Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to further examine the utility of mucin expression profiles as prognostic factors in PDAC.

Methods

Mucin (MUC) expression was examined by immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) specimens obtained from 114 patients with PDAC. The rate of expression of each mucin was compared with clinicopathologic features.

Results

The expression rates of mucins in cancer lesions were MUC1, 87.7%; MUC2, 0.8%; MUC4, 93.0%; MUC5AC, 78.9%; MUC6, 24.6%; and MUC16, 67.5%. MUC1 and MUC4 were positive and MUC2 was negative in most PDACs. Patients with advanced stage of PDAC with MUC5AC expression had a significantly better outcome than those who were MUC5AC-negative (P=0.002).With increasing clinical stage, total MUC6 expression decreased (P for trend=0.001) and MUC16 cytoplasmic expression increased (P for trend=0.02). The prognosis of patients with MUC16 cytoplasmic expression was significantly poorer than those without this expression. Multivariate survival analysis revealed that MUC16 cytoplasmic expression was a significant independent predictor of a poor prognosis after adjusting for the effects of other prognostic factors (P=0.002).

Conclusion

Mucin expression profiles in EUS-FNA specimens have excellent diagnostic utility and are useful predictors of outcome in patients with PDAC.

Keywords: MUC, pancreas, carcinoma, prognosis, FNA

INTRODUCTION

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a lethal malignancy with a poor prognosis in most patients due to therapeutic resistance and frequent recurrence1. Diagnosis of PDAC can be achieved safely using mucin expression profiles in pancreatic specimens obtained using Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) 2. Mucins play crucial roles in carcinogenesis and tumor invasion, and MUC1 (pan-epithelial membrane mucin), the first cloned mucin, is an important human tumor antigen 3,4,5. MUC1 is one of the comprehensive candidate proteins as a target for cancer vaccines6.

Our immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies of mucin expression profiles in pancreatic neoplasms 7,8 have shown that high expression of MUC1 is observed in PDACs and is related to a poor outcome9 -11 ; intestinal-type IPMNs are MUC1-negative but MUC2 (intestinal secretory mucin)-positive, and may show invasive growth with de novo MUC1 expression; gastric-type IPMNs that are MUC1-negative and MUC2-negative have low malignant potential10-12; de novo high MUC4 (tracheobronchial membrane mucin) expression is associated with a poor outcome in PDAC 11; and MUC4 expression mainly in intestinal-type IPMNs13. Haridas et al. showed that MUC16 expression is also associated with a poor outcome in PDAC 14 and we have found an association of MUC16 expression with a poor outcome in cholangiocellular carcinoma15.

In the present study, we show that mucin expression profiles in EUS-FNA specimens are useful for diagnosis and prognostic prediction of outcome in patients with PDAC.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

All tissue specimens were retrieved from the files of the Division of Surgical Pathology, Kagoshima University Hospital during the period from 2007 to 2012. A total of 114 out of 196 cases of PDAC had adequate cellular material for further IHC examination. The study was conducted in accordance with the guiding principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Collection of samples was approved by the ethical committee of Kagoshima University Hospital and informed written consent was obtained from each patient. All studies using human materials in this article were approved by the ethical committee of Kagoshima University Hospital (revised 22-127).

The mean age of the patients was 67.4 years old (range: 41-85 years old). Clinical TNM (cTNM) classifications were retrieved from medical records. Of the 114 patients, 14 were treated by pancreaticoduodenectomy or distal pancreatectomy after EUS-FNA biopsy examination. The other 100 patients did not undergo surgery due to the cancer being in an inoperable advanced stage. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy only, radiotherapy only, and neoadjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy were administrated in 56, 3, and 32 patients, respectively.

Immunohistochemistry

All specimens were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin and cut into 4-μm thick serial sections for IHC, in addition to hematoxylin and eosin staining. We used the following monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) for IHC: anti-MUC1 MAb clone DF3 (mouse IgG, Toray-Fuji Bionics, Tokyo, Japan); anti-MUC2 MAb clone Ccp58 (mouse IgG, Novocastra Reagents, Leica Biosystems, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK); anti-MUC4 MAb clone 8G7 [(mouse IgG, generated by one of us (S. K. B.)), anti-MUC5AC MAb clone CLH2 (mouse IgG, Novocastra Reagents), anti-MUC6 MAb clone CLH5 (mouse IgG, Novocastra Reagents), and anti-MUC16 MAb clone M11 (mouse IgG, Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). IHC was performed by the immunoperoxidase method as follows. Antigen retrieval was achieved using CC1 antigen retrieval buffer (pH8.5 EDTA, 100 °C, 30 min, Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA) for all sections. The sections were incubated with a primary antibody (dilutions and other conditions: DF3 1:50, 37°C, 32 min; Ccp58 1:200, 37°C, 24 min; 8G7 1:3000, 37°C, 32 min; CLH2 1:100, 37°C, 24 min; CLH5 1:100, 37°C, 24 min; OC125 1:100, 37°C, 24 min) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4 with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and stained on a Benchmark XT automated slide stainer using a diaminobenzidine detection kit (UltraView DAB, Ventana Medical Systems). Control staining using normal mouse serum or PBS-BSA instead of a primary antibody showed no reactivity.

Evaluation of immunohistochemical results

Four blinded investigators (M.H., Y.G., I.K., T.H. and S.Y.) evaluated the IHC staining data independently. When the evaluation differed among the four, a final decision was made by consensus. “Membranous expression” and “cytoplasmic expression” were observed independently, and the expression rate was based on the dominant expression pattern. The carcinoma cells were considered to be positive when at least one of these components was positive. The IHC results were evaluated using the percentage of positively stained carcinoma cells. IHC staining was considered positive if ≥10% of carcinoma cells were stained and negative if <10% of the cells were stained.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JMP® 10.0.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Comparison of each mucin expression rate with clinicopathologic features was performed by chi-square test or Fisher exact test as appropriate. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for subgroups based on mucin expression status were drawn using death as the endpoint. Differences in the clinical prognosis between subgroups were examined by the log-rank test. Univariate and multivariate survival analyses were also performed using Cox proportional hazard models. A Cox proportional hazard analysis was used to estimate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals with adjustment for the effects of other clinicopathologic factors. A probability of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Expression profiles of mucins

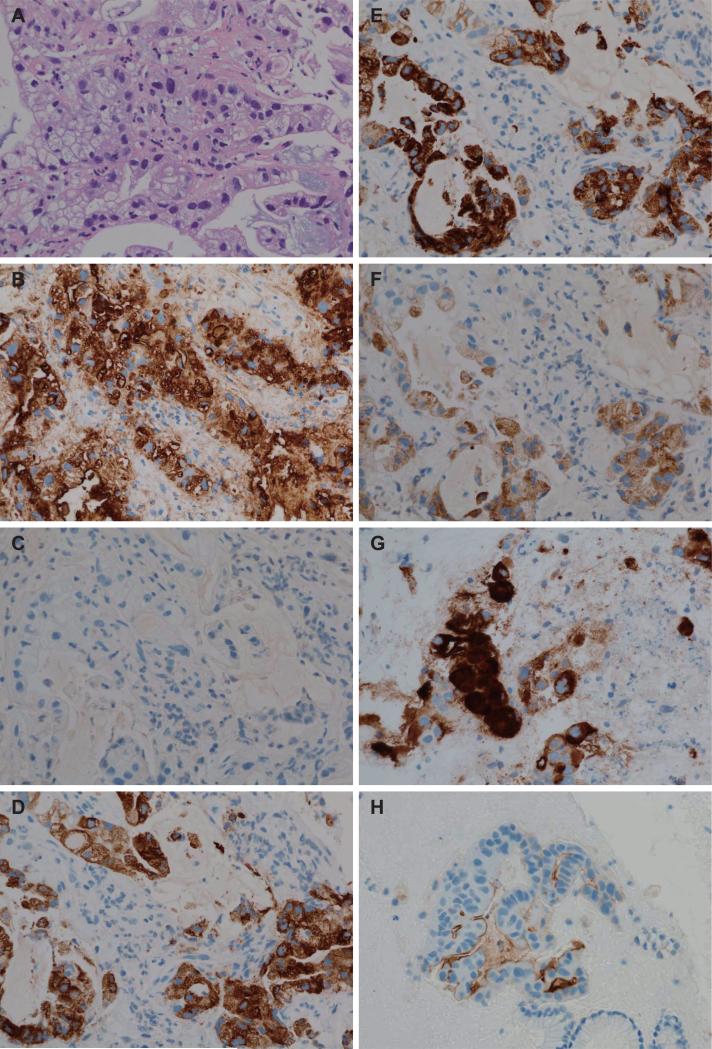

Representative pattern of mucin expression in EUS-FNA specimens is shown in Figure 1. The positive expression rates in cancer lesions (≥10% of carcinoma cells stained) were MUC1, 87.7% (100/114); MUC2, 0.8% (1/114); MUC4, 93.0% (106/114); MUC5AC, 78.9% (90/114); MUC6, 24.6% (28/114), and MUC16, 67.5%(77/114).

Figure 1.

Representative microscopic features in endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) specimens. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin staining shows atypical epithelial cells composed of irregular tubular structures. (B) MUC1 is expressed in cell apexes and/or cytoplasm of carcinoma cells. (C) MUC2 is not expressed in cell apexes or cytoplasm of carcinoma cells. (D) MUC4 is expressed in cytoplasm of carcinoma cells. (E) MUC5AC is expressed in cytoplasm of carcinoma cells. (F) MUC6 is expressed in the cytoplasm of carcinoma cells. (G) MUC16 is expressed in membrane and cytoplasm of carcinoma cells in this specimen. (H) MUC16 is expressed only in the membrane of carcinoma cells in this specimen.

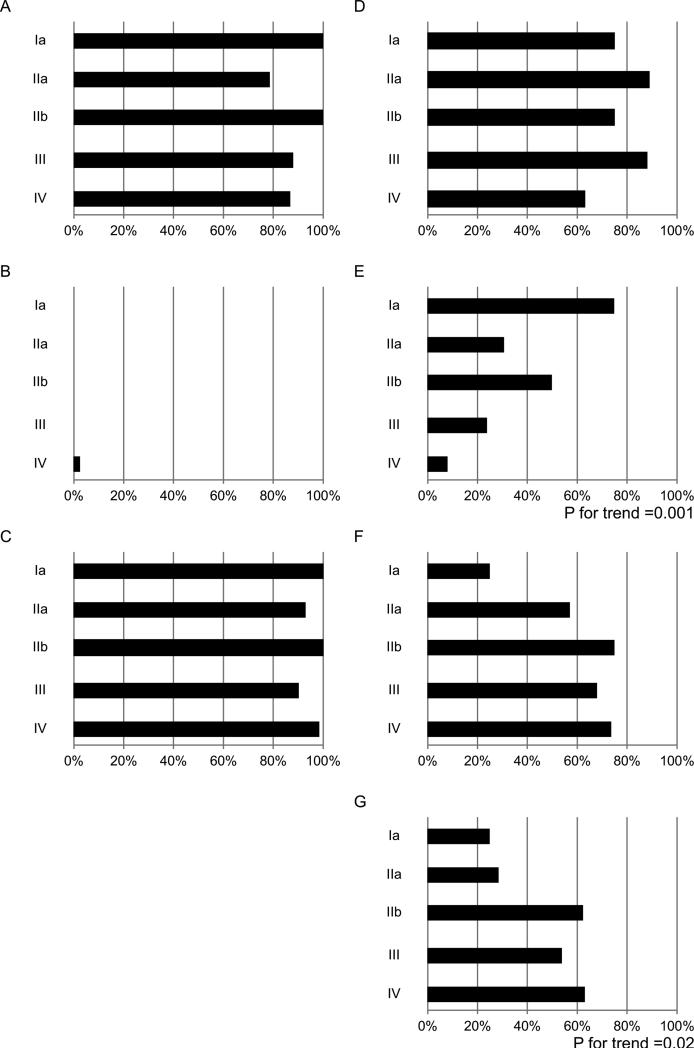

Relationships between mucin expression and clinicopathologic features are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 2. MUC1-positive, MUC2-negative and MUC4-positive expression showed no relationship with any clinicopathologic features, since MUC1 and MUC4 were positive and MUC2 negative in most PDAC cases. (Table 1; Figure 2A, 2B, 2C).

Table 1.

Summary of the Mucin Expression based on Clinicopathological Features of invasive pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

| Category | No. patients (%) | MUC1 Negative <10% | Positive ≥10% | P | MUC2 Negative <10% | Positive ≥10% | P | MUC4 Negative <10% | Positive ≥10% | P | MUC5AC Negative (%) | Positive <10% | P | MUC6 Negative <10% | Positive ≥10% | P | MUC16t Negative <10% | Positive ≥10% | P | MUC16c Negative <10% | Positive ≥10% | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age(yrs) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| <65 | 68 (59.7) | 9(13.2) | 59(86.8) | 0.70 | 67(98.5) | 1(1.5) | 0.60 | 5 (7.4) | 63 (92.6) | 0.70 | 14(20.6) | 54(79.4) | 0.88 | 52(76.5) | 16(23.5) | 0.76 | 19(27.9) | 49(72.1) | 0.21 | 31(45.6) | 37(54.4) | 0.81 |

| ≥65 | 46 (40.3) | 5(10.9) | 41(89.1) | 46(100) | 0(0) | 3 (6.5) | 43 (93.5) | 10(21.7) | 36(78.3) | 34(73.9) | 12(26.1) | 18(39.1) | 28(60.9) | 22(47.8) | 24(52.1) | |||||||

| Gender | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Men | 62(54.4) | 6(9.7) | 56(90.3) | 0.36 | 61(98.4) | 1(1.6) | 0.27 | 3(4.8) | 59(95.2) | 0.47 | 12(19.4) | 50(80.6) | 0.63 | 48(77.4) | 14(22.6) | 0.59 | 18(29.0) | 44(71.0) | 0.39 | 29(46.8) | 33(53.2) | 0.95 |

| Women | 52(45.6) | 8(15.4) | 44(84.6) | 52(100) | 0(0) | 5(9.6) | 47(90.4) | 12(23.1) | 40(76.9) | 38(73.1) | 14(26.9) | 19(36.5) | 33(63.5) | 24(46.2) | 28(53.8) | |||||||

| Location | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Head | 68 (59.7) | 9(13.2) | 59(86.8) | 0.70 | 67(98.5) | 1(1.5) | 0.60 | 5 (7.4) | 63 (92.6) | 0.70 | 15(23.4) | 49(76.6) | 0.48 | 47(73.4) | 17(26.6) | 0.57 | 26(40.6) | 38(59.4) | 0.03* | 36(56.3) | 28(43.7) | 0.02* |

| Body/tail | 46 (40.3) | 5(10.9) | 41(89.1) | 46(100) | 0(0) | 3 (6.5) | 43 (93.5) | 9(18.0) | 41(82.0) | 39(78.0) | 11(22.0) | 11(22.0) | 39(78.0) | 17(34.0) | 33(66.0) | |||||||

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| <4 | 73(64.0) | 10(13.7) | 63(86.3) | 0.77 | 40(97.6) | 1(2.4) | 0.36 | 4(5.5) | 69(94.5) | 0.46 | 12(16.4) | 61(83.6) | 0.11 | 51(69.9) | 22(30.1) | 0.06 | 27(37.0) | 46(63.0) | 0.16 | 36(49.3) | 37(50.4) | 0.42 |

| ≥4 | 41(36.0) | 4(9.8) | 37(90.2) | 73(100) | 0(0) | 4(9.8) | 37(90.2) | 12(29.3) | 29(70.7) | 35(85.4) | 6(14.6) | 10(24.4) | 31(75.6) | 17(41.5) | 24(58.5) | |||||||

| cT | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| T1, T2 | 4 (3.5) | 0(0) | 4(100) | 1.0 | 4(100) | 0(0) | 1.0 | 0(0) | 4(100) | 1.0 | 1(25.0) | 3(75.0) | 1.0 | 1(25.0) | 3(75.0) | 0.045* | 3(75.0) | 1(25.0) | 0.10 | 3(75.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0.34 |

| T3, T4 | 110(96.5) | 14(12.7) | 96(87.3) | 109(99.1) | 1(0.9) | 8(7.3) | 102(92.7) | 23(20.9) | 87(79.1) | 85(77.3) | 25(22.7) | 34(30.9) | 76(69.1) | 50(45.5) | 60(54.5) | |||||||

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Negative | 68(59.6) | 8(11.8) | 60(88.2) | 0.84 | 67(98.5) | 1(1.5) | 1.0 | 5(7.4) | 63(92.6) | 1.0 | 15(22.1) | 53(77.9) | 0.75 | 50(73.5) | 18(26.5) | 0.56 | 24(35.3) | 44(64.7) | 0.43 | 34(50.0) | 34(50.0) | 0.36 |

| Positive | 46(40.6) | 6(13.0) | 40(87.0) | 46(100) | 0(0) | 3(6.5) | 43(93.5) | 9(19.6) | 37(80.4) | 36(78.3) | 10(21.7) | 13(28.3) | 33(71.3) | 19(41.3) | 27(58.7) | |||||||

| cM | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Negative | 76(66.7) | 9(11.8) | 67(88.2) | 0.84 | 76(100) | 0(0) | 0.33 | 7(9.2) | 69(90.7) | 0.27 | 10(13.2) | 66(86.8) | 0.003* | 52(68.4) | 24(31.6) | 0.02* | 27(35.5) | 49(64.5) | 0.32 | 39(51.3) | 37(48.7) | 0.14 |

| Positive | 38(33.3) | 5(13.2) | 33(86.8) | 37(97.4) | 1(2.6) | 1(2.6) | 37(97.4) | 14(36.8) | 24(63.2) | 34(89.5) | 4(10.5) | 10(26.3) | 28(73.7) | 14(36.8) | 24(63.2) | |||||||

| cStage | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| I, II | 26(22.8) | 3(11.5) | 23(88.5) | 1.0 | 26(100) | 0(0) | 1.0 | 1(3.9) | 25(96.1) | 0.68 | 4(15.4) | 24(84.6) | 0.59 | 14(53.9) | 12(46.2) | 0.003* | 11(42.3) | 15(57.7) | 0.22 | 16(61.5) | 10(38.5) | 0.08 |

| III, IV | 88(77.2) | 11(12.5) | 77(87.5) | 87(98.9) | 1(1.1) | 7(7.8) | 81(92.1) | 20(22.7) | 68(77.3) | 72(81.8) | 16(18.2) | 26(29.6) | 62(70.4) | 37(42.1) | 51(57.9) | |||||||

| Histological type | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| tub | 81(71.0) | 11(13.6) | 70(86.4) | 0.75 | 80(98.8) | 1(1.2) | 1.0 | 6(7.4) | 75(92.6) | 1.0 | 16(19.8) | 65(80.2) | 0.59 | 56(69.1) | 25(30.9) | 0.02* | 31(38.3) | 50(61.7) | 0.04* | 44(54.3) | 37(45.7) | 0.01* |

| por | 33(29.0) | 3(9.1) | 30(90.9) | 33(100) | 0(0) | 2(6.1) | 31(93.9) | 8(24.2) | 25(75.8) | 30(90.9) | 3(30.9) | 6(18.2) | 27(81.8) | 9(27.3) | 24(72.7) | |||||||

MUC16t, total MUC16 expression = membranous and cytoplasmic MUC16 expression; MUC16c, cytoplasmic MUC16 expression

tub, tubular adenocarcinoma; por, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma

Figure 2.

The expression rates of individual mucins in various clinical stage of PDAC. (A) MUC1. (B) MUC2. (C) MUC4. (D) MUC5AC. (E) MUC6. (F) MUC16. (membranous and cytoplasmic expression) (G) MUC16 cytoplasmic expression

Patients with MUC5AC expression had less frequent distant metastasis (P=0.003) (Table 1), although MUC5AC expression showed no relationship with clinical stage (Figure 2D).

MUC6 expression in PDAC showed the following findings: (1) significantly frequent MUC6 expression in localized tumor (cT1 and cT2), early stage (I and II) and well differentiated tumors; (2) a significant decrease in MUC6 expression in the advanced stage; and (3) less frequent distant metastasis in patients with MUC6 expression (Table 1 and Figure 2E).

MUC16 expression was significantly more frequent in PDAC with a pancreas head location (P=0.03) and in cases of well differentiated type (P=0.04) (Table 1). Thus, we examined MUC16 expression in PDACs in more detail by dividing the 114 cases (Figure 3E) into those with (n=61) and without (n=53) MUC16 cytoplasmic expression. The 53 negative cases included 24 with exclusively apical MUC16 expression. This analysis showed that MUC16 cytoplasmic expression was more frequent in PDAC a pancreatic head location (P=0.02) and in well differentiatied cases (P=0.01) (Table 1). MUC16 cytoplasmic expression rates increased with more advanced cancer stage (P for trend=0.02) (Figure 3F).

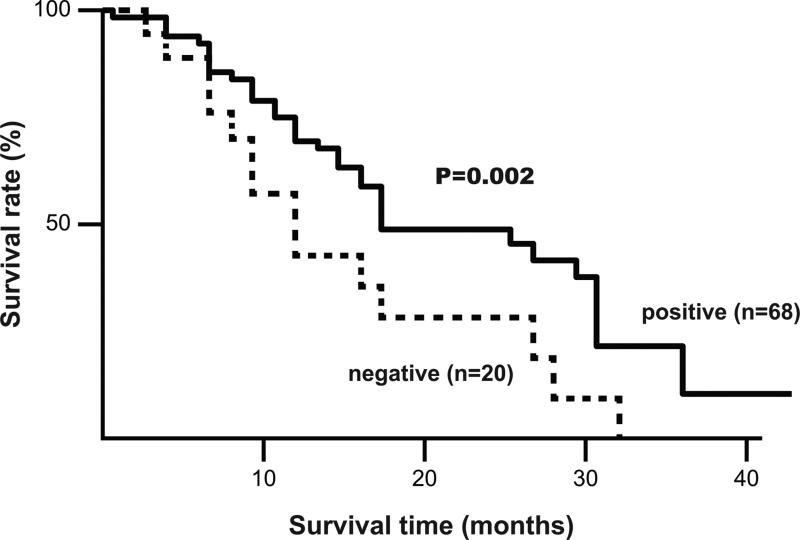

Figure 3.

Correlation between MUC5 expression and cumulative survival rate in 68 patients with PDAC in an advanced stage determined by the Kaplan-Meier method. Survival of patients with MUC5AC expression was better than that for MUC5AC-negative cases (P= 0.002).

Prognostic value of expression of each mucin

Of the 114 patients, 57 died during the follow-up period (0.5-45 months). The median and mean of survival periods were 9.0 and 11.0 months, respectively.

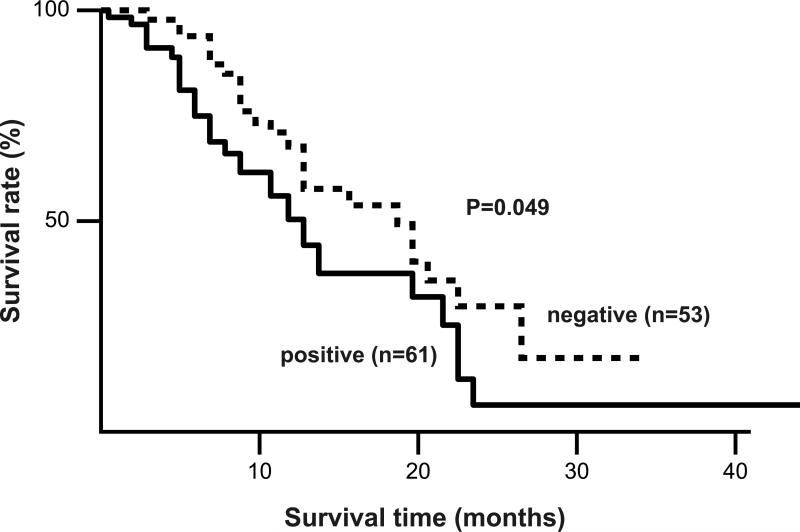

Prognosis was not related to expression of MUC1, MUC2, or MUC4. MUC5AC-positive case in stage III or IV (n=68) had a significantly better prognosis than MUC5AC-negative cases (n=20) (P=0.002, Figure 3). MUC16-positive cases (n=61) had a significantly poorer prognosis compared to those that were MUC16-negative (n=53) (P=0.049 by log-rank test, Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Correlation between MUC16 expression and cumulative survival rate in 114 patients with PDAC determined by the Kaplan-Meier method. Survival of patients with MUC16 expression was worse than that for MUC16 negative (P= 0.049).

Univariate analysis of prognostic factors

The results of univariate analysis of prognostic factors are summarized in Table 2. A large tumor (P=0.005), a tumor location in the pancreatic body or tail (P=0.04), and distant metastasis (P=0.004) were significant factors associated with an unfavorable prognosis in patients with PDAC. Cases with MUC16 cytoplasmic expression had a poorer prognosis than those without such expression (P=0.05).

Table 2.

Results of Survival Analysis by univariate Cox proportional hazard analysis

| Covariate | Death / total | Hazard ratio | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age <65 | 31/ 68 | 1.00 | reference |

| ≥65 | 26 / 46 | 1.08 | 0.63-1.83 |

| Gender Men | 28 / 62 | 1.00 | reference |

| Women | 29 / 52 | 0.73 | 0.43-1.24 |

| Location Head | 27 / 64 | 1.00 | reference |

| Body/tail | 30/ 50 | 0.57 | 0.33-0.96 |

| Tumor size < 4cm | 31/ 73 | 1.00 | reference |

| ≥ 4cm | 26 / 41 | 2.12 | 1.24-3.58 |

| cT T1, T2 | 1 / 4 | 1.00 | reference |

| T3, T4 | 56 / 110 | 3.50 | 0.76-62.11 |

| Lymph node metastasis (-) | 30 / 68 | 1.00 | reference |

| (+) | 27 / 46 | 1.54 | 0.91-2.60 |

| Metastasis (-) | 32 / 76 | 1.00 | reference |

| (+) | 25 / 38 | 2.22 | 1.30-3.75 |

| cStage I, II | 8 / 26 | 1.00 | reference |

| III, IV | 49 / 88 | 1.84 | 0.92-4.22 |

| Histological type tub | 42 / 81 | 1.00 | reference |

| por | 15 / 33 | 1.13 | 0.64-2.12 |

| MUC1 expression (-) | 8 / 14 | 1.00 | reference |

| (+) | 49/ 100 | 0.95 | 0.47-2.18 |

| MUC2 expression (-) | 57 / 113 | 1.00 | reference |

| (+) | 0 / 1 | 1.49e-8 | 0 |

| MUC4 expression (-) | 4 / 8 | 1.00 | reference |

| (+) | 53 / 106 | 1.05 | 0.34-1.10 |

| MUC5 expression (-) | 16 / 24 | 1.00 | reference |

| (+) | 41/ 90 | 0.60 | 0.39-1.84 |

| MUC6 expression (-) | 46 / 86 | 1.00 | reference |

| (+) | 11 / 28 | 0.64 | 0.31-1.20 |

| MUC16t expression (-) | 18 / 37 | 1.00 | reference |

| (+) | 39 / 77 | 1.06 | 0.61-1.92 |

| MUC16c expression (-) | 25 / 53 | 1.00 | reference |

| (+) | 32 / 61 | 1.66 | 0.98-2,84 |

MUC16t, total MUC16 expression = membranous and cytoplasmic MUC16 expression; MUC16c, cytoplasmic MUC16 expression

tub, tubular adenocarcinoma; por, poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma

Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors

The results of multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in PDAC are summarized in Table 3. A large tumor size, distant metastasis, and MUC16 cytoplasmic expression were significant independent predictors of a poor prognosis after adjusting for the effects of other clinicopathologic factors (P=0.002).

Table 3.

Results of survival analysis by multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis

| Covariate | Hazard ratio* | 95% confidence interval* | P value# |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor size | 2.17 | 1.10-4.30 | 0.023 |

| Metastasis | 2.07 | 1.08-3.97 | 0.028 |

| MUC1-positive | 0.66 | 0.26-1.80 | 0.402 |

| MUC2-positive | 5.98e-10 | 0 | 0.182 |

| MUC4-positive | 1.00 | 0.31-4.12 | 0.996 |

| MUC5-positive | 0.81 | 0.41-1.66 | 0.147 |

| MUC6-positive | 0.91 | 0.40-1.91 | 0.81 |

| MUC16t-positive | 0.39 | 0.13-1.06 | 0.06 |

| MUC16c-positive | 3.84 | 1.58-10.7 | 0.002 |

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were obtained using a Cox proportional hazard model with age (continuous), location, cT, lymph node metastasis, cStage, and histological type as covariates.

P values obtained by likelihood ratio test. MUC16t, total MUC16 expression = membranous and cytoplasmic MUC16 expression; MUC16c, cytoplasmic MUC16 expression

DISCUSSION

PDACs were characterized by aberrant expression of transmembrane mucins (MUC1, MUC4, and MUC16) and secretory mucins (MUC2, MUC5AC and MUC6). Most EUS-FNA specimens of PDAC were MUC1-positive, MUC2-negative, and MUC4 positive, and this mucin expression profile may be very useful for a pathological diagnosis of PDAC using very small FNA specimens. The findings for MUC1 and MUC2 are similar to those in previous reports7-10, but the MUC4 positive rate of 87.7% in this study differed from the rate of 32% found in our previous study11. One reason for this discrepancy may be a difference in suitability for prompt fixation between FNA specimens and resected specimens. Another reason may be the stage of the PDAC cases. All specimens in our previous study were surgically removed11, whereas only 14 of the 114 cases in the present study were treated by surgery, with the other 100 patients at an inoperable advanced stage (77.2 % in stage III or IV). The findings of high MUC4 expression as an independent poor prognostic factor in our previous study11 may be related to the high expression rate of MUC4 in the present study.

Overexpression of MUC5AC is associated with poor prognoses in lung adenocarcinoma, cholangiocarcinoma and colorectal cancer16. In contrast, in gastric cancer where MUC5AC is heavily expressed under normal condition, a decrease in MUC5AC during pathologic development from the high expression normal level is associated with a poor prognosis17. Normal pancreatic ductal epithelia show no MUC5AC expression10. In the present study, the prognosis of MUC5AC-positive cases in the advanced stages (stage III and IV) was also significantly better than that of MUC5AC-negative cases. This is an interest observation that requires further study in cases of advanced stage PDAC.

MUC6 expression in PDAC seems to be a favorable factor based on the findings of (1) significantly frequent MUC6 expression in localized, early stage and well differentiated tumors; (2) a significant decrease in MUC6 expression in the advanced stage; and (3) less frequent distant metastasis in patients with MUC6 expression. Leir et al showed that MUC6 may inhibit invasion of tumor cells through the basement membrane of the pancreatic duct and slow the development of infiltrating carcinoma in vitro18. Thus, MUC6 may have a protective function in PDAC.

MUC16 is overexpressed in many malignancies, including ovarian and pancreatic cancer, and cholangiocarcinomas14,15,19 and its overexpression is associated with a poor prognosis. MUC16 is also known as a potential biomarker for the following the response of ovarian cancer to therapy. Lakshmanan et al. have recently established a functional role of MUC16 in the proliferation of breast cancer cells20 and Haridas et al. showed increased expression of MUC16 in progression of pancreatic cancer14. Similarly, in the present study, the prognosis of patients with MUC16 expression was significantly poorer than that of MUC16-negative cases, and the prognosis of patients with MUC16 cytoplasmic expression was also significantly poorer than those without expression. In multivariate analysis of prognostic factors in PDAC, the MUC16 cytoplasmic expression emerged as a significant independent predictors of a poor prognosis along with large tumors and distant metastasis.

In conclusion, our results show that mucin expression profiles in EUS-FNA specimens have excellent diagnostic utilities. MUC1-positive, MUC2-negative and MUC4-positive expression profiles seen in most of PDACs may be useful for pathological diagnosis using small EUS-FNA specimens, whereas MUC5AC, MUC6 and MUC16 expression levels are useful as predictive factors for outcome in patients with PDAC. The patients with PDAC, showing expression pattern MUC5AC-negative, MUC6-negative and/or MUC16 positive, may need only surgical treatment but also chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy called multidisciplinary therapy.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Mr. Kei Matsuo, Ms. Yukari Nishimura, Ms. Sayuri Yoshimura and Ms. Chieko Baba for their excellent technical assistance.

Financial Support

This study was supported in part by Princes Takamatsu Cancer Research Fund to S. Yonezawa; Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) 24590447 to M. Higashi, and Scientific Research (B) 23390085 to S. Yonezawa, and Young Scientists (B) 24701008 to S. Yokoyama from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, Culture and Technology, Japan. S. Batra is supported in part by the NIH grants CA78590, CA163120, CA131944, and CA111294 and M. Jain is supported by P20 GM103480 from the NIH.

List of Abbreviations

- PDAC

Pancreatic ductal cancer

- EUS-FNA

Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- cTNM

clinical TNM classification

- MAb

monoclonal antibody

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None of the authors have a conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Bardeesy N, DePinho RA. Pancreatic cancer biology and genetics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:897–909. doi: 10.1038/nrc949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giorgadze TA, Peterman H, Baloch ZW, et al. Diagnostic utility of mucin profile in fine-needle aspiration specimens of the pancreas: an immunohistochemical study with surgical pathology correlation. Cancer. 2006;108:186–197. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hollingsworth MA, Swanson BJ. Mucins in cancer: protection and control of the cell surface. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:45–60. doi: 10.1038/nrc1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kufe DW. Mucins in cancer: function, prognosis and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:874–885. doi: 10.1038/nrc2761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaur S, Kumar S, Momi N, Sasson AR, Batra SK. Mucins in pancreatic cancer and its microenvironment. Nature reviews. Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2013;10:607–620. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheever MA, Allison JP, Ferris AS, et al. The prioritization of cancer antigens: a national cancer institute pilot project for the acceleration of translational research. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:5323–5337. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yonezawa S, Higashi M, Yamada N, Yokoyama S, Goto M. Significance of mucin expression in pancreatobiliary neoplasms. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2010 Mar;17(2):108–124. doi: 10.1007/s00534-009-0174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yonezawa S, Higashi M, Yamada N, et al. Mucins in human neoplasms: clinical pathology, gene expression and diagnostic application. Pathol Int. 2011;61:697–716. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2011.02734.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Osako M, Yonezawa S, Siddiki B, et al. Immunohistochemical study of mucin carbohydrates and core proteins in human pancreatic tumors. Cancer. 1993;71:2191–2199. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930401)71:7<2191::aid-cncr2820710705>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horinouchi M, Nagata K, Nakamura A, et al. Expression of Different Glycoforms of Membrane Mucin (MUC1) and Secretory Mucin (MUC2, MUC5AC and MUC6) in Pancreatic Neoplasms. Acta Histochemica et Cytochemica. 2003;36:443–453. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saitou M, Goto M, Horinouchi M, et al. MUC4 expression is a novel prognostic factor in patients with invasive ductal carcinoma of the pancreas. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58:845–852. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.023572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakamura A, Horinouchi M, Goto M, et al. New classification of pancreatic intraductal papillary-mucinous tumour by mucin expression: its relationship with potential for malignancy. J Pathol. 2002;197:201–210. doi: 10.1002/path.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitazono I, Higashi M, Kitamoto S, et al. Expression of MUC4 mucin is observed mainly in the intestinal type of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2013;42:1120–1128. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182965915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haridas D, Chakraborty S, Ponnusamy MP, et al. Pathobiological implications of MUC16 expression in pancreatic cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e26839. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higashi M, Yamada N, Yokoyama S, et al. Pathobiological Implications of MUC16/CA125 Expression in Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma-Mass Forming Type. Pathobiology. 2012;79:101–106. doi: 10.1159/000335164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kocer B, Soran A, Erdogan S, et al. Expression of MUC5AC in colorectal carcinoma and relationship with prognosis. Pathol Int. 2002;52:470–477. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1827.2002.01369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim SM, Kwon CH, Shin N, et al. Decreased Muc5AC expression is associated with poor prognosis in gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:114–124. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leir SH, Harris A. MUC6 mucin expression inhibits tumor cell invasion. Experimental cell research. 2011;317:2408–2419. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chauhan SC, Singh AP, Ruiz F, et al. Aberrant expression of MUC4 in ovarian carcinoma: diagnostic significance alone and in combination with MUC1 and MUC16 (CA125). Mod Pathol. 2006;19:1386–1394. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lakshmanan I, Ponnusamy MP, Das S, et al. MUC16 induced rapid G2/M transition via interactions with JAK2 for increased proliferation and anti-apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2012;31:805–817. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]