This meta-analysis of the literature reveals that imaging findings of spine degeneration are present in high proportions of asymptomatic individuals, increasing with age. Many imaging-based degenerative features are likely part of normal aging and unassociated with pain.

Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE:

Degenerative changes are commonly found in spine imaging but often occur in pain-free individuals as well as those with back pain. We sought to estimate the prevalence, by age, of common degenerative spine conditions by performing a systematic review studying the prevalence of spine degeneration on imaging in asymptomatic individuals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

We performed a systematic review of articles reporting the prevalence of imaging findings (CT or MR imaging) in asymptomatic individuals from published English literature through April 2014. Two reviewers evaluated each manuscript. We selected age groupings by decade (20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80 years), determining age-specific prevalence estimates. For each imaging finding, we fit a generalized linear mixed-effects model for the age-specific prevalence estimate clustering in the study, adjusting for the midpoint of the reported age interval.

RESULTS:

Thirty-three articles reporting imaging findings for 3110 asymptomatic individuals met our study inclusion criteria. The prevalence of disk degeneration in asymptomatic individuals increased from 37% of 20-year-old individuals to 96% of 80-year-old individuals. Disk bulge prevalence increased from 30% of those 20 years of age to 84% of those 80 years of age. Disk protrusion prevalence increased from 29% of those 20 years of age to 43% of those 80 years of age. The prevalence of annular fissure increased from 19% of those 20 years of age to 29% of those 80 years of age.

CONCLUSIONS:

Imaging findings of spine degeneration are present in high proportions of asymptomatic individuals, increasing with age. Many imaging-based degenerative features are likely part of normal aging and unassociated with pain. These imaging findings must be interpreted in the context of the patient's clinical condition.

Low back pain has a high prevalence in industrialized countries, affecting up to two-thirds of adults at some point in their lifetime.1 Back pain is associated with high health care costs and has substantial economic consequences due to loss of productivity from back pain–associated disability.2 Advanced imaging (MR imaging and CT) is increasingly used in the evaluation of patients with low back pain.3 Findings such as disk degeneration, facet hypertrophy, and disk protrusion are often interpreted as causes of back pain, triggering both medical and surgical interventions, which are sometimes unsuccessful in alleviating the patient's symptoms.4 Prior studies have demonstrated that imaging findings of spinal degeneration associated with back pain are also present in a large proportion of asymptomatic individuals.5–7

Given the large number of adults who undergo advanced imaging to help determine the etiology of their back pain, it is important to know the prevalence of imaging findings of degenerative disease in asymptomatic populations. Such information will help both clinical providers and patients interpret the importance of degenerative findings noted in radiology reports. The aim of this study was to systematically review the literature to determine the age-specific prevalence of various imaging findings often associated with degenerative spine disease in asymptomatic individuals. We studied the age-specific prevalence of the following imaging findings in asymptomatic individuals: disk degeneration, disk signal loss, disk height loss, disk bulge, disk protrusion, annular fissures, facet degeneration, and spondylolisthesis.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources and Searches

We performed a comprehensive search for articles describing relevant imaging findings by using MEDLINE and EMBASE. To identify studies on imaging of asymptomatic spinal disorders, we searched 3 databases through April 2014 (week 16): Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, and the Web of Science. Ovid MEDLINE and Ovid EMBASE use controlled vocabulary. EMBASE was searched from 1988 to week 16 of 2014, and MEDLINE was searched from 1946 to 2014. The Web of Science is text word–based but tends to be more current and multidisciplinary, so articles may be discovered that are not included in the other databases. The initial concept was spinal diseases or disorders affecting the spine: intervertebral disk degeneration or displacement, spondylolysis, low back pain, or specific vertebrae and joints (eg, lumbar vertebrae). This was combined with diagnostic imaging techniques (tomography, radiography, MR imaging) and the concept by text words of undetected, asymptomatic, and asymptomatic disease (subject heading available in EMBASE, but not MEDLINE). Details of the search strategy are provided in On-line Tables 1 and 2. Studies identified from the literature search were then further evaluated for inclusion in the meta-analysis. We also searched references from multiple articles to find any additional studies that reported lumbar spine CT or MR imaging findings in individuals without low back pain.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

To be included in our review, a study needed to be published in English and report the prevalence of degenerative findings in different age groups on spine MR imaging or CT in asymptomatic individuals. Asymptomatic individuals were defined as those with no history of back pain. Studies including patients with minor or low-grade back pain were excluded. Studies including patients with motor or sensory symptoms, tumors, or trauma were excluded. If studies did not explicitly state that patients were pain-free, they were excluded. Eleven reviewers (W.B., J.G.J., A.L.A., J.A.T., J.T.W., R.A.D., P.H.L., D.F.K., S.H., L.E.C., and B.W.B.) examined abstracts of studies identified from the literature search to determine whether the articles met the inclusion criteria. For each article that met the inclusion criteria, we used a standard form to abstract imaging technique, age-specific sample sizes, and prevalence rates for the following imaging findings: disk degeneration, disk signal loss (ie, desiccated disk), disk height loss, disk bulge, disk protrusion, annular fissures, facet degeneration, and spondylolisthesis. These entities are defined in detail by the combined task forces of the American Society of Neuroradiology, American Society of Spine Radiology, and North American Spine Society.8 All articles were evaluated by 2 reviewers.

Findings from this systematic review are being used to help physicians with clinical decision-making for patients with low back pain in the Lumbar Imaging With Reporting of Epidemiology: A Pragmatic Cluster Randomized Trial, a multicenter randomized controlled trial aimed at determining whether inserting epidemiologic evidence into lumbar spine imaging reports reduces spine interventions, including further imaging, injections, and surgeries in subsequent years (clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT02015455).

Data Synthesis and Analysis

For each age category and finding, the number of studies that contributed information and approximate patient-level sample size was tabulated. For some studies, only the mean (SD) age was provided, and we therefore used a normal approximation to estimate the number of patients in each age category. For each imaging finding, we fit a generalized linear mixed-effects model for the age-specific prevalence estimate (binomial outcome), clustering on study and adjusting for the midpoint of the reported age interval of each study. If a study reported prevalence estimates across multiple age ranges, we included each age-range-specific estimate as a separate record in the analysis. We examined whether the prevalence estimates varied across patient age by decade (20s, 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s). In each model, we therefore incorporated knots at ages 40 and 60 in an interaction with the age to allow the association between age and prevalence to differ among age groupings. We tested whether the association between prevalence and age differed by age grouping by using a likelihood ratio test, but we did not observe significant evidence for an interaction and therefore used age as a linear predictor in each model. For each finding, we generated generalized linear mixed-effects model–based prevalence predictions at ages 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, and 80 years. All data analyses were performed by using the R statistics package (Version 3.0.1; http://www.r-project.org).

Results

Literature Search

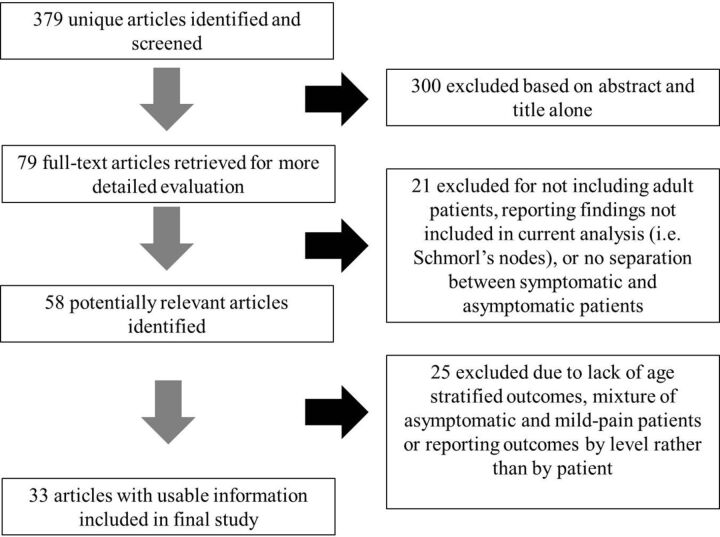

A summary of articles included in the literature review is provided in On-line Table 3. Our search yielded 379 unique articles. On the basis of the abstracts of these articles, we excluded 300 articles that did not meet our review inclusion criteria. Of the remaining 79 articles, we excluded 46 because they did not include asymptomatic individuals or the symptomatic status of patients was ambiguous, did not allow adequate separation of prevalences by age group, or included only patients younger than 18 years of age. Thirty-three studies reporting imaging findings for 3110 individuals met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review. Sample sizes ranged from 8 to 412 individuals. Thirty-two studies reported degenerative changes on MR imaging, and 1 study reported degenerative changes on CT. The search and selection process is summarized in Fig 1.

Fig 1.

Results of literature search.

Age-Specific Prevalence Rates among Asymptomatic Individuals

The estimated number of individuals on which each estimate was made is presented in Table 1. We present age-specific prevalence estimates among asymptomatic individuals in Table 2. Disk degeneration prevalence ranged from 37% of asymptomatic individuals 20 years of age to 96% of those 80 years of age, with a large increase in the prevalence through 50 years. Disk signal loss (“black disk”) was similarly present in more than half of individuals older than 40 years of age, and by 60 years, 86% of individuals had disk signal loss. Disk height loss and disk bulge were moderately prevalent among younger individuals, and prevalence estimates for these findings increased steadily by approximately 1% per year. Disk protrusion and annular fissures were moderately prevalent across all age categories but did not substantially increase with age. Authors rarely reported facet degeneration in younger individuals (4%–9% in those 20 and 30 years of age), but the prevalence increased sharply with age. Spondylolisthesis was not commonly found in asymptomatic individuals until 60 years, when prevalence was 23%; prevalence increased substantially at 70 and 80 years of age.

Table 1:

Estimated number of patients by age used to inform prevalence of degenerative spine imaging findings in asymptomatic patientsa

| Imaging Finding | Age (yr) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | |

| Disk degeneration | 273 (9) | 604 (16) | 415 (12) | 311 (10) | 80 (4) | 20 (2) | 19 (2) |

| Disk signal loss | 46 (2) | 142 (5) | 352 (4) | 73 (2) | 35 (1) | 15 (1) | 14 (1) |

| Disk height loss | 15 (1) | 163 (5) | 186 (5) | 208 (5) | 35 (1) | 15 (1) | 14 (1) |

| Disk bulge | 55 (4) | 101 (7) | 151 (8) | 123 (7) | 66 (5) | 24 (3) | 22 (3) |

| Disk protrusion | 87 (5) | 468 (14) | 490 (14) | 363 (12) | 86 (5) | 19 (2) | 17 (2) |

| Annular fissure | 167 (5) | 350 (5) | 426 (7) | 53 (3) | 35 (3) | 15 (1) | 14 (1) |

| Facet degeneration | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 596 (3) | 53 (3) | 35 (3) | 15 (1) | 14 (1) |

| Spondylolisthesis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 31 (1) | 53 (1) | 35 (1) | 15 (1) | 14 (1) |

The number of studies are in parentheses.

Table 2:

Age-specific prevalence estimates of degenerative spine imaging findings in asymptomatic patientsa

| Imaging Finding | Age (yr) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | |

| Disk degeneration | 37% | 52% | 68% | 80% | 88% | 93% | 96% |

| Disk signal loss | 17% | 33% | 54% | 73% | 86% | 94% | 97% |

| Disk height loss | 24% | 34% | 45% | 56% | 67% | 76% | 84% |

| Disk bulge | 30% | 40% | 50% | 60% | 69% | 77% | 84% |

| Disk protrusion | 29% | 31% | 33% | 36% | 38% | 40% | 43% |

| Annular fissure | 19% | 20% | 22% | 23% | 25% | 27% | 29% |

| Facet degeneration | 4% | 9% | 18% | 32% | 50% | 69% | 83% |

| Spondylolisthesis | 3% | 5% | 8% | 14% | 23% | 35% | 50% |

Prevalence rates estimated with a generalized linear mixed-effects model for the age-specific prevalence estimate (binomial outcome) clustering on study and adjusting for the midpoint of each reported age interval of the study.

Discussion

This systematic review indicates that many imaging findings of degenerative spine disease have a high prevalence among asymptomatic individuals. All imaging findings examined in this review had an increasing prevalence with increasing age, and some findings (disk degeneration and signal loss) were present in nearly 90% of individuals 60 years of age or older. Our study suggests that imaging findings of degenerative changes such as disk degeneration, disk signal loss, disk height loss, disk protrusion, and facet arthropathy are generally part of the normal aging process rather than pathologic processes requiring intervention. The finding that >50% of asymptomatic individuals 30–39 years of age have disk degeneration, height loss, or bulging suggests that even in young adults, degenerative changes may be incidental and not causally related to presenting symptoms. The results from this systematic review strongly suggest that when degenerative spine findings are incidentally seen (ie, as part of imaging for an indication other than pain or an incidental disk herniation at a level other than where a patient's pain localizes), these findings should be considered as normal age-related changes rather than pathologic processes.

MR imaging is highly sensitive in detecting the degenerative changes examined in our study.9 However, even among patients with back pain, prior studies have demonstrated that degenerative findings on MR imaging are not necessarily associated with the degree or the presence of low back pain. Berg et al10 found that a composite MR imaging score taking into account Modic changes, posterior high intensity zones, disk signal changes, and disk height decrease was not correlated with disability or the intensity of low back pain in 170 disk prosthesis candidates. Takatalo et al11 found that disk herniations were strongly associated with low back pain severity among 554 young adults. However, annular fissures, high-intensity zone lesions, Modic changes, and spondylotic defects were not associated with low back pain severity.11 They also demonstrated that disk degeneration was found in one-third of asymptomatic 21-year-olds.11 A systematic review of 12 studies found no consistent association between low back pain and MR imaging findings of Modic changes, disk degeneration, and disk herniation.12 In a large case control study, vertebral endplate changes were not associated with chronic low back pain.13 A number of studies of elite athletes have also demonstrated no association between degenerative changes on MR imaging and the presence or degree of low back pain.14,15 Systematic reviews on the prognostic role of MR imaging findings for outcomes of conservative back pain therapies have failed to find an association between imaging findings and clinical outcomes.16,17 Perhaps most important, the relationship between imaging findings and surgical outcomes has not been well established.18,19 This literature, combined with the results of our study, highlights the importance of caution and of knowledge of the prevalence of imaging findings in similarly aged asymptomatic individuals when interpreting the clinical significance of imaging findings in patients with low back pain.

A number of previously published studies have demonstrated the increasing prevalence of degenerative spine findings with increasing age in asymptomatic patients.1,5,20 A cross-sectional study of 975 individuals (symptomatic and asymptomatic) found that the prevalence of an intervertebral disk space with disk degeneration increased from approximately 70% of individuals younger than 50 years of age to >90% of individuals older than 50 years of age.21 These findings are largely consistent with the findings of our study. Some prior studies have failed to demonstrate an association between degenerative spine disease and low back pain.22,23 With a prevalence of degenerative findings of >90% in asymptomatic individuals 60 years of age or older, our study supports the hypothesis that degenerative changes observed on CT and MR imaging are often seen with normal aging. The substantial variation in the prevalence of degenerative findings between age groups of asymptomatic individuals highlights the importance of establishing further diagnostic criteria to help distinguish age-related degenerative changes from pathologic, pain-generating degenerative changes.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Many of the individuals included in the studies of this systematic review were recruited as volunteers. This recruitment could lead to selection bias because these volunteers are not necessarily representative of the general population. Another limitation is that many studies included in this analysis did not use multiple observers, and it is difficult to ascertain inter- and intraobserver agreement for the presence of these degenerative findings on MR imaging. Recently published studies have demonstrated that even with standardization of nomenclature, interobserver variability is moderate at best.24,25 Furthermore, the studies included in this review span >25 years and did not always use standard nomenclature. Imaging findings were not stratified by the degree of severity. It is possible that asymptomatic individuals have less severe degenerative changes than those with symptoms. Our study does not imply or conclude that the above-mentioned degenerative findings are always age-related rather than pathologic. Our study applies more to cases in which such degenerative findings are incidentally seen in the evaluation of patients without low back pain or findings are found at a level that does not correlate with findings on physical examination. The data on which the systematic review is based may be affected by publication bias.26 Despite the limitations of this study, this systematic review provides useful data to share with clinicians and patients when explaining the clinical significance of degenerative findings seen on advanced imaging.

Conclusions

Imaging evidence of degenerative spine disease is common in asymptomatic individuals and increases with age. These findings suggest that many imaging-based degenerative features may be part of normal aging and unassociated with low back pain, especially when incidentally seen. These imaging findings must be interpreted in the context of the patient's clinical condition.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Disclosures: Bryan Comstock—RELATED: Grant: National Institutes of Health.* Patrick H. Luetmer—RELATED: Grant: National Institutes of Health.* Brian W. Bresnahan—RELATED: Grant: National Institutes of Health,* Comments: Co-Investigator and institution received federally negotiated F&A compensation; UNRELATED: Grants/Grants Pending: University of Washington, Comments: education and research grants related to radiology, economics, health services research, and comparative effectiveness research as a career and profession, though no other specific grants related to inserting text in radiology reports; previous research grant with GE Healthcare related to risk and benefit assessment for CT imaging, with a focus on radiation-exposure mitigation strategies; Other: I pay United States taxes and Washington state taxes as an employed US citizen, resulting in known and unknown compensation, subsidies, and expenditures. Richard A. Deyo—RELATED: Grant: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality*; UNRELATED: Board Membership: Informed Medical Decisions Foundation (nonprofit foundation in Boston); Grants/Grants Pending: National Institutes of Health,* Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,* Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute,* Comments: multiple current and pending grants related to back pain research; Royalties: UpToDate, Comments: for authoring topics on low back pain for this on-line reference source. Judith A. Turner—RELATED: Grant: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.* Kathryn James—RELATED: Grant: National Institutes of Health*; Support for Travel to Meetings for the Study or Other Purposes: National Institutes of Health,* Comments: The grant supported travel for site visits. David F. Kallmes—RELATED: Grant: National Institutes of Health,* Micrus, Comments: research support for clinical trial; UNRELATED: Grants/Grants Pending: ev3,* NFocus,* Sequent,* MicroVention,* Cook,* ArthroCare,* CareFusion,* Comments: research support; Payment for Development of Educational Presentations: CareFusion,* eV3.* Jeffrey G. Jarvik—RELATED: Grant: National Institutes of Health*; Support for Travel to Meetings for the Study or Other Purposes: National Institutes of Health Health Care Systems Collaboratory meetings; UNRELATED: Board Membership: GE Healthcare CER Advisory Board, Comments: past activity, ended October 2012; Consultancy: HealthHelp (a radiology benefits management company); Grants/Grants Pending: National Institutes of Health,* Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality,* Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute*; Patents (planned, pending or issued): PhysiSonics* (an ultrasound-based diagnostic company); Royalties: PhysiSonics*; Stock/Stock Options: PhysiSonics; Travel/Accommodations/Meeting Expenses Unrelated to Activities Listed: GE-Association of University Radiologists Radiology Research Academic Fellowship, Comments: I serve on the academic advisory board. *Money paid to the institution.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant UH3 4UH3AR066795-02.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jarvik JG, Deyo RA. Diagnostic evaluation of low back pain with emphasis on imaging. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:586–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Deyo RA, Cherkin D, Conrad D, et al. Cost, controversy, crisis: low back pain and the health of the public. Annu Rev Public Health 1991;12:141–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li AL, Yen D. Effect of increased MRI and CT scan utilization on clinical decision-making in patients referred to a surgical clinic for back pain. Can J Surg 2011;54:128–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carragee E, Alamin T, Cheng I, et al. Are first-time episodes of serious LBP associated with new MRI findings? Spine J 2006;6:624–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, et al. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects: a prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990;72:403–08 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kalichman L, Kim DH, Li L, et al. Computed tomography-evaluated features of spinal degeneration: prevalence, intercorrelation, and association with self-reported low back pain. Spine J 2010;10:200–08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wiesel SW, Tsourmas N, Feffer HL, et al. A study of computer-assisted tomography. I. The incidence of positive CAT scans in an asymptomatic group of patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1984;9:549–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fardon DF, Milette PC. Nomenclature and classification of lumbar disc pathology: recommendations of the combined task forces of the North American Spine Society, American Society of Spine Radiology, and American Society of Neuroradiology. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:E93–E113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sasiadek MJ, Bladowska J. Imaging of degenerative spine disease–the state of the art. Adv Clin Exp Med 2012;21:133–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Berg L, Hellum C, Gjertsen O, et al. Do more MRI findings imply worse disability or more intense low back pain? A cross-sectional study of candidates for lumbar disc prosthesis. Skeletal Radiol 2013;42:1593–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Takatalo J, Karppinen J, Niinimäki J, et al. Association of Modic changes, Schmorl's nodes, spondylolytic defects, high-intensity zone lesions, disc herniations, and radial tears with low back symptom severity among young Finnish adults. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37:1231–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Steffens D, Hancock MJ, Maher CG, et al. Does magnetic resonance imaging predict future low back pain? A systematic review. Eur J Pain 2014;18:755–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kovacs FM, Arana E, Royuela A, et al. Vertebral endplate changes are not associated with chronic low back pain among Southern European subjects: a case control study. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012;33:1519–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaneoka K, Shimizu K, Hangai M, et al. Lumbar intervertebral disk degeneration in elite competitive swimmers: a case control study. Am J Sports Med 2007;35:1341–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kraft CN, Pennekamp PH, Becker U, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging findings of the lumbar spine in elite horseback riders: correlations with back pain, body mass index, trunk/leg-length coefficient, and riding discipline. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:2205–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Modic MT, Obuchowski NA, Ross JS, et al. Acute low back pain and radiculopathy: MR imaging findings and their prognostic role and effect on outcome. Radiology 2005;237:597–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chou R, Fu R, Carrino JA, et al. Imaging strategies for low-back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2009;373:463–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Carlisle E, Luna M, Tsou PM, et al. Percent spinal canal compromise on MRI utilized for predicting the need for surgical treatment in single-level lumbar intervertebral disc herniation. Spine J 2005;5:608–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lurie JD, Moses RA, Tosteson AN, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging predictors of surgical outcome in patients with lumbar intervertebral disc herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38:1216–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Greenberg JO, Schnell RG. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic adults: cooperative study—American Society of Neuroimaging. J Neuroimaging 1991;1:2–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Teraguchi M, Yoshimura N, Hashizume H, et al. Prevalence and distribution of intervertebral disc degeneration over the entire spine in a population-based cohort: the Wakayama Spine Study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2014;22:104–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jarvik JJ, Hollingworth W, Heagerty P, et al. The Longitudinal Assessment of Imaging and Disability of the Back (LAIDBack) study: baseline data. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:1158–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jarvik JG, Hollingworth W, Heagerty PJ, et al. Three-year incidence of low back pain in an initially asymptomatic cohort: clinical and imaging risk factors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:1541–48; discussion 1549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arana E, Kovacs FM, Royuela A, et al. Influence of nomenclature in the interpretation of lumbar disk contour on MR imaging: a comparison of the agreement using the combined task force and the Nordic nomenclatures. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2011;32:1143–48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Arana E, Royuela A, Kovacs FM, et al. Lumbar spine: agreement in the interpretation of 1.5-T MR images by using the Nordic Modic Consensus Group classification form. Radiology 2010;254:809–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Thornton A, Lee P. Publication bias in meta-analysis: its causes and consequences. J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:207–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boden SD, Riew KD, Yamaguchi K, et al. Orientation of the lumbar facet joints: association with degenerative disc disease. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996;78:403–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Boos N, Rieder R, Schade V, et al. 1995 Volvo Award in clinical sciences: the diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging, work perception, and psychosocial factors in identifying symptomatic disc herniations. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:2613–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Capel A, Medina FS, Medina D, et al. Magnetic resonance study of lumbar disks in female dancers. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:1208–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Danielson B, Willen J. Axially loaded magnetic resonance image of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic individuals. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:2601–06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dora C, Walchli B, Elfering A, et al. The significance of spinal canal dimensions in discriminating symptomatic from asymptomatic disc herniations. Eur Spine J 2002;11:575–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Edmondston SJ, Song S, Bricknell RV, et al. MRI evaluation of lumbar spine flexion and extension in asymptomatic individuals. Man Ther 2000;5:158–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Erkintalo MO, Salminen JJ, Alanen AM, et al. Development of degenerative changes in the lumbar intervertebral disk: results of a prospective MR imaging study in adolescents with and without low-back pain. Radiology 1995;196:529–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Feng T, Zhao P, Liang G. Clinical significance on protruded nucleus pulposus: a comparative study of 44 patients with lumbar intervertebral disc protrusion and 73 asymptomatic controls in tridimentional computed tomography [in Chinese]. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi 2000;20:347–49 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gibson MJ, Szypryt EP, Buckley JH, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of adolescent disc herniation. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1987;69:699–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hamanishi C, Kawabata T, Yosii T, et al. Schmorl's nodes on magnetic resonance imaging. Their incidence and clinical relevance. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1994;19:450–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Healy JF, Healy BB, Wong WH, et al. Cervical and lumbar MRI in asymptomatic older male lifelong athletes: frequency of degenerative findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1996;20:107–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med 1994;331:69–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kanayama M, Togawa D, Takahashi C, et al. Cross-sectional magnetic resonance imaging study of lumbar disc degeneration in 200 healthy individuals. J Neurosurg Spine 2009;11:501–07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Karakida O, Ueda H, Ueda M, et al. Diurnal T2 value changes in the lumbar intervertebral discs. Clin Radiol 2003;58:389–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kjaer P, Leboeuf-Yde C, Korsholm L, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and low back pain in adults: a diagnostic imaging study of 40-year-old men and women. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:1173–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kovacs FM, Arana E, Royuela A, et al. Disc degeneration and chronic low back pain: an association which becomes nonsignificant when endplate changes and disc contour are taken into account. Neuroradiology 2014;56:25–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Matsumoto M, Okada E, Toyama Y, et al. Tandem age-related lumbar and cervical intervertebral disc changes in asymptomatic subjects. Eur Spine J 2013;22:708–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Paajanen H, Erkintalo M, Parkkola R, et al. Age-dependent correlation of low-back pain and lumbar disc degeneration. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1997;116:106–07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Paajanen H, Erkintalo M, Kuusela T, et al. Magnetic resonance study of disc degeneration in young low-back pain patients. Spine 1989;14:982–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ranson CA, Kerslake RW, Burnett AF, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic professional fast bowlers in cricket. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005;87:1111–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Savage RA, Whitehouse GH, Roberts N. The relationship between the magnetic resonance imaging appearance of the lumbar spine and low back pain, age and occupation in males. Eur Spine J 1997;6:106–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Silcox DH 3rd, Horton WC, Silverstein AM. MRI of lumbar intervertebral discs: diurnal variations in signal intensities. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995;20:807–11; discussion 811–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stadnik TW, Lee RR, Coen HL, et al. Annular tears and disk herniation: prevalence and contrast enhancement on MR images in the absence of low back pain or sciatica. Radiology 1998;206:49–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Szypryt EP, Twining P, Mulholland RC, et al. The prevalence of disc degeneration associated with neural arch defects of the lumbar spine assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1989;14:977–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Weinreb JC, Wolbarsht LB, Cohen JM, et al. Prevalence of lumbosacral intervertebral disk abnormalities on MR images in pregnant and asymptomatic nonpregnant women. Radiology 1989;170:125–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Weishaupt D, Zanetti M, Hodler J, et al. MR imaging of the lumbar spine: prevalence of intervertebral disk extrusion and sequestration, nerve root compression, end plate abnormalities, and osteoarthritis of the facet joints in asymptomatic volunteers. Radiology 1998;209:661–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zobel BB, Vadalà G, Del Vescovo R, et al. T1rho magnetic resonance imaging quantification of early lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration in healthy young adults. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2012;37:1224–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.