Pain in Survivors

More than one-third of posttreatment cancer survivors experience chronic pain, which often leads to psychological distress; decreased activity, motivation, and personal interactions; and an overall poor quality of life.1-5 Pain in survivors is often ineffectively managed. Barriers to optimal pain management in cancer survivors include health care providers’ lack of training, fear of side effects and addiction, and reimbursement issues.6

Pain has 2 predominant mechanisms: nociceptive and neuropathic.7,8 Injury to somatic and visceral structures and the resulting activation of nociceptors present in skin, viscera, muscles, and connective tissues cause nociceptive pain. Somatic nociceptive pain is often described as sharp, throbbing, or pressure-like, and often occurs after surgical procedures. Visceral nociceptive pain is often diffuse and described as aching or cramping. Neuropathic pain is caused by injury to the peripheral or central nervous system and might be described as burning, sharp, or shooting. Neuropathic pain often occurs as a side effect of chemotherapy or radiation therapy or is caused by surgical injury to the nerves.

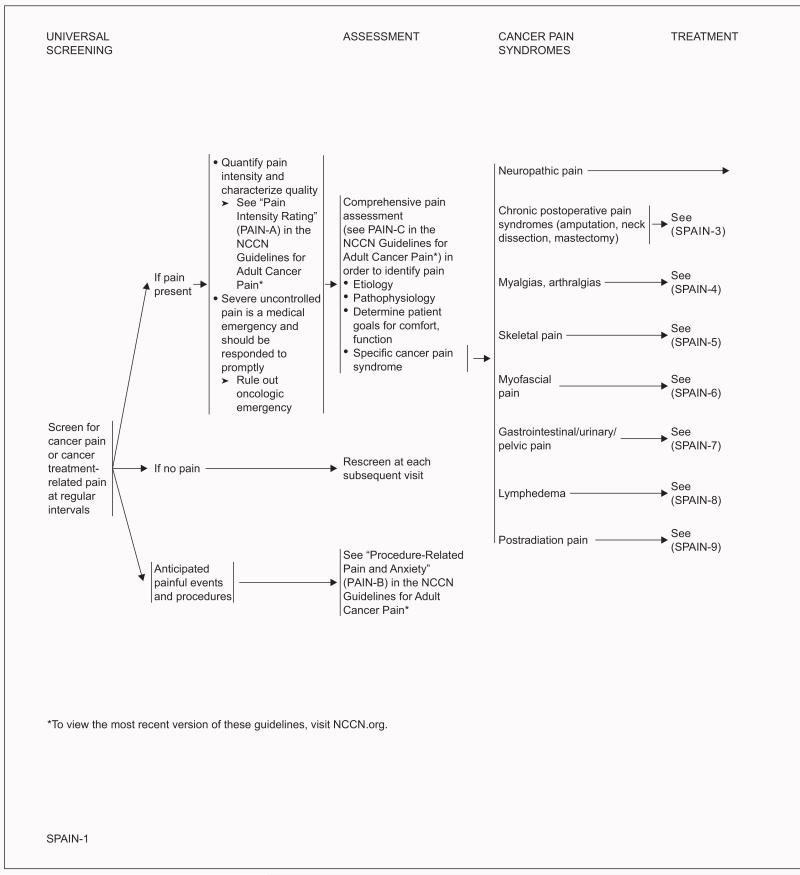

Screening for and Assessment of Pain

All cancer survivors should be screened for pain at regular intervals. If pain is present, the intensity should be quantified by the survivor. Because pain is inherently subjective, self-report of pain is the current standard of care for assessment. Intensity of pain should be quantified using a 0 to 10 numeric rating scale, a categoric scale, or a pictorial scale (eg, Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale).9-12 In addition, the survivor should be asked to describe the characteristics of the pain (eg, aching, burning). Severe uncontrolled pain is a medical emergency and should be responded to promptly. An oncologic emergency also should be ruled out in these cases.

A comprehensive evaluation, as outlined in the NCCN Guidelines for Adult Cancer Pain (available at NCCN.org), is essential to ensure proper pain management. The cause and pathophysiology of the pain should be identified to determine the optimal therapeutic strategy. In addition, the survivor’s goals for comfort and function should be determined.

Management of Pain

The goals of pain management are to increase comfort, maximize function, and improve quality of life. A multidisciplinary approach is recommended, with a combination of pharmacologic treatments, psychosocial and behavioral interventions, physical therapy and exercise, and interventional procedures.2,13,14

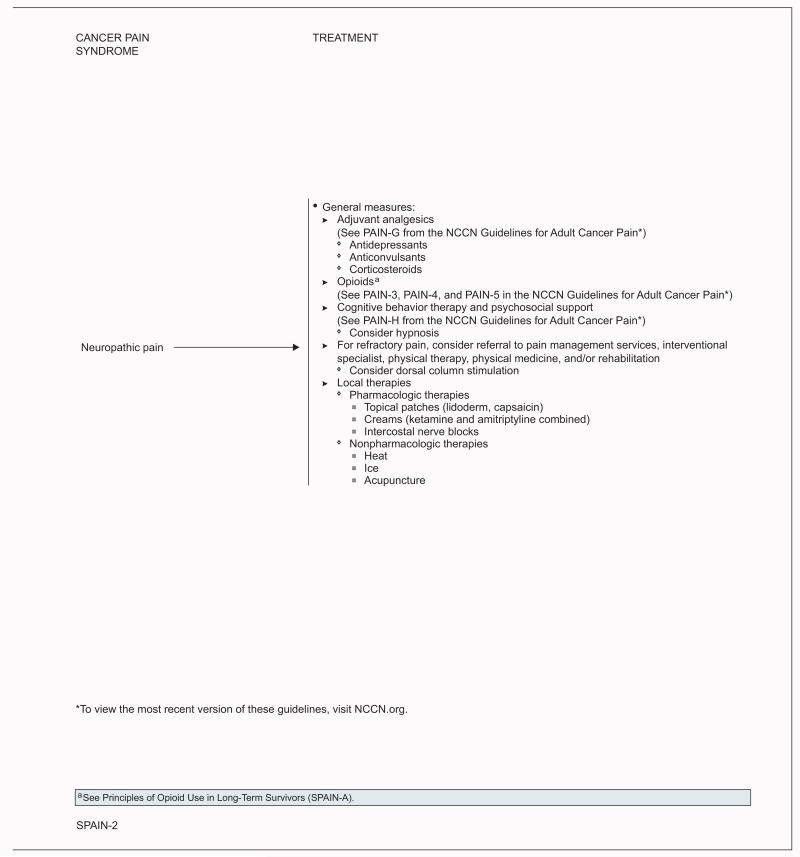

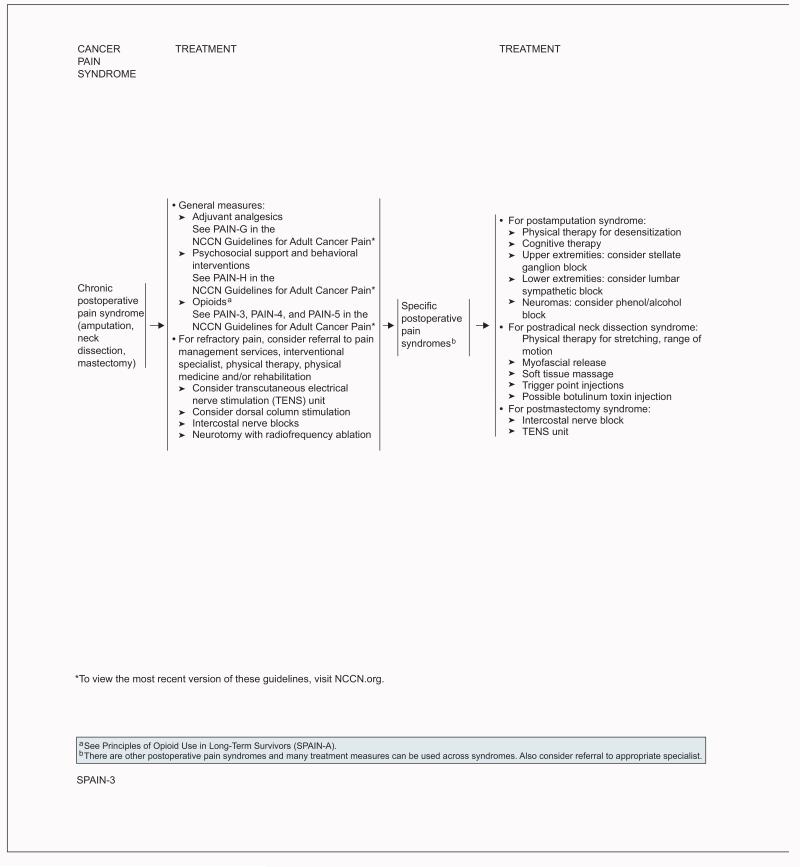

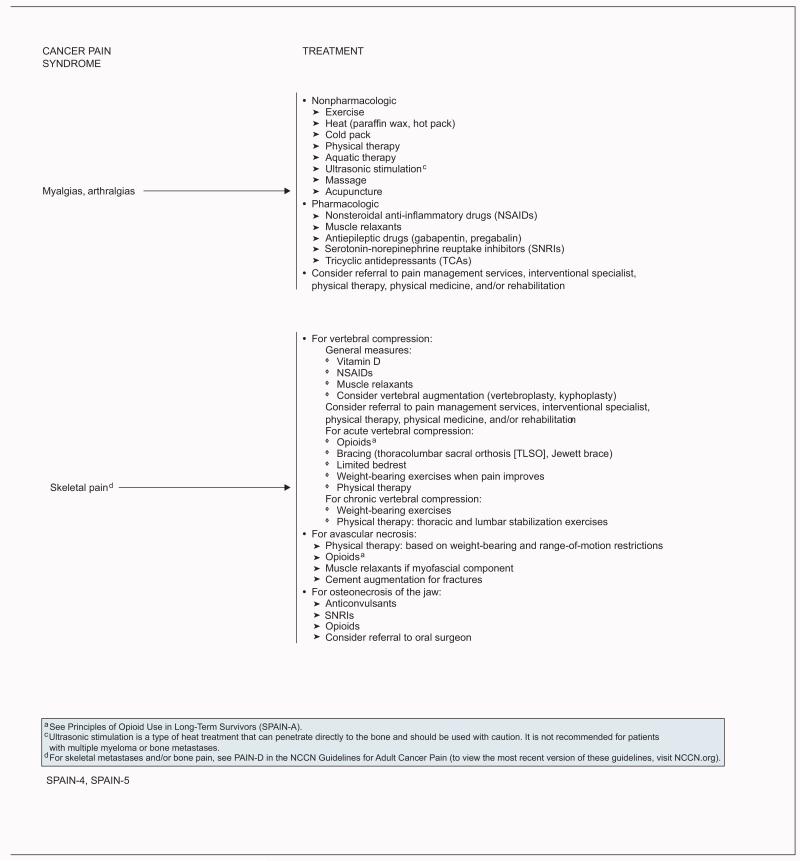

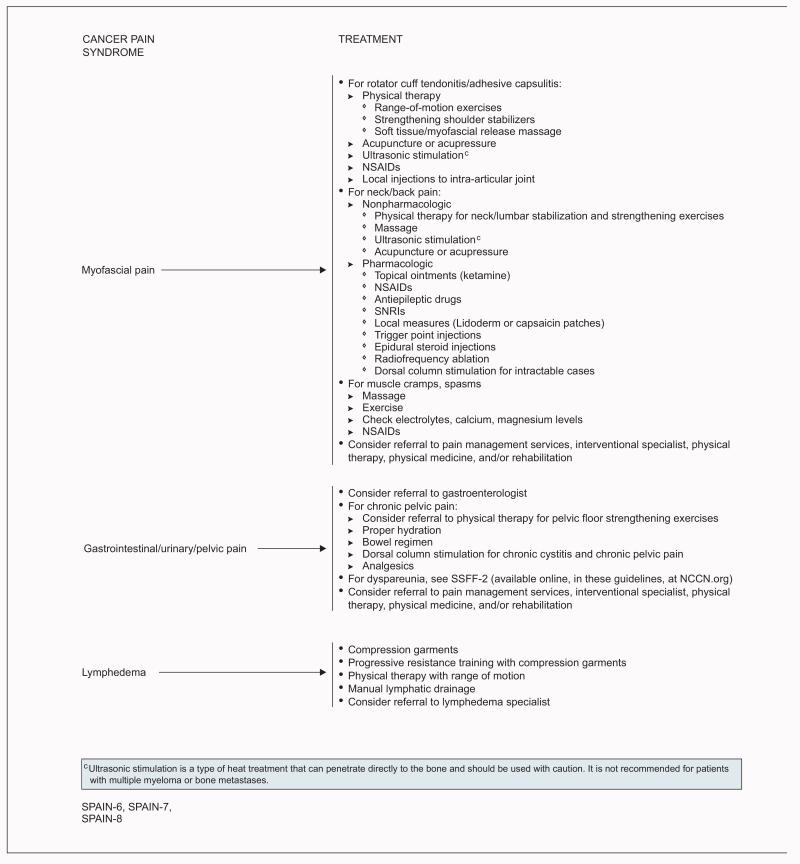

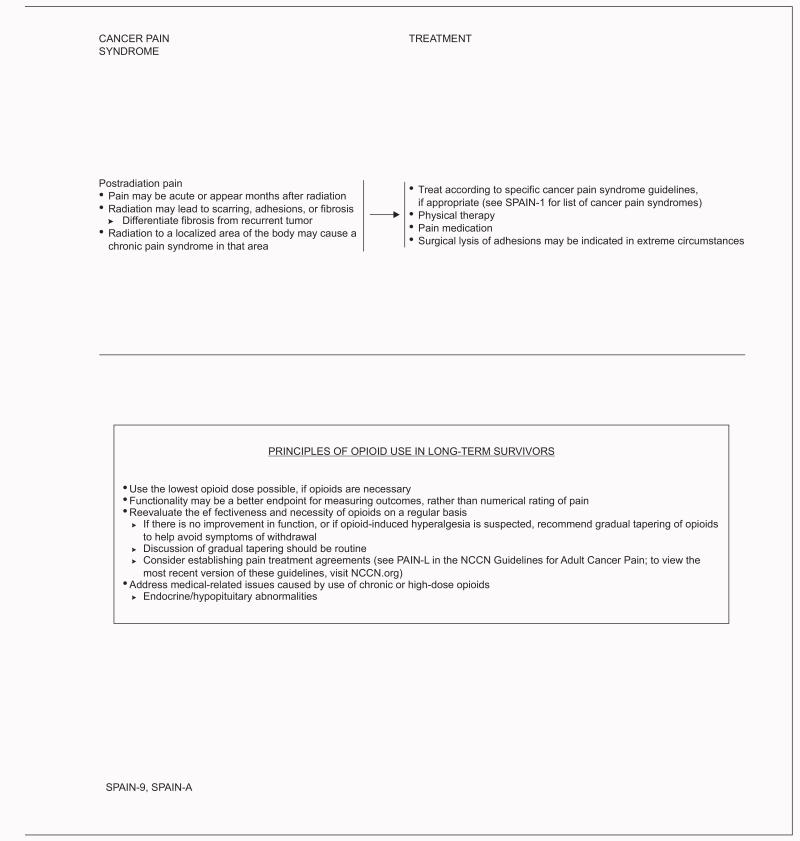

The NCCN Survivorship Panel made recommendations for the management of 8 categories of cancer pain syndromes: neuropathic pain, chronic postoperative pain (ie, pain syndromes after amputation, neck dissection, mastectomy), myalgias/arthralgias, skeletal pain, myofascial pain, gastrointestinal/urinary/pelvic pain, lymphedema, and postradiation pain. Neuropathic pain commonly results from some systemic anticancer agents.1 The incidence of chronic pain after surgical treatment varies with the type of procedure and is as high as 60% in patients treated with breast surgery and 50% in those treated with lung surgery.1 Arthralgias, characterized by joint pain and stiffness, occur in roughly half of women taking aromatase inhibitors as adjuvant therapy for breast cancer.15 Pelvic pain often occurs after pelvic radiation, resulting from fractures, fistulae, proctitis, cystitis, dyspareunia, or enteritis.1

Pharmacologic interventions, local therapies, psychosocial support and behavioral treatments, physical therapy and exercise, and interventional procedures are discussed. For more information about the management of cancer-related pain, please see the NCCN Guidelines for Adult Cancer Pain (to view the most recent version of these guidelines, visit NCCN.org). These guidelines include information on opioid use and pain treatment agreements for patients at risk for medication misuse or diversion; adjuvant analgesics; and psychosocial support and behavioral interventions that may be modified to fit the individual survivor’s circumstances.

Pharmacologic Interventions

Pharmacologic measures are the foundation of treatment of many of the common pain syndromes in survivors. Pharmacologic recommendations in these guidelines vary depending on the pain syndrome and include opioids, adjuvant analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and muscle relaxants.2,16-18 Topical medications are discussed in “Local Therapies” (see page 497).

Opioids

Opioids may be recommended for the treatment of neuropathic, postoperative, and skeletal pain. Data on the long-term use of opioids in survivors are lacking.14,17,19

The NCCN Guidelines for Adult Cancer Pain (available at NCCN.org) recommend screening survivors for risk factors of aberrant opioid use or diversion of pain medication, using a detailed patient evaluation or tools such as the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain-Revised (SOAPP-R) or Opioid Risk Tool (ORT), before prescribing.20-24 In addition, if opioids are deemed necessary for any survivor (regardless of aberrant use risk level), the NCCN Survivorship Panel recommends using the lowest dose possible and reevaluating the effectiveness and necessity of opioids on a regular basis. Pain treatment agreements can also be considered.25

Adjuvant Analgesics

Adjuvant analgesics include antidepressants (eg, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs], tricyclic antidepressants), anticonvulsants (eg, gabapentin, pregabalin), and corticosteroids. These are recommended for the treatment of neuropathic and postoperative pain in survivors. The term adjuvant refers to the fact that they are often coadministered with an opioid to enhance analgesia or reduce the opioid requirement, but they may also be used as sole pain treatment. A recent systematic review found that antidepressants, anticonvulsants, other adjuvant analgesics, and opioids were all effective at reducing neuropathic pain in patients with cancer.17 Another review found that antidepressants and antiepileptics provide additional neuropathic pain relief when added to opioids in patients with cancer.26

Tricyclic antidepressants have been shown to relieve neuropathic pain in the noncancer setting.27,28 In addition, the SNRI duloxetine was recently shown to effectively reduce pain in a multiinstitutional, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial of 231 patients with painful chemotherapy-induced neuropathy.29

The most commonly used anticonvulsant drugs for the treatment of cancer-related pain, gabapentin and pregabalin, have primarily been studied in noncancer neuropathy syndromes.30,31 Only limited data support the effectiveness of corticosteroids for cancer-related pain, and these may also have anti-inflammatory effects.32-34

NSAIDs

NSAIDs are recommended for the treatment of myofascial and skeletal pain and for myalgias and arthralgias. NSAIDs are nonopioid analgesics that block the biosynthesis of prostaglandins, which are inflammatory mediators that initiate, cause, intensify, or maintain pain. A recent systematic review found that data supporting the use of NSAIDs for control of pain in patients with advanced cancer are limited and weak, but suggest some efficacy at reducing pain and opioid dose requirement.35

A discussion of contraindications and safety precautions that should be considered before prescribing NSAIDs is provided in the NCCN Guidelines for Adult Cancer Pain (to view the most recent version of these guidelines, visit NCCN.org).

Muscle Relaxants

Muscle relaxants (eg, diazepam, lorazepam, metaxalone) reduce muscle spasm and are recommended for the treatment of skeletal pain, myalgias, and arthralgias. Evidence for their efficacy in providing pain relief in the noncancer settings is limited.36,37 No data could be found in the setting of cancer-related pain.

Psychosocial Support and Behavioral Interventions

Cognitive interventions are aimed at enhancing a sense of control over the pain or its underlying cause. Breathing exercises, relaxation, imagery or hypnosis, and other behavioral therapies can be very useful.3,38-43 Psychosocial support and education should also be provided.44 Some studies in patients with cancer suggest that psychosocial and behavioral interventions such as skills training, education, relaxation training, supportive–expressive therapy, and cognitive behavioral therapy may be effective at reducing pain.40,45 Hypnosis can also be considered for treatment of neuropathic pain. Overall, data support the benefit of hypnosis for controlling pain in cancer and other settings, but are lacking in the survivorship population.46

In general, studies regarding psychosocial support and behavioral interventions for reducing pain in survivors are limited. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis assessed the efficacy of psychosocial interventions for treating pain in patients with breast cancer and survivors.47 Although results suggest an effect, more studies are clearly needed in the survivorship population.

Physical Therapy and Exercise

Physical therapy and general exercise may also be effective for the treatment of pain in survivors, with the main goal of increasing mobility.3,13,48,49 Several randomized controlled trials have reported a reduction of neck and shoulder pain associated with exercise or therapy programs.50-52 In one study, 52 survivors of head and neck cancer were randomized to a progressive-resistance exercise training (PRET) program or standard therapeutic exercise for 12 weeks.52 Pain scores decreased more dramatically in the PRET group (P=.001). In another study of 66 survivors of breast cancer, those randomized to an 8-week water exercise program experienced a greater reduction of neck and shoulder pain than those randomized to usual care.50 In addition, group exercise in the community, with trainers specifically trained to work with cancer survivors, has been shown to reduce pain and other symptoms.53

Local Therapies

Local therapies, including heat, cold packs, massage, medicated creams, ointments, and patches, are recommended for the treatment of myalgias, arthralgias, and neuropathic and myofascial pain.3 Specifically, topical lidocaine, capsaicin, ketamine, and amitriptyline are recommended for treatment of some of the various cancer pain syndromes. Data are limited on the effectiveness of ketamine and amitriptyline,54-59 but the evidence for the effectiveness of lidocaine and capsaicin is stronger.54,56-58 In a randomized trial of 35 patients with non–cancer-related postherpetic, postoperative, or diabetes-related neuropathic pain, pain intensity was reduced with topical lidocaine but not with topical amitriptyline when compared with placebo.57 A larger trial with a similar population of 92 patients found no effect of topical amitriptyline, ketamine, or a combination of the two.60 Another study found that a higher dose of amitriptyline had some efficacy in reducing peripheral neuropathy, but also showed systemic effects.61 Lidocaine has been shown to reduce the severity of postherpetic neuropathy and cancer-related pain.62,63

Interventional Procedures

Referral to pain management services for interventional procedures, including transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), intercostal nerve blocks, and dorsal column stimulation, is recommended for refractory pain in survivors. Data on the efficacy of these interventions are mainly from patients with active cancer or the noncancer setting.3,64 TENS is a noninvasive procedure with electrodes placed in or around the painful area.3 A recent systematic review found that data supporting the efficacy of TENS for reducing cancer-related pain are inconclusive.65

The goal of invasive interventions, such as an intercostal nerve block, is to interrupt nerve conduction by either destroying nerves or interfering with their function.3 The data on these interventions are also limited.3

Acupuncture

Acupuncture is recommended as an option for the treatment of myofascial pain in survivors. Evidence supporting the efficacy of this technique for reducing cancer-related pain is extremely limited.66,67

Clinical trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any cancer patient is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged. All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise indicated

Version 1.2014, 03-07-14 ©2014 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. All rights reserved. The NCCN Guidelines® and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN®.

Individual Disclosures for the NCCN Survivorship Panel.

| Panel Member | Clinical Research Support/Data Safety Monitoring Board |

Advisory Boards, Speakers Bureau, Expert Witness, or Consultant |

Patent, Equity, or Royalty |

Other | Date Completed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madhuri Are, MD | None | None | None | None | 5/15/13 |

| K. Scott Baker, MD, MS | None | None | None | None | 11/22/13 |

| Wendy Demark-Wahnefried, PhD, RD | National Cancer Institute; Harvest for Health Gardening Project for Breast Cancer Survivors; and Nutrigenomic Link between Alpha- Linolenic Acid and Aggressive Prostate Cancer |

American Society of Clinical Oncology |

None | American Society of Preventive Oncology |

11/13/13 |

| Crystal S. Denlinger, MD | Bayer HealthCare; ImClone Systems Incorporated; MedImmune Inc.; OncoMed Pharmaceuticals; Astex Pharmaceuticals; Merrimack Pharmaceuticals; and Pfizer Inc. |

Eli Lilly and Company | None | None | 1/9/14 |

| Debra L. Friedman, MD, MS | None | None | None | None | 5/26/13 |

| Mindy Goldman, MD | Pending | ||||

| Lee W. Jones, PhD | None | None | None | None | 2/2/12 |

| Allison King, MD | None | None | None | None | 8/12/13 |

| Grace H. Ku, MD | None | None | None | None | 8/13/13 |

| Elizabeth Kvale, MD | None | None | None | None | 10/7/13 |

| Terry S. Langbaum, MAS | None | None | None | None | 8/13/13 |

| Kristin Leonardi-Warren, RN, ND | None | None | None | None | 1/6/14 |

| Jennifer A. Ligibel, MD | None | None | None | None | 10/3/13 |

| Mary S. McCabe, RN, BS, MS | None | None | None | None | 8/12/13 |

| Michelle Melisko, MD | Celldex Therapeutics; and Galena Biopharma |

Agendia BV; Genentech, Inc.; and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation |

None | None | 10/11/13 |

| Jose G. Montoya, MD | None | None | None | None | 12/6/13 |

| Kathi Mooney, RN, PhD | University of Utah | None | None | None | 9/30/13 |

| Mary Ann Morgan, PhD, FNP-BC | None | None | None | None | 8/19/13 |

| Javid J. Moslehi, MD | None | ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; and Pfizer Inc. |

None | None | 1/27/14 |

| Tracey O’Connor, MD | None | None | None | None | 6/13/13 |

| Linda Overholser, MD, MPH | None | Antigenics Inc.; and Colorado Central Cancer Registry Care Plan Project |

None | None | 10/10/13 |

| Electra D. Paskett, PhD | Merck & Co., Inc. | None | None | None | 6/13/13 |

| Muhammad Raza, MD | None | None | None | None | 8/23/12 |

| Karen L. Syrjala, PhD | None | None | None | None | 10/3/13 |

| Susan G. Urba, MD | None | Eisai Inc.; and Helsinn Therapeutics (U.S.), Inc. |

None | None | 10/9/13 |

| Mark T. Wakabayashi, MD, MPH | None | None | None | None | 6/19/13 |

| Phyllis Zee, MD | Philips/Respironics | Merck & Co., Inc.; Jazz Pharmaceuticals; Vanda Pharmaceuticals; and Purdue Pharma LP |

None | None | 3/26/14 |

The NCCN Guidelines Staff have no conflicts to disclose.

NCCN Survivorship Panel Members

*,a,cCrystal S. Denlinger, MD/Chair†

Fox Chase Cancer Center

*,c,dJennifer A. Ligibel, MD/Vice Chair†

Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center

fMadhuri Are, MD£

Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center at The Nebraska Medical Center

b,eK. Scott Baker, MD, MS€ξ

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance

cWendy Demark-Wahnefried, PhD, RD≅

University of Alabama at Birmingham Comprehensive Cancer Center

b,dDebra L. Friedman, MD, MS€‡

Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center

*,gMindy Goldman, MDΩ

UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center

c,dLee Jones, PhDΠ

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

bAllison King, MD€Ψ‡

Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine

Grace H. Ku, MDξ‡

UC San Diego Moores Cancer Center

b,hElizabeth Kvale, MD£

University of Alabama at Birmingham Comprehensive Cancer Center

aTerry S. Langbaum, MAS¥

The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins

gKristin Leonardi-Warren, RN, ND#

University of Colorado Cancer Center

bMary S. McCabe, RN, BS, MS#

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

b,c,d,gMichelle Melisko, MD†

UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center

eJose G. Montoya, MDΦ

Stanford Cancer Institute

a,dKathi Mooney, RN, PhD#

Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah

c,eMary Ann Morgan, PhD, FNP-BC#

Moffitt Cancer Center

Javid J. Moslehi, MDλÞ

Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center

d,hTracey O’Connor, MD†

Roswell Park Cancer Institute

cLinda Overholser, MD, MPHÞ

University of Colorado Cancer Center

cElectra D. Paskett, PhDε

The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center - James Cancer Hospital and Solove Research Institute

f,hMuhammad Raza, MD‡

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital/The University of Tennessee Health Science Center

fKaren L. Syrjala, PhDθ

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance

*,fSusan G. Urba, MD†£

University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center

gMark T. Wakabayashi, MD, MPHΩ

City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center

*,hPhyllis Zee, MDΨΠ

Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University

NCCN Staff: Nicole McMillian, MS, and Deborah Freedman-Cass, PhD

KEY:

*Writing Committee Member

Subcommittees: aAnxiety and Depression; bCognitive Function; cExercise; dFatigue; eImmunizations and Infections; fPain; gSexual Function; hSleep Disorders

Specialties: ξBone Marrow Transplantation; λCardiology; εEpidemiology; ΠExercise/Physiology; ΩGynecology/Gynecologic Oncology; ‡Hematology/Hematology Oncology; ΦInfectious Diseases; ÞInternal Medicine; †Medical Oncology; ΨNeurology/Neuro-Oncology; #Nursing;; ≅Nutrition Science/Dietician; ¥Patient Advocacy; €Pediatric Oncology; θPsychiatry, Psychology, Including Health Behavior; £Supportive Care Including Palliative, Pain Management, Pastoral Care, and Oncology Social Work; ¶Surgery/Surgical Oncology; ωUrology

Footnotes

NCCN Categories of Evidence and Consensus

Category 1: Based upon high-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 2A: Based upon lower-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 2B: Based upon lower-level evidence, there is NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 3: Based upon any level of evidence, there is major NCCN disagreement that the intervention is appropriate.

All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise noted.

Clinical trials: NCCN believes that the best management for any cancer patient is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

Please Note

The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) are a statement of consensus of the authors regarding their views of currently accepted approaches to treatment. Any clinician seeking to apply or consult the NCCN Guidelines® is expected to use independent medical judgment in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine any patient’s care or treatment. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) makes no representation or warranties of any kind regarding their content, use, or application and disclaims any responsibility for their applications or use in any way. The full NCCN Guidelines for Survivorship are not printed in this issue of JNCCN but can be accessed online at NCCN.org.

Disclosures for the NCCN Survivorship Panel

At the beginning of each NCCN Guidelines panel meeting, panel members review all potential conflicts of interest. NCCN, in keeping with its commitment to public transparency, publishes these disclosures for panel members, staff, and NCCN itself.

Individual disclosures for the NCCN Survivorship Panel members can be found on page 500. (The most recent version of these guidelines and accompanying disclosures are available on the NCCN Web site at NCCN.org.)

These guidelines are also available on the Internet. For the latest update, visit NCCN.org.

References

- 1.Pachman DR, Barton DL, Swetz KM, Loprinzi CL. Troublesome symptoms in cancer survivors: fatigue, insomnia, neuropathy, and pain. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3687–3696. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paice JA, Ferrell B. The management of cancer pain. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:157–182. doi: 10.3322/caac.20112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raphael J, Hester J, Ahmedzai S, et al. Cancer pain: part 2: physical, interventional and complimentary therapies; management in the community; acute, treatment-related and complex cancer pain: a perspective from the British Pain Society endorsed by the UK Association of Palliative Medicine and the Royal College of General Practitioners. Pain Med. 2010;11:872–896. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, de Rijke JM, Kessels AG, et al. Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1437–1449. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meretoja TJ, Leidenius MH, Tasmuth T, et al. Pain at 12 months after surgery for breast cancer. JAMA. 2014;311:90–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun V, Borneman T, Piper B, et al. Barriers to pain assessment and management in cancer survivorship. J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2:65–71. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0047-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caraceni A, Weinstein SM. Classification of cancer pain syndromes. Oncology (Williston Park) 2001;15:1627–1640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hewitt DJ. The management of pain in the oncology patient. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2001;28:819–846. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(05)70238-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, et al. The Faces of Pain Scale-Revised: toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain. 2001;93:173–183. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Serlin RC, Mendoza TR, Nakamura Y, et al. When is cancer pain mild, moderate or severe? Grading pain severity by its interference with function. Pain. 1995;61:277–284. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00178-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soetenga D, Frank J, Pellino TA. Assessment of the validity and reliability of the University of Wisconsin Children’s Hospital Pain scale for Preverbal and Nonverbal Children. Pediatr Nurs. 1999;25:670–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ware LJ, Epps CD, Herr K, Packard A. Evaluation of the revised faces pain scale, verbal descriptor scale, numeric rating scale, and Iowa pain thermometer in older minority adults. Pain Manag Nurs. 2006;7:117–125. doi: 10.1016/j.pmn.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy MH, Chwistek M, Mehta RS. Management of chronic pain in cancer survivors. Cancer J. 2008;14:401–409. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31818f5aa7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moryl N, Coyle N, Essandoh S, Glare P. Chronic pain management in cancer survivors. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010;8:1104–1110. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crew KD, Greenlee H, Capodice J, et al. Prevalence of joint symptoms in postmenopausal women taking aromatase inhibitors for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3877–3883. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caraceni A, Zecca E, Bonezzi C, et al. Gabapentin for neuropathic cancer pain: a randomized controlled trial from the Gabapentin Cancer Pain Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2909–2917. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jongen JL, Huijsman ML, Jessurun J, et al. The evidence for pharmacologic treatment of neuropathic cancer pain: beneficial and adverse effects. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.10.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moore RA, Wiffen PJ, Derry S, McQuay HJ. Gabapentin for chronic neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011:CD007938. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007938.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koyyalagunta D, Bruera E, Solanki DR, et al. A systematic review of randomized trials on the effectiveness of opioids for cancer pain. Pain Physician. 2012;15:ES39–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akbik H, Butler SF, Budman SH, et al. Validation and clinical application of the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP) J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butler SF, Fernandez K, Benoit C, et al. Validation of the revised Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP-R) J Pain. 2008;9:360–372. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chou R, Fanciullo GJ, Fine PG, et al. Opioids for chronic noncancer pain: prediction and identification of aberrant drug-related behaviors: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society and American Academy of Pain Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Pain. 2009;10:131–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Passik SD, Kirsh KL. The interface between pain and drug abuse and the evolution of strategies to optimize pain management while minimizing drug abuse. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;16:400–404. doi: 10.1037/a0013634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Webster LR, Webster RM. Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the Opioid Risk Tool. Pain Med. 2005;6:432–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. [Accessed November 21, 2013];Transmucosal immediate release fentanyl (TIRF) risk evaluation and mitigation strateby (REMS) Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/ucm289730.pdf.

- 26.Bennett MI. Effectiveness of antiepileptic or antidepressant drugs when added to opioids for cancer pain: systematic review. Palliat Med. 2010 doi: 10.1177/0269216310378546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finnerup NB, Sindrup SH, Jensen TS. The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2010;150:573–581. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saarto T, Wiffen PJ. Antidepressants for neuropathic pain: a Cochrane review. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:1372–1373. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.144964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith EM, Pang H, Cirrincione C, et al. Effect of duloxetine on pain, function, and quality of life among patients with chemotherapy-induced painful peripheral neuropathy: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309:1359–1367. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baron R, Brunnmuller U, Brasser M, et al. Efficacy and safety of pregabalin in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy or postherpetic neuralgia: open-label, non-comparative, flexible-dose study. Eur J Pain. 2008;12:850–858. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johannessen Landmark C. Antiepileptic drugs in non-epilepsy disorders: relations between mechanisms of action and clinical efficacy. CNS Drugs. 2008;22:27–47. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200822010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leppert W, Buss T. The role of corticosteroids in the treatment of pain in cancer patients. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16:307–313. doi: 10.1007/s11916-012-0273-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mercadante SL, Berchovich M, Casuccio A, et al. A prospective randomized study of corticosteroids as adjuvant drugs to opioids in advanced cancer patients. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2007;24:13–19. doi: 10.1177/1049909106295431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wooldridge JE, Anderson CM, Perry MC. Corticosteroids in advanced cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2001;15:225–234. discussion 234-236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nabal M, Librada S, Redondo MJ, et al. The role of paracetamol and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in addition to WHO Step III opioids in the control of pain in advanced cancer: a systematic review of the literature. Palliat Med. 2012;26:305–312. doi: 10.1177/0269216311428528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richards BL, Whittle SL, Buchbinder R. Muscle relaxants for pain management in rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;1:CD008922. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008922.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richards BL, Whittle SL, van der Heijde DM, Buchbinder R. The efficacy and safety of muscle relaxants in inflammatory arthritis: a Cochrane systematic review. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2012;90:34–39. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.120340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cassileth BR, Keefe FJ. Integrative and behavioral approaches to the treatment of cancer-related neuropathic pain. Oncologist. 2010;15(Suppl 2):19–23. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-S504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang ST, Good M, Zauszniewski JA. The effectiveness of music in relieving pain in cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47:1354–1362. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwekkeboom KL, Cherwin CH, Lee JW, Wanta B. Mind-body treatments for the pain-fatigue-sleep disturbance symptom cluster in persons with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:126–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Montgomery GH, Weltz CR, Seltz M, Bovbjerg DH. Brief presurgery hypnosis reduces distress and pain in excisional breast biopsy patients. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2002;50:17–32. doi: 10.1080/00207140208410088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pfister DG, Cassileth BR, Deng GE, et al. Acupuncture for pain and dysfunction after neck dissection: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2565–2570. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stoelb BL, Molton IR, Jensen MP, Patterson DR. The efficacy of hypnotic analgesia in adults: a review of the literature. Contemp Hypn. 2009;26:24–39. doi: 10.1002/ch.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keefe FJ, Abernethy AP, Campbell LC. Psychological approaches to understanding and treating disease-related pain. Annu Rev Psychol. 2005;56:601–630. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheinfeld Gorin S, Krebs P, Badr H, et al. Meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions to reduce pain in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:539–547. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.0437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montgomery GH, Schnur JB, Kravits K. Hypnosis for cancer care: over 200 years young. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:31–44. doi: 10.3322/caac.21165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johannsen M, Farver I, Beck N, Zachariae R. The efficacy of psychosocial intervention for pain in breast cancer patients and survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138:675–690. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2503-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carvalho AP, Vital FM, Soares BG. Exercise interventions for shoulder dysfunction in patients treated for head and neck cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;4:CD008693. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008693.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mishra SI, Scherer RW, Geigle PM, et al. Exercise interventions on health-related quality of life for cancer survivors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD007566. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007566.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cantarero-Villanueva I, Fernandez-Lao C, Fernandez-de-Las-Penas C, et al. Effectiveness of water physical therapy on pain, pressure pain sensitivity, and myofascial trigger points in breast cancer survivors: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Pain Med. 2012;13:1509–1519. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fernandez-Lao C, Cantarero-Villanueva I, Fernandez-de-Las-Penas C, et al. Effectiveness of a multidimensional physical therapy program on pain, pressure hypersensitivity, and trigger points in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin J Pain. 2012;28:113–121. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318225dc02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McNeely ML, Parliament MB, Seikaly H, et al. Effect of exercise on upper extremity pain and dysfunction in head and neck cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2008;113:214–222. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rajotte EJ, Yi JC, Baker KS, et al. Community-based exercise program effectiveness and safety for cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:219–228. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0213-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Argoff CE. Topical analgesics in the management of acute and chronic pain. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88:195–205. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barros GA, Miot HA, Braz AM, et al. Topical (S)-ketamine for pain management of postherpetic neuralgia. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:504–505. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962012000300032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hempenstall K, Nurmikko TJ, Johnson RW, et al. Analgesic therapy in postherpetic neuralgia: a quantitative systematic review. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e164. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ho KY, Huh BK, White WD, et al. Topical amitriptyline versus lidocaine in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:51–55. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318156db26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin PL, Fan SZ, Huang CH, et al. Analgesic effect of lidocaine patch 5% in the treatment of acute herpes zoster: a double-blind and vehicle-controlled study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2008;33:320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.rapm.2007.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lynch ME, Clark AJ, Sawynok J, Sullivan MJ. Topical amitriptyline and ketamine in neuropathic pain syndromes: an open-label study. J Pain. 2005;6:644–649. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lynch ME, Clark AJ, Sawynok J, Sullivan MJ. Topical 2% amitriptyline and 1% ketamine in neuropathic pain syndromes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:140–146. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200507000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kopsky DJ, Hesselink JM. High doses of topical amitriptyline in neuropathic pain: two cases and literature review. Pain Pract. 2012;12:148–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2011.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fleming JA, O’Connor BD. Use of lidocaine patches for neuropathic pain in a comprehensive cancer centre. Pain Res Manag. 2009;14:381–388. doi: 10.1155/2009/723179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gammaitoni AR, Alvarez NA, Galer BS. Safety and tolerability of the lidocaine patch 5%, a targeted peripheral analgesic: a review of the literature. J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;43:111–117. doi: 10.1177/0091270002239817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brogan S, Junkins S. Interventional therapies for the management of cancer pain. J Support Oncol. 2010;8:52–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hurlow A, Bennett MI, Robb KA, et al. Transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS) for cancer pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;3:CD006276. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006276.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Choi TY, Lee MS, Kim TH, et al. Acupuncture for the treatment of cancer pain: a systematic review of randomised clinical trials. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1147–1158. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1432-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Garcia MK, McQuade J, Haddad R, et al. Systematic review of acupuncture in cancer care: a synthesis of the evidence. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:952–960. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]