Abstract

Background

The number of individual patient data meta-analyses published is very low especially in surgical domains. Our aim was to assess the feasibility of individual patient data (IPD) meta-analyses in orthopaedic surgery by determining whether trialists agree to send IPD for eligible trials.

Methods

We performed a literature search to identify relevant research questions in orthopaedic surgery. For each question, we developed a protocol synopsis for an IPD meta-analysis and identified all related randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with results published since 2000. Corresponding authors of these RCTs were sent personalized emails that presented a project for an IPD meta-analysis corresponding to one of the research questions, with a link to the protocol synopsis, and asking for IPD from their RCT. We guaranteed patient confidentiality and secure data storage, and offered co-authorship and coverage of costs related to extraction.

Results

We identified 38 research questions and 273 RCTs related to these questions. We could contact 217 of the 273 corresponding authors (79 %; 56 had unavailable or non-functional email addresses) and received 68/273 responses (25 %): 21 authors refused to share IPD, 10 stated that our request was under consideration and 37 agreed to send IPD. Four corresponding authors required authorship and three others asked for financial support to send the IPD. Overall, we could obtain IPD for 5,110 of 33,602 eligible patients (15 %). Among the 38 research questions, only one IPD meta-analysis could be potentially initiated because we could receive IPD for more than 50 % of participants.

Conclusion

The present study illustrates the difficulties in initiating IPD meta-analyses in orthopaedic surgery. Significant efforts must be made to improve data sharing.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12916-015-0376-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Individual patient data, Meta-analysis, Data sharing, Randomized controlled trials, Surgery

Background

Individual patient data (IPD) meta-analyses (MAs) are generally considered to provide the highest level of evidence [1]. IPD MAs have theoretical advantages over MAs of aggregated data because the use of original source material allows for standardizing analyses across studies and trial results are obtained directly, independent of the quality of reporting [1–3]. Nevertheless, the number of IPD MAs published is very low, with a mean of 49 IPD MAs published each year between 2005 and 2009 [1] as compared with thousands of MAs of aggregated data. The number of IPD MAs is particularly low in surgical domains. In a recent systematic review of IPD MAs, 22 of the 583 IPD MAs published between 2005 and 2012 assessed surgical interventions [4].

The main barrier to performing an IPD MA is the lack of data sharing by researchers. Many researchers are reluctant to share IPD because of patient protection, ownership [5], or the cost [1, 6] to ensure confidentiality and anonymity of patients and archiving the data [1, 7]. Moreover, additional pitfalls, such as the availability of data [8] with practical difficulties related to data sharing many years after the completion of a trial, potentiate the risk of an incomplete data sharing process. There is an evolution in ideas and thinking about data sharing among researchers [9–16], funders [17–19], the Cochrane collaboration [20] and journals [21–25]. However, to our knowledge, no clear data sharing policy has been established by orthopaedic journals or institutions. Thus, data sharing in orthopaedic surgery relies mainly on cooperation from the clinical trialists who generate and maintain these data.

In the present study, we aimed to assess the feasibility of performing IPD MAs in orthopaedic surgery, testing whether trialists agree to share IPD for IPD MAs. We also assessed the conditions that allow for such data sharing.

Methods

In a first step, we identified orthopaedic clinical research questions that could be evaluated with IPD MAs. Then, using personalized emails, we systematically contacted corresponding authors of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) related to those clinical questions and asked them whether they would agree to share the IPD from their trials for an MA.

Identification of clinical research questions in orthopaedic surgery

To identify relevant clinical research questions in orthopaedic surgery that could justify an IPD MA, we relied on questions assessed in recently published systematic reviews with MAs of aggregated data.

Search of systematic reviews with MAs of aggregated data assessing orthopaedic surgical procedures

On 6 April 2014, we searched MEDLINE via PubMed for systematic reviews published between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2013, using the search equation reported in Additional file 1. This search equation combined MESH terms related to: orthopaedics and free-text words corresponding to the main orthopaedic surgical procedures; publication type and free-text words corresponding tosystematic reviews and MAs; and a modified version of the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy to identify RCTs. In addition, we performed a search of the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Orthopaedics and Trauma and Rheumatology) to identify Cochrane systematic reviews assessing an orthopaedic surgical procedure and published in 2013. The search results were pooled and duplicate records were removed.

Selection of systematic reviews

The title, abstract and full text, when necessary, of all identified references were screened by two authors (BV and PB). We included systematic reviews written in English or French and published in 2013 that assessed an orthopaedic surgical procedure, with no restriction on comparator (usual care, placebo, conservative intervention, pharmacological treatment or other surgical implant or procedure), and including an MA of aggregated data based on two or more RCTs. Systematic reviews and MAs that were withdrawn were excluded, as were those for which the full text was not available.

Extraction of clinical research questions from the systematic reviews

Two reviewers (BV and PB) independently extracted all elements of the clinical research question assessed from the full text of the systematic reviews by using the Population, Intervention tested, Comparator and primary Outcomes (PICO) acronym [26]. Then, all clinical questions were classified by anatomical region (e.g., shoulder) and surgical procedure tested (e.g., arthroplasty) to identify any potentially redundant research questions.

Development of protocol synopsis of IPD MA for each clinical research question

For each clinical research question, we developed a standardized protocol synopsis for an IPD MA, with the background and objectives sections derived from the corresponding systematic review with MA of aggregated data and the methods section based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [27]. An example of a protocol synopsis is presented in Additional file 2.

Identification of RCTs relevant to the clinical research questions

We identified all RCTs included in the systematic reviews with MA of aggregated data for the clinical research questions. All RCTs were selected provided they were written in English or French and results were published since 2000, because for trials with results published before 2000, we anticipated difficulties in contacting corresponding authors and obtaining IPD from these trials. Non-randomized studies and quasi-RCTs were excluded, as were RCTs not indexed in MEDLINE. If corresponding authors were involved in several RCTs corresponding to different clinical research questions, we contacted them for only one clinical question chosen at random. Only the RCTs corresponding to this clinical question were selected.

Extraction of characteristics of the selected RCTs

Using a pre-tested standardized form, we extracted the following characteristics from the full text and online Additional files, as well as journal websites:

Corresponding author: name and email address of the corresponding author. When the email address was not available in the article or not functional, the name was entered in PubMed to search for another study published by the author for which the email address was reported. We also screened the website of the author’s institution to search for an email address.

Characteristics of the trial: publication date, whether the trial was a single-centre or multicentre trial, location of the study (Africa, Asia, Australia and New Zealand, Europe, North America, South America) and funding source (public, private, both public and private, not reported). The geographic location of the corresponding author’s affiliated institution was used to define the location of the study when the study location was not reported or when the RCT was an international multicentre study. We also extracted the number of patients randomized in each RCT.

Characteristics of the journal in which the RCT was published: name of the journal, whether it was specialized or general and its impact factor. We classified journals according to whether they were in the 10 highest impact factors for a medical condition according to the Journal Citation Reports. We also recorded whether the journal had a data sharing policy and, if so, whether data sharing was a mandatory condition to publish.

Contacting the corresponding authors of identified RCTs

Corresponding authors of each RCT were contacted by personalized email to participate in a specific IPD MA project and to provide IPD from their RCT. The email stated that the French Cochrane Centre aimed to initiate collaboration among trialists to perform IPD MAs on important orthopaedic topics and that the first project had as an objective the clinical research question for which the RCT was eligible. We guaranteed protection of patient data and secure storage of datasets. We also systematically asked whether the corresponding author or another colleague wanted to be a co-author of the published IPD MA and whether we should cover costs related to data extraction. The emails were personalized for each trialist and clinical research question, with inclusion of the name of the corresponding author, title, year of publication and journal in which the author’s trial was published, as well as the objective of the IPD MA and a link to the protocol synopsis of the IPD MA corresponding to the research question assessed. The subject of the email was ‘Your article ‘Trial title’, published in ‘Journal’ on ‘Year of publication”. Emails were sent using a dedicated Cochrane address and were signed by an academic orthopaedic surgeon on behalf of the French Cochrane Centre, the French Equator Centre and the Inserm Research Centre U1153. An example of the email sent is available in Additional file 3. Two similar reminders were sent to the authors 15 and 30 days after the first email if we did not receive a response to the initial request.

It has to be noted that our hypothesis was that the rate of positive answers would be low but we expected to be able to perform several IPD meta-analyses as part of a PhD program for the clinical questions for which we would have received a sufficient number of positive answers.

Statistical analyses

Characteristics of systematic reviews and RCTs were described along with the number and percentage for categorical variables. We compared characteristics of trials and journals for trials for which we had a positive response and a negative or no response to our request for data sharing by two-sided chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, with a type I error level of 0.05. We excluded from this comparison authors who responded that our request was under consideration. Data were analyzed by using R version 2.13.1 [28].

Results

Identification of clinical research questions in orthopaedic surgery

Additional file 4 describes the flow of the selection of systematic reviews. Briefly, we screened 418 records and selected 63 systematic reviews with MA of aggregated data corresponding to 38 different clinical research questions described in Table 1. The main characteristics of the 63 systematic reviews are presented in Additional file 5.

Table 1.

Description of the 38 identified clinical research questions in orthopaedics

| Anatomic area | Pathology | Intervention | Comparator | Primary outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shoulder | Rotator cuff tears | Arthroscopic double-row repair | Arthroscopic single-row repair | Function |

| Midshaft clavicular fractures | Surgical treatment | Non-operative treatment | Function | |

| Proximal humeral fractures in older patients | Surgical treatment | Non-operative treatment | Function | |

| Osteoarthritis | Total shoulder arthroplasty | Shoulder hemiarthroplasty | Function | |

| Arm | Humeral shaft fracture | Intramedullary nail | Internal fixation with plate | Function |

| Elbow | Supracondylar fractures in children | Lateral pin fixation | Crossed pin fixation | Function, iatrogenic ulnar nerve injury |

| Wrist | Distal radial fractures | Anterior ORIF | External fixation | Function, radiographic consolidation |

| Distal radial fractures | Anterior ORIF | Posterior ORIF | Function, radiographic consolidation | |

| Hip | Osteoarthritis | Minimally invasive approach | Standard approach | Function, revision rate |

| Osteoarthritis | No wound drainage after THA | Wound drainage after THA | Function, wound infection, wound haematoma | |

| Osteoarthritis | Navigated THA | Conventional arthroplasty | Function, revision rate, dislocation | |

| Intracapsular fractures | Uncemented hemiarthroplasty | Cemented hemiarthroplasty | Mortality, function, pain at 1 year, revision rate | |

| Osteoarthritis | Uncemented THA | Cemented THA | Function, revision rate | |

| Hip and knee | Osteoarthritis | Antibiotic impregnated cement | Non-antibiotic-impregnated cement | Postoperative infection rate |

| Knee | Osteoarthritis | TKA, minimally invasive approach | Standard approach for TKA | Function |

| Osteoarthritis | Mobile-bearing TKA | Fixed-bearing TKA | Function, reoperation rate | |

| Osteoarthritis | TKA without tourniquet | TKA under tourniquet | Function, total blood loss | |

| Osteoarthritis | Drainage clamping after TKA | TKA conventional drainage | Hb loss, transfusion, function | |

| Osteoarthritis | No patellar resurfacing in TKA | Patellar resurfacing in TKA | Function, reoperation rate, anterior knee pain | |

| Osteoarthritis | PCL-retaining TKA | Posterior-stabilized TKA | Function, reoperation rate | |

| Osteoarthritis | TKA electrocautery of patella | No electrocautery of patella | Function, reoperation rate, anterior knee pain | |

| Osteoarthritis | Gender-specific TKA | Unisex TKA | Function, reoperation rate, pain, | |

| Osteoarthritis | Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty | Tibial osteotomy | Function, reoperation rate | |

| ACL tears | Double-bundle ACL reconstruction | Single-bundle ACL reconstruction | Function, reoperation rate | |

| ACL tears | Early ACL reconstruction | Delayed ACL reconstruction | Function, reoperation rate | |

| ACL tears | Allograft ACL reconstruction | Autograft ACL reconstruction | Function, reoperation rate | |

| Arthroscopic procedures | Arthroscopic procedures without tourniquet | Arthroscopic procedures using tourniquet | Function | |

| Leg | Distal tibial shaft fractures | Intramedullary nailing | Internal fixation with plate | Function, nonunion and malunion rate |

| Tibial shaft fractures | Reamed intramedullary nailing | Unreamed intramedullary nailing | Function, nonunion and malunion rate | |

| Ankle | Acute Achilles tendon rupture | Early weight bearing | Delayed weight bearing | Function, rerupture rate |

| Ankle fractures | Surgical treatment, biodegradable implants | Surgical treatment, conventional implants | Function, nonunion and malunion rate | |

| Foot | Calcaneal fractures | Surgical treatment | Non-operative treatment | Function, chronic pain |

| Spine | Cervical disc disease | Cervical disc arthroplasty | Cervical interbody fusion | Function, pain |

| Osteoporotic vertebral fractures | Percutaneous vertebroplasty | Conservative treatment | Function, pain, quality of life | |

| Osteoporotic vertebral fractures | Bilateral pedicular kyphoplasty | Unilateral pedicular kyphoplasty | Function, pain, quality of life | |

| Lumbar disc disease | Lumbar disc arthroplasty | Lumbar interbody fusion | Function, pain | |

| Thoracolumbar burst fractures | Fracture fixation associated to fusion | Fracture fixation alone | Function, pain, quality of life | |

| Thoracolumbar burst fractures | Surgical treatment | Conservative treatment | Function, pain, quality of life |

ACL: Anterior cruciate ligament; Hb: Haemoglobin; ORIF: Open reduction and internal fixation; PCL: Posterior cruciate ligament; THA: Total hip arthroplasty; TKA: Total knee arthroplasty

Identification of RCTs corresponding to the clinical research questions

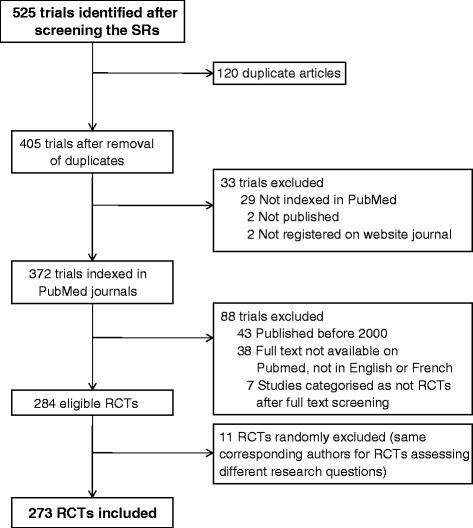

From the full text of these 63 systematic reviews, we identified 525 trials and selected 284 eligible trials 11 were further excluded because the corresponding authors were involved in several RCTs assessing different research questions, so our study was based on 273 RCTs (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the selection of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) corresponding to the 38 clinical research questions

Characteristics of the selected RCTs

The main characteristics of the RCTs are summarized in Table 2. Briefly, 183 RCTs (67 %) were single-centre trials; 60 (22 %) were multicentre trials, with unknown status for 30 trials (11 %). Most of the trials took place in Europe, North America and Asia (39 %, 29 % and 29 %, respectively). The funding source was reported for 53 % of RCTs and was public for 35 %. Forty-two percent of RCTs were published between 2010 and 2013. Most of the RCTs (95 %) were published in specialized journals. Only 32 (12 %) were published in journals that had a clearly described data sharing policy.

Table 2.

General characteristics of the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) related to the clinical research questions (n = 273)

| Characteristics | Number of RCTs (%) |

|---|---|

| (n = 273) | |

| Trial characteristics | |

| Study design | |

| Single-centre | 183 (67 %) |

| Multicentre | 60 (22 %) |

| Not reported | 30 (11 %) |

| Location | |

| Europe | 106 (39 %) |

| North America | 80 (29 %) |

| Asia | 78 (29 %) |

| Australia and New Zealand | 9 (3 %) |

| Funding | |

| Public | 96 (35 %) |

| Private | 49 (18 %) |

| Not reported | 128 (47 %) |

| Year of publication | |

| 2000–2004 | 46 (17 %) |

| 2005–2009 | 112 (41 %) |

| 2010–2013 | 115 (42 %) |

| Journal of publication characteristics | |

| Type of journal | |

| Specialized | 260 (95 %) |

| Generalist | 13 (5 %) |

| Top 10 impact factor of each specialty | |

| No | 156 (57 %) |

| Yes | 117 (43 %) |

| Journal data sharing policies | |

| No policy | 241 (88 %) |

| Incentive measures | 24 (9 %) |

| Mandatory | 8 (3 %) |

Data sharing request

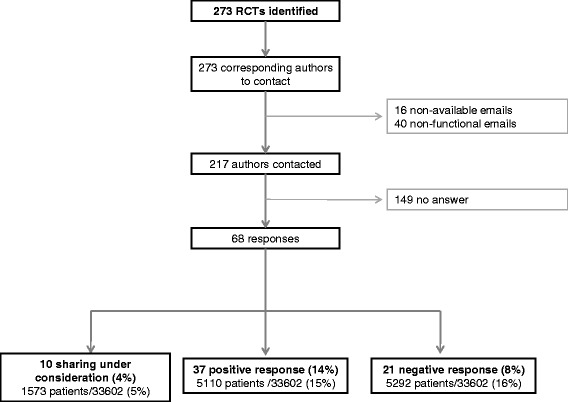

The email address of the corresponding author was available and functional for 217 of the 273 RCTs (79 %). We received 68 responses (Fig. 2). In total, 37 authors, corresponding to 14 % of the RCTs, agreed to send IPD: 30 without any conditions, four requiring co-authorship and three asking for financial support to send the IPD. Ten additional authors said that our request was under evaluation by the research team or sponsor and 21 authors refused to participate and to send IPD. Authors who refused to send IPD did so because of no access to the data (n = 8), ethical concerns (n = 5), lack of time (n = 5) and no reason (n = 3).

Fig. 2.

Flow chart of data sharing request process

Feasibility of IPD MAs in orthopaedic surgery

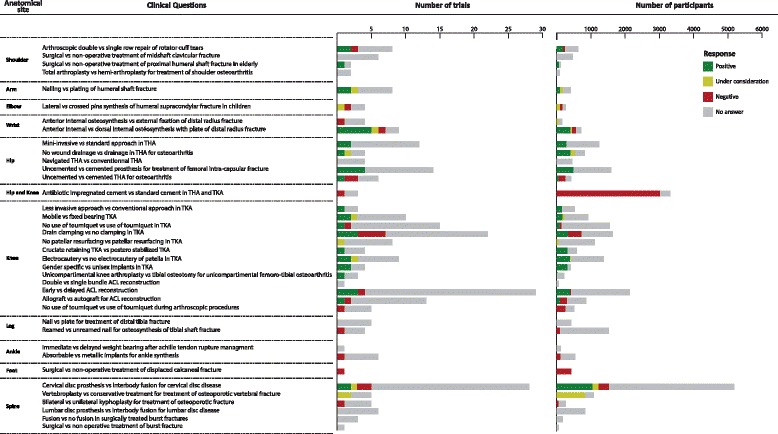

Overall, we obtained agreement to receive IPD for 5,110 of 33,602 eligible patients (15 %). We obtained agreement to receive IPD for more than 50 % of participants for only one of the 38 clinical research questions. This question concerned comparing external fixation and internal anterior fixation for distal radial fracture with 399 participants (five studies) among 712 eligible (nine studies) (56 %) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Distribution of answers to request for data sharing by clinical questions. ACL: Anterior cruciate ligament; THA: Total hip arthroplasty; TKA: Total knee arthroplasty

Comparison of characteristics of RCTs with a positive response and negative or no response to the request for data sharing

We did not identify any factor significantly associated with a positive response to our request for data sharing (Table 3). We received a positive response for 19/176 (11 %) single-centre trials, 11/57 (19 %) multicentre trials (P = 0.07), 20/117 (17 %) trials published in the top 10 journals (with the highest impact factor) and 17/146 (12 %) trials not published in the top 10 journals (P = 0.21). We received a positive response for 2/30 (7 %) trials published in journals with data sharing policies and 35/233 (15 %) trials published in journals without data sharing policies (P = 0.27).

Table 3.

Characteristics of RCTs with a positive response and negative or no response to the request for data sharing

| Characteristics | Data sharing requesta (n = 263) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | |||

| Positive response | Negative or no response | ||

| 37 (14%) | 226 (86%) | ||

| RCT characteristics | |||

| Study design | 0.07 | ||

| Single-centre (n = 176) | 19 (11%) | 157 (89%) | |

| Multicentre (n = 57) | 11 (19%) | 46 (81%) | |

| Not reported (n = 30) | 7 (23%) | 23 (77%) | |

| Location | 0.11 | ||

| Europe (n = 105) | 20 (19%) | 85 (81%) | |

| North America (n = 71) | 9 (13%) | 62 (87%) | |

| Asia (n = 78) | 6 (8%) | 72 (92%) | |

| Australia and New Zealand (n = 9) | 2 (22%) | 7 (78%) | |

| Funding | 0.19 | ||

| Public (n = 91) | 8 (9%) | 83 (91%) | |

| Privateb (n = 45) | 7 (16%) | 38 (84%) | |

| No response (n = 127) | 22 (17%) | 105 (83%) | |

| Year of publication | 0.57 | ||

| 2000–2004 (n = 44) | 4 (9%) | 40 (91%) | |

| 2005–2009 (n = 109) | 16 (15%) | 93 (85%) | |

| 2010–2013 (n = 110) | 17 (15%) | 93 (85%) | |

| Journal of publication characteristics | |||

| Journal of publication | 0.68 | ||

| Specialized (n = 251) | 35 (14%) | 216 (86%) | |

| Generalist (n = 12) | 2 (17%) | 10 (83%) | |

| Journal data sharing policies | 0.27 | ||

| Yes (support or mandatory) (n = 30) | 2 (7%) | 28 (93%) | |

| No (n = 233) | 35 (15%) | 198 (85%) | |

| Top 10 impact factor in each specialty | 0.21 | ||

| Yes (n = 117) | 20 (17%) | 97 (83%) | |

| No (n = 146) | 17 (12%) | 129 (88%) | |

aTen trials excluded because our request was being evaluated by the research team or sponsor at the time of statistical analysis; btotal number (n = ) used for calculating the percentage

Discussion

In this study, we requested IPD from corresponding authors for 273 RCTs in order to perform 38 IPD MAs covering different orthopaedic clinical research questions. Our results highlight the difficulty in performing IPD MAs. We could contact only 79 % of the identified corresponding authors despite additional searches on PubMed and the website for the author’s affiliation. The response rate was only 25 % (68/273 authors), with only 14 % (37/273) agreeing to participate in the IPD MA project. Because of this low rate of participation, only one IPD MA among the 38 planned could be potentially initiated.

Strengths and weaknesses

To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first to assess the feasibility of performing a large number of IPD MAs in real conditions. We had a pragmatic approach in adopting the point of view of researchers willing to initiate IPD MAs. Emails were personalized to each trialist and to each research question, with the protocol synopsis corresponding to the specific clinical question provided. We focused on orthopaedics because the number of clinical trials performed in this field is low [29–31] as compared with other specialties, so cooperation of trialists and data sharing are crucial to provide high-level evidence regarding the efficacy of interventions.

Some potential limitations should be discussed. We attempted to contact corresponding authors by email only. The rate of response could have been higher if we had contacted authors by telephone or postal mail. Also, it could have been higher with the collaboration of learned societies. We were able to contact only 79 % of investigators because of invalid email addresses, which can be explained by their moving to another institution. Author identification initiatives and online research profiles such as ResearchGate could help identify contact information of investigators [32]. The positive responses we received were an agreement to share IPD, but with no guarantee to finally obtain the IPD, so we may have overestimated the real number of datasets available for our IPD MA projects. Finally, Hannink et al. [4] identified an IPD MA published in 2011 assessing a question close to one of our 38 questions, which may explain the lack of positive response for this question [33].

Comparison with other studies

Some authors previously surveyed trialists’ opinions on data sharing, with most respondents in favour of sharing IPD [34, 35]. The difference from our results may be due to the fact that surveyed trialists were corresponding authors of trials recently published in general journals with the highest impact factor [34], some of these journals having adopted strong data sharing policies [22]. Also, our pragmatic approach may explain the difference. There is probably a gap between favouring data sharing and actually sending the IPD. There are some rare examples concerning a particular case reporting the difficulties encountered in obtaining IPD [36–39] including for performing IPD MAs [38, 39]. Jaspers et al. could not initiate an IPD MA on proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, receiving five favourable responses among 18 contacts [38]. The Cochrane Epilepsy Group recently reported their difficulties in performing review updates, with IPD obtained for only 299 participants (four studies) among the 7,811 eligible (37 studies identified) [39].

Possible explanations and implications

The arguments given by corresponding authors for refusing to send IPD agree with the barriers to data sharing described in the literature: concerns about protecting patient confidentiality and anonymity [1, 7, 40], lack of time and costs [1], and unusable datasets [1]. Practical solutions and guidelines to circumvent those obstacles have been proposed [12, 14, 40, 41], but significant efforts must be made to raise the awareness of the surgical community about the benefits of data sharing. Data sharing is a necessary condition to perform IPD meta-analyses, recognized as providing the highest level of evidence. This type of study is of great interest in domains for which randomized controlled trials are difficult to perform, such as in surgery to increase precision and power, to improve external validity and to perform subgroup analyses. Nevertheless, to be relevant, an IPD meta-analysis should be based on all relevant evidence and not on a subset (potentially biased) of eligible trials [1, 2, 8]. In this study, we focused on orthopaedics but it is likely that other surgical domains may be concerned. In a recent methodological review of 583 identified IPD meta-analyses, only 22 (4 %) concerned a surgical intervention [4].

Things are moving with a push toward more data sharing among researchers and some journals [21, 22] that require authors to make the relevant anonymized patient-level data available on reasonable request and to provide a data sharing statement in each article. Major academic funders as well as some pharmaceutical companies are also adopting policies to support this sharing of data. This movement should also spread to surgical domains. Specialized journals, learned societies, funders as well as research leaders have a major role to play to help improve data sharing in surgical domains. Nevertheless, there are practical issues as sharing data 10 years after the completion of a trial may be difficult related to availability and format of data, and because there is no patient consent. The responsibility for cleaning, storing and sharing databases is so far supported by individual researchers. As outlined in an article published in Current Biology, in the long term, research data cannot be reliably preserved by individual researchers [32]. Data cleaning, storage and export in a suitable format represent an important burden for researchers with no specific funding dedicated to this process. Also, investigators may move to another institution, which presents difficulties in contacting them. Therefore, institutions and funders should have the responsibility for data storage. A major change could be obtained by the establishment of central repositories, domain by domain, with close collaboration between researchers, funders and learned societies to securely deposit IPD in a standardized format promptly after trial completion. The development of such repositories is ongoing in some domains, such as rheumatology with the Osteoarthritis Trial Bank [42]. Patient consent to deposit anonymous data on a repository and standardization of data could be planned along with the clinical trial to facilitate the process. Finally, as recently outlined by Ioannidis, the current system does not reward enough data sharing [43]. Additional value should be given to researchers who agree to share their data.

Conclusions

The present study illustrates the difficulties in initiating IPD MAs in orthopaedic surgery. Even under the most favourable conditions (recent trials, request by the French Cochrane Centre, co-authorship, coverage of costs related to data extraction), the number of trials for which IPD could be obtained was low. Significant efforts must be made by the different players in medical research to improve data sharing in the surgical community.

Key messages

This study outlines the practical difficulties in performing IPD MAs in orthopaedics.

We obtained a response rate of 25 % to our request for IPD, with only 14 % of authors agreeing to send IPD.

Overall, we obtained agreement for IPD sharing concerning 5,110 of 33,602 eligible patients.

We obtained agreement to receive IPD for more than half of participants for only one of the 38 IPD MA projects that could have been initiated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Elise Diard (French Cochrane Centre) for help with figures and Isabelle Pane (Centre d'epidemiologie clinique) for sending emails. Philippe Ravaud is director of the French EQUATOR Centre and a member of the EQUATOR Network Steering Group.

Funding

The researchers did not receive external sources of funding.

Abbreviations

- IPD

Individual patient data

- MA

Meta-analysis

- PICO

Population, Intervention tested, Comparator and primary Outcomes

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

Additional files

Search equation of systematic reviews with meta-analysis of aggregated data assessing orthopaedic surgical procedures.

Example of protocol synopsis for individual patient data meta-analysis.

Description of emails sent to the corresponding author to ask for individual patient data.

Flow chart describing the selection process of systematic reviews with meta-analysis of aggregated data assessing orthopaedic surgical procedures.

Main characteristics of the systematic reviews with meta-analysis of aggregated data published in 2013 (n = 63).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

BV designed the study, performed the literature search, extracted data, performed statistical analysis, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. AD designed the study, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. PB performed the literature search, extracted data and interpreted the results. PR generated the idea for study, designed the study, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Benoit Villain, Email: benoit_villain@hotmail.fr.

Agnès Dechartres, Email: agnes.dechartres@htd.aphp.fr.

Patrick Boyer, Email: patrickboyer@free.fr.

Philippe Ravaud, Email: philipperavaud@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Riley RD, Lambert PC, Abo-Zaid G. Meta-analysis of individual participant data: rationale, conduct, and reporting. BMJ. 2010;340:c221. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed I, Sutton AJ, Riley RD. Assessment of publication bias, selection bias, and unavailable data in meta-analyses using individual participant data: a database survey. BMJ. 2012;344:d7762. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Walraven C. Individual patient meta-analysis–rewards and challenges. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:235–237. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hannink G, Gooszen HG, van Laarhoven CJ, Rovers MM. A systematic review of individual patient data meta-analyses on surgical interventions. Syst Rev. 2013;2:52. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross JS, Lehman R, Gross CP. The importance of clinical trial data sharing: toward more open science. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:238–240. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.965798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilhelm EE, Oster E, Shoulson I. Approaches and costs for sharing clinical research data. JAMA. 2014;311:1201–1202. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dechartres A, Ravaud P. Reply to W. Read. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:603–604. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.7217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riley RD, Simmonds MC, Look MP. Evidence synthesis combining individual patient data and aggregate data: a systematic review identified current practice and possible methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:431–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gotzsche PC. Why we need easy access to all data from all clinical trials and how to accomplish it. Trials. 2011;12:249. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eysenbach G, Sa ER. Code of conduct is needed for publishing raw data. BMJ. 2001;323:166. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7305.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagelkerke NJ, Bernsen RM, Rizk DE. Authors should publish their raw data. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18:1387–1390. doi: 10.1007/s00192-007-0464-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hrynaszkiewicz I, Norton ML, Vickers AJ, Altman DG. Preparing raw clinical data for publication: guidance for journal editors, authors, and peer reviewers. BMJ. 2010;340:c181. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vickers AJ. Making raw data more widely available. BMJ. 2011;342:d2323. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hrynaszkiewicz I, Altman DG. Towards agreement on best practice for publishing raw clinical trial data. Trials. 2009;10:17. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Shahi Salman R, Beller E, Kagan J, Hemminki E, Phillips RS, Savulescu J, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in biomedical research regulation and management. Lancet. 2014;383:176–185. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62297-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodwin MA, Abramson JD. Clinical trial data as a public good. JAMA. 2012;308:871–872. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.9661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institutes of Health (NIH). Final NIH statement on sharing research data; 2003. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/notice-files/NOT-OD-03-032.html (accessed 20 Oct 2014).

- 18.Medical Research Council (MRC). MRC policy on research data sharing. http://www.mrc.ac.uk/research/research-policy-ethics/data-sharing/policy/ (accessed 20 Oct 2014).

- 19.Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Information sharing approach. http://www.gatesfoundation.org/How-We-Work/General-Information/Information-Sharing-Approach (accessed 20 Oct 2014).

- 20.The Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Collaboration policies. 2.7 Access to data from all trials. http://www.cochrane.org/organisational-policy-manual/27-access-data-all-trials (accessed 20 Oct 2014).

- 21.PLoS Medicine. PLOS Editorial and Publishing Policies. Materials and software sharing. http://www.plosone.org/static/policies.action#sharing (accessed 20 Oct 2014).

- 22.Godlee F, Groves T. The new BMJ policy on sharing data from drug and device trials. BMJ. 2012;345 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groves T. The wider concept of data sharing: view from the BMJ. Biostatistics. 2010;11:391–392. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxq031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell P. Data’s shameful neglect. Nature. 2009;461:145. doi: 10.1038/461145a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharing public health data: necessary and now. Lancet. 2010;375:1940. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club. 1995;123:A12–A13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011). Oxford: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. http://www.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed 20 Oct 2014).

- 28.R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; 2013. http://www.r-project.org.

- 29.Bhandari M, Richards RR, Sprague S, Schemitsch EH. The quality of reporting of randomized trials in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery from 1988 through 2000. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:388–396. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200203000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campbell AJ, Bagley A, Van Heest A, James MA. Challenges of randomized controlled surgical trials. Orthop Clin North Am. 2010;41:145–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mundi R, Chaudhry H, Mundi S, Godin K, Bhandari M. Design and execution of clinical trials in orthopaedic surgery. Bone Joint Res. 2014;3:161–168. doi: 10.1302/2046-3758.35.2000280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vines TH, Albert AY, Andrew RL, Debarre F, Bock DG, Franklin MT, et al. The availability of research data declines rapidly with article age. Curr Biol. 2014;24:94–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Staples MP, Kallmes DF, Comstock BA, Jarvik JG, Osborne RH, Heagerty PJ, et al. Effectiveness of vertebroplasty using individual patient data from two randomised placebo controlled trials: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;343:d3952. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rathi V, Dzara K, Gross CP, Hrynaszkiewicz I, Joffe S, Krumholz HM, et al. Sharing of clinical trial data among trialists: a cross sectional survey. BMJ. 2012;345 doi: 10.1136/bmj.e7570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rathi VK, Strait KM, Gross CP, Hrynaszkiewicz I, Joffe S, Krumholz HM, et al. Predictors of clinical trial data sharing: exploratory analysis of a cross-sectional survey. Trials. 2014;15:384. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Savage CJ, Vickers AJ. Empirical study of data sharing by authors publishing in PLoS journals. PLoS One. 2009;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wicherts JM, Borsboom D, Kats J, Molenaar D. The poor availability of psychological research data for reanalysis. Am Psychol. 2006;61:726–728. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jaspers GJ, Degraeuwe PL. A failed attempt to conduct an individual patient data meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2014;3:97. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-3-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nolan S, Marson A, Tudur Smith C. Data sharing: is it getting easier to access individual participant data? Experiences from the Cochrane Epilepsy Group. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2014;1–150.

- 40.Vickers AJ. Whose data set is it anyway? Sharing raw data from randomized trials. Trials. 2006;7:15. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mello MM, Francer JK, Wilenzick M, Teden P, Bierer BE, Barnes M. Preparing for responsible sharing of clinical trial data. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1651–1658. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhle1309073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Middelkoop M, Dziedzic KS, Doherty M, Zhang W, Bijlsma JW, McAlindon TE, et al. Individual patient data meta-analysis of trials investigating the effectiveness of intra-articular glucocorticoid injections in patients with knee or hip osteoarthritis: an OA Trial Bank protocol for a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2013;2:54. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-2-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ioannidis JP. How to make more published research true. PLoS Med. 2014;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]