Abstract

Healthy lifestyle habits have been associated with improved health outcomes and quality of life and, for some cancers, a reduced risk of recurrence and death. The NCCN Guidelines for Survivorship therefore recommend that cancer survivors be encouraged to achieve and maintain a healthy lifestyle, with attention to weight management, physical activity, and dietary habits. This section of the NCCN Guidelines focuses on recommendations regarding physical activity in survivors, including assessment for the risk of exercise-induced adverse events, exercise prescriptions, guidance for resistance training, and considerations for specific populations (eg, survivors with lymphedema, ostomies, peripheral neuropathy). In addition, strategies to encourage health behavioral change in survivors are discussed.

Healthy Lifestyles

Healthy lifestyle habits, such as engaging in routine physical activity, maintaining a healthy diet and weight, and avoiding tobacco use, have been associated with improved health outcomes and quality of life. For some cancers, a healthy lifestyle has been associated with a reduced risk of recurrence and death.1–6 Therefore, survivors should be encouraged to achieve and maintain a healthy lifestyle, including attention to weight management, physical activity, and dietary habits. Survivors should be advised to limit alcohol intake and avoid tobacco products, with emphasis on tobacco cessation if the survivor is a current smoker or user of smokeless tobacco. Clinicians should also advise survivors to practice sun safety habits as appropriate, such as using a broad-spectrum sunscreen, avoiding peak sun hours, and using physical barriers. Finally, survivors should be encouraged to see a primary care physician regularly and adhere to age-appropriate health screenings, preventive measures (eg, immunizations), and cancer screening recommendations.

The NCCN Panel made specific recommendations regarding physical activity, weight management, nutrition, and supplement use, which are discussed herein. Although achieving all of these healthy lifestyle goals may be difficult for many survivors, even small reductions in weight among overweight or obese survivors or small increases in physical activity among sedentary individuals are thought to yield meaningful improvements in cancer-specific outcomes and overall health.7

Physical Activity

During cancer treatment, many survivors become deconditioned and can develop impaired cardiovascular fitness because of the direct and secondary effects of therapy.8 Randomized trials have shown that exercise training is safe, tolerable, and effective for most survivors. Structured aerobic and resistance training programs after treatment can improve cardiovascular fitness and strength and can have positive effects on balance, body composition, and quality of life.9–17 The effectiveness of exercise training is especially well studied in women with early-stage breast cancer. Survivors of breast cancer who exercise have improved cardiovascular fitness and therefore an increased capacity to perform daily life functions, resulting in a better quality of life.16–20

In addition, observational studies have consistently found that physical activity is linked to decreased cancer incidence and recurrence, and increased survival for certain tumor types.13,21–29 For example, one meta-analysis of 6 studies including more than 12,000 survivors of breast cancer found that postdiagnosis physical activity reduced all-cause mortality by 41% (P<.00001) and disease recurrence by 24% (P=.00001).23 Data from other meta-analyses primarily consisting of observational studies of survivors of colorectal, ovarian, non–small cell lung, brain, prostate, and breast cancers show that physical activity is associated with both decreased all-cause mortality and/or cancer-specific mortality.21,24,28,30 In fact, analyses of data from 986 survivors of breast cancer from the National Runners’ and Walkers’ Health Studies found that mortality decreased with increased rates of energy expenditure.29 Evidence in other disease sites is less robust, but also suggests survival benefits associated with exercise in survivors after treatment.30

Data also support the idea that inactivity/sedentary behavior is a risk factor for cancer incidence and mortality, and impacts mood and quality of life in survivors, independent of the level of an individual’s recreational or occupational physical activity.1,31,32 For example, in a cohort of more than 2000 survivors of nonmetastatic colorectal cancer, those who spent more leisure time sitting had a higher mortality than those who spent more time in recreational activity.1

Evaluation and Assessment for Physical Activity

Survivors should be asked about readiness for participation and their current level of physical activity at regular intervals. The Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire is one tool that can be used to assess a survivor’s exercise behavior, with a modified version also able to assess daily time in moderate-to-vigorous activity.33,34

For survivors who are not meeting the guideline recommendations (see later discussion), barriers to physical activity should be discussed and addressed, if possible. Common barriers include not having enough time to exercise, not having access to an acceptable exercise environment, uncertainty about safety of exercise posttreatment, lack of knowledge regarding appropriate activities, and physical limitations.35 In addition, alleviation of pain, fatigue, distress, or nutritional deficits can facilitate the initiation of an exercise program.

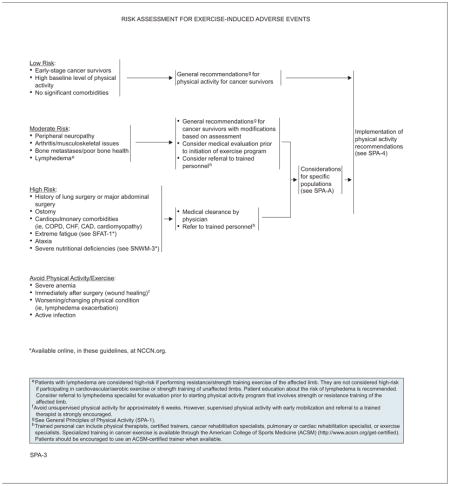

Risk Assessment for Exercise-Induced Adverse Events

Exercise is considered safe for most survivors.16,17,36 However, a significant portion of survivors may have comorbid conditions or risk factors that make them unable to safely exercise without trained supervision.37 Therefore, a risk assessment is required for all survivors before prescribing a specific exercise program.16,38 The type of cancer, treatment modalities received, and the number and severity of comorbidities determine risk levels.36 Thus, disease and treatment history, late and long-term effects, and comorbidities should be assessed. Exercise is typically contraindicated in survivors immediately (≈30 days) after surgery (except for supervised physical activity with early mobilization and referral to a trained therapist) and in those with severe anemia, a worsening condition, or active infection.16,38 A standardized preparticipation screening questionnaire, such as the The Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire for Everyone (PAR-Q+),39 can also be considered to identify patients for whom unsupervised physical activity is likely safe versus those for whom it may pose undue risk.

Survivors with myeloma, peripheral neuropathy, bone metastases, poor bone health, arthritis, or musculoskeletal issues are considered at moderate risk for exercise-induced adverse events. Stability, balance, and gait should be assessed in survivors with peripheral neuropathy before they engage in exercise, and exercise choice should be made based on the results (ie, stationary bike or water aerobics for survivors with poor balance). Survivors with osteoporosis, myeloma, or bone metastases should have fracture risk and/or bone density assessed as clinically indicated before initiating an exercise program. Moderate-risk survivors can often follow the general recommendations for physical activity; however, medical clearance and/or referrals to trained personnel, such as a physical therapist, certified trainer, cancer rehabilitation specialist, pulmonary or cardiac rehabilitation specialist, or exercise specialist, can also be considered. Specialized training in cancer exercise is available through the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM; http://www.acsm.org/get-certified). Survivors should be encouraged to use an ACSM-certified trainer when available.

Survivors at high-risk for exercise-associated adverse events include those with a history of lung surgery or major abdominal surgery, an ostomy, cardiopulmonary comorbidities (eg, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic heart failure, coronary artery disease cardiomyopathy), ataxia, severe nutritional deficiencies, or extreme fatigue. These survivors should receive medical clearance and referral to trained personnel for a supervised exercise program.36 In general, exercise should be individualized to the participant based on current exercise level and medical factors, and should be progressed in terms of intensity, duration, and frequency as tolerated.

Survivors with lymphedema are considered at moderate risk if they are performing resistance/strength-training exercise of the affected limb, but at low risk if they are participating in cardiovascular/aerobic exercise or strength training of unaffected limbs.40–45 Resistance training in survivors with or at risk for lymphedema is discussed in more detail in the section “Resistance and Strength Training,” opposite column.

Physical Activity Recommendations for Survivors

Both the American Cancer Society and the ACSM have made physical activity recommendations for cancer survivors.15,16 The panel supports these recommendations and has adapted them as follows:

All survivors should be encouraged to avoid inactivity or a sedentary lifestyle and return to daily activities as soon as possible.

Survivors who are able should be encouraged to engage in daily physical activity, including exercise, routine activities, and recreational activities.

Physical activity and exercise recommendations should be tailored to individual survivors’ abilities and preferences.

-

General recommendations for cancer survivors:

Overall volume of weekly activity should be at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity, or an equivalent combination

Individuals should engage in 2 to 3 sessions per week of strength training (see next section on “Resistance and Strength Training”) that includes major muscle groups

Major muscle groups should be stretched on the days exercises are performed.

The panel acknowledges that most survivors do not meet these exercise recommendations, and a significant portion report that they perform no leisure-time activity.46,47 However, the evidence suggests that even light-intensity physical activity can improve physical functioning in survivors.48 For survivors who are inactive, clinicians must not advise the immediate initiation of a high-intensity, high-frequency program.49 Instead, the panel suggests that clinicians provide sufficient information to encourage survivors to avoid inactivity.38 The panel recommends starting inactive survivors with 1 to 3 light/moderate-intensity sessions of 20 minutes or more per week, with progression based on tolerance, as outlined in the guidelines.49 For survivors tolerating the minimum guideline recommendations, clinicians should consider encouraging variation within the exercise program or increasing the amount of time engaged in physical activities/exercise modalities. Walking and using a stationary bike are safe for virtually all survivors.

Resistance and Strength Training

The health benefits of resistance training include improvement in muscle strength and endurance, improvements in functional status, and maintenance/improvement in bone density. Studies in survivors have shown improvements in lean body mass, muscular function, and upper body strength.50–53 A recent systematic review of 15 studies of resistance training interventions during and/or after cancer treatment concluded that meaningful improvements in physiologic and quality-of-life outcomes can be achieved.51 A similar review of 11 randomized controlled trials came to similar conclusions.53

Multijoint exercises (eg, chest press, shoulder press, squats, lunges, pushups) are recommended over exercises focused on a single joint, and all major muscle groups (chest, shoulders, arms, back, abdomen, and legs) should be incorporated into a resistance training program. For survivors who do not currently engage in resistance training, clinicians should recommend that they start with 1 set of each exercise and progress up to 2 to 3 sets as tolerated. A weight that would allow the performance of 10 to 15 repetitions is recommended; however, individualizing recommendations for resistance and strength training is important.

Strength training has been shown to be safe for survivors at risk for or with lymphedema, and may even improve lymphedema symptoms.40–44 Still, caution is advised in this population,45 and referral to a lymphedema specialist for evaluation before starting a physical activity program that involves strength or resistance training of the affected limb should be considered. The panel lists special considerations for strength training in this population of survivors in the guidelines, including the use of compression garments, working with a professional trainer, slow progression as tolerated, and baseline and periodic evaluation of lymphedema. The National Lymphedema Network has published a position statement with additional guidance for exercise in individuals with lymphedema.54

Interventions to Increase Physical Activity

Dozens of studies have looked at the efficacy of a variety of behavioral interventions for increasing exercise behavior in cancer survivors.16 However, data comparing different interventions are limited, and there is currently no “best” physical activity program for cancer survivors.55–58 Several studies have examined the physical activity and counseling preferences of survivors, with the goal of informing possible strategies to best encourage increased activity in this population.59–61

The panel suggests several strategies to help increase physical activity. These strategies include a simple recommendation from a physician, physical therapist, and/or certified exercise physiologist.62–64 In addition, participation in supervised exercise programs or classes or use of a pedometer may be helpful for survivors.65–68 Print materials, telephone counseling, motivational counseling, and theory-based behavioral approaches (discussed in the next section) are other strategies that may be effective for increasing physical activity in the survivor population.66,68–72

Health Behavioral Change

Lifestyle behaviors are one area cancer survivors can control if they are encouraged to change and are aware of resources to help them. Ambivalence about changing behavior is common in the general population, but among cancer survivors levels of motivation are often heightened, especially close to the time of diagnosis.10,62,73

Some data suggest that recommendations from the oncologist can carry significant weight for patients with cancer, yet many providers do not discuss healthy lifestyle changes with survivors.62–64 Print materials and telephone counseling are other strategies that may be effective for improving healthy behavior in the survivor population, and several trials show support for these strategies.66,68,71,72 In fact, a recent trial showed that telephone-based health behavior coaching had a positive effect on physical activity, diet, and body mass index in survivors of colorectal cancer.71 Moreover, results of the recently completed Reach Out to Enhance Wellness (RENEW) trial showed that an intervention of telephone counseling and mailed materials in 641 older, obese, and overweight survivors of breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers not only resulted in improved diet quality, weight loss, and physical activity but also had a long-lasting effect that was sustained a year after the intervention was complete.

Another strategy, motivational counseling, may be an effective technique for increasing physical activity and other healthy behaviors in cancer survivors.69,70 Motivational counseling focuses on exploring the survivor’s thoughts, wants, and feelings and is directed at moving through ambivalence so survivors choose to change their behavior.74 Other behavioral strategies may also be useful, such as improving self-efficacy (ie, the belief that one can perform the actions of new activity and maintain this practice by addressing barriers and planning for behavior change) and self-monitoring.75,76

NCCN Survivorship Panel Members

*,a,cCrystal S. Denlinger, MD/Chair†

Fox Chase Cancer Center

*,c,dJennifer A. Ligibel, MD/Vice Chair†

Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center

fMadhuri Are, MD£

Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center at The Nebraska Medical Center

b,eK. Scott Baker, MD, MS€ξ

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance

*,cWendy Demark-Wahnefried, PhD, RD≅

University of Alabama at Birmingham Comprehensive Cancer Center

*,b,d,gDon Dizon, MD†

Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center

b,dDebra L. Friedman, MD, MS€‡

Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center

*,gMindy Goldman, MDΩ

UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center

*,c,dLee Jones, PhDΠ

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

bAllison King, MD€Ψ‡

Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine

eGrace H. Ku, MDξ‡

UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center

*,b,hElizabeth Kvale, MD£

University of Alabama at Birmingham Comprehensive Cancer Center

aTerry S. Langbaum, MAS¥

The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins

gKristin Leonardi-Warren, RN, ND#

University of Colorado Cancer Center

bMary S. McCabe, RN, BS, MS#

Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

b,c,d,gMichelle Melisko, MD†

UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center

*,eJose G. Montoya, MDΦ

Stanford Cancer Institute

a,dKathi Mooney, RN, PhD#

Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah

c,eMary Ann Morgan, PhD, FNP-BC#

Moffitt Cancer Center

Javid J. Moslehi, MDλÞ

Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center

d,hTracey O’Connor, MD†

Roswell Park Cancer Institute

cLinda Overholser, MD, MPHÞ

University of Colorado Cancer Center

cElectra D. Paskett, PhDε

The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center - James Cancer Hospital and Solove Research Institute

Jeffrey Peppercorn, MD, MPH†

Duke Cancer Institute

f,hMuhammad Raza, MD‡

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital/The University of Tennessee Health Science Center

M. Alma Rodriguez, MD‡

The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center

*,fKaren L. Syrjala, PhDθ

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance

*,fSusan G. Urba, MD†£

University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center

gMark T. Wakabayashi, MD, MPHΩ

City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center

*,hPhyllis Zee, MDΨΠ

Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University

NCCN Staff: Nicole R. McMillian, MS, and Deborah A. Freedman-Cass, PhD

KEY:

*Writing Committee Member

Subcommittees: aAnxiety and Depression; bCognitive Function; cExercise; dFatigue; eImmunizations and Infections; fPain; gSexual Function; hSleep Disorders

Specialties: ξBone Marrow Transplantation; λCardiology; εEpidemiology; ΠExercise/Physiology; ΩGynecology/Gynecologic Oncology; ‡Hematology/Hematology Oncology; ΦInfectious Diseases; ÞInternal Medicine; †Medical Oncology; ΨNeurology/Neuro-Oncology; #Nursing; ; ≅Nutrition Science/Dietician; ¥Patient Advocacy; €Pediatric Oncology; θPsychiatry, Psychology, Including Health Behavior; £Supportive Care Including Palliative, Pain Management, Pastoral Care, and Oncology Social Work; ¶Surgery/Surgical Oncology; ωUrology

Footnotes

NCCN Categories of Evidence and Consensus

Category 1: Based upon high-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 2A: Based upon lower-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 2B: Based upon lower-level evidence, there is NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 3: Based upon any level of evidence, there is major NCCN disagreement that the intervention is appropriate.

All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise noted.

Clinical trials: NCCN believes that the best management for any cancer patient is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) are a statement of consensus of the authors regarding their views of currently accepted approaches to treatment. Any clinician seeking to apply or consult the NCCN Guidelines® is expected to use independent medical judgment in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine any patient’s care or treatment. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) makes no representation or warranties of any kind regarding their content, use, or application and disclaims any responsibility for their applications or use in any way. The full NCCN Guidelines for Survivorship are not printed in this issue of JNCCN but can be accessed online at NCCN.org.

© National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. 2014, All rights reserved. The NCCN Guidelines and the illustrations herein may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN.

Disclosures for the NCCN Survivorship Panel

At the beginning of each NCCN Guidelines panel meeting, panel members review all potential conflicts of interest. NCCN, in keeping with its commitment to public transparency, publishes these disclosures for panel members, staff, and NCCN itself.

Individual disclosures for the NCCN Survivorship Panel members can be found on page 1237. (The most recent version of these guidelines and accompanying disclosures are available on the NCCN Web site at NCCN.org.)

These guidelines are also available on the Internet. For the latest update, visit NCCN.org.

| Panel Member | Clinical Research Support/Data Safety Monitoring Board | Advisory Boards, Speakers Bureau, Expert Witness, or Consultant | Patent, Equity, or Royalty | Other | Date Completed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madhuri Are, MD | None | None | None | None | 5/15/13 |

| K. Scott Baker, MD, MS | None | None | None | None | 11/22/13 |

| Wendy Demark-Wahnefried, PhD, RD | National Cancer Institute; American Cancer Society; Harvest for Health Gardening Project for Breast Cancer Survivors; and Nutrigenomic Link between Alpha-Linolenic Acid and Aggressive Prostate Cancer | American Society of Clinical Oncology | None | American Society of Preventive Oncology | 7/13/14 |

| Crystal S. Denlinger, MD | Bayer HealthCare; ImClone Systems Incorporated; MedImmune Inc.; OncoMed Pharmaceuticals; Astex Pharmaceuticals; Merrimack Pharmaceuticals; and Pfizer Inc. | Eli Lilly and Company | None | None | 1/9/14 |

| Don Dizon, MD | None | None | None | American Journal of Clinical Oncology; ASCO; UpToDate | 4/4/14 |

| Debra L. Friedman, MD, MS | None | None | None | None | 7/31/14 |

| Mindy Goldman, MD | None | None | None | Lumetra | 8/23/14 |

| Lee W. Jones, PhD | None | None | Exercise by Science, Inc. | None | 8/21/14 |

| Allison King, MD | None | None | None | None | 8/12/13 |

| Grace H. Ku, MD | None | Seattle Genetics, Inc. | None | None | 5/6/14 |

| Elizabeth Kvale, MD | None | None | None | None | 10/7/13 |

| Terry S. Langbaum, MAS | None | None | None | None | 8/22/14 |

| Kristin Leonardi-Warren, RN, ND | None | None | None | None | 1/6/14 |

| Jennifer A. Ligibel, MD | None | None | None | None | 10/3/13 |

| Mary S. McCabe, RN, BS, MS | None | National Cancer Institute | None | None | 5/6/14 |

| Michelle Melisko, MD | Genentech, Inc.; Celldex Therapeutics; and Galena Biopharma | Agendia BV | None | None | 8/19/14 |

| Jose G. Montoya, MD | None | None | None | None | 12/6/13 |

| Kathi Mooney, RN, PhD | University of Utah | None | None | None | 7/15/14 |

| Mary Ann Morgan, PhD, FNP-BC | None | None | None | None | 5/5/14 |

| Javid J. Moslehi, MD | None | ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; and Pfizer Inc. | None | None | 1/27/14 |

| Tracey O’Connor, MD | None | None | None | None | 6/13/13 |

| Linda Overholser, MD, MPH | None | Antigenics Inc.; and Colorado Central Cancer Registry Care Plan Project | None | None | 10/10/13 |

| Electra D. Paskett, PhD | Merck & Co., Inc. | None | Pfizer Inc. | None | 5/7/14 |

| Jeffrey Peppercorn, MD, MPH | Pending | ||||

| Muhammad Raza, MD | None | None | None | None | 8/23/12 |

| M. Alma Rodriguez, MD | Amgen Inc.; and Ortho Biotech Products, L.P. | None | None | None | 8/5/14 |

| Karen L. Syrjala, PhD | None | None | None | None | 5/1/14 |

| Susan G. Urba, MD | None | Eisai Inc. | None | None | 8/21/14 |

| Mark T. Wakabayashi, MD, MPH | None | None | None | None | 6/19/13 |

| Phyllis Zee, MD | Philips/Respironics | Merck & Co., Inc.; Jazz Pharmaceuticals; Vanda Pharmaceuticals; and Purdue Pharma LP | None | None | 3/26/14 |

References

- 1.Campbell PT, Patel AV, Newton CC, et al. Associations of recreational physical activity and leisure time spent sitting with colorectal cancer survival. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:876–885. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.9735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dignam JJ, Polite BN, Yothers G, et al. Body mass index and outcomes in patients who receive adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1647–1654. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inoue-Choi M, Lazovich D, Prizment AE, Robien K. Adherence to the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research recommendations for cancer prevention is associated with better health-related quality of life among elderly female cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1758–1766. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.4462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee IM, Wolin KY, Freeman SE, et al. Physical activity and survival after cancer diagnosis in men. J Phys Act Health. 2014;11:85–90. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2011-0257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sinicrope FA, Foster NR, Yoon HH, et al. Association of obesity with DNA mismatch repair status and clinical outcome in patients with stage II or III colon carcinoma participating in NCCTG and NSABP adjuvant chemotherapy trials. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:406–412. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wyszynski A, Tanyos SA, Rees JR, et al. Body mass and smoking are modifiable risk factors for recurrent bladder cancer. Cancer. 2014;120:408–414. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hudis CA, Jones L. Promoting exercise after a cancer diagnosis: easier said than done. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:829–830. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lakoski SG, Eves ND, Douglas PS, Jones LW. Exercise rehabilitation in patients with cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2012;9:288–296. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown JC, Huedo-Medina TB, Pescatello LS, et al. Efficacy of exercise interventions in modulating cancer-related fatigue among adult cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:123–133. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Demark-Wahnefried W, Jones LW. Promoting a healthy lifestyle among cancer survivors. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2008;22:319–342. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrer RA, Huedo-Medina TB, Johnson BT, et al. Exercise interventions for cancer survivors: a meta-analysis of quality of life outcomes. Ann Behav Med. 2011;41:32–47. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9225-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fong DY, Ho JW, Hui BP, et al. Physical activity for cancer survivors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2012;344:e70. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones LW, Alfano CM. Exercise-oncology research: past, present, and future. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:195–215. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2012.742564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mishra SI, Scherer RW, Geigle PM, et al. Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD007566. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007566.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:242–274. doi: 10.3322/caac.21142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:1409–1426. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Speck RM, Courneya KS, Masse LC, et al. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:87–100. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Courneya KS, Mackey JR, Bell GJ, et al. Randomized controlled trial of exercise training in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: cardiopulmonary and quality of life outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1660–1668. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markes M, Brockow T, Resch KL. Exercise for women receiving adjuvant therapy for breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD005001. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005001.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNeely ML, Campbell KL, Rowe BH, et al. Effects of exercise on breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2006;175:34–41. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Betof AS, Dewhirst MW, Jones LW. Effects and potential mechanisms of exercise training on cancer progression: a translational perspective. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30:S75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Courneya KS, Sellar CM, Stevinson C, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of aerobic exercise on physical functioning and quality of life in lymphoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4605–4612. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ibrahim EM, Al-Homaidh A. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis: meta-analysis of published studies. Med Oncol. 2011;28:753–765. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9536-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kenfield SA, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci E, Chan JM. Physical activity and survival after prostate cancer diagnosis in the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:726–732. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.5226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ligibel J. Lifestyle factors in cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3697–3704. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.0638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyerhardt JA, Heseltine D, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Impact of physical activity on cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: findings from CALGB 89803. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3535–3541. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyerhardt JA, Ma J, Courneya KS. Energetics in colorectal and prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4066–4073. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.8797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmid D, Leitzmann MF. Association between physical activity and mortality among breast cancer and colorectal cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:1293–1311. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams PT. Significantly greater reduction in breast cancer mortality from post-diagnosis running than walking. Int J Cancer. 2014;135:1195–1202. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ballard-Barbash R, Friedenreich CM, Courneya KS, et al. Physical activity, biomarkers, and disease outcomes in cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:815–840. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ariza-Garcia A, Galiano-Castillo N, Cantarero-Villanueva I, et al. Influence of physical inactivity in psychophysiological state of breast cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2013;22:738–745. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.George SM, Alfano CM, Groves J, et al. Objectively measured sedentary time is related to quality of life among cancer survivors. PLoS One. 2014;9:e87937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DuBose KD, Robinson TS, Rowe DA, Mahar MT. Validation of a modified version of the Godin-Shephard Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire [abstract] Med Sci Sport Exercise. 2006;38 Abstract 2883. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Godin G, Shephard RJ. Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;29(Suppl):S36–38. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blaney JM, Lowe-Strong A, Rankin-Watt J, et al. Cancer survivors’ exercise barriers, facilitators and preferences in the context of fatigue, quality of life and physical activity participation: a questionnaire-survey. Psychooncology. 2013;22:186–194. doi: 10.1002/pon.2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones LW. Evidence-based risk assessment and recommendations for physical activity clearance: cancer. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2011;36(Suppl 1):S101–112. doi: 10.1139/h11-043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown JC, Schmitz KH. The prescription or proscription of exercise in colorectal cancer care. Med Sci Sports. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000355. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wolin KY, Schwartz AL, Matthews CE, et al. Implementing the exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. J Support Oncol. 2012;10:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bredin SS, Gledhill N, Jamnik VK, Warburton DE. PAR-Q+ and ePARmed-X+: new risk stratification and physical activity clearance strategy for physicians and patients alike. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59:273–277. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown JC, John GM, Segal S, et al. Physical activity and lower limb lymphedema among uterine cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:2091–2097. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e318299afd4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Courneya KS, Segal RJ, Mackey JR, et al. Effects of aerobic and resistance exercise in breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4396–4404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayes SC, Speck RM, Reimet E, et al. Does the effect of weight lifting on lymphedema following breast cancer differ by diagnostic method: results from a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130:227–234. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1547-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel A, et al. Weight lifting in women with breast-cancer-related lymphedema. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:664–673. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel AB, et al. Weight lifting for women at risk for breast cancer-related lymphedema: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304:2699–2705. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown JC, Troxel AB, Schmitz KH. Safety of weightlifting among women with or at risk for breast cancer-related lymphedema: musculoskeletal injuries and health care use in a weightlifting rehabilitation trial. Oncologist. 2012;17:1120–1128. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K. Cancer survivors’ adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the American Cancer Society’s SCS-II. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2198–2204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Underwood JM, Townsend JS, Stewart SL, et al. Surveillance of demographic characteristics and health behaviors among adult cancer survivors—Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;61:1–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Blair CK, Morey MC, Desmond RA, et al. Light-intensity activity attenuates functional decline in older cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014;46:1375–1383. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones LW, Eves ND, Peppercorn J. Pre-exercise screening and prescription guidelines for cancer patients. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:914–916. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70184-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Battaglini CL, Mills RC, Phillips BL, et al. Twenty-five years of research on the effects of exercise training in breast cancer survivors: a systematic review of the literature. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5:177–190. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v5.i2.177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Focht BC, Clinton SK, Devor ST, et al. Resistance exercise interventions during and following cancer treatment: a systematic review. J Support Oncol. 2013;11:45–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lonbro S. The effect of progressive resistance training on lean body mass in post-treatment cancer patients: a systematic review. Radiother Oncol. 2014;110:71–80. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Strasser B, Steindorf K, Wiskemann J, Ulrich CM. Impact of resistance training in cancer survivors: a meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2013;45:2080–2090. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31829a3b63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.National Lymphedema Network. [Accessed February 7, 2013];Position Statement of the National Lymphedema Network. Available at: http://www.lymphnet.org/pdfDocs/nlnexercise.pdf.

- 55.Bourke L, Homer KE, Thaha MA, et al. Interventions for promoting habitual exercise in people living with and beyond cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;9:CD010192. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010192.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bourke L, Homer KE, Thaha MA, et al. Interventions to improve exercise behaviour in sedentary people living with and beyond cancer: a systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:831–841. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pinto BM, Ciccolo JT. Physical activity motivation and cancer survivorship. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2011;186:367–387. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-04231-7_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.White SM, McAuley E, Estabrooks PA, Courneya KS. Translating physical activity interventions for breast cancer survivors into practice: an evaluation of randomized controlled trials. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37:10–19. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9084-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Belanger LJ, Plotnikoff RC, Clark A, Courneya KS. A survey of physical activity programming and counseling preferences in young-adult cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2012;35:48–54. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e318210220a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jones LW, Courneya KS. Exercise counseling and programming preferences of cancer survivors. Cancer Pract. 2002;10:208–215. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.104003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stevinson C, Capstick V, Schepansky A, et al. Physical activity preferences of ovarian cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2009;18:422–428. doi: 10.1002/pon.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Demark-Wahnefried W, Aziz NM, Rowland JH, Pinto BM. Riding the crest of the teachable moment: promoting long-term health after the diagnosis of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5814–5830. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jones LW, Courneya KS, Fairey AS, Mackey JR. Effects of an oncologist’s recommendation to exercise on self-reported exercise behavior in newly diagnosed breast cancer survivors: a single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med. 2004;28:105–113. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2802_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sabatino SA, Coates RJ, Uhler RJ, et al. Provider counseling about health behaviors among cancer survivors in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2100–2106. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.6340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, Lipkus IM, et al. Main outcomes of the FRESH START trial: a sequentially tailored, diet and exercise mailed print intervention among breast and prostate cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2709–2718. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Demark-Wahnefried W, Morey MC, Sloane R, et al. Reach out to enhance wellness home-based diet-exercise intervention promotes reproducible and sustainable long-term improvements in health behaviors, body weight, and physical functioning in older, overweight/obese cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2354–2361. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.0895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rajotte EJ, Yi JC, Baker KS, et al. Community-based exercise program effectiveness and safety for cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:219–228. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0213-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vallance JKH, Courneya KS, Plotnikoff RC, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of print materials and step pedometers on physical activity and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2352–2359. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bennett JA, Lyons KS, Winters-Stone K, et al. Motivational interviewing to increase physical activity in long-term cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Nurs Res. 2007;56:18–27. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200701000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Britt E, Hudson SM, Blampied NM. Motivational interviewing in health settings: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;53:147–155. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hawkes AL, Chambers SK, Pakenham KI, et al. Effects of a telephone-delivered multiple health behavior change intervention (CanChange) on health and behavioral outcomes in survivors of colorectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2313–2321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.5873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pinto BM, Frierson GM, Rabin C, et al. Home-based physical activity intervention for breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3577–3587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Satia JA, Campbell MK, Galanko JA, et al. Longitudinal changes in lifestyle behaviors and health status in colon cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1022–1031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Burke BL, Arkowitz H, Menchola M. The efficacy of motivational interviewing: a meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:843–861. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31:143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Short CE, James EL, Plotnikoff RC. How Social Cognitive Theory can help oncology-based health professionals promote physical activity among breast cancer survivors. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;17:482–489. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]