SYNOPSIS

Fish oil is rich in omega-3 fatty acids which have been shown to be beneficial in multiple disease states that involve an inflammatory process. It is now hypothesized that omega-3 fatty acids may decrease the inflammatory response and be beneficial in critical illness. After a review of the mechanisms of omega-3 fatty acids in inflammation, research using enteral nutrition formulas and parenteral nutrition lipid emulsions fortified with fish oil are examined. The results of this research to date are inconclusive for both enteral and parenteral omega-3 fatty acid administration. More research is required before definitive recommendations can be made on fish oil supplementation in critical illness.

Keywords: Omega-3 fatty acids, fish oil, acute lung injury, sepsis, critical illness, mechanical ventilation

INTRODUCTION

The omega-3 fatty acids (FA) found in fish oil are essential and are thought to play a key role as a preventative and therapy for coronary artery disease, diabetes, hypertension, arthritis, cancer, and other inflammatory and autoimmune disorders.(1) In the last decade, omega-3 FA research has focused on their role in decreasing the production of inflammatory cytokines and eicosanoids and thus their potential benefit in critically ill patients. Sepsis is the leading cause of death in critically ill patients in the United States,(2) and sepsis causes the majority of case of acute lung injury (ALI), an inflammatory syndrome of hypoxemic respiratory failure and diffuse pulmonary infiltrates.(3) It is believed that the physical response to sepsis and to other forms of critical illness including ALI and trauma result from massive activation of the inflammatory cascade as well as immunosuppression, or immunoparalysis.(4–6) One feature of uncontrolled activation of the inflammation involves excessive production of proinflammatory cytokines and lipid-derived inflammatory mediators termed eicosanoids,(7) and a relatively new area of research has investigated the role of lipids provided during nutritional support of critically ill patients on both the stress response and clinical outcomes.

This review examines the role of omega-3 fatty acids in the inflammatory process and clinical research in which omega-3 FAs are administered both enterally and parenterally. Although research conducted in all critically ill patient populations is examined, more attention is focused on patients with sepsis or ALI due to their amplified inflammatory response.

OMEGA-3 FATTY ACIDS AND INFLAMMATION

The physiologic response to inflammation is complicated and includes increased blood flow and capillary permeability, thus allowing large molecules including antibodies and cytokines to reach damaged tissues. Although a normal response to infection or injury, inflammation can occur on a massive and uncontrolled scale, thus leading to excessive tissue damage and potential worsening of illness. This “overactivation” of the inflammatory response is characterized by high levels of cytokines including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, and IL-6, which, when present in excess, can be quite destructive and have been implicated in many of the pathologic responses that occur during severe sepsis and ALI.(5, 7)

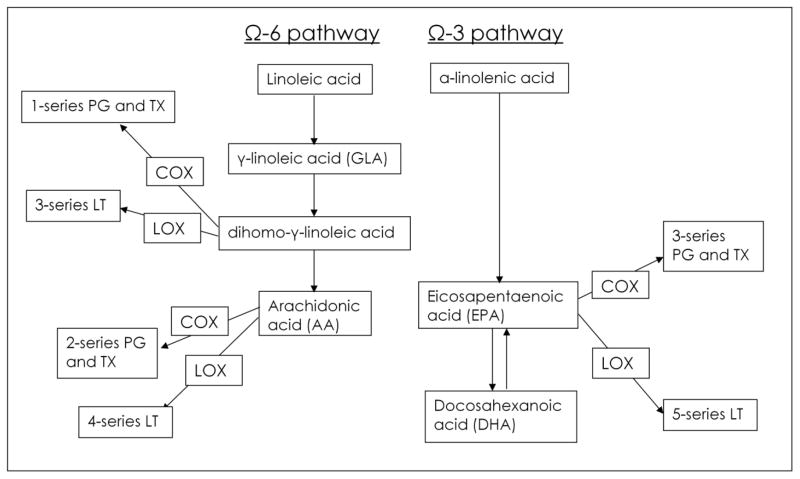

The inflammatory response can be affected by phospholipids in the membranes of immune cells including macrophages, monocytes, and neutrophils. The fatty acid (FA) composition of cell membranes influences the fluidity of the membrane, which in turn can influence the activity of membrane-bound proteins such as enzymes, receptors, transporters, and lipid-based second messenger systems (“lipid signaling”).(8–10) Additionally, particular types of FAs affect the inflammatory response by providing the substrate for production of lipid inflammatory mediators including the eicosanoids. The primary unsaturated long-chain fatty acids in human cellular membranes include the omega-3 FAs eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexanoic acid (DHA), omega-6 FA arachidonic acid (AA), and omega-9 FA oleic acid.(11) Leukocyte membrane phospholipids are usually composed of approximately 30% polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs).(11) Under a typical Western diet, the vast majority of PUFAs are omega-6 FAs (primarily AA), while only a small percentage are omega-3 FAs (12) AA is an omega-6 FA formed from linoleic acid which is present in high concentration in corn, sunflower, soybean and safflower oils. With activation of the inflammatory cascade, macrophages are able to mobilize up to 40% of its membrane lipid content by phospolipases to produce free AA.(11) Free AA is then further metabolized by cycloxygenase (COX) and 5-lipoxygenase (LOX) into pro-inflammatory eicosanoids, including the 2-series thromboxanes and prostaglandins and the 4-series leukotrienes(11) (Fig. 1). The affects of these eicosanoids in inflammation are well understood, especially thromboxane A2 (TXA2), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), and leukotriene B4 (LTB4).(13) TXA2 increases platelet aggregation, leukocyte adhesion, vascular permeability, pulmonary vasoconstriction, and bronchoconstriction,(14–15) and it has pro-thrombotic effects which may lead to tissue ischemia.(11) PGE2 induces vasodilation, fever, vascular permeability during sepsis.(11, 13–14) LTB4 activates leukocytes resulting in the generation of reactive oxygen species, release of proteases such as elastase, synthesis of lipid mediators, and neutrophil chemotaxis.(11) Of interest, platelet-activating factor (PAF) is tightly involved in the regulation of eicosanoid release through a two step activation process including phospholipase A2-dependent cleavage of membrane phospholipids, resulting simultaneously in the release of the active lipid mediator and free AA.(16)

Figure 1.

Eicosanoids Derived from Omega-6 and Omega-3 Fatty Acids. AA, arachidonic acid; COX, cycloxygenase; DHA, docosahexanoic acid; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; LOX, lipoxygenase; LT, leukotriene; PG, prostaglandin; TX, thromboxane.

The omega-3 FAs EPA and DHA are essential for normal growth and development and are highly enriched in the cell membranes of the brain and the eye. They have several known anti-inflammatory mechanisms of action and are effective in the secondary prevention of myocardial infarction and may have a role in the prevention and treatment of diabetes, hypertension, hypertriglyceridemia, and cancer as well as autoimmune disorders. The richest source of EPA and DHA is in fish oil, and increased dietary consumption increases incorporation into inflammatory cell membranes.(17) Omega-3 FAs replace AA in the phospholipid membrane; therefore, AA concentration is reduced and production of the highly inflammatory AA-derived eicosanoids is decreased due to substrate restriction. In addition to this replacement mechanism, EPA also inhibits the metabolism of AA into the inflammatory eicosanoids and is itself metabolized to a far less inflammatory series of eicosanoids (PGE3 and LTB5) than those derived from AA.(18–19) Fish oil has been shown in animal studies to decrease production of AA-derived eicosanoid inflammatory mediators by 40 to 70%.(20–21) In murine models of ALI, endogenous synthesis of omega-3 fatty acids in transgenic mice (22) or intravenous infusion of a fish oil-based lipid emulsion decreased edema formation, leukocyte infiltration, and sickness behavior (23–24). Exogenous delivery of fish oil reduced TNF-α while endogenous synthesis of omega-3 FA did not alter TNF-alpha generation but reduced generation of the pro-inflammatory nuclear factor (NF)-kappa B

An additional mechanism of action involving EPA and DHA has also recently been described. It is now known that resolution of inflammation is an active process, rather than simply absence of inflammatory signals.(25) Novel molecules called resolvins, protectins, and maresins (26–27); lipid mediators derived from EPA and DHA with potent pro-resolving, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective properties,(28–29) have been found to play an important role in the repair and resolution of inflammation.(30) Resolvin (Rv) E1 and Protectin D1 are quite well characterized resolving mediators effective in animal models of colitis and airway inflammation.(31–33) RvE1 has been found to activate cells by binding to an adopted orphan receptor called ChemR23, thereby decreasing the generation of the pro-inflammatory nuclear factor (NF)-kappa B.(34) In addition, it competes with binding of LTB4 to its receptor(35) leading to decreased activation of leukocytes. Administration of resolvin D2 has been shown to improve outcomes in a murine model of abdominal sepsis.(36)

In addition to mechanisms at the level of the cell membrane and involving resolvins and protectins, omega-3 FA may also have direct cardiac effects by interfering with ion-channels in cardiac myocytes. It has been suggested that omega -3 FA or derived metabolites may inhibit the delayed rectifier potassium channel or fast voltage-dependent sodium channels and L-type calcium channels, thereby reducing the arrhythmogenic potential in cardiac myocytes.(37) Of interest, one single center study in cardiac surgical patients suggested a reduced occurrence of post-operative atrial fibrillation after oral administration of n-3 FA.(38) These data are supported by another single center study in 102 cardiac surgical patients receiving either an intravenous fish oil-based lipid emulsion (Omegaven®, Fresenius Kabi, Bad Homburg, Germany) compared to a standard soybean-based lipid emulsion (Lipoven®, Fresenius Kabi, Bad Homburg, Germany). The authors reported reduced occurrence of post-operative atrial fibrillation and shorter length of stay in intensive care and hospital (39).

In addition, omega-3 FAs may affect the autonomic nerve system as well as the neuro-endocrine axis. Prior studies have demonstrated that dietary EPA and DHA reduces resting heart rate and improves heart rate variability.(40–41) EPA and DHA also reduced the generation of adrenocorticotropic hormone and norepinephrine in volunteers challenged with intravenous endotoxin,(42–43) and a fish oil-containing lipid emulsion in post-operative critically ill patients resulted in a trend to lower body temperature in a single center study. (44)

Although supplementation with omega-3 FAs is generally thought to reduce the unfavorable inflammatory effects of omega-6 FAs through the above mechanisms(45), there is also one omega-6 FA, gamma-linolenic acid (GLA), that may provide benefit in critical illness. GLA is found in evening primrose oil, black current seeds and borage oil and is rapidly converted to dihomo-GLA which is incorporated into immune cell phospholipids and which in principle should be further converted to AA.(46) However, GLA actually reduces the availability of AA and synthesis of AA-derived eicosanoids through unclear mechanisms. Dihomo-GLA is further metabolized to prostaglandin E1 (PGE1), a strong pulmonary and systemic vasodilator (Fig. 1).(47) In animal models of critical illness GLA with EPA and DHA have an additive effect to decrease inflammation and organ failure.(48) With this potential additive effect in mind, as discussed below, much of the omega-3 research in critically ill patients with sepsis and ALI has been conducted using a commercially available enteral feeding formula that contains EPA, DHA, GLA, and several antioxidant vitamins.(49–51)

ENTERAL OMEGA-3 FATTY ACIDS IN CRITICAL ILLNESS

Commercially available enteral nutrition formulas with added fish oil have been studied in mixed ICU populations; separately in surgical or medical ICU patients, and in critically ill patients with trauma or burns. Interpretation of data in this area is difficult due to differing amounts of EPA and DHA present in various enteral formulations (1.0–6.6 g/L) and the inclusion of other micronutrients in the formulas. (52) Furthermore, the degree of clinical response to fish oil containing formulas may vary between patients due to the type and severity of illnesses in the populations studied.

Due to the severe inflammatory response in patients with ALI and sepsis, many anti-inflammatory agents, including omega-3 FAs, have been investigated as potential therapies in these populations. Three randomized clinical trials (RCTs) using a commercial feeding formula (Oxepa®; Abbott Nutrition, Abbott Laboratories, Columbus, Ohio) which contains EPA, DHA, GLA, and several antioxidants in critically ill patients have been completed and published. Two of these RCTs included only patients with ALI (49–50) and the third studied patients with sepsis (51) (although nearly all of the patients in the third RCT had single-organ lung failure, i.e. ALI). All three of these trials randomized patients to receive either the enteral formula containing EPA, DHA, GLA, and antioxidants (Oxepa®) or an isonitrogenous, high-fat, low-carbohydrate enteral feeding formula that did not contain fish oil. One of the studies used a different control formula which was equal in fat content (55% fat) but differed in lipid composition from the control formulation used by the other two studies.(51) In Gadek et al. and Singer et al., the lipid content of the control formula was 97% corn oil, which is high in linoleic acid, an omega-6 FA.(49–50) The lipid in the control formula in Pontes-Arrudes et al. was 55.8% canola oil, 14% corn oil, 20%MCT, 7% high oleic safflower oil and 3.2% soy lecithin.(51)

In the first study, subjects in the treatment group received approximately of 7g EPA, 3g DHA, and 6g GLA per day.(49) Serial bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was done at study entry, day 4, and day 7. The treatment group had improved oxygenation at days 4 and 7 (p<0.0499); decreased duration of mechanical ventilation (p=0.027), reduced BAL fluid neutrophil (representing decreased lung inflammation) count at day 4 (p=0.008), decreased ICU length of stay (p=0.016), and new organ failures (p=0.018). Mortality was 16% in the treatment group and 25% in the control group (p=0.165).

In the second trial by Singer and co-workers, patients in the EPA/DHA/GLA/antioxidant group had a shorter, but statistically insignificant, duration of mechanical ventilation at day 14.(50) Hospital mortality in this study was very high (>75%) in both groups 3 months after the intervention.

The third trial in patients with sepsis (most of whom had ALI) found significant increases in ICU-free days (p<0.001), in ventilator-free days (p<0.001), and 28-day survival (52% vs. 33%, p=0.04) in the treatment group.(51) All patients tolerated near goal enteral feeding. Development of new organ dysfunctions was also reduced (p<0.001) in patients receiving the formula enriched with EPA, DHA and GLA.

In a meta-analysis of these three studies, the data from a total of 411 patients (296 who were considered evaluable) was analyzed.(47) The use of the treatment formula enriched with EPA, DHA, GLA and antioxidants was associated with a 60% reduction in the risk of 28-day all cause mortality (OR=0.40; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.24–0.68; p=0.001). Significant reductions were also found in the risk of developing new organ failures (OR = 0.17; 95% CI=0.08–0.34; p<0.0001), time on mechanical ventilation (standardized mean difference [SMD]=0.56; 95% CI=0.32–0.79; p<0.0001), and in length of stay in the ICU (SMD=0.51; 95% CI=0.27–0.74; p<0.0001) in patients who received the formula containing fish oil. A second meta-analysis by Marik & Zaloga confirmed the findings reporting improved mortality (OR 0.42, CI 0.26–0.68, p <0.001), secondary infections (OR 0.45, 95% CI 0.25–0.79, p<0.005), and length of stay (WMD −6.28 days, 95% CI −9.92 to −2.64) in patients who received enteral formulas that contained fish oil. (52) These studies have also been reviewed as part of the Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines for enteral nutrition supplemented with fish oils, available at www.criticalcarenutrition.com; and are evaluated in the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N) 2009 Critical Care Guidelines.(53–54)

Two additional publications from the randomized clinical trial by Gadek et al.(49) investigated mechanisms of action of EPA, DHA, GLA and antioxidants in patients with ALI. The first investigation reported on the antioxidant status of the participants with ALI and compared them to a group of healthy controls.(55) At enrollment, the patients with ALI had reduced levels of antioxidant vitamins and were found to be in a state of oxidative stress (as measured by total radical antioxidant potential and lipid peroxide levels) compared to healthy controls. After receiving the treatment formula, the levels of oxidative stress were not significantly reduced, but plasma levels of β-carotene and α-tocopherol were restored to normal while lipid peroxide levels did not increase; thus suggesting the antioxidants may have protected against further lipid peroxidation. The second ancillary study reported a significantly reduced level of interleukin-8 (a potent inflammatory cytokine and neutrophil chemoattractant) in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of patients in the treatment group (p=0.05), as well as a trend toward reduced levels of IL-6, LTB4 and TNF-α.(56) Because the above trials investigated a single enteral formula (Oxepa®) containing multiple pharmaconutrients, the benefit attributed exclusively to omega-3 FAs is unknown.

Other enteral nutritional formulas enriched with omega-3 FAs have been studied in critically ill patients suffering from trauma, surgery, or burns. These formulas are usually supplemented with additional nutrients thought to affect immune function, such as the amino acids arginine or glutamine or antioxidant vitamins (57) The above mentioned meta-analysis by Marik & Zaloga analyzed data from enteral nutrition studies and separated the studies by the types of micronutrients included in the formula (fish oil, arginine or glutamine) and the population studied (surgical ICU, medical ICU, mixed ICU, burns, or trauma).(52) All studies in non-medical ICU patients included in this meta-analysis used a formula that also contained arginine. Mixed ICU patients with sepsis and ALI improved with the addition of fish oil to enteral feedings, but supplementation with fish oil and arginine (with or without glutamine) did not show benefit for patients in the surgical ICU or for those with trauma or burns.(52) Another meta-analysis has suggested that formulas containing arginine may benefit elective surgical patients but may be harmful to critically ill patients with sepsis.(58) Use of arginine containing formulas in critically ill patients showed a trend toward higher mortality, while there was no such effect in elective surgical patients.(58) Therefore, a negative effect or lack of benefit with use of these formulas that contain both arginine and fish oil in critically ill patients may be related to the arginine and not the omega-3 FAs, especially in critically ill medical ICU patients with sepsis.

When pharmaconutrients are combined with macronutrients in enteral feedings, it is difficult to generalize study results. Two recently completed, but not yet published, RCTs of omega-3 FAs in patients with ALI were designed to dissociate the pharmaconutrients from enteral feedings; the pharmaconutrients were administered enterally as medications while patients received standard enteral nutrition regimens per their treating physicians.(59–60) The preliminary results of these two recent RCTs were presented orally at the American Thoracic Society (ATS) International Conference held May 15–20, 2009 in San Diego, California. Both of these trials appear to challenge the positive results found in the previous RCTs using the enteral formula containing EPA, DHA, GLA, and antioxidants.(59–60) The first trial, the OMEGA study, is a large phase III RCT conducted by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network (ARDSnet) to investigate whether an enteral supplement (delivered twice daily) containing EPA, DHA, GLA, and antioxidants would have benefit in patients with ALI.(60) This RCT was stopped due to lack of efficacy in March 2009 after accrual of 272 of the planned 1000 patients. The enteral supplement did not improve the outcomes of ventilator free days at day 28, ICU free days at day 28, or death at 60 days. The second study reported at the conference was a phase II randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of enteral fish oil (EPA and DHA) in 90 critically ill patients with ALI.(59) Fish oil or a saline placebo was given enterally as a medication, separate from enteral or parenteral nutrition in this trial. The primary endpoint was BAL fluid IL-8 and secondary endpoints included clinical outcomes as well as biomarkers of inflammation and injury, oxygenation, and lung compliance. None of the primary or secondary endpoints were significantly different between the treatment and control groups. Based on the preliminary results available from these two studies, the effect of enteral fish oil supplementation in patients with ALI and sepsis is currently unclear. Some limitations of the three earlier studies using the enteral formula enriched with EPA, DHA, GLA and antioxidants in patients with ALI include the small number of published studies to date, and the use of a control formula in two of the studies(49–50) that was high in linoleic acid, an omega-6 FA. It is currently unclear why the promising effect of the previous studies could not be reproduced in the two newer (unpublished) studies. There are differences between the designs of the different studies including the intervention, control formulas, and continuous administration vs. bolus administration of the agent.

Most studies investigating the effects of enteral fish oils included in an enteral feeding formula with other nutrients including arginine, glutamine, or antioxidants have been in non-medical ICU patents with trauma,(61–62) burns,(63–64) or surgery(65–66) and have found no benefits in mortality, length of hospital stay, or rates of new infections. However, many of these studies were small, with some intending only to detect differences in biochemical parameters or biomarkers. One large multi-center study in septic patients examined the effect of fish oil, arginine, and nucleotides and did demonstrate an improvement in mortality.(67) However, in subgroup analysis the overall effect was largely due to patients with a low Acute Physiologic and Health Evaluation Score (APACHE II), and mortality was actually worse in patients with a APACHE II score > 25. Therefore the effect of enteral fish oil in these populations is not clear. However, this conclusion is based on a small number of studies in each population.(52) Additional research is needed before any definitive recommendations can be made about enteral omega-3 FA supplementation in critically ill patients.

INCLUSION OF OMEGA-3 FATTY ACIDS IN PARENTERAL NUTRITION

Lipid emulsions are generally administered in parenteral nutrition (PN) regimens to provide a source of energy and essential fatty acids, and the specific type of fatty acids in the emulsions may impact the inflammatory response in critical illness. Soybean oil, consisting of roughly 54% linoleic acid (an omega-6 FA), is the lipid traditionally used in PN.(68) Concern has been raised over the potential pro-inflammatory, pro-coagulatory, and immunosuppressive properties of linoleic acid. However, clinical trials using these emulsions have provided conflicting evidence.(69) A meta-analysis of two studies(70–71) where standard lipids in PN were compared with no lipids suggested that PN with standard lipids may result in a higher infectious complication rate (p=0.02) than PN without lipids, although mortality was not different between the two groups.(72) The concern about lipid emulsions has led to new formulations which partially replace soybean oil with other oils including medium chain triglycerides (MCT), olive oil, or fish oil.(69)

Recent studies using parenteral fish oil emulsions have been conducted. In a study by Mayer et al.,(73) 21 who required PN due to intolerance of enteral nutrition were randomized in an open-label trial to receive an omega-3 FA lipid emulsion (Omegaven®; Fresenius Kabi, Bad Homburg, Germany) or a standard omega-6 lipid emulsion (Lipoven®; Fresenius Kabi) for 5 days. The omega-3 rich emulsion increased plasma concentrations of omega-3 free FAs and reversed the omega-3/omega-6 ratio toward favoring EPA and DHA over AA, reaching maximum effect in 3 days. In patients receiving the fish oil emulsion, EPA and DHA rapidly incorporated into mononuclear leukocyte cell membranes, increasing threefold in concentration. Ex vivo, these cells produced 30% less TNF-α, interleukin 1-β, IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 when stimulated by endotoxin. However, serum cytokine levels between the patients receiving parenteral omega-3 FAs and the standard lipid emulsion were not different. In another study by the same authors, 10 patients with septic shock requiring PN randomly received fish oil fortified Omegaven® or the standard omega-6 rich Lipoven® for a total of 10 days.(74) C-reactive protein levels and leukocyte counts decreased in patients receiving the omega-3 emulsion and increased in patients receiving the omega-6 emulsion, with a trend toward significance (p=0.08 and p=0.09, respectively). Patients in the omega-6 group trended towards longer ventilation time (p=0.07). LTB5 increased in the fish oil group, approaching an LTB4/LTB5 ratio of almost 20% by the end of the study infusion period. These results support the hypothesis that parenteral omega-3 FA in patients with septic shock modulates inflammatory mediator production and attenuates inflammation.

In a prospective, open label trial, infusion of omega-3 FAs during PN (Omegaven® ) improved diagnosis-related clinical outcomes in critically ill patients with major abdominal surgery (n=255), peritonitis and abdominal sepsis (n=276), non-abdominal sepsis (n=16), multi-trauma (n=59), severe head injury (n=18) or other diagnoses (n=37).(75) Both ICU and hospital lengths of stay were significantly reduced (both p<0.001) with doses of >0.05 gm fish oil/kg/day, and patients receiving >0.15 gm/kg/day needed less antibiotic treatment. Mortality was significantly decreased (p<0.05) in patients receiving >0.1 gm fish oil/kg/day. In an analysis of patients by diagnosis, according to mean fish oil dose received, patients with severe head injury (p<0.0001), multiple trauma (p<0.0001), and abdominal sepsis (p=0.0027), had significantly lower mortality. These results suggest benefit from parenteral omega-3, but this study was not controlled or blinded. Another recent trial randomized patients with severe acute pancreatitis to either a combination of 20% Omegaven® + 80% Lipoven® or Lipoven® alone.(76) There were no significant differences in white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, rates of organ dysfunction, infectious complications, or ICU length of stay. However, IL-6 decreased to a significantly greater degree between baseline and day 6 in patients in the fish oil group (p < 0.05). Additionally, oxygenation was significantly increased (p<0.05) and there was a significantly decreased need for renal replacement therapy (p<0.05) in the patients receiving fish oil.

In contrast to the positive results of the previous studies which were largely in surgically critically ill patients, a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial in critically ill medical patients found no clear medical benefit to parenteral omega-3 FAs.(77) In that study, 166 medical ICU patients were randomized to receive a mixture of medium- and long-chain triglycerides (Lipofundin MCT®; Braun Medical, Melsungen, Germany) or a combination of Omegaven® and Lipofundin MCT® for 7 days. Based on data from a prior study,(78) this RCT was designed to detect a biologic endpoint: more rapid reduction in IL-6 and greater monocyte expression of HLA-DR, a marker of immune competence, in the omega-3 group. The authors found no differences in IL-6 or HLA-DR between the treatment groups, nor did they detect differences in mortality, duration of mechanical ventilation, ICU length of stay, infectious complications, other inflammatory markers, or bleeding events.(77) One possible explanation for this lack of effect is that the start of the study occurred after the initial inflammatory process was already resolving. In addition, the study may have been underpowered. This study also used a control lipid emulsion that was lower in omega-6 FAs (due to the presence of MCT) than most standard lipid emulsions, and thus may have been less inflammatory.(77) Recently, another single center study in patients with the systemic inflammatory response syndrome was published where a parenteral lipid emulsion of MCT, soybean oil, and fish oil was compared to a lipid emulsion of MCT and soybean oil alone (Lipofundin-MCT®).(79) They reported a faster reduction in IL-6, improved ventilation parameters, and a trend toward reduced hospital length of stay (p<0.079).

No adverse effects have been reported with the administration of lipid emulsions fortified with fish oil, suggesting it is safe in critically ill patients.(69) Because available research to date provides conflicting data on the effects of parenteral omega-3 FAs in critically ill patients, its influence on inflammatory processes and clinical outcomes is remains unclear.

CONCLUSIONS

Although much is known about the mechanism of action of omega-3 FAs and their effect on cytokines and inflammatory mediators from research with animals humans, their effects on clinical outcomes in critically ill patients are not entirely clear, and further research is needed to determine any benefit. Trials of nutritional support and micronutrients, including omega-3 FAs, in critically ill patients are especially difficult to conduct and interpret for multiple reasons. First, patient enrollment can be difficult due to issues with surrogate consent as well as the short enrollment periods in most studies (e.g. most trial require enrollment within 24–48 hours after ICU admission in an effort to initiate the agents early in the course of critical illness). Second, critically ill patients are a very heterogeneous population and present with a wide variety of severe medical illnesses. This heterogeneity means that large numbers of patients are required to demonstrate an effect.(80) Third, the delivery of nutrition and micronutrients is frequently interrupted or poorly tolerated in ICU patients, thus resulting in decreased delivery of the agent being studied, especially if it is enteral. Fourth, in many studies of enteral and parenteral nutrients, many agents are frequently combined into one formula, and therefore the effect produced by a single agent cannot be determined. Fifth, choice of control group agent in many trials is also in issue. Finally, dosing data on both enteral and parenteral omega-3 fatty acids in critically ill are very sparse.

Prior research demonstrating positive effects of enteral omega-3 FAs in patients with sepsis and ALI involved the continuous administration of one enteral formula fortified with EPA, DHA, GLA and antioxidants.(49–51) These data are challenged by the use of bolus omega-3 FAs, either as a single enteral agent(59) or as part of an enteral immune-modulating cocktail.(60) The studies of parenteral omega-3 FAs that suggest a benefit have been conducted using a particular lipid emulsion (Omegaven®) and are not yet conclusive.(73–77) After understanding the limitations of all the previous studies and gaining insight into possible dosing-, timing-, and application-dependent effects, it is clear that additional randomized, double-blinded, controlled trials in which omega-3 FAs are administered separately from feedings (and the feeding formulas are devoid of other micronutrients) and the control agent is an inert placebo are needed to definitively inform patient care.

Table 1.

Published Randomized Controlled Trials Comparing a Commercial Enteral Feeding Formula Enriched with EPA, DHA, GLA, and Antioxidants to Another High-Fat Enteral Feeding Formula Without Fish Oils

| Gadek et al.49 | Singer et al.50 | Pontes-Arruda et al.51 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population Studied | ARDS | ALI | Severe Sepsis |

| n=146 | n=100 | n=165 | |

| Study Design | R, C, DB | R, C | R, C, DB |

| Mean Fatty Acid Intake (g/day) | |||

| EPA | 6.9 | 5.4 | 4.9 |

| DHA | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.2 |

| GLA | 5.8 | 5.1 | 4.6 |

| Significant Findingsa | |||

| Improved oxygenation | Yes | Yesb | Yes |

| Reduced ICU length of stay | Yes | No | Yes |

| Reduced ventilator time | Yes | Yesc | Yes |

| Reduced 28-day mortality | No | Yes | Yes |

| Fewer new organ failures | Yes | Not assessed | Yes |

R, randomized; C, controlled; DB, double blind; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; GLA, gamma-linolenic acid; ALI, acute lung injury; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; FA, fatty acid.

Statistically significant (p<0.05);

Days 4, 7 only;

Day 7 only

Contributor Information

Renee D. Stapleton, Email: renee.stapleton@uvm.edu, Department of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care, University of Vermont College of Medicine, 149 Beaumont Avenue, HSRF 222, Burlington, VT, U.S.A. 05405, Tele: (802) 656-7975, Fax: (802) 656-8926.

Julie M. Martin, Email: julie.martin@uvm.edu, Department of Medicine, Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care, University of Vermont College of Medicine, 149 Beaumont Avenue, HSRF 230, Burlington, VT, U.S.A. 05405, Tele: (802) 656-7953, Fax: (802) 656-8926.

Konstantin Mayer, Email: konstantin.mayer@uglc.de, University of Giessen Lung Center (UGLC), Medical Clinic II, Justus-Liebig-University Giessen, Klinikstr. 36, D-35392 Giessen, Germany., Tele: +49-641-99-42112/42351, Fax: +49-641-99-42359.

References

- 1.Simopoulos AP. Essential fatty acids in health and chronic disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999 Sep;70(3 Suppl):560S–569S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.3.560s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med. 2001 Jul;29(7):1303–1310. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200107000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wheeler AP, Bernard GR. Acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome: a clinical review. Lancet. 2007 May 5;369(9572):1553–1564. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60604-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen J. The immunopathogenesis of sepsis. Nature. 2002 Dec 19–26;420(6917):885–891. doi: 10.1038/nature01326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hotchkiss RS, Karl IE. The pathophysiology and treatment of sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2003 Jan 9;348(2):138–150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volk HD, Reinke P, Docke WD. Clinical aspects: from systemic inflammation to ‘immunoparalysis’. Chem Immunol. 2000;74:162–177. doi: 10.1159/000058753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calder PC. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and inflammation: from molecular biology to the clinic. Lipids. 2003 Apr;38(4):343–352. doi: 10.1007/s11745-003-1068-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stubbs CD, Smith AD. The modification of mammalian membrane polyunsaturated fatty acid composition in relation to membrane fluidity and function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984 Jan 27;779(1):89–137. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(84)90005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy MG. Dietary fatty acids and membrane protein function. J Nutr Biochem. 1990 Feb;1(2):68–79. doi: 10.1016/0955-2863(90)90052-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calder PC. The relationship between the fatty acid composition of immune cells and their function. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2008 Sep-Nov;79(3–5):101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bulger EM, Maier RV. Lipid mediators in the pathophysiology of critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2000 Apr;28(4 Suppl):N27–36. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200004001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palombo JD, Lydon EE, Chen PL, Bistrian BR, Forse RA. Fatty acid composition of lung, macrophage and surfactant phospholipids after short-term enteral feeding with n-3 lipids. Lipids. 1994 Sep;29(9):643–649. doi: 10.1007/BF02536099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tilley SL, Coffman TM, Koller BH. Mixed messages: modulation of inflammation and immune responses by prostaglandins and thromboxanes. J Clin Invest. 2001 Jul;108(1):15–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI13416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris SG, Padilla J, Koumas L, Ray D, Phipps RP. Prostaglandins as modulators of immunity. Trends Immunol. 2002 Mar;23(3):144–150. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(01)02154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrak RA, Balk RA, Bone RC. Prostaglandins, cyclo-oxygenase inhibitors, and thromboxane synthetase inhibitors in the pathogenesis of multiple systems organ failure. Crit Care Clin. 1989 Apr;5(2):303–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA, McIntyre TM. Platelet-activating factor. J Biol Chem. 1990 Oct 15;265(29):17381–17384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marangoni F, Angeli MT, Colli S, et al. Changes of n-3 and n-6 fatty acids in plasma and circulating cells of normal subjects, after prolonged administration of 20:5 (EPA) and 22:6 (DHA) ethyl esters and prolonged washout. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993 Dec 2;1210(1):55–62. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(93)90049-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee TH, Menica-Huerta JM, Shih C, Corey EJ, Lewis RA, Austen KF. Characterization and biologic properties of 5,12-dihydroxy derivatives of eicosapentaenoic acid, including leukotriene B5 and the double lipoxygenase product. J Biol Chem. 1984 Feb 25;259(4):2383–2389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golman DWPW, Goetzl EJ. Human neutrophil chemotactic and degranulating activites of leukotriene B5 (LTB5) derived from eicosapentaenoic acid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983;117:282–288. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)91572-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee TH, Hoover RL, Williams JD, et al. Effect of dietary enrichment with eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids on in vitro neutrophil and monocyte leukotriene generation and neutrophil function. N Engl J Med. 1985 May 9;312(19):1217–1224. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198505093121903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whelan J, Broughton KS, Kinsella JE. The comparative effects of dietary alpha-linolenic acid and fish oil on 4- and 5-series leukotriene formation in vivo. Lipids. 1991 Feb;26(2):119–126. doi: 10.1007/BF02544005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang JX, Wang J, Wu L, Kang ZB. Transgenic mice: fat-1 mice convert n-6 to n-3 fatty acids. Nature. 2004 Feb 5;427(6974):504. doi: 10.1038/427504a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaefer MB, Ott J, Mohr A, et al. Immunomodulation by n-3- versus n-6-rich lipid emulsions in murine acute lung injury--role of platelet-activating factor receptor. Crit Care Med. 2007 Feb;35(2):544–554. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000253811.74112.B6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayer K, Kiessling A, Ott J, et al. Acute lung injury is reduced in fat-1 mice endogenously synthesizing n-3 fatty acids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009 Mar 15;179(6):474–483. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200807-1064OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ariel A, Serhan CN. Resolvins and protectins in the termination program of acute inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2007 Apr;28(4):176–183. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Serhan CN, Yang R, Martinod K, et al. Maresins: novel macrophage mediators with potent antiinflammatory and proresolving actions. J Exp Med. 2009 Jan 16;206(1):15–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Serhan CN. Systems approach to inflammation resolution: identification of novel anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving mediators. J Thromb Haemost. 2009 Jul;7 (Suppl 1):44–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Serhan CN, Clish CB, Brannon J, Colgan SP, Chiang N, Gronert K. Novel functional sets of lipid-derived mediators with antiinflammatory actions generated from omega-3 fatty acids via cyclooxygenase 2-nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and transcellular processing. J Exp Med. 2000 Oct 16;192(8):1197–1204. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.8.1197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Serhan CN, Hong S, Gronert K, et al. Resolvins: a family of bioactive products of omega-3 fatty acid transformation circuits initiated by aspirin treatment that counter proinflammation signals. J Exp Med. 2002 Oct 21;196(8):1025–1037. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE. Resolving inflammation: dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008 May;8(5):349–361. doi: 10.1038/nri2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levy BD, Kohli P, Gotlinger K, et al. Protectin D1 is generated in asthma and dampens airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness. J Immunol. 2007 Jan 1;178(1):496–502. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haworth O, Cernadas M, Yang R, Serhan CN, Levy BD. Resolvin E1 regulates interleukin 23, interferon-gamma and lipoxin A4 to promote the resolution of allergic airway inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2008 Aug;9(8):873–879. doi: 10.1038/ni.1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arita M, Yoshida M, Hong S, et al. Resolvin E1, an endogenous lipid mediator derived from omega-3 eicosapentaenoic acid, protects against 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-induced colitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 May 24;102(21):7671–7676. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409271102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arita M, Bianchini F, Aliberti J, et al. Stereochemical assignment, antiinflammatory properties, and receptor for the omega-3 lipid mediator resolvin E1. J Exp Med. 2005 Mar 7;201(5):713–722. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arita M, Ohira T, Sun YP, Elangovan S, Chiang N, Serhan CN. Resolvin E1 selectively interacts with leukotriene B4 receptor BLT1 and ChemR23 to regulate inflammation. J Immunol. 2007 Mar 15;178(6):3912–3917. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.6.3912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spite M, Norling LV, Summers L, et al. Resolvin D2 is a potent regulator of leukocytes and controls microbial sepsis. Nature. 2009 Oct 29;461(7268):1287–1291. doi: 10.1038/nature08541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anand RG, Alkadri M, Lavie CJ, Milani RV. The role of fish oil in arrhythmia prevention. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev. 2008 Mar-Apr;28(2):92–98. doi: 10.1097/01.HCR.0000314202.09676.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Calo L, Bianconi L, Colivicchi F, et al. N-3 Fatty acids for the prevention of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005 May 17;45(10):1723–1728. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Heidt MC, Vician M, Stracke SK, et al. Beneficial effects of intravenously administered N-3 fatty acids for the prevention of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery: a prospective randomized study. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009 Aug;57(5):276–280. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1185301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Keefe JH, Jr, Abuissa H, Sastre A, Steinhaus DM, Harris WS. Effects of omega-3 fatty acids on resting heart rate, heart rate recovery after exercise, and heart rate variability in men with healed myocardial infarctions and depressed ejection fractions. Am J Cardiol. 2006 Apr 15;97(8):1127–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Geelen A, Brouwer IA, Schouten EG, Maan AC, Katan MB, Zock PL. Effects of n-3 fatty acids from fish on premature ventricular complexes and heart rate in humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Feb;81(2):416–420. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.81.2.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pluess TT, Hayoz D, Berger MM, et al. Intravenous fish oil blunts the physiological response to endotoxin in healthy subjects. Intensive Care Med. 2007 May;33(5):789–797. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0591-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michaeli B, Berger MM, Revelly JP, Tappy L, Chiolero R. Effects of fish oil on the neuro-endocrine responses to an endotoxin challenge in healthy volunteers. Clin Nutr. 2007 Feb;26(1):70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berger MM, Tappy L, Revelly JP, et al. Fish oil after abdominal aorta aneurysm surgery. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008 Sep;62(9):1116–1122. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mayer K, Seeger W. Fish oil in critical illness. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2008 Mar;11(2):121–127. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e3282f4cdc6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Singer P, Shapiro H. Enteral omega-3 in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009 Mar;12(2):123–128. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328322e70f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pontes-Arruda A, Demichele S, Seth A, Singer P. The use of an inflammation-modulating diet in patients with acute lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome: a meta-analysis of outcome data. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2008 Nov-Dec;32(6):596–605. doi: 10.1177/0148607108324203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mancuso P, Whelan J, DeMichele SJ, Snider CC, Guszcza JA, Karlstad MD. Dietary fish oil and fish and borage oil suppress intrapulmonary proinflammatory eicosanoid biosynthesis and attenuate pulmonary neutrophil accumulation in endotoxic rats. Crit Care Med. 1997 Jul;25(7):1198–1206. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199707000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gadek JE, DeMichele SJ, Karlstad MD, et al. Effect of enteral feeding with eicosapentaenoic acid, gamma-linolenic acid, and antioxidants in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Enteral Nutrition in ARDS Study Group. Crit Care Med. 1999 Aug;27(8):1409–1420. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199908000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singer P, Theilla M, Fisher H, Gibstein L, Grozovski E, Cohen J. Benefit of an enteral diet enriched with eicosapentaenoic acid and gamma-linolenic acid in ventilated patients with acute lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2006 Apr;34(4):1033–1038. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000206111.23629.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pontes-Arruda A, Aragao AM, Albuquerque JD. Effects of enteral feeding with eicosapentaenoic acid, gamma-linolenic acid, and antioxidants in mechanically ventilated patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006 Sep;34(9):2325–2333. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000234033.65657.B6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marik PE, Zaloga GP. Immunonutrition in critically ill patients: a systematic review and analysis of the literature. Intensive Care Med. 2008 Nov;34(11):1980–1990. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heyland DK. Nutrition Clinical Practice Guidelines 4.1(b) Composition of enteral nutrition: fish oils. 2009 Jan 31; http://www.criticalcarenutrition.com/docs/cpg/4.1bfish%20oils_FINAL.pdf.

- 54.McClave SA, Martindale RG, Vanek VW, et al. Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.) JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2009 May-Jun;33(3):277–316. doi: 10.1177/0148607109335234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nelson JL, DeMichele SJ, Pacht ER, Wennberg AK. Effect of enteral feeding with eicosapentaenoic acid, gamma-linolenic acid, and antioxidants on antioxidant status in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2003 Mar-Apr;27(2):98–104. doi: 10.1177/014860710302700298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pacht ER, DeMichele SJ, Nelson JL, Hart J, Wennberg AK, Gadek JE. Enteral nutrition with eicosapentaenoic acid, gamma-linolenic acid, and antioxidants reduces alveolar inflammatory mediators and protein influx in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2003 Feb;31(2):491–500. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000049952.96496.3E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Calder PC. Immunonutrition in surgical and critically ill patients. Br J Nutr. 2007 Oct;98 (Suppl 1):S133–139. doi: 10.1017/S0007114507832909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heyland DK, Novak F, Drover JW, Jain M, Su X, Suchner U. Should immunonutrition become routine in critically ill patients? A systematic review of the evidence. JAMA. 2001 Aug 22–29;286(8):944–953. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.8.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stapleton RD, Martin TR, Gundel SJ, Crowley JJ, Nathens AB, Watkins TR, Akhtar SR, Martin JM, Ruzinski BS, Caldwell E, Neff MJ. A phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fish oil (eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexanoic acid) on lung and systemic inflammation in patients with acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:A2169. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rice T. Trial of omega-3 fatty acid, gamma-linolenic acid and antioxidant supplemention in the management of acute lung injury (Omega). Paper presented at: American Thoracic Society International Conference; May, 17, 2009; San Diego, California. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Engel JM, Menges T, Neuhauser C, Schaefer B, Hempelmann G. Effects of various feeding regimens in multiple trauma patients on septic complications and immune parameters. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther. 1997 Apr;32(4):234–239. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-995043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weimann A, Bastian L, Bischoff WE, et al. Influence of arginine, omega-3 fatty acids and nucleotide-supplemented enteral support on systemic inflammatory response syndrome and multiple organ failure in patients after severe trauma. Nutrition. 1998 Feb;14(2):165–172. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(97)00429-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saffle JR, Wiebke G, Jennings K, Morris SE, Barton RG. Randomized trial of immune-enhancing enteral nutrition in burn patients. J Trauma. 1997 May;42(5):793–800. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199705000-00008. discussion 800–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wibbenmeyer LA, Mitchell MA, Newel IM, et al. Effect of a fish oil and arginine-fortified diet in thermally injured patients. J Burn Care Res. 2006 Sep-Oct;27(5):694–702. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000238084.13541.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cerra FB, Lehman S, Konstantinides N, Konstantinides F, Shronts EP, Holman R. Effect of enteral nutrient on in vitro tests of immune function in ICU patients: a preliminary report. Nutrition. 1990 Jan-Feb;6(1):84–87. discussion 96–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bower RH, Cerra FB, Bershadsky B, et al. Early enteral administration of a formula (Impact) supplemented with arginine, nucleotides, and fish oil in intensive care unit patients: results of a multicenter, prospective, randomized, clinical trial. Crit Care Med. 1995 Mar;23(3):436–449. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199503000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Galban C, Montejo JC, Mesejo A, et al. An immune-enhancing enteral diet reduces mortality rate and episodes of bacteremia in septic intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med. 2000 Mar;28(3):643–648. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200003000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Suchner U, Katz DP, Furst P, et al. Impact of sepsis, lung injury, and the role of lipid infusion on circulating prostacyclin and thromboxane A(2) Intensive Care Med. 2002 Feb;28(2):122–129. doi: 10.1007/s00134-001-1192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Calder PC. Rationale for using new lipid emulsions in parenteral nutrition and a review of the trials performed in adults. Proc Nutr Soc. 2009 May 11;:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S0029665109001268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McCowen KC, Friel C, Sternberg J, et al. Hypocaloric total parenteral nutrition: effectiveness in prevention of hyperglycemia and infectious complications--a randomized clinical trial. Crit Care Med. 2000 Nov;28(11):3606–3611. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200011000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Battistella FD, Widergren JT, Anderson JT, Siepler JK, Weber JC, MacColl K. A prospective, randomized trial of intravenous fat emulsion administration in trauma victims requiring total parenteral nutrition. J Trauma. 1997 Jul;43(1):52–58. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199707000-00013. discussion 58–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heyland DK, Dhaliwal R, Drover JW, Gramlich L, Dodek P. Canadian clinical practice guidelines for nutrition support in mechanically ventilated, critically ill adult patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2003 Sep-Oct;27(5):355–373. doi: 10.1177/0148607103027005355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mayer K, Gokorsch S, Fegbeutel C, et al. Parenteral nutrition with fish oil modulates cytokine response in patients with sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003 May 15;167(10):1321–1328. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200207-674OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mayer K, Fegbeutel C, Hattar K, et al. Omega-3 vs. omega-6 lipid emulsions exert differential influence on neutrophils in septic shock patients: impact on plasma fatty acids and lipid mediator generation. Intensive Care Med. 2003 Sep;29(9):1472–1481. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1900-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Heller AR, Rossler S, Litz RJ, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids improve the diagnosis-related clinical outcome. Crit Care Med. 2006 Apr;34(4):972–979. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000206309.83570.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang X, Li W, Li N, Li J. Omega-3 fatty acids-supplemented parenteral nutrition decreases hyperinflammatory response and attenuates systemic disease sequelae in severe acute pancreatitis: a randomized and controlled study. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2008 May-Jun;32(3):236–241. doi: 10.1177/0148607108316189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Friesecke S, Lotze C, Kohler J, Heinrich A, Felix SB, Abel P. Fish oil supplementation in the parenteral nutrition of critically ill medical patients: a randomised controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2008 Aug;34(8):1411–1420. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Weiss G, Meyer F, Matthies B, Pross M, Koenig W, Lippert H. Immunomodulation by perioperative administration of n-3 fatty acids. Br J Nutr. 2002 Jan;87 (Suppl 1):S89–94. doi: 10.1079/bjn2001461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Barbosa VM, Miles EA, Calhau C, Lafuente E, Calder PC. Effects of a fish oil containing lipid emulsion on plasma phospholipid fatty acids, inflammatory markers, and clinical outcomes in septic patients: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Crit Care. Jan 19;14(1):R5. doi: 10.1186/cc8844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Preiser JC, Chiolero R, Wernerman J. Nutritional papers in ICU patients: what lies between the lines? Intensive Care Med. 2003 Feb;29(2):156–166. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1581-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]