Abstract

Cancer treatment, especially hormonal therapy and therapy directed toward the pelvis, can contribute to sexual problems, as can depression and anxiety, which are common in cancer survivors. Thus, sexual dysfunction is common in survivors and can cause increased distress and have a significant negative impact on quality of life. This section of the NCCN Guidelines for Survivorship provides screening, evaluation, and treatment recommendations for female sexual problems, including those related to sexual desire, arousal, orgasm, and pain.

Overview

Cancer treatment, especially hormonal therapy and therapy directed toward the pelvis, can often impair sexual function. In addition, depression and anxiety, which are common in survivors, can contribute to sexual problems. Thus, sexual dysfunction is common in survivors and can cause increased distress and have a significant negative impact on quality of life.1-5 Nonetheless, sexual function is often not discussed with survivors.6,7 Reasons for this include a lack of training of health care professionals, discomfort of providers with the topic, and insufficient time during visits for discussion.1 However, effective strategies for treating both female and male sexual dysfunction exist,8-11 making these discussions a critical part of survivorship care.

Female Aspects of Sexual Dysfunction

Female sexual problems relate to issues such as sexual desire, arousal, orgasm, and pain.12,13 Sexual dysfunction after cancer treatment is common in female survivors.4,14-20 A survey of 221 survivors of vaginal and cervical cancer found that the prevalence of sexual problems was significantly higher among survivors than among age- and race-matched controls from the National Health and Social Life Survey (mean number of problems 2.6 vs 1.1; P<.001).18 A survey of survivors of ovarian germ cell tumors and age-, race-, and education-matched controls found that survivors reported a significant decrease in sexual pleasure.21

Female sexual dysfunction varies with cancer site and treatment modalities.15,16 For example, survivors of cervical cancer who were treated with radiotherapy had worse sexual functioning scores (for arousal, lubrication, orgasm, pain, and satisfaction) than those treated with surgery, whose sexual functioning was similar to that of age- and race-matched noncancer controls.15 A recent systematic review of sexual functioning in cervical cancer survivors found similar results, except that no differences in orgasm/satisfaction were observed.22 In contrast, chemotherapy seems to be linked to female sexual dysfunction in breast cancer survivors,16 possibly related to the prevalence of chemotherapy-induced menopause in this population.13 In addition, survivors with a history of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) may have multiple types of sexual dysfunction, even after 5 to 10 years.23-25 Some of the sexual dysfunction associated with HSCT is related to graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), which can result in vaginal fibrosis, stenosis, mucosal changes, vaginal irritation, bleeding, and increased sensitivity of genital tissues.24,26 In addition, high-dose corticosteroids use for chronic GVHD can increase emotional lability and depression, affecting feelings of attractiveness, sexual activity, and quality of sexual life.

Evaluation and Assessment for Female Sexual Function

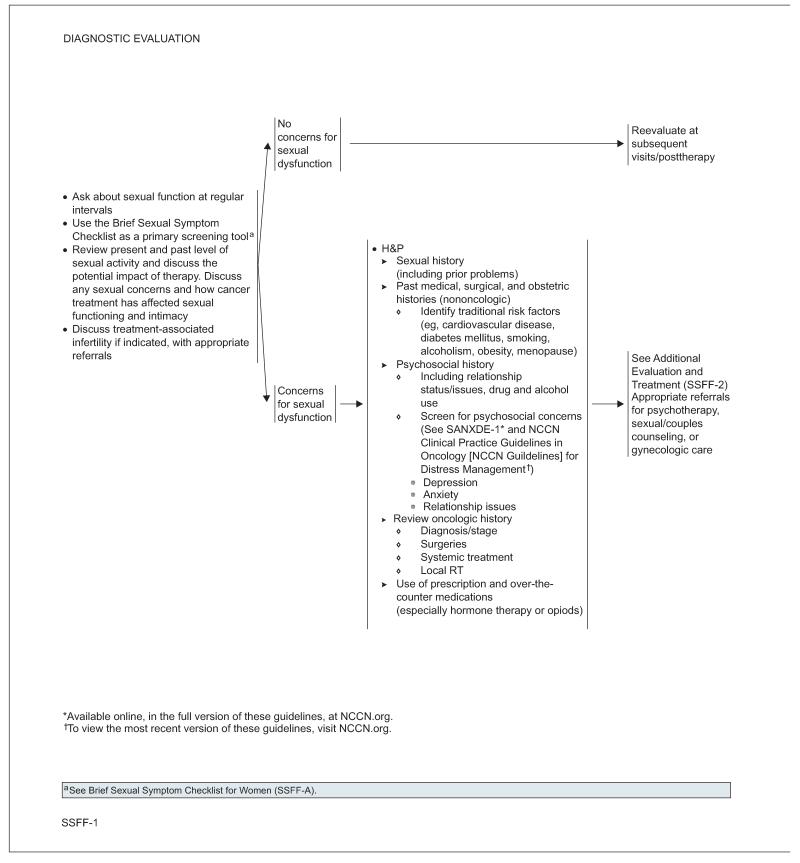

At regular intervals, female cancer survivors should be asked about their sexual function, including their sexual functioning before cancer treatment, their present activity, and how cancer treatment has impacted their sexual functioning and intimacy. The age and relationship status of the survivor may also affect sexual functioning (ie, some women may not be sexually active because of the physical health of their partner or quality of their relationship). The Brief Sexual Symptom Checklist for Women can be used as a primary screening tool.27 Inquiries into treatment-related infertility should be made if indicated, with referrals as appropriate.

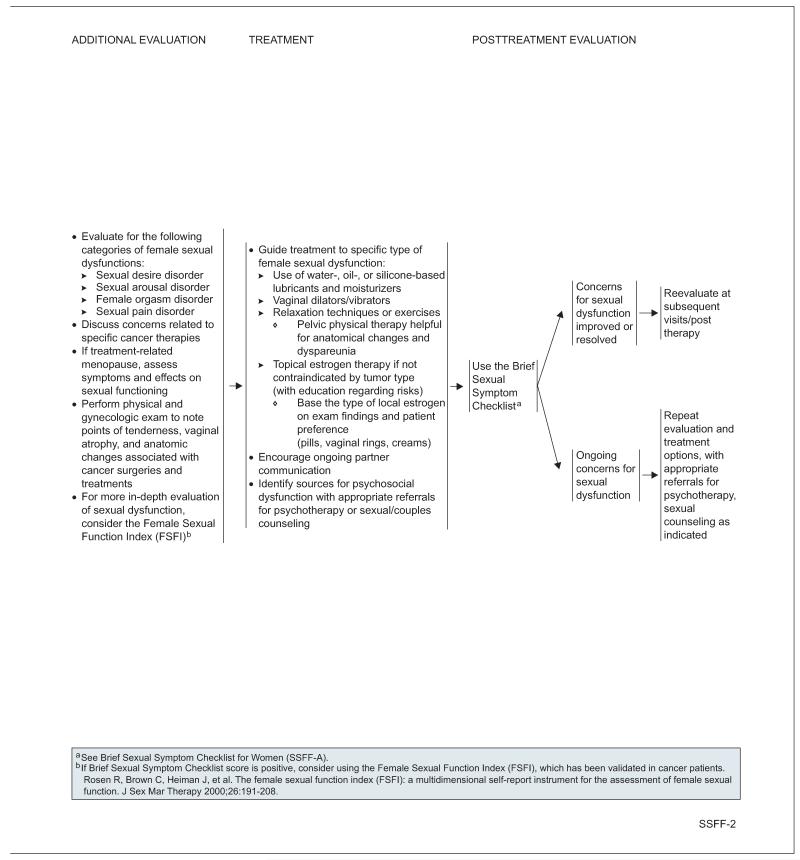

Patients with concerns about their sexual function should undergo a more thorough evaluation, including screening for possible symptoms and psychosocial problems (ie, anxiety, depression, relationship issues, drug or alcohol use) that can contribute to sexual dysfunction. It is also important to identify prescription and over-the-counter medications (especially hormone therapy, narcotics, and serotonin reuptake receptor inhibitors) that could be a contributing factor. Traditional risk factors for sexual dysfunction, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, smoking, and alcohol abuse, should also be assessed, as should the oncologic and treatment history. If anticancer treatments have resulted in menopause, menopausal symptoms and effects on sexual function should be assessed. Risks and benefits of hormone therapy should be considered in women who have not had hormone-sensitive cancers and who are prematurely postmenopausal. In addition, a physical and gynecologic examination should be performed to note points of tenderness, vaginal atrophy, and anatomic changes associated with cancer and cancer treatment.

For a more in-depth evaluation of sexual dysfunction, the Female Sexual Function Index can be considered.28 This instrument has been validated in patients with cancer and cancer survivors.29,30

Interventions for Female Sexual Dysfunction

Overall, the evidence base for interventions to treat female sexual dysfunction in survivors is weak, and high-quality studies are needed.31,32 Based on evidence from other populations, evidence from survivors when available, recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,12 and consensus among NCCN Survivorship Panel members, the panel made recommendations for treatment of female sexual dysfunction in survivors. The panel recommends that treatment be guided to the specific type of problem. The evidence base for each recommendation is described herein.

Water-, oil-, or silicone-based lubricants and moisturizers can help alleviate symptoms such as vaginal dryness and sexual pain.33 In one study of breast cancer survivors, the control group used a nonhormonal moisturizer and saw a transient improvement in vaginal symptoms.34

Pelvic floor muscle training may improve sexual pain, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and satisfaction. A small study of 34 survivors of gynecologic cancers found that pelvic floor training significantly improved sexual function.35

Vaginal dilators are recommended for vaginismus, sexual aversion disorder, vaginal scarring, or vaginal stenosis from pelvic surgery or radiation and associated with GVHD. However, evidence for the effectiveness of dilators is limited.36

Vaginal estrogen (pills, rings, or creams) has been shown to be effective in treating vaginal dryness, itching, discomfort, and painful intercourse in postmenopausal women.37-42 Small studies have looked at different formulations of local estrogen, but data assessing the safety of vaginal estrogen in survivors are limited.

Psychotherapy may be helpful for women experiencing sexual dysfunction, although evidence on efficacy is limited.43 Options include cognitive behavior therapy, for which some evidence of efficacy exists in survivors of breast, endometrial, and cervical cancer.44,45 Referrals for psychotherapy, sexual/couples counseling, or gynecologic care should be given as appropriate, and ongoing partner communication should be encouraged.46

Currently, the panel does not recommend the use of oral phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors (PDE5i) for female sexual dysfunction because of the lack of data regarding their effectiveness in women. Although thought to increase pelvic blood flow to the clitoris and vagina,47,48 PDE5i showed contradictory results in randomized clinical trials of various noncancer populations of women being treated for sexual arousal disorder.49-54 More research is needed before a recommendation can be made regarding the use of sildenafil for the treatment of female sexual dysfunction.

Clinical trials: NCCN believes that the best management of any cancer patient is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged. All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise indicated.

Version 1.2013, 03-08-13 ©2014 National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc. All rights reserved. The NCCN Guidelines® and this illustration may not be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of NCCN®.

Individual Disclosures for the NCCN Survivorship Panel.

| Panel Member | Clinical Research Support |

Advisory Boards, Speakers Bureau, Expert Witness, or Consultant |

Patent, Equity, or Royalty |

Other | Date Completed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Madhuri Are, MD | None | None | None | None | 5/15/13 |

| K. Scott Baker, MD, MS | None | None | None | None | 11/22/13 |

| Robert W. Carlson, MD | None | None | None | None | 12/9/13 |

| Elizabeth Davis, MD | None | None | None | None | 3/13/12 |

| Crystal S. Denlinger, MD | ImClone Systems Incorporated; MedImmune Inc.; and Merrimack Pharmaceuticals |

None | None | None | 6/21/13 |

| Stephen B. Edge, MD | None | None | None | None | 6/5/12 |

| Debra L. Friedman, MD, MS |

None | None | None | None | 5/26/13 |

| Mindy Goldman, MD | Pending | ||||

| Lee Jones, PhD | None | None | None | None | 2/2/12 |

| Allison King, MD | None | None | None | None | 8/12/13 |

| Elizabeth Kvale, MD | None | None | None | None | 10/7/13 |

| Terry S. Langbaum, MAS | None | None | None | None | 8/13/13 |

| Jennifer A. Ligibel, MD | None | None | None | None | 10/3/13 |

| Mary S. McCabe, RN, BS, MA |

None | None | None | None | 8/12/13 |

| Kevin T. McVary, MD | Allergan, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; NeoTract, Inc.; and National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases |

Allergan, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline; Eli Lilly and Company; and Watson Pharmaceuticals Inc. |

None | None | 6/7/13 |

| Michelle Melisko, MD | Celldex Therapeutics; and Galena Biopharma |

Agendia BV; Genentech, Inc.; and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation |

None | None | 10/11/13 |

| Jose G. Montoya, MD | None | None | None | None | 12/6/13 |

| Kathi Mooney, RN, PhD | University of Utah | None | None | None | 9/30/13 |

| Mary Ann Morgan, PhD, FNP-BC |

None | None | None | None | 8/19/13 |

| Tracey O’Connor, MD | None | None | None | None | 6/13/13 |

| Electra D. Paskett, PhD | Merck & Co., Inc. | None | None | None | 6/13/13 |

| Muhammad Raza, MD | None | None | None | None | 8/23/12 |

| Karen L. Syrjala, PhD | None | None | None | None | 10/3/13 |

| Susan G. Urba, MD | None | Eisai Inc.; and Helsinn Therapeutics (U.S.), Inc. |

None | None | 10/9/13 |

| Mark T. Wakabayashi, MD, MPH |

None | None | None | None | 6/19/13 |

| Phyllis Zee, MD | Philips/Respironics | Merck & Co., Inc.; Sanofi-Aventis Japan; UCB, Inc.; and Purdue Pharma L.P. |

None | None | 4/5/12 |

The NCCN Guidelines Staff have no conflicts to disclose.

NCCN Survivorship Panel Members

*,a,cCrystal S. Denlinger, MD/Chair†

Fox Chase Cancer Center

Robert W. Carlson, MD/Immediate Past Chair†

Stanford Cancer Institute

fMadhuri Are, MD£

Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center at The Nebraska Medical Center

b,eK. Scott Baker, MD, MS€ξ

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance

*,a,gElizabeth Davis, MDÞθ

Tewksbury Hospital

Stephen B. Edge, MD¶

Roswell Park Cancer Institute

b,dDebra L. Friedman, MD, MS€‡

Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center

*,gMindy Goldman, MDΩ

UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center

*,c,dLee Jones, PhDΠ

Duke Cancer Institute

bAllison King, MD€Ψ‡

Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine

*,b,hElizabeth Kvale, MD£

University of Alabama at Birmingham

Comprehensive Cancer Center

*,aTerry S. Langbaum, MAS¥

The Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center at Johns Hopkins

*,c,dJennifer A. Ligibel, MD†

Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women’s Cancer Center

*,bMary S. McCabe, RN, BS, MS#

Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

*,gKevin T. McVary, MDω

Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University

b,c,d,gMichelle Melisko, MD†

UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center

*,eJose G. Montoya, MDΦ

Stanford Cancer Institute

a,dKathi Mooney, RN, PhD#

Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah

*,c,eMary Ann Morgan, PhD, FNP-BC#

Moffitt Cancer Center

d,hTracey O’Connor, MD†

Roswell Park Cancer Institute

*,cElectra D. Paskett, PhDε

The Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center - James Cancer Hospital and Solove Research Institute

f,hMuhammad Raza, MD‡

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital/The University of Tennessee Health Science Center

*,fKaren L. Syrjala, PhDθ

Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center/Seattle Cancer Care Alliance

*,fSusan G. Urba, MD†£

University of Michigan Comprehensive Cancer Center

gMark T. Wakabayashi, MD, MPHΩ

City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center

*,hPhyllis Zee, MDΨΠ

Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University

NCCN Staff: Nicole McMillian, MS, and Deborah Freedman-Cass, PhD

KEY:

*Writing Committee Member

Subcommittees: aAnxiety and Depression; bCognitive Function; cExercise; dFatigue; eImmunizations and Infections; fPain; gSexual Function; hSleep Disorders

Specialties: ξBone Marrow Transplantation; εEpidemiology; ΠExercise/Physiology; ΩGynecology/Gynecologic Oncology; ‡Hematology/Hematology Oncology; ΦInfectious Diseases; ÞInternal Medicine; †Medical Oncology; ΨNeurology/Neuro-Oncology; #Nursing; ¥Patient Advocacy; €Pediatric Oncology; θPsychiatry, Psychology, Including Health Behavior; £Supportive Care Including Palliative, Pain Management, Pastoral Care, and Oncology Social Work; ¶Surgery/Surgical Oncology; ωUrology

Footnotes

NCCN Categories of Evidence and Consensus

Category 1: Based upon high-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 2A: Based upon lower-level evidence, there is uniform NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 2B: Based upon lower-level evidence, there is NCCN consensus that the intervention is appropriate.

Category 3: Based upon any level of evidence, there is major NCCN disagreement that the intervention is appropriate.

All recommendations are category 2A unless otherwise noted.

Clinical trials: NCCN believes that the best management for any cancer patient is in a clinical trial. Participation in clinical trials is especially encouraged.

Please Note

The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) are a statement of consensus of the authors regarding their views of currently accepted approaches to treatment. Any clinician seeking to apply or consult the NCCN Guidelines® is expected to use independent medical judgment in the context of individual clinical circumstances to determine any patient’s care or treatment. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN®) makes no representation or warranties of any kind regarding their content, use, or application and disclaims any responsibility for their applications or use in any way. The full NCCN Guidelines for Survivorship are not printed in this issue of JNCCN but can be accessed online at NCCN.org.

Disclosures for the NCCN Survivorship Panel

At the beginning of each NCCN Guidelines panel meeting, panel members review all potential conflicts of interest. NCCN, in keeping with its commitment to public transparency, publishes these disclosures for panel members, staff, and NCCN itself.

Individual disclosures for the NCCN Survivorship Panel members can be found on page 192. (The most recent version of these guidelines and accompanying disclosures are available on the NCCN Web site at NCCN.org.)

These guidelines are also available on the Internet. For the latest update, visit NCCN.org.

References

- 1.Bober SL, Varela VS. Sexuality in adult cancer survivors: challenges and intervention. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3712–3719. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donovan KA, Thompson LM, Hoffe SE. Sexual function in colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer Control. 2010;17:44–51. doi: 10.1177/107327481001700106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281:537–544. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morreale MK. The impact of cancer on sexual function. Adv Psychosom Med. 2011;31:72–82. doi: 10.1159/000328809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vomvas D, Iconomou G, Soubasi E, et al. Assessment of sexual function in patients with cancer undergoing radiotherapy—a single centre prospective study. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:657–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forbat L, White I, Marshall-Lucette S, Kelly D. Discussing the sexual consequences of treatment in radiotherapy and urology consultations with couples affected by prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2012;109:98–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White ID, Allan H, Faithfull S. Assessment of treatment-induced female sexual morbidity in oncology: is this a part of routine medical follow-up after radical pelvic radiotherapy? Br J Cancer. 2011;105:903–910. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fink HA, Mac Donald R, Rutks IR, et al. Sildenafil for male erectile dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1349–1360. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.12.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganz PA, Greendale GA, Petersen L, et al. Managing menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1054–1064. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.13.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nehra A. Erectile dysfunction and cardiovascular disease: efficacy and safety of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in men with both conditions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84:139–148. doi: 10.4065/84.2.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miles CL, Candy B, Jones L, et al. Interventions for sexual dysfunction following treatments for cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD005540. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005540.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 119: female sexual dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:996–1007. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821921ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilbert E, Ussher JM, Perz J. Sexuality after breast cancer: a review. Maturitas. 2010;66:397–407. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barni S, Mondin R. Sexual dysfunction in treated breast cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 1997;8:149–153. doi: 10.1023/a:1008298615272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frumovitz M, Sun CC, Schover LR, et al. Quality of life and sexual functioning in cervical cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7428–7436. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.00.3996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Belin TR, et al. Predictors of sexual health in women after a breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2371–2380. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.8.2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ganz PA, Rowland JH, Desmond K, et al. Life after breast cancer: understanding women’s health-related quality of life and sexual functioning. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:501–514. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.2.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindau ST, Gavrilova N, Anderson D. Sexual morbidity in very long term survivors of vaginal and cervical cancer: a comparison to national norms. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106:413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park SY, Bae DS, Nam JH, et al. Quality of life and sexual problems in disease-free survivors of cervical cancer compared with the general population. Cancer. 2007;110:2716–2725. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodrigues AC, Teixeira R, Teixeira T, et al. Impact of pelvic radiotherapy on female sexuality. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285:505–514. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-1988-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gershenson DM, Miller AM, Champion VL, et al. Reproductive and sexual function after platinum-based chemotherapy in long-term ovarian germ cell tumor survivors: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2792–2797. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.4590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lammerink EA, de Bock GH, Pras E, et al. Sexual functioning of cervical cancer survivors: a review with a female perspective. Maturitas. 2012;72:296–304. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Syrjala KL, Kurland BF, Abrams JR, et al. Sexual function changes during the 5 years after high-dose treatment and hematopoietic cell transplantation for malignancy, with case-matched controls at 5 years. Blood. 2008;111:989–996. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thygesen KH, Schjodt I, Jarden M. The impact of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation on sexuality: a systematic review of the literature. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:716–724. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watson M, Wheatley K, Harrison GA, et al. Severe adverse impact on sexual functioning and fertility of bone marrow transplantation, either allogeneic or autologous, compared with consolidation chemotherapy alone: analysis of the MRC AML 10 trial. Cancer. 1999;86:1231–1239. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991001)86:7<1231::aid-cncr18>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zantomio D, Grigg AP, MacGregor L, et al. Female genital tract graft-versus-host disease: incidence, risk factors and recommendations for management. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38:567–572. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hatzichristou D, Rosen RC, Derogatis LR, et al. Recommendations for the clinical evaluation of men and women with sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2010;7:337–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, et al. The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26:191–208. doi: 10.1080/009262300278597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baser RE, Li Y, Carter J. Psychometric validation of the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) in cancer survivors. Cancer. 2012;118:4606–4618. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jeffery DD, Tzeng JP, Keefe FJ, et al. Initial report of the cancer Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) sexual function committee: review of sexual function measures and domains used in oncology. Cancer. 2009;115:1142–1153. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flynn P, Kew F, Kisely SR. Interventions for psychosexual dysfunction in women treated for gynaecological malignancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD004708. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004708.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katz A. Interventions for sexuality after pelvic radiation therapy and gynecological cancer. Cancer J. 2009;15:45–47. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31819585cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sutton KS, Boyer SC, Goldfinger C, et al. To lube or not to lube: experiences and perceptions of lubricant use in women with and without dyspareunia. J Sex Med. 2012;9:240–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biglia N, Peano E, Sgandurra P, et al. Low-dose vaginal estrogens or vaginal moisturizer in breast cancer survivors with urogenital atrophy: a preliminary study. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010;26:404–412. doi: 10.3109/09513591003632258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang EJ, Lim JY, Rah UW, Kim YB. Effect of a pelvic floor muscle training program on gynecologic cancer survivors with pelvic floor dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:705–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miles T, Johnson N. Vaginal dilator therapy for women receiving pelvic radiotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD007291. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007291.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ayton RA, Darling GM, Murkies AL, et al. A comparative study of safety and efficacy of continuous low dose oestradiol released from a vaginal ring compared with conjugated equine oestrogen vaginal cream in the treatment of postmenopausal urogenital atrophy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103:351–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fooladi E, Davis SR. An update on the pharmacological management of female sexual dysfunction. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2012;13:2131–2142. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2012.725046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krychman ML. Vaginal estrogens for the treatment of dyspareunia. J Sex Med. 2011;8:666–674. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raghunandan C, Agrawal S, Dubey P, et al. A comparative study of the effects of local estrogen with or without local testosterone on vulvovaginal and sexual dysfunction in postmenopausal women. J Sex Med. 2010;7:1284–1290. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suckling J, Lethaby A, Kennedy R. Local oestrogen for vaginal atrophy in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD001500. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001500.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davison SL. Hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2012;24:215–220. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328355847e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brotto LA, Erskine Y, Carey M, et al. A brief mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral intervention improves sexual functioning versus wait-list control in women treated for gynecologic cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125:320–325. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duijts SF, van Beurden M, Oldenburg HS, et al. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and physical exercise in alleviating treatment-induced menopausal symptoms in patients with breast cancer: results of a randomized, controlled, multicenter trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4124–4133. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.41.8525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meana M, Jones S. Developments and trends in sex therapy. Adv Psychosom Med. 2011;31:57–71. doi: 10.1159/000328808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cavalcanti AL, Bagnoli VR, Fonseca AM, et al. Effect of sildenafil on clitoral blood flow and sexual response in postmenopausal women with orgasmic dysfunction. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;102:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang CC, Cao YY, Guan QY, et al. Influence of PDE5 inhibitor on MRI measurement of clitoral volume response in women with FSAD: a feasibility study of a potential technique for evaluating drug response. Int J Impot Res. 2008;20:105–110. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alexander MS, Rosen RC, Steinberg S, et al. Sildenafil in women with sexual arousal disorder following spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:273–279. doi: 10.1038/sc.2010.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Basson R, McInnes R, Smith MD, et al. Efficacy and safety of sildenafil citrate in women with sexual dysfunction associated with female sexual arousal disorder. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11:367–377. doi: 10.1089/152460902317586001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Basson R, Brotto LA. Sexual psychophysiology and effects of sildenafil citrate in oestrogenised women with acquired genital arousal disorder and impaired orgasm: a randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2003;110:1014–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Berman JR, Berman LA, Toler SM, et al. Safety and efficacy of sildenafil citrate for the treatment of female sexual arousal disorder: a double-blind, placebo controlled study. J Urol. 2003;170:2333–2338. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000090966.74607.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Caruso S, Intelisano G, Lupo L, Agnello C. Premenopausal women affected by sexual arousal disorder treated with sildenafil: a double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled study. BJOG. 2001;108:623–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Caruso S, Rugolo S, Agnello C, et al. Sildenafil improves sexual functioning in premenopausal women with type 1 diabetes who are affected by sexual arousal disorder: a double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:1496–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]