Abstract

Purpose

The aim of the study was to develop a European list of potentially inappropriate medications (PIM) for older people, which can be used for the analysis and comparison of prescribing patterns across European countries and for clinical practice.

Methods

A preliminary PIM list was developed, based on the German PRISCUS list of potentially inappropriate medications and other PIM lists from the USA, Canada and France. Thirty experts on geriatric prescribing from Estonia, Finland, France, the Netherlands, Spain and Sweden participated; eight experts performed a structured expansion of the list, suggesting further medications; twenty-seven experts participated in a two-round Delphi survey assessing the appropriateness of drugs and suggesting dose adjustments and therapeutic alternatives. Finally, twelve experts completed a brief final survey to decide upon issues requiring further consensus.

Results

Experts reached a consensus that 282 chemical substances or drug classes from 34 therapeutic groups are PIM for older people; some PIM are restricted to a certain dose or duration of use. The PIM list contains suggestions for dose adjustments and therapeutic alternatives.

Conclusions

The European Union (EU)(7)-PIM list is a screening tool, developed with participation of experts from seven European countries, that allows identification and comparison of PIM prescribing patterns for older people across European countries. It can also be used as a guide in clinical practice, although it does not substitute the decision-making process of individualised prescribing for older people. Further research is needed to investigate the feasibility and applicability and, finally, the clinical benefits of the newly developed list.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00228-015-1860-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Potentially inappropriate medication, Inappropriate prescribing [MeSH term], Aged [MeSH term], Screening, Europe [MeSH term]

Background

Appropriate prescribing for older people is a public health concern, and several assessment tools are available for its evaluation. Most of the tools focus on pharmacological appropriateness of prescribing [1]; they address various aspects of appropriateness, including overprescribing of medications that are clinically not indicated, omission of medications that are needed, and incorrect prescriptions of medications that may be indicated [2]. The term “potentially inappropriate medications (PIM) for older people” has been used to refer to those drugs which should not be prescribed for this population because the risk of adverse events outweighs the clinical benefit, particularly when there is evidence in favour of a safer or more effective alternative therapy for the same condition [3, 4].

The prevalence of inappropriate prescribing and/or use of PIM has been analysed by several authors and ranges from 20 to 79 % depending on the population studied, the setting or country, and the specific tool used [5–10]. Inappropriate prescribing and use of PIM can be associated with adverse outcomes such as adverse drug events [11–13], hospitalisation [6, 14] and death [15].

A recently published systematic review identified 46 tools or criteria for assessing inappropriate prescribing [16]. A prior systematic review identified 14 criteria specific for individuals aged 65 and older [1]. Generally, the assessment tools have been developed based on expert opinion due to the lack of high-quality studies on the use of drugs in older people [17], although some tools have additionally used a literature search [18, 19]. Criteria have been classified into explicit or implicit or mixed approach [1]. Explicit criteria are generally lists of medications or criteria which can be applied with little or no clinical judgement but do not address individual differences between patients [2]. Implicit criteria are based on the judgement of a professional and are person-specific [20], requiring individual patient data for application, however, they are time-consuming and more dependent on the user [2]. No single ideal tool has been identified so far, but each tool seems to have its strengths and weaknesses, and the choice of a tool may depend on the purpose of use (i.e. daily practice, research) and availability of data [16].

Assessment tools are being used increasingly for the evaluation of prescribing quality in older people, but their application cannot substitute the individual assessment of prescribing appropriateness [16]. One of the limitations of the tools is the fact that the majority was developed following country-specific guidelines, national drug markets and prescribing habits, hence, limiting their transferability to other countries [1, 21]. For instance, the German PRISCUS list of potentially inappropriate medications, a purely explicit list, defines 83 PIM drugs, of which twelve are not on the drug market in France, the USA and Canada. However, there are 124 drugs on the PIM lists of these countries which are not part of the German PRISCUS list, because seventy of them are not on the German drug market and many others are almost never used [22]. To the best of our knowledge, no assessment tool covers the drug markets of several European countries and could thus enable the analysis of European databases.

The present study was conceived when planning to analyse the prescription of PIM among a European cohort of older people with dementia participating in the RightTimePlaceCare study [23]. The primary aim of our study was to develop an expert-consensus list of potentially inappropriate medications covering the drug markets of seven European countries, which can be used for the analysis of potentially inappropriate prescription patterns in and across several European countries. Additionally, the list should be applicable in clinical practice to alert health care professionals to the likelihood of inappropriate prescribing, possible dose adjustments required and therapeutic alternatives.

Methods

A research team consisting of a clinical pharmacologist, a pharmacist, a nursing scientist and a geriatrician planned and coordinated the development of the European Union (EU)(7)-PIM list. Two members of the research team were developers of the German PRISCUS list [22]. The study comprised five consecutive phases:

Preparation of a preliminary PIM list. We prepared a preliminary PIM list which contained 85 PIM (82 active substances plus one combination of active substances and two different preparations of one substance) from the German PRISCUS list [22] and 99 PIM from the French [3], American [24, 25] and Canadian [26] lists. These tools have been used in research to evaluate the prescription of PIM and factors associated with PIM use [5, 6, 14, 27–29]. The main reason for each drug being PIM was formulated using the information provided by the original lists. This process was supported by a comprehensive literature search. The anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) code classification system was used (2011) [30].

Recruitment of experts on geriatric prescribing/pharmacotherapy. We established a collaboration with the Seventh Framework European project RightTimePlaceCare [23], a project aiming to develop best practice recommendations for dementia care throughout Europe. The consortium partners of this project supported the recruitment of experts on geriatric prescribing or pharmacotherapy in their respective countries. Thirty-three experts from six European countries agreed to participate; they came from Finland (n = 3), Estonia (n = 9), the Netherlands (n = 4), France (n = 2), Spain (n = 7) and Sweden (n = 8). The following professions were represented as follows: geriatricians (n = 14), pharmacists (n = 3), clinical pharmacologists (n = 7) and other medical specialists (n = 9). Experts were sent information documents describing the aims, concepts and steps of the study and were asked whether they preferred to participate in the expansion phase (phase 3), in the Delphi survey (phase 4), or in both.

Expansion of the preliminary PIM list. We asked thirteen experts representing the six countries to expand the preliminary PIM list by adding drugs that they considered should be PIM and which were not represented, paying special attention to those drugs available on their respective countries’ markets. Expansion of the preliminary list was Internet-based and concluded in May 2012.

-

Two-round Delphi survey. A two-round Delphi survey was performed [31]. The first Delphi round took place between October and December 2012, and the second Delphi round between March and May 2013. In the first round, we asked 29 experts to assess each drug of the preliminary expanded list for appropriateness by using a 1–5 points Likert scale where “1” represented “I strongly agree that the drug is potentially inappropriate for older people”; “2”, “I agree that the drug is potentially inappropriate for older people”; “3”, “average/neutral/undecided”; “4”, “I disagree that the drug is potentially inappropriate for older people”; “5”, “I strongly disagree that the drug is potentially inappropriate for older people”; and “0”, “no answer; I do not feel qualified to answer”. Experts were asked to provide suggestions for dose adjustments and safer therapeutic alternatives for those drugs judged as inappropriate. Experts were free to insert additional comments and were invited to expand the list with any further drugs they considered to be PIM.

In the second Delphi round, we asked 28 experts to assess the appropriateness of those drugs classified as questionable PIM during the first round (see “Expert agreement and statistics”), as well as the further suggestions for PIM made by the experts during the first Delphi round, and also eight drugs appearing in the recently published updated Beers list [18]. Some PIM concepts were adapted taking the experts’ suggestions made during the first Delphi round into account. The additional suggestions for PIM were given a justification as to why they may be classified as PIM, taking published data into consideration when necessary. Again, experts assessed the appropriateness of these drugs and were asked to provide dose adjustments, therapeutic alternatives, and to insert additional comments if necessary. Drugs were classified into PIM, non-PIM and questionable PIM (see “Expert agreement and statistics”).

Preparation of the final PIM list. Dose adjustments and drug alternatives suggested by the experts during the Delphi survey were compiled and included in the EU(7)-PIM list, prioritising in each case those made by the higher number of experts. Suggestions were complemented, if necessary, with information available from the other PIM lists and from Micromedex® [32], a commercially available database which contains comprehensive information on drug use. We identified those drugs for which some discussion issues raised by the experts still remained open and those drugs where inconsistency in the results was identified after checking the literature. In order to solve these problems, a reduced number of experts (n = 12) was invited to participate in the last brief survey which took place in September 2013.

Expert agreement and statistics

Several approaches have been suggested in the literature to define expert agreement within Delphi surveys [31]. In this study, after the first and second Delphi rounds, we calculated the means, the corresponding 95 % confidence intervals (CI) and the medians of all Likert scores given to each drug; expert agreement was considered if the CI of the mean score for each drug did not cross over the value 3. Thus, each drug was classified into PIM (if both the mean value of the score and the upper limit of the CI were lower than 3), non-PIM (if both the mean value of the score and the lower limit of the CI exceeded 3) and questionable PIM (if the CI was on both sides of the value 3). Statistical calculations were performed with SPSS, version 21.0.

Results

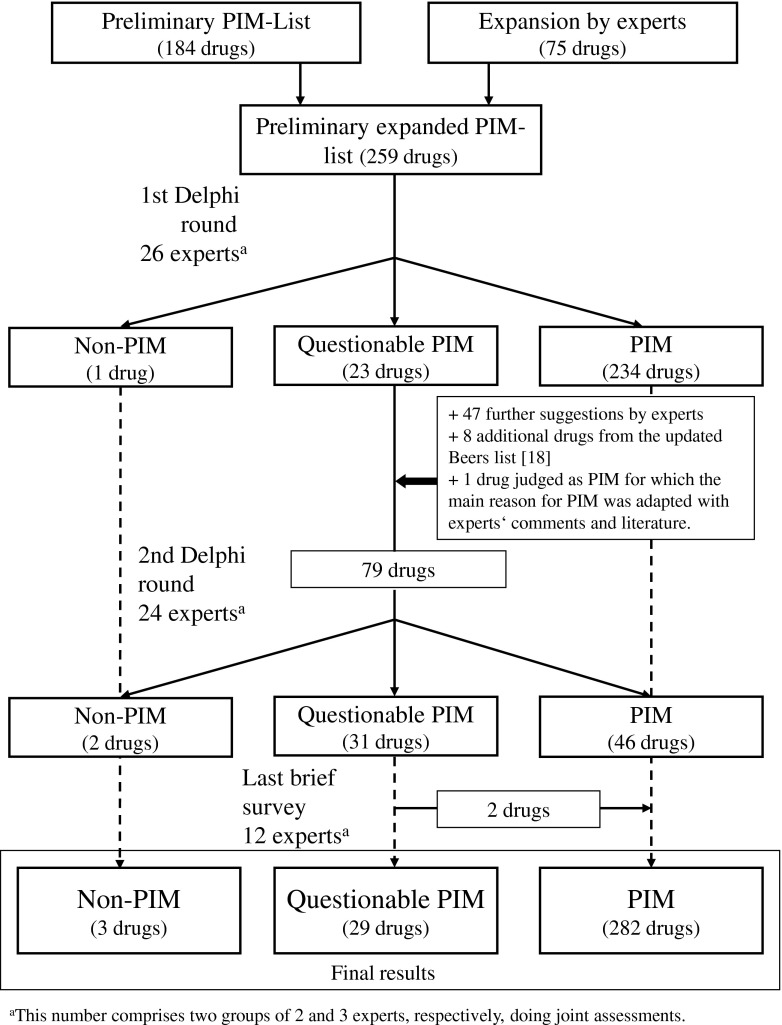

The preliminary PIM list contained 184 drugs (including two combinations of two drugs) and preparations (e.g. sustained-release preparations of oxybutynine). Eight of the 13 invited experts (62 %) participated in the expansion phase and suggested 75 additional drugs and preparations. Twenty-six out of the 29 invited experts (90 %) participated in the first Delphi round, and 24 out of the 28 invited experts (86 %) participated in the second Delphi round. Two experts from Spain and three experts from Finland chose to collaborate together in two teams to provide their assessments in both Delphi rounds. All the 12 experts invited participated in the last brief survey.

Figure 1 shows the development process of the list. In the first Delphi round, experts assessed 259 drugs and preparations, of which the majority (n = 234) were classified as PIM and only one drug as non-PIM. In the second Delphi round, experts assessed 79 drugs and preparations, comprising 23 questionable PIM, 47 further suggestions by experts, eight additional drugs from the updated Beers list [18] and one drug (naproxen) judged as PIM for which the main reason for PIM was adapted taking recent published data and experts’ comments into consideration. Again, 31 drugs and preparations remained as questionable PIM and 46 drugs were classified as PIM. Overall, after the third brief survey, 282 drugs and preparations were classified as PIM, 29 as questionable PIM and three as non-PIM.

Fig. 1.

The development process of the EU(7)-PIM list

The level of agreement between experts varied in the assessment of appropriateness. For example, experts reached consensus for diazepam being PIM with a mean Likert score of 1.61, confidence interval between 1.32 and 1.89, and median of 2. Consensus was reached also for digoxin being PIM (mean Likert score 2.19; confidence interval 1.57–2.81; median 2), but in this case, the Likert scores ranged from 1 to 5. No consensus was reached on the appropriateness of some drugs such as metamizole, which was classified as questionable PIM. For this drug, the disparity seemed to be in part due to the experts’ country of origin, since the majority of the Spanish experts considered metamizole to be appropriate when used in adequate doses, whereas the majority of Finnish experts considered this drug to be clearly inappropriate.

The last brief survey consisted of 11 questions with multiple-choice answers and covered issues regarding 13 drugs. The questions covered mostly dose-related issues commented by the experts during the survey which remained open (four drugs) and inconsistencies in the results identified after checking the literature (three drugs). Additionally, the research group asked the experts to provide their opinion on the use of three drugs. Finally, the research group did minimal corrections in the PIM which needed experts’ approval (three drugs). All of the issues could be solved.

Table 1 displays an abbreviated version of the EU(7)-PIM list, with the 72 PIM most frequently identified among the participants of the RightTimePlaceCare survey [23], a European cohort of older people with dementia (data not shown).

Table 1.

PIM according to the EU(7)-PIM lista

| PIM | Main reason | Dose adjustment/special considerations of use | Alternative drugs and/or therapies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drugs for peptic ulcer and gastro-oesophageal reflux | |||

| Ranitidine | CNS adverse effects including confusion | CrCl <50 mL/min 150 mg q 24h (oral); 50 mg q 18–24 h (iv). E | When indication is appropriate, PPI (<8 weeks, low dose). E |

| PPI (>8 weeks) e.g. omeprazole, pantoprazole | Long-term high dose PPI therapy is associated with an increased risk of C. difficile infection and hip fracture. Inappropriate if used >8 weeks in maximal dose without clear indication | ||

| Propulsives | |||

| Metoclopramide | Antidopaminergic and anticholinergic effects, may worsen peripheral arterial blood flow and precipitate intermittent claudication | Short-term use and dose reduction; CrCl <40 mL/min 50 % of normal dose; maximum dose 20 mg/d; may be used in palliative care. E | Domperidone (<30 mg/d) if no contraindications. E |

| Laxatives | |||

| Senna glycosides | Stimulant laxative. Adverse events include abdominal pain, fluid and electrolyte imbalance and hypoalbuminemia. May exacerbate bowel dysfunction | Recommend proper dietary fibre and fluid intake; osmotically active laxatives: macrogol, lactulose. E, P | |

| Sodium picosulfate | |||

| Antipropulsives | |||

| Loperamide (>2 days) | Risk of somnolence, constipation, nausea, abdominal pain and bloating. Rare adverse events include dizziness. May precipitate toxic megacolon in inflammatory bowel disease, may delay recovery in unrecognised gastroenteritis | Start with a dose of 4 mg followed by 2 mg in each deposition until normalisation of bowel; do not exceed 16 mg/d; use no longer than 2 days; may be useful in palliative care for persisting non-infectious diarrhoea. E | Non-pharmacological measures, e.g. diet; phloroglucinol. E |

| Insulins and analogues | |||

| Insulin, sliding scale | No benefits demonstrated in using sliding-scale insulin. Might facilitate fluctuations in glycemic levels | Lower doses to avoid hypoglycemia. E | Basal insulin. E |

| Blood glucose lowering drugs, excluding insulins | |||

| Glibenclamide | Risk of protracted hypoglycemia | Use conservative initial dose (1.25 mg/d for non-micronized glibenclamide; 0.75 mg/d for micronized glibenclamide) and maintenance dose; not recommended if CrCl <50 mL/min. M | Diet; metformin (<2 × 850 mg/d); insulin; gliclazide may be safer than the other short-acting sulphonilureas. E |

| Glimepiride | Risk of protracted hypoglycemia | Adjust according to renal function. E For patients with renal failure and for older people, use initial dose of 1 mg/d followed by a conservative titration scheme. Titrate dose in increments of 1 to 2 mg no more than every 1 to 2 weeks based on individual response. M | |

| Sitagliptine | Limited safety data available for adults aged ≥75 years old. Subjects aged 65 to 80 had higher plasma concentrations than younger subjects. Risk of hypoglycemia, dizziness, headache and peripheral oedema | Reduce dose to 50 mg/d in cases of renal failure (CrCl 30–50 mL/min); reduce dose to 25 mg/d in cases of severe renal insufficiency (CrCl <30 mL/min). E, M | |

| Antithrombotic agents | |||

| Acenocoumarol | Risk of bleeding, especially in people with difficult control of INR value | ||

| Dipyridamole | Less efficient than aspirin; risk of vasodilatation and orthostatic hypotension. Proven beneficial only for patients with artificial heart valves | Clopidogrel; aspirin (<325 mg)b. E, L | |

| Iron preparations | |||

| Iron supplements / Ferrous sulfate (>325 mg/d) | Doses >325 mg/d do not considerably increase the amount absorbed but greatly increase the incidence of constipation | Intravenous iron. E | |

| Cardiovascular system | |||

| Cardiac glycosides | |||

| Digitoxin | Elevated glycoside sensitivity in older people (women > men); risk of intoxication | Calculate digitalizing doses based on lean body mass and maintenance doses using actual CrCl. M | For tachycardia/atrial fibrillation: beta-blockers (except oxprenolol, pindolol, propranolol, sotalol, nadolol, labetalol). E, P For congestive heart failure: diuretics (except spironolactone >25 mg/d), ACE inhibitors. E |

| Digoxin | Calculate digitalizing doses based on lean body mass and maintenance doses using actual CrCl. M For older people, use dose 0.0625–0.125 mcg/d; in cases of renal failure (CrCl 10–50 mL/min), administer 25–75 % of dose or every 36 h; in cases of renal failure (CrCl <10 ml/min), administer 10–25 % of dose or every 48 h. E | ||

| Antiarrhythmics, classes I and III | |||

| Amiodarone | Associated with QT interval problems and risk of provoking torsades de pointes | Start dose at the low end of the dosing range. M Use lower maintenance dose, e.g. 200 mg/48 h. E | Data suggest that for most older people rate control yields better balance of benefits and harms than rhythm control for most of older people. B |

| Other cardiac preparations | |||

| Trimetazidine | Can cause or worsen parkinsonian symptoms (tremor, akinesia, hyperthonia); caution in cases of moderate renal failure and with older people (>75 years old); efficacy for the treatment of tinnitus or dizziness not proven | 20 mg twice per day for patients with moderate renal insufficiency. E | |

| Antiadrenergic agents, centrally acting | |||

| Rilmenidine | Risk of orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, syncope, CNS side effects (sedation, depression, cognitive impairment) | Reduce dose in cases of renal failure (CrCl <15 mL/min). M, E | Other antihypertensive drugs, e.g. ACE inhibitors, or other medication groups depending on comorbidity (exclude PIM). E |

| Antiadrenergic agents, peripherally acting | |||

| Doxazosin | Higher risk of orthostatic hypotension, dry mouth, urinary incontinence/ impaired micturition, CNS side effects (e.g. vertigo, light-headedness, somnolence) and cerebrovascular and cardiovascular disease | Start with half of usual dose, taper in and out. P Start with 0.5 mg/d (immediate release) or 4–8 mg/d (extended release). E | Other antihypertensive drugs, e.g. ACE inhibitors, or other medication groups depending on comorbidity (exclude PIM). E |

| Potassium-sparing agent | |||

| Spironolactone (>25 mg/d) | Higher risk of hyperkalaemia and hyponatremia in older people, especially if doses >25 mg/d, requiring periodic controls | Reduce dose in cases of moderate renal insufficiency. E, M GFR ≥50 mL/min/1.73 m: initial dose 12.5–25 mg/d, increase up to 25 mg 1–2/d; GFR 30–49 mL/min/1.73 m: initial dose 12.5 mg/d, increase up to 12.5–25 mg/d; reduce dose if potassium levels increase or renal function worsens. GFR <10 mL/min: avoid. M | Consider alternatives depending on the indication; exclude PIMs |

| Peripheral vasodilators | |||

| Pentoxifylline | No proven efficacy; unfavourable risk/benefit profile; orthostatic hypotension and fall risks are increased with most vasodilators | Reduce dose to 400 mg twice daily in cases of moderate renal failure and to 400 mg once daily in cases of severe renal failure; close monitoring for toxicities. Avoid use if CrCl <30 mL/min. M | |

| Beta blocking agents | |||

| Propranolol | Non-selective beta-adrenergic blocker; may exacerbate or cause respiratory depression; possible CNS adverse events | 3 doses of 20 mg daily E start low—go slow for older people and patients with renal failure. M | Depending on the indication: cardioselective beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, diuretics. E |

| Sotalol | Start at half or one third of the typical dose and increase slowly. P Reduce dose and dosing interval in cases of renal failure. M | Cardioselective beta-blockers (e.g. metoprolol, bisoprolol, carvedilol, atenolol). E | |

| Selective calcium channel blockers with mainly vascular effects | |||

| Nifedipine (non-sustained-release) | Increased risk of hypotension; myocardial infarction; increased mortality | Lower initial dose, half of usual dose, taper in and out. P | Other antihypertensive drugs (amlodipine, cardioselective beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, diuretics). E, L |

| Nifedipine (sustained-release) | Lower initial dose, half of usual dose, taper in and out. P Initial dose 30 mg/d; maintenance dose 30–60 mg/d. E | ||

| Selective calcium channel blockers with direct cardiac effects | |||

| Verapamil | May worsen constipation; risk of bradycardia | Immediate-release tablets: initial dose 40 mg three times daily; sustained release tablets initial dose 120 mg daily; oral controlled onset extended release initial dose 100 mg/d. M | Other antihypertensive drugs (amlodipine, cardioselective beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, diuretics). E |

| Diltiazem | Reduce dose or increase dosing interval. M 60 mg three times daily. E | ||

| Oestrogens | |||

| Oestrogen | Evidence for carcinogenic potential (breast and endometrial cancer) and lack of cardioprotective effect in older women | Specific treatment for osteoporosis. E Local administration (i.e. vaginal application) considered safe and efficient. E, B | |

| Other urologicals, including antispasmodics | |||

| Oxybutynine (non-sustained-release) | Anticholinergic side effects (e.g. constipation, dry mouth, CNS side effects); ECG changes (prolonged QT) | Start immediate-release oxybutynin chloride in frail older people with 2.5 mg orally 2 or 3 times daily. M | Non-pharmacological treatment (pelvic floor exercises, physical and behavioural therapy). E |

| Oxybutynine (sustained-release) | |||

| Tolterodine (non-sustained-release) | 1 mg orally twice daily in cases of significantly impaired renal function. M | ||

| Tolterodine (sustained-release) | Use 2 mg orally once daily in cases of severe renal failure (CrCl 10–30 mL/min); avoid use if CrCl <10 mL/min. M | ||

| Solifenacin | Dose reduction may be needed. M | ||

| Anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic products, non-steroid (NSAID) | |||

| Diclofenac | Very high risk of GI bleeding, ulceration, or perforation, which may be fatal; cardiovascular contraindications | 50 mg/d; start using low dose; the risk of bleeding may be reduced if combined with proton-pump inhibitors (use <8 weeks, low dose). E | Paracetamol; ibuprofen (≤3 × 400 mg/d or for a period shorter than one week); naproxen (≤2 × 250 mg/d or for a period shorter than one week). E Opiods with lower risk of delirium (e.g. tilidine/naloxone, morphineb, oxycodone, buprenorphine, hydromorphone). E, P |

| Dexketoprofen | Start with lower dose, up to 50 mg/d in older people; in postoperative pain: 50 mg/d in case of renal or hepatic failure, maximum dose 50 mg/8 h; maximum length 48 h; the risk of bleeding may be reduced if combined with proton-pump inhibitors (use <8 weeks, low dose). E | ||

| Etoricoxib | Shortest possible duration of therapy. P Start with lower dose; the risk of bleeding may be reduced if combined with proton-pump inhibitors (use <8 weeks, low dose). E | ||

| Meloxicam | Very high risk of GI bleeding, ulceration, or perforation, which may be fatal | 11 mg/d; start with lower dose; the risk of bleeding may be reduced if combined with proton-pump inhibitors (use <8 weeks, low dose). E | |

| Ibuprofen (>3 × 400 mg/d or for a period longer than one week) | Risk of GI bleeding and increased risk of cardiovascular complications at higher doses (>1200 mg/d), especially in case of previous cardiovascular disease | The risk of bleeding may be reduced if combined with proton-pump inhibitors (use <8 weeks, low dose). E | |

| Drugs affecting bone structure and mineralization | |||

| Strontium ranelate | Higher risk of venous thromboembolism in persons who are temporarily or permanently immobilised. Evaluate the need for continued therapy for patients over 80 years old with increased risk of venous thromboembolism | Avoid in cases of severe renal failure (CrCl <30 mL/min). M | Bisphosphonates, vitamin D. E |

| Opioids | |||

| Tramadol (sustained-release) | More adverse effects in older people; CNS side effects such as confusion, vertigo and nausea | Start low—go slow. Not to be used in cases of severe renal failure. E, M | Paracetamol; ibuprofen (≤3 × 400 mg/d or for a period shorter than one week); naproxen (≤2 × 250 mg/d or for a period shorter than one week). E Opioids with lower risk of delirium (e.g. tilidine/naloxone, morphineb, oxycodone, buprenorphine, hydromorphone). E, P |

| Tramadol (non-sustained-release) | Start low—go slow; in persons older than 75 years, daily doses over 300 mg are not recommended. M Start with 12.5 mg/8 h and progressive increases of 12.5 mg/8 h; maximum 100 mg/8 h. E Reduce dose and extend the dosing interval for patients with severe renal failure. M | ||

| Antiepileptics | |||

| Clonazepam | Risk of falls, paradoxical reactions. | Start low—go slow; 0.5 mg/day. E | Levetiracetamb; gabapentinb; lamotrigineb; valproic acidb. E |

| Carbamazepine | Increased risk of SIADH-like syndrome; adverse events like carbamazepine-induced confusion and agitation, atrioventricular block and bradycardia | Adjust dose to the response and serum concentration. E | |

| Dopaminergic agents | |||

| Ropinirole | Risk of orthostatic hypotension, hallucinations, confusion, somnolence, nausea | Start with three intakes of 0.25 mg per day, increase gradually by 0.25 mg per intake each week for four weeks, up to 3 mg/d. Afterwards the dose may be increased weekly by 1.5 mg/d up to 24 mg/d. E | Levodopa; carbidopa-levodopa; benserazide levodopa; irreversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase as rasagiline. E |

| Pramipexole | Side effects include orthostatic hypotension, GI tract symptoms, hallucinations, confusion, insomnia, peripheral oedema | Reduce dose in cases of moderate to severe renal failure. M Start with three intakes of 0.125 per day, increase gradually by 0.125 mg per intake every five to seven days, up to 1.5 to 4.5 mg. E | |

| Antipsychotics | |||

| Chlorpromazine | Muscarinic-blocking drug; risk of orthostatic hypotension and falls; may lower seizure thresholds in patients with seizures or epilepsy | Start low—go slow; use one third to one half the normal adult dose for debilitated older people; use maintenance doses of 300 mg or less; doses greater than 1 g do not usually offer any benefit, but may be responsible for an increased incidence of adverse effects. M | Non-pharmacological treatment; risperidone (<6 weeks), olanzapine (<10 mg/d), haloperidol (<2 mg single dose; < 5 mg/d); quetiapineb. E |

| Levomepromazine | Anticholinergic and extrapyramidal side effects (tardive dyskinesia); parkinsonism; hypotonia; sedation; risk of falling; increased mortality in persons with dementia | Administer cautiously in cases of renal failure; start with doses of 5 to 10 mg in geriatric patients. M | |

| Haloperidol (>2 mg single dose; >5 mg/d) | Use oral doses of 0.75-1.5 mg; use for the shortest period possible. E | ||

| Zuclopenthixol | Risk of hypotension, falls, extrapyramidal effects, QTc-prolongation | Use low oral doses of 2.5–5 mg/d. M | |

| Clozapine | Anticholinergic and extrapyramidal side effects (tardive dyskinesia); parkinsonism; hypotonia; sedation; risk of falling; increased mortality in persons with dementia; increased risk of agranulocytosis and myocarditis | Start with 12.5 mg/d. E Start low—go slow; reduce dose in cases of significant renal failure. M | |

| Risperidone (>6 weeks) | Problematic risk-benefit profile for the treatment of behavioural symptoms of dementia; increased mortality, with higher dose, in patients with dementia | Use the lowest dose required (0.5–1.5 mg/d) for the shortest time period necessary. E For geriatric patients or in cases of severe renal failure (CrCl <30 mL/min), start with 0.5 mg twice daily; increase doses by 0.5 mg twice daily; increases above 1.5 mg twice daily should be done at intervals of at least 1 week; slower titration may be necessary. For geriatric patients, if once-daily dosing desired, initiate and titrate on a twice-daily regimen for 2 to 3 days to achieve target dose and switch to once-daily dosing thereafter. M | |

| Anxiolytics | |||

| Diazepam | Risk of falling with hip fracture; prolonged reaction times; psychiatric reactions (can also be paradoxical, e.g. agitation, irritability, hallucinations, psychosis); cognitive impairment; depression | Use the lowest possible dose, up to half of the usual dose, taper in and out, shortest possible duration of treatment. P, M Use initial oral dose of 2–2.5 mg once a day to twice a day. M | Non-pharmacological treatment; low doses of short-acting benzodiazepines such as lormetazepam (≤0.5 mg/d), brotizolam (≤0.125 mg/d); antidepressants with anxiolytic profile (SSRIc). E, P If used as hypnotics or sedatives: see alternatives proposed for “hypnotics and sedatives” |

| Lorazepam (>1 mg/d) | Reduce dose; use doses of 0.25–1 mg/d. E | ||

| Bromazepam | Use the lowest possible dose, up to half of the usual dose, taper in and out according to individual response, shortest possible duration of treatment. P, M | ||

| Alprazolam | Use the lowest possible dose, up to half of the usual dose, taper in and out, shortest possible duration of treatment. P Starting dose 0.25 mg/12 h. E Immediate release tablets (including orally disintegrating tablets): start with 0.25 mg administered two to three times a day and titrate as tolerated; extended-release tablets: start with 0.5 mg once daily, gradually increase as needed and tolerated. M | ||

| Hypnotics and sedatives | |||

| Flunitrazepam | Risk of falls and hip fracture, prolonged reaction time, psychiatric reactions (which can be paradoxical, e.g. agitation, irritability, hallucinations, psychosis), cognitive impairment and depression | Use the lowest possible dose, up to half of the usual dose, taper in and out, shortest possible duration of treatment. P Reduce dose, e.g. 0.5 mg/d; start low—go slow. E, M For induction of anaesthesia in older, poor-risk people, titrate dose carefully; administer in small intravenous increments of 0.3 to 0.5 mg, at 30-s intervals. M | Non-pharmacological treatment; mirtazapineb; passiflora, low doses of short-acting benzodiazepines such as lormetazepam (≤0.5 mg/d), brotizolam (≤0.125 mg/d); zolpidem (≤5 mg/d), zopiclon (≤3.75 mg/d), zaleplon (≤5 mg/d); trazodone. E, P |

| Lormetazepam (>0.5 mg/d) | Use the lowest possible dose, up to half of the usual dose, taper in and out, shortest possible duration of treatment. P | ||

| Temazepam | Use the lowest possible dose, up to half of the usual dose, taper in and out, shortest possible duration of treatment. P Start with 7.5 mg/d and watch individual response. M | ||

| Zopiclone (>3.75 mg/d) | Use the lowest possible dose, up to half of the usual dose, taper in and out, shortest possible duration of treatment. P | ||

| Zolpidem (>5 mg/d) | |||

| Clomethiazole | Risk of respiratory depression | Reduce dose. E, M Use sedative dose 500–1000 mg at bedtime. M | |

| Antidepressants | |||

| Amitriptyline | Peripheral anticholinergic side effects (e.g. constipation, dry mouth, orthostatic hypotension, cardiac arrhythmia); central anticholinergic side effects (drowsiness, inner unrest, confusion, other types of delirium); cognitive deficit; increased risk of falling | Start at half the usual daily dose, increase slowly; reduce dose; start with 10 mg 3 times per day and 20 mg at bedtime. M, E, P Its use for treating neuropathic pain may be considered appropriate, with benefits overweighting the risks. E | Non-pharmacological treatment, SSRI (except PIM: fluoxetine, paroxetine, fluvoxamine)c, mirtazapineb, trazodone. E |

| Nortriptyline | Use 30–50 mg/d in divided doses. E, M Its use for treating neuropathic pain may be considered appropriate, with benefits overweighting the risks. E | ||

| Fluoxetine | CNS side effects (nausea, insomnia, dizziness, confusion); hyponatremia | Reduce dose; start with 20 mg/d; maximum dose also 20 mg/d; avoid administration at bedtime. E, M | |

| Paroxetine | Higher risk of all-cause mortality, higher risk of seizures, falls and fractures. Anticholinergic adverse effects | For older people or for patients with renal failure, start immediate-release tablets with 10 mg/d (12.5 mg/d if controlled-release tablets), increased by 10 mg/d (12.5 mg/d if controlled-release tablets), up to 40 mg/d (50 mg/d if controlled-release tablets). E, M | |

| Venlafaxine | Higher risk of all-cause mortality, attempted suicide, stroke, seizures, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, falls and fracture | Start with 25–50 mg, two times per day and increase by 25 mg/dose; for extended-release formulation start with 37.5 mg once daily and increase by 37.5 mg every 4–7 days as tolerated. E Reduce the total daily dose by 25–50 % in cases of mild to moderate renal failure. M | |

| Psychostimulants, agents used for ADHD and nootropics | |||

| Piracetam | No efficacy proven; unfavourable risk/benefit profile | Reduce dose for older people and for patients with renal failure. M | Non-pharmacological treatment; consider pharmacotherapy of Alzheimer-type dementia: acetylcholinesterase, memantine. E |

| Anti-dementia drugs | |||

| Ginkgo biloba | No efficacy proven; increased risk of orthostatic hypotension and fall | Non-pharmacological treatment; consider pharmacotherapy of Alzheimer-type dementia: acetylcholinesterase, memantine. E | |

| Other systemic drugs for airway diseases | |||

| Theophylline | Higher risk of CNS stimulant effects | Start with a 25 % reduction compared to the doses for younger people. E Start with a maximum dose of 400 mg/d; monitor serum levels and reduce doses if needed; for healthy older people (>60 years), theophylline clearance is decreased by an average of 30 %. M | |

| Cough suppressants, excluding combinations with expectorants | |||

| Codeine (>2 weeks) | Higher risk of adverse events (hypotension, sweating, constipation, vomiting, dizziness, sedation, respiratory depression). Avoid use for longer than 2 weeks for persons with chronic constipation without concurrent use of laxatives and for persons with renal impairment | Start treatment cautiously for older people (especially in cases of renal failure); start low—go slow; reduce dose to 75 % of the usual dose if GFR 10–50 mL/min and to 50 % if GFR <10 mL/min. M | If used for pain management consider alternative drugs proposed for “anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic products, non-steroid (NSAID)” |

| Antihistamines for systemic use | |||

| Promethazine | Anticholinergic side effects (e.g. confusion, sedation) | Reduce dose; start low—go slow. M Reduce starting dose to 6.25–12.5 mg for iv injection. M | Non-sedating, non-anticholinergic antihistaminesd like loratadine, cetirizine, but not terfenadine (which is PIM). E If used for insomnia see alternatives proposed for “hypnotics and sedatives” |

| Hydroxyzine | Anticholinergic side effects (e.g. constipation, dry mouth); impaired cognitive performance, confusion, sedation; electrocardiographic changes (prolonged QT) | Reduce dose to at least 50 % less than dose used for healthy younger people. E, M | Non-sedating, non-anticholinergic antihistaminesd like loratadine, cetirizine, but not terfenadine (which is PIM). E Alternative therapies depending on indication. E |

Note: if nothing is stated under “Dose adjustment/special considerations of use”, this means that no suggestion was made either by the experts or in Micromedex®

E experts, M Micromedex® [32], P PRISCUS list [22], L Laroche et al. (2007) [3], B Beers list (2012) [18], ACE angiotensin-converting enzyme, CNS central nervous system, ECG electrocardiographic, GI gastrointestinal, PIM potentially inappropriate medication, PPI proton-pump inhibitors, RTPC RightTimePlaceCare [23], SIADH syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion, ADHD attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

Dosage abbreviations: CrCl creatinine clearance, d day, GFR glomerular filtration rate, iv intravenous, mcg micrograms, mg milligram, min minute, mL millilitre, q every

aOnly the details on the drugs most commonly used in the RTPC database are presented—see also EU(7)-PIM long version in Appendix 1

bCaution: this drug was judged to be questionable PIM

cThe following drugs belonging to this medication group were judged to be questionable PIM: citalopram, sertraline, and escitalopram

dIn the group of non-sedating antihistamines, only loratadine was evaluated and judged to be questionable PIM; other drugs such as cetirizine were not evaluated

Appendix 1 shows the complete EU(7)-PIM list, which comprises 275 chemical substances (i.e. 7-digit ATC codes; e.g. amitriptyline) including two combinations of two chemical substances, plus seven drug classes (i.e. 5-digit ATC codes; e.g. triptans), belonging to 55 therapeutic classes (i.e. 4-digit ATC codes; e.g. antidepressants) and 34 therapeutic groups (i.e. 3-digit ATC codes; e.g. the nervous system). Some PIM concepts are dose-related (e.g. zopiclone used at doses higher than 3.75 mg/day) or defined by length of use (e.g. proton-pump inhibitors used longer than 8 weeks) or drug regimen (e.g. insulin, sliding scale). Appendix 1 contains also information on the number of experts who assessed each PIM, the mean, median and standard deviation of the scores given by experts to each drug (Likert scale), and the results of the compilation and selection of suggestions for dose adjustments and therapeutic alternatives. Furthermore, Appendix 1 shows two categories of those drugs (active substances characterised by their ATC code) on the EU-PIM list that are included also on other PIM lists. Category A means that precisely this active substance is named as a PIM which should be avoided in older people. Category B means that (i) this active substance is characterised as a PIM only in the case of certain clinical conditions or co-morbidities or (ii) this active substance is not specifically named but considered as a PIM drug class (e.g. anticholinergics or long-acting benzodiazepines). This information refers to six international PIM lists or criteria [3, 18, 19, 22, 26, 33] and shows that 24 drugs do not appear as PIM in any of the other lists, while the rest varies from appearing in one list only to appearing in all the lists.

The full lists of questionable PIM and non-PIM and the results of their assessments are presented in Appendix 2 and 3, respectively.

Discussion

We developed the EU(7)-PIM list in order to analyse the prescription patterns of potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) across several European countries, and more specifically among the people with dementia participating in the RightTimePlaceCare Seventh Framework European project [23]. We also aimed to develop a list that would be applicable in clinical practice. The development of the EU(7)-PIM list took several international PIM lists (i.e. the German PRISCUS list [22], the American Beers list [18, 24, 25], the Canadian list [26], and the French list [3]) into consideration, as well as further drugs suggested by experts on geriatric prescribing from seven European countries who belonged to different professions.

The EU(7)-PIM list can be seen as a screening tool for the identification of PIM for older people across many European countries. We have covered several regions of Europe including Finland and Sweden in Scandinavia, France and Spain in southern Europe, Germany and the Netherlands in central Europe, and Estonia in eastern Europe. As shown by Fialová et al. [5], the prevalence of PIM use in several European countries varies widely, depending on the PIM criteria set. Thus, the creation of a PIM list suitable for pharmacoepidemiological studies and clinical use in Europe seems to be mandatory. Attempts are being undertaken to develop prescribing quality indicators which are useful for the electronic monitoring of the quality of prescribing in older people in Europe [34], and the EU(7)-PIM list could represent a part of this.

We expect the EU(7)-PIM list to be a sensitive tool because of its inclusive development process. In contrast, other tools have been seen to be less sensitive, motivating some authors to use two or three assessment tools for the assessment of PIM use in their populations in order to increase the sensitivity [5, 6, 35, 36].

We aimed at developing a list which can be used even if the clinical information available is minimal. Therefore, we chose to develop explicit PIM criteria, restricted to drugs or drug classes, in some instances restricted to high doses or prolonged treatment duration. Thus, the EU(7)-PIM list is suitable for pharmacoepidemiological applications using administrative databases or surveys without any clinical information about the individuals concerned.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first list focusing on chemical substances and requiring only a small amount of clinical data for its application that has been developed taking into account several existing PIM lists and European markets, and that has been consented by experts from different European countries. This is also one of the few lists including suggestions for dose adjustments and therapeutic alternatives. Furthermore, the list enables a distinction between different drugs belonging to the same pharmacological subgroup and provides different suggestions for each of them. The recently published screening tool of older person’s prescriptions (STOPP)/screening tool to alert doctors to right treatment (START) criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing for older people (version 2) were developed also with the participation of a European panel of experts [19]. However, these criteria often consider as PIM the use of pharmacological subgroups (e.g. thiazide diuretics) within specific clinical contexts (e.g. history of gout, or current significant hypokalaemia). Thus, the application of the START/STOPP criteria (both versions 1 and 2) [4, 19] requires clinical information, making these criteria more suitable in the clinical context for a comprehensive drug review of individual patients.

The development process of the EU(7)-PIM list resembles those of most other PIM lists, such as the French list [3], the German PRISCUS list [22], the Austrian PIM list [37], but also the most recent Beers list [18]. One major aspect of criticism of all PIM lists is that the classification of PIM is usually done without using evidence derived from randomised, controlled trials and relies on the expertise of the participants in the Delphi process [38]. However, this is partially justified by the lack of evidence on drug efficacy and safety in older people, due to their low enrolment in clinical trials [17]. In our study, we identified relevant literature and used it during the development process, but we did not systematically review and report it, which may be seen as a limitation.

The Delphi technique has also been criticised because of the lack of one standardised method, the difficulties in analysing the data, the difficulties in defining what an expert is, the often heterogeneous expert group, and the vague concept of consensus [38]. In order to minimise the limitations of the Delphi technique, in the present study, the characteristics of the survey were predefined (e.g. steps, consensus concept), and researchers provided experts with all necessary information to favour their engagement and participation. Researchers compiled discussion issues raised by the experts and took them into consideration for the consecutive steps of the development process.

Only seven European countries participated in the development of the EU(7)-PIM list (Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain and Sweden). Furthermore, the number of experts participating from some countries was limited. Certain drugs may not have been assessed for appropriateness because they were neither included in the preliminary list nor were they suggested by the experts. Certain drugs were classified as PIM with a lower level of expert agreement than others; some disagreements seemed related to the experts’ country of origin, which may show that there are international differences in prescription patterns or attitudes. Regular updates of the list should take into consideration the inclusion of other European markets, the changes in the drug markets, the prescribing tendencies, and above all, the new existing evidence.

The application of the EU(7)-PIM list cannot substitute the individual assessment of prescribing appropriateness, which should take into account other aspects such as the aims of the treatment, individual responses, and the older person’s functional level, values and preferences, among others [39]. This limitation has been recognised in the literature with regard to most tools assessing appropriateness of prescription [16]. Despite its limitations, the concept of PIM suggests that their use should be associated with less favourable outcomes. Indeed, the use of PIM has been found associated with a higher rate of adverse drug reactions in several studies, as reported in a systematic review [40], with some variations depending on the settings studied. Other authors have suggested an association between PIM use and other adverse outcomes such as injuries [41] and hospitalisation [6, 14]. A limited number of studies on interventions involving the use of some of these tools have suggested benefits in terms or relevant outcomes [42–44]. However, according to a recent systematic review, it is unclear whether such interventions result in clinically significant improvements, although benefits in terms of reducing inappropriate prescribing may exist [45].

Future research should study whether the use of PIM according to the EU(7)-PIM list shows any association with clinically relevant outcomes for older people, and whether the application of the list is associated with any benefits, both in a population and on individual levels. The acceptability of the list among health professionals should also be investigated, including the usefulness of the suggestions for drug adjustments and therapeutic alternatives.

In conclusion, the EU(7)-PIM list is an expert-consensus list of potentially inappropriate medications for older people, which was developed taking into consideration the medications appearing in six country-specific PIM lists, as well as medications used in seven European countries. It is an explicit list of chemical substances and contains suggestions for dose adjustments and therapeutic alternatives. It can be applied as a screening tool to identify potentially inappropriate medications in databases where little clinical information is available and in individual data. It can also be used for international comparisons of the prescription patterns of PIMs and may be used as a guide in the clinical practice. The application of the EU(7)-PIM list is a first step towards the identification of areas of improvement in both individual and population levels and towards the harmonisation of the prescription quality throughout Europe.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 586 kb)

(DOCX 25.9 kb)

(DOCX 19 kb)

Acknowledgments

We are very thankful to the following experts on geriatric prescribing and/or pharmacotherapy for their participation in the development process of the EU(7)-PIM list: Anti Kalda (University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia), Jana Lass (University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia), Mai Rosenberg (University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia), Peeter Saadla (Tartu University Hospital, Tartu, Estonia), Kai Saks (University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia), Gennadi Timberg (West-Tallinn Central Hospital and MedTIM Private Urological Clinic, Tallinn, Estonia), Tiina Uuetoa (East-Tallinn Central Hospital, Tallinn, Estonia), Risto Huupponen (University of Turku, Turku, Finland), Paula Viikari (Turku City Hospital, Turku, Finland), Matti Viitanen (University of Turku, Turku, Finland), François Montastruc (Toulouse University Hospital, Toulouse, France), Antoine Piau (Toulouse University Hospital, Toulouse, France), Froukje Boersma (University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands), Paul A. F. Jansen (Expertise Centre Pharmacotherapy in Old Persons (EPHOR) Utrecht, the Netherlands), Rob van Marum (Jeroen Bosch Hospital, ‘s Hertogenbosch, VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), Jos M. G. A. Schols (University of Maastricht, Maastricht, the Netherlands), Eva Delgado-Silveira (University Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain), Antonio Fernandez Moyano (San Juan de Dios del Aljarafe Hospital, Sevilla, Spain), Francesc Formiga (University Hospital of Bellvitge, Barcelona, Spain), Elisabet de Jaime (Parc de Salut Mar, Barcelona, Spain), Ramón Miralles (Parc de Salut Mar, Barcelona, Spain), María Muñoz (University Hospital Ramón y Cajal, Madrid, Spain), Olga Vázquez (Parc de Salut Mar, Barcelona, Spain), Robert Eggertsen (University of Gothenburg, Sahlgrenska Academy, Gothenburg, Sweden), Peter Engfeldt (Örebro University, Örebro, Sweden), Tommy Eriksson (Lund University, Lund, Sweden), Johan Fastbom (Karolinska Institute and Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden), Annika Kragh (Lund University, Lund, Sweden), Patrik Midlöv (Center for Primary Health Care Research, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden), and Anders Wimo (Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden).

We thank Dr Stefanie Holt-Noreiks and Dr Simone Bernard, University of Witten/Herdecke, for their scientific contribution throughout the project. We also thank Ms Vivienne Krause, University of Witten/Herdecke, who checked the manuscript and the EU(7)-PIM list for the English language; Ms Klaaßen-Mielke, Ruhr University Bochum, who contributed in the coding and plausibility checks of the list; and Ms Malin Wörster, who contributed in comparing the EU(7)-PIM list with other international lists. We are thankful to the RTPC Consortium partners who supported us to establish the contact to the experts. Finally, we thank the University of Witten/Herdecke for supporting the project and the Sociedad Española de Geriatría y Gerontología (Spanish Society of Geriatric Medicine and Gerontology) for supporting the work of the first author of this study with a grant.

Compliance with ethical standards

ᅟ

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This study was supported by a research grant of the University of Witten/Herdecke.

Contributions of authors’ statement

Petra A Thürmann (PAT) and Gabriele Meyer (GM) conceptualised the study and applied for funding. Anna Renom-Guiteras (ARG) and PAT prepared the work documents during the development process. ARG recruited the experts and coordinated the expansion phase, the Delphi survey and the last brief questionnaire. PAT and ARG prepared the final version of the EU(7)-PIM list. ARG drafted the manuscript, supported by GM and PAT. All the authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Dimitrow MS, Airaksinen MS, Kivela SL, Lyles A, Leikola SN. Comparison of prescribing criteria to evaluate the appropriateness of drug treatment in individuals aged 65 and older: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(8):1521–1530. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spinewine A, Schmader KE, Barber N, Hughes C, Lapane KL, Swine C, Hanlon JT. Appropriate prescribing in elderly people: how well can it be measured and optimised? Lancet. 2007;370(9582):173–184. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laroche ML, Charmes JP, Merle L. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: a French consensus panel list. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;63(8):725–731. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0324-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, Kennedy J, O’Mahony D. STOPP (screening tool of older person’s prescriptions) and START (screening tool to alert doctors to right treatment). Consensus validation. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;46(2):72–83. doi: 10.5414/CPP46072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fialova D, Topinkova E, Gambassi G, Finne-Soveri H, Jonsson PV, Carpenter I, Schroll M, Onder G, Sorbye LW, Wagner C, Reissigova J, Bernabei R. Potentially inappropriate medication use among elderly home care patients in Europe. JAMA. 2005;293(11):1348–1358. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.11.1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reich O, Rosemann T, Rapold R, Blozik E, Senn O. Potentially inappropriate medication use in older patients in Swiss managed care plans: prevalence, determinants and association with hospitalization. PLoS One. 2014;9(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallagher P, O’Mahony D. STOPP (screening tool of older persons’ potentially inappropriate prescriptions): application to acutely ill elderly patients and comparison with Beers’ criteria. Age Ageing. 2008;37(6):673–679. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallagher P, Lang PO, Cherubini A, Topinkova E, Cruz-Jentoft A, Montero Errasquin B, Madlova P, Gasperini B, Baeyens H, Baeyens JP, Michel JP, O’Mahony D. Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in an acutely ill population of older patients admitted to six European hospitals. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;67(11):1175–1188. doi: 10.1007/s00228-011-1061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Gollarte F, Baleriola-Julvez J, Ferrero-Lopez I, Cruz-Jentoft AJ. Inappropriate drug prescription at nursing home admission. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(1):83 e9–83 e15. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mann E, Haastert B, Frühwald T, Sauermann R, Hinteregger M, Hölzl D, Keuerleber S, Scheuringer M, Meyer G. Potentially inappropriate medication in older persons in Austria: a nationwide prevalence study. Eur Geriatr Med. 2014;5(6):399–405. doi: 10.1016/j.eurger.2014.06.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang CM, Liu PY, Yang YH, Yang YC, Wu CF, Lu FH. Use of the Beers criteria to predict adverse drug reactions among first-visit elderly outpatients. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25(6):831–838. doi: 10.1592/phco.2005.25.6.831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Passarelli MC, Jacob-Filho W, Figueras A. Adverse drug reactions in an elderly hospitalised population: inappropriate prescription is a leading cause. Drugs Aging. 2005;22(9):767–777. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200522090-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamilton H, Gallagher P, Ryan C, Byrne S, O’Mahony D. Potentially inappropriate medications defined by STOPP criteria and the risk of adverse drug events in older hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(11):1013–1019. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price SD, Holman CD, Sanfilippo FM, Emery JD. Association between potentially inappropriate medications from the Beers criteria and the risk of unplanned hospitalization in elderly patients. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(1):6–16. doi: 10.1177/1060028013504904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gosch M, Wortz M, Nicholas JA, Doshi HK, Kammerlander C, Lechleitner M. Inappropriate prescribing as a predictor for long-term mortality after hip fracture. Gerontology. 2014;60(2):114–122. doi: 10.1159/000355327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaufmann CP, Tremp R, Hersberger KE, Lampert ML. Inappropriate prescribing: a systematic overview of published assessment tools. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s00228-013-1575-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell SM, Cantrill JA. Consensus methods in prescribing research. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2001;26(1):5–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2001.00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert P American Geriatrics Society updated Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, O’Connor MN, Ryan C, Gallagher P. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing. 2014 doi: 10.1093/ageing/afu145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shelton PS, Fritsch MA, Scott MA. Assessing medication appropriateness in the elderly: a review of available measures. Drugs Aging. 2000;16(6):437–450. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200016060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, McGlynn EA, Campbell S, Brook RH, Roland MO. Can health care quality indicators be transferred between countries? Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(1):8–12. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.1.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holt S, Schmiedl S, Thurmann PA. Potentially inappropriate medications in the elderly: the PRISCUS list. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107(31-32):543–551. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verbeek H, Meyer G, Leino-Kilpi H, Zabalegui A, Hallberg IR, Saks K, Soto ME, Challis D, Sauerland D, Hamers JP. A European study investigating patterns of transition from home care towards institutional dementia care: the protocol of a RightTimePlaceCare study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:68. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beers MH. Explicit criteria for determining potentially inappropriate medication use by the elderly. An update. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(14):1531–1536. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1997.00440350031003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fick DM, Cooper JW, Wade WE, Waller JL, Maclean JR, Beers MH. Updating the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults: results of a US consensus panel of experts. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(22):2716–2724. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.22.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McLeod PJ, Huang AR, Tamblyn RM, Gayton DC. Defining inappropriate practices in prescribing for elderly people: a national consensus panel. CMAJ. 1997;156(3):385–391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schubert I, Kupper-Nybelen J, Ihle P, Thurmann P. Prescribing potentially inappropriate medication (PIM) in Germany’s elderly as indicated by the PRISCUS list. An analysis based on regional claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(7):719–727. doi: 10.1002/pds.3429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Montastruc F, Gardette V, Cantet C, Piau A, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Vellas B, Montastruc JL, Andrieu S. Potentially inappropriate medication use among patients with Alzheimer disease in the REAL.FR cohort: be aware of atropinic and benzodiazepine drugs! Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(8):1589–1597. doi: 10.1007/s00228-013-1506-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fick DM, Maclean JR, Rodriguez NA, Short L, Heuvel RV, Waller JL, Rogers RL. A randomized study to decrease the use of potentially inappropriate medications among community-dwelling older adults in a southeastern managed care organization. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(11 Pt 1):761–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The anatomical therapeutic chemical classification system and the defined daily dose. Internet database. WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, Norwegian Institute of Public Health. Nydalen, Oslo, Norway. http://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index/. Accessed 17 February 2015

- 31.Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311(7001):376–380. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Truven health micromedex solutions. Internet database. Greenwood Village, Colorado, USA. http://www.micromedexsolutions.com/home/dispatch. Accessed 31 October 2014

- 33.Finnish Medicines Agency. Database of medication for the elderly. Internet database. http://www.fimea.fi/medicines/medicines_assesment/. Accessed 19 February 2015

- 34.European Science Foundation (2015). Workshops detail: enhancing the quality and safety of pharmacotherapy in old age. http://www.esf.org/coordinating-research/exploratory-workshops/workshops-list/workshops-detail.html?ew=13023. Accessed 20 April 2015

- 35.Siebert S, Elkeles B, Hempel G, Kruse J, Smollich M. The PRISCUS list in clinical routine. Practicability and comparison to international PIM lists. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;46(1):35–47. doi: 10.1007/s00391-012-0324-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elseviers MM, Vander Stichele RR, Van Bortel L. Quality of prescribing in Belgian nursing homes: an electronic assessment of the medication chart. Int J Qual Health Care. 2014;26(1):93–99. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzt089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mann E, Bohmdorfer B, Fruhwald T, Roller-Wirnsberger RE, Dovjak P, Duckelmann-Hofer C, Fischer P, Rabady S, Iglseder B. Potentially inappropriate medication in geriatric patients: the Austrian consensus panel list. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2012;124(5-6):160–169. doi: 10.1007/s00508-011-0061-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marriott J, Stehlik P. A critical analysis of the methods used to develop explicit clinical criteria for use in older people. Age Ageing. 2012;41(4):441–450. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afs064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steinman MA, Hanlon JT. Managing medications in clinically complex elders: there’s got to be a happy medium. JAMA. 2010;304(14):1592–1601. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jano E, Aparasu RR. Healthcare outcomes associated with beers’ criteria: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(3):438–447. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bauer TK, Lindenbaum K, Stroka MA, Engel S, Linder R, Verheyen F. Fall risk increasing drugs and injuries of the frail elderly—evidence from administrative data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(12):1321–1327. doi: 10.1002/pds.3357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hill-Taylor B, Sketris I, Hayden J, Byrne S, O’Sullivan D, Christie R. Application of the STOPP/START criteria: a systematic review of the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing in older adults, and evidence of clinical, humanistic and economic impact. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2013;38(5):360–372. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frankenthal D, Lerman Y, Kalendaryev E, Lerman Y. Intervention with the screening tool of older persons potentially inappropriate prescriptions/screening tool to alert doctors to right treatment criteria in elderly residents of a chronic geriatric facility: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(9):1658–1665. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Blozik E, Born AM, Stuck AE, Benninger U, Gillmann G, Clough-Gorr KM. Reduction of inappropriate medications among older nursing-home residents: a nurse-led, pre/post-design, intervention study. Drugs Aging. 2010;27(12):1009–1017. doi: 10.2165/11584770-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patterson SM, Cadogan CA, Kerse N, Cardwell CR, Bradley MC, Ryan C, Hughes C. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;10 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008165.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.ATC classification with defined daily dose DDD. Internet database. German Institute of Medical Documentation and Information. https://www.dimdi.de/dynamic/en/contact.html. Accessed 17 February 2015

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 586 kb)

(DOCX 25.9 kb)

(DOCX 19 kb)