Fifty years ago this week, Luther Terry, then Surgeon General of the United States, convened a press conference to release the first Surgeon General’s Report on Smoking and Health1. Prior to release, the details of the report were shrouded in secrecy, and a Saturday was chosen to minimize its impact on financial markets. The report—based on review of an estimated 7000 documents—concluded: “cigarette smoking is causally related to lung cancer in men; the magnitude of the effect of cigarette smoking outweighs all other factors; and the risk of developing lung cancer increases with the duration of smoking and number of cigarettes smoked per day, and diminishes by discontinuing smoking.”1.

The impact of the report was enormous, fundamentally changing the way Americans view tobacco use. This first Surgeon General’s report and the 31 that followed it compellingly documented the health risks of smoking, and dramatically influenced public health policy relating to tobacco—breaking the silence surrounding this insidious killer. Despite fierce tobacco industry opposition, the 1964 report prompted Congressional passage of the Federal Cigarette Labeling and Advertising Act of 1965. That law, finally implemented in 1971, mandated that cigarettes carry the warning, “The Surgeon General Has determined That Cigarette Smoking is Dangerous to Your Health.” A ban on advertising of cigarettes on television and radio went into effect in 1970.

While health risks associated with smoking had been documented prior to 1964, widespread public recognition of the risks was lacking. Among the data reviewed by the Surgeon General were two key retrospective investigations by Wynder and Graham2 and Doll and Hill3, which compared smoking histories of persons with and without lung cancer and found much higher rates of smoking among those with lung cancer. Another report by Doll and Hill, a prospective study of British physicians, 62% of whom reported cigarette use—documented a powerful dose-response relationship between the risks of mortality from lung cancer and coronary artery disease and tobacco use4. Other data demonstrated a sharp increase in lung cancer and other tobacco-related deaths since the 1920s that appeared to parallel an increase in cigarette consumption in the United Kingdom and the United States.3,5(p. 227).

Prior to 1900, cigarette smoking was a relatively uncommon behavior. The commercial success of cigarettes in the 20th century was dependent upon several factors including the transition from hand-rolled to machine-rolled cigarettes in the 1880s and the invention of the safety match. Effective promotion and advertising strategies were also key, and included wide distribution of cigarettes to soldiers in both world wars5(p. 52), a broadening of the consumer market to include women, and multiple strategies to allay concerns that smoking might be hazardous. Some of the most influential advertising was directed at women for whom smoking was not a generally acceptable behavior prior to the 1930s. As part of this advertising, women who worried about their waistline were advised to “Reach for a Lucky instead of a Sweet,” among other gender targeted efforts5(p.78). Even physicians succumbed to the lure of tobacco. A 1954 survey of Massachusetts physicians found that–like their patients–more than 50% were daily smokers6. Such data were effectively exploited by the tobacco industry, with popular advertisements in the late 1940s informing the public that “More Doctors Smoke Camels Than Any Other Cigarette.”5(p.105–106)

Despite mounting evidence of health risks from smoking, cigarette manufacturers held steadfast that a relation between tobacco use and disease was nonexistent or controversial, and that smoking was a free choice rather than an addiction – even as internal tobacco industry documents now available for public review7, belie those public stances. No doubt, tobacco industry reassurances led many individuals to continue to smoke, and therefore, suffer premature death and disability.

Since release of the first Surgeon General’s Report, 5 factors in particular contributed to turning the tide against tobacco use in the United States. First, documentation of environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) as a danger to non-smokers in the 1986 Surgeon General’s Report8 substantially compounded the public health risks associated with smoking and led to a flurry of clean indoor air legislation. Currently, 28 states ban smoking in enclosed public spaces. Second, the 1988 Surgeon General’s Report9 documenting tobacco use as an addiction, with nicotine as the primary addictive component, strikingly changed public perceptions of tobacco use from a “habit of free choice” to a true drug dependency, likened by then Surgeon General C. Everett Koop to heroin and cocaine. Third, public policies, most importantly cigarette excise tax increases, clean indoor air laws, and efforts to prevent adolescents from purchasing tobacco and starting to smoke, have proven to be effective tools to drive down tobacco use rates10. Fourth, litigation by private individuals, the states, and the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) pressured the tobacco industry in powerful ways5. The Master Settlement Agreement of 1998 mandating that the tobacco industry pay the states a total of 246 billion dollars over 25 years and the DOJ verdict in 2006 finding the tobacco industry guilty of racketeering were two key legal victories. Finally, evidence-based smoking cessation treatments – both counseling and FDA-approved medications – were documented to markedly increase cessation rates among smokers trying to quit. These treatments, accompanied by an expansion of the physician’s role in treating tobacco use, are now the standard of care for this chief avoidable cause of illness and death in our society11, and are supplemented by the nationwide availability of tobacco cessation telephone quitlines (1-800-QUIT NOW) and web-based cessation strategies (www.smokefree.gov).

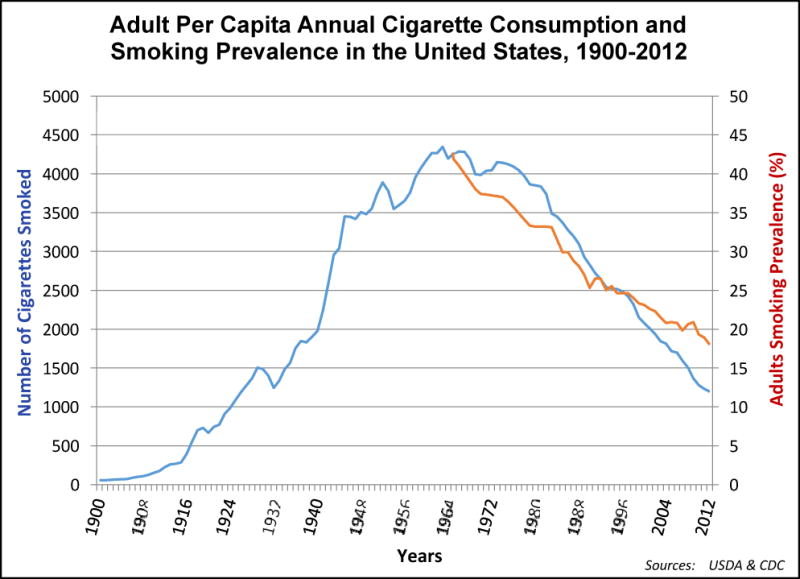

While the overall prevalence of adult smoking in the United States has declined markedly, from 43% in 1964 to an estimated 18% in 2012 with comparable declines in per capita cigarette consumption12 (Figure), higher rates persist among the poor, the least educated, individuals with mental health, substance abuse, and alcohol diagnoses, the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community, and Native Americans. Moreover, on any given day, an estimated 3800 US adolescents smoke their first cigarette, 1,000 of whom will join the ranks of daily (lifetime) cigarette smokers.

Figure.

Smoking remains an unequaled health risk – smokers who are unable to quit die approximately 13 years sooner than never smokers. In total, approximately half a million Americans are killed prematurely each year from diseases directly caused by tobacco use. Finally, tobacco use is economically devastating, costing almost $200 billion annually in added healthcare and lost-productivity costs10. Considered together, these findings attest that a tobacco-free society remains a distant goal.

What can be done to further reduce tobacco use and attain a smoke-free society? History reveals successful strategies that can be further exploited, and the future offers new opportunities – together these provide a roadmap to achieving this outcome. Three strategies offer particular promise. First, certain key policy initiatives have reliably driven down tobacco use rates, suggesting that continued strategic application and expansion of these will accelerate progress. These include: substantial and more inclusive cigarette and cigar excise tax increases, expansion of clean indoor legislation to cover all 50 states, and new and more effective policies to prevent both tobacco purchase and use by minors10. Second, powers inherent in the 2009 federal legislation authorizing the FDA regulation of tobacco13 must be vigorously applied, including: graphic imagery on cigarette packs to highlight health harms from tobacco use; public service campaigns to counter billions of dollars of tobacco industry advertising and promotion; mandated reduction in nicotine content of cigarettes to lessen their addictive grasp on approximately 44 million current smokers; banning menthol from cigarettes; and expanding FDA authority to regulate other tobacco products including cigars and e-cigarettes. Finally, physicians must treat tobacco use with every patient who uses it, as a minimal standard of care11 and healthcare systems must ensure effective and consistent intervention with tobacco users. Tobacco use remains egregiously under treated in healthcare settings. The lethality of tobacco use in the context of readily available and effective cessation treatments makes tobacco treatment a clinical imperative for every patient at every visit. It is time to end the casualties in the tobacco war.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health Education and Welfare. Smoking and Health: Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General of the Public Health Service. Washington, DC: U.S. Departmentof Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service; 1964. (PHS publication No. 1103). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wynder EL, Graham EA. Tobacco smoking as a possible etiologic factor in bronchiogenic carcinoma; a study of 684 proved cases. JAMA. 1950 May 27;143(4):329–336. doi: 10.1001/jama.1950.02910390001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Doll R, Hill AB. Smoking and carcinoma of the lung; preliminary report. Br Med J. 1950 Sep 30;2(4682):739–748. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.4682.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doll R, Hill AB. The mortality of doctors in relation to their smoking habits; a preliminary report. Br Med J. 1954 Jun 26;1(4877):1451–1455. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4877.1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandt AM. The cigarette century. New York: Basic Books; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snegireff LS, Lombard OM. Survey of smoking habits of Massachusetts physicians. N Engl J Med. 1954 Jun 17;250(24):1042–1045. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195406172502408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glantz SA, Barnes DE, Bero L, Hanauer P, Slade J. Looking through a keyhole at the tobacco industry. The Brown and Williamson documents. JAMA. 1995 Jul 19;274(3):219–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of involuntary smoking: A report of the Surgeon General. United States: Public Health Service. Office on Smoking and Health; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking: Nicotine addiction. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Health Interview Survey. Current cigarette smoking among adults aged 18 or older. Early release data: National Health Interview Survey, 1997–September 2012. 2013 http://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/

- 13.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Early release of selected estimates based on data from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/released201306.htm.