Abstract

Aims. Metastatic malignant melanoma of the urinary bladder is a rare clinical entity, with only twenty-three published cases to date. We present a case of this rare entity, a thorough review of the literature, and differential diagnosis of melanoma in the bladder. Methods and Results. A 55-year-old woman with a history of malignant melanoma of the right thigh, excised eight years ago, presented with back pain, fatigue, and hematuria. She underwent computed tomography (CT) scan and was found to have metastases within the liver, spleen, lungs, and urinary bladder. She underwent cystoscopy and transurethral resection of three polypoid lesions. Histologic and immunohistochemical examination revealed metastatic malignant melanoma involving bladder mucosa. Conclusions. This case illustrates the importance of including malignant melanoma in the differential diagnosis of high grade neoplasms of bladder, especially in cases where the relevant clinical history is not available.

1. Introduction

Metastasis of malignant melanoma to the bladder is extremely rare in clinical practice. Although many recent review papers report less than ten cases in the past thirty years, our thorough review of the current literature reveals 23 confirmed cases published to date. This indicates that the incidence is likely higher than previously thought and may be due to the fact that many patients are asymptomatic and only found at autopsy. In 1964, Das Gupta and Brasfield performed an autopsy series of 125 patients with metastatic melanoma and found that 18% had metastases to the bladder [1]. Similarly in 2000, Bates and Baithun described five postmortem cases of melanoma metastasizing to the urinary bladder among 153 autopsy cases [2]. Symptomatic patients, on the other hand, usually present with painless gross hematuria [3]. The most common sites of metastasis include regional lymph nodes, lungs, liver, and brain. Malignant melanoma is extremely diverse in its histologic, cytological, and architectural appearances and is often known as the “great mimicker.” This holds true for metastases to the urinary bladder. Our case highlights the importance of including malignant melanoma in the differential diagnosis of high grade urothelial lesions. Although a clinical history of melanoma is often the first clue to the diagnosis, this clinical information is not always readily available.

2. Materials and Methods

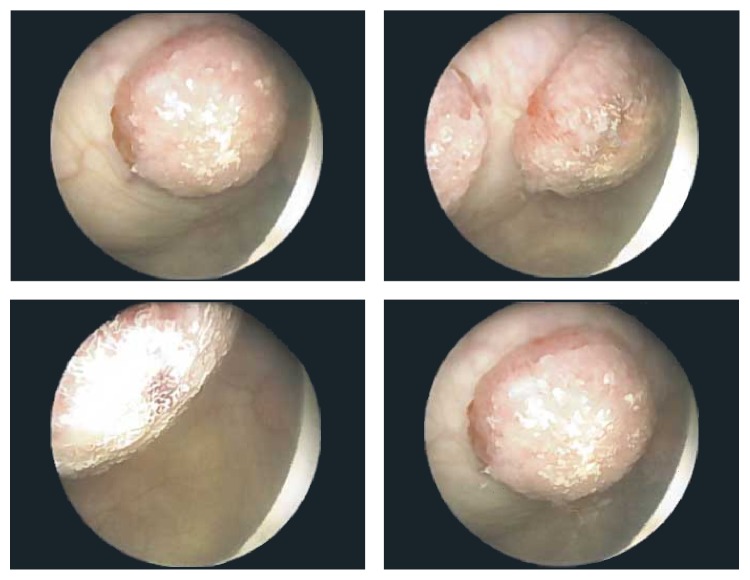

A 55-year-old woman presented with back pain, generalized fatigue, and hematuria. Her past medical history was significant for malignant melanoma of the right thigh, diagnosed eight years ago, for which she underwent wide local excision and sentinel lymph node biopsy. Biopsy revealed that the melanoma was 1.05 mm in thickness, Clark's level IV, and without ulceration. One sentinel lymph node was removed which was negative for metastatic disease. Reexcision revealed the presence of scar with no evidence of residual disease. She was followed up regularly and remained asymptomatic, until eight years later when she developed back pain and generalized fatigue. She was evaluated by her primary care physician and tested negative for Lyme disease. Shortly afterwards, she developed hematuria and was referred to urology for further evaluation. Urinalysis ruled out infection and confirmed the presence of hematuria. She also had computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which revealed multiple liver and splenic lesions, multiple subcentimeter bilateral pulmonary nodules suspicious for metastatic disease, and several masses within the bladder, measuring up to 1.9 cm in greatest dimension. Urine cytology identified atypical cells, but evaluation was limited by scant cellularity. She underwent cystoscopy, which revealed three polypoid, spherical lesions, each protruding from a stalk (Figure 1). Two of these lesions were located along the left anterior bladder dome and measured approximately 2 cm each. A third smaller lesion, located along the left lateral bladder wall, measured approximately 1 cm. There was no evidence of discoloration in the lesions or elsewhere in the bladder. Monopolar loop electrocautery was used to excise the tumors and the bases of the lesions were fulgurated.

Figure 1.

Cystoscopy revealed three polypoid masses, each protruding from a stalk.

3. Results

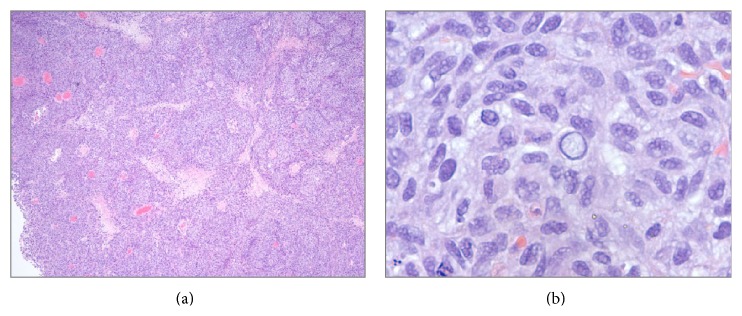

Histologic examination revealed diffuse hypercellular sheets and nests of basophilic medium to large tumor cells with high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, moderate nuclear pleomorphism, irregular nuclear contours, abundant intranuclear and cytoplasmic pseudoinclusions, vesicular chromatin, and occasional prominent nucleoli (Figure 2). Brisk mitotic activity was noted with atypical mitotic figures. Tumor cells were noted to engulf other tumor cells (tumor cannibalism). Numerous apoptotic bodies and karyorrhectic debris were present, along with patchy areas of geographic tumor necrosis with tumor cells palisading around necrotic foci. The sheets of tumor cells invaded into the muscularis propria of the bladder wall. There was no evidence of intracytoplasmic melanin pigmentation or pigment incontinence. Due to surface ulceration, no evidence of superficial urothelium was identified. Biopsy of the patient's previous skin lesion was not available for comparative review.

Figure 2.

(a) Sheets and nests of tumor cells interspersed with patchy areas of necrosis (hematoxylin-eosin, 40x). (b) The tumor cells have a moderate degree of nuclear pleomorphism and occasionally demonstrate intranuclear and cytoplasmic pseudoinclusions (hematoxylin-eosin, 400x).

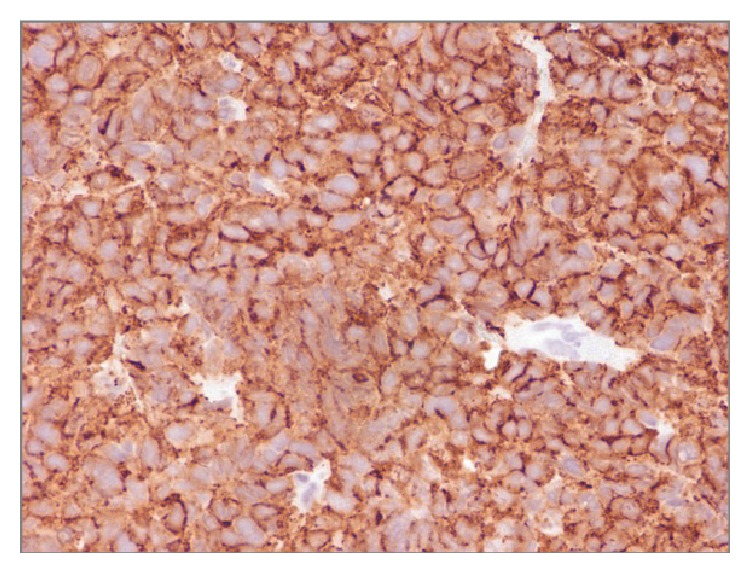

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) of the bladder lesion revealed diffuse positivity with Melan-A (Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA) and S100 protein (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) (Figure 3). Tumor cells did not stain with p63 (BioGenex Laboratories, San Ramon, CA) or cytokeratin 34BE12 (Enzo Life Sciences, New York, NY). A final histopathological diagnosis of metastatic malignant melanoma involving bladder mucosa was rendered.

Figure 3.

Tumor cells are strongly and diffusely positive for Melan-A.

4. Discussion

The presence of metastatic malignant melanoma within the urinary bladder is an exceedingly rare finding. A literature review by Efesoy and Cayan in 2011 states that there are less than ten cases reported in the last 30 years in the English literature [4]. Similarly, in 2014, Rishi et al. stated that there are “less than score of cases” [5]. This number is cited as slightly higher in a case report by Paterson et al. in which fourteen cases are listed [3]. We conducted a thorough PUBMED search and found that there are a total of twenty-three reported cases (Table 1). Patient age ranged from 28 to 84 years with a mean age of 56.5 years. Men were more commonly affected than women (M : F = 15 : 8). Not surprisingly, the most common primary site of disease was the skin. Sixteen cases had synchronous metastases of melanoma in other sites, five of which were considered “widespread.” The most common presenting symptom in bladder metastasis was hematuria, present in sixteen cases.

Table 1.

Cases of malignant melanoma metastatic to urinary bladder previously reported in the English literature.

| Author | Year | Age | Sex | Presenting symptom | Primary | Synchronous metastases | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weston and Smith [10] | 1964 | 69 | M | Urinary retention | Right lower eyelid | Widespread | None |

|

| |||||||

| Bartone [18] | 1964 | 70 | F | Hematuria | Left thumb | Lymph nodes, brain | Partial cystectomy |

|

| |||||||

| Amar [19] | 1964 | 33 | M | Hematuria | Maxillary | Anterior neck | Partial cystectomy |

|

| |||||||

| Meyer [9] | 1974 | 69 | M | None | Unknown | Widespread | Chemotherapy |

|

| |||||||

| Meyer [9] | 1974 | 60 | F | Hematuria | Skin, left arm | Unknown | Surgery |

|

| |||||||

| Meyer [9] | 1974 | 42 | M | Incidental | Skin, right upper back | Widespread | TURBT |

|

| |||||||

| Silverstein et al. [20] | 1974 | 56 | M | Hematuria | Axillary lymph nodes | Absent | BCG |

|

| |||||||

| Tolley et al. [21] | 1975 | 48 | F | Hematuria | Vulva | Absent | Radical cystectomy |

|

| |||||||

| Stein and Kendall [22] | 1984 | 50 | M | Hematuria | Left arm | Absent | TURBT + chemotherapy |

|

| |||||||

| Irisawa et al. [23] | 1987 | 77 | M | Occult blood | Eye | Diffuse | TURBT |

|

| |||||||

| Arapantoni-Dadioti et al. [24] | 1995 | 28 | F | Dysuria | Axillary lymph node | Skin (abdomen, limbs), lung, and brain | TURBT |

|

| |||||||

| Demirkesen et al. [25] | 2000 | 45 | F | Frequency, hematuria | Right heel | Widespread | Chemotherapy |

|

| |||||||

| López et al. [26] | 2002 | 75 | M | Hematuria, lower urinary symptoms | Skin, scapula | Unknown | Cystectomy |

|

| |||||||

| Lee et al. [27] | 2003 | 46 | M | Hematuria | Skin, back | Lungs, liver, and mesenteric lymph nodes | Removed tumor and then IL-2 therapy |

|

| |||||||

| Fink et al. [28] | 2003 | 38 | M | Hematuria | Skin, left upper leg | Tonsils, cervical lymph nodes, esophagus, stomach, and skin | Embolization of nutrient vessels |

|

| |||||||

| Maeda et al. [29] | 2008 | 65 | M | Hematuria, urinary obstruction | Skin, foot | Unknown | TURBT |

|

| |||||||

| Nohara et al. [30] | 2009 | 62 | M | Hematuria | Skin, breast | Lymph nodes | Unknown |

|

| |||||||

| Efesoy and Cayan [4] | 2011 | 60 | F | Hematuria, weight loss | Skin, right middle finger | Brain, lung, and retroperitoneal and pelvic lymph nodes | TURBT |

|

| |||||||

| Nair et al. [6] | 2011 | 54 | M | Hematuria | Conjunctiva | Widespread | TURBT, chemo, and radiation for brain metastases |

|

| |||||||

| Charfi et al. [31] | 2012 | 54 | M | Unknown | Esophagus | Lumbar lymph nodes | Unknown |

|

| |||||||

| Paterson et al. [3] | 2012 | 84 | M | Rectal bleeding | Skin, upper back | Lungs | |

|

| |||||||

| Ikeda et al. [32] | 2013 | 54 | F | Hematuria | Skin, leg | Absent | TURBT |

|

| |||||||

| Rishi et al. [5] | 2014 | 61 | F | Dysuria, hematuria | Skin, mid-back | Brain, lung, and skin | Tumor resection, brain radiotherapy, and temozolomide |

|

| |||||||

| Meunier (current case) | 2014 | 55 | F | Hematuria | Skin, thigh | Liver, spleen, and lung | Ipilimumab + anti-PD-1 immunotherapy trial |

While the most common imaging modality for bladder tumors is magnetic resonance imaging, cystoscopy is useful in its ability to visualize the bladder mucosa. However, there are cases in which the mucosa is uninvolved and the metastatic melanoma only involves the bladder wall [6]. Of all the cases published to date, synchronous metastases were present in all but four patients. Unfortunately, the long term followup for the patients without synchronous metastases was not available for comparison with those having synchronous disease.

In cases where the clinical history of primary melanoma is noted, the diagnosis of bladder metastases is often straightforward and can be confirmed by immunohistochemical stains. However, in the absence of a clinical history of melanoma, other lesions with an infiltrative growth pattern and similar cytomorphology may be considered. The possible list of differential diagnoses includes high grade urothelial carcinoma, prostatic carcinoma in male, Müllerian carcinomas in female, lung carcinoma, breast carcinoma, and rare entities like paraganglioma and sarcomatoid carcinoma.

When faced with this diagnostic challenge, there are certain morphological features that can be helpful in differentiating metastatic melanoma from high grade urothelial carcinoma. Malignant melanoma usually presents as a nodule devoid of mucosal excrescences and papillary fronds. The overlying urothelium is mostly unremarkable without any in situ components. In general, the absence of a superficial urothelial lesion overlying a poorly differentiated tumor is an important clue to secondary bladder neoplasia, including metastatic melanoma [5]. The presence of intramucosal atypical melanocytes has been reported in primary bladder melanomas and is considered a prerequisite finding for the diagnosis of primary bladder origin [7]; however, there is no report of such lesions in secondary bladder melanoma.

Tumor cells in melanoma are predominantly comprised of epithelioid cells with rare spindle cell morphology. They reveal macronuclei with marked variation in nuclear size and shape. Nuclei are hyperchromatic with prominent large eosinophilic nucleoli. A helpful feature is the conspicuous presence of intranuclear inclusions. The stroma surrounding melanoma is usually desmoplastic and inflamed, with melanophage aggregation. Intracytoplasmic pigments are useful when present. Atypical mitoses and lymphovascular invasion can also point to secondary bladder tumors including melanoma. It is noteworthy that none of the above-mentioned morphological findings are pathognomonic and a multimodal approach should be considered when confronting a suspicious secondary bladder tumor. The diagnosis can be confirmed using a panel of IHC (vide infra).

Urothelial carcinoma on the other hand is usually associated with a papillary or flat carcinoma in situ (CIS) component on the surface of the lesion that is continuous with the invasive component. Urothelial lesions commonly show glandular or squamous differentiation without cytoplasmic pigmentation or pigment incontinence around tumor nests. IHC staining for high molecular weight cytokeratin (34BE12 and CK5/6), p63, uroplakin, thrombomodulin, and GATA3 supports urothelial origin.

Prostate adenocarcinoma in males lacks cellular pleomorphism. Tumor cells are typically uniform and form glandular and cribriform arrangements. There is generally a high tendency for invasion into perineural spaces in the tumor. IHC staining for prostate-specific antigen (PSA), prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA), alpha methylacyl-CoA racemase (AMACR), and prostein (P501s) can be very helpful in differential diagnosis.

Metastatic Müllerian tumors are diverse and, based on the subtype and organ of origin, can show variable morphologies. Some variants like high grade serous carcinoma can show marked cellular pleomorphism and extension beyond the organ of origin. Such tumors show micropapillary clusters with psammomatous calcifications. These tumors are usually cytokeratin positive and based on the site of origin can express PAX8, estrogen (ER), and progesterone (PR) receptors.

Breast carcinoma can be seen metastasizing into bladder and other pelvic organs. Arrangement of tumor cells in single file, discohesive tumor cells, and intracytoplasmic vacuoles can often be seen in metastasizing lobular breast carcinoma. However, some other carcinomas like lung may not show any specific morphological features to suggest a secondary tumor. In such situations, IHC is very helpful in the differential diagnosis. In the case of breast cancer, ER, PR, GATA3, and mammaglobin can be helpful, while TTF1 and napsin-A can point toward lung adenocarcinoma.

Paraganglioma of the bladder can also mimic melanoma. Occasionally these tumors cause prominent clinical symptoms. Morphologically, bladder paraganglioma is composed of a monomorphic cell population with or without cytoplasmic clearing and rare mitosis without atypical forms. IHC for chromogranin-A and synaptophysin is helpful in the diagnosis [8].

Rishi et al. suggest that metastatic melanoma often has nonrefractile green-brown pigment on gross examination [5]. In the available literature, only five case reports have noted the presence of grossly pigmented dark blue or black lesions on cystoscopy [3, 9–11]. The current case did not show any evidence of discoloration within the lesion. The histologic presence of pigment within lesional cells or surrounding histiocytes should prompt the pathologist to consider metastatic melanoma in the differential diagnosis.

Melanosis, both with and without atypia, has been reported in about a dozen cases in the literature [12]. Although melanosis usually occurs independently without any associated or adjacent lesions, it may be seen with other malignancies. One must keep in mind that the presence of melanosis within the bladder does not necessarily confer the diagnosis of melanoma. There are two reported cases of melanosis with subsequent development of urothelial carcinoma and one reported case of melanosis with subsequent development of multifocal malignant melanoma [13–15].

Sarcomatoid carcinoma may mimic metastatic melanoma with spindle cell morphology. The cells of sarcomatoid carcinoma are often large, spindled, and pleomorphic and may appear similar to the pleomorphic melanocytes of melanoma. However, the presence of heterologous elements such as cartilage or bone should point towards a diagnosis of sarcomatoid carcinoma. To confirm the diagnosis, areas of the tumor with epithelial differentiation should be cytokeratin positive, whereas melanoma will be negative.

To confirm the diagnosis of metastatic malignant melanoma, IHC is invaluable. S100 protein is a sensitive but not very specific marker and should be confirmed by more specific markers including Melan-A, HMB45, and MITF. One must be aware of the variable expression of melanoma markers in metastatic melanoma. The heterogeneity of melanoma associated antigens can even be seen within a single lesion. Therefore, we recommend the use of more than one melanoma marker. Cytokeratin expression, on the other hand, has been reported in up to 2% of melanomas [16]; therefore, this marker can be reliably used to rule out other carcinomas.

When confronting a malignant melanoma of the bladder in the absence of any clinical evidence of a primary lesion, one must keep primary malignant melanoma of the bladder within the differential diagnosis. Primary malignant melanoma of the genitourinary tract is very rare and most frequently involves the distal urethra [17], with less than thirty cases reported in the literature. In addition, one must be wary of collision tumors in which a melanoma metastasizes to a primary bladder tumor. Although uncommon, there is a single case report of a melanoma metastasizing to a preexisting urothelial carcinoma [11].

In summary, to date there are 24 known cases of malignant melanoma metastatic to the urinary bladder. As “the great mimicker,” melanoma can take on various histologic appearances and it is important to keep this entity in the differential diagnosis of high grade infiltrative urothelial lesions without a papillary or in situ component. Immunohistochemical stains and a thorough clinical history and examination can provide further assurance in making the diagnosis.

Abbreviations

- IHC:

Immunohistochemistry

- CIS:

Carcinoma in situ

- TURBT:

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Authors' Contribution

Dr. Gyan Pareek was the urologist of the patient, provided the tumor material, and provided clinical history. Dr. Ali Amin signed out the case and reviewed and edited the paper. Dr. Rashna Meunier wrote the paper and took the microscopic photographs.

References

- 1.Das Gupta T., Brasfield R. Metastatic melanoma. A clinicopathological study. Cancer. 1964;17:1323–1339. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196410)17:1060;1323::aid-cncr282017101562;3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates A. W., Baithun S. I. Secondary neoplasms of the bladder are histological mimics of nontransitional cell primary tumours: clinicopathological and histological features of 282 cases. Histopathology. 2000;36(1):32–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2000.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paterson A., Sut M., Kaul A., et al. Metastatic malignant melanoma of the urinary bladder: case report and literature review. Central European Journal of Urology. 2012;65(4):232–234. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2012.04.art13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Efesoy O., Cayan S. Bladder metastasis of malignant melanoma: a case report and review of literature. Medical Oncology. 2011;28(supplement 1):S667–S669. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9730-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rishi A., Anderson T. A., Kirschenbaum A. M., Unger P. D. Metastatic malignant melanoma to urinary bladder: a potential pitfall for high-grade urothelial carcinoma. International Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2014;22(4):347–351. doi: 10.1177/1066896913492199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nair B. C. J., Williams N. C., Cui C., et al. Conjunctival melanoma: bladder and upper urinary tract metastases. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011;29(9):e216–e219. doi: 10.1200/jco.2010.32.3584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ainsworth A. M., Clark W. H., Mastrangelo M., Conger K. B. Primary malignant melanoma of the urinary bladder. Cancer. 1976;37(4):1928–1936. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197604)37:4<1928::aid-cncr2820370444>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou M., Epstein J. I., Young R. H. Paraganglioma of the Urinary Bladder: A Lesion That May Be Misdiagnosed as Urothelial Carcinoma in Transurethral Resection Specimens. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 2004;28(1):94–100. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200401000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyer J. E. Metastatic melanoma of the urinary bladder. Cancer. 1974;34(5):1822–1824. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197411)34:560;1822::aid-cncr282034053362;3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weston P. A., Smith B. J. Metastatic melanoma in the bladder and urethra. The British Journal of Surgery. 1964;51:78–79. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800510115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arapantoni-Dadioti P., Panayiotides J., Kalkandi P., Christodoulou C., Delides G. S. Metastasis of malignant melanoma to a transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 1995;21(1):92–93. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(05)80079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willys C. B., Winkle D. C., Kerr K. M. Urinary bladder melanosis: case report of a rare mucosal lesion. Pathology. 2011;43(2):164–166. doi: 10.1097/pat.0b013e32834274ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanborn S. L., MacLennan G., Cooney M. M., Zhou M., Ponsky L. E. High-grade transitional cell carcinoma and melanosis of urinary bladder: case report and review of the literature. Urology. 2009;73(4):928.e13–928.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harikrishnan J. A., Chilka S., Jain S. Urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma and melanosis of the bladder: a case report and review of the literature. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2012;94(4):e152–e154. doi: 10.1308/003588412x13171221589135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerley S. W., Blute M. L., Keeney G. L. Multifocal malignant melanoma arising in vesicovaginal melanosis. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine. 1991;115(9):950–952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King R., Busam K., Rosai J. Metastatic malignant melanoma resembling malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor: report of 16 cases. American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 1999;23(12):1499–1505. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199912000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Venyo A. K.-G. Melanoma of the urinary bladder: a review of the literature. Surgery Research and Practice. 2014;2014:13. doi: 10.1155/2014/605802.605802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bartone F. F. Metastatic melanoma of the bladder. Journal of Urology. 1964;91:151–155. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)64079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amar A. D. Metastatic melanoma of the bladder. The Journal of Urology. 1964;92:198–200. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)63923-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silverstein M. J., DeKernion J., Morton D. L. Malignant melanoma metastatic to the bladder. Regression following intratumor injection of BCG vaccine. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1974;229(6):p. 688. doi: 10.1001/jama.229.6.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tolley D. A., Castro J. E., Anseli I. D. Malignant metastatic melanoma of the bladder. British Journal of Clinical Practice. 1975;29(10):276–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stein B. S., Kendall A. R. Malignant melanoma of the genitourinary tract. The Journal of Urology. 1984;132(5):859–868. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49927-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irisawa C., Onmura Y., Matsushita S. Metastatic malignant melanoma of the urinary bladder: a case report. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1987;33(3):424–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arapantoni-Dadioti P., Panayiotides J., Kalkandi P., Christodoulou C., Delides G. S. Metastasis of malignant melanoma to a transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. European Journal of Surgical Oncology. 1995;21(1):92–93. doi: 10.1016/S0748-7983(05)80079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demirkesen O., Yaycioglu O., Uygun N., Demir G., Yalcin V. A case of metastatic malignant melanoma presenting with hematuria. Urologia Internationalis. 2000;64(2):118–120. doi: 10.1159/000030506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.López V. M., García R. A.-V., Arqués M. S., González P. C. Bladder metastasis of malignant melanoma: report of a case. Archivos Españoles de Urología. 10. Vol. 55. 1277; 2002. (1279). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee C. S., Komenaka I. K., Hurst-Wicker K. S., Deraffele G., Mitcham J., Kaufman H. L. Management of metastatic malignant melanoma of the bladder. Urology. 2003;62(2):p. 351. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00354-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fink W., Zimpfer A., Ugurel S. Mucosal metastases in malignant melanoma. Onkologie. 2003;26(3):249–251. doi: 10.1159/000071620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maeda T., Uchida Y., Kouda T., et al. Metastatic malignant melanoma of the urinary bladder presenting with hematuria: a case report. Acta Urologica Japonica. 2008;54(12):787–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nohara T., Sakai A., Fuse H., Imamura Y. Metastatic malignant melanoma of the urinary bladder: a case report. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi. 2009;100(7):707–711. doi: 10.5980/jpnjurol.100.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charfi S., Ellouze S., Mnif H., Amouri A., Khabir A., Sellami-Boudawara T. Plasmacytoid melanoma of the urinary bladder and lymph nodes with immunohistochemical expression of plasma cell markers revealing primary esophageal melanoma. Case Reports in Pathology. 2012;2012:5. doi: 10.1155/2012/916256.916256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ikeda A., Miyagawa T., Kurobe M., et al. Case of metastatic malignant melanoma of the urinary bladder. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2013;59(9):579–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]