Abstract

The burgeoning field of epigenetics is making a significant impact on our understanding of brain evolution, development, and function. In fact, it is now clear that epigenetic mechanisms promote seminal neurobiological processes, ranging from neural stem cell maintenance and differentiation to learning and memory. At the molecular level, epigenetic mechanisms regulate the structure and activity of the genome in response to intracellular and environmental cues, including the deployment of cell type–specific gene networks and those underlying synaptic plasticity. Pharmacological and genetic manipulation of epigenetic factors can, in turn, induce remarkable changes in neural cell identity and cognitive and behavioral phenotypes. Not surprisingly, it is also becoming apparent that epigenetics is intimately involved in neurological disease pathogenesis. Herein, we highlight emerging paradigms for linking epigenetic machinery and processes with neurological disease states, including how (1) mutations in genes encoding epigenetic factors cause disease, (2) genetic variation in genes encoding epigenetic factors modify disease risk, (3) abnormalities in epigenetic factor expression, localization, or function are involved in disease pathophysiology, (4) epigenetic mechanisms regulate disease-associated genomic loci, gene products, and cellular pathways, and (5) differential epigenetic profiles are present in patient-derived central and peripheral tissues.

The hallmarks of the human brain are its extraordinary degree of cellular diversity, capacity for synaptic and neural network connectivity and plasticity, and intellectual abilities. Ongoing efforts have sought to better understand this hierarchical organization and the molecular, cellular, and environmental mechanisms responsible for generating it. The completion of the Human Genome Project and the continuing characterization of functional genomic elements (tissue-specific promoters, enhancers, and alternative exons) represent prime advances toward this goal.1,2 This postgenomic era has been defined by the rise of epigenetics—the scientific discipline focused on interrogating how genomic processes, such as gene transcription and DNA replication and repair, are mediated in different cellular contexts.

Epigenetics promises to provide insights that will help answer seminal questions about the human brain. How did it evolve? How does the human genome encode neural cellular diversity? How do genetic factors and environmental stimuli interact to promote synaptic and neural connectivity and plasticity? How do cognitive and behavioral traits emerge? Most importantly, what mechanisms are responsible for the pathogenesis of complex neurological diseases?

Further, the rapidly emerging era of highly personalized epigenetic and epigenomic medicine is poised to radically transform diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for neurological diseases and to deliver innovative treatments to promote neural protection and repair.

The Era of Epigenetics

Revolutionary Insights

Among the most important insights to have emerged is an appreciation for chromatin organization in regulating genomic function and establishing cellular memory states. Chromatin refers to the packaging of the genome within the cell nucleus. DNA is wrapped around a histone protein octamer, forming a fundamental chromatin structure, the nucleosome. Chromatin states play central roles in coordinating the accessibility of DNA sequences to factors in the nucleus mediating critical cellular processes, including gene transcription. Nucleosome-free regions represent DNA actively engaged in regulatory and other functions. These regions can be identified, experimentally, by their relative hypersensitivity to nucleases (DNase I).3 Higher-order chromatin exists as relatively open (euchromatic) or highly condensed (heterochromatic) structures. Euchromatin is generally associated with active transcription, whereas heterochromatin is typically found in inactive regions, such as repressed genes and structural components of chromosomes (centromeres and telomeres). Chromatin structure is dynamic and subject to local modification at the level of individual nucleotides, histone proteins, and nucleosomes and genome-wide by higher-order chromatin remodeling. Protein complexes mediate these processes by the capacity to “read,” “erase,” and “write” specific chromatin states (“marks”). Inhibiting specific chromatin-modifying enzymes is a powerful tool for modulating gene expression programs and a strategy approved by the Food and Drug Administration for select disease indications and now in preclinical and clinical trials for cancer and neurodegenerative diseases.

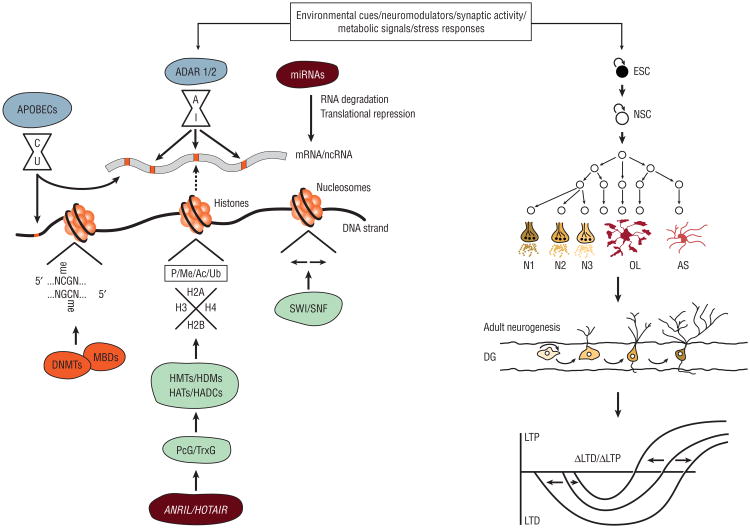

Chromatin states are intimately linked to the establishment and maintenance of cell identity (Figure 1). Chromatin exists in a relatively open conformation in embryonic stem cells, reflecting their pluripotent state. As cellular differentiation proceeds, chromatin becomes more closed, with marks indicative of gene repression, particularly in chromatin associated with pluripotency genes. Conversely, chromatin associated with lineage-specific genes selectively opens and becomes decorated with marks of active gene transcription. Differences in chromatin states explain how the genome gives rise to the plethora of organismal cell types, including the extraordinary diversity of neurons and glia of the human brain. Agents targeting epigenetic enzymes have, therefore, been used to reprogram cell identity and function and may also promote neural regeneration and repair.

Figure 1.

Environmental cues, neuromodulators, synaptic activity, metabolic signals, and stress responses lead to the activation of diverse epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation, histone modifications and chromatin remodeling, noncoding RNA (ncRNA) expression, and RNA editing. In turn, these processes mediate embryonic stem cell (ESC) and neural stem cell (NSC) maintenance and maturation, adult neurogenesis, neural network formation, and synaptic plasticity. Ac indicates acetylation; ADAR, adenosine deaminases that act on RNA enzymes; APOBECs, apolipoprotein B editing catalytic subunit enzymes; AS, astrocyte; C, cytosine; DG, dentate gyrus; DNMTs, DNA methyltransferases; G, guanine; HATs, histone acetylases; HDACs, histone deacetylases; HDMs, histone demethylases; HMTs, histone methyltransferases; LTD, long-term depression; LTP, long-term potentiation; MBDs, methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins; me, methylation; miRNA, microRNA; mRNA, messenger RNA; N, any nucleotide; N1-3, neuronal subtypes 1-3; OL, oligodendrocyte; P, phosphorylation; PcG, Polycomb group proteins; TrxG, Trithorax group proteins; and Ub, ubiquitination.

Another key insight is that the entire human genome is actively transcribed, including regions that code for proteins (<2%) as well as those that do not. Such noncoding regions give rise to numerous classes of noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs)—a previously unexplored layer within the genome—that are interlaced with each other and with protein-coding messenger RNAs (mRNAs). The identification of large numbers of these ncRNAs embedded within the genome and recognition of their important biological roles directly challenges the central dogma of molecular biology (DNA makes RNA and RNA makes protein).

Noncoding RNAs are far more abundant than protein-coding mRNAs in human cells, particularly in neural cells. They engage in complex interactions with DNA, RNA, and proteins and exhibit a spectrum of sophisticated functions. Certain classes of ncRNAs are implicated in gene silencing whereas others are involved in regulating the activity of retrotransposons. Notably, the expression of ncRNAs is most prominent in the brain and subject to intricate temporal and spatial regulation during neural development, homeostasis, and plasticity, highlighting their significance.4 In fact, it is becoming clear that non-coding DNA sequences and associated ncRNAs serve as substrates for evolutionary innovations in the human brain. Human accelerated regions represent elements in the human genome that have evolved rapidly since divergence from our common ancestor with chimpanzees. One of hundreds of such regions, HAR1, gives rise to an ncRNA selectively expressed in Cajal-Retzius cells in the developing fetus and implicated in neuronal subtype specification and cell migration in the neocortex.

Epigenetic Mechanisms

The major epigenetic mechanisms include DNA methylation, histone modifications and nucleosome and higher-order chromatin remodeling, ncRNAs, and RNA editing (Table 1). DNA methylation refers to covalent modification of cytosine residues to form 5-methylcytosine (5mC). 5-Methylcytosine levels are dynamically regulated during development and adulthood. Enzymes that catalyze DNA methylation are DNA methyltransferases; those that catalyze DNA demethylation include DNA excision repair, cytidine deaminase, and Gadd45 proteins. The presence of 5mC at specific gene loci was previously thought to promote transcriptional repression and long-term gene silencing. However, high-resolution genome-wide studies interrogating DNA methylation reveal that 5mC is distributed throughout the genome (gene regulatory regions, transcriptional start sites, gene bodies, and repetitive elements) and DNA methylation seems to be context specific. The effects of DNA methylation are mediated by methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins, including methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2), which bind to 5mC and recruit additional regulatory factors to methylated loci. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine, another modified cytosine residue generated by the Ten-Eleven Trans-location family of enzymes that oxidizes 5mC, appears to counteract 5mC by inhibiting the function of methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins.

Table 1. Principal Epigenetic Mechanisms and Factors.

| Epigenetic Mechanism | Epigenetic Factors |

|---|---|

| DNA (de)methylation and hydroxymethylation | DNA methyltransferase enzymes |

| Methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins | |

| DNA excision repair enzymes | |

| Cytidine deaminase enzymes | |

| Gadd45 proteins | |

| Ten-Eleven Translocation enzymes | |

| Histone and chromatin modifications | Histone-modifying (histone [de]acetylase and [de]methylase) enzymes |

| SWI/SNF nucleosome remodeling complexes | |

| Polycomb group proteins | |

| Trithorax group proteins | |

| RE1-silencing transcription factor | |

| CoREST | |

| Noncoding RNAs | MicroRNAs |

| Small nucleolar RNAs | |

| Endogenous short-interfering RNAs | |

| PIWI-interacting RNAs | |

| Long noncoding RNAs | |

| RNA editing | Adenosine deaminases that act on RNA enzymes |

| Apolipoprotein B editing catalytic subunit enzymes |

Abbreviations: CoREST, corepressor for element-1–silencing transcription factor; RE1, repressor for element-1.

Each nucleosome contains 2 of each core histone protein (H2A, H2B, H3, and H4). Specific classes of histone deacetylases (HDACs) as well as histone acetyltransferases, histone demethylases, histone methyltransferases, and others catalyze histone posttranslational modifications. These enzymes serve as “writers” of posttranslational modifications, thereby altering nucleosome structure and function by modifying interactions with other proteins that “read,” “erase,” and “write” epigenetic marks. Macromolecular complexes containing various proteins with the ability to simultaneously read, erase, and write epigenetic marks promote nucleosome (SWI/SNF) and higher-order chromatin (Polycomb group and Trithorax group proteins) remodeling. Epigenetic regulatory complexes (repressor for element-1 [RE1]–silencing transcription factor [REST] and co-RE1–silencing transcription factor [CoREST] complexes) can also be highly modular and have functions that range from recognizing specific nucleotide sequences and DNA methylation states to promoting local histone and higher-order chromatin modifications.

Newly recognized classes of ncRNAs are classified as short or long. Salient classes of short ncRNAs include microRNAs (miRNAs), endogenous short-interfering RNAs, PIWI-interacting RNAs, and small nucleolar RNAs. Each class is associated with specific biogenesis pathways, mechanisms of action, and functions. MicroRNAs are the best-characterized class of short ncRNAs. They engage in posttranscriptional gene regulation. Specifically, single-stranded, 20- to 23-nucleotide miRNAs bind to protein-coding mRNAs in their 3′ untranslated regions through complementary sequence-specific interactions and prevent translation of these target mRNAs. Importantly, a single miRNA molecule can repress a network of mRNAs. Long ncRNAs (lncRNAs) are the most abundant but least well-characterized class of ncRNAs. The most common strategy for analyzing lncRNAs is to study their genomic context relative to protein-coding genes. Some lncRNAs are derived from intergenic regions (long intergenic/ intervening ncRNAs). Other lncRNAs are transcribed in antisense or overlapping orientations relative to protein-coding genes, and these transcripts are often functionally interrelated. For example, expression of a protein-coding mRNA might be specifically regulated by an antisense lncRNA from the same genomic locus. Nevertheless, lncRNAs are highly versatile with a spectrum of novel activities. These include roles in recruiting non-selective transcriptional and epigenetic regulators to specific loci distributed throughout the genome, forming nuclear bodies, modulating nuclear-cytoplasmic transport, and controlling local protein synthesis at synapses.

RNA editing is a mechanism for modifying RNA molecules. Adenosine-to-inosine editing is catalyzed by adenosine deaminases that act on RNA and cytidine-to-uridine editing is catalyzed by apolipoprotein B editing catalytic subunit enzymes. Intriguingly, cytidine deaminases also act on DNA and are implicated in DNA demethylation pathways (see earlier). RNA editing modifies the information content of RNA molecules and affects their intracellular dynamics. For example, RNA editing can change codons in mRNAs, leading to expression of protein molecules different from those encoded in the genome. This process occurs primarily in proteins involved in neural excitability, such as ion channels and neurotransmitter receptors, and is thought to fine-tune synaptic responsiveness to environmental stimuli. RNA editing also plays a role in controlling the subcellular localization of transcripts. RNAs subject to high levels of editing can be sequestered in nuclear bodies and released in response to specific signals including cellular differentiation, viral infection, and stress. While RNA editing has been studied primarily in protein-coding mRNAs, the majority of RNA editing occurs in noncoding regions. Lastly, RNA editing is much more pronounced in the human brain than in other organ systems and other species, highlighting its responsiveness to environmental stimuli.

Evolving Epigenetic Landscape of Brain

A broad range of studies has focused on elucidating how epigenetic mechanisms together coordinate brain development and functioning throughout the life span, including neural stem cell maintenance and differentiation and synaptic plasticity underlying learning and memory.

Each epigenetic mechanism contributes to the establishment and maintenance of neural cell identity. In fact, the appropriate expression and integrated functional repertoires of DNA methyltransferases, methyl-CpG-binding domain proteins, histone- and chromatin-modifying enzymes, and ncRNA biogenesis factors are necessary for mediating neurogenesis and gliogenesis. Moreover, as embryonic stem cells differentiate into neural lineage-committed progenitors, hundreds of gene promoter regions are methylated, including those associated with pluripotency and alternative lineage genes. These DNA methylation events are responsible for silencing these genes, thereby promoting neural lineage commitment. Histone modifications and chromatin remodeling are similarly involved in establishing neural cell identity. For example, the developmental stage-specific deployment of REST and CoREST complexes modulates neural lineage elaboration, including neuronal and glial subtype specification, and terminal differentiation. In terms of ncRNAs, both miRNAs and lncRNAs regulate neural stem cell self-renewal and differentiation programs. The balance between specific miRNAs is implicated in the execution of these programs. For example, miR-184 promotes neural stem cell proliferation and inhibits neuronal differentiation, whereas miR-9 and miR-137 inhibit neural stem cell proliferation and promote neural differentiation. Other miRNAs, including miR-125b, miR-128, miR-132, miR-134, and miR-138, are associated with neuronal maturation and neural network integration. Long ncRNAs also influence the establishment of neural cell identity. For example, mice lacking the Dlx6 antisense RNA 1 (Dlx6as1) lncRNA have reduced numbers of GABAergic interneurons selectively in the postnatal hippocampus and dentate gyrus, because Dlx6as1 regulates the expression of DLX5 and DLX6, key transcription factors responsible for the development of GABAergic interneurons.5

Epigenetic mechanisms also underpin synaptic plasticity (long-term potentiation and depression) and learning and memory. Each epigenetic mechanism is responsible for regulating genes critical for learning and memory, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor and cAMP responsive element-binding protein. In parallel, these mechanisms can themselves be deployed in response to synaptic activity. Indeed, DNA methylation levels, histone posttranslational modification profiles, ncRNA expression patterns, and RNA editing in hippocampal neurons all vary with memory consolidation and storage. Animal models have also demonstrated the importance of specific epigenetic factors in mediating cognitive and behavioral phenotypes. These exciting studies suggest that modulating the expression and function of epigenetic factors can modulate these processes. For example, Dnmt1 and Dnmt3a double knockout mice exhibit decreases in DNA methylation selectively leading to abnormalities in plasticity in the hippocampal CA1 region and impairments in learning and memory. Furthermore, the DNMT3A2 isoform is involved in age-associated cognitive decline, and upregulation of DNMT3A2 seems to restore cognitive function in mice.6 Similarly, abnormalities in HDAC2-mediated acetylation of histones associated with genes involved in learning and memory contribute to cognitive symptoms in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer disease, and they can be rescued by inhibiting HDAC2 activity.7

Paradigms Linking Epigenetics with Neurological Disease Processes

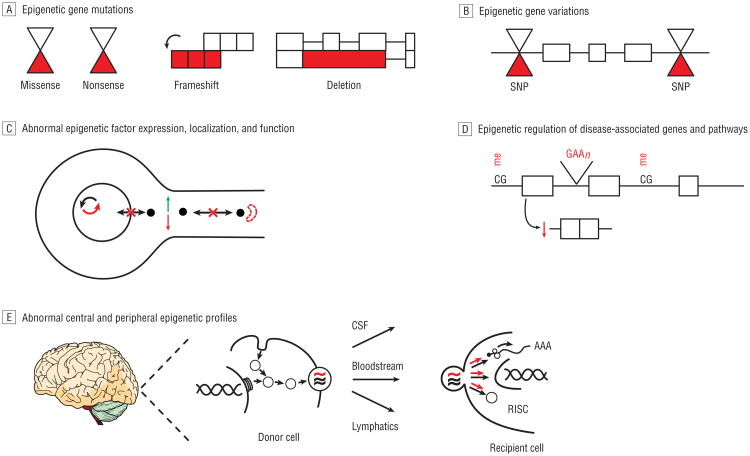

Here, we describe several distinct but nonmutually exclusive paradigms linking epigenetic machinery and mechanisms with neurological disease states (Table 2 and Figure 2). Mutations in genes encoding epigenetic factors can cause neurological disease. Among the most salient examples is the MECP2 gene, which encodes a multifunctional methyl-CpG-binding domain family protein. MECP2 mutations, including missense, nonsense, frameshift, and large deletion mutations, are the primary causes of Rett syndrome, an autism spectrum disorder. MECP2 mutations are also linked to a severe neonatal encephalopathy, syndromic forms of intellectual and developmental disability, and an Angelman-like syndrome. Mutations in other epigenetic factors are similarly associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. For example, mutations in an increasing array of genes encoding proteins that directly and indirectly regulate chromatin structure cause syndromic and nonsyndromic forms of intellectual and developmental disability.8 These emerging observations suggest that disruption of epigenetic networks is one of the principal pathogenic mechanisms underlying intellectual and developmental disability. Mutations in genes encoding epigenetic factors also promote the onset and progression of various forms of cancer, including primary brain tumors. Recent studies have detected a strong association between mutations in the epigenetic machinery—particularly in factors mediating histone lysine (de)methylation—and medulloblastoma.9 These findings are consistent with the observation that the cellular functions of lysine methylation, including roles in regulating cell identity, DNA repair, cell cycle, stress responses, and transcription, are all known to be deregulated in cancer, in general, and medulloblastoma, in particular. These studies implicate many novel genes in medulloblastoma pathogenesis and also correlate specific gene mutations with subgroups of tumors with distinct histological and clinical features, suggesting significant diagnostic, prognostic, and therapeutic value in further characterizing these epigenetic targets.

Table 2. Emerging Paradigms Linking Epigenetic Factors and Mechanisms With Diverse Neurological Disease Processes.

| Paradigms |

|---|

| Mutations in genes encoding epigenetic factors cause disease |

| Genetic variations in genes encoding epigenetic factors modify disease risk |

| Abnormalities in epigenetic factor expression, localization, or function are involved in disease pathophysiology |

| Epigenetic mechanisms regulate disease-associated genomic loci, gene products, and cellular pathways |

| Differential epigenetic profiles are present in patient-derived central and peripheral tissues |

Figure 2.

Emerging paradigms linking epigenetic factors and mechanisms with diverse neurological disease processes. A indicates adenosine; C, cytosine; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; G, guanine; me, methylation; RISC, RNA-induced silencing complex; and SNP, single-nucleotide polymorphism.

Genetic variation in genes encoding epigenetic factors can modify the risk of neurological disease onset and progression. For example, in patients with multiple sclerosis, single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 3 HDAC gene loci—rs2522129 (SIRT4), rs2675231 (HDAC11), and rs2389963 (HDAC9)—are correlated with brain volume measurements on neuroimaging, markers of disease severity.10 In another prominent example, a large genome-wide association study performed by the International Stroke Genetics Consortium demonstrated that a SNP in an intron of the HDAC9 gene (rs11984041) on chromosome 7p21.1 is associated with risk of large-vessel ischemic stroke (odds ratio, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.22-1.57).11 Although the precise pathogenic molecular mechanism is still unclear, HDAC9 is known to play numerous roles in developmental programs and adaptive responses across many organ systems involved in the pathophysiology of atherosclerosis and stroke. Given its intronic location, the effect of this SNP might not simply manifest via the protein-coding gene in which it is embedded. Rather, the risk of large-vessel ischemic stroke might be modified by the effect of this SNP on 1 or more ncRNAs derived from the same locus. Indeed, it is well documented that SNPs within disease-linked genomic loci harboring both protein-coding genes and ncRNA genes can modify disease risk via effects on ncRNA genes. For example, CDKN2B-AS1, also known as ANRIL, is an antisense lncRNA transcribed from the CDKN2B-CDKN2A gene cluster on chromosome 9p21.3. A case-control study demonstrated that SNPs at this locus, including those that preferentially influence expression of ANRIL transcripts, modify the risk of large-vessel ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke and, independently, the risk of recurrent stroke and cardiovascular mortality.12 Emerging data suggest that ANRIL interacts with other epigenetic regulatory factors, including PRC2, and can modulate gene expression programs underpinning diverse cellular processes (proliferation, apoptosis, extracellular matrix remodeling, and inflammation). Notably, other genome-wide association studies have found that the ANRIL locus is a genomic hot spot influencing susceptibility to other disease states affecting the nervous system and beyond.13 These observations highlight the interrelated nature of different epigenetic regulatory processes, their impact on critical cellular programs, and their relevance to disease.

Abnormalities in epigenetic factor expression, localization, or function can be involved in the molecular pathophysiology of neurological disease. Convergence between epigenetic factors and disease-associated pathways and proteins, including those that explicitly cause disease when mutated, results in this kind of deregulation. For example, mutations in the huntingtin protein (HTT), which cause Huntington disease, lead to abnormal profiles of REST expression, localization, and function. RE1-silencing transcription factor is upregulated in Huntington disease and clearly contributes to the transcriptional dysregulation that is a hallmark of the disease. Wild-type HTT modulates the translocation of REST into the neuronal cell nucleus by forming a complex with other factors. Mutant HTT alters the conformation of this complex, leading to aberrant nuclear accumulation of REST.14 In turn, REST-regulated genes, including protein-coding and ncRNA genes, are deregulated in Huntington disease.15 Other proteins that cause disease are similarly involved in modulating the nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of epigenetic factors. The ataxia telangiectasia mutated protein indirectly regulates the subcellular localization of HDAC4.16 Deficiency of ataxia telangiectasia mutated leads to neurodegeneration as a consequence of HDAC4 accumulation in the neuronal cell nucleus. Moreover, inhibiting HDAC4 activity or blocking its nuclear localization can rescue the pathological phenotype. Intriguingly, perturbations of the subcellular localization of HDAC1 that occur in response to inflammatory insults disrupt axonal integrity in animal models of multiple sclerosis, and HDAC1 is mislocalized in regions of demyelination in tissues derived from patients with multiple sclerosis.17 These observations raise the possibility that abnormalities in nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of epigenetic factors represent a common pathogenic mechanism for neuronal damage and loss. In addition to interactions with chromatin regulatory factors, disease-associated pathways and proteins also influence ncRNAs. Mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) that cause familial and sporadic forms of Parkinson disease compromise the integrity of miRNA-mediated translational repression, resulting in deregulation of pathways implicated in Parkinson disease pathogenesis.18 Inhibiting the expression and function of let-7 and miR-184*reproduces these effects in wild-type LRRK2 cells and increasing let-7 and miR-184* expression levels alleviates mutant LRRK2-induced pathology, suggesting that these miRNAs are key players in LRRK2-mediated Parkinson disease pathogenesis. Other disease-associated factors, including fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP), also act cooperatively with the miRNA machinery. FMRP is an RNA-binding protein with a variety of functions including the ability to serve as a translational repressor for target neuronal mRNAs by interacting with select miRNAs and miRNA effector pathways (RNA-induced silencing complex). These pathways are perturbed in fragile X syndrome and related disorders caused by mutations in the gene encoding FMRP. In addition, disease-linked factors affect lncRNAs. TAR DNA-binding protein (TARDBP/TDP-43) is an RNA-binding protein that forms inclusions in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Interestingly, interrogating the profiles of RNAs bound by TDP-43 reveals that the most significant increases in binding in frontotemporal lobar degeneration–TDP are to nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1 (NEAT1) and metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1; also known as NEAT2).19 These lncRNAs localize to nuclear bodies referred to as speckles (NEAT2) and para-speckles (NEAT1) that coordinate the execution of post-transcriptional programs within the nuclear compartment. Speckles contain factors implicated in splicing. By contrast, paraspeckles seem to serve as reservoirs for hyper adenosine-to-inosine edited RNAs that are rapidly exported into the cytoplasm in response to cellular stress. The relationship between TDP-43 and these lncRNAs highlights the importance of TDP-43 for modulating post-transcriptional RNA processing and transport in fronto-temporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Epigenetic mechanisms can regulate disease-associated genomic loci, gene products, and cellular pathways. By definition, epigenetic mechanisms modulate the entire genome, which includes loci involved in the pathogenesis of every neurological disease with a genetic component. Imprinting is the classic example of this phenomenon. It refers to monoallelic gene expression and is mediated by the effects of DNA methylation, histone and chromatin modifications, and ncRNAs that occur at the imprinted locus in a parent-of-origin–dependent manner. Clinical phenotypes associated with perturbations in imprinting on chromosome 15q11-13 include Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes. Additionally, a rapidly increasing number of studies have focused on identifying differential profiles of DNA methylation and histone modifications associated with disease-linked gene loci (in central and peripheral tissues) and correlating these patterns with corresponding gene expression changes and clinical phenotypes. For example, an expansion repeat mutation in the frataxin (FXN) gene causes Friedreich ataxia, and a provocative study analyzed DNA methylation profiles associated with the FXN gene locus in peripheral blood mono-nuclear cells and buccal cells from patients with Friedreich ataxia. It found that DNA methylation upstream of the expansion repeat is correlated with decreased FXN mRNA expression and increased disease severity and also that DNA methylation downstream of the expansion repeat is correlated with age at onset of disease.20 Complementary studies have identified distinct profiles of histone modifications, which likely regulate FXN expression, flanking the mutant FXN expansion repeat in blood as well as the brain and heart, the primary tissues affected in Friedreich ataxia. Another recent study demonstrated that levels of an miRNA, miR-886-3p, are elevated in cell lines and blood samples derived from patients with Friedreich ataxia and that this miRNA plays a role in silencing FXN expression.21 In addition, epigenetic mechanisms regulate genes and pathways involved in disease processes arising from environmental exposures or genetic and environmental interactions. One study focusing on chronic pain syndromes caused by peripheral nervous system injuries demonstrated that C-fiber dysfunction is mediated by decreased levels of sodium channel, voltage-gated, type X, alpha subunit and opioid receptor, mu 1 expression in the dorsal root ganglion and that REST is responsible for the down-regulation of these genes in response to injury.22 Another study using animal models of chronic pain found that persistent painful stimuli led to downregulation of the glutamate decarboxylase 2 gene (Gad2) in pain-modulating neurons of the brainstem nucleus raphe magnus. Hypoacetylation of histones in the Gad2 gene promoter region was responsible for the decreased expression of Gad2, and HDAC inhibition increased GAD2 protein expression and mitigated pain sensitization. In fact, a plethora of evidence suggests that pharmacological agents, such as HDAC inhibitors, can target genes involved in disease-linked processes including apoptosis, blood-brain barrier function, cell-cycle control, DNA repair, excitotoxicity, heat shock, inflammation, oxidative stress, and neurogenesis and gliogenesis. These drugs have significant potential to modify disease pathogenesis and symptoms and are actively being developed for these purposes.

Differential epigenetic profiles can be present in patient-derived central and peripheral tissues. Indeed, a rapidly increasing number of studies have identified differential levels of DNA methylation, histone and chromatin modifications, and ncRNA expression in a spectrum of neurological disorders using patient-derived central and peripheral tissues and animal models. Although the contribution of these aberrant epigenetic profiles to disease processes is sometimes unclear, deregulation of these multilayered epigenetic processes is likely to be responsible, either directly or indirectly, for disease pathophysiology by mediating cross talk between genetic susceptibilities and sex, environment, nutritional states, and aging. These seemingly ubiquitously abnormal signatures may, therefore, have clinical applications as indicators of disease risk, onset, progression, and responsiveness to treatment. For example, the DNA methylation status of genomic repetitive elements in blood correlates with Alzheimer disease and Mini-Mental State Examination scores, stroke and total mortality, and other clinical phenotypes. Moreover, in multiple sclerosis, miRNA expression profiles have been measured in white matter lesions, where they can discriminate between active and inactive lesions, and blood, where they can discriminate between relapsing-remitting and other forms of the disease and patients treated with different therapies (glatiramer acetate and natalizumab) and those who are untreated.23 The secretion of microvesicles, including exosomes, is one interesting mechanism that might explain why peripheral levels of ncRNAs reflect central disease processes. Microvesicles are secreted by donor cells (neural, immune, and other cell types) into cerebrospinal fluid, lymphatics, and blood.24 Microvesicles transfer DNA, RNA, and proteins and can actively “reprogram” recipient cells. For example, transferred miRNAs can silence target mRNAs in recipient cells. The majority of miRNAs found in the peripheral circulation are derived from microvesicles, suggesting that these factors are not simply bystanders but key effectors of dynamic central-peripheral signaling. Long ncRNAs are similarly found in microvesicles and their expression patterns are also deregulated in a range of neurological diseases,25 suggesting that interrogating central and peripheral lncRNA profiles may have diagnostic and prognostic value.

Perspectives

Epigenetics is a swiftly advancing, but nascent, field. Much of the intricacy and nuance surrounding epigenetic mechanisms is yet to be defined fully. Nevertheless, epigenetics has already revolutionized our understanding of how the human brain evolved and how neural cellular diversity, connectivity and plasticity, and advanced intellectual abilities emerge. There is also an evolving literature focused on discovering whether epigenetics is involved in mediating the risk, onset, progression, and treatment responsiveness of neurological diseases. It is becoming clear from these studies that aberrations associated with epigenetic factors, pathways, and profiles can almost always be uncovered, perhaps not surprisingly given the panoramic scope of epigenetics. The contributions of epigenetic abnormalities to neurological disease pathophysiology range from being primary pathogenic mechanisms, protective responses, or simply passenger phenomena. Herein, we have presented one framework for understanding and interpreting neurological disease mechanisms in the context of epigenetics and for promoting the development of paradigm-shifting clinical applications.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Dr Mehler is supported by grants NS071571, HD071593, and MH66290 from the National Institutes of Health, as well as by the F. M. Kirby, Alpern Family, Mildred and Bernard H. Kayden, and Roslyn and Leslie Goldstein foundations.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Qureshi and Mehler. Acquisition of data: Qureshi and Mehler. Analysis and interpretation of data: Qureshi and Mehler. Drafting of the manuscript: Qureshi and Mehler. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Qureshi and Mehler. Obtained funding: Mehler. Administrative, technical, and material support: Mehler. Study supervision: Mehler.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Additional Information: We regret that space constraints have prevented the citation of many relevant and important references.

References

- 1.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, et al. International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409(6822):860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. published correction appears in Nature. 2001;411(6838):720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunham I, Kundaje A, Aldred SF, et al. ENCODE Project Consortium. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489(7414):57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thurman RE, Rynes E, Humbert R, et al. The accessible chromatin landscape of the human genome. Nature. 2012;489(7414):75–82. doi: 10.1038/nature11232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qureshi IA, Mehler MF. Emerging roles of non-coding RNAs in brain evolution, development, plasticity and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(8):528–541. doi: 10.1038/nrn3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bond AM, Vangompel MJ, Sametsky EA, et al. Balanced gene regulation by an embryonic brain ncRNA is critical for adult hippocampal GABA circuitry. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12(8):1020–1027. doi: 10.1038/nn.2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliveira AM, Hemstedt TJ, Bading H. Rescue of aging-associated decline in Dnmt3a2 expression restores cognitive abilities. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(8):1111–1113. doi: 10.1038/nn.3151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gräff J, Rei D, Guan JS, et al. An epigenetic blockade of cognitive functions in the neurodegenerating brain. Nature. 2012;483(7388):222–226. doi: 10.1038/nature10849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Bokhoven H. Genetic and epigenetic networks in intellectual disabilities. Annu Rev Genet. 2011;45:81–104. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110410-132512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson G, Parker M, Kranenburg TA, et al. Novel mutations target distinct subgroups of medulloblastoma. Nature. 2012;488(7409):43–48. doi: 10.1038/nature11213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inkster B, Strijbis EM, Vounou M, et al. Histone deacetylase gene variants predict brain volume changes in multiple sclerosis. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34(1):238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellenguez C, Bevan S, Gschwendtner A, et al. International Stroke Genetics Consortium (ISGC); Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2 (WTCCC2) Genome-wide association study identifies a variant in HDAC9 associated with large vessel ischemic stroke. Nat Genet. 2012;44(3):328–333. doi: 10.1038/ng.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W, Chen Y, Liu P, et al. Variants on chromosome 9p21.3 correlated with ANRIL expression contribute to stroke risk and recurrence in a large prospective stroke population. Stroke. 2012;43(1):14–21. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.625442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pasmant E, Sabbagh A, Vidaud M, Bièche I. ANRIL, a long, noncoding RNA, is an unexpected major hotspot in GWAS. FASEB J. 2011;25(2):444–448. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-172452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimojo M. Huntingtin regulates RE1-silencing transcription factor/neuron-restrictive silencer factor (REST/NRSF) nuclear trafficking indirectly through a complex with REST/NRSF-interacting LIM domain protein (RILP) and dynactin p150 Glued. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(50):34880–34886. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804183200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zuccato C, Belyaev N, Conforti P, et al. Widespread disruption of repressor element-1 silencing transcription factor/neuron-restrictive silencer factor occupancy at its target genes in Huntington's disease. J Neurosci. 2007;27(26):6972–6983. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4278-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J, Chen J, Ricupero CL, et al. Nuclear accumulation of HDAC4 in ATM deficiency promotes neurodegeneration in ataxia telangiectasia. Nat Med. 2012;18(5):783–790. doi: 10.1038/nm.2709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim JY, Shen S, Dietz K, et al. HDAC1 nuclear export induced by pathological conditions is essential for the onset of axonal damage. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13(2):180–189. doi: 10.1038/nn.2471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gehrke S, Imai Y, Sokol N, Lu B. Pathogenic LRRK2 negatively regulates microRNA-mediated translational repression. Nature. 2010;466(7306):637–641. doi: 10.1038/nature09191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tollervey JR, Curk T, Rogelj B, et al. Characterizing the RNA targets and position-dependent splicing regulation by TDP-43. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(4):452–458. doi: 10.1038/nn.2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans-Galea MV, Carrodus N, Rowley SM, et al. FXN methylation predicts expression and clinical outcome in Friedreich ataxia. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(4):487–497. doi: 10.1002/ana.22671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahishi LH, Hart RP, Lynch DR, Ratan RR. miR-886-3p levels are elevated in Friedreich ataxia. J Neurosci. 2012;32(27):9369–9373. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0059-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uchida H, Ma L, Ueda H. Epigenetic gene silencing underlies C-fiber dysfunctions in neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 2010;30(13):4806–4814. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5541-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thamilarasan M, Koczan D, Hecker M, Paap B, Zettl UK. MicroRNAs in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;11(3):174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lai CP, Breakefield XO. Role of exosomes/microvesicles in the nervous system and use in emerging therapies. Front Physiol. 2012;3:228. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qureshi IA, Mattick JS, Mehler MF. Long non-coding RNAs in nervous system function and disease. Brain Res. 2010;1338:20–35. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.03.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]