Abstract

Patient: Male, 50

Final Diagnosis: Adrenal pseudocys

Symptoms: Abdominal pain • fever

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: —

Objective:

Unusual clinical course

Background:

Most abdominal cysts, including adrenal pseudocysts, are benign and asymptomatic. Rapid enlargement, hemorrhage, infection, rupture with leakage of cyst contents, or pressure on adjacent organs can cause symptoms. Although usually diagnosed incidentally on imaging, determining the origin of a cyst can sometimes be challenging. In these situations, surgical excision and pathological analysis is crucial to diagnosis and management. We report here a case of a giant symptomatic adrenal pseudocyst that closely mimicked a hepatic cyst at presentation.

Case Report:

A 50-year-old man, with a history of an incidentally detected hepatic cyst, presented with severe abdominal pain, fevers, leukocytosis, and mildly abnormal liver function tests. CT scan revealed a large well defined cystic space-occupying lesion within the liver, with findings suggesting cyst rupture and possible infection. Early laparotomy was performed, and the origin was determined intraoperatively to be right adrenal, which was later confirmed by pathology.

Conclusions:

Contrast-enhanced CT scan is the criterion standard for evaluation for abdominal cystic masses. Precise diagnosis of a giant abdominal cyst can be challenging. Surgery is both diagnostic and curative in such situations. We also discuss the specific situations in which surgery should be considered in cases of adrenal cystic masses.

MeSH Keywords: Abdomen, Acute; Adrenal Gland Neoplasms; Adrenal Glands; Liver Diseases

Background

Most abdominal cystic masses are benign. Determining the origin of a cyst preoperatively can sometimes be challenging. A large right-sided adrenal cystic mass can rarely be mistaken for a hepatic cyst by imaging.

We report here a case of a giant symptomatic adrenal pseudocyst that closely mimicked a hepatic cyst. It was intraoperatively determined to be of adrenal origin. After successful excision, it was confirmed to be an adrenal pseudocyst by pathology.

Case Report

A 50-year-old African-American man presented with severe intermittent right upper-quadrant abdominal pain, nausea, and fever episodes for 4 days. His medical history was significant for an incidental hepatic cyst detected by computerized tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen 2 years ago at another hospital, at which time he was asymptomatic.

On clinical examination, the patient’s temperature was 39.6°C, blood pressure was 112/66 mm Hg, and heart rate was 110 beats per minute. Abdominal examination demonstrated a soft abdomen but was significant for diffuse tenderness. There was also tender hepatomegaly extending 15 cm below the right costal margin. There was no guarding, rigidity, or rebound tenderness. Laboratory investigation revealed a total leukocyte count of 16 800/mm3 with 80% neutrophils. Liver function tests revealed a mild hyperbilirubinemia with a total bilirubin of 3.3 mg/dl, direct bilirubin of 2.3 mg/dl, alkaline phosphatase of 135 U/L, and normal transaminases. Serum amylase, lipase, and basic metabolic profile were within normal limits. Urinalysis, chest X-ray, and electrocardiogram were within normal limits.

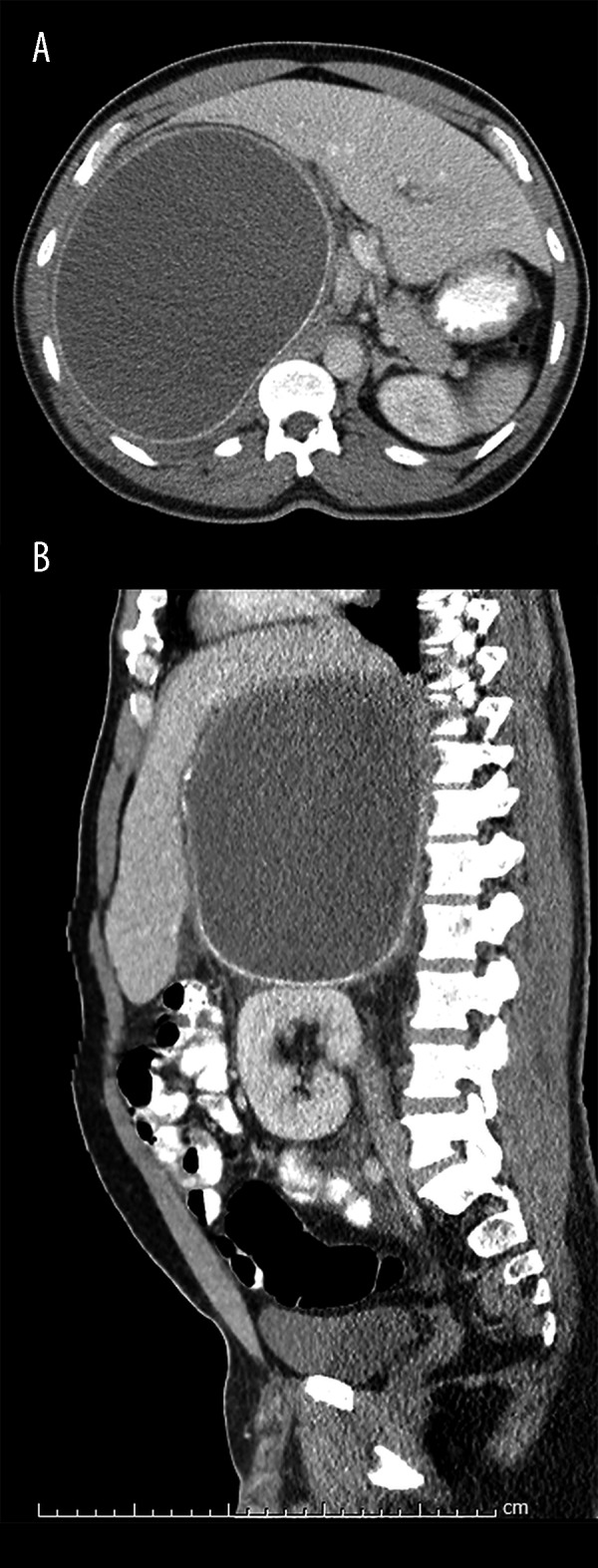

A prior CT scan from 3 months earlier had revealed a 21×18×15 cm rim-calcified cyst in the right hemi-abdomen, exerting mass effect on the liver and inferiorly displacing the right kidney. No plane of separation was visible between the cyst and either the right lobe of the liver or the right kidney. However, because the liver appeared to wrap around the cyst and only a small portion of the right kidney abutted the cyst, a hepatic origin was favored. While the appearance was not typical of an echinococcal cyst, this is not entirely excluded (Figures 1, 2). A 9-mm cystic hypodensity in the head of the pancreas was noted, likely representing a cystic pancreatic neoplasm, such as a side-branch intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN). Nonspecific, mildly enlarged, mesenteric lymph nodes were also seen.

Figure 1.

A large cystic mass seen in the RUQ on a prior CT abdomen: coronal view of the cyst exerting mass effect on the liver and inferiorly displacing the right kidney.

Figure 2.

CT abdomen 3 months prior to presentation: giant 21×18×15 cm, Rimmed, calcified cyst in the right hemi-abdomen.

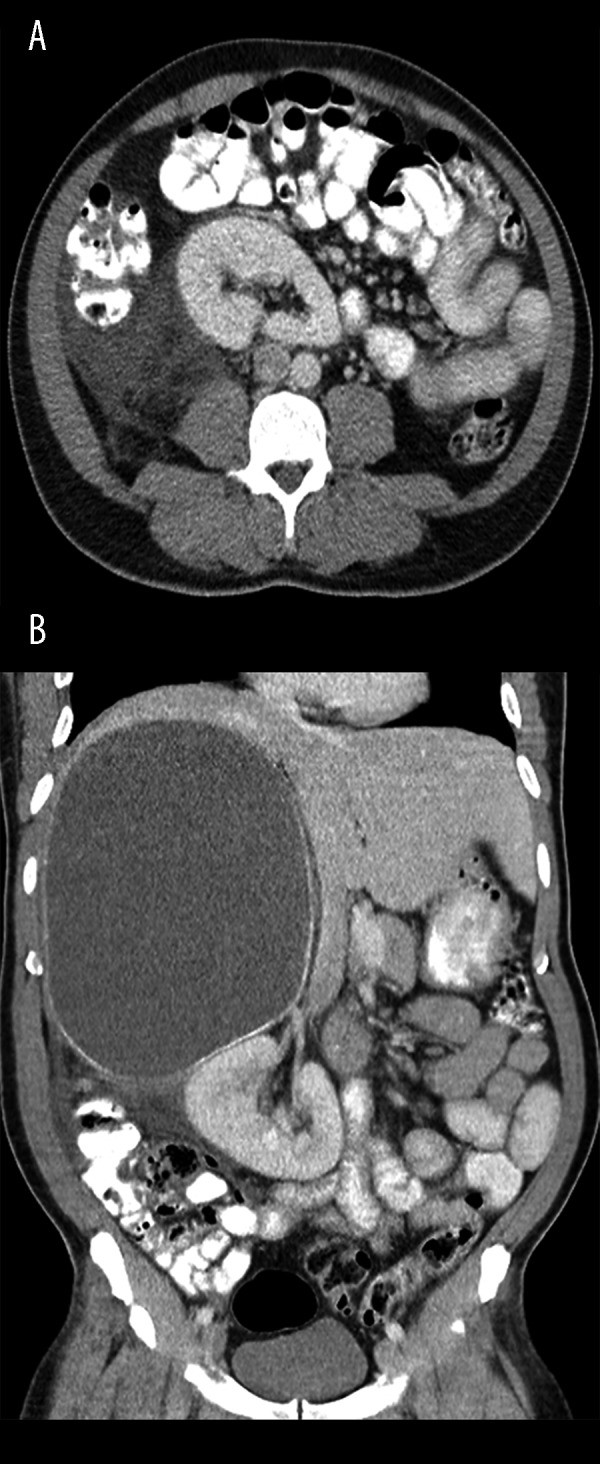

A repeat CT scan was performed on admission, which showed a large, well defined, cystic space-occupying lesion measuring 21×18×14 cm in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen with inferior-medial displacement of the right kidney and mass effect on the right lobe of the liver (Figure 3A, 3B). The interior of the cyst measured higher density than water (22 Hounsfield Units). There was stranding in the adjacent mesenteric fat, with fluid surrounding the cyst and extending into the right pararenal and retrocolic space, suggesting a retroperitoneal location of the cyst. A small hypodensity was again noted in the pancreas with sub-centimeter nodes in the mesentery (Figure 4A, 4B).

Figure 3.

(A, B) CT abdomen obtained this admission in axial and sagittal views showing cystic mass in RUQ.

Figure 4.

(A, B) Axial and coronal views. Fluid and stranding in the pararenal and retrocolic space inferior to the cyst are apparent.

These findings suggested rupture of the cyst with possibility of infection, and an early laparotomy was performed after starting the patient on appropriate antibiotics. A large cyst adherent to the surrounding right-sided abdominal structures was found. After meticulous dissection, the cyst was separated from all the surrounding abdominal structures, except on the posterior aspect due to adhesions to the kidney. The cyst was then decompressed by draining 2 liters of foul-smelling hemorrhagic material. The posterior adhesions were excised to deliver the cyst. The origin of the cyst was ascertained intraoperatively to be the right adrenal gland.

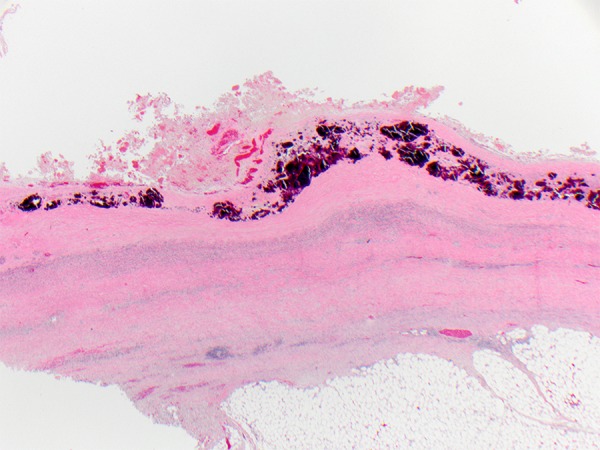

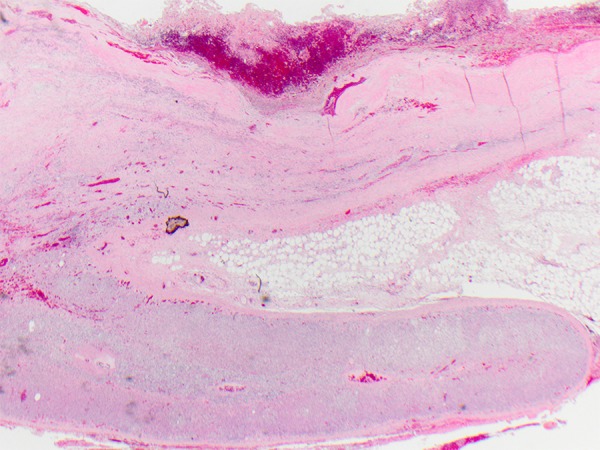

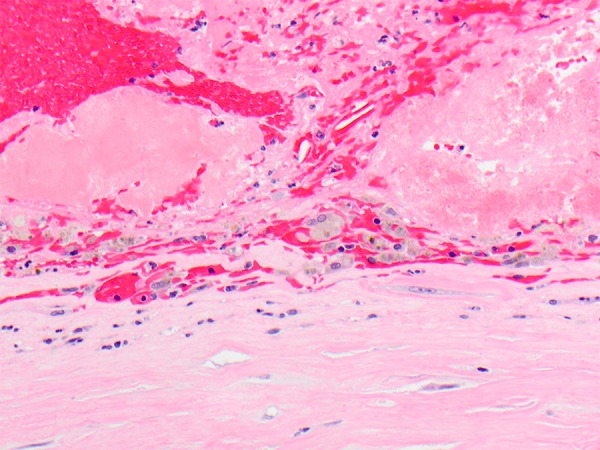

Pathological analysis of the excised cyst and right adrenal gland was performed. It was confirmed as an adrenal pseudocyst of 18-cm size with mural calcifications (Figures 5, 6). No epithelial lining was found (Figure 7). There was acute inflammation and hemorrhage in the lumen. No scolices or hook-lets consistent with Echinococcus spp. were identified on polarization microscopy. The cyst wall contained adrenal cortical tissue, confirmed by A103 (Melan-A) immunohistochemistry, thereby making this an adrenal cyst. A post-surgical CT scan revealed a seroma in the retroperitoneum and fat stranding in the right hypochondrium, with peritoneal thickening suggestive of post-surgical changes. The apparent “hepatomegaly” and the mild abnormalities in the liver function tests resolved completely after the surgery.

Figure 5.

Cyst wall with heavy mural calcifications.

Figure 6.

Cyst wall contiguous with adrenal tissue (2×).

Figure 7.

Pseudocyst wall on 40× magnification. No epithelial lining is present.

Discussion

Adrenal cysts are often discovered incidentally, and the reported incidence is increasing due to increased detection rates from more liberal use of imaging in the present era [1]. The incidence is reported as 0.064% in surgical series and 0.18% on autopsies [2]. They account for 5% of incidentally detected adrenal lesions [3]. Approximately 80% of these cystic lesions of the adrenal gland are pseudocysts [4,5]. Adrenal pseudocysts are rare, benign, non-functional cystic masses arising from the cortex or medulla and are usually asymptomatic. Symptoms can develop, particularly in the case of large cysts (>10 cm), due to pressure exerted on adjacent organs, if the cyst is rapidly enlarging, or if complicated by hemorrhage, infection, or rupture with leakage of the cyst contents [6,7].

Unlike true cysts, pseudocysts have no definite endothelial or epithelial cellular lining. Adrenal pseudocysts are microscopically composed of fibrous tissue, sometimes with calcification. The lumen contains blood, and attenuated adrenal gland tissue is often present in the wall. The pathogenesis of an adrenal pseudocyst is unclear. Possible etiologies include vascular origin, neoplastic growth, adrenal parenchymal malformation, or hemorrhage into the adrenal parenchyma [8].

Evaluation of adrenal cysts can be done using imaging with ultrasound (US), CT scan, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), but contrast-enhanced CT scan is the criterion standard. On CT and MRI, a pseudocyst may have a homogenous cystic appearance (low attenuation on CT or hypo-intense on T1-weighted and hyper-intense on T2-weighted images). Complex pseudocysts may appear more heterogeneous due to septations, blood products, and calcifications. The adjacent tissue involvement and the mass effects can be well depicted on both CT and MRI. Careful hormonal, morphological, functional, and instrumental evaluation is indicated in all adrenal cysts [9].

Adrenal cysts may occasionally mimic hepatic cysts, as in our case, particularly if the organ of origin cannot be clearly identified on imaging. In our case, the mass was extensive, and appeared to originate from the liver. The high attenuation value on CT, with surrounding inflammatory changes and fluid in the retroperitoneum, were indicative of a complicated cyst, warranting immediate surgical intervention.

Differential diagnoses of adrenal pseudocysts include true adrenal cysts, lymphangiomas, pseudocysts of pancreatic origin, dermoids, cystic adrenal carcinomas, and, rarely, hydatid cysts of the adrenal glands. Nevertheless, there are some characteristics that may help differentiate these entities. A hydatid cyst is a low-density fluid-attenuation mass with or without septations, most commonly found in the liver. The hydatid cyst wall and septae may enhance. A pancreatic pseudocyst would be associated with other features of pancreatitis. Lymphangioma is suggested by a water- or fat-containing cystic mass with septations and multiple locules. Other differentials of adrenal pseudocysts include splenic, hepatic, renal cysts, mesenteric, or retroperitoneal cysts, urachal cysts, and even solid adrenal tumors.

Surgical excision of adrenal pseudocysts, preferably by laparoscopic approach when possible, is indicated if the lesion is large (>5 cm) or in the presence of symptoms or endocrine abnormalities (even when subclinical), if there are clinical complications, or if there is a suspicion of malignancy [9].

Conclusions

An adrenal pseudocyst can present as a large cyst incidentally or with subacute symptoms like recurrent intermittent abdominal pain, or as an acute abdomen when complications such as rupture and infection occur. Precise diagnosis of a giant cyst in the abdomen can be challenging. Surgery is both diagnostic and curative in such situations.

Footnotes

Disclosures of conflict of interest

None.

References:

- 1.Wang LS, Wong YC, Chan CJ, et al. Imaging Spectrum of adrenal pseudocyst on CT. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:531–35. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1537-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rozenblit a Morehouse HT, Amis ES., Jr Cystic adrenal lesions; CT features. Radiology. 1996;201(Suppl.2):541–48. doi: 10.1148/radiology.201.2.8888255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masumori N, Adachi H, Noda Y, Tsukamoto T. Detection of adrenal and retroperitoneal masses in a general health examination system. Urology. 1998;52(Suppl.4):572–76. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erickson LA, Lloyd RV, Hartman R, Thompson G. Cystic adrenal neoplasms. Cancer. 2004;101:1537–44. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellantone R, Ferrante A, Raffaelli M, et al. Adrenal cystic lesions: report of 12 surgically treated cases and review of the literature. J Endocrinol Invest. 1998;21:109–14. doi: 10.1007/BF03350324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papaziogas B, Katsikas B, Psaralexis K, et al. Adrenal pseudocyst presenting as acute abdomen during pregnancy. Acta Chir Belg. 2006;106:722–25. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2006.11679993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tagge DU, Baron PL. Giant adrenal cyst: management and review of literature. Am Surg. 1997;63(8):744–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medeiros LJ, Lewandrowsui KB, Vickery AL. Adrenal pseudocyst: a clinical and pathological study of 8. Human Pathology. 1989;20:660–65. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(89)90153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellantone R, Ferrante A, Raffaelli M, et al. Adrenal cystic lesions: report of 12 surgically treated cases and review of the literature. J Endocrinol Inves. 1998;21(2):109–14. doi: 10.1007/BF03350324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]