Abstract

Emotion dysregulation in borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with loss of cognitive control in the face of intense negative emotion. Negative emotional context may interfere with cognitive processing through the dysmodulation of brain regions involved in regulation of emotion, impulse control, executive function and memory. Structural and metabolic brain abnormalities have been reported in these regions in BPD. Using novel fMRI protocols, we investigated the neural basis of negative affective interference with cognitive processing targeting these regions. Attention-driven Go No-Go and X-CPT (continuous performance test) protocols, using positive, negative and neutral Ekman faces, targeted the orbital frontal cortex (OFC) and the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), respectively. A stimulus-driven Episodic Memory task, using images from the International Affective Pictures System, targeted the hippocampus (HIP). Participants comprised 23 women with BPD, who were compared with 15 healthy controls. When Negative>Positive faces were compared in the Go No-Go task, BPD subjects had hyper-activation relative to controls in areas reflecting task-relevant processing: the superior parietal/precuneus and thebasal ganglia. Decreased activation was also noted in the OFC, and increased activation in the amygdala (AMY). In the X-CPT, BPD subjects again showed hyper-activation in task-relevant areas: the superior parietal/precuneus and the ACC. In the stimulus-driven Episodic Memory task, BPD subjects had decreased activation relative to controls in the HIP, ACC, superior parietal/precuneus, and dorsal prefrontal cortex (dPFC) (for encoding), and the ACC, dPFC, and HIP for retrieval of Negative>Positive pictures, reflecting impairment of task-relevant functions. Negative affective interference with cognitive processing in BPD differs from that in healthy controls and is associated with functional abnormalities in brain networks reported to have structural or metabolic abnormalities. Task demands exert a differential effect on the cognitive response to negative emotion in BPD compared with control subjects.

Keywords: Functional Imaging, Emotion dysregulation, Cognitive processing, Negative emotion

1. Introduction

Emotion dysregulation is a core characteristic of patients with borderline personality disorder (BPD), a temperamental trait predisposing to disturbances of mood, cognition, and behavior (Linehan, 1993). In experimental studies, subjects with BPD experience emotions more strongly than healthy controls, especially in response to negative affect, and are slower to return to baseline once aroused (Levine et al., 1997; Jacob et al., 2008). Emotion dysregulation at times of severe stress reflects both the intensity of affective arousal and a failure of cognitive control. The two are physiologically related. Emotion modulates cognition just as cognition modulates emotion (Blair, 2004). Failure of cognitive control increases the likelihood of impulsive, aggressive, and self-injurious behaviors as a response to negative emotion in patients with BPD.

1.1. Emotion regulation in healthy subjects: the “top-down/ bottom-up” model

There is widespread consensus that emotion regulation in normal subjects involves a tonic balance between “bottom-up” limbic system arousal, and “top-down” executive control mediated through prefrontal cortical networks (Davidson et al., 2000; Gross and Thompson, 2006; Ochsner and Gross, 2006; Phillips et al., 2008; Niedtfeld and Schmahl, 2009). Limbic system involvement includes the amygdala (AMY), basal ganglia and ventral striatum, insula, hippocampus (HIP) and associated fusiform, parahippocampal and lingual gyrii. The prefrontal cortex network (PFC) includes the orbital frontal cortex (OFC), anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), dorsolateral PFC (DLPFC), and dorsomedial and ventrolateral PFC. According to this model, emotion dysregulation, especially in response to negative emotion, results from affective interference with information processing in the prefrontal cortex network in the face of limbic system hyperarousal. The resulting affective instability is well described in the clinical literature, especially in patients with BPD (Linehan, 1993; Koenigsberg et al., 2002); however, the effects of emotional stimuli on cognitive processing during task performance are poorly understood in BPD.

1.2. Fronto-limbic abnormalities in BPD

In subjects with BPD and other impulsive personality disorders (PDs), clinical symptoms such as affective instability and impulsive-aggression have been associated with structural and metabolic abnormalities in fronto-limbic networks involved in the regulation of emotion, impulse and behavior. Structural abnormalities in BPD include diminished gray matter volumes in the OFC and adjacent areas of the PFC, in the ACC, HIP and AMY (Driessen et al., 2000; Rüsch et al., 2003; Schmahl et al., 2003b; Tebartz van Elst et al., 2003; Brambilla et al., 2004; Hazlett et al., 2005; Irle et al., 2005; Zetzsche et al., 2007; Soloff et al., 2008; Sala et al., 2011; Ruocco et al., 2012; Soloff et al., 2012). Metabolic studies of patients at rest (positron emission tomography, PET), and following serotonergic challenge (fenfluramine-PET, mCPP-PET), report decreased metabolism and blunted serotonergic responses in related areas, including the OFC and ventral medial PFC, cingulate gyrus, and temporal cortex, with diminished normal connectivity between the OFC and AMY (Goyer et al., 1994; De La Fuente et al., 1997; Juengling et al., 2003; Soloff et al., 2003; New et al., 2007). Although strongly suggestive, the identified structural and metabolic abnormalities do not prove functional impairment. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies in BPD have addressed the issue by mapping neural responses to emotional stimuli (especially negative emotion) and the cognitive processes that regulate them.

1.3. fMRI studies of emotion regulation in BPD

Aversive pictures from the International Affective Pictures System (IAPS), and emotionally valenced Ekman faces, exert an exaggerated effect on limbic structures in BPD, including hyperarousal of the AMY and associated fusiform gyrus (involved in facial recognition) (Herpertz et al., 2001; Donegan et al., 2003; Koenigsberg et al., 2009). In response to viewing fearful Ekman faces, BPD subjects also have significantly greater deactivation in the rostral/subgenual ACC bilaterally compared with normal controls (Minzenberg et al., 2007). These studies suggest limbic hyperarousal and diminished cortical inhibition in response to negative emotional context, but they do not specifically assess affective interference with regional brain function during cognitive task performance.

An fMRI study of affective interference using an “emotional linguistic Go No-go task,” found decreased activity in BPD subjects in the medial OFC and sub-genual ACC, and increased activity in the bilateral AMY during task performance. In the “emotional linguistic Go No-go task,” subjects had to discriminate between emotionally valenced words written in italic or standard font. Negative words were chosen for their emotional valence to BPB subjects and were paired with an inhibitory command (“No-go”) (Silbersweig et al., 2007). In an “emotional Stroop task” (in which subjects were asked to name ink colors in which affectively valenced words are written), healthy subjects activated inhibitory fronto-limbic structures in response to negative words (compared with neutral words), while BPD subjects showed no differences in activation between conditions, suggesting diminished inhibitory control (Wingenfeld et al., 2009). Koenigsberg et al. (2009) used a cognitive reappraisal task in which BPD subjects were asked to psychologically distance themselves and suppress negative emotional experience while viewing aversive IAPS pictures. BPD subjects were less efficient than control subjects in activating ACC during the suppression task (Koenigsberg et al., 2009). In a similar design, Schulze et al. (2011) demonstrated diminished activation of the OFC (lt.) and increased activation of the bilateral insula in BPD subjects who were asked to down-regulate emotional responses to negative IAPS pictures through cognitive reappraisal. These studies have been interpreted as consistent with the “top-down/bottom-up” hypothesis of emotion regulation (Krause-Utz et al., 2014). During cognitive processing, however, the balance between limbic arousal and prefrontal cortical control may be modified by the processing demands of the task, as well as the effects of emotional valence. To the best of our knowledge, no prior fMRI studies of BPD subjects have used multiple tasks with different cognitive demands to assess differential effects of affective interference on cognitive functioning during task performance.

This study was designed to test the hypothesis that negative emotion will be associated with functional impairment (affective interference) in cognitive processing in regions with known structural or metabolic abnormalities in BPD (e.g., OFC, ACC, HIP), and that the response to affective interference with cognitive processing will be influenced by the processing demands of the task . To assess this hypothesis, we compared inter-condition effects associated with negative, neutral and positive valence. Specifically, we hypothesized that cortical processing during response inhibition (a function of the OFC), attention and conflict resolution (a function of the ACC), and episodic memory encoding and retrieval (a function of the HIP) would be impaired by negative emotion in BPD compared with findings in control subjects. Furthermore, we hypothesized that task demands (attention-driven vs. stimulus driven tasks) would exert differential effects on cognitive processing in BPD patients compared with control subjects during negative affective interference.

2. Methods

2.1. Inclusion criteria

The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh IRB. Female subjects (18-45 years of age) were recruited from the first author’s ongoing longitudinal study of BPD, from psychiatric outpatient clinics, and by advertisement from the surrounding community. The study was restricted to females as they comprise 75% of BPD patients in clinical settings (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). This design also avoids any confounds due to gender. All subjects gave written informed consent. Subjects were screened for BPD with the International Personality Disorders Examination (IPDE), using a lifetime time frame (Loranger, 1999). Those meeting criteria for probable or definite lifetime BPD on the IPDE were then assessed for current BPD with the Diagnostic Interview for Borderline Patients-Revised (DIB-R), which has a 2-year time frame for current symptoms (Zanarini et al., 1989; Loranger, 1999). Inclusion required a score of 8 or greater (i.e., definite BPD). Co-morbidity on Axis I was determined by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (First et al., 2005). Control subjects had no lifetime Axis I or II diagnoses, were physically healthy, and free of psychoactive medications and substances of abuse. Immediately preceding the scan, all subjects had negative urine toxicology for drugs of abuse and female subjects had negative pregnancy tests. BPD subjects on psychoactive medication were permitted to remain on their medication.

2.2. Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria included the following: (1) a lifetime (past or current) Axis I diagnosis of schizophrenia, delusional (paranoid) disorder, schizoaffective disorder, any bipolar disorder (I, II, mixed, manic or depressed) or psychotic depression. (2) A current DSM-IV diagnosis of substance dependence or any current drug- or alcohol-related CNS deficits. (A DSM-IV diagnosis of substance abuse was permitted so long as the subject had been abstinent for 1 week, showed no signs of withdrawal, and had a clean urine toxicology drug screen (MedTox) at the time of the scan.) (3) Clinical evidence of CNS pathology of any etiology, including acquired or developmental deficits or seizure disorder. (4) Physical disorders or treatments with known psychiatric consequence (e.g., hypothyroidism, steroid medications). (5) Borderline mental retardation (IQ <70 on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale). (6) Standard exclusion criteria for MRI scans include the following: ferro-magnetic implants such as cardiac pacers, cochlear implants, aneurysm clips, history of metal in eyes or other ferromagnetic body artifacts; inability to fit in the scanner due to obesity, claustrophobia or inability to tolerate brief confinement in the scanner; inability to co-operate with instructions.

2.3. Imaging specifications

Anatomical images were acquired on the 3.0 Tesla Siemens Trio system in the axial plane parallel to the anterior-commissure/posterior commissure (AC-PC) line using a three-dimensional MPRAGE sequence as follows: echo time (TE)/inversion time (TI)/repetition time (TR)=3.29 ms/900 ms/2200 ms, flip angle=9, isotropic 1 mm3 voxel, 192 axial slices, matrix size=256×192). fMRI data were acquired in the axial plane using a gradient echo echoplanar imaging sequence (TR=2000 ms, TE=30 ms, flip angle=70 degrees, 30 slices, slice thickness=3.1 mm, 3 mm × 3 mm in-plane, matrix size=64×64).

A comprehensive set of regional responses was investigated in the fMRI analyses. The anatomical mask included regions that are associated with emotion regulation, attention, and memory. We have previously demonstrated that all of these regions evince structural deficits in BPD (Soloff et al., 2008; Soloff et al., 2012; Soloff et al., 2014), thus providing a bridge between structural deficits in BPD and their correlates in dysfunction. The anatomical mask is depicted in Supplemental Fig. 1 and includes the AMY, HIP and parahippocampus, the parietal lobe, the OFC, the DLPFC, the cingulate gyrus and the basal ganglia.

2.4. fMRI paradigms (Fig. 1)

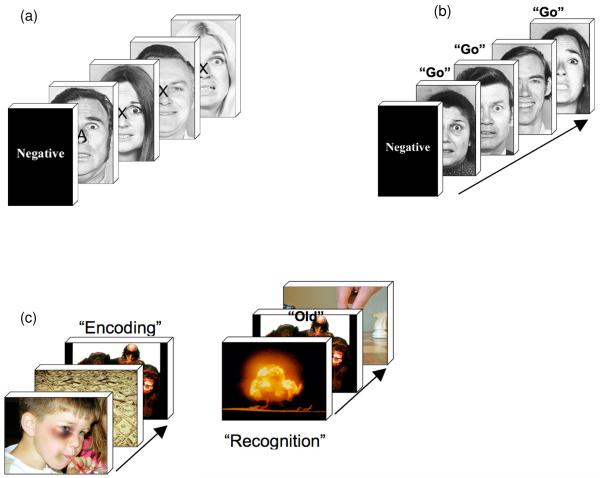

Figure 1.

a) The figure depicts the affective CPT paradigm. During a given epoch, participants were instructed to respond to targets, “X” only if they appeared on faces that depicted the target affect for the epoch. The task required selective attention gain for epoch-consistent faces. b) During the affective go-no-go task, participants responded if the affect signaled by a face was consistent with the target affect for that epoch. As with the affective CPT, the task required selective attention gain for epoch-consistent faces in order to gate the response. c) The affective episodic memory paradigm employed IAPS pictures in an alternating Encoding-Retrieval epoch structure. Unlike a) and b), participants were not asked to selectively attend to specific stimulus attributes.

Three behavioral paradigms were specifically modified for this protocol by inserting affective stimuli (Ekman Faces, IAPS pictures) into standard Go No-Go, Continuous Performance Test (X-CPT), and Episodic Memory paradigms (Ekman and Friesen, 1976; Lang and Cuthbert, 2001). During the Affective Go No-Go and X-CPT paradigms, responses were determined by the affective context of the task (i.e., negative, positive or neutral faces). Requiring subjects to focus attention on the affective context allowed us to assess differential effects of affective context on attention-driven cognitive processing in regional brain responses. During the Affective Episodic Memory task, subjects discriminated “old versus new” IAPS pictures, a stimulus-driven task that allowed us to assess the differential effects of affective context on stimulus-driven cognitive processing in regional brain responses. Deploying affectively valenced faces and pictures instead of the traditionally used stimuli allowed us to investigate the effects of affective interference on regional brain responses in regions previously characterized by structural or metabolic abnormalities in subjects with BPD (e.g., the OFC, ACC, and HIP). Subjects performed the three fMRI tasks in a single session, and in a fixed order: Go No-Go, X-CPT, Episodic Memory.

The Go No-Go test is a neuropsychological measure of response inhibition and impulsivity. It requires subjects to inhibit a prepotent response and respond based on target class that reliably engages the OFC (Mesulam, 1985; Casey et al., 1997). Ekman faces were presented briefly (500 ms) in a mixed jittered event-related design (interstimulus interval range: 500-1500 ms in 250-ms increments (Donaldson et al., 2001; Amaro and Barker, 2006). The target affective context was signaled at block onset, and subjects responded if the affect in the face was consistent with the affective context (67% targets). Four block types were used (three repetitions, 30-s block length): Negative, Neutral and Positive valence and Distorted blocks (in which target images were scrambled faces), with three fixation blocks interspersed. The length of this task was 9 min 27 s.

The X-CPT is a continuous performance task that assesses contextual attention to context-relevant targets by increasing response competition between targets. The X-CPT requires conflict resolution and inhibition of a prepotent response tendency, robustly activating the ACC (Carter et al., 1998; Botvinick et al., 2001; Tana et al., 2010). Contextual responses were dependent on the valence of Ekman faces on which potential target letters (e.g., “X”) and distracters (e.g., “A”) were rendered. In a mixed block jittered design, affective context signaled at the beginning of each block determined the response to potential targets (e.g., during “negative” blocks, “X” became a target only if rendered on a face with negative valence). Stimuli were presented for 1000 ms with a jittered interstimulus interval (250-750 ms, 250-ms increments). Two blocks (54 s/block) of positive, negative and neutral valence were used. In addition, three rest blocks (30 s) were used. The length of this task was 10 min 8 s.

The Episodic Memory task assesses encoding and retrieval of newly acquired episodic memories compared with previously known memories, reliably engaging the HIP (Squire and Zola-Morgan, 1991; Tulving et al., 1994; Eldridge et al., 2000). IAPS pictures were presented in a mixed block-event related design with alternating encoding and recognition epochs. During encoding, six pictures were presented (3500 ms with a randomly jittered interstimulus interval: 500-1500 ms in 250-ms increments) (Josephs and Henson, 1999). Following a retention interval of 8 s, pictures were presented during a recognition block and subjects judged if the picture had been presented previously in the encoding block or had not been previously presented (“old” vs. “new” pictures). Nine encoding-recognition pairs of blocks (27 s each) of encoding and retrieval were presented (5 s between pairs). Eighteen unique images were used for each of the conditions (negative, neutral and positive). The length of this task was 11 min 50 s.

The different block lengths were motivated by different experimental demands induced by each of the paradigms. The Go No-Go assessed impulsivity, requiring a response set to be established (which must be infrequently inhibited). The X-CPT is a contextual performance task in which subjects are sensitive to the context-relevant content of each stimulus. Similarly, in the Episodic Memory task we were interested in responses to each item during encoding or retrieval. The block orders were as follows: a) Go No-Go ( Rest, Neg, Neu, Pos, Dist, Neg, Pos, Rest, Dist, Neu, Pos, Neg, Neu, Dist, Rest); b) X-CPT ( Rest, Pos, Dist, Neg, Neu, Rest, Neu, Neg, Dist, Pos, Rest). The Episodic Memory experiment was an event-related design.

2.5. Image and fMRI data analyses

Data were processed with Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM8) using standardized methods. Serial correlations were corrected using an auto-regression (AR(1)) filter, with an expanded high-pass filter (256 s) applied to remove low frequency fluctuations. Realignment was performed to correct for head motion artifact. Normalization parameters, achieved after normalizing each subject’s high-resolution anatomical image to the template image, were applied to each acquired echoplanar image. The resultant normalized images were resliced (8 mm3 voxels) and smoothed (8 mm full width at half-maximum).

The fMRI data were modeled using block (Go No-Go and X-CPT) and event-related (Episodic Memory) models. Across all analyses, the six motion parameters were modeled as regressors of no interest to model statistical artifacts associated with motion. In first level analyses for block models, epochs were modeled as separate regressors by convolving with the canonical hemodynamic response function. First level contrast structures were constructed to represent relative differences in activation for negative, neutral and positive conditions. At the first level, these contrasts represent activation differences in each subject for one condition relative to the other. When submitted to second level analyses, comparing BPD patients with healthy controls identified the differential effects of valence in patients compared with controls. Across all second level analyses, these contrast structures allow us to determine the general ordering of valence-related effects in BPD. Consistent with our hypotheses, we focused on effects of non-positive (e.g., negative and neutral) relative to positive emotional contexts. Results are detailed below. (Effects of positive > neutral emotional context can be found in Supplemental Data.) For the event-related analyses, regressors, used to separately represent images of each affective valence, were modeled as individual events convolved with a canonical hemodynamic reference waveform with time and dispersion derivatives (to allow for peak, subject-wise and voxel-wise variations, respectively). First level difference maps were constructed for each subject to isolate selective effects separately associated with encoding or retrieval.

First level maps were submitted to separate second level random effects analyses with group (modeled as an independent factor) and age and gender as covariates. Unique second level models were employed for each class of contrasts.

Directional contrasts using t-tests (BPD <> HC) were used to identify regions of selective hyper- or hypo-reactivity to negative or neutral valence in BPD patients compared with healthy controls. Cluster level correction was performed using established methods (Ward, 2000). 104 Monte Carlo simulations based on the observed smoothness of the data were conducted to derive the minimum cluster extent to be deemed significant for a contiguous set of suprathreshold voxels. Cluster level correction (p<0.05) was applied to identify contiguous voxels in a priori anatomically defined regions of interest, signifying differences across groups (Tzourio-Mazoyer et al., 2002; Maldjian et al., 2003).

2.6. Behavioral data analyses

Behavioral data for all tasks were analyzed in repeated measures analyses of variance with valence context modeled within subjects and group (BPD patients, healthy controls) as the single between-subjects factor. To assess the strength of the effects for each component of the analyses (Main Effects and Interactions), effect sizes are reported as Cohen’s η2, where, by convention, η2>0.02 = small effects; η2>0.13 = medium effects; and η2>0.26 = large effect sizes) (Cohen, 1988; Cohen, 1992).

3. Results

3.1. Subject characteristics

Twenty-three female BPD subjects were compared with15 healthy controls. The mean (SD) age of the sample was 27.1 (6.6) years with no significant difference between groups. Axis I co-morbidity among BPD subjects included the following: 12 subjects (52.2%) with current major depressive disorder and one (4.3%) with current substance abuse. Eleven BPD subjects (47.8%), but no healthy controls, had histories of childhood abuse. Seventeen BPD subjects (73.9%) had histories of medically significant suicide attempts. Eleven BPD subjects (47.8%) were taking one or more psychotropic medications (antidepressants, 9; benzodiazepines, 4; neuroleptics, 2; mood stabilizers, 1).

3.2. fMRI results: affective Go No-Go task (Tables 1 and 2)

Table 1.

Negative > Positive contrasts in BPD and HC subjects

| Anat. ROI | Cluster Ext. | Ind. Cluster Ext. | p uncorrected | Voxel Peak (TAL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A.1. Go-No-Go | HC > BPD | |||

| Mid-Inf OFC. | 70 | 76 | p<0.002 | (−16, −26, −10) Lt.inf.fr. g.BA 47 |

| A.2. Go-No-Go | BPD > HC | |||

| Sup. Parietal | 162 | 626 | p<0.002 | (21, −72, 29) Rt.precuneus BA31 |

| Basal Ganglia | 146 | 537 | p<0.001 | (15, −18, 22) Rt. caudate body |

| Mid-Inf OFC | 146 | 301 | p<0.002 | (−35, 33, −10) Lt. inf. fr. g.BA 47 |

| Hippocampus | 68 | 282 | p<0.001 | (17, −34, 4) Rt. thalamus |

| Amygdala | 36 | 50 | p<0.007 | (−27, −7, −14) Lt. amygdala |

| B.1. Affective CPT | BPD>HC: | |||

| Sup. Parietal | 235 | 2206 | p<0.001 | (−7, −52, 41) Lt. precuneus BA7 |

| ACC | 63 | 1400 | p<0.001 | (3, 42, 6) Rt. ACC |

| Mid-Inf OFC | 147 | 590 | p<0.001 | (−31, 40, −3) Lt. mid. fr. g.BA 11 |

| Hippocampus | 61 | 196 | p<0.010 | (−32, −14, −12) Lt. HIP |

| C.1. Episodic Memory Encoding | HC>BPD | |||

| Hippocampus | 70 | 298 | p<0.001 | (−23, −39, 4) Lt.parahip.BA30 |

| ACC | 162 | 273 | p<0.004 | (−6, 41, 10) Lt. ACC.BA 32 |

| Sup. Parietal | 182 | 235 | p<0.001 | (−15, −42, 45) Lt.precuneus BA7 |

| dPFC | 85 | 125 | p<0.006 | (−50, 17, 27 ) Lt.mid.fr.g.BA9 |

| C.2. Episodic Memory Retrieval | HC > BPD | |||

| ACC | 101 | 149 | p<0.004 | (0, 37, 19) Lt. ACC.BA32 |

| dPFC | 60 | 140 | p<0.006 | (11, 37, 28) Rt. medial fr.g.BA9 |

| Hippocampus | 41 | 51 | p<0.005 | (−32, −28, −3) Lt.caudate tail |

Table 2.

Neutral > Positive contrasts in BPD and HC subjects

| ROI | Cluster Ext. | Ind. Cluster Ext. | p. uncorr. | Voxel Peak (TAL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. 1. Go-No-Go | HC > BPD | |||

| Mid-Inf OFC. | 112 | 137 | p<0.004 | (40, 20, −3) Rt. inf.fr. g. BA 47 |

| A.2. Go-No-Go | BPD > HC | |||

| Sup. Parietal | 162 | 626 | p<0.003 | (−51, −42, 46) Lt. inf.par.g BA40 |

| Basal Ganglia | 111 | 341 | p<0.001 | (19, −18, 22)Rt. caudate body |

| B.1. Affective CPT | HC>BPD: | |||

| Mid-Inf OFC | 89 | 129 | p<0.003 | (34, 32, −4) Rt.inf.fr. g. BA 47 |

| B.2. Affective CPT | BPD>HC: | |||

| Mid-Inf OFC | 80 | 97 | p<0.005 | (29, 46, −13) Rt.mid.fr. g.BA 11 |

| C.1. Episodic Memory Encoding | HC>BPD | |||

| Sup. Parietal | 215 | 945 | p<0.001 | (−33, −48, 38) Lt.inf.par.g. BA 40 |

| Basal Ganglia | 146 | 551 | p<0.001 | (−29, −2, 4) Lt. putamen |

| Hippocampus | 62 | 317 | p<0.001 | (−26, −36, −1) Lt. HIP |

| dPFC | 77 | 221 | p<0.001 | (−44, 39, 12) Lt.inf.fr. g.BA 46 |

| ACC | 164 | 219 | p<0.002 | (9, 36, 17) Rt. ACC.BA 32 |

| Mid-Inf OFC | 102 | 109 | p<0.010 | (−38, 17, −1) Lt. insula BA13 |

| C.2. Episodic Memory Retrieval | HC > BPD | |||

| Basal Ganglia | 155 | 157 | p<0.003 | (−14, 20, 15) Lt.caudate body |

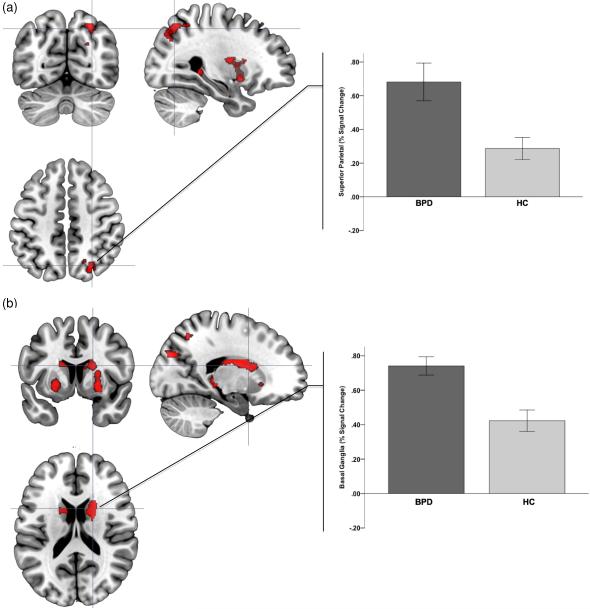

The negative affective context (neg>pos) resulted in significantly increased modulation of brain activity in BPD subjects in multiple regions with significant clusters observed in cortical and sub-cortical structures. These included the superior parietal/precuneus, the basal ganglia, the middle inferior OFC, HIP, and AMY. Fig. 2 plots orthoviews for the most significant peaks in these analyses (superior parietal/precuneus and basal ganglia) with signal changes plotted around (5-mm radius) the significance peaks within the clusters. (This convention is maintained in subsequent figures.) Table 1 provides a comprehensive statistical reporting of these analyses.

Figure 2.

Significance peaks for contrasts identifying hyper-activation to negative (compared to positive epochs) in BPD compared to HC are depicted. These results from the Affective Go-No-Go tasks are rendered on orthoviews (coronal, sagittal, axial) for each of superior parietal cortex (a) and the basal ganglia (caudate nucleus) (b). In each panel, crosshairs are centered on significance peaks in each structure (see Table 1 for information). Radiating graphs depict signal change in the negative context epochs as percent change over signal in the positive context epochs. Error bars are ± sem.

By comparison, a single cluster in the left middle inferior OFC showed decreased activation in BPD (Fig. 3, Table 1).

Figure 3.

Significance peaks for contrasts identifying hypo-activation to negative (compared to positive epochs) in BPD compared to HC are depicted. These results from the Affective Go No-Go task are rendered on orthoviews (coronal, sagittal, axial) for the orbitofrontal cortex. Radiating graphs depict signal change in the negative context epochs as percent change over signal in the positive context epochs. Error bars are ± sem.

Affective interference generalized to the neutral affective context (neutral>pos). Increased activations in BPD were observed in the superior parietal/precuneus and the basal ganglia, and decreased activity in the middle inferior OFC (Table 2).

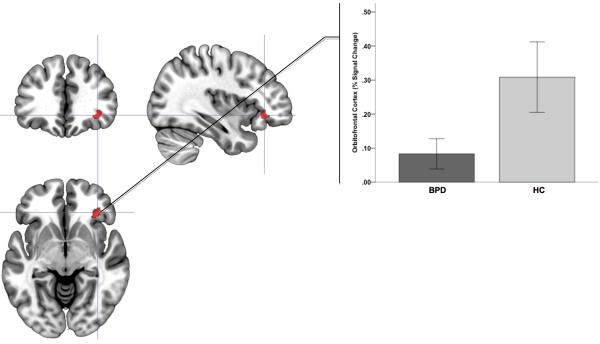

3.3. fMRI results: affective X-CPT task

The patterns of results for the affective X-CPT paradigm were similar to those observed in the Go No-Go paradigm. The negative affective context resulted in significantly increased brain activity in BPD subjects in the superior parietal/precuneus, the ACC, the mid-inferior OFC and the HIP (Fig. 4). The neutral context led to patterns of decreased and increased activations in BPD in the right middle inferior OFC, but with voxel peaks in differing areas (Table 2).

Figure 4.

Significance peaks for contrasts identifying hyper-activation to negative (compared to positive epochs) in BPD compared to HC are depicted. These results from the Affective CPT task are rendered on orthoviews (coronal, sagittal, axial) for each of superior parietal cortex (a) and the anterior cingulate cortex (b). In each panel, crosshairs are centered on significance peaks in each structure (see Table 1 for information). Radiating graphs depict signal change in the negative context epochs as percent change over signal in the positive context epochs. Error bars are ± sem.

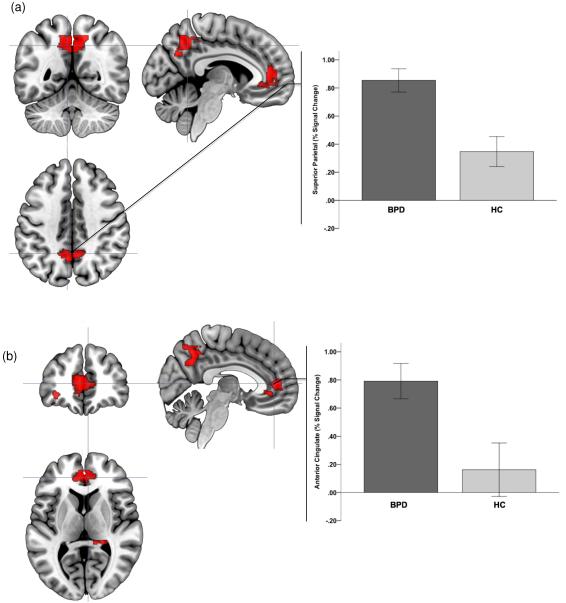

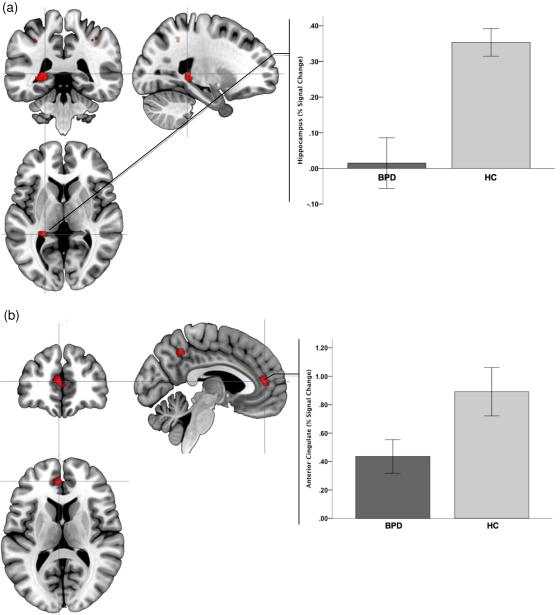

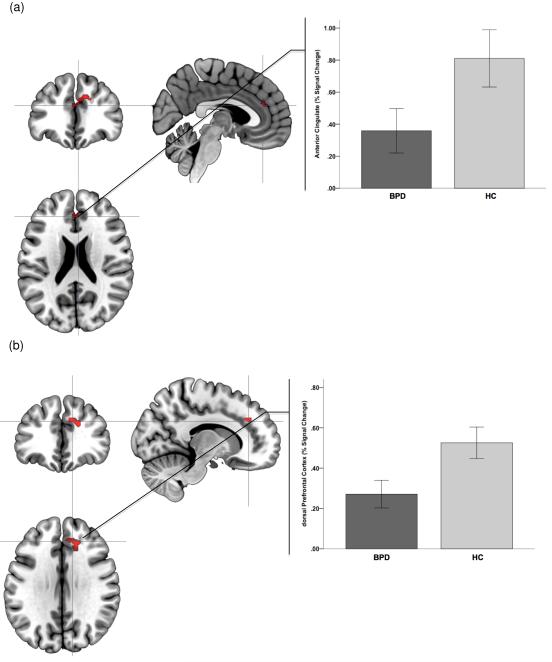

3.4. Affective Episodic Memory task

The directionality of results in the affective Episodic Memory task was distinct from the previous paradigms (in keeping with the different affect-related manipulations). Encoding and retrieval of pictures with negative content diminished activation in multiple regions in BPD patients compared with control subjects. Affected areas included the HIP, the ACC, the superior parietal/precuneus, and the dorsal prefrontal cortex during encoding (Fig. 5), and the ACC, the DLPFC, and the HIP during retrieval (Fig. 6, Table 1).

Figure 5.

Significance peaks for contrasts identifying hypo-activation to negative (compared to positive stimuli) in BPD compared to HC are depicted. These results from the Encoding phase of the Affective Episodic Memory paradigm, and are rendered on orthoviews (coronal, sagittal, axial) for each of the hippocampus regions (a) and the anterior cingulate cortex (b). In each panel, crosshairs are centered on significance peaks in each structure (see Table 1 for information). Radiating graphs depict signal change to the negative stimuli as percent change over signal to the positive stimuli epochs. Error bars are ± sem.

Figure 6.

Significance peaks for contrasts identifying hypo-activation to negative (compared to positive stimuli) in BPD compared to HC are depicted. These results are from the Retrieval phase of the Affective Episodic Memory paradigm. Significance peaks (see Table 1) in the anterior cingulate cortex (a) and the dorsal prefrontal cortex (b) are rendered on orthoviews (coronal, sagittal, axial). Radiating graphs depict signal change to the negative stimuli as percent change over signal to the positive stimuli epochs. Error bars are ± sem.

This pattern of results generalized to the encoding and retrieval of pictures with neutral affective content. BPD subjects showed reduced activation during encoding in the superior parietal/precuneus, the basal ganglia, the HIP, the DLPFC, the ACC, and the middle inferior OFC. During retrieval, decreased activation was noted in BPD subjects in the basal ganglia (Table 2).

When considered with the positive>neutral contrasts (presented in Supplemental Table 1), these analyses suggest that, in BPD, ordering of valence-related effects is Negative > Neutral > Positive. In other words, negative affective context exerted the greatest effect on task-related activations compared with neutral or positive affective context.

3.5. Behavioral results

Differences in behavioral proficiency between clinical and control groups, attributable to the psychiatric disorder, may complicate the interpretation of fMRI-related differences (Carter et al., 2008). Our behavioral results confirmed that the paradigms were easily performed across groups, yet sensitive enough to elicit substantial differences in regional brain activations in BPD. In the affective Go No-Go task, there was a significant effect of affective context, (F3,78=46.81, p<0.001, MSe=0.23), with a very large effect size (η2=0.64). The effects of Group (F1,26=1.51) and the Group × Condition interactions (F3,78=0.24) were not significant, with small effect sizes (η2=0.05 and η2=0.003) (Supplementary Fig. 2). The results for the affective X-CPT task were similar: a significant effect of condition (F3,81=10.71, p<0.001, MSe=0.23), with a large effect size (η2=0.28), but no significant effects for Group (F1,27=0.72) or Group × Condition interactions (F3,81=1.13). Effect sizes were correspondingly small, (η2=0.028 and η2=0.026) (Supplementary Fig. 3). The results for the affective Go No-Go task and the affective X-CPT suggest that the affective context had a highly significant effect on subjects’ abilities to discriminate targets from distracters.

The affective Episodic Memory task was distinct from the other paradigms in its use of images drawn from polar ratings within the IAPS (Lang et al., 1993). The selected pictures were unique and easily discriminable in any short-term episodic memory paradigm. Performance metrics (hit rates and correct rejections) were uniformly high across all subjects and valence types, with no significant differences (Supplementary Figs. 4a, b).

3.6. Effects of psychoactive medication

To assess the effects of psychoactive medication on fMRI results, we repeated all analyses comparing 11 medicated BPD, 12 non-medicated BPD, and 15 control subjects. Signal change analyses across the three fMRI paradigms revealed no significant differences between groups (Supplementary Figs. 5-9).

4. Discussion

We studied the effects of affective context on regional brain activations in BPD, with the specific question as to whether negative context interfered with brain regions specialized for cognitive processing, especially in regions previously reported to have structural or metabolic abnormalities in BPD. We modified three standard cognitive paradigms known to activate these regions by substituting affective faces and pictures for traditionally used stimuli. The single consistent theme across fMRI results of all three paradigms was that negative emotional context selectively impaired the response of each of these regions in BPD relative to control subjects. These results provide convergence with previously demonstrated structural or metabolic abnormalities in BPD, and evidence of task-specific regional effects.

4.1. Mechanisms and convergence with imaging studies in BPD

Affectively valenced stimuli exerted differential effects on regional brain responses in BPD patients compared with control subjects as a function of whether processing demands were predominately attention-driven or stimulus-driven. Attention-driven processing (e.g., affective Go-No-Go and X-CPT) resulted in the hyperactivation of task-related brain networks in areas involved in selective attention (OFC, ACC), response inhibition (OFC), error detection and conflict resolution (ACC), visual and spatial attention (superior parietal/ precuneus), and executive decision-making (OFC, basal ganglia). Attention-driven effects were exaggerated in BPD in both the negative and neutral context (though much more prominently in the negative context). Hyperactivation of these regions may also occur in response to increased “bottom-up” limbic hyperarousal associated with emotion dysregulation in BPD. For example, we observed an area of diminished engagement in the OFC in BPD subjects in concert with increased AMY activation (in the Go No-Go task), putative evidence of diminished “top-down” regulatory effects on emotion (Silbersweig et al., 2007).

In contrast to the attention-driven hyperactivation observed during the Go No-Go task and the X-CPT, hypoactivation was observed during the stimulus-driven affective Episodic Memory task. When participants were not required to direct attention to specific classes of emotional stimuli, BPD subjects showed reduced activation in both negative and neutral affective contexts (compared with positive) during both encoding and retrieval. The diminished activation in the HIP was especially noteworthy as this region is involved in encoding and recall of episodic memory. These results suggest that affective interference with cognitive processing in BPD is driven in part by the stimulus- or attention-driven dynamics of task demand. These dynamics interact with pre-existing imbalances between top-down or bottom-up mechanisms of emotion dysregulation, reflected in structural or metabolic abnormalities.

4.2. Clinical relevance: affective Go No-Go

The Go No-Go paradigm is widely interpreted as a laboratory test of impulsivity and response inhibition, engaging the function of the OFC (Casey et al., 1997; Horn et al., 2003). Among healthy subjects, measures of impulsivity are correlated with specific fMRI activation patterns (especially in right lateral OFC) (Horn et al., 2003). Impulsivity is a core characteristic of BPD, manifested cognitively in impulsive decision-making, and behaviorally in impulsive aggression and self-destructive behavior. In its original format, commission errors on the Go No-Go task discriminate BPD from control subjects (Leyton et al., 2001). BPD and control subjects demonstrate different regions of activation during response inhibition using the standard format (Vollm et al., 2004). In the affective Go No-Go task, however, negative affective context results in +interference with regulatory functions of the OFC, lowering the threshold for emotional and behavioral dyscontrol (Silbersweig et al., 2007; Siever, 2008).

The OFC is broadly involved in the regulation of affect, impulse, and behavior. In concert with the ACC, this region assesses the relevance of external stimuli for responses, focuses attention, directs expression of affect and impulse, and motivates adaptive responses. It is part of a complex neural system (along with the AMY and fusiform gyrus) that assesses emotion in facial expression (Blair et al., 1999). The OFC receives information concerning the internal state of the individual through extensive connections to the limbic system, including reciprocal connections to the AMY (Tekin and Cummings, 2002; Barbas, 2007; Bonelli and Cummings, 2007). BPD is characterized by decreased connectivity between the AMY and the OFC, suggesting a neural vulnerability for diminished regulation of emotion and behavior (New et al., 2007).

Increased activation was found in BPD subjects in the superior parietal/precuneus and basal ganglia in both negative and neutral contrasts in the Go No-Go task (and in the negative contrast in X-CPT) . The superior parietal/precuneus is involved in visuospatial processing, spatial attention, and episodic memory for visual imagery. The precuneus facilitates recall of spatial details of images within working memory and perceptual decision making (Cavanna and Trimble, 2006). Increased activation of the superior parietal /precuneus in BPD subjects in both negative and neutral affective contexts reflects a heightened response to the attention-driven properties of the task independent of affective context. Similar mechanisms are likely to underpin the basal ganglia responses, as this structure is part of the brain’s attention and decision-making network (Herrero et al., 2002; Voytek and Knight, 2010). Structural abnormalities in the basal ganglia have been implicated in impulsive decision-making and even suicidal behavior (Vang et al., 2010; Dombrovski et al., 2012).

4.3. Clinical relevance: affective X-CPT

The affective X-CPT is an attention-demanding task that targets the ACC (Botvinick et al., 2001; Paus, 2001). The dorsal and mid-ACC (in concert with the OFC) are engaged by tasks involving competing choices, error detection, conflict resolution and decision-making (Hoffstaedter et al., 2014). The ventral ACC is more involved in emotion regulation through extensive connections with the AMY, nucleus accumbens, anterior insula, HIP and OFC. Many MRI and PET studies have demonstrated structural and metabolic abnormalities in the ACC among BPD subjects, suggesting a pre-existing vulnerability to impaired function under negative affective stress (De La Fuente et al., 1997; Siever et al., 1999; Leyton et al., 2001; New et al., 2002; Juengling et al., 2003; Tebartz van Elst et al., 2003; Hazlett et al., 2005; Soloff et al., 2008).

4.4. Clinical relevance: affective Episodic Memory task

Human fMRI studies show engagement and connectivity of the HIP and cortical regions during memory formation (Simons and Spiers, 2003; Ranganath et al., 2005; Wadehra et al., 2013). The HIP contributes to declarative, episodic, and working memory functions through extensive connections to the frontal cortex and, as part of the limbic network, processes emotional input from the AMY and related paralimbic structures (Wall and Messier, 2001). These emotional representations are forwarded to higher cortical centers, including the ACC and OFC, supporting emotion regulation.

Both encoding and retrieval of negative and neutral stimuli diminished activation in BPD. This suggests that the affective properties of the stimuli themselves had selective effects on regional brain responses during memory formation and retrieval. The affected areas are involved with working memory (e.g., the DLPFC and precuneus), encoding episodic memory (the HIP), and error detection and control (the ACC) (Chafee and Goldman-Rakic, 2000; Bakshi et al., 2011; Hoffstaedter et al., 2014). Stimulus characteristics that disrupt the functions of these task-relevant regions also impair emotion regulation in BPD. As noted above, MRI and PET studies in BPD provide strong evidence of structural and metabolic abnormalities in these areas.

Diminished volume of the HIP is the most replicated structural MRI abnormality reported in studies of BPD (Ruocco et al., 2012). PET studies using [18F] altanserin (a serotonin-2A receptor antagonist) have demonstrated increased binding to the serotonin-2A receptor in the HIP in female BPD subjects compared with healthy controls, suggesting diminished serotonergic neurotransmission (and compensatory receptor up-regulation or increased affinity) (Soloff et al., 2007). Structural and metabolic abnormalities in the HIP suggest a vulnerability for impaired episodic memory function in subjects with BPD. Delayed recall of episodic autobiographic memory is a characteristic of suicide attempters independent of diagnosis, and it interferes with planning, problem solving, and adaptive coping (Pollock and Williams, 2001).

4.5. Amending the “top down/ bottom-up” model

The “top down/ bottom up” model asserts that emotion dysregulation is mediated by hyperarousal in limbic structures, in the face of diminished regulation from higher cortical regions. If our results were purely driven by this model, we would expect increased activation in the AMY (or associated limbic structures), and decreased activation in the PFC in all three paradigms in BPD patients compared with controls as a result of negative affective interference. Instead, we found that negative emotional context has a differential effect on cognitive processing in BPD subjects depending on the task demands and independent of “top-down/ bottom-up” processing. For example, in the attention-driven Go No-Go paradigm (Neg > Pos), the most robust response in BPD compared with control subjects is increased activation in superior parietal/ precuneus, and basal ganglia, reflecting task-relevant processing. (Diminished activation is also noted among BPD subjects compared with healthy controls in the OFC, and increased in AMY and HIP, consistent with separate and independent “top-down/ bottom-up” processing.)

Focus on negative affective stimuli in the attention-driven X-CPT task (Neg>Pos) produces no areas of diminished cortical activation. On the contrary, increased activations are noted in cortical regions including superior parietal/precuneus, ACC, and OFC, consistent with task demands. The HIP is the only limbic structure that is hyperactivated.

In the stimulus-driven Episodic Memory paradigm, both in encoding and recall of Neg>Pos stimuli, there is no limbic hyperarousal to the negative pictures. Instead, the most robust finding in encoding is diminished activation in the HIP, a limbic region, in BPD subjects compared with controls. Diminished activation is also noted in cortical regions in the ACC, superior parietal/ precuneus and dPFC in encoding, and in ACC and dPFC in retrieval. These cortical effects are consistent with functional impairment of stimulus-driven task-relevant functions.

In BPD subjects, compared with healthy controls, the hyperactivation of task-relevant processes in attention-driven tasks and diminished activation in stimulus-driven tasks during negative affective interference appears independent of “top-down/bottom-up” responses. Differential effects of negative affective interference as a function of task demand should be added to the theoretical model.

We also examined the negative > neutral contrast in all three paradigms (SupplementaryTable 1), and compared results with analyses of the negative > positive and positive > neutral contrasts (Table 1, Supplementary Table 2). For the attention-driven tasks, affective Go No-Go and affective X-CPT, there was extensive overlap in areas of hyperactivation between contrasts, with some variation in laterality and voxel peaks. The magnitude of hyperactivation effects appears to escalate as the stimulus condition becomes more negative. The effects broadly conform to this ordering: negative > neutral >positive. (This is illustrated in a glass brain presentation in Supplementary Fig. 9.). For the stimulus-driven affective Episodic Memory task, during Encoding, the degree of hypoactivation also scales in proportion to the valence of the condition, negative > neutral > positive. However, this pattern was inconsistent during the Episodic Memory-Retrieval phase, where negative, neutral and positive conditions exerted similar effects.

4.6. Limitations

4.6.1. Behavioral effects

Observed differences in fMRI brain responses between BPD and control subjects were similar to previously published fMRI results in BPD, and were not confounded by behavioral differences in task competence or task engagement attributable to the psychiatric disorder (Herpertz et al., 2001; Minzenberg et al., 2007; Koenigsberg et al., 2010). While the effects of negative affect on cognitive processing were markedly different between groups, we found no significant differences between BPD and control subjects in task performance. The absence of behavioral effects is attributable to the simplicity of the task demands, and the relatively low level of affective arousal (i.e., the stimuli were not personally relevant). Affective arousal in PET and fMRI studies of BPD subjects has been “personalized” using self-reported recall of abandonment or trauma experiences, unresolved life events, and even self-injury; however, these studies did not include concurrent cognitive task demands (Schmahl et al., 2003a; Schmahl et al., 2003b; Beblo et al., 2006; Kraus et al., 2010). Silbersweig et al. (2007) demonstrated both brain and behavioral differences between BPD and control subjects using a difficult cognitive task demand (i.e., discriminating emotional words written in italics from words in regular type in a Go No-Go design.) This task may have been more cognitively challenging than discriminating faces or pictures in our study.

With three sequential fMRI tasks, could tiredness have affected behavioral performance? Given the brief duration of the study (a total of 31 min, 25 s), it is unlikely that performance was affected by tiredness. An indirect proof of this is that both groups achieved peak performance on the final Episodic Memory task, with no difference between groups.

4.6.2. Psychoactive medication

Our BPD subjects are representative of symptomatic outpatients with this disorder. All have recent histories of affective instability, impulsivity, aggression, suicidal, or self-injurious behaviors sufficient to support a current diagnosis. The use of psychoactive medication is clinically indicated in many of these subjects. The literature is inconsistent on the effects of psychoactive medication on fMRI results. Among subjects with depression and anxiety disorders, antidepressants normalize aberrant neural responses involved in emotion processing (Outhred et al., 2013). Among subjects with BPD, some studies report no significant effects (or minimal effects) of medication use on fMRI results (Donegan et al., 2003; Beblo et al., 2006; Buchheim et al., 2008). In the emotional linguistic Go No-Go study of Silbersweig et al. (2007), co-variation for medication use did not negate significant differences in fMRI results between BPD and control subjects. However, secondary analyses, which included additional diagnoses, did not survive co-variation for medication status (Silbersweig et al., 2007). We found no significant differences between medicated and unmedicated BPD subjects in signal change analyses across all three fMRI paradigms. However, our ability to detect differences could be affected by reduced power due to small sample sizes.

4.6.3. Sample characteristics

BPD subjects in our sample had significant co-morbidity with major depressive disorder (n=12), childhood abuse (n=11), and suicide attempter status (n=17). We analyzed the brain regions presented in Figs. 2-6 for effects of co-morbidity on %signal change in these regions and found no significant differences between BPD subjects with and without major depressive disorder or childhood abuse. These sub-analyses suggest that our main effects (BPD <> controls) were not confounded by the presence or absence of MDD or childhood abuse in our BPD participants. Understanding the role of depression or childhood abuse was not a central aim of our study, and our sample was underpowered to detect these effects. (Analysis of the effects of suicide attempter status on %signal change in 17 BPD attempters vs. 6 non-attempters was statistically inappropriate.)

Our sample sizes were unbalanced, with 23 BPD subjects compared with 15 healthy controls. The use of t-tests in our statistical analyses was designed to mitigate against the effects of unbalanced sample sizes.

4.7. Conclusions

Negative affective interference with cognitive tasks in BPD subjects is associated with functional abnormalities in brain networks reported to have structural or metabolic abnormalities in BPD. Clinical consequences of functional impairment in the OFC, ACC, and HIP, demonstrated in our three novel paradigms, may include diminished executive functions such as focused attention, decision-making, response inhibition, and episodic memory when disrupted by negative affective context. The borderline patient’s characteristic emotion dysregulation, impulsive-aggression, and self-injurious behavior at times of affective stress may be mediated by the disruptive effects of negative emotion on already vulnerable brain networks.

We found the “top-down/bottom-up” model of emotion dysregulation in BPD insufficient to explain all of the effects of negative emotion on cognitive processing demonstrated in our study. Affective interference with cognitive processing in BPD is driven, in part, by the stimulus- or attention-driven dynamics of task demand. These dynamics interact with pre-existing vulnerabilities in cognitive processing reflected in structural or metabolic abnormalities.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Negative affective interference with cognitive tasks in BPD is associated with functional abnormalities in brain networks known to have structural or metabolic abnormalities.

Emotion dysregulation in BPD may be mediated by the disruptive effects of negative emotion on already vulnerable brain networks.

The “top down/ bottom up” model of emotion dysregulation is insufficient to explain all of the effects of negative emotion on cognitive processing.

Affective interference with cognitive processing in BPD is driven, in part, by the stimulus- or attention-driven dynamics of task demand.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant MH 048063 (PHS), the University of Pittsburgh Magnetic Resonance Research Center (PHS), the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (PHS), the Lycaki-Young Fund from the State of Michigan (VAD), the Prechter World Bipolar Foundation (VAD), and a Career Development Chair from the Office of the President, Wayne State University (VAD).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial disclosure

Paul H. Soloff, Vaibhav A. Diwadkar, Richard White, Amro Omari and Karthik Ramaseshan report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Amaro E, Barker GJ. Study design in fMRI: basic principles. Brain and Cognition. 2006;60:220–232. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) 5th American Psychiatric Publishing; Washington, DC.: 2013. Borderline personality disorder; pp. 663–666. [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi N, Pruitt P, Radwan J, Keshavan MS, Rajan U, Zajac-Benitez C, Diwadkar VA. Inefficiently increased anterior cingulate modulation of cortical systems during working memory in young offspring of schizophrenia patients. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2011;45:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbas H. Flow of information for emotions through temporal and orbitofrontal pathways. Journal of Anatomy. 2007;211:237–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2007.00777.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beblo T, Driessen M, Mertens M, Wingenfeld K, Piefke M, Rullkoetter N, Silva-Saavedra A, Mensebach C, Reddemann L, Rau H, Markowitsch HJ, Wulff H, Lange W, Berea C, Ollech I, Woermann FG. Functional MRI correlates of the recall of unresolved life events in borderline personality disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2006;36:845–856. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706007227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ, Morris JS, Frith CD, Perrett DI, Dolan RJ. Dissociable neural responses to facial expressions of sadness and anger. Brain. 1999;122:883–893. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.5.883. Pt 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJR. The roles of orbital frontal cortex in the modulation of antisocial behavior. Brain and Cognition. 2004;55:198–208. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonelli RM, Cummings JL. Frontal-subcortical circuitry and behavior. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2007;9:141–151. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2007.9.2/rbonelli. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botvinick MM, Braver TS, Barch DM, Carter CS, Cohen JD. Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological Review. 2001;108:624–652. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.3.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brambilla P, Soloff PH, Sala M, Nicoletti MA, Keshavan MS, Soares JC. Anatomical MRI study of borderline personality disorder patients. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2004;131:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchheim A, Erk S, George C, Kachele H, Kircher T, Martius P, Pokorny D, Ruchsow M, Spitzer M, Walter H. Neural correlates of attachment trauma in borderline personality disorder: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2008;163:223–235. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS, Braver TS, Barch DM, Botvinick MM, Noll D, Cohen JD. Anterior cingulate cortex, error detection, and the online monitoring of performance. Science. 1998;280:747–749. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5364.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter CS, Heckers S, Nichols T, Pine DS, Strother S. Optimizing the design and analysis of clinical functional magnetic resonance imaging research studies. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;64:842–849. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Trainor RJ, Orendi JL, Schubert AB, Nystrom LE, Giedd JN, Castellanos FX, Haxby JV, Noll DC, Cohen JD, Forman SD, Dahl RE, Rapoport JL. A developmental functional MRI study of prefrontal activation during performance of a Go-No-Go task. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1997;9:835–847. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.6.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanna AE, Trimble MR. The precuneus: a review of its functional anatomy and behavioural correlates. Brain. 2006;129:564–583. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chafee MV, Goldman-Rakic PS. Inactivation of parietal and prefrontal cortex reveals interdependence of neural activity during memory-guided saccades. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2000;83:1550–1566. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.3.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson RJ, Putnam KM, Larson CL. Dysfunction in the neural circuitry of emotion regulation--a possible prelude to violence. Science. 2000;289:591–594. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5479.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Fuente JM, Goldman S, Stanus E, Vizuete C, Morlan I, Bobes J, Mendlewicz J. Brain glucose metabolism in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1997;31:531–541. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(97)00001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrovski AY, Siegle GJ, Szanto K, Clark L, Reynolds CF, Aizenstein H. The temptation of suicide: striatal gray matter, discounting of delayed rewards, and suicide attempts in late-life depression. Psychological Medicine. 2012;42:1203–1215. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711002133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson DI, Petersen SE, Ollinger JM, Buckner RL. Dissociating state and item components of recognition memory using fMRI. NeuroImage. 2001;13:129–142. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2000.0664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donegan NH, Sanislow CA, Blumberg HP, Fulbright RK, Lacadie C, Skudlarski P, Gore JC, Olson IR, McGlashen TH, Wexler BE. Amygdala hyperreactivity in borderline personality disorder: implications for emotional dysregulation. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:1284–1293. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00636-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessen M, Herrmann J, Stahl K, Zwaan M, Meier S, Hill A, Osterheider M, Petersen D. Magnetic resonance imaging volumes of the hippocampus and the amygdala in women with borderline personality disorder and early traumatization. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:1115–1122. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.12.1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekman P, Friesen WV. Pictures of Facial Affect. Consulting Psychologists Press; Palo Alto, CA: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge LL, Knowlton BJ, Furmanski CS, Bookheimer SY, Engel SA. Remembering episodes: a selective role for the hippocampus during retrieval. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3:1149–1152. doi: 10.1038/80671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders-Patient Edition (SCID-I/P, 4/2005 revision) Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Goyer PF, Andreason PJ, Semple WE, Clayton AH, King AC, Compton-Toth BA, Schultz SC, Cohen RM. Positron-emission tomography and personality disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1994;10:21–28. doi: 10.1038/npp.1994.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross JJ, Thompson RA. Conceptual foundations. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. Guilford Press; New York: 2006. pp. 5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hazlett EA, New AS, Newmark R, Haznedar MM, Lo JN, Speiser LJ, Chen AD, Mitropoulou V, Minzenberg M, Siever LJ, Buchsbaum MS. Reduced anterior and posterior cingulate gray matter in borderline personality disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;58:614–623. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herpertz SC, Dietrich TM, Wenning B, Krings T, Erberich SC, Willmes K, Thron A, Sass H. Evidence of abnormal amygdala functioning in borderline personality disorder: a functional MRI study. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;50:292–298. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrero MT, Barcia C, Navarro JM. Functional anatomy of thalamus and basal ganglia. Child's Nervous System. 2002;18:386–404. doi: 10.1007/s00381-002-0604-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffstaedter F, Grefkes C, Caspers S, Roski C, Palomero-Gallagher N, Laird AR, Fox PT, Eickhoff SB. The role of anterior midcingulate cortex in cognitive motor control: evidence from functional connectivity analyses. Human Brain Mapping. 2014;35:2741–2753. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn NR, Dolan M, Elliott R, Deakin JFW, Woodruff PWR. Response inhibition and impulsivity: an fMRI study. Neuropsychologia. 2003;41:1959–1966. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(03)00077-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irle E, Lange C, Sachsse U. Reduced size and abnormal asymmetry of parietal cortex in women with borderline personality disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;57:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob GA, Guenzler C, Zimmermann S, Scheel CN, Rusch N, Leonhart R, Nerb J, Lieb K. Time course of anger and other emotions in women with borderline personality disorder: a preliminary study. Journal of Behavioral Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2008;39:391–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2007.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Josephs O, Henson RN. Event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging: modelling, inference and optimization. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 1999;354:1215–1228. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juengling FD, Schmahl C, Hesslinger B, Ebert D, Bremner JD, Gostomzyk J, Bohus M, Lieb K. Positron emission tomography in female patients with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2003;37:109–115. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigsberg HW, Fan J, Ochsner KN, Liu X, Guise K, Pizzarello S, Dorantes C, Tecuta L, Guerreri S, Goodman M, New A, Flory J, Siever LJ. Neural correlates of using distancing to regulate emotional responses to social situations. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48:1813–1822. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigsberg HW, Harvey PD, Mitropoulou V, Schmeidler J, New AS, Goodman M, Silverman JM, Serby M, Schopick F, Siever LJ. Characterizing affective instability in borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:784–788. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigsberg HW, Siever LJ, Lee H, Pizzarello S, New AS, Goodman M, Cheng H, Flory J, Prohovnik I. Neural correlates of emotion processing in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2009;172:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus A, Valerius G, Seifritz E, Ruf M, Bremner JD, Bohus M, Schmahl C. Script-driven imagery of self-injurious behavior in patients with borderline personality disorder: a pilot fMRI study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2010;121:41–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01417.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause-Utz A, Winter D, Niedtfeld I, Schmahl C. The latest neuroimaging findings in borderline personality disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2014;16:438. doi: 10.1007/s11920-014-0438-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Cuthbert BN. International Affect Pictures System (IAPS): Technical Manual and Affective Ratings. University of Florida; Gainesville, FL: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Greenwald MK, Bradley MM, Hamm AO. Looking at pictures: affective, facial, visceral, and behavioral reactions. Psychophysiology. 1993;30:261–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1993.tb03352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine D, Marziali E, Hood J. Emotion processing in borderline personality disorders. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1997;185:240–246. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199704000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyton M, Okazawa H, Diksic M, Paris J, Rosa P, Mzengeza S, Young SN, Blier P, Benkelfat C. Brain Regional alpha-[11C]methyl-L-tryptophan trapping in impulsive subjects with borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:775–782. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan M. Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. Guilford Press; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Loranger AW. DSM-IV and ICD-10 Interviews. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.; Lutz, FL: 1999. International Personality Disorder Examination. [Google Scholar]

- Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Kraft RA, Burdette JH. An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. NeuroImage. 2003;19:1233–1239. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam MM. Patterns in behavioral neuroanatomy: association areas, the limbic system, and hemispheic socialization. In: Mesulam MM, editor. Principles of Behavioral Neurology. F.A. Davis; Philadelphia: 1985. pp. 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Minzenberg MJ, Fan J, New AS, Tang CY, Siever LJ. Fronto-limbic dysfunction in response to facial emotion in borderline personality disorder: an event-related fMRI study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2007;155:231–243. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New AS, Hazlett EA, Buchsbaum MS, Goodman M, Mitelman SA, Newmark R, Trisdorfer R, Haznedar MM, Koenigsberg HW, Flory J, Siever LJ. Amygdala-prefrontal disconnection in borderline personality disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1629–1640. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New AS, Hazlett EA, Buchsbaum MS, Goodman M, Reynolds D, Mitropoulou V, Sprung L, Shaw RB, Koenigsberg H, Platholi J, Silverman J, Siever LJ. Blunted prefrontal cortical 18fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography response to meta-chlorophenylpiperazine in impulsive aggression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:621–629. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.7.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedtfeld I, Schmahl CG. Emotion regulation and pain in borderline personality disorder. Current Psychiatry Reviews. 2009;5:48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Gross JJ. The neural architecture of emotion regulation. In: Gross JJ, editor. Handbook of Emotion Regulation. Guilford Press; New York: 2006. pp. 87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Outhred T, Hawkshead BE, Wager TD, Das P, Malhi GS, Kemp AH. Acute neural effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors on emotion processing: Implications for differential treatment efficacy. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2013;37:1786–1800. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T. Primate anterior cingulate cortex: where motor control, drive and cognition interface. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 2001;2:417–424. doi: 10.1038/35077500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips ML, Travis MJ, Fagiolini A, Kupfer DJ. Medication effects in neuroimaging studies of bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:313–320. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07071066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock LR, Williams JM. Effective problem solving in suicide attempters depends on specific autobiographical recall. Suicide and Life Threating Behavior. 2001;31:386–396. doi: 10.1521/suli.31.4.386.22041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranganath C, Heller A, Cohen MX, Brozinsky CJ, Rissman J. Functional connectivity with the hippocampus during successful memory formation. Hippocampus. 2005;15:997–1005. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruocco AC, Amirthavasagam S, Zakzanis KK. Amygdala and hippocampal volume reductions as candidate endophenotypes for borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2012;201:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, van Elst LT, Ludaescher P, Wilke M, Huppertz HJ, Thiel T, Schmahl C, Bohus M, Lieb K, Hesslinger B, Hennig J, Ebert D. A voxel-based morphometric MRI study in female patients with borderline personality disorder. NeuroImage. 2003;20:385–392. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala M, Caverzasi E, Lazzaretti M, Morandotti N, De Vidovich G, Marraffini E, Gambini F, Isola M, De Bona M, Rambaldelli G, d'Allio G, Barale F, Zappoli F, Brambilla P. Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and hippocampus sustain impulsivity and aggressiveness in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;131:417–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmahl CG, Elzinga BM, Vermetten E, Sanislow C, McGlashan TH, Bremner JD. Neural correlates of memories of abandonment in women with and without borderline personality disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2003a;54:142–151. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmahl CG, Vermetten E, Elzinga BM, Bremner JD. Magnetic resonance imaging of hippocampal and amygdala volume in women with childhood abuse and borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2003b;122:193–198. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(03)00023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze L, Domes G, Kruger A, Berger C, Fleischer M, Prehn K, Schmahl C, Grossmann A, Hauenstein K, Herpertz SC. Neuronal correlates of cognitive reappraisal in borderline patients with affective instability. Biological Psychiatry. 2011;69:564–573. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siever LJ. Neurobiology of aggression and violence. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:429–442. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07111774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siever LJ, Buchsbaum MS, New AS, Spiegel-Cohen J, Wei T, Hazlett EA, Sevin E, Nunn M, Mitropoulou V. d,l-fenfluramine response in impulsive personality disorder assessed with [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20:413–423. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silbersweig D, Clarkin JF, Goldstein M, Kernberg OF, Tuescher O, Levy KN, Brendel G, Pan H, Beutel M, Pavony MT, Epstein J, Lenzenweger MF, Thomas KM, Posner MI, Stern E. Failure of frontolimbic inhibitory function in the context of negative emotion in borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1832–1841. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06010126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, Spiers HJ. Prefrontal and medial temporal lobe interactions in long-term memory. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 2003;4:637–648. doi: 10.1038/nrn1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloff PH, Meltzer CC, Becker C, Greer PJ, Kelly TM, Constantine D. Impulsivity and prefrontal hypometabolism in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2003;123:153–163. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(03)00064-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloff PH, Nutche J, Goradia D, Diwadkar V. Structural brain abnormalities in borderline personality disorder: a voxel-based morphometry study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2008;164:223–236. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloff PH, Price JC, Meltzer CC, Fabio A, Frank GK, Kaye WH. 5HT2A receptor binding is increased in borderline personality disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:580–587. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloff PH, Pruitt P, Sharma M, Radwan J, White R, Diwadkar VA. Structural brain abnormalities and suicidal behavior in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2012;46:516–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloff PH, White RA, Diwadkar VA. Impulsivity, aggression and brain structure in high and low lethality suicide attempters with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2014;222:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squire LR, Zola-Morgan S. The medial temporal lobe memory system. Science. 1991;253:1380–1386. doi: 10.1126/science.1896849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tana MG, Montin E, Cerutti S, Bianchi AM. Exploring cortical attentional system by using fMRI during a continuous perfomance test. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience. 2010:329213–329213. doi: 10.1155/2010/329213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tebartz van Elst L, Hesslinger B, Thiel T, Geiger E, Haegele K, Lemieux L, Lieb K, Bohus M, Hennig J, Ebert D. Frontolimbic brain abnormalities in patients with borderline personality disorder: a volumetric magnetic resonance imaging study. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54:163–171. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01743-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tekin S, Cummings JL. Frontal-subcortical neuronal circuits and clinical neuropsychiatry: an update. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2002;53:647–654. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00428-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulving E, Kapur S, Craik FI, Moscovitch M, Houle S. Hemispheric encoding/retrieval asymmetry in episodic memory: positron emission tomography findings. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91:2016–2020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N, Mazoyer B, Joliot M. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. NeuroImage. 2002;15:273–289. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vang FJ, Ryding E, Traskman-Bendz L, van Westen D, Lindstrom MB. Size of basal ganglia in suicide attempters, and its association with temperament and serotonin transporter density. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 2010;183:177–179. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollm B, Richardson P, Stirling J, Elliott R, Dolan M, Chaudhry I, Del Ben C, McKie S, Anderson I, Deakin B. Neurobiological substrates of antisocial and borderline personality disorder: preliminary results of a functional fMRI study. Criminal Behavior and Mental Health. 2004;14:39–54. doi: 10.1002/cbm.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voytek B, Knight RT. Prefrontal cortex and basal ganglia contributions to visual working memory. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:18167–18172. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007277107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadehra S, Pruitt P, Murphy ER, Diwadkar VA. Network dysfunction during associative learning in schizophrenia: increased activation, but decreased connectivity: an fMRI study. Schizophrenia Research. 2013;148:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall PM, Messier C. The hippocampal formation--orbitomedial prefrontal cortex circuit in the attentional control of active memory. Behavioural Brain Research. 2001;127:99–117. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(01)00355-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward BD. AFNI 3dDeconvolve Documentation. Medical College of Wisconsin; Milwaukee: 2000. Simultaneous inference for fMRI data. [Google Scholar]

- Wingenfeld K, Rullkoetter N, Mensebach C, Beblo T, Mertens M, Kreisel S, Toepper M, Driessen M, Woermann FG. Neural correlates of the individual emotional Stroop in borderline personality disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:571–586. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Frankenburg FR, Chauncey DL. The Revised Diagnostic Interview for Borderlines: discriminating BPD from other Axis II disorders. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1989;3:10–18. [Google Scholar]