252 | 0.114- 0.113, 0.115, 0.114 |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 3 | PSMD3_MOUSE | 61 kDa | 0.5 | 0.233- 0.232, 0.234, 0.2321 | 0.108- 0.1079, 0.1085, 0.1076 |

| Glutathione S transferase P 1 | GSTP1_MOUSE | 24 kDa | 0.5 | 2.53- 2.529, 2.535, 2.526 | 1.18- 1.185, 1.178, 1.177 |

| TBC1 domain family member | TBC24_MOUSE | 63 kDa | 0.5 | 0.407- 0.411, 0.406, 0.4031 | 0.213- 0.211, 0.214, 0.214 |

| Voltage-dependent anion selective channel protein 1 | VDAC1_RAT | 31 kDa | 0.5 | 9.26- 9.248, 9.259, 9.273 | 4.88- 4.85, 4.91, 4.88 |

| WD repeat containing protein 7 | WDR7_MOUSE | 163 kDa | 0.5 | 0.56-0 .568, 0.557, 0.555 | 0.297- 0.299, 0.3, 0.292 |

| Cytoplasmic dynein 2 heavy chain 1 | DYHC2_MOUSE | 492 kDa | 0.5 | 0.769- 0.768, 0.774, 0.765 | 0.413- .4123, .3998, .4269 |

| Phosducin | PHOS_MOUSE | 28 kDa | 0.5 | 5.96- 5.971, 5.993, 5.916 | 3.2- 3.214, 3.189, 3.197 |

| Kinesin like protein KIF1A | KIF1A_MOUSE | 192 kDa | 0.5 | 0.429- .4289, .431, .4271 | 0.232- 0.2324, 0.2295, 0.2241 |

| UPF0568 protein C14orf166 homolog | CN166_MOUSE | 28 kDa | 0.5 | 0.68- 0.679, 0.686, 0.675 | 0.37- 0.365, 0.375, 0.37 |

Table 3. Proteins with increased abundance in PSC of Rpgr ko at 2 months. S1, S2, and S3 are the three biological repeat samples used in the present study.

| emPAI VALUES | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identified Proteins | Accession Number | Molecular Weight | Fold Change | C57Mean S1 S2 S3 | RpgrkoMean S1 S2 S3 |

| Ubiquitin thio-esterase OTUB1 | D3YWF6_MOUSE | 28 kDa | INF | 0 | 0.565- 0.521, 0.577, 0.597 |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 7 | PSMD7_MOUSE | 37 kDa | INF | 0 | 0.296- 0.278, 0.3, 0.31 |

| Isoform 5 of Dynamin1like protein | DNM1L_MOUSE | 24 kDa | 3.4 | 7.77- 7.31, 7.68, 8.32 | 26.7- 27.1, 25.7, 27.3 |

| Isoform 1 of Gammaadducin | ADDG_MOUSE | 75 kDa | 3 | 0.136- 0.145, 0.131, 0.132 | 0.404- 0.399, 0.413, 0.4 |

| Potassium/sodium hyperpolarization activated cyclic nucleotide gated channel 1 | HCN1_MOUSE | 102 kDa | 2.9 | 0.0986- 0.0924, 0.0999, 0.1035 | 0.285- 0.263, 0.278, 0.314 |

| WD repeat containing protein 1 | WDR1_MOUSE | 66 kDa | 2.6 | 0.212- 0.195, 0.225, 0.216 | 0.542- 0.431, 0.558, 0.637 |

| Isoform 2 of Disks large homolog 1 | DLG1_MOUSE | 100 kDa | 2.5 | 0.101- 0.099, 0.115, 0.089 | 0.253- 0.229, 0.261, 0.269 |

| Isoform 2 of Putative tyrosine protein phosphatase auxilin | AUXI_MOUSE | 99 kDa | 2.5 | 0.103- 0.089, 0.110, 0.11 | 0.256- 0.247, 0.273,0.248 |

| Thioredoxin related transmembrane protein 2 | D3Z2J6_MOUSE | 30 kDa | 2.4 | 0.376- 0.352, 0.4, 0.376 | 0.892- 0.886, 0.879, 0.911 |

| Ras-related protein Rab2A | RAB2A_MOUSE | 24 kDa | 2.4 | 0.939- 0.894, 1, 0.923 | 2.29- 2.16, 2.88, 1.83 |

| Serine/threonine protein phosphatase 2A 56 kDa regulatory subunit epsilon isoform | 2A5E_MOUSE | 55 kDa | 2.3 | 0.337- 0.265, 0.351, 0.395 | 0.789- 0.667, 0.8, 0.9 |

| Isoform 2 of Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 5 | CSPG5_MOUSE | 57 kDa | 2.2 | 0.182- 0.166, 0.190, 0.19 | 0.396- 0.382, 0.4, 0.406 |

| Annexin A6 | ANXA6_MOUSE | 76 kDa | 2.1 | 0.59- 0.46, 0.62, 0.69 | 1.23- 1.20, 1.37, 1.12 |

| Isoform 3 of Neuronal cell adhesion molecule | NRCAM_MOUSE | 139 kDa | 2.1 | 0.0969- 0.0917, 0.099, 0.1 | 0.203- 0.210, 0.179, 0.22 |

| Isoform 3 of Cell adhesion molecule 2 | CADM2_MOUSE | 44 kDa | 2.1 | 0.665- 0.659, 0.7, 0.636 | 1.4- 1.09, 1.6, 1.51 |

| Vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 | B0QZN5_MOUSE | 18 kDa | 2 | 2.34- 2.19, 2.86, 1.97 | 4.6- 3.9, 4.8, 5.1 |

| Septin7 | E9Q1G8_MOUSE | 51 kDa | 2 | 0.552- 0.592, 0.488, 0.576 | 1.12- 1.08, 1.2, 1.08 |

Table 4. Proteins with increased abundance in PSC of Rpgr ko at 4 months. S1, S2, and S3 are the three biological repeat samples used in the present study.

| emPAI VALUES | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identified Proteins | Accession Number | Molecular Weight | Fold Change | C57Mean S1 S2 S3 | RpgrkoMean S1 S2 S3 |

| Collectrin | TMM27_MOUSE | 25 kDa | INF | 0 | 1.32- 1.28, 1.31, 1.37 |

| Ermin | ERMIN_MOUSE | 32 kDa | INF | 0 | 0.979- 0.989, 0.982, 0.966 |

| Ras GTPase activating like protein IQGAP2 | IQGA2_MOUSE | 181 kDa | 8.2 | 0.116- 0.115, 0.120, 0.113 | 0.945- 0.95, 0.943, 0.942 |

| Ras GTPase activating like protein IQGAP1 | IQGA1_MOUSE | 189 kDa | 5.7 | 0.0731- 0.0729, 0.073, 0.0732 | 0.415- 0.413, 0.445, 0.387 |

| Sarcolemmal membrane associated protein | SLMAP_MOUSE | 97 kDa | 5 | 0.258- 0.2581, 0.259, 0.2569 | 1.29- 1.285, 1.295, 1.29 |

| Na(+)/H(+) exchange regulatory cofactor NHERF1 | NHRF1_MOUSE | 39 kDa | 3 | 0.383- 0.381, 0.3829, 0.3851 | 1.14- 1.13, 1.15, 1.14 |

| Integrin alpha M | ITAM_MOUSE | 127 kDa | 3 | 0.223- 0.221, 0.224, 0.224 | 0.676- 0.675, 0.679, 0.674 |

| Integrin alpha V | ITAV_MOUSE | 115 kDa | 3 | 0.491- 0.5, 0.490, 0.483 | 1.5- 1.48, 1.51, 1.51 |

| Secretory carrier associated membrane protein 3 | SCAM3_MOUSE | 38 kDa | 2.9 | 0.278- 0.279, 0.2789, 0.2761 | 0.793- 0.791, 0.794, 0.794 |

| Beta-soluble NSF attachment protein | SNAB_MOUSE | 34 kDa | 2.8 | 0.974- .975, .9768, .9702 | 2.69- 2.7, 2.689, 2.681 |

| Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 | CSPG4_MOUSE | 252 kDa | 2.8 | 0.38- 0.37, 0.395, 0.375 | 1.05- 1.1, 1.04, 1.01 |

| Radixin | RADI_BOVIN | 69 kDa | 2.7 | 1.41- 1.399, 1.415, 1.416 | 3.74- 3.76, 3.749, 3.711 |

| Podocalyxin | PODXL_MOUSE | 53 kDa | 2.7 | 0.266- .265, .2657, .2673 | 0.716- 0.7149, 0.717, 0.7161, |

| Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 5 | CSPG5_MOUSE | 60 kDa | 2.6 | 0.497-0.498, 0.495, 0.498 | 1.31- 1.3, 1.299, 1.331 |

| Proteasome subunit alpha type1 | PSA1_MOUSE | 30 kDa | 2.5 | 0.366- 0.365, 0.368, 0.365 | 0.909- 0.911, 0.908, 0.908 |

| Sphingomyelin phosphodiesterase 2 | NSMA_MOUSE | 47 kDa | 2.5 | 0.321- 0.322, 0.323, 0.319 | 0.799- 0.798, 0.7989, 0.8001 |

| Gamma-soluble NSF attachment protein | SNAG_MOUSE | 35 kDa | 2.4 | 0.428- 0.427, 0.429, 0.428 | 1.04- 1.038, 1.041, 1.041 |

| Tectonin beta-propeller repeat containing protein 1 | TCPR1_MOUSE | 130 kDa | 2.2 | 0.162- 0.163, 0.161, 0.162 | 0.351- 0.3509, 0.3512, 0.3509 |

| Alpha-soluble NSF attachment protein | SNAA_MOUSE | 33 kDa | 2.2 | 1.47- 1.465, 1.478, 1.467 | 3.2- 3.11, 3.25, 3.24 |

| Myoferlin | MYOF_MOUSE | 233 kDa | 2.1 | 0.135- 0.136, 0.134, 0.1349, | 0.282- 0.2781, 0.28201, 0.2878 |

| PlexinB2 | PLXB2_MOUSE | 206 kDa | 2.1 | 0.243- 0.2425, 0.244, 0.2425 | 0.511- 0.51, 0.513, 0.51 |

| Vacuolar protein sorting-associated protein 35 | VPS35_MOUSE | 92 kDa | 2 | 0.154- 0.155, 0.1529, 0.1541 | 0.303- 0.3, 0.299, 0.31 |

| Ras-related protein Rab14 | RAB14_HUMAN | 24 kDa | 2 | 1.22- 1.219, 1.24, 1.201 | 2.43- 2.41, 2.45, 2.43 |

| CAAX prenyl protease 1 homolog | FACE1_MOUSE | 55 kDa | 2 | 0.259- 0.257, 0.261, 0.259 | 0.53- 0.519, 0.538, 0.533 |

It is becoming clear that the TZ also acts as a size-exclusion barrier for soluble proteins36,37,38. Interestingly, soluble proteins that reduced in abundance by 0.5-fold in Rpgrko PSC decreased from 13 out of 28 at 2 months of age (46%; average molecular weight: 51.7 kDa) to 6 out of 30 at 4 months of age (20%; average molecular weight of 80 kDa) (Table 5). Whereas 2 out of 17 proteins that increased in amount at 2 months of age (11.7%; average molecular weight of 99.5 kDa) are soluble proteins, 7 out of 24 proteins increased in amount at 4 months of age (~30%; average molecular weight of 99 kDa) are soluble proteins (Table 5). We therefore, suggest that the barrier for entry or retention of soluble proteins into the PSC is affected in the absence of RPGR.

Table 5. Soluble proteins with altered in abundance in Rpgr ko PSC. No predicted post-translational modifications to allow membrane association were detected in these proteins. MW: predicted molecular weight; kDa: kilo Daltons.

| 2 months | 4 months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decreased | Increased | Decreased | Increased | ||||

| Name | MW (kDa) | Name | MW (kDa) | Name | MW (kDa) | Name | MW (kDa) |

| NDRG1 | 43 | DLG1 | 100 | IDE | 118 | IQGAP1 | 189 |

| S14L2 | 46 | AUX1 | 99 | ABCF1 | 95 | IQGAP2 | 181 |

| PSMD3 | 61 | CC2D2A | 188 | SLMAP | 97 | ||

| EHD4 | 61 | GSTP1 | 24 | SNAB | 34 | ||

| E9PYI8 | 52 | PHOS | 28 | SNAG | 35 | ||

| A2ATI6 | 37 | CN166 | 28 | SNAA | 33 | ||

| F6RPJ9 | 114 | TCPR1 | 130 | ||||

| BBS4 | 58 | AVERAGE | 80 | AVERAGE | 99.8 | ||

| FPPS | 41 | ||||||

| ABCF1 | 95 | ||||||

| GBG1 | 9 | ||||||

| GSTP1 | 24 | ||||||

| GLOD4 | 31 | ||||||

| AVERAGE | 51.7 | AVERAGE | 99.5 | ||||

Phototransduction proteins and known ciliopathy-associated proteins in Rpgr ko PSC

Previous studies showed a reduction in photoreceptor function in the Rpgrko mice32. We therefore, tested if this phenotype was due to an earlier defect in reduced translocation of selected phototransduction proteins to the OS. Our MS/MS analysis as well as validation by immunoblotting revealed no significant difference in the amount of arrestin, ROM1, and cyclic nucleotide gated channel CNGB1 in the Rpgrko PSC as compared to wild type mice. These results suggest that photoreceptor dysfunction in the absence of RPGR in mice is not likely due to a defect in the trafficking of the tested phototransduction-associated proteins.

Alterations in BBS-associated proteins are associated with photoreceptor dysfunction among other ciliopathy disorders. Our analysis revealed BBS1, BBS2, BBS5, and BBS7 in the PSC; however, their levels did not alter between age-matched wild type and Rpgrko PSC. Similarly, we did not detect differences in IFT polypeptides or associated Kinesin motor subunits in the Rpgrko PSC.

Proteins with altered abundance in Rpgr ko PSC

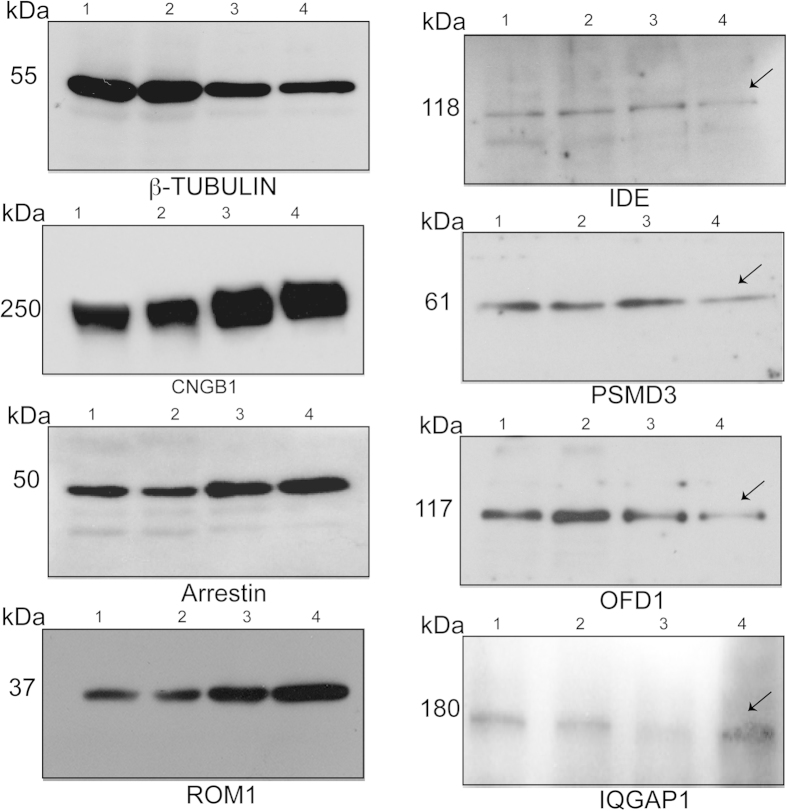

A majority of proteins that decreased in amount in Rpgrko PSC at both stages belonged to the category of ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and cilia function (Tables 1 and 2 and Supplementary Figure S1). As the UPS is enriched at the cilium and has been detected in the PSC in earlier proteomics analyses (discussed later)10,39, we selected PSMD3 (26 S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 3) and Insulin degrading enzyme (IDE) for further analysis. Immunoblot analysis of PSC from wild type and Rpgrko showed a reduction in the amount of both PSMD3 and IDE1 in the Rpgrko PSC (Fig. 3). Total amount of these proteins did not alter, indicating that there was no change in the expression levels of PSMD3 and IDE in Rpgrko retina. It was recently shown that proteasomal function is modulated by ciliary-centrosomal protein OFD139. As we detected reduced abundance of OFD1 in the Rpgrko PSC at 4 months of age, we performed immunoblot analysis using anti-OFD1 antibody. Our results validated the MS/MS data and showed reduced amount of OFD1 amount in Rpgrko PSC (Fig. 3). No change in the total protein levels of OFD1 was detected in these analyses.

Figure 3. Validation of selected proteins identified by MS/MS analysis.

PSC from wild type (WT) and Rpgrko mouse retina were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting using indicated antibodies. Lanes 1 and 2: total retina lysate from WT and Rpgrko mice, respectively; Lanes 3 and 4: PSC from WT and Rpgrko mice, respectively. Arrows indicate altered proteins in the Rpgrko PSC. Molecular weight markers are shown in kilo Daltons (kDa).

We found high representation of the category of membrane trafficking and intracellular transport among the proteins that were increased in Rpgrko PSC (Tables 3 and 4 and Supplementary Figure S2). Specifically, we detected more than 5-fold increase in IQ-domain GTPase Activating Proteins IQGAP1, which is predicted to be involved in intracellular trafficking and neuronal regulation40. Given a crucial role of small GTPases and their regulation in the maintenance of PSC28,41,42, we validated the levels of IQGAP1 by immunoblot analysis. We found that indeed, amount of IQGAP1 is increased in the Rpgrko PSC relative to the wild type (Fig. 3). No change in the total levels of IQGAP1 was detected.

Localization of altered proteins in the retina

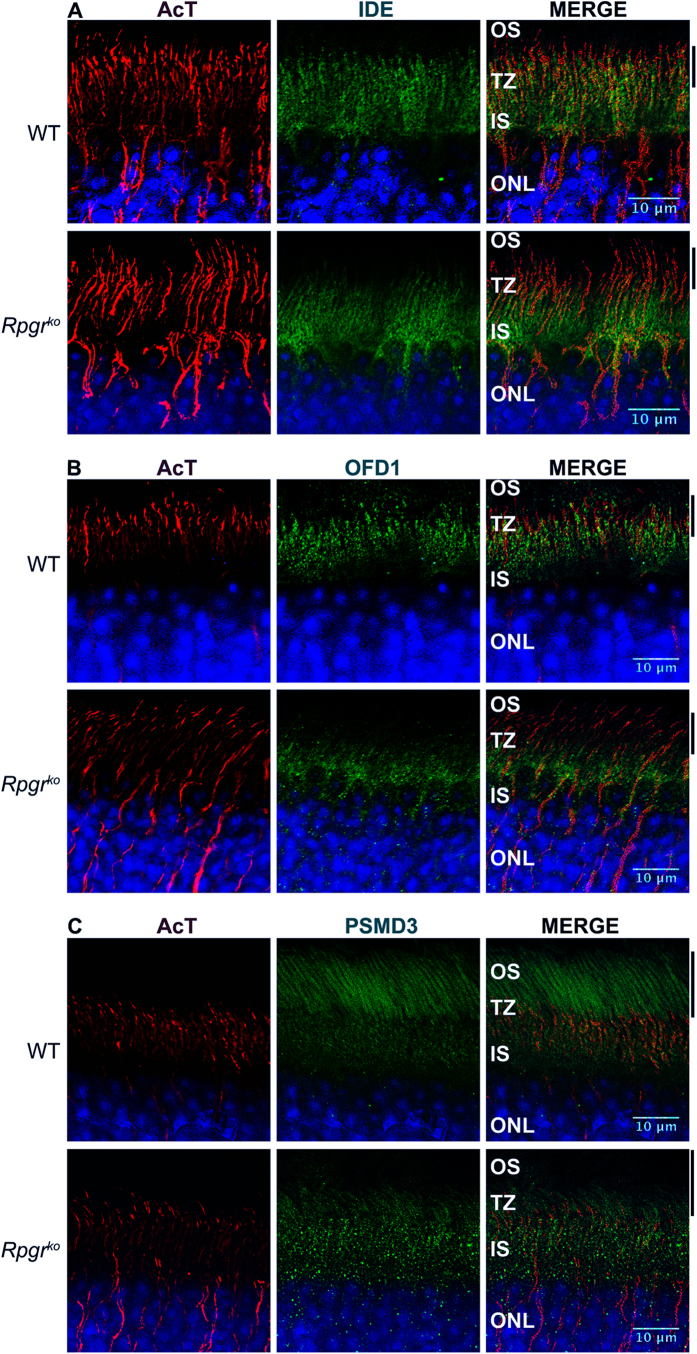

Although all the proteins identified in our dataset have been previously reported as part of the mouse PSC proteome10, the localization of IDE, PSMD3, OFD1 and IQGAP1 has not been examined in mammalian retina. To corroborate our findings, we performed immunofluorescence analysis of these proteins using adult mouse retina. Our analysis revealed that in addition to the inner segment (IS) and outer plexiform layer (OPL), IDE, PSMD3, OFD1, and IQGAP1 localize to the TZ, as determined by co-staining with ciliary markers acetylated α-tubulin (AcT) or detyrosinated tubulin (DeTyr) (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Figure S3). Interestingly, PSMD3 was also detected in the OS. Consistent with a prominent role of OFD1 at the basal body, OFD1 co-localizes with γ-tubulin in photoreceptor IS (Supplementary Figure S3).

Figure 4. Localization of PSC proteins in mouse retina.

Wild type (WT) and Rpgrko retinal sections were stained with indicated antibodies. Nuclei (blue) are stained with Hoechst. OS: outer segment; TZ: transition zone; IS: inner segment; ONL: outer nuclear layer; AcT: acetylated α-tubulin. Scale bar: 10 μm. Solid lines indicate the area that is stained by the respective antibody (green) in WT but not in Rpgrko retina.

We next examined the effect of loss of RPGR on the localization of these proteins. Immunofluorescence analysis of age-matched Rpgrko mouse retinas revealed interesting observations (Fig. 4). We found reduced IDE and OFD1 associated signal reduced in the TZ with a concomitant mislocalization in the IS and outer nuclear layer (ONL) of Rpgrko retina (Fig. 4A,B). PSMD3 staining revealed strikingly reduced staining in the OS and increased in TZ/IS of Rpgrko retina (Fig. 4C).

Discussion

Although RPGR is widely expressed and regulates ciliary trafficking, it is puzzling that RPGR mutations in humans do not result in typical cilia-associated systemic and developmental or early-onset defects. Rather, RPGR mutations are one of the most common causes of severe photoreceptor degenerative diseases of adulthood19,43. Photoreceptor cilia are unique with respect to their demands of maintenance of ciliary function. They undergo periodic shedding of distal tips of cilia with concomitant renewal of membrane and proteins at the base. It is estimated that about 10% of the OS tips are shed each day44,45. This is accompanied by massive transport of opsin and other OS proteins to the cilium46,47. Hence, it is conceivable that maintenance of ciliary function plays a crucial role in photoreceptor health. Our findings suggest that RPGR is one such regulator of functional maintenance of mature photoreceptors. RPGR accomplishes this task by likely modulating the docking and trafficking of key proteins involved in proteasomal function and intracellular protein trafficking.

Selecting 2 and 4 months of age of Rpgrko mice provided a unique opportunity to ascertain defects in photoreceptor protein trafficking that are likely to cause photoreceptor degeneration rather than a secondary effect of degeneration. Earlier studies using immunofluorescence analyses had revealed mistrafficking of opsins in Rpgrko retina at 6 months of age32. Our results indicate that loss of RPGR may not directly affect trafficking of opsin or other phototransduction proteins and the mislocalization of opsin observed in the Rpgrko retina could have been an effect of degenerating photoreceptors. Support of this hypothesis comes from several previous studies showing opsin mislocalization as a common phenotype across multiple gene mutations associated with retinal degeneration due to photoreceptor dysfunction48.

Membrane proteins targeted to cilia may dock at the periciliary membrane and then are loaded onto axonemal cargo carriers for delivery to the OS via the TZ38. However, fate of soluble proteins is not completely understood. It was reported that small soluble molecules such as GFP could equilibrate between inner and outer segments in frog photoreceptors49. Moreover, it was shown that arrestin and transducin diffuse through the TZ50,51,52. These findings suggest an absence of a diffusion barrier in photoreceptors, at least for smaller proteins. We detected a specific alteration in the levels of soluble proteins in the Rpgrko PSC. We found an overall increase in higher molecular weight soluble proteins at 4 months of age as compared to 2 months. As ciliary base is considered analogous to the nuclear pore complex and the role of another retinal ciliopathy protein RP2 in maintaining the function of nuclear pore proteins at the base of cilia53,54, it is conceivable that there is a size-exclusion barrier of soluble proteins at the TZ of photoreceptors. This barrier is likely maintained by RPGR and its interacting proteins. Additional analyses of the effect of RPGR and its multiprotein complexes on the integrity of such a barrier should provide crucial insights into the precise role of TZ of cilia.

Our data point to an important role of UPS in the pathogenesis of RPGR-associated photoreceptor degeneration. In addition to identifying several UPS components that show varying levels in Rpgrko PSC as compared to wild type, validation of three proteins that are directly or indirectly involved in UPS provide further support to the association of the UPS in cilia-dependent XLRP pathogenesis. We provide four scenarios to support this hypothesis: (i) among the UPS components identified in our PSC proteome, PSMD3 showed reduced levels at both 2 and 4 months of age in the Rpgrko PSC. A previous report on the involvement of another PSMD subunit PSMD13 in modulating RPE65 levels to regulate retinal health further supports the role of PSMD proteins in retinal health55. Moreover, UPS dysfunction has been reported in several retinal degenerative diseases56. The UPS is concentrated at the PSC and is implicated in regulating levels of phototransduction and other PSC proteins to cope with immense oxidative stress in photoreceptors10. Decrease in PSMD3 levels indicates that Rpgrko photoreceptors have reduced ability to cope with oxidative stress that accumulates over time; (ii) the UPS regulates insulin signal transduction by modulating degradation of key components, such as insulin receptor substrates57. Insulin, in turn, can inhibit proteasome and this action is dependent upon IDE58, which is also reduced in the Rpgrko PSC; (iii) PSMD3 modulates insulin resistance in association with polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs)59, which are a key component of photoreceptor OS membranes60,61,62; (iv) OFD1, which is also reduced in Rpgrko PSC, is shown to modulate proteasome function39. Given that an intronic mutation in OFD1 is associated with XLRP63, we reckon that RPGR and OFD1 play overlapping roles in the manifestation of XLRP pathogenesis. Validation of these hypotheses warrants further investigations.

Vesicular trafficking by small GTPases in photoreceptors is critical for their function and survival28,41. Our analyses revealed abundant quantities of small GTPase regulators, such as IQGAP1 in the PSC of Rpgrko mice. IQGAPs are not only involved in intracellular trafficking, they are also implicated in actin-microtubule interaction and regulation of cytoskeletal dynamics. Commensurate with this, our analysis revealed alterations in levels of proteins belonging to the families of cytoskeleton-based vesicular trafficking to cilia. These results corroborate previous findings that RPGR regulates protein trafficking likely by modulating the activity of GTPases or regulators of GTPase activity28.

It should be noted that there is not much overlap between proteins whose abundance changes between 2 and 4 months. We posit that the proteins that show increased abundance at 2 months in the PSC may not be as abundant at 4 months due to progression of disease condition and associated subtle variations that may affect their abundance in the PSC in Rpgrko mice. Hence, such proteins would not make the cutoff of the threshold in our analysis. On the other hand, proteins that show reduced abundance at 2 months but are no longer detected at 4 months may reflect reduction in overall expression levels of such proteins. This would reduce to such an extent even in a wild type mouse retina that the variations are no longer significant in Rpgrko are and hence, do not make the cut off in our analyses.

Regulators of protein trafficking, such as RPGR are involved in maintaining the structure and function of mature cilia. Such functions are specifically crucial in mature neurons, which are under immense oxidative stress. Defects in RPGR result in subtle but incremental insult, which result in neurodegeneration. Our studies thus, provide clues to understanding pathways involved in the maintenance of mature cilia, which will also assist in delineating the pathogenesis of retinal degeneration in systemic ciliopathies.

Methods

Mice

Rpgrko mice (in C57BL6/J background) were procured from Dr. Tiansen Li (National Eye Institute) and were characterized earlier32. Control C57BL6/J mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Both strains of mice were reared in the same animal facility at UMASS Medical School. All methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. All experimental protocols were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Institutional Biosafety Committee of UMASS Medical School.

Antibodies

We procured antibodies against IDE and PSMD3 from Genetex (Irvine, CA); rhodopsin and IQGAP1, from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA) and; anti-OFD1, anti-detyrosinated tubulin and anti-GM130 from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Anti-acetylated α-tubulin and γ-tubulin were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO); anti-ARL13B was obtained from Proteintech (Chicago, IL) and; Na+K+ ATPase was obtained from Santa Cruz (Dallas, TX). Anti-ROM1 antibody, anti-cone arrestin and anti-CNGB1 were gifts of Dr. Muna I. Naash (University of Oklahoma), Dr. Cheryl M. Craft (University of Southern California), and Dr. Martin Biel (Center for Drug Research, Institute of Pharmacology, Germany), respectively.

PSC preparation

Mouse PSC was prepared essentially as described10,64. Briefly, fresh mouse eyes were dissected and retinas were placed in a tube with 150 μl of 8% OptiPrep (Nycomed, Oslo, Norway) prepared in Ringer’s buffer (130 mM NaCl, 3.6 mM KCl, 2.4 mM MgCl2, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, containing 0.02 mM EDTA) and vortexed for 1 min. The samples were centrifuged at 200 × g for 1 min, and the supernatant containing the PSC was transferred to fresh eppendorf tube. The resultant pellet was dissolved in 150 μl of 8% OptiPrep, vortexed, and centrifuged again at 200 × g for 1 min. These steps were repeated five times. The PSC was pooled (∼2 ml), overlaid on a 10–30% continuous gradient of OptiPrep in Ringer’s buffer, and centrifuged for 50 min at 26,500 × g. PSC were collected from second band (about two-thirds of the way from the top), diluted three times with Ringer’s buffer, and centrifuged for 3 min at 500 × g to remove the cell nuclei. The supernatant containing PSC was transferred to a new tube and centrifuged for 30 min at 26,500 × g. The pelleted material contained pure intact PSC.

Immunofluorescence and Immunoblotting

For staining of the isolated PSC complex preparations, 10 μl of the suspension was spotted on glass slides and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 15 minutes. Mouse retina was processed for immunofluorescence as described26,65,66. For staining with anti-PSMD3 and anti-IDE antibodies, consistent results were obtained when retinas were processed using paraffin-embedding65,66. Slides containing PSC and mouse retinal sections were washed with PBS, permeabilized, and blocked for 1 hour with blocking solution containing 5% normal goat serum with 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS in a humidifying chamber at RT. Primary antibodies were added and slides were incubated overnight at 4 °C. After washing three times with PBS, samples were incubated for 1 hour with goat anti-rabbit (or mouse) Alexa Fluor 488 nm or 546 nm secondary antibody at room temperature. Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies Corp.) was diluted with PBS to final 1 μg/mL and used to label the nuclei. Samples were washed with deionized water and then mounted (Fluoromount; Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) under glass coverslips and visualized using a microscope (Leica TCS SP5 II laser; Leica Microsystems).

For Immunoblotting, equal amount of protein samples (50 μg) were denatured at 95ºC for 5 min in 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 20% sucrose, 4% β-mercaptoethanol and separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Proteins were transferred onto Immobilon-FL membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Blots were blocked in 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) for 30 min and labeled with the primary antibody in 5% nonfat milk prepared in TBST for overnight. The blots were washed with TBST and labeled with a secondary anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to HRP and processed for chemiluminescence reaction.

Proteomic Analysis

Analyses of three biological replicates were performed using 6 retinas each from wild type and Rpgrko mice (total 18 retinas from each genotype). Samples were run ~1.5 cm into the resolving gel of 10% minigels (BioRad, Hercules, CA) and protein-containing regions were excised, destained, and cut into 1 × 1 mm pieces. Gel pieces were then placed in 1.5-ml eppendorf tubes with 1 ml of water for 30 min. The water was removed and 100μl of 250 mM ammonium bicarbonate was added. For reduction 20 μl of a 45 mM solution of 1, 4 dithiothreitol (DTT) was added and the samples were incubated at 50 C for 30 min. The samples were cooled to room temperature and alkylated by adding 20 μl of a 100 mM iodoacetamide solution for 30 min. Gel slices were washed twice with 1 ml water aliquots. The water was removed and 1 ml of 50:50 (50 mM Ammonium Bicarbonate: Acetonitrile) was placed in each tube and samples were incubated at room temperature for 1 hr. The solution was then removed and 200 μl of acetonitrile was added to each tube at which point the gels slices turned opaque white. The acetonitrile was removed and gel slices were further dried in a Speed Vac. Gel slices were rehydrated in 50 μl of 2 ng/μl trypsin (Sigma) in 0.01% ProteaseMAX Surfactant (Promega): 50 mM Ammonium Bicarbonate. Additional bicarbonate buffer was added to ensure complete submersion of the gel slices. Samples were incubated at 37oC for 21hrs. The supernatant of each sample was then removed and placed in a separate 1.5 ml eppendorf tube. Gel slices were further dehydrated with 100 μl of 80:20 (Acetonitrile: 1% formic acid). The extract was combined with the supernatants of each sample. The samples were then dried down in a Speed Vac. Samples were dissolved in 25 μl of 5% Acetonitrile in 0.1% trifluroacetic acid prior to injection on LC/MS/MS.

LC/MS/MS on Q Exactive

A 3 μl aliquot was directly injected onto a custom packed 2 cm x 100 μm C18 Magic 5 μ particle trap column. Peptides were then eluted and sprayed from a custom packed emitter (75 μm x 25 cm C18 Magic 3 μm particle) with a linear gradient from 95% solvent A (0.1% formic acid in water) to 35% solvent B (0.1% formic acid in Acetonitrile) in 90 minutes at a flow rate of 300 nl per minute on a Waters Nano Acquity UPLC system. Data dependent acquisitions were performed on a Q Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) according to an experiment where full MS scans from 300–1750 m/z were acquired at a resolution of 70,000 followed by 12 MS/MS scans acquired under HCD fragmentation at a resolution of 35,000 with an isolation width of 1.2 Da.

Data Analysis

Raw data files were processed with Proteome Discoverer (version 1.3) prior to searching with Mascot Server (version 2.4) against the Uniprot_Mouse database. Search parameters utilized were fully tryptic with 2 missed cleavages, parent mass tolerances of 10 ppm and fragment mass tolerances of 0.05 Da. A fixed modification of carbamidomethyl cysteine and variable modifications of acetyl (protein N-term), pyro glutamic for N-term glutamine, and oxidation of methionine were considered. Search results were loaded into the Scaffold Viewer (Proteome Software, Inc.) for comparisons of sample results between wild type and Rpgrko PSC. Prior to additional analyses, major contaminants such as keratins, ribosomal and mitochondrial proteins were removed from our PSC proteome to increase the specificity of identified proteins.

We used previously reported stringency criteria to enrich specifically altered proteins. All MS/MS samples were analyzed using Mascot search engine (Matrix Science, London, UK; version 2.4.0). Mascot was set up to search the SwissProt_062613 database (selected for mice) with a fragment ion mass tolerance of 0.050 Da and a parent ion tolerance of 10.0 PPM. Scaffold (version Scaffold_4.3.4, Proteome Software Inc., Portland, OR) was used to validate MS/MS based peptide and protein identifications. Peptide identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 95.0% probability by the Peptide Prophet algorithm67,68 with Scaffold delta-mass correction. Protein identifications were accepted if they could be established at greater than 95.0% probability and contained at least 3 identified peptides. We put false discovery rate (FDR) cutoff ~<1, which means that more than 99% of the proteins in our list were true proteins.

Quantitative proteomic analysis

Spectral counting has been used for differentiating the abundance of protein amount in complex mixture of different biological samples. However protein quantification by spectral counting would be biased by length of proteins because larger proteins generate more spectral counts as compared to smaller proteins. For our quantitative proteomic analysis, we adopted a previously described method called exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI)69. emPAI is widely used method in quantitative comparative proteomics and offers approximate, label-free, relative quantitation of the proteins in a mixture based on protein coverage by the peptide matches in a database search result. PAI (protein abundance index) of each protein was calculated by dividing number of observed peptides to the number of observable peptides per protein.

|

where Nobsd and Nobsbl are the number of unique observed peptides and the number of unique observable peptides per protein, respectively.

For absolute quantitation, PAI was converted to exponentially modified PAI (emPAI),

|

which is proportional to protein content in a protein mixture. Solubility prediction of identified proteins was calculated using Expropriator (http://mips.helmholtz-muenchen.de/proso/proso.seam)70.

Functional Analysis

After finding proteins, which are differently expressed, we performed pathway analysis by using DAVID (Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery) classification system. We analyzed differential expression of proteins based on >2 fold change, for both down regulated and up regulated, from overall wild type and knockout datasets.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Rao, K. N. et al. Ablation of retinal ciliopathy protein RPGR results in altered photoreceptor ciliary composition. Sci. Rep. 5, 11137; doi: 10.1038/srep11137 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (RO1-EY022372), Foundation Fighting Blindness and University of Massachusetts Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences (UMCCTS). We thank Dr. John Leszyk, Director of UMMS Proteomics Core facility for mass spectrometry.

Footnotes

Author Contributions K.N.R., L.L. and M.A.: performed experiments. H.K.: conceived the study and wrote the paper

References

- Oh E. C., Vasanth S. & Katsanis N. Metabolic Regulation and Energy Homeostasis through the Primary Cilium. Cell metabolism, 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.11.019 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singla V. & Reiter J. F. The primary cilium as the cell’s antenna: signaling at a sensory organelle. Science 313, 629–633 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czarnecki P. G. & Shah J. V. The ciliary transition zone: from morphology and molecules to medicine. Trends Cell Biol 22, 201–210, 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.02.001 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozminski K. G., Johnson K. A., Forscher P. & Rosenbaum J. L. A motility in the eukaryotic flagellum unrelated to flagellar beating. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90, 5519–5523 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum J. L. & Witman G. B. Intraflagellar transport. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 3, 813–825 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badano J. L., Mitsuma N., Beales P. L. & Katsanis N. The ciliopathies: an emerging class of human genetic disorders. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet 7, 125–148 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt F., Benzing T. & Katsanis N. Ciliopathies. The New England journal of medicine 364, 1533–1543, 10.1056/NEJMra1010172 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T. et al. The effect of peripherin/rds haploinsufficiency on rod and cone photoreceptors. JNeurosci 17, 8118–8128 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insinna C. & Besharse J. C. Intraflagellar transport and the sensory outer segment of vertebrate photoreceptors. Dev Dyn 237, 1982–1992 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q. et al. The proteome of the mouse photoreceptor sensory cilium complex. Mol Cell Proteom 6, 1299–1317 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand M. & Khanna H. Ciliary transition zone (TZ) proteins RPGR and CEP290: role in photoreceptor cilia and degenerative diseases. Exp Opin Ther Tar 16, 541–551, 10.1517/14728222.2012.680956 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckenlively J. R., Yoser S. L., Friedman L. H. & Oversier J. J. Clinical findings and common symptoms in retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Ophthalmol 105, 504–511 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman G. A., Farber M. D. & Derlacki D. J. X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Profile of clinical findings. Arch Ophthalmol 106, 369–375 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meindl A. et al. A gene (RPGR) with homology to the RCC1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor is mutated in X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (RP3). Nat Genet 13, 35–42 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roepman R. et al. Positional cloning of the gene for X-linked retinitis pigmentosa 3: homology with the guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor RCC1. Hum Mol Gen 5, 1035–1041 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breuer D. K. et al. A comprehensive mutation analysis of RP2 and RPGR in a North American cohort of families with X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Am J Hum Genet 70, 1545–1554 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharon D. et al. X-linked retinitis pigmentosa: mutation spectrum of the RPGR and RP2 genes and correlation with visual function. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 41, 2712–2721 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu X. et al. RPGR mutation analysis and disease: an update. Hum Mutat 28, 322–328 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan L. S. et al. Prevalence of mutations in eyeGENE probands with a diagnosis of autosomal dominant retinitis pigmentosa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54, 6255–6261, 10.1167/iovs.13-12605 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan L. S. & Daiger S. P. Inherited retinal degeneration: exceptional genetic and clinical heterogeneity. Mol Med Today 2, 380–386 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannaccone A. et al. Clinical and immunohistochemical evidence for an X linked retinitis pigmentosa syndrome with recurrent infections and hearing loss in association with an RPGR mutation. J Med Genet 40, e118 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenekoop R. K. et al. Novel RPGR mutations with distinct retinitis pigmentosa phenotypes in French-Canadian families. Am J Ophthalmol 136, 678–687 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore A. et al. RPGR is mutated in patients with a complex X linked phenotype combining primary ciliary dyskinesia and retinitis pigmentosa. J Med Genet 43, 326–333 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyagari R. et al. X-linked recessive atrophic macular degeneration from RPGR mutation. Genomics 80, 166–171 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong D. H. et al. RPGR isoforms in photoreceptor connecting cilia and the transitional zone of motile cilia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 44, 2413–2421 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna H. et al. RPGR-ORF15, which is mutated in retinitis pigmentosa, associates with SMC1, SMC3, and microtubule transport proteins. J Biol Chem 280, 33580–33587 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murga-Zamalloa C., Swaroop A. & Khanna H. Multiprotein Complexes of Retinitis Pigmentosa GTPase Regulator (RPGR), a Ciliary Protein Mutated in X-Linked Retinitis Pigmentosa (XLRP). Adv Exp Med Biol 664, 105–114, 10.1007/978-1-4419-1399-9_13 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murga-Zamalloa C. A., Atkins S. J., Peranen J., Swaroop A. & Khanna H. Interaction of retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR) with RAB8A GTPase: implications for cilia dysfunction and photoreceptor degeneration. Hum Mol Genet 19, 3591–3598, 10.1093/hmg/ddq275 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roepman R. et al. The retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR) interacts with novel transport-like proteins in the outer segments of rod photoreceptors. Hum Mol Genet 9, 2095–2105 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu X. et al. RPGR ORF15 isoform co-localizes with RPGRIP1 at centrioles and basal bodies and interacts with nucleophosmin. Hum Mol Genet 14, 1183–1197 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. et al. The retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR)- interacting protein: subserving RPGR function and participating in disk morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100, 3965–3970 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong D. H. et al. A retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR)-deficient mouse model for X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (RP3). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97, 3649–3654 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitton K. P. et al. The leucine zipper of NRL interacts with the CRX homeodomain. A possible mechanism of transcriptional synergy in rhodopsin regulation. J Biol Chem 275, 29794–29799 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q. et al. Different RPGR exon ORF15 mutations in Canids provide insights into photoreceptor cell degeneration. Hum Mol Genet 11, 993–1003 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson D. A. et al. Rd9 is a naturally occurring mouse model of a common form of retinitis pigmentosa caused by mutations in RPGR-ORF15. PloS one 7, e35865, 10.1371/journal.pone.0035865 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awata J. et al. NPHP4 controls ciliary trafficking of membrane proteins and large soluble proteins at the transition zone. J Cell Sci 127, 4714–4727, 10.1242/jcs.155275 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craige B. et al. CEP290 tethers flagellar transition zone microtubules to the membrane and regulates flagellar protein content. J Cell Biol 190, 927–940, 10.1083/jcb.201006105 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachury M. V., Seeley E. S. & Jin H. Trafficking to the ciliary membrane: how to get across the periciliary diffusion barrier? Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 26, 59–87, 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113337 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. P. et al. Ciliopathy proteins regulate paracrine signaling by modulating proteasomal degradation of mediators. J Clin Invest, 10.1172/JCI71898 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White C. D., Erdemir H. H. & Sacks D. B. IQGAP1 and its binding proteins control diverse biological functions. Cell Signal 24, 826–834, 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.12.005 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deretic D. et al. rab8 in retinal photoreceptors may participate in rhodopsin transport and in rod outer segment disk morphogenesis. J Cell Sci 108 (Pt 1), 215–224 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin H. et al. The conserved Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins assemble a coat that traffics membrane proteins to cilia. Cell 141, 1208–1219, 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.015 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaroop A. What’s in a name? RPGR mutations redefine the genetic and phenotypic landscape in retinal degenerative diseases. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54, 1417, 10.1167/iovs.13-11750 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besharse J. C., Hollyfield J. G. & Rayborn M. E. Turnover of rod photoreceptor outer segments. II. Membrane addition and loss in relationship to light. J Cell Biol 75, 507–527 (1977). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVail M. M. Kinetics of rod outer segment renewal in the developing mouse retina. J Cell Biol 58, 650–661 (1973). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. & Deretic D. Molecular complexes that direct rhodopsin transport to primary cilia. Prog Ret Eye Res 38, 1–19, 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2013.08.004 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young R. W. Passage of newly formed protein through the connecting cilium of retina rods in the frog. J Ultrastruct Res 23, 462–473 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth T. J. & Gross A. K. Defective trafficking of rhodopsin and its role in retinal degenerations. Int Rev Cell Molecular Biol 293, 1–44, 10.1016/B978-0-12-394304-0.00006-3 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert P. D., Schiesser W. E. & Pugh E. N. Jr. Diffusion of a soluble protein, photoactivatable GFP, through a sensory cilium. J Gen Physiol 135, 173–196, 10.1085/jgp.200910322 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert P. D., Strissel K. J., Schiesser W. E., Pugh E. N. Jr. & Arshavsky V. Y. Light-driven translocation of signaling proteins in vertebrate photoreceptors. Trends Cell Biol 16, 560–568, 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.09.001 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair K. S. et al. Light-dependent redistribution of arrestin in vertebrate rods is an energy-independent process governed by protein-protein interactions. Neuron 46, 555–567 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slepak V. Z. & Hurley J. B. Mechanism of light-induced translocation of arrestin and transducin in photoreceptors: interaction-restricted diffusion. IUBMB life 60, 2–9, 10.1002/iub.7 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd T. W., Fan S. & Margolis B. L. Localization of retinitis pigmentosa 2 to cilia is regulated by Importin beta2. J Cell Sci 124, 718–726, 10.1242/jcs.070839 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishinger J. F. et al. Ciliary entry of the kinesin-2 motor KIF17 is regulated by importin-beta2 and RanGTP. Nat Cell Biol 12, 703–710, 10.1038/ncb2073 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. et al. Rescue of enzymatic function for disease-associated RPE65 proteins containing various missense mutations in non-active sites. J Biol Chem 289, 18943–18956, 10.1074/jbc.M114.552117 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobanova E. S., Finkelstein S., Skiba N. P. & Arshavsky V. Y. Proteasome overload is a common stress factor in multiple forms of inherited retinal degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110, 9986–9991, 10.1073/pnas.1305521110 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rome S., Meugnier E. & Vidal H. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is a new partner for the control of insulin signaling. Curr Opin Clin Nut Metab Care 7, 249–254 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett R. G., Fawcett J., Kruer M. C., Duckworth W. C. & Hamel F. G. Insulin inhibition of the proteasome is dependent on degradation of insulin by insulin-degrading enzyme. J Endocrinol 177, 399–405 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J. S. et al. Genetic variants at PSMD3 interact with dietary fat and carbohydrate to modulate insulin resistance. J Nut 143, 354–361, 10.3945/jn.112.168401 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agbaga M. P., Mandal M. N. & Anderson R. E. Retinal very long-chain PUFAs: new insights from studies on ELOVL4 protein. J Lipid Res 51, 1624–1642, 10.1194/jlr.R005025 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aveldano M. I. & Bazan N. G. Molecular species of phosphatidylcholine, -ethanolamine, -serine, and -inositol in microsomal and photoreceptor membranes of bovine retina. J Lipid Res 24, 620–627 (1983). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazelova J., Ransom N., Astuto-Gribble L., Wilson M. C. & Deretic D. Syntaxin 3 and SNAP-25 pairing, regulated by omega-3 docosahexaenoic acid, controls the delivery of rhodopsin for the biogenesis of cilia-derived sensory organelles, the rod outer segments. J Cell Sci 122, 2003–2013, 10.1242/jcs.039982 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb T. R. et al. Deep intronic mutation in OFD1, identified by targeted genomic next-generation sequencing, causes a severe form of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (RP23). Hum Mol Genet 21, 3647–3654, 10.1093/hmg/dds194 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda A. et al. Role of photoreceptor-specific retinol dehydrogenase in the retinoid cycle in vivo. J Biol Chem 280, 18822–18832, 10.1074/jbc.M501757200 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. et al. Ablation of the X-linked retinitis pigmentosa 2 (Rp2) gene in mice results in opsin mislocalization and photoreceptor degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54, 4503–4511, 10.1167/iovs.13-12140 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian B. A.M, Khan N. W. & Khanna H. Loss of Raf-1 kinase inhibitory protein delays early-onset severe retinal ciliopathy in Cep290rd16 mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 14, 5788–5794, 10.1167/iovs.14-14954 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller A., Nesvizhskii A. I., Kolker E. & Aebersold R. Empirical statistical model to estimate the accuracy of peptide identifications made by MS/MS and database search. Anal Chem 74, 5383–5392 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesvizhskii A. I., Keller A., Kolker E. & Aebersold R. A statistical model for identifying proteins by tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 75, 4646–4658 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihama Y. et al. Exponentially modified protein abundance index (emPAI) for estimation of absolute protein amount in proteomics by the number of sequenced peptides per protein. Mol Cell Proteomics : MCP 4, 1265–1272, 10.1074/mcp.M500061-MCP200 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smialowski P. et al. Protein solubility: sequence based prediction and experimental verification. Bioinformatics 23, 2536–2542, 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl623 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.