Abstract

Background

A variety of in‐service emergency care training courses are currently being promoted as a strategy to improve the quality of care provided to seriously ill newborns and children in low‐income countries. Most courses have been developed in high‐income countries. However, whether these courses improve the ability of health professionals to provide appropriate care in low‐income countries remains unclear. This is the first update of the original review.

Objectives

To assess the effects of in‐service emergency care training on health professionals' treatment of seriously ill newborns and children in low‐income countries.

Search methods

For this update, we searched the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, part of The Cochrane Library (www.cochranelibrary.com); MEDLINE, Ovid SP; EMBASE, Ovid SP; the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), part of The Cochrane Library (www.cochranelibrary.com) (including the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group Specialised Register); Science Citation Index and Social Sciences Citation Index, Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) Web of Knowledge/Science and eight other databases. We performed database searches in February 2015. We also searched clinical trial registries, websites of relevant organisations and reference lists of related reviews. We applied no date, language or publication status restrictions when conducting the searches.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials, non‐randomised trials, controlled before and after studies and interrupted‐time‐series studies that compared the effects of in‐service emergency care training versus usual care were eligible for inclusion. We included only hospital‐based studies and excluded community‐based studies. Two review authors independently screened and selected studies for inclusion.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted data and assessed study risk of bias and confidence in effect estimates (certainty of evidence) for each outcome using GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation). We described results and presented them in GRADE tables.

Main results

We identified no new studies in this update. Two randomised trials (which were included in the original review) met the review eligibility criteria. In the first trial, newborn resuscitation training compared with usual care improved provider performance of appropriate resuscitation (trained 66% vs usual care 27%, risk ratio 2.45, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.75 to 3.42; moderate certainty evidence) and reduced inappropriate resuscitation (trained mean 0.53 vs usual care 0.92, mean difference 0.40, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.66; moderate certainty evidence). Effect on neonatal mortality was inconclusive (trained 28% vs usual care 25%, risk ratio 0.77, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.48; N = 27 deaths; low certainty evidence). Findings from the second trial suggest that essential newborn care training compared with usual care probably slightly improves delivery room newborn care practices (assessment of breathing, preparedness for resuscitation) (moderate certainty evidence).

Authors' conclusions

In‐service neonatal emergency care courses probably improve health professionals' treatment of seriously ill babies in the short term. Further multi‐centre randomised trials evaluating the effects of in‐service emergency care training on long‐term outcomes (health professional practice and patient outcomes) are needed.

Plain language summary

In‐service training for health professionals to improve care of seriously ill newborns and children in low‐income countries

What question was the review asking?

This is the first update of the original Cochrane review, whose objective was to find out whether additional emergency care training programmes can improve the ability of health workers in poor countries to care for seriously ill newborns and children admitted to hospitals. Researchers at The Cochrane Collaboration searched for all studies that could answer this question and found two relevant studies.

What are the key messages?

The review authors suggest that giving health professionals in poor countries additional training in emergency care probably improves their ability to care for seriously ill newborns. We need additional high‐quality studies, including studies in which health professionals are trained to care for seriously ill older children.

Background: training health professionals to care for seriously ill babies and children

In poor countries, many babies and children with serious illnesses die even though they have been cared for in hospitals. One reason for this may be that health workers in these countries often are not properly trained to offer the care that these children need.

In poor countries, children often become seriously ill because of conditions such as pneumonia, meningitis and diarrhoea, and may need emergency care. For newborn babies, the most common reason for emergency care is too little oxygen to the baby during birth. If this goes on for too long, the person delivering the baby has to help the baby breathe, and sometimes has to get the baby’s heart rate back to normal. This is called neonatal resuscitation.

Neonatal resuscitation is a skilled task, and the health worker needs proper training. As babies need to be resuscitated quickly, the health worker needs to know how to prepare for this before the baby is born. For instance, he or she needs to know how to prepare the room and proper equipment. Health workers in poor countries often do not have these skills, and these babies are likely to die. Babies can also be harmed if the health worker does not resuscitate the baby correctly.

Several training programmes have been developed to teach health workers how to give emergency care to seriously ill babies and children. But most of these have been developed and tested in wealthy countries, and we don’t know whether they would work in poor countries.

What happens when health professionals in poor countries are given extra training?

The review authors found two relevant studies. These studies compared the practices of health professionals who had been given extra training in the care of newborns with the practices of health professionals who did not receive extra training.

In the first study, nurses at a maternity hospital in Kenya completed a one‐day training course on how to resuscitate newborn babies. This course was adapted from the UK Resuscitation Council, and it included lectures and practical training. The study suggests that after these training courses:

• health professionals are probably more likely to resuscitate newborn babies correctly (moderate certainty of the evidence); and

• newborn babies may be less likely to die while being resuscitated (low certainty of the evidence).

In the second study, doctors, nurses and midwives in five Sri Lankan hospitals were given a four‐day training course on how to prepare for and provide care for newborns. This course was adapted from the World Health Organization (WHO) Training Modules on Essential Newborn Care and Breastfeeding, and included lectures, demonstrations, hands‐on training and small group discussions. This study suggests that after these training courses:

• health professionals probably are more likely to be well prepared to resuscitate newborn babies (moderate certainty of the evidence).

Unfortunately, the two studies followed up with health professionals for only two to three months after they received training. We therefore don’t know if the benefits of the training courses lasted over time.

The review authors found no studies that looked at the effects of training programmes on the care of older children.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

Review authors searched for studies that had been published up to February 2015.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| In‐service neonatal emergency care training versus usual care for healthcare professionals | |||||

|

Population: nurses and midwives Setting: delivery room/theatre (Kenya) Intervention: 1‐day newborn resuscitation training Comparison: usual care | |||||

| Outcomes | Absolute effect* (95% CI) |

Relative effect (95% CI) |

Number of resuscitation practices (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE)¶ | |

| Without training (usual care) | With in‐service training | ||||

|

Health workers' resuscitation practices: proportion of adequate initial resuscitation practices Direct observation Follow‐up: 50 days |

27 per 100 | 66 per 100 (47 to 92) | RR 2.45 (1.75 to 3.42) | 212 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝a* Moderate |

| Difference: 39 more adequate resuscitation practices per 100 resuscitation practices (from 20 more to 65 more) | |||||

|

Health workers' resuscitation practices: inappropriate and potentially harmful practices per resuscitation Direct observation Scale: 0 to 1 (better indicated by lower values) Follow‐up: 50 days |

Mean: 0.92 | Mean: 0.53 Mean difference: 0.40 (0.13 to 0.66) |

‐ | 212 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝a* Moderate |

|

Neonatal mortality in all resuscitation episodes Medical records (resuscitation observation sheet) Follow‐up: 50 days |

36 per 100 | 28 per 100 (14 to 53) | RR 0.77 (0.40 to 1.48) | 90 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝a,b* Low |

| Difference: 8 fewer deaths per 100 resuscitation episodes (from 22 fewer to 17 more) | |||||

| CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; GRADE: GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. *The risk WITHOUT the intervention is based on control group risk. The corresponding risk WITH the intervention (and the 95% confidence interval for the difference) is based on the overall relative effect (and its 95% confidence interval). | |||||

|

aDowngraded from high to moderate because of risk of bias (details about allocation sequence generation and concealment were not reported in the article; potential cross‐group contamination cannot be excluded). bDowngraded from moderate to low because of imprecision (few events, N = 27 deaths). *See Appendix 2 for evidence profile (detailed judgements on certainty of evidence). | |||||

| About the certainty of the evidence (GRADE).† High: This research provides a very good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different‡ is low. Moderate: This research provides a good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different‡ is moderate. Low: This research provides some indication of the likely effect. However, the likelihood that it will be substantially different‡ is high. Very low: This research does not provide a reliable indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different‡ is very high. †This is sometimes referred to as ‘quality of evidence’ or ‘confidence in the estimate’. ‡Substantially different = a large enough difference that it might affect a decision. | |||||

2.

| In‐service neonatal emergency care training versus standard care for healthcare professionals | ||||

|

Participants: doctors, nurses and midwives Settings: delivery room (Sri Lanka) Intervention: 4‐day essential newborn care training Comparison: usual care | ||||

| Outcomes | Absolute effect* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE)†¶ | |

| Without training (usual care) | With in‐service training | |||

|

Preparedness for resuscitation‡ Scale: 0 to 100% (better indicated by higher values) Follow‐up: 90 days |

Mean percentage: 10.46% | Mean percentage: 19.29% Mean percentage change: 8.83% (6.41% to 11.25%) |

‐ | ⊕⊕⊕⊝a§ Moderate |

| CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; GRADE: GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. * The risk WITHOUT the intervention is based on the control group risk. The corresponding risk WITH the intervention (and the 95% confidence interval for the difference) is based on the overall relative effect (and its 95% confidence interval). | ||||

| †About the certainty of the evidence (GRADE).¶ High: This research provides a very good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different# is low. Moderate: This research provides a good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different# is moderate. Low: This research provides some indication of the likely effect. However, the likelihood that it will be substantially different# is high. Very low: This research does not provide a reliable indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different# is very high. ‡Improvement also observed in assessment of breathing (however, re‐analysis to calculate intervention effect was not done owing to baseline imbalance between study groups). §See Appendix 3 for evidence profile (detailed judgements of certainty of evidence). ¶This is sometimes referred to as ‘quality of evidence’ or ‘confidence in the estimate’. #Substantially different = a large enough difference that it might affect a decision. | ||||

| aDowngraded from high to moderate because of risk of bias (methods of allocation sequence generation and concealment were not reported; 'unit of analysis error' was present). | ||||

Background

In low‐income countries, most deaths among seriously ill children who come into contact with referral level health services occur within 48 hours of when they are seen (Berkley 2005). It is possible that good quality immediate and effective care provided by health professionals could reduce these deaths (Nolan 2001). Provision of appropriate care however depends on the presence of skilled health personnel at the point of care delivery (WHO 2005). To improve health workers' capacity to provide effective care for seriously ill newborns and children in low‐income countries, various in‐service training courses, based mainly on models of high‐income countries, are proposed. This is the first update of the original review.

Description of the condition

Severe illness remains a leading cause of newborn and child deaths in low‐income countries (LICs) (Liu 2012; Seale 2014). Major conditions contributing to severe illness include sepsis, pneumonia, meningitis and diarrhoea (Liu 2012; Seale 2014). Early recognition of severe illness with prevention of cardiorespiratory arrest through resuscitation represents a critical step towards reducing mortality and long‐term disability in seriously ill newborns and children. However, the clinical diagnosis of severe illness can be difficult, as signs are often non‐specific and deteriorate rapidly.

Description of the intervention

A variety of in‐service emergency courses for care of seriously ill newborns and children are available. These courses include (1) neonatal life support courses (e.g. Newborn Life Support (NLS), Neonatal Resuscitation Programme (NRP)); (2) paediatric life support courses (e.g. Paediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS), Paediatric Life Support (PLS)); (3) life support/emergency care elements within the Integrated Management of Pregnancy and Childbirth programme (e.g. Essential Newborn Care (ENC)); and (4) components of other in‐service child health training courses that deal with the care of children with serious illness (e.g. Emergency Triage, Assessment and Treatment (ETAT), Control of Diarrheal Diseases (CDD), and Acute Respiratory Infection (ARI) case management programmes; training components of the Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) strategy) (Table 3).

1. Summary of in‐service neonatal and paediatric emergency care courses*.

| Course | Content | Duration (days) | Target audience |

| Neonatal Life Support (NLS) | Neonatal resuscitation | 1 | Midwives, paediatricians, general practitioners |

| Neonatal Resuscitation Programme (NRP) | Neonatal resuscitation | 1 | Midwives, paediatricians, general practitioners |

| Paediatric Life Support (PLS) | Basic Life Support (BLS) and Advanced Life Support (ALS) for children; recognition of paediatric emergencies | 1 | Nurses and doctors involved in paediatric care |

| Paediatric Advanced Life Support (PALS) | BLS and ALS for children; recognition of paediatric emergencies; some neonatal life support | 2 | Nurses and doctors involved in paediatric care |

| Prehospital Paediatric Life Support (PHPLS) | Prehospital paediatric emergency care | 2+ | General practitioners, paramedics, some nurses, emergency medicine staff |

| Advanced Paediatric Life Support (APLS) | BLS and ALS for children; paediatric emergencies, including serious illness and major trauma, some neonatal life support | 3 | Paediatricians, emergency medicine doctors, some anaesthetists, senior paediatric nurses |

| Emergency Triage Assessment and Treatment (ETAT) | Very ill children presenting to hospital | 3.5 | Doctors, nurses, paramedics |

| Essential Newborn Care Course (ENC) | Aspects of newborn care (including neonatal resuscitation) in the Integrated Management of Pregnancy and Childbirth (IMPAC) | 5 | Nurses, midwives, doctors |

| Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) | Ill children and neonates including emergency care or identification and referral of the seriously ill | 11 | Nurses, midwives, doctors |

Although such formalised educational programmes vary in origin, scope and target audience, they typically are aimed at in‐service rather than preservice training, and are short and intensive with a structured approach to presentation of the clinical subject. The one‐day NRP course was first taught in 1987 in the USA, and the one‐day NLS course was initiated in the UK in 2001 (Raupp 2007). PALS, a two‐day course, was piloted in the USA in 1988. Advanced Paediatric Life Support (APLS), a three‐day course, was developed and piloted in the UK in 1992. Two other courses ‐ the one‐day PLS course and Prehospital PLS ‐ have been designed to complement the APLS (Jewkes 2003). The World Health Organization (WHO) has added to this list the three and one‐half‐day ETAT course based on and validated against the APLS course in Malawi (Gove 1999; Molyneux 2006). This course is specifically aimed at low‐income countries and is intended to improve prompt identification and institution of life‐saving emergency treatment for very ill children.

The more general CDD and ARI programmes were developed by the WHO in 1980, in recognition of high childhood mortality due to diarrhoea/dehydration and pneumonia among very ill neonates and children; they focus on case management training rather than life support (Forsberg 2007; Pio 2003). Although these courses concentrate on community‐based or out‐patient‐based management, with good evidence for their success (Sazawal 2001), they also include guidance on management of very severe illness. These disease‐specific training approaches were incorporated into the broader package of the IMCI strategy. Here the particular focus for management of the very ill child is the decision to provide prereferral care and referral to hospital. In addition to this, the WHO has developed a specific five‐day course on hospital management of severe malnutrition (WHO 2002).

How the intervention might work

The effectiveness of in‐service training of healthcare professionals depends on changes in health worker practices, which, plausibly, should precede any impact on mortality or morbidity.

Why it is important to do this review

In‐service training costs both time and money, for example, the cost of the two‐day European Paediatric Life Support (EPLS) course is estimated to be about USD 190 per trainee in Kenya (personal communication with ME, 2009). Apart from the sometimes high costs of providing courses (often recovered in high‐income countries with high course fees), attendance at such courses often means that important staff are absent from their normal duties with potential disruption to patient care and, for some, loss of personal income (Jabbour 1996). Despite their high costs, emergency care courses remain a thriving enterprise in many high‐income countries, as is reflected in their ever increasing number and variety (Jewkes 2003). In the hope that they might improve the quality of care in low‐ and middle‐income countries, considerable global efforts and investments have gone into further development, refinement and adaptation of these courses to meet the needs of individual countries (Baskett 2005). Yet despite these investments and the faith placed in them by many organisations and institutions, evidence of their effectiveness in improving treatment of seriously ill newborns and children remains unclear. Several studies on in‐service emergency care training for newborns and children have been completed since our original review was published, in 2010. Therefore an updated review of the effectiveness of these courses is needed.

Objectives

To assess the effects of in‐service emergency care training on health professionals' treatment of seriously ill newborns and children in low‐income countries.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised trials, non‐randomised trials, controlled before‐after studies and interrupted‐time‐series studies were eligible for inclusion (EPOC 2014). We excluded community‐based studies.

Types of participants

Qualified healthcare professionals (doctors, nurses, midwives, physician assistants) in outpatient/hospital‐based settings responsible for care of seriously ill newborns and children were eligible for inclusion. We excluded non‐qualified healthcare providers (e.g. medical students/trainees, medical interns, community health workers). We did not exclude studies on the basis of their income classification (low, middle or high income).

Types of interventions

In‐service training courses aimed at changing health provider behaviour in the care of seriously ill newborns and children were eligible for inclusion (Table 3).

Neonatal life support courses (e.g. NLS, NRP).

Paediatric life support courses (e.g. PALS, PLS).

Life support elements within the Integrated Management of Pregnancy and Childbirth (e.g. ENC).

Other in‐service newborn and child health training courses aimed at recognition and management of seriously ill newborns and children (e.g. ETAT, CDD, ARI, malaria case management, training components of IMCI strategy).

We excluded studies of complex training interventions in which training was combined with and was impossible to separate from additional health system changes (e.g. improved staffing, health facility reorganisation).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

We included studies only if they reported objectively measured health professional (in practice) performance outcomes (e.g. clinical assessment/diagnosis, recognition and management/referral of seriously ill newborn/child, prescribing practices).

Secondary outcomes

We also considered the following outcomes when reported.

Participant outcomes (e.g. mortality, morbidity).

Health resource utilisation (e.g. drug use, laboratory tests).

Health services utilisation (e.g. length of hospital stay).

Other markers of clinical performance (e.g. simulated health worker performance in practice settings).

Training/implementation costs.

Impact on equity.

Adverse effects.

We excluded studies that reported only other markers of performance/simulations/skill testing done outside practice settings/in classrooms (e.g. practicing/demonstrating resuscitation techniques using a dummy). We considered for inclusion simulations of emergency care in practice settings that were designed to reflect real practice.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases for related reviews.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (2015, Issue 2), part of The Cochrane Library (www.cochranelibrary.com) (searched 24/02/2015).

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (2015, Issue 1), part of The Cochrane Library (www.cochranelibrary.com) (searched 24/02/2015).

Health Technology Assessment Database (HTA) (2015, Issue 1), part of The Cochrane Library (www.cochranelibrary.com) (searched 24/02/2015).

We searched the following databases for primary studies.

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2015, Issue 1), part of The Cochrane Library (www.cochranelibrary.com) (including the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Register) (searched 24/02/2015).

MEDLINE In‐Process and Other Non‐Indexed Citations, and MEDLINE daily, MEDLINE and OLDMEDLINE, 1946 to present, Ovid SP (searched 23/02/2015).

EMBASE, 1980 to 2015 Week 08, Ovid SP (searched 23/02/2015).

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), 1981 to present, EBSCOHost (searched 24/02/2015).

Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), 1966 to present, ProQuest (searched 24/02/2015).

World Health Organization Library Information System (WHOLIS), WHO (searched 24/02/2015).

Latin American Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (LILACS), VIrtual Health Library (VHL) (searched 24/02/2015).

Science Citation Index, 1975 to present; Social Sciences Citation Index, 1975 to present; Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) Web of Science (searched 24/02/2015) for papers that cite included studies.

We developed search strategies for electronic databases using the methodological component of the EPOC search strategy combined with selected Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and free‐text terms. We applied no date, language or publication status restrictions. See Appendix 1 for strategies used.

Searching other resources

We also searched clinical trial registries (https://clinicaltrials.gov/, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP, http://www.who.int/ictrp/en/), both searched 11/02/2014) and websites of relevant organisations (Helping Babies Breathe, http://www.helpingbabiesbreathe.org/, searched 11/02/2014). We used a combination of search terms derived from the MEDLINE search strategy. In addition, we screened reference lists of related reviews.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Review authors (NO and ME) independently screened the titles, abstracts and full texts of retrieved articles and applied the predefined study eligibility criteria to select studies. We resolved disagreements through discussion.

Data extraction and management

Review authors (NO and ME) independently extracted the following data using a modified EPOC data collection tool (EPOC 2014). We resolved disagreements by discussion.

Study characteristics (e.g. study design, sample size, setting).

Participants (e.g. number of healthcare providers randomly assigned, number of practices performed).

Intervention (e.g. type and duration of training courses)/co‐interventions.

Targeted health provider behaviour (e.g. resuscitation practices).

Outcome measures (e.g. proportion of providers with the event of interest in study groups).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Review authors (NO and ME) independently assessed study risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (Higgins 2011). Quality domains assessed included allocation sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessors, completeness of participant follow‐up, handling of incomplete outcome data, protection against selective outcome reporting and contamination. We classified findings into three categories: low (low risk of bias for all key quality domains), high (high risk of bias for one or more key domains) and unclear risk of bias (unclear risk of bias for one or more key domains). We did not exclude studies on the basis of their risk of bias.

Data synthesis

Included studies assessed different interventions and outcomes. Meta‐analysis was therefore inappropriate. We undertook a structured synthesis of results.

In Senarath 2007, a unit of analysis error occurred; hospitals were randomly assigned and performance at deliveries was analysed, without adjustment for clustering. In addition, outcomes in intervention and control groups were not directly compared (comparisons were made within comparison groups before and after the intervention). Re‐analysis was possible for only one outcome ‐ preparedness for resuscitation ‐ for which baseline levels of resuscitation practices were comparable between study groups. In the re‐analysis, we assessed training effect by computing mean differences in outcomes, using reported standard deviations to estimate standard errors. To account for clustering, we assumed an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.015 (with a design effect of 1.129) that was based on published data (Rowe 2002).

Review authors (NO and ME) independently assessed the certainty of evidence for each outcome using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system (Guyatt 2008). This approach classifies the certainty of evidence (defined as ‘the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is correct’) into one of four categories ('high', 'moderate', 'low' or 'very low'). We resolved disagreements on certainty ratings by discussion. We did not exclude studies on the basis of their GRADE certainty ratings; we took into account the certainty of evidence when synthesising overall findings. We report the results of certainty assessments in the 'Summary of findings tables' section.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

In the original review, 2480 references were identified. Of these, 2334 articles were excluded following a review of titles and abstracts. Reasons for exclusion included inappropriate study designs/interventions/outcomes; enrolment of trainee/community health workers; and enrolment of non‐paediatric patients. The full texts of 146 papers were retrieved for detailed eligibility assessment. Of these, eight studies were identified as potentially meeting the review inclusion criteria. Six were subsequently excluded. Overall, two studies were included: Opiyo 2008 and Senarath 2007.

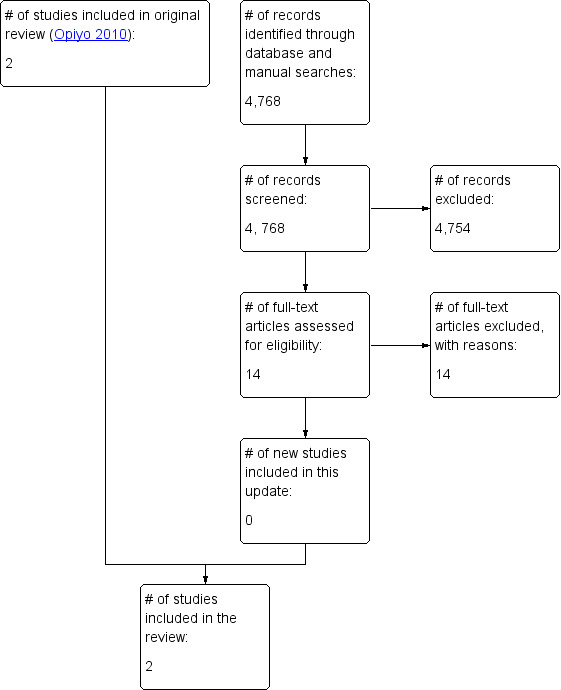

In this review update, we identified a total of 4768 articles. We excluded 4754 articles after a review of titles and abstracts. We retrieved the full texts of 14 articles for detailed assessment. Of these, 14 articles were excluded because of ineligible study design or setting (n = 7 studies), participants (n = 1 study) and outcomes (n = 6 studies). We identified no ongoing studies. No new studies met all of the review eligibility criteria. The study flow diagram is presented in Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Both studies were randomised trials done in delivery rooms/theatres in Kenya (Opiyo 2008) and Sri Lanka (Senarath 2007). Healthcare providers were nurses in Opiyo 2008 and were mixed (doctors, nurses, midwives) in Senarath 2007. Targeted behaviours included newborn resuscitation (Opiyo 2008) and general management/preparation and conduct of delivery care for newborns (Senarath 2007). Postintervention data were collected over a period of 50 days in Opiyo 2008 and three months in Senarath 2007. Individual healthcare providers (n = 83) were randomly assigned in Opiyo 2008, and hospitals (n = 5) were randomly assigned in Senarath 2007. Both studies were adequately powered (90%) for primary outcomes. Neither study examined training/implementation costs.

Opiyo 2008 assessed the effects of one‐day newborn resuscitation training on health worker resuscitation practices in a maternity hospital in Kenya. The course, which was adapted from the UK Resuscitation Council,presented an A (airway), B (breathing), C (circulation) approach to resuscitation and laid down a clear step‐by‐step strategy for the first minutes of resuscitation at birth. Training included focused lectures and practical scenario sessions in which infant manikins were used. Participants were provided a course manual two weeks before training for self learning. Participants were randomly allocated to receive early training (n = 28) or late training (control group, n = 55). Data were collected on 97 and 115 resuscitation episodes over seven weeks after early and late training, respectively.

Senarath 2007 assessed the effects of four‐day essential newborn care training on health provider practices in hospitals in Sri Lanka. The course was adapted from the WHO Training Modules on Essential Newborn Care and Breastfeeding. Participants were provided teaching aids on newborn care and resuscitation. Training comprised lectures, demonstrations, hands‐on training and small group discussions. Hospitals were randomly assigned to intervention (n = 2 hospitals) and control groups (n = 3 hospitals). The main sample for data collection by exit interview included 446 mother/newborn pairs before intervention and 446 pairs after intervention (223 each in intervention and control groups). These exit interview data were not relevant to the topic of this review. Direct observations of delivery practices were made on a subsample consisting of 96 healthcare providers (48 before and 48 after the intervention). Postintervention data collection commenced three months after training.

Excluded studies

We eventually excluded 20 studies that initially met the review eligibility criteria. These are listed in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Six studies were excluded in the original review: Bryce 2005, a non‐randomised controlled study on health facility IMCI training, was excluded, as the training intervention was combined with and was impossible to separate from concurrent district health strengthening activities (skills reinforcement through supervised clinical practice). El‐Arifeen 2004, a cluster‐randomised trial on the effects of IMCI training on quality of care, was excluded, as data on referral rate (appropriate health worker response to an encounter with a seriously ill child and our outcome of interest) were not reported for seriously ill children. Gouws 2004, a cluster‐randomised trial on the effects of IMCI training on health worker antibiotic use, was excluded, as no baseline assessment of outcomes was performed. Nadel 2000, an intervention study of periodic mock resuscitations combined with an eight‐hour resuscitation course, was excluded, as it lacked a concurrent comparison group/used a historical control group. Two further studies were excluded, as they enrolled only apparently well children (Pelto 2004) or those with mild acute respiratory infection episodes (Ochoa 1996).

In this update, we excluded 14 studies because of ineligible designs (non‐randomised designs, uncontrolled before‐after designs, community‐based settings) (n = 6 studies) and inappropriate outcome measures/simulated provider practices (n = 8 studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

Both randomised trials had serious limitations. In Opiyo 2008, allocation sequence generation, concealment, blinding of outcome assessors, follow‐up of health providers and reporting of outcome measures were adequate (however, details about allocation sequence generation and concealment were not reported in the article). Potential cross‐group contamination in the trial cannot be excluded. In Senarath 2007, outcome data were completely reported and the study was adequately protected against contamination and selective outcome reporting. However, methods of allocation sequence generation and concealment were not reported. Baseline differences in health providers and outcomes were evident between study groups. Blinding of outcome assessment was inadequate, and the presence of a 'unit of analysis error' added further uncertainty regarding the results.

Effects of interventions

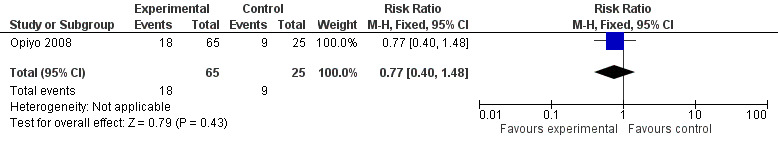

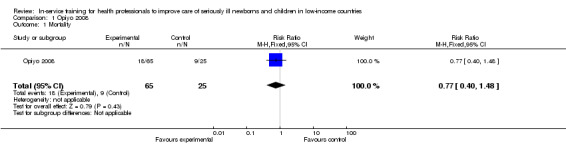

In Opiyo 2008, newborn resuscitation training improved health workers' resuscitation practices (trained 66% vs control 27%; risk ratio (RR) 2.45, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.75 to 3.42) (moderate certainty evidence). Training also reduced the frequency of inappropriate/harmful resuscitation practices (trained 0.53 vs control 0.92; mean difference (MD) 0.40, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.66; Appendix 2) (moderate certainty evidence). Effects on neonatal mortality were inconclusive (trained 0.28 vs usual care 0.25; RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.40 to 1.48; N = 27 deaths; Figure 2) (low certainty evidence).

2.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Opiyo 2008, outcome: 2.1 Mortality.

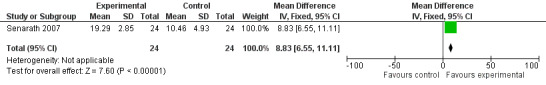

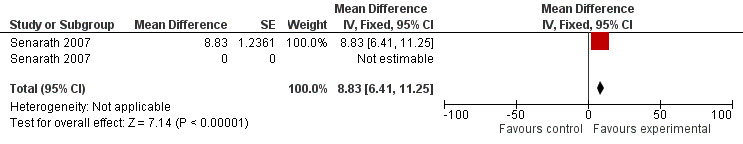

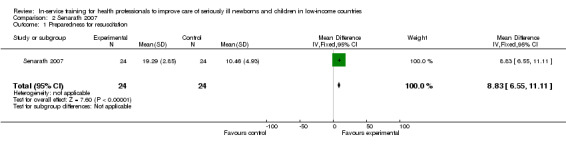

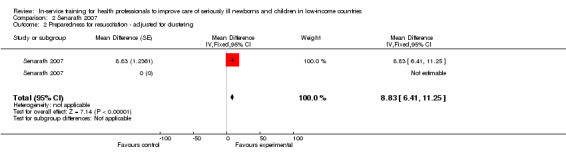

In Senarath 2007, assessment of breathing of the newborn at birth and four of the five components of essential newborn care practices were improved in the intervention group after training, but it was possible to re‐analyse the data to compare intervention and control groups and to adjust for clustering for only one outcome: preparedness for resuscitation. Findings suggest that essential newborn care training probably slightly improves resuscitation preparedness (mean percentage change 8.83%, 95% CI 6.41% to 11.25%; Figure 3 and Figure 4) (moderate certainty evidence).

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Senarath 2007, outcome: 1.1 Practice of preparedness of resuscitation. Mean difference = mean percentage change.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Senarath 2007, outcome: 1.2 Preparedness for resuscitation ‐ adjusted for clustering. Mean difference = mean percentage change.

Discussion

This review found few well‐conducted studies on the effects of in‐service training aimed at improving care of the seriously ill newborn. Findings from the two included studies suggest a beneficial effect on health provider outcomes (resuscitation practices, assessment of breathing, resuscitation preparedness) in the short term. However, effects on neonatal mortality were inconclusive (although the only study that reported this outcome was underpowered to detect a mortality effect). Even though both included studies reported improvement in health provider practices after training, a generalisable conclusion of effectiveness cannot be inferred given the sparse data available and differences between training interventions and outcomes examined.

Reported benefits should be interpreted with caution. First, in Opiyo 2008, assessment of outcomes was conducted immediately after training for a short period (50 days). Therefore instantaneous improvement in provider performance could have been expected. Clinical skills have been shown to 'decay' over time, with as much as a 50% reduction in appropriate practice (as assessed in classroom simulations) within six months of intense training (McKenna 1985). Assessment of training effects over a longer time could have improved our confidence in the results. The potential for a ‘decay effect’ underscores the need for periodic refresher training to maintain recommended provider practice. Second, in Senarath 2007, a large number of health providers demonstrated appropriate newborn care practices at baseline. The narrow ‘performance improvement' gap possibly limited demonstration of the real impact of the training. Third, training coverage was low in Opiyo 2008 and unclear in Senarath 2007. Saturation training to the level of that reported in one excluded study (94%) (El‐Arifeen 2004) can potentially create a ‘herd effect’ on provider practices. Thus, possible mediation of reported effects by level of training coverage cannot be excluded. Finally, none of the included studies examined implementation costs. Thus, whether the observed benefits of training interventions are worth the costs remains uncertain.

The duration of training courses was varied (one‐day vs four‐day course). Apart from the clear effect on costs, training duration may modify their impact: One review (Rowe 2008) (n = 2 studies) found marginal effectiveness of standard IMCI training (≥ 11 days) compared with shortened IMCI training (five to 11 days). The complexity of the targeted behaviour may also modify training effects: Practices such as holding the baby upside during resuscitation may be easier to change than complex ones such as performing bag‐valve‐mask resuscitation. In Opiyo 2008, the teaching strategy consisted of focused lectures and practical scenario sessions using an infant manikin, and in Senarath 2007, the strategy involved lectures, demonstrations, hands‐on training and small group discussions. The format of training courses could influence their effect: One review found mixed interactive and didactic/lecture‐based educational meetings to be more effective than didactic meetings or interactive meetings (Forsetlund 2009).

The limited available evidence can be explained by several factors. First, a large number of studies were excluded on the basis of weak design (lack of appropriate controls, retrospective surveys). Most of the available evidence is therefore unreliable because of high risk of bias. Second, the lack of rigorous studies could be due to design and ethical challenges in the evaluation of educational interventions in practice settings. Desirable features such as protection against contamination cannot be fully achieved within routine clinical settings. In addition, random assignment of health providers and sick babies to a control arm and observation of practices performed by untrained providers raise clear ethical concerns. Third, effective sample sizes will always be difficult to achieve, as severe illness episodes and resuscitation events remain relatively uncommon events in practice. Large multi‐centre studies with relatively long observation periods would be needed to effectively assess the effects of emergency care courses. Apart from high costs, such studies would have to contend with the difficulty of securing continued availability and participation of health providers.

Findings of the present review are consistent with those of previous reviews (Jabbour 1996; Rowe 2008), which found limited evidence on the effectiveness of in‐service neonatal and paediatric emergency care courses.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The findings of this review suggest that in‐service neonatal care courses probably improve health professional practices in caring for seriously ill newborns. Decisions to scale up these courses in low‐income countries must be based on consideration of costs and logistics associated with their implementation, including the need for adequate numbers of skilled instructors, appropriate locally adapted training materials and the availability of basic resuscitation equipment.

Implications for research.

Large pragmatic multi‐centre randomised trials (with appropriate controls and adequate randomisation procedures) evaluating the impact of emergency care in‐service training on long‐term outcomes (health professional practices and patient outcomes) are needed (given the current uncertainty on how long short‐term benefits are retained, particularly in settings in which they are used infrequently).

Such trials should:

involve direct head‐to‐head comparison of courses of varied length (e.g. one‐day vs four‐day courses);

aim to include children (in both out‐patient and hospital settings);

be preceded by pilot cost impact evaluation studies (given current uncertainty regarding the economic consequences of in‐service emergency care training); and

collect data on resource use and cost of training implementation (to optimise appropriate policy decisions regarding which interventions are worthy of investment).

To facilitate implementation and replication, studies should provide sufficient detail regarding their content (e.g. need for equipment, teamwork) and format (e.g. small group interactive vs lecture, hands‐on skills with dummies). Further studies are needed to determine optimal refresher training intervals for in‐service emergency care courses.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 10 March 2015 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | We have included no new studies in this update. |

| 10 March 2015 | New search has been performed | This is the first update of the original review. We conducted a new search and updated content. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2008 Review first published: Issue 4, 2010

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 22 March 2010 | Amended | We have made minor edits. |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Marit Johansen for help with the literature searches and Andy Oxman for advice on the update process. NO is supported by funding from a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award (#084538). ME is funded by a Wellcome Trust Senior Fellowship (#097170).

Appendices

Appendix 1. Detailed search strategies

CDSR, The Cochrane Library

| ID | Search | Hits |

| #1 | MeSH descriptor: [Inservice Training] explode all trees | 567 |

| #2 | MeSH descriptor: [Health Personnel] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Education ‐ ED] | 1112 |

| #3 | MeSH descriptor: [Internship and Residency] this term only | 763 |

| #4 | (staff or employee* or clinician* or physician* or nurse* or midwif* or midwives or pharmacist* or specialist* or practitioner* or dietician* or dietitian* or nutritionist*) next (train* or course* or development or education or teach*):ti,ab,kw | 840 |

| #5 | (inservice or "in service" or "life support") near/2 (train* or course* or development or education or teach*):ti,ab,kw | 709 |

| #6 | ("on the job training" or internship or residency):ti,ab,kw | 1071 |

| #7 | (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6) | 3354 |

| #8 | MeSH descriptor: [Case Management] this term only | 651 |

| #9 | MeSH descriptor: [Critical Care] explode all trees | 1861 |

| #10 | MeSH descriptor: [Life Support Care] this term only | 85 |

| #11 | MeSH descriptor: [Critical Illness] this term only | 1232 |

| #12 | MeSH descriptor: [Acute Disease] this term only | 8984 |

| #13 | MeSH descriptor: [Emergency Medical Services] explode all trees | 2992 |

| #14 | MeSH descriptor: [Emergency Medicine] this term only | 216 |

| #15 | MeSH descriptor: [Emergency Treatment] explode all trees | 4066 |

| #16 | MeSH descriptor: [Emergency Nursing] this term only | 58 |

| #17 | "case management":ti,ab,kw | 1289 |

| #18 | (emergency near/2 (service* or medicine or nursing or triage)):ti,ab,kw | 3885 |

| #19 | "life support":ti,ab,kw | 484 |

| #20 | resuscitation:ti,ab,kw | 2730 |

| #21 | "first aid":ti,ab,kw | 129 |

| #22 | ((referral or urgent) near/2 care):ti,ab,kw | 573 |

| #23 | (critical* or emergency or intensive or serious* or sever* or acute*) near/2 (care or ill or illness* or treatment or therap* or disease*):ti,ab,kw | 62061 |

| #24 | (#8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23) | 69565 |

| #25 | MeSH descriptor: [Child] explode all trees | 135 |

| #26 | MeSH descriptor: [Infant] explode all trees | 13304 |

| #27 | MeSH descriptor: [Child Care] explode all trees | 867 |

| #28 | MeSH descriptor: [Pediatrics] explode all trees | 546 |

| #29 | MeSH descriptor: [Pediatric Nursing] explode all trees | 253 |

| #30 | MeSH descriptor: [Perinatal Care] this term only | 124 |

| #31 | MeSH descriptor: [Infant Death] this term only | 0 |

| #32 | MeSH descriptor: [Perinatal Death] this term only | 0 |

| #33 | (child* or infant* or pediatric* or paediatric* or perinat* or newborn* or new next born* or neonat* or baby or babies or kid or kids or toddler*):ti,ab,kw | 105756 |

| #34 | (#25 or #26 or #27 or #28 or #29 or #30 or #31 or #32 or #33) | 105756 |

| #35 | MeSH descriptor: [Pediatrics] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Education ‐ ED] | 155 |

| #36 | MeSH descriptor: [Pediatric Nursing] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Education ‐ ED] | 36 |

| #37 | (#35 or #36) | 188 |

| #38 | MeSH descriptor: [Emergency Medicine] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Education ‐ ED] | 86 |

| #39 | MeSH descriptor: [Emergency Nursing] this term only and with qualifier(s): [Education ‐ ED] | 9 |

| #40 | #38 or #39 | 95 |

| #41 | MeSH descriptor: [Intensive Care, Neonatal] this term only | 275 |

| #42 | MeSH descriptor: [Diarrhea, Infantile] this term only | 455 |

| #43 | MeSH descriptor: [Infant, Newborn, Diseases] explode all trees | 4391 |

| #44 | ("Acute Respiratory Infection" or "Acute Respiratory Infections"):ti,ab,kw | 287 |

| #45 | (#41 or #42 or #43 or #44) | 5308 |

| #46 | ("Control of Diarrheal Disease" or "Control of Diarrheal Diseases"):ti,ab,kw | 2 |

| #47 | Neonatal next Resuscitation next Program*:ti,ab,kw | 30 |

| #48 | "Essential Newborn Care":ti,ab,kw | 22 |

| #49 | "Integrated Management of Childhood Illness":ti,ab,kw | 26 |

| #50 | (#46 or #47 or #48 or #49) | 76 |

| #51 | #7 and #24 and #34 | 140 |

| #52 | #24 and #37 | 50 |

| #53 | #34 and #40 | 23 |

| #54 | #7 and #45 | 20 |

| #55 | #50 or #51 or #52 or #53 or #54 in Cochrane Reviews (Reviews and Protocols) | 14 |

CENTRAL; DARE; HTA, The Cochrane Library

| ID | Search | Hits |

| #1 | MeSH descriptor: [Inservice Training] explode all trees | 567 |

| #2 | MeSH descriptor: [Health Personnel] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Education ‐ ED] | 1112 |

| #3 | MeSH descriptor: [Internship and Residency] this term only | 763 |

| #4 | (staff or employee* or clinician* or physician* or nurse* or midwif* or midwives or pharmacist* or specialist* or practitioner* or dietician* or dietitian* or nutritionist*) next (train* or course* or development or education or teach*) | 1507 |

| #5 | (inservice or "in service" or "life support") near/2 (train* or course* or development or education or teach*) | 755 |

| #6 | ("on the job training" or internship or residency) | 1318 |

| #7 | (#1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6) | 4091 |

| #8 | MeSH descriptor: [Case Management] this term only | 651 |

| #9 | MeSH descriptor: [Critical Care] explode all trees | 1861 |

| #10 | MeSH descriptor: [Life Support Care] this term only | 85 |

| #11 | MeSH descriptor: [Critical Illness] this term only | 1232 |

| #12 | MeSH descriptor: [Acute Disease] this term only | 8984 |

| #13 | MeSH descriptor: [Emergency Medical Services] explode all trees | 2992 |

| #14 | MeSH descriptor: [Emergency Medicine] this term only | 216 |

| #15 | MeSH descriptor: [Emergency Treatment] explode all trees | 4066 |

| #16 | MeSH descriptor: [Emergency Nursing] this term only | 58 |

| #17 | "case management" | 1625 |

| #18 | (emergency near/2 (service* or medicine or nursing or triage)) | 6233 |

| #19 | "life support" | 582 |

| #20 | resuscitation | 3357 |

| #21 | "first aid" | 181 |

| #22 | ((referral or urgent) near/2 care) | 724 |

| #23 | (critical* or emergency or intensive or serious* or sever* or acute*) near/2 (care or ill or illness* or treatment or therap* or disease*) | 78684 |

| #24 | (#8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23) | 86892 |

| #25 | MeSH descriptor: [Child] explode all trees | 135 |

| #26 | MeSH descriptor: [Infant] explode all trees | 13304 |

| #27 | MeSH descriptor: [Child Care] explode all trees | 867 |

| #28 | MeSH descriptor: [Pediatrics] explode all trees | 546 |

| #29 | MeSH descriptor: [Pediatric Nursing] explode all trees | 253 |

| #30 | MeSH descriptor: [Perinatal Care] this term only | 124 |

| #31 | MeSH descriptor: [Infant Death] this term only | 0 |

| #32 | MeSH descriptor: [Perinatal Death] this term only | 0 |

| #33 | (child* or infant* or pediatric* or paediatric* or perinat* or newborn* or new next born* or neonat* or baby or babies or kid or kids or toddler*) | 120110 |

| #34 | (#25 or #26 or #27 or #28 or #29 or #30 or #31 or #32 or #33) | 120110 |

| #35 | MeSH descriptor: [Pediatrics] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Education ‐ ED] | 155 |

| #36 | MeSH descriptor: [Pediatric Nursing] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Education ‐ ED] | 36 |

| #37 | (#35 or #36) | 188 |

| #38 | MeSH descriptor: [Emergency Medicine] explode all trees and with qualifier(s): [Education ‐ ED] | 86 |

| #39 | MeSH descriptor: [Emergency Nursing] this term only and with qualifier(s): [Education ‐ ED] | 9 |

| #40 | #38 or #39 | 95 |

| #41 | MeSH descriptor: [Intensive Care, Neonatal] this term only | 275 |

| #42 | MeSH descriptor: [Diarrhea, Infantile] this term only | 455 |

| #43 | MeSH descriptor: [Infant, Newborn, Diseases] explode all trees | 4391 |

| #44 | ("Acute Respiratory Infection" or "Acute Respiratory Infections") | 475 |

| #45 | (#41 or #42 or #43 or #44) | 5493 |

| #46 | ("Control of Diarrheal Disease" or "Control of Diarrheal Diseases") | 3 |

| #47 | Neonatal next Resuscitation next Program* | 37 |

| #48 | "Essential Newborn Care" | 30 |

| #49 | "Integrated Management of Childhood Illness" | 38 |

| #50 | (#46 or #47 or #48 or #49) | 99 |

| #51 | #7 and #24 and #34 | 413 |

| #52 | #24 and #37 | 51 |

| #53 | #34 and #40 | 24 |

| #54 | #7 and #45 | 46 |

| #55 | #50 or #51 or #52 or #53 or #54 in Trials | 230 |

| #56 | #50 or #51 or #52 or #53 or #54 in Other Reviews | 25 |

| #57 | #50 or #51 or #52 or #53 or #54 in Technology Assessments | 3 |

MEDLINE, Ovid SP

| # | Searches | Results |

| 1 | exp Inservice Training/ | 24528 |

| 2 | exp Health Personnel/ed [Education] | 47977 |

| 3 | "Internship and Residency"/ | 35999 |

| 4 | ((staff or employee? or clinician? or physician? or nurse* or midwif* or midwives or pharmacist? or specialist? or practitioner? or dietician? or dietitian? or nutritionist?) adj (train* or course? or development or education or teach*)).ti,ab. | 14885 |

| 5 | ((inservice or in‐service or life support) adj2 (train* or course? or development or education or teach*)).ti,ab. | 2872 |

| 6 | on the job training.ti,ab. | 403 |

| 7 | or/1‐6 | 112597 |

| 8 | Case Management/ | 8484 |

| 9 | exp Critical Care/ | 44683 |

| 10 | Life Support Care/ | 7041 |

| 11 | Critical Illness/ | 17499 |

| 12 | Acute Disease/ | 183549 |

| 13 | exp Emergency Medical Services/ | 98322 |

| 14 | Emergency Medicine/ | 10129 |

| 15 | exp Emergency Treatment/ | 95314 |

| 16 | Emergency Nursing/ | 5782 |

| 17 | case management.ti,ab. | 7765 |

| 18 | emergency triage.ti,ab. | 98 |

| 19 | life support.ti,ab. | 8072 |

| 20 | resuscitation.ti,ab. | 39573 |

| 21 | first aid.ti,ab. | 4342 |

| 22 | ((referral or urgent) adj2 care).ti,ab. | 3612 |

| 23 | ((critical* or emergency or intensive or serious* or sever* or acute*) adj2 (care or ill or illness* or treatment or therap*)).ti,ab. | 291118 |

| 24 | or/8‐23 | 656528 |

| 25 | exp Child/ | 1563941 |

| 26 | exp Infant/ | 948338 |

| 27 | exp Child Care/ | 19934 |

| 28 | Pediatrics/ | 41434 |

| 29 | Neonatology/ | 2135 |

| 30 | Perinatology/ | 1623 |

| 31 | Pediatric Nursing/ | 12308 |

| 32 | Perinatal Care/ | 2918 |

| 33 | Neonatal Nursing/ | 3264 |

| 34 | Infant Death/ | 4 |

| 35 | Perinatal Death/ | 14 |

| 36 | (child* or infant? or pediatric? or paediatric? or perinat* or newborn? or new born? or neonat* or baby or babies or kid? or toddler?).ti,ab. | 1556796 |

| 37 | or/25‐36 | 2524543 |

| 38 | exp Child Care/ed [Education] | 65 |

| 39 | Pediatrics/ed [Education] | 5869 |

| 40 | Neonatology/ed [Education] | 231 |

| 41 | Perinatology/ed [Education] | 122 |

| 42 | Pediatric Nursing/ed [Education] | 1939 |

| 43 | Neonatal Nursing/ed [Education] | 405 |

| 44 | or/38‐43 | 8503 |

| 45 | exp Critical Care/ed [Education] | 30 |

| 46 | Life Support Care/ed [Education] | 2 |

| 47 | exp Emergency Medical Services/ed [Education] | 28 |

| 48 | Emergency Medicine/ed [Education] | 3805 |

| 49 | exp Emergency Treatment/ed [Education] | 2374 |

| 50 | Emergency Nursing/ed [Education] | 972 |

| 51 | or/45‐50 | 7031 |

| 52 | Intensive Care, Neonatal/ | 4422 |

| 53 | Diarrhea, Infantile/ | 6498 |

| 54 | Acute Respiratory Infection?.ti,ab. | 2868 |

| 55 | or/52‐54 | 13751 |

| 56 | exp Infant, Newborn, Diseases/ | 144228 |

| 57 | Control of Diarrheal Disease?.ti,ab. | 72 |

| 58 | Neonatal Resuscitation Program*.ti,ab. | 135 |

| 59 | Essential Newborn Care.ti,ab. | 65 |

| 60 | Integrated Management of Childhood Illness.ti,ab. | 253 |

| 61 | or/57‐60 | 516 |

| 62 | 7 and 24 and 37 | 2196 |

| 63 | 24 and 44 | 1201 |

| 64 | 37 and 51 | 1137 |

| 65 | 7 and 55 | 182 |

| 66 | 7 and 24 and 56 | 69 |

| 67 | or/61‐66 | 3589 |

| 68 | randomized controlled trial.pt. | 385110 |

| 69 | controlled clinical trial.pt. | 88641 |

| 70 | pragmatic clinical trial.pt. | 114 |

| 71 | multicenter study.pt. | 179618 |

| 72 | non‐randomized controlled trials as topic/ | 11 |

| 73 | interrupted time series analysis/ | 17 |

| 74 | controlled before‐after studies/ | 25 |

| 75 | (randomis* or randomiz* or randomly).ti,ab. | 586615 |

| 76 | groups.ab. | 1416282 |

| 77 | (trial or multicenter or multi center or multicentre or multi centre).ti. | 156718 |

| 78 | (intervention? or controlled or control group? or (before adj5 after) or (pre adj5 post) or ((pretest or pre test) and (posttest or post test)) or quasiexperiment* or quasi experiment* or evaluat* or effect? or impact? or time series or time point? or repeated measur*).ti,ab. | 6748504 |

| 79 | or/68‐78 | 7556657 |

| 80 | exp Animals/ | 17695852 |

| 81 | Humans/ | 13705040 |

| 82 | 80 not (80 and 81) | 3990812 |

| 83 | review.pt. | 1938147 |

| 84 | meta analysis.pt. | 53216 |

| 85 | news.pt. | 166920 |

| 86 | editorial.pt. | 370013 |

| 87 | comment.pt. | 613174 |

| 88 | cochrane database of systematic reviews.jn. | 10975 |

| 89 | comment on.cm. | 613174 |

| 90 | (systematic review or literature review).ti. | 57343 |

| 91 | or/82‐90 | 6791681 |

| 92 | 79 not 91 | 5187655 |

| 93 | 67 and 92 | 1636 |

EMBASE, Ovid SP

| # | Searches | Results |

| 1 | In Service Training/ | 13956 |

| 2 | Staff Training/ | 9388 |

| 3 | Nurse Training/ | 1372 |

| 4 | Continuing Education/ | 27705 |

| 5 | Professional Development/ | 5127 |

| 6 | Medical Education/ | 180041 |

| 7 | Residency Education/ | 20953 |

| 8 | ((staff or employee? or clinician? or physician? or nurse* or midwif* or midwives or pharmacist? or specialist? or practitioner? or dietician? or dietitian? or nutritionist?) adj (train* or course? or development or education or teach*)).ti,ab. | 18251 |

| 9 | ((inservice or in‐service or life support) adj2 (train* or course? or development or education or teach*)).ti,ab. | 3324 |

| 10 | on the job training.ti,ab. | 472 |

| 11 | or/1‐10 | 254380 |

| 12 | Case Management/ | 8051 |

| 13 | exp Intensive Care/ | 468236 |

| 14 | Critical Illness/ | 21660 |

| 15 | Disease Severity/ | 382573 |

| 16 | Acute Disease/ | 88120 |

| 17 | Injury Severity/ | 9155 |

| 18 | Emergency Medicine/ | 28345 |

| 19 | exp Emergency Treatment/ | 181735 |

| 20 | Emergency Nursing/ | 5225 |

| 21 | case management.ti,ab. | 9205 |

| 22 | emergency triage.ti,ab. | 130 |

| 23 | life support.ti,ab. | 10351 |

| 24 | resuscitation.ti,ab. | 50652 |

| 25 | first aid.ti,ab. | 5023 |

| 26 | ((referral or urgent) adj2 care).ti,ab. | 4817 |

| 27 | ((critical* or emergency or intensive or serious* or sever* or acute*) adj2 (care or ill or illness* or treatment or therap*)).ti,ab. | 381035 |

| 28 | or/12‐27 | 1290485 |

| 29 | exp Child/ | 2059816 |

| 30 | exp Newborn/ | 459451 |

| 31 | exp Child Health Care/ | 65699 |

| 32 | exp Pediatrics/ | 77383 |

| 33 | exp Pediatric Nursing/ | 12018 |

| 34 | exp Postnatal Care/ | 80179 |

| 35 | Perinatal Care/ | 10465 |

| 36 | (child* or infant? or pediatric? or paediatric? or perinat* or newborn? or new born? or neonat* or baby or babies or kid? or toddler?).ti,ab. | 1819970 |

| 37 | or/29‐36 | 2707589 |

| 38 | Newborn Intensive Care/ | 21801 |

| 39 | Newborn Intensive Care Nursing/ | 62 |

| 40 | Pediatric Intensive Care Nursing/ | 124 |

| 41 | Pediatric Advanced Life Support/ | 450 |

| 42 | Infantile Diarrhea/ | 3767 |

| 43 | Acute Respiratory Infection?.ti,ab. | 3176 |

| 44 | or/38‐43 | 29320 |

| 45 | Emergency Medical Services Education/ | 274 |

| 46 | exp Newborn Disease/ | 976796 |

| 47 | Control of Diarrheal Disease?.ti,ab. | 38 |

| 48 | Neonatal Resuscitation Program*.ti,ab. | 161 |

| 49 | Essential Newborn Care.ti,ab. | 81 |

| 50 | Integrated Management of Childhood Illness.ti,ab. | 286 |

| 51 | or/47‐50 | 560 |

| 52 | 11 and 28 and 37 | 3887 |

| 53 | 11 and 44 | 708 |

| 54 | 37 and 45 | 30 |

| 55 | 11 and 28 and 46 | 560 |

| 56 | or/51‐55 | 4600 |

| 57 | Randomized Controlled Trial/ | 360662 |

| 58 | Controlled Clinical Trial/ | 390355 |

| 59 | Quasi Experimental Study/ | 2271 |

| 60 | Pretest Posttest Control Group Design/ | 220 |

| 61 | Time Series Analysis/ | 14979 |

| 62 | Experimental Design/ | 10740 |

| 63 | Multicenter Study/ | 115711 |

| 64 | (randomis* or randomiz* or randomly).ti,ab. | 764795 |

| 65 | groups.ab. | 1779704 |

| 66 | (trial or multicentre or multicenter or multi centre or multi center).ti. | 203366 |

| 67 | (intervention? or controlled or control group? or (before adj5 after) or (pre adj5 post) or ((pretest or pre test) and (posttest or post test)) or quasiexperiment* or quasi experiment* or evaluat* or effect? or impact? or time series or time point? or repeated measur*).ti,ab. | 8028100 |

| 68 | or/57‐67 | 8974919 |

| 69 | Nonhuman/ | 4453670 |

| 70 | editorial.pt. | 463033 |

| 71 | (systematic review or literature review).ti. | 68545 |

| 72 | "cochrane database of systematic reviews".jn. | 3777 |

| 73 | or/69‐72 | 4952684 |

| 74 | 68 not 73 | 6996420 |

| 75 | 56 and 74 | 2176 |

| 76 | limit 75 to embase | 1816 |

CINAHL, EBSCOHost

| # | Query | Results |

| S97 | S90 OR S91 OR S92 OR S93 OR S94 OR S95 [Exclude MEDLINE records] | 329 |

| S96 | S90 OR S91 OR S92 OR S93 OR S94 OR S95 | 1,391 |

| S95 | S74 and S89 | 108 |

| S94 | S70 and S89 | 83 |

| S93 | S16 and S65 and S89 | 390 |

| S92 | S39 and S57 and S89 | 224 |

| S91 | S29 and S49 and S89 | 230 |

| S90 | S16 and S29 and S39 and S89 | 935 |

| S89 | S75 or S76 or S77 or S78 or S79 or S80 or S81 or S82 or S83 or S84 or S85 or s86 or S87 or S88 | 1,105,239 |

| S88 | TI (effect* or impact* or intervention* or before N5 after or pre N5 post or ((pretest or "pre test") and (posttest or "post test")) or quasiexperiment* or quasi W0 experiment* or evaluat* or "time series" or time W0 point* or repeated W0 measur*) OR AB (before N5 after or pre N5 post or ((pretest or "pre test") and (posttest or "post test")) or quasiexperiment* or quasi W0 experiment* or evaluat* or "time series" or time W0 point* or repeated W0 measur*) | 411,775 |

| S87 | TI ( randomis* or randomiz* or randomly) OR AB ( randomis* or randomiz* or randomly) | 101,250 |

| S86 | (MH "Health Services Research") | 6,930 |

| S85 | (MH "Multicenter Studies") | 8,926 |

| S84 | (MH "Quasi‐Experimental Studies+") | 7,802 |

| S83 | (MH "Pretest‐Posttest Design+") | 24,583 |

| S82 | (MH "Experimental Studies") | 13,976 |

| S81 | (MH "Nonrandomized Trials") | 157 |

| S80 | (MH "Intervention Trials") | 5,536 |

| S79 | (MH "Clinical Trials") | 81,250 |

| S78 | (MH "Randomized Controlled Trials") | 21,621 |

| S77 | PT research | 937,077 |

| S76 | PT clinical trial | 51,827 |

| S75 | PT randomized controlled trial | 26,075 |

| S74 | S71 or S72 or S73 | 158 |

| S73 | TI control W1 diarrhea* W1 disease* or AB control W1 diarrhea* W1 disease* | 1 |

| S72 | TI neonatal W1 resuscitation W1 program* or AB neonatal W1 resuscitation W1 program* | 80 |

| S71 | TI integrated W1 management W1 childhood W1 Illness* or AB integrated W1 management W1 childhood W1 Illness* | 77 |

| S70 | S66 or S67 or S68 or S69 | 256 |

| S69 | (MH "Pediatric Advanced Life Support/ED") | 44 |

| S68 | (MH "Pediatric Critical Care Nursing+/ED") | 145 |

| S67 | (MH "Intensive Care Units, Pediatric+/ED") | 13 |

| S66 | (MH "Intensive Care, Neonatal+/ED") | 61 |

| S65 | S58 or S59 or S60 or S61 or S62 or S63 or S64 | 29,360 |

| S64 | TI ( "acute respiratory infection*" or "acute respiratory syndrome" or sars ) or AB ( "acute respiratory infection*" or "acute respiratory syndrome" or sars ) | 1,756 |

| S63 | (MH "Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome") | 1,491 |

| S62 | (MH "Infant, Newborn, Diseases+") | 15,314 |

| S61 | (MH "Pediatric Advanced Life Support") | 186 |

| S60 | (MH "Pediatric Critical Care Nursing+") | 3,286 |

| S59 | (MH "Intensive Care Units, Pediatric+") | 8,776 |

| S58 | (MH "Intensive Care, Neonatal+") | 3,412 |

| S57 | S50 or S51 or S52 or S53 or S54 or S55 or S56 | 3,500 |

| S56 | (MH "Emergency Nursing+/ED") | 582 |

| S55 | (MH "Resuscitation+/ED") | 1,326 |

| S54 | (MH "First Aid/ED") | 224 |

| S53 | (MH "Education, Emergency Medical Services") | 874 |

| S52 | (MH "Emergency Medical Services+/ED") | 353 |

| S51 | (MH "Life Support Care/ED") | 33 |

| S50 | (MH "Critical Care+/ED") | 228 |

| S49 | S40 or S41 or S42 or S43 or S44 or S45 or S46 or S47 or S48 | 2,735 |

| S48 | (MH "Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome/ED") | 15 |

| S47 | (MH "Infant, Newborn, Diseases+/ED") | 55 |

| S46 | (MH "Pediatric Nursing+/ED") | 1,124 |

| S45 | (MH "Pediatric Care+/ED") | 242 |

| S44 | (MH "Prenatal Care/ED") | 61 |

| S43 | (MH "Perinatal Care/ED") | 50 |

| S42 | (MH "Pediatrics+/ED") | 868 |

| S41 | (MH "Child Health/ED") | 48 |

| S40 | (MH "Child Care+/ED") | 302 |

| S39 | S30 or S31 or S32 or S33 or S34 or S35 or S36 or S37 or S38 | 396,979 |

| S38 | TI ( child* or infant* or pediatric* or paediatric* or perinat* or newborn* or new W0 born* or neonat* or baby or babies or kid or kids or toddler* ) or AB ( child* or infant* or pediatric* or paediatric* or perinat* or newborn or new W0 born* or neonat* or baby or babies or kid or kids or toddler* ) | 268,672 |

| S37 | (MH "Pediatric Nursing+") | 15,707 |

| S36 | (MH "Pediatric Care+") | 8,942 |

| S35 | (MH "Prenatal Care") | 8,159 |

| S34 | (MH "Perinatal Care") | 1,887 |

| S33 | (MH "Pediatrics+") | 7,689 |

| S32 | (MH "Child Health") | 9,312 |

| S31 | (MH "Child Care+") | 6,214 |

| S30 | (MH "Child+") | 305,018 |

| S29 | S17 or S18 or S19 or S20 or S21 or S22 or S23 or S24 or S25 or S26 or S27 or S28 | 201,390 |

| S28 | TI ( "case management" or emergency or "life support" or resuscitation or "first aid" or referral N2 care or urgent N2 care or critical* N2 care or critical* N2 ill or critical* N2 illness or critical* N2 treatment or critical* N2 therap* or intensive N2 care or intensive N2 ill or intensive N2 illness or intensive N2 treatment or intensive N2 therap* or serious* N2 care or serious* N2 ill or serious* N2 illness or serious* N2 treatment or serious* N2 therap* or sever* N2 care or sever* N2 ill or sever* N2 illness or sever* N2 treatment or sever* N2 therap* or acute* N2 care or acute* N2 ill or acute* N2 illness or acute* N2 treatment or acute* N2 therap* or "trauma nursing" ) or AB ( "case management" or emergency or "life support" or resuscitation or "first aid" or referral N2 care or urgent N2 care or critical* N2 care or critical* N2 ill or critical* N2 illness or critical* N2 treatment or critical* N2 therap* or intensive N2 care or intensive N2 ill or intensive N2 illness or intensive N2 treatment or intensive N2 therap* or serious* N2 care or serious* N2 ill or serious* N2 illness or serious* N2 treatment or serious* N2 therap* or sever* N2 care or sever* N2 ill or sever* N2 illness or sever* N2 treatment or sever* N2 therap* or acute* N2 care or acute* N2 ill or acute* N2 illness or acute* N2 treatment or acute* N2 therap* or "trauma nursing" ) | 128,460 |

| S27 | (MH "Emergency Nursing+") | 11,165 |

| S26 | (MH "Resuscitation+") | 21,788 |

| S25 | (MH "First Aid") | 1,505 |

| S24 | (MH "Emergency Medicine") | 5,367 |

| S23 | (MH "Emergency Medical Services+") | 54,380 |

| S22 | (MH "Catastrophic Illness") | 269 |

| S21 | (MH "Acute Disease") | 11,446 |

| S20 | (MH "Critical Illness") | 4,448 |

| S19 | (MH "Life Support Care") | 1,578 |

| S18 | (MH "Critical Care+") | 13,895 |

| S17 | (MH "Case Management") | 11,630 |

| S16 | S1 or S2 or S3 or S4 or S5 or S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 or S14 or S15 | 65,588 |

| S15 | TI ( "life support" N2 train* or "life support" N2 course or "life support" N2 development or "life support" N2 education or "life support" N2 teach* or "job training" ) or AB ( "life support" N2 train* or "life support" N2 course or "life support" N2 development or "life support" N2 education or "life support" N2 teach* or "job training" ) | 531 |

| S14 | TI ( inservice N2 train* or inservice N2 course or inservice N2 development or inservice N2 education or inservice N2 teach* or "in service" N2 train* or "in service" N2 course or "in service" N2 development or "in service" N2 education or "in service" N2 teach* ) or AB ( inservice N2 train* or inservice N2 course or inservice N2 development or inservice N2 education or inservice N2 teach* or "in service" N2 train* or "in service" N2 course or "in service" N2 development or "in service" N2 education or "in service" N2 teach* ) | 994 |

| S13 | TI ( dieti?ian* N2 train* or dieti?ian* N2 course or dieti?ian* N2 development or dieti?ian* N2 education or dieti?ian* N2 teach* or nutritionist* N2 train* or nutritionist* N2 course or nutritionist* N2 development or nutritionist* N2 education or nutritionist* N2 teach* ) or AB ( dieti?ian* N2 train* or dieti?ian* N2 course or dieti?ian* N2 development or dieti?ian* N2 education or dieti?ian* N2 teach* or nutritionist* N2 train* or nutritionist* N2 course or nutritionist* N2 development or nutritionist* N2 education or nutritionist* N2 teach* ) | 156 |

| S12 | TI ( practitioner* N2 train* or practitioner* N2 course or practitioner* N2 development or practitioner* N2 education or practitioner* N2 teach* ) or AB ( practitioner* N2 train* or practitioner* N2 course or practitioner* N2 development or practitioner* N2 education or practitioner* N2 teach* ) | 1,842 |

| S11 | TI ( specialist* N2 train* or specialist* N2 course or specialist* N2 development or specialist* N2 education or specialist* N2 teach* ) or AB ( specialist* N2 train* or specialist* N2 course or specialist* N2 development or specialist* N2 education or specialist* N2 teach* ) | 1,126 |

| S10 | TI ( pharmacist* N2 train* or pharmacist* N2 course or pharmacist* N2 development or pharmacist* N2 education or pharmacist* N2 teach* ) or AB ( pharmacist* N2 train* or pharmacist* N2 course or pharmacist* N2 development or pharmacist* N2 education or pharmacist* N2 teach* ) | 237 |

| S9 | TI ( midwif* N2 train* or midwif* N2 course or midwif* N2 development or midwif* N2 education or midwif* N2 teach* or midwives N2 train* or midwives N2 course or midwives N2 development or midwives N2 education or midwives N2 teach* ) or AB ( midwif* N2 train* or midwif* N2 course or midwif* N2 development or midwif* N2 education or midwif* N2 teach* or midwives N2 train* or midwives N2 course or midwives N2 development or midwives N2 education or midwives N2 teach* ) | 1,549 |

| S8 | TI ( nurse* N2 train* or nurse* N2 course or nurse* N2 development or nurse* N2 education or nurse* N2 teach* ) or AB ( nurse* N2 train* or nurse* N2 course or nurse* N2 development or nurse* N2 education or nurse* N2 teach* ) | 13,757 |

| S7 | TI ( physician* N2 train* or physician* N2 course or physician* N2 development or physician* N2 education or physician* N2 teach* ) or AB ( physician* N2 train* or physician* N2 course or physician* N2 development or physician* N2 education or physician* N2 teach* ) | 2,544 |

| S6 | TI ( clinician* N2 train* or clinician* N2 course or clinician* N2 development or clinician* N2 education or clinician* N2 teach* ) or AB ( clinician* N2 train* or clinician* N2 course or clinician* N2 development or clinician* N2 education or clinician* N2 teach* ) | 1,025 |

| S5 | TI ( employee* N2 train* or employee* N2 course or employee* N2 development or employee* N2 education or employee* N2 teach* ) or AB ( employee* N2 train* or employee* N2 course or employee* N2 development or employee* N2 education or employee* N2 teach* ) | 434 |

| S4 | TI ( staff N2 train* or staff N2 course or staff N2 development or staff N2 education or staff N2 teach* ) or AB ( staff N2 train* or staff N2 course or staff N2 development or staff N2 education or staff N2 teach* ) | 6,579 |

| S3 | (MH "Internship and Residency") | 6,452 |

| S2 | (MH "Health Personnel+/ED") | 19,663 |

| S1 | (MH "Staff Development") | 19,164 |

ERIC, ProQuest

ALL(inservice P/2 education or "in service" P/2 education or inservice P/2 training or "in service" P/2 training or "on the job training" or "on the job education" or inservice P/2 course* or "in service" P/2 course* or inservice P/2 workshop* or "in service" P/2 workshop* or inservice P/2 program* or "in service" P/2 program*) and ALL("crisis management" or crisis P/0 intervention* or acute P/2 care or acute* P/2 treatment* or acute* P/2 therap* or emergency P/2 care or emergency P/2 treatment* or emergency P/2 therap* or emergency P/2 program* or intensive P/2 care or intensive P/2 treatment* or intensive P/2 therap*or critical P/2 care or critical P/2 treatment* or critical P/2 therap* or urgent P/2 care or urgent P/2 treatment or "first aid" or "life support" or resuscitation or acute* P/0 ill* or emergency P/0 ill* or critical* P/0 ill* or serious* P/0 ill* or sever* P/0 ill*) and ALL(child or children or infant or infants or pediatric* or paediatric* or newborn* or new P/0 born* or neonat* or perinat* baby or babies or kid or kids or toddler)

WHOLIS, WHO

Words or phrase: inservice or job

AND

Words or phrase: training or education or course$ or workshop$ or program$

AND

Words or phrase: child$ or infant$ or pediatric$ or paediatric$ or newborn$ or new born or neonat$ or perinat$ or baby or babies or kid or kids or toddler$

LILACS, VHL (IAH interface)

(inservice and training) or (inservice and course$) or (inservice and workshop$) or (inservice and education) or (inservice and program$) or (capacitación and servicio) or (capacitação and serviço) [Words]

And

child or children or niño or criança or infant or infants or lactante or lactente or pediatric$ or paediatric$ or pediatría or pediatria or newborn or (recién and nacidos) or (recém and nascidos) or neonat$ or baby or babies or kid or kids or toddler$ [Words]

Science Citation Index and Social Sciences Citation Index (ISI Web of Science)

Citation search for two included studies:

1. Opiyo N, Were F, Govedi F, Fegan G, Wasunna A, English M. Effect of newborn resuscitation training on health worker practices in Pumwani Hospital, Kenya. PLoS ONE 2008;13;3(2):e1599.

2. Senarath U, Fernando DN, Rodrigo I. Effect of training for care providers on practice of essential newborn care in hospitals in Sri Lanka. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing 2007;36(6):531‐41.

Appendix 2. GRADE evidence profile

|

In‐service neonatal emergency care training versus usual care for healthcare professionals Participants: nurses and midwives Settings: delivery room/theatre (Kenya) Intervention: 1‐day newborn resuscitation training Comparison: usual care | |||||||||||||

| Quality assessment | Number of practices | Effect | Quality | Importance | |||||||||

| Number of studies | Design | Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | With in‐service training | Usual care | Relative (95% CI) | Absolute | |||

| Health workers' resuscitation practices (proportion of adequate initial resuscitation steps; follow‐up 50 days; assessed with direct observation) | |||||||||||||

| 1 | Randomised trial | Serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 64/97 (66%) | 31/115 (27%) | RR 2.45 (1.75 to 3.42) |

39 more per 100 (from 20 more to 65 more) | ⊕⊕⊕Οa Moderate | CRITICAL | |

| Health workers' resuscitation practices (inappropriate and potentially harmful practices per resuscitation; follow‐up 50 days; measured with direct observation; better indicated by lower values) | |||||||||||||

| 1 | Randomised trial | Serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | No serious imprecision | None | 97 | 115 | ‐ | MD 0.39 higher (0.13 to 0.66 higher) | ⊕⊕⊕Οa Moderate | CRITICAL | |

| Neonatal mortality in all resuscitation episodes (follow‐up 50 days; assessed with medical records ‐ resuscitation observation sheets) | |||||||||||||

| 1 | Randomised trial | Serious1 | No serious inconsistency | No serious indirectness | Serious2 | None | 18/65 (27.7%) | 9/25 (36%) | RR 0.77 (0.40 to 1.48) |

8 fewer per 100 (from 22 fewer to 17 more) | ⊕⊕ΟΟa,b Low | CRITICAL | |