Abstract

Approximately 25% of youths experience a natural disaster and many experience disaster-related distress, including symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression. This study contributes to the literature by examining PTSD and depressive symptoms among 2,000 adolescents (50.9% female, 70.5% White) assessed after exposure to tornadoes in 2011. The authors hypothesized that greater tornado exposure, female sex, and younger age would be associated with distress, and that social support would interact with these associations. Analyses showed that PTSD symptoms were predicted by lower levels of social support (β = −.28, p < .001), greater tornado exposure (β = .14, p<.001), lower household income (β = −.06, p = .013, female sex (β = −.10, p<.001), and older age (β = .07, p = .002), with a 3-way interaction between tornado exposure, sex, and social support (β = −.06, p = .017). For boys, the influence of tornado exposure on PTSD symptoms increased as social support decreased. Regardless of level of tornado exposure, low social support was related to PTSD symptoms for girls; depressive symptom results were similar. These findings are generally consistent with the literature and provide guidance for intervention development focused on strengthening social support at the individual, family, and community levels.

Nearly 25% of US adolescents have experienced a disaster (Ruggiero, Van Wynsberghe, Stevens, & Kilpatrick, 2006). Youths are at particular risk for postdisaster distress because they are less equipped to cope with disasters than adults due to less well-developed coping skills (e.g., Garnefski, Legerstee, Kraaij, van den Komer, & Teerds, 2002) and social and material resources. Youths’ distress may also be compounded by the disaster’s effects on caregivers and family (e.g., parental psychopathology, loss of stability and support; Wang et al., 2013). Research is needed to identify correlates of postdisaster adolescent mental health that may inform decisions about individual, family, and/or community-resilience interventions. In particular, research on frequently occurring but understudied types of disasters, such as tornadoes, is needed.

In 2011, 1,691 tornadoes hit the US; 758 occurred in April alone (NOAA, 2012). Beyond their immediate threat, tornadoes may result in other potentially traumatic stressors, including injury to, or loss of, loved ones, and forced relocation (Furr, Comer, Edmunds, & Kendall, 2010). Responses to natural disasters are affected by the ability to predict and prepare for them, ranging from days for hurricanes to minutes for tornadoes (Evans & Oehler-Stinnett, 2006a). Of note, tornadoes’ quick and unpredictable movement further impacts preparedness and the implementation of safety measures (Miller et al., 2012).

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms are often reported by youths exposed to heterogeneous disasters; depression is less commonly assessed but may also occur (e.g., Furr et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2013). Numerous variables across multiple domains (e.g., individual, family, community; Masten & Obradovic, 2008) have a moderate influence on postdisaster outcomes (Bonanno, Brewin, Kaniasty, & La Greca, 2010), but findings are often mixed and inconclusive, as the populations studied, the outcomes assessed and measures utilized, and the timeframe in which research is conducted varies widely. La Greca and colleagues (1996; 2010) proposed that characteristics of the child (e.g., sex, coping skills), the disaster (e.g., exposure severity) and the recovery environment (e.g., social support) influence children’s postdisaster distress.

Variables associated with postdisaster distress include degree of disaster exposure (e.g., perceived life threat; Furr et al., 2010; Pfefferbaum, Noffsinger, Wind, & Allen, 2014) and female sex (e.g., Kronenberg et al., 2010; Lonigan et al., 1994), although not all studies find sex differences (cf. Evans & Oehler-Stinnett, 2006b). Similarly, both younger (e.g., Kronenberg et al., 2010; McDermott & Palmer, 2002) and older age are associated with distress (e.g., Felton, Cole, & Martin, 2013; McDermott & Palmer, 2002) and age-related findings in tornado-exposed samples are mixed (cf. Evans & Ohler-Stinnett, 2006b; Houlihan et al., 2008). This lack of clarity in age-related findings is affected by the methodological concerns noted above and supports the need for continued research in this area. These findings underscore that sociodemographic variables may interact with other variables (e.g., youths’ social ecologies) to influence postdisaster distress. Research is needed that addresses the questions ‘for whom’ and ‘under what conditions’ do PTSD and depression develop following a disaster.

Youths’ social environments may play an important role in predicting postdisaster distress and may interact with other characteristics to convey risk or resilience. One variable of importance in this area is social support, as youths’ relationships with caregivers, family members and peers may strongly influence resilience and postdisaster outcomes (e.g., Bonanno et al., 2010; Masten & Obradovic, 2008). Social support can be particularly important in the face of a tornado, as families often gather together for safety and comfort during the storm and report utilizing high levels of social support posttornado (Miller et al., 2012).

Social support may directly affect postdisaster distress; it is linked to better post-trauma adjustment among children and adolescents and lower levels of PTSD and depression (e.g., Ellis, Nixon, & Williamson, 2009; La Greca et al., 1996; 2010). Parental distress and parenting practices are associated with poorer outcomes among hurricane-exposed youths (Kelley et al., 2010; Spell et al., 2008). Deficits in peer support among adolescents are associated with greater depression (e.g., Burton, Stice, & Seeley, 2004; Zimmerman, Ramirez-Valles, Zapert, & Maton, 2000). Further research on social support and postdisaster distress can clarify the role of this support with specific populations and disasters.

This study assessed adolescents’ social support from family and peers and its potential interaction with disaster-related environmental variables and sociodemographic characteristics on posttornado distress. Three primary hypotheses were informed by previous findings in this area. First, we hypothesized that greater exposure to the tornado would be associated with greater distress. Second, we hypothesized that girls and younger youths in the sample would report greater distress. Third, we hypothesized that social support would interact with trauma exposure and sociodemographic variables and distress, in that greater social support would help to buffer against the possible negative effects of the tornado across different levels of exposure to the tornado and socio-demographic variables.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The full methodology of the study is described in detail by Ruggiero et al. (2015). Briefly, we recruited 2,000 families with adolescents from areas affected by the tornadoes in Alabama on April 25–28 (n = 1,660) and Joplin, Missouri on May 22, 2011 (n = 340). These devastating storms resulted in the injuries to over 3,000 individuals, and deaths of over 350 residents of these areas, as well as destruction of many homes and buildings (National Weather Service [NWS], 2011a; NWS, 2011b). Recruitment procedures were previously described in detail (Adams et al., 2014; Ruggiero et al., 2015). Briefly, tornado track coordinates were used to set parameters for a targeted address-based sampling strategy, allowing for identification and recruitment of households affected by the storms, including cell-phone only households. We then used a two-stage process to identify and recruit eligible participants. First, we identified household addresses within the radii for which a landline telephone match could be made from public listings (matched sample of 107,614 households). Second, household addresses for which we were unable to identify a matched landline phone number (unmatched sample of 104,428 households; mostly cell phone-only households) were mailed a letter that explained the study, a screening questionnaire, and an invitation to participate in the study. A telephone number also was requested. A survey research firm (Abt SRBI) then contacted households to confirm study eligibility.

Eligibility for the study included residence in the targeted address at the time of the tornado, presence of an adolescent in the household, and reliable Internet access at home because data were collected as part of a randomized controlled trial evaluating the utility of a web-based, disaster mental health intervention. This criterion had minimal impact on recruitment or representativeness (Adams et al., 2014). In homes with more than one eligible caregiver or adolescent, the most recent birthday method was used to randomly select participants. Only English-speaking families, which included 95% of households in the affected regions, were eligible to participate. Following provision of informed consent, adolescent-caregiver dyads completed a structured computer-assisted telephone interview at baseline between September 2011 and June 2012, on average 8.8 months after tornado exposure (SD = 2.59; range = 4.98–13.50). Interviews were conducted by highly trained, supervised employees of Abt SRBI, a firm with extensive experience conducting health research on sensitive topics. The overall cooperation rate was 61% and participating households were mailed a $15 incentive. The adjusted response rate – defined as number of completers divided by adjusted eligible households – was 30% for the matched telephone sample and 46% for the unmatched sample from the pool of households that returned mailed screeners. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Medical University of South Carolina.

Measures

The sex and age of adolescents and caregivers was assessed. Adolescents were asked whether they considered themselves White, Black, or some other race. Youths’ caregivers were also asked to report their household income, which was coded as: (a) under $20,000, (b) $20,000–$40,000, (c) $40,000–$60,000, (d) $60,000–$80,000, (e) over $80,000.

Caregivers were asked several questions about the family’s experiences during and after the tornado, including if they (a) were present during it; (b) sustained physical injuries; (c) were concerned about the safety or whereabouts of loved ones; sustained damage to their (d) homes, (e) vehicles, (f) furniture, (g) personal items, (h) crops/landscaping or (i) pets; were without basic services for more than one week, including (j) water, (k) electricity, (l) clean clothing, (m) food, (n) shelter, (o) transportation, or (p) spending money; and (q) were displaced or forced to relocate for more than one week. Responses to these questions formed an Exposure to Tornado scale, which represented a count of how many items were endorsed (range: 0–17, Kuder-Richardson-20 = .79).

Adolescents completed a modified version of the Social Support for Adolescents Scale (SSAS; Seidman et al., 1995) to assess the extent to which adolescents could turn to their mothers, fathers, siblings, close friends, and peers for (a) emotional social support (“talking about a personal problem”); (b) instrumental social support (“money and other things”); and (c) recreational social support (“have fun with”). Responses were on a 3-point rating scale from 1 = not at all to 3 = a great deal for the 6 months prior to the tornado. Subscales were summed to create an overall measure of social support, with higher scores indicating greater perceived support. The measure had adequate internal consistency, α = .69.

Adolescent PTSD was assessed using the PTSD module from the National Survey of Adolescents (NSA) also used in other large-scale epidemiologic surveys conducted by this research team (Kilpatrick et al., 2003; Resnick et al., 1993). This structured interview assessed the presence of each of the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 2000) symptom criteria for PTSD. Participants reported on presence/absence of symptoms “since the tornado” (yes/no format); participants may have reported on symptoms related to the tornado or another traumatic event that occurred since that time (i.e., mean of 8 months post-tornado). Research supports the interview’s reliability and concurrent validity (e.g., Kilpatrick et al., 2003; Resnick et al., 1993). Internal consistency was acceptable (Cronbach’s α =.87.)

Adolescent major depressive episode (MDE) was assessed using the NSA Depression module. This structured interview assessed for the presence of each of the DSM-IV symptom criteria for an MDE since the tornado. Psychometric data support internal consistency (Kilpatrick et al., 2003) and convergent validity (Adams, Boscarino, & Galea, 2006). Internal consistency in the current sample was also adequate; α =.79.

Data Analysis

Data were weighted to obtain population-based estimates for analyses based on 2010 U.S. Census data for the target population. The base sampling weight is the reciprocal of the probability of selection, adjusted to account for eligible nonrespondents. Adolescent weights were obtained by multiplying household weight by the number of teens eligible for the study in each household. Descriptive statistics are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics for tornado exposed adolescents Exposed to 2011 Tornados

| Characteristic | Child

|

Caregiver

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Male | 1,012 | 50.6 | 1,475 | 73.8 |

| White | 1,413 | 70.5 | 1,413 | 71.2 |

| Black | 477 | 25.6 | 477 | 25.1 |

| Other | 110 | 3.9 | 95 | 4.8 |

| Annual income | ||||

| <$20,000 | 401 | 22.1 | ||

| $20,000–$39,999 | 347 | 19.1 | ||

| $40,000–$59,999 | 317 | 17.5 | ||

| $60,000–$79,999 | 237 | 13.1 | ||

| $80,000+ | 511 | 28.2 | ||

| In previous natural disaster | 543 | 27.3 | ||

| Married | 1,401 | 70.2 | ||

Note. N=2,000.

Missing data patterns were examined among all key study variables. Little’s (1988) missing completely at random (MCAR) test was used; results suggested that the data were missing completely at random, χ2(95) = 90.04, p = .634. We examined bivariate correlations between all variables (see Table 2) and computed independent samples t-tests to assess sex differences among experienced tornado severity, PTSD and depressive symptoms. In order to examine the effect of social support, amount of tornado severity experienced, demographic factors (gender, age, income level), on postdisaster psychological symptoms, we conducted two hierarchical linear regression analyses using PTSD and depressive symptoms as our outcome variables. The first hierarchical linear model examined predictors of posttornado PTSD symptoms, including sociodemographic variables (i.e., sex, age, income) experienced tornado severity and social support, as well as their interactions. In the first step, only main effects were considered. Exploratory analyses were conducted to determine if race was associated with mental health outcomes after controlling for other relevant variables. Given that race was not a significant predictor of distress in the presence of other socio-demographic variables, these analyses were omitted. In the second step, all two-way interactions between social support, experienced tornado severity, and either sex or age were added (retaining all lower-order terms). Finally, two three-way interactions between experienced tornado severity, social support, and either sex or age were included. Using a hierarchical approach allowed for the examination of the effects of lower-order terms as well as the interactions between predictors. We also centered all continuous variables in order to aid in the interpretability of our effects. Significant interactions were probed by estimating conditional effects of our variables, plus and minus one SD from the mean.

Table 2.

Non-missing n, Means, standard deviations, and Correlations for study variables

| Variable | N | M or n | SD or % | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sex (male) | 2,000 | 1,012 | 50.6 | -- | |||||

| 2. Age | 1,997 | 14.56 | 1.75 | −.05* | -- | ||||

| 3. Income | 1,813 | -- | -- | .08** | .05* | -- | |||

| 4. Social support | 1,974 | 7.09 | 1.64 | −.02 | .00 | .14** | -- | ||

| 5. Exposure severity | 1,968 | 5.04 | 3.15 | −.06* | .00 | −.35** | −.07** | -- | |

| 6. PTSD symptoms | 1,999 | 2.47 | 3.36 | −.11** | .08** | −.16** | −.30** | .19** | -- |

| 7. Depression symptoms | 1,998 | 1.35 | 1.94 | −.11** | .10** | −.16** | −.31** | .16** | .77** |

Note. n and % values for each income category are presented in Table 1. PTSD = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

p< .05.

p< .01.

Results

Means and standard deviations for all of the study variables appear in Table 2. Clinical levels of adolescents’ PTSD and depressive symptoms were also examined. PTSD symptoms ranged from 0 to 17, with 7.3% meeting diagnostic criteria for probable PTSD since the tornado. Depressive symptoms ranged from 0 to 9, with 8.5% meeting diagnostic criteria for a probable major depressive episode since the tornado (see also Adams et al., in press).

Bivariate correlations were computed for all variables (see Table 2). Social support was negatively related to PTSD and depressive symptoms. Experienced tornado severity was positively related to PTSD and depressive symptoms, as well as age. Both PTSD and depressive symptoms were correlated with age and each other, indicating that older adolescents were more likely to endorse symptoms of both disorders.

There also were effects of household income on tornado exposure F(4, 1784) = 60.36, p < .001, PTSD symptoms F(4, 1812) = 11.45, p < .001, and depressive symptoms F(4, 1811) = 12.68, p<.001. Post-hoc Tukey comparisons between groups indicated that participants with household incomes below $20,000 (M = 6.71, 95% CI [6.36, 7.06]) reported greater experienced tornado severity than all other income groups. Youth with household incomes below $20,000 also experienced a greater number of PTSD symptoms (M = 3.16, 95% CI [2.79, 3.54]) and depressive symptoms (M = 1.77, 95% CI [1.56,1.98]) than youth in household reporting more than $40,000 annual income.

Adolescent girls reported greater experienced tornado severity (M = 3.18, SD = 0.10) than boys (M = 3.10, SD = 0.10), t(1966) = 2.59, p = .010; however, this effect was small, r = .06. Adolescent girls reported experiencing a greater number of PTSD symptoms (M = 2.83, SD = 3.62) than boys (M = 2.12, SD = 3.05), t(1997) = 4.69, p < .001; this effect was small, r = .11. Adolescent girls also reported a greater number of posttornado depressive symptoms (M = 1.56, SD = 2.13) than boys (M = 1.13, SD = 1.70), t(1996) = 4.50, p < .001; this effect also was small, r = .11.

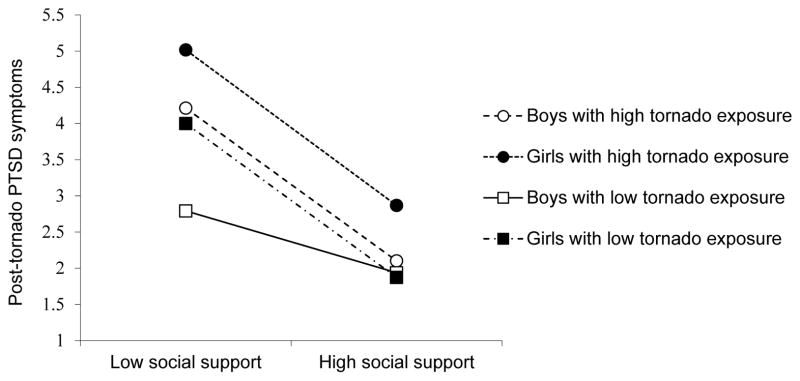

Next, we ran a series of hierarchical linear regression models examining predictors of PTSD symptoms, described above. The initial model was significant (R2 = .14, F(5, 1751) = 55.70, p < .001) and findings suggest that lower levels of social support (β = −.57, p < .001), greater experienced tornado severity (β =.15, p < .001), lower household income (β = −.13, p = .013), female sex (β = −.67, p < .001), and older age (β = .13, p = .002) were associated with greater PTSD symptoms. The change in the proportion of variance in PTSD symptoms explained by the second step was not significant (R2 =.14, ΔR2 =.01, ΔF(5, 1746) = 1.99, p = .077). Only the social support by experienced tornado severity interaction term was significant (β = −0.03, p = .019). In the final step (R2 =.15, ΔR2 =.003, ΔF(2, 1744) = 2.85, p = .058), only the interaction between sex, experienced tornado severity and social support was significant and emerged for boys, but not for girls (see Table 3 for the final step). This interaction suggests that, for boys at low (−1 SD) and average levels of social support, experienced tornado severity affected PTSD symptoms; this effect became nonsignificant as social support increased. For girls, lower levels of social support were associated with greater PTSD symptoms regardless of tornado severity (see Figure 1).

Table 3.

Final Step of Hierarchical linear model of Associations with posttornado PTSD symptoms.

| Variable | B | SE B | β | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 2.83 | 0.18 | -- | 15.73** |

| Sex (male=1) | −.68 | 0.15 | −.10 | −4.53** |

| Age | 0.12 | 0.04 | .07 | 2.90** |

| Income | −0.12 | 0.05 | −.06 | −2.34* |

| Social support | −0.55 | 0.05 | −.27 | −11.97** |

| ETS | 0.15 | 0.03 | .14 | 5.83** |

| Social support × ETS | −0.03 | 0.01 | −.05 | −2.33* |

| Sex × Social support | 0.21 | 0.09 | .05 | 2.25* |

| Sex × ETS | −0.03 | 0.05 | −.02 | −0.72 |

| Age × Social support | −0.01 | 0.03 | −.01 | −0.44 |

| Age × ETS | 0.00 | 0.01 | .00 | 0.15 |

| Sex × Social support × ETS | −0.06 | 0.03 | −.06 | −2.39* |

| Age × Social support × ETS | 0.00 | 0.01 | −.01 | −0.59 |

Note. N=1,756. R =.15, ΔR =.003, p=.058. ETS = Experienced Tornado Severity.

p< .05.

p< .01.

Figure 1.

N = 1,745. Plot of three-way interaction of social support, experienced tornado severity, and sex

A similar hierarchical linear regression was conducted with respect to symptoms of depression. The first step of the model was significant (R2 = .14, F(5, 1750) = 57.64, p < .001), with less social support (β = −0.35, p < .001), lower household income (β = −0.10, p = .002), greater experienced tornado severity (β = 0.07, p < .001), female sex (β = −0.38, p < .001) and older age (β = 0.10, p <.001), associated with greater depressive symptoms. The change in the proportion of variance in depression symptoms explained by the second step was significant (R2 = .15, ΔR2 = .01, ΔF(5,1745) = 2.31, p = .042), and only the social support by sex interaction was significant (β = 0.12, p = .024). The final step in the model also represented a significant increase in the explained variance in depressive symptoms (R2 = .15, ΔR2 = .003, ΔF(2, 1743) = 3.45, p = .032) and the three-way interaction between sex, social support and experienced tornado severity was significant (see Table 4 for the final model). The pattern of findings was similar to results depicted in Figure 1, suggesting that the conditional effect of the interaction between social support and experienced tornado severity was significant for boys only. We subsequently re-ran all analyses controlling for the state in which data was collected. These analyses did not substantially or meaningfully change any results and were therefore omitted.

Table 4.

Final Step of Hierarchical linear model of Associations with posttornado Depression symptoms.

| Variable | B | SE B | β | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.61 | 0.10 | -- | 15.53** |

| Sex (male=1) | −0.38 | 0.09 | −.10 | −4.46** |

| Age | 0.10 | 0.03 | .09 | 3.93** |

| Income | −0.09 | 0.03 | −.07 | −2.95** |

| Social Support | −0.33 | 0.03 | −.29 | −12.60** |

| ETS | 0.07 | 0.02 | .11 | 4.51** |

| Social support × ETS | −0.01 | 0.01 | −.04 | −1.81 |

| Sex × Social support | 0.14 | 0.05 | .06 | 2.58* |

| Sex × ETS | −0.03 | 0.03 | −.03 | −1.12 |

| Age × Social support | −0.02 | 0.02 | −.03 | −1.20 |

| Age × ETS | 0.00 | 0.01 | .01 | 0.21 |

| Sex × Social support × ETS | −0.04 | 0.02 | −.06 | −2.63* |

| Age × Social support × ETS | 0.00 | 0.00 | −.01 | −0.58 |

Note. N=1,755, R2=.15, ΔR2=.003, p=.032. ETS = Experienced Tornado Severity.

p< .05.

p< .01.

Discussion

This study advanced the field by assessing the role of multiple variables – assessed across multiple levels of youths’ experience and ecology – on posttornado PTSD and depression symptoms in a large sample of adolescents. General findings regarding rates of distress in this sample were consistent with those from postdisaster community samples (e.g., Goenjian et al., 2011), and discrepancies between these findings and previous research on tornado-exposed adolescents (e.g., Adams et al., in press) are likely due to differences in outcome variables, given the focus on symptoms – vs. diagnoses – of PTSD and depression in this study. Thus, these results address a different research question by looking at those factors that influence the full range of distress symptoms among youths post-disaster.

The study hypotheses were generally supported. The results suggest that girls were more likely to report symptoms of PTSD and depression, but that older rather than younger adolescents reported greater posttornado pathology. This finding is consistent with recent research, in which the authors speculated that older youths may engage in maladaptive cognitive coping (e.g., rumination; Felton et al., 2013), consistent with research on adolescent responses to stressors (Garnefski, Kraaij, & Spinhoven, 2001). Additionally, lower income was also associated with distress and further explication of related variables (e.g., availability of resources, additional income-associated life stressors) can help to clarify the role of this variable in post-disaster distress.

The findings also suggest that qualities of one’s disaster exposure and the postdisaster environment are important for identifying youths at the greatest risk for psychopathology. Consistent with previous research (e.g., La Greca et al., 2010), these results indicate that increased tornado exposure and resultant losses were associated with greater psychopathology. Higher levels of posttornado social support appeared to buffer against symptoms of PTSD and depression. Few studies have examined the role of both family and peer-related supported on postdisaster functioning (cf. La Greca et al., 2010) and available findings highlight the important role that both groups play in youths’ recovery. Strong social support networks may suggest that youths have access to both psychological and material resources to assist in recovery, and explication of the most valuable types of postdisaster support is needed.

Our results extend previous findings by considering interactive effects; importantly, these relations differed by sex. For boys, social support was an important buffer against the onset of distress among those who had the greatest experienced tornado severity. Thus, strong predisaster social support networks may be particularly important in protecting against distress for boys exposed to extreme traumatic events. For girls, social support did not influence this relation. Instead, social support predicted PTSD and depression at all levels of tornado severity, suggesting that it is a crucial factor in girls’ post-trauma environments. This finding is consistent with research on community and non-disaster-exposed individuals that shows social support to be a critical buffer against psychopathology for women and girls (e.g., Lewinsohn, Hoberman, & Rosenbaum, 1988; Slavin & Rainer, 1990).

These results also provide a critical extension to current stress-buffering models, which suggest that social support mitigates the relation between stressful events and the onset of distress. Support for the stress-buffering model is mixed, with some studies of adolescents supporting an interactive relation between stress and social support (e.g., DuBois, Felner, Brand, Adan & Evans, 1992) and others not (cf., Burton et al., 2004). Importantly, many of these studies did not consider sex, and most used community samples of adolescents with low levels of reported stressors. The findings presented here extend this model to a disaster-exposed population, which naturally includes youths with exposure to a wider range of stressors (e.g., sustained injury, forced relocation). These results suggest that the buffering effect of social support may only be evident at greater levels of stressor severity for boys while, consistent with previous research (e.g., Burton et al., 2004), social support exerts a pronounced effect on pathology at all levels of stressor exposure for girls.

Despite the strengths of the current study, several limitations suggest avenues for future research. First, these relations were examined cross-sectionally, and youths’ predisaster functioning and social support were not assessed. Second, we were unable to confirm that PTSD symptoms endorsed “since the tornado” were specifically related to the tornado rather than other traumatic events, nor were we able to assess the impact of multiple tornado exposures on mental health outcomes due to the composition of the interview. This approach is typical in research of this nature where the majority of items on most well-validated PTSD instruments do not tie symptoms to a specific event (e.g., exaggerated startle, concentration difficulties, irritability). Although we could have taken steps in the interview to strengthen these connections (e.g., adding follow up questions such as “what were the nightmares about?”, questions about situations and thoughts that participants reported avoiding), it is important to note that such steps were cost prohibitive given our large sample size and limited budget. These limitations in measurement temper the conclusions that can be drawn about specific tornado-related distress. Further, the loss variable was a summative count of the presence or absence of many types of loss that did not address relative differences in importance or impact of loss types for each participant; thus, it was a relatively general measure of loss. Third, the measures used were self-report and conducted within 4–14 months posttornado. Of note, most research is self-report and conducted immediately after, or years following, the disaster; the timeframe used in this study may better assess persistent distress after the tornado. Fourth, some implicated variables (e.g., coping styles), were not assessed and including them with parent and peer perspectives on children’s coping, social support and functioning is important, as such assessment could allow for comparisons between perceived and actual coping and support.

Resilience in the face of trauma is relatively common (e.g., Bonnano & Mancini, 2008); however, for an important minority of adolescents, trauma exposure can lead to severe and impairing mental health problems. Given the limited resources available following natural disasters, our findings provide guidance with respect to possible audiences for, and foci of, post-disaster interventions. These findings highlight the role of social support, and support the recommendations for community-level interventions to build resilience post-disaster (e.g., Chandra et al., 2010). This focus is particularly suited to disaster response, given that disasters may affect an entire community.

Groups that are at heightened risk for postdisaster distress should be assessed and provided with needed support and services, including youths with greater disaster-related exposure and loss, lower income, and those who may have less available social support available (e.g., children with few friends). Given the recognition of maintaining and/or restoring social support post-disaster (e.g., Masten & Obradovic, 2008), attention should be paid to bolstering family and peer support for these youths and increasing positive interpersonal interactions. Additionally, targeting youths, families and communities with histories of disaster and other trauma exposure is important, given that this history is associated with greater postdisaster distress (e.g., Galea, Nandi, & Vlahov, 2005). Instruction in effective and adaptive coping skills and the provision of hope is also important for bolstering resiliency (Osofsky & Osofsky, 2013). Such interventions can be conducted with youths and their peers and families at the community-level to have a broader impact. The development of such targeted interventions that focus on both risk and protective factors is vital to creating effective postdisaster treatment efforts and improving outcomes for youths following tornadoes and other disasters.

Acknowledgments

The National Institute of Mental Health (Grant R01-MH081056 to KJR) supported this study as well as the team of collaborators (T32-MH018869 sponsoring LAP and ZWA). We thank the many families affected by the spring 2011 tornado outbreak for participating in this study.

References

- Adams RE, Boscarino JA, Galea S. Alcohol use, mental health status and psychological well-being 2 years after the World Trade Center attacks in New York City. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2006;32:203–224. doi: 10.1080/00952990500479522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams ZW, Sumner JA, Danielson CK, McCauley JL, Resnick HS, Ruggiero KJ. Prevalence and predictors of PTSD and depression among adolescent victims of the Spring 2011 tornado outbreak. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2014;55:1047–1055. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnano GA, Brewin CR, Kaniasty K, La Greca AM. Weighing the costs of disaster: Consequences, risks, and resilience in individuals, families, and communities. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2010;11:1–49. doi: 10.1177/1529100610387086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnano GA, Mancini AD. The human capacity to thrive in the face of potential trauma. Pediatrics. 2008;121:369–375. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton E, Stice E, Seeley JR. A prospective test of the stress-buffering model of depression in adolescent girls: No support once again. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:689–697. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.72.4.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A, Acosta J, Stern S, Uscher-Pines L, Williams MV, Yeung D, Meredith LS. Building community resilience to disasters: A way forward to enhance national health security. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2010. DHHS Publication No. TR-915. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois DL, Felner RD, Brand S, Adan AM, Evans EG. A prospective study of life stress, social support, and adaptation in early adolescence. Child Development. 1992;63:542–557. doi: 10.2307/1131345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis AA, Nixon RDV, Williamson P. The effects of social support and negative appraisals on acute stress symptoms and depression in children and adolescents. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;48:347–361. doi: 10.1348/014466508x401894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans LG, Oehler-Stinnett J. Children and natural disasters: A primer for school psychologists. School Psychology International. 2006a;27:33–55. doi: 10.1177/0143034306062814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evans LG, Oehler-Stinnett J. Structure and prevalence of PTSD symptomatology in children who have experienced a severe tornado. Psychology in the Schools. 2006b;43:283–295. doi: 10.1002/pits.20150. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felton JW, Cole DA, Martin NC. Effects of rumination on child and adolescent depressive reactions to a natural disaster: The 2010 Nashville flood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:64–73. doi: 10.1037/a0029303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furr JM, Comer JS, Edmunds JM, Kendall PC. Disasters and youth: A meta-analytic examination of posttraumatic stress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:765–780. doi: 10.1037/a0021482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Nandi A, Vlahov D. The epidemiology of post-traumatic stress disorder after disasters. Epidemiological Review. 2005;27:78–91. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxi003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Spinhoven P. Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30:1311–1327. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00113-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garnefski N, Legerstee J, Kraaij V, van den Kommer T, Teerds J. Cognitive coping strategies and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A comparison between adolescents and adults. Journal of Adolescence. 2002;25:603–611. doi: 10.1006/jado.2002.0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goenjian AK, Roussos A, Steinberg AM, Sotiropoulou C, Walling D, Kakaki M, Karagianni S. Longitudinal study of PTSD, depression, and quality of life among adolescents after the Parnitha earthquake. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;133:509–515. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houlihan D, Ries BJ, Polusny MA, Hanson CN. Predictors of behavior and levels of life satisfaction of children and adolescents after a major tornado. Journal of Psychological Trauma. 2008;7:21–36. doi: 10.1080/19322880802125902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RT, Frary R, Cunningham P, Weddle JD, Kaiser L. The psychological effects of Hurricane Andrew on ethnic minority and Caucasian children and adolescents: A case study. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2001;7:103–108. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ML, Self-Brown S, Le B, Bosson JV, Hernandez BC, Gordon AT. Predicting posttraumatic stress symptoms in children following Hurricane Katrina: A prospective analysis of the effect of parental distress and parenting practices. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2010;23:582–590. doi: 10.1002/jts.20573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno RE, Saundes BE, Resnick HS, Best CL. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: Results from the National Survey of Adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:692–700. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg ME, Hansel TC, Brennan AM, Osofsky HJ, Osofsky JD, Lawrason B. Children of Katrina: Lessons learned about postdisaster symptoms and recovery patterns. Child Development. 2010;81:1241–1259. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Lai B, Jacard J. Hurricane-related exposure experiences and stressors, other life events, and social support: Concurrent and prospective impact on children’s persistent posttraumatic stress symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:794–805. doi: 10.1037/a0020775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Vernberg EM, Prinstein MJ. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress in children after Hurricane Andrew: A prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:712–723. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.64.4.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Hoberman HM, Rosenbaum M. A prospective study of risk factors for unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:251–264. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.97.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of American Statistical Association. 1988;83:1198–1202. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lonigan CJ, Shannon MP, Taylor CM, Finch AJ, Sallee FR. Children exposed to disaster: II. Risk factors for the development of post-traumatic symptomatology. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1994;33:94–105. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199401000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Obradovic JD. Disaster preparation and recovery: Lessons from research on resilience in human development. Ecology and Society. 2008;13:9. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott BM, Palmer LJ. Postdisaster emotional distress, depression and event-related variables: Findings across child and adolescent developmental stages. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;36:754–761. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller PA, Roberts NA, Zamora AD, Weber DJ, Burleson MH, Tinsley BJ. Families coping with natural disasters: Lessons from wildfires and tornadoes. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2012;9:314–336. [Google Scholar]

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) Tornadoes - annual 2011. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/sotc/tornadoes/2011/13.

- National Weather Service (NWS) Weather Forecast Office. April severe weather events set new tornado records for Alabama. 2011a Retrieved from: http://www.srh.noaa.gov/bmx/?n=climo_2011torstats.

- NWS Weather Forecast Office. Joplin tornado event summary. 2011b Retrieved from: http://www.crh.noaa.gov/sgf/?n=event_2011may22_summary.

- Osofsky JD, Osofsky HJ. Lessons learned about the impact of disasters on children and families and post-disaster recovery. In: Culp AM, editor. Child and family advocacy: Bridging the gaps between research, practice, and policy. New York: Springer; 2013. pp. 91–105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum B, Noffsinger MA, Wind LH, Allen JR. Children’s coping in the context of disasters and terrorism. Journal of Loss & Trauma: International Perspectives on Stress & Coping. 2014;19:78–97. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2013.791797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Dansky BS, Saunders BE, Best CL. Prevalence of civilian trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in a representative national sample of women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:984–991. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.61.6.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero KJ, Davidson TM, McCauley J, Gros KS, Welsh K, Price M, Resnick HS, Amstadter AB. Bounce Back Now! Protocol of a population-based randomized controlled trial to examine the efficacy of a web-based intervention with disaster-affected families. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2015;40:138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruggiero KJ, Van Wynsberghe A, Stevens T, Kilpatrick DG. Traumatic stressors in urban settings: Consequences and implications. In: Freudenberg N, Vlahov D, Galea S, editors. Urban health: Cities and the health of the public. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman E, Allen R, Aber JL, Mitchell C, Feinman J, Yoshikawa H, Comtois KA, Roper GC. Development and validation of adolescent-perceived microsystem scales: Social support, daily hassles, and involvement. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23:355–388. doi: 10.1007/BF02506949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavin LA, Rainer KL. Gender differences in emotional support and depressive symptoms among adolescents: A prospective analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1990;18:407–421. doi: 10.1007/bf00938115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spell AW, Kelley ML, Wang J, Self-Brown S, Davidson KL, Pellegrin A, Baumeister A. The moderating effects of maternal psychpathology on children’s adjustment post-Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:553–563. doi: 10.1080/15374410802148210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Chan CLW, Ho RTH. Prevalence and trajectory of psychopathology among child and adolescent survivors of disasters: A systematic review of epidemiological studies across 1987–2011. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2013;48:1697–1720. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0731-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman MA, Ramirez-Valles J, Zapert KM, Maton KI. A longitudinal study of stress-buffering effects for urban African-American male adolescent problem behaviors and mental health. Journal of Community Psychology. 2000;28:17–33. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6629(200001)28:1<17::aid-jcop4>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [Google Scholar]