Abstract

BACKGROUND

Most research asks whether or not cohabitation has come to rival marriage. Little is known about the meaning of living apart together (LAT) relationships, and whether LAT is an alternative to marriage and cohabitation or a dating relationship.

OBJECTIVE

We examine across Europe: (1) the prevalence of LAT, (2) the reasons for LAT, and (3) the correlates of (a) LAT relationships vis-à-vis being single, married, or cohabiting, and (b) different types of LAT union.

METHODS

Using Generations and Gender Survey data from ten Western and Eastern European countries, we present descriptive statistics about LATs and estimate multinominal logistic regression models to assess the correlates of being in different types of LAT unions.

RESULTS

LAT relationships are uncommon, but they are more common in Western than Eastern Europe. Most people in LAT unions intend to live together but are apart for practical reasons. LAT is more common among young people, those enrolled in higher education, people with liberal attitudes, highly educated people, and those who have previously cohabited or been married. Older people and divorced or widowed persons are more likely to choose LAT to maintain independence. Surprisingly, attitudinal and educational differences are more pronounced in Eastern Europe than in Western Europe.

CONCLUSIONS

A tentative conclusion is that LAT is more often a stage in the union formation process than an alternative to marriage and cohabitation. Yet some groups do view LAT as substituting for marriage and cohabitation, and these groups differ between East and West. In Eastern Europe a cultural, highly educated elite seems to be the first to resist traditional marriage norms and embrace LAT (and cohabitation) as alternative living arrangements, whereas this is less the case in Western Europe. In Western Europe, LAT unions are mainly an alternative for persons who have been married before or had children in a prior relationship.

1. Introduction

The ways in which people structure their intimate relationships diversified across developed societies throughout the latter part of the 20th century. During most of the 20th century, marriage was the dominant relationship type. Since the 1970s, unmarried cohabitation has become more prevalent (Bumpass and Lu 2000; Kiernan 2004). In more recent years, increased attention also has been paid to people who have someone whom they consider to be an intimate partner, but who is not living with them – so-called LAT relationships (Strohm et al. 2009). Whether or not individuals choose this as a conscious, long-term strategy is the subject of increasing debate (De Jong Gierveld 2008; Duncan et al. 2013; Levin and Trost 1999; Roseneil 2006).

As yet, little is known about the prevalence of LAT relationships across developed societies, about the reasons why people opt for this arrangement, and about the characteristics of those in LAT unions. This paper aims to provide insight into the phenomenon of LAT unions for a range of European countries by addressing three questions:

How prevalent is having an intimate partner outside the household across a range of European countries?

Why do people opt for this living arrangement? Are there different types of LAT relationship by country?

What socioeconomic, demographic, and attitudinal characteristics are associated with whether or not an individual is in a LAT relationship, and how do those who are in LAT unions differ from those who are single, married, or in a cohabiting union? Do people in different types of LAT union differ with respect to these background characteristics?

Contrary to most previous studies (e.g., Castro-Martín, Domínguez-Folguers, and Martín-García 2008; Régnier-Lollier, Beaujouan, and Villeneuve-Gokalp 2009), we not only compare people in LAT relationships with people in co-residential unions, but also with singles (also see Strohm et al. 2009). A comparison of the profile of people in LAT unions with that of singles on the one hand and that of married and cohabiting people on the other hand may show whether LAT is an alternative to singlehood or an alternative to co-residential unions (Rindfuss and VandenHeuvel 1990).

We use cross-sectional data from the Generations and Gender Survey (GGS), a survey conducted in a large number of European and other developed countries (United Nations 2005; Vikat et al. 2007). The GGS offers a unique opportunity to examine cross-national differences in intimate relationships and covers both Western and Eastern European countries.

2. Background and hypotheses

2.1 The meaning of LAT relationships

Little is known about the meaning of LAT relationships in relation to other union statuses such as marriage, cohabitation, and singlehood. Most theories have focused on the choice between cohabitation and marriage, and thereby on the meaning of cohabitation (e.g., Bianchi and Casper 2000; Heuveline and Timberlake 2004; Klijzing 1992; Rindfuss and VandenHeuvel 1990). This literature sees cohabitation as an alternative to marriage, a normative stage in the marriage process, a trial marriage, or an alternative to singlehood. Studies of LAT relationships are more recent due, in part, to limited data on these unions (e.g., De Jong Gierveld 2004, 2008; Duncan et al. 2013; Evertsson and Nyman 2013; Haskey and Lewis 2006; Levin 2004; Régnier-Lollier, Beaujouan, and Villeneuve-Gokalp 2009; Roseneil 2006; Strohm et al. 2009).

The emerging literature on LAT suggests multiple reasons why people opt for LAT. Roseneil (2006) distinguishes those who are “gladly” apart, those who are “regretfully” apart, and those who are “undecided” about whether or not to live apart. Those gladly apart prefer not to live together, whereas those who are regretfully apart would prefer to live together but are living apart due to constraints, such as not being able to find affordable housing. More recently, Duncan et al. (2013) identify two dimensions that distinguish types of LAT union. The first is whether the members of the couple prefer to live apart or have to live apart because of situational constraints, much like Roseneil's distinction between “gladly” and “regretfully”. The second dimension is whether people conceive of LAT as a stage leading up to cohabitation or as a (semi-)permanent state. Empirically, Duncan et al. (2013) use British data to distinguish four types of LAT union, within the space defined by the cross-classification of these dimensions. Most individuals in LAT relationships think it is too soon for them to live together or are living apart due to practical constraints.

The distinction between LAT as a state or a stage in the union formation process mimics the earlier discussion on cohabitation (Hiekel, Liefbroer, and Poortman 2014). On the one hand, LAT unions can be viewed as an alternative to co-residential relationship types, having emerged as a new type of relationship that may substitute for marriage and cohabitation and fit within the process of the Second Demographic Transition. During this transition, values of individualism and autonomy increasingly permeate the culture of modern societies (Lesthaeghe 2010). Because LAT relationships leave more room for independence and autonomy because partners spend more time in separate pursuits than those in co-residential relationships, LAT relationships may be an indication of a more advanced stage in the Second Demographic Transition (Levin 2004). Alternatively, a preference for LAT unions may be based on practical considerations rather than on ideological ones. LAT unions may be a response to social welfare program requirements, such as rules about the receipt of individual unemployment or pension benefits, or problems associated with housing shortages or geographically disparate employment opportunities. Parents also may prefer a LAT union if they are concerned about limiting a new partner's involvement with their children.

On the other hand, LAT unions can be viewed as a stage in the process of union formation (e.g., Castro-Martín, Domínguez-Folguers, and Martín-García 2008). Parallel to the ideal-type distinctions made about the meaning of cohabitation, LAT unions may be an element in the search for a co-residential partner. If LAT unions are part of the courtship process in which partners assess their compatibility they may be an alternative to singlehood, much as Rindfuss and Vandenheuvel (1990) suggest is true for cohabitation. LAT relationships also may be unions in which the partners already know they are compatible and plan to marry or cohabit as soon as practical circumstances allow.

Although the distinction between state and stage is important for theoretical reasons, it may be difficult for individuals to classify their own LAT relationship this way. The difficulty may be greater if people have practical reasons for being in a LAT relationship. Practical reasons may be temporary (e.g., because partners cannot yet find suitable housing or have jobs that are far apart) or more permanent (e.g., the wish not to upset children from a previous relationship). We distinguish different types of LAT relationship according to the main reasons that people provide: (i) independence, (ii) practical reasons, or (iii) not being ready to commit yet. Because of the ambiguity of practical reasons being considered as temporary constraints preventing a couple from living together (in line with the view of LAT as a stage) or as a more permanent reason for wanting to live apart (in line with the view of LAT as a state), we make no further distinction between those mentioning practical reasons for living apart.

2.2 Individual variation in who is in a LAT relationship

Individuals' attitudes and values, their stage in life, and their socioeconomic resources influence the types of unions they form and maintain. We consider how these dimensions of variation are associated with individuals' union status (single, in LAT union, cohabiting, married) as well as how these characteristics are associated with the types of LAT relationship or reasons for being in a LAT relationship.

2.2.1 Attitudes

If living in a LAT relationship is a deliberate choice for reasons of autonomy and independence, it is likely that people with liberal and progressive values are more likely to opt for LAT relationships than for co-residential partnerships. Previous studies find little or no difference in the individualistic orientations of those in LAT unions compared to those in other types of union (Strohm et al. 2009; Duncan and Phillips 2010). For other measures, such as gender role attitudes, family attitudes, or religiosity, evidence is mixed, suggesting that people in a LAT relationship are not a cultural elite or among the first to adopt LAT relationships as a new family form, as the Second Demographic Transition theory would predict (Castro-Martín, Domínguez-Folguers, and Martín-García 2008; De Jong Gierveld 2004; Duncan and Phillips 2010; Strohm et al. 2009). Whether those who hold more liberal attitudes are more likely to be single than in a LAT partnership is unclear. Remaining single may be the ultimate choice for those who seek autonomy and independence. Singlehood, however, also may result from constraints, including the lack of potential partners, and evidence suggests this to be more common than singlehood as a choice (Poortman and Liefbroer 2010). Thus, if people see LAT as a choice for a less committed, more individualized relationship, we hypothesize:

H1a: People with liberal attitudes are more likely to be in a LAT relationship compared to being married or cohabiting than people with less liberal attitudes. It is unclear a priori how liberal attitudes are associated with being in a LAT relationship compared to being single.

As implied by this discussion, attitudes may be linked to the reasons individuals opt for a LAT relationship. Liberal attitudes are more likely to be associated with being in a LAT relationship that individuals describe as a choice for independence than as a choice for practical reasons or because they are not ready to live together or marry. Thus, we hypothesize:

H1b: Compared to those with less liberal attitudes, people with more liberal attitudes are more likely to be in a LAT relationship because of independence compared to the other types of LAT.

2.2.2 Previous unions and parenthood

Individuals may choose LAT unions as a result of their previous experiences with marriage and parenthood (De Jong Gierveld 2004; Régnier-Lollier, Beaujouan, and Villeneuve-Gokalp 2009). Those with children from previous relationships, the divorced, and the widowed may prefer LAT over marriage or cohabitation because they are reluctant to risk a repeat of the loss and pain they have experienced (De Jong Gierveld 2002; Poortman 2007). The divorced, in particular, may want to avoid making the same mistakes they made in their marriage (Levin 2004: 233). They may prefer to go slowly in the relationship and choose to live apart. Older widowed women emphasize wanting to keep their autonomy and staying in their familiar family homes as reasons for having a LAT relationship (De Jong Gierveld 2002; Pyke 1994).

Practical reasons may also prevent the divorced, the widowed, and those with children from a previous relationship from forming a co-residential union (De Jong Gierveld 2002). The fear of losing alimony or the pension of the deceased partner, or the protection of financial resources for the sake of children from a previous relationship may be reasons to avoid a co-residential relationship for those who are divorced, widowed, or single parents (ibid). Evidence from past research is consistent with this reasoning. Those who have been divorced or widowed are more likely to be in a LAT union than those who have not experienced marital dissolution (De Jong Gierveld and Latten 2008; Régnier-Lollier, Beaujouan, and Villeneuve-Gokalp 2009). LAT unions may also enable individuals to balance their interests with the needs of their children (Levin 2004). For example, children may find it difficult that their mother or father has a new partner after divorce or bereavement, in particular when the new partner comes to live in the old family home (De Jong Gierveld 2002, 2004). It is unclear how previous union experiences affect the chances of having a LAT relationship vis-à-vis being single, because singlehood may be either a choice or the result of disadvantages in the marriage market where previous relationships might be a liability (De Graaf and Kalmijn 2003; Poortman 2007; South 1991).

H2a: Those who have been divorced, widowed, or who have children from previous relationships are more likely to be in a LAT relationship compared to married or cohabiting than people without such life-course experiences. It is unclear a priori how these previous experiences are associated with being in a LAT union compared to being single.

Following this line of reasoning, we also expect prior relationships to be associated with the reasons for being in a LAT relationship.

H2b: Divorced people, widowed people, and persons with children from previous relationships are more likely to be in a LAT because of independence or for practical reasons compared to being in a LAT because they are not ready to live together than people without such life-course experiences.

2.2.3 Socioeconomic characteristics

Economic constraints may increase the likelihood that a couple forms a LAT union instead of a co-residential partnership. Although living together has financial advantages because of economies of scale (Becker 1981), marriage, and to a lesser extent cohabitation, also have start-up costs. Even without the cost of a wedding, partners may need to buy or rent a new house and new furniture. In addition, the cultural requirement that couples should be economically secure before they marry (Oppenheimer 1988) may increase LAT unions among those who cannot yet afford to marry. Compared to those who are unemployed, employed persons are less likely to be in a LAT relationship than in a co-residential union (Régnier-Lollier, Beaujouan, and Villeneuve-Gokalp 2009). Similarly, the male partner's work instability increases the chances of being in a LAT relationship (Castro-Martín, Domínguez-Folguers, and Martín-García 2008).

Although a LAT relationship has few financial advantages compared to being single, economic considerations may still play a role in whether or not an individual is in a LAT relationship compared to being single. To the extent that LAT unions are part of the partnership search process, socioeconomic resources may increase the chance of being in a LAT relationship compared to being single.

H3a: Individuals' socioeconomic resources are negatively associated with being in a LAT relationship compared to being married or cohabiting. Economic resources, however, are likely to increase the likelihood of being in a LAT union compared to being single.

As a corollary, the financial constraints that foster LAT unions over co-residential union also suggest that:

H3b. Individuals with few socioeconomic resources are more likely to be in LAT unions for practical reasons rather than other reasons than those with many resources.

2.2.4 Individual developmental change or life stage

Age-related processes of developmental change (Clausen 1991) also may be associated with whether individuals remain single or form a non-co-residential partnership or a co-residential partnership. Major transitions in life, such as leaving the parental home, getting married, and having children, are typically made at certain ages, in part because of norms and institutional structures that are age-graded (Liefbroer and Billari 2010; Settersten and Hagestad 1996). Early and young adulthood are periods in which people experiment, including with different partners, whereas most people have settled down by their early thirties (Arnett 2000). Age-graded institutions, such as colleges, also may limit individuals' ability to form co-residential partnerships (vs. LAT unions or singlehood) if they are living with their parents to afford schooling or are attending college in different cities (Régnier-Lollier, Beaujouan, and Villeneuve-Gokalp 2009). Higher Education enrollment is normatively inconsistent with starting a family (Blossfeld and Huinink 1991). Previous studies find that LAT relationships are more common than co-residential unions among young adults than among those who are older (Duncan and Phillips 2010; Haskey 2005; Haskey and Lewis 2006; Strohm et al. 2009). We hypothesize that:

H4a. Young persons are more likely to be in LAT unions (vs. cohabiting or marital unions) than older persons. They are also more likely to be single compared to being in any type of relationship.

H4b: Higher Education enrollment is positively associated with being in a LAT relationship compared to being married or cohabiting. It is unclear whether people enrolled in higher education are more or less likely to be in a LAT relationship than being single.

Given that young adulthood constitutes a life phase in which people are still developing their identity, are open to experimentation, and are confronted with changes in many life domains (Arnett, 2000), it is likely that young people's LAT relationships are often still quite provisional, and may resemble dating relationships. Therefore, we also hypothesize that:

H4c: Younger people are more likely to be in a LAT union because they are not ready yet (vs. other types of LAT), compared to older people.

H4d: Compared to those not enrolled in higher education, those who are enrolled are more likely to be in a LAT union because they are not ready yet versus the other types of LAT.

2.3 Cross-national differences in LAT relationships

Cross-national information on the prevalence of LAT relationships and on the relative importance of the different types of LAT relationships is scarce. Yet countries are likely to differ in the prevalence of LAT relationships and the types of LAT relationship, for many of the same reasons that countries vary in rates and prevalence of co-residential relationships. Cultural, economic, and institutional differences across nations contribute to differences in living arrangements and the meanings attached to them. A first step toward understanding these variations is to provide a more complete description of cross-national differences for an extensive set of Eastern and Western European countries than has been possible to date.

We focus on potential differences in the prevalence and precursors of LAT unions in Eastern and Western Europe. In cultural terms, countries in Western Europe have progressed further in the process of the Second Demographic Transition than Eastern European countries (Fokkema and Liefbroer 2008; Sobotka 2008) and therefore are likely to have a cultural climate that is more accepting of non-traditional family forms such as LAT or cohabitation (Kiernan 2001; Levin 2004). When LAT relationships are more accepted an increasing number of people will opt for LAT and a larger proportion of LAT relationships will be motivated by considerations of autonomy and privacy.

Economic differences between Western and Eastern European countries also could explain cross-national variation in the prevalence and precursors of LAT. In countries with a large housing shortage, people could be constrained from having a LAT relationship for a considerable period of time. Housing shortages are more likely in Eastern European countries than in Western European countries. On the other hand, Eastern European countries have a long tradition of dealing with such shortages by having the partner of a child moving in with the parents (Fokkema and Liefbroer 2008). Thus it is unclear whether the housing market leads to a higher or lower prevalence of LAT relationships in Eastern Europe. A country's level of wealth may contribute to the prevalence of LAT unions as well, because wealth increases a couple's ability to accumulate the financial means needed to start a joint household. Thus less prosperous countries such as those in Eastern Europe may have a higher prevalence of LAT unions formed for practical reasons.

Finally, differences between Eastern and Western Europe in the prevalence of LAT unions could result from institutional differences between these parts of Europe. For instance, in welfare regimes where the state provides ample support for individuals to live independently, LAT unions are expected to be more prevalent. Unfortunately our data do not allow us to perform a fully-fledged institutional comparison across a broad range of welfare regimes. We lack data on countries in Southern and Northern Europe, the UK, and Ireland. The Western European countries in our data all belong to the conservative welfare regime type (Esping-Andersen 1990). There is no generally agreed upon typology of welfare types in Eastern Europe, but Fenger (2007) suggests that two types can be distinguished, one consisting of the countries of the former USSR and one consisting of other Eastern European post-communist countries. Both types, however, are characterized by a lower level of decommodification than in conservative countries, thus suggesting – if anything – that support for living independently might be larger in the Western European countries in our dataset than in the Eastern European countries.

These cultural, economic, and institutional differences between Western and Eastern European countries suggest the following hypotheses:

H5a. People in Western Europe are more likely than people in Eastern Europe to be in a LAT union because they value independence, whereas people in Eastern Europe are more likely than people in Western Europe to be in a LAT union for practical reasons.

H5b: Attitudes are expected to be stronger predictors of union status among people in Western Europe than among people in Eastern Europe. Economic factors are expected to be stronger predictors of union status in Eastern Europe than in Western Europe.

3. Methods

3.1 Data

We use data from the first wave of the Generations and Gender Survey, a comparative set of panel surveys conducted in many European and other developed countries (United Nations 2005; Vikat et al. 2007). The current analyses use harmonized data from ten countries – Norway, Belgium, France, Germany, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Lithuania, Russia, and Georgia – that have information on whether respondents are in a LAT union and on union intentions. Information on reasons for being in a LAT union is available for all of these countries except Norway and Hungary. Data were collected between 2004 and 2010. An advantage of the GGS is its large sample size and its coverage of a broad age-range of 18 to 79 years, allowing us to study the prevalence of different types of LAT relationship across the age spectrum. The number of respondents across countries varies between 7,149 in Belgium and 14,827 in Norway. Data for all countries were weighted to adjust for unequal probabilities of sample selection and nonresponse differences within countries (see www.ggp-i.org for more information).

3.2 Measurement

3.2.1 Dependent variables

Partner status

All respondents who indicated that they did not have a partner in the household were asked whether they currently had “an intimate relationship with someone they were not living with”. They were explicitly reminded that this could also be their spouse or a partner in a same-sex relationship. We combine these responses with reports on marital status and cohabitation to distinguish four union statuses: single, cohabiting, married, and LAT. The percentage of respondents in a LAT union who were formally married was low (around 5%) in all countries expect Russia (12%) and Georgia (48%). In our analysis these respondents are classified as being in a LAT union.

Union-formation intentions

Every respondent who had a partner outside the household was asked “Do you intend to start living with your partner during the next three years?” Response categories were “definitely not”, “probably not”, “probably yes”, and “definitely yes”. We contrast those who answered probably or definitely yes to those who gave other answers.

Types of LAT relationship

Respondents who indicated that they had a partner with whom they were not sharing a household were asked “Are you living apart because you and/or your partner want to or because circumstances prevent you from living together?” The answer categories were “I want to live apart”, “Both my partner and I want to live apart”, “My partner wants to live apart”, and “We are constrained by circumstances”. In addition, the survey obtained the main reason that partners wanted to live apart (i.e., financial reasons, to keep independence, because of children, not yet ready for living together, other) or the main constraining circumstances (i.e., work circumstances, financial circumstances, housing circumstances, legal circumstances, my partner has another family, other).

We used answers to these questions to distinguish five types of LAT relationship. In a first step, respondents who answered that they were constrained by circumstances were classified as “LAT – practical constraints”. Next, among the remaining respondents, those who stated that they and/or their partner wanted to live apart and wanted to do so because of practical advantages, such as financial reasons and because of children, were classified as “LAT – practical advantages”. Next, among the remaining respondents, those who indicated that either they or their partner wanted to live apart for reasons of autonomy were classified as “LAT – independence”. Finally, respondents who felt that either they or their partner were not ready to start living together were classified as “LAT – not ready yet”. In our discussion in Section 5 we consider the difficulty respondents faced in distinguishing between the types of practical reason.

Most respondents in LATs said that they and their partner agreed about whether or not they wanted to be in a LAT union. Only between 1.3% (Belgium) and 5.2% (Russia) of respondents in LAT unions said that they did not want to live apart but that their partner did. These respondents were classified based on the reason given for their partner's preference for LAT. Among respondents who said that both they and their partner wanted to live apart, 17.9% differed in their reasons for being in a LAT relationship. If it was reported that one of the partners wanted to live apart for practical reasons (financial reasons, because of children), the LAT union was classified as “LAT – practical advantages”. If neither mentioned practical advantages but one of them mentioned an ideological reason (to maintain independence) the LAT union was classified as “LAT – independence”. Finally, a small residual group of respondents whose main reason for LAT was unclear were classified as “LAT – other”.

3.2.2 Independent variables

Attitudes

We include three measures of attitude. All attitude items used a five-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. “Religiousness” is the sum of respondents' responses to three questions, on the importance of baptism, having a religious wedding, and having a religious funeral. For example, the baptism question is: “It is important for an infant to be registered in the appropriate religious ceremony?” In all countries, the three items form a reliable scale with Cronbach's α ranging from 0.79 in Russia to 0.90 in Germany. A higher-scale score indicates a stronger commitment to institutionalized religion.

Conservative opinions about marriage are measured by responses to the statement, “Marriage is an outdated institution”. A higher score indicates the respondent disagrees, that is, holds a more favorable view of marriage.

Support for gender equality is indicated by agreement with: “Looking after the home or family is just as fulfilling as working for pay”. This item was reversed-coded. A higher score is interpreted as indicating a stronger preference for gender equality.

Previous unions and parenthood

We use a dummy variable to indicate whether or not respondents had ever experienced a marital divorce or separation from a cohabiting partner, or the death of a partner. Another dummy variable indicates whether or not a respondent had any children from a previous relationship.

Socioeconomic indicators

We include several measures of socioeconomic status. Individuals' subjective evaluation of household income is measured by responses to the question: “Thinking of your household's total monthly income, is your household able to make ends meet?” Answer categories ranged from 1 to 6, anchored by “with great difficulty” and “very easily”. We use a subjective evaluation of household income instead of an objective measure because of the large income differences among the countries in the analysis. The second indicator we focus on is a dichotomous indicator distinguishing respondents who were employed from those who were not.

We also consider the highest level of education completed successfully. Answers were coded according to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED), although some countries used a slightly different country-specific coding scheme. Respondents were categorized into three groups. Those with ISCED codes 0 through 2 (lower secondary education or less) were classified as “low education”; those with ISCED codes 3 or 4 (higher secondary education) were classified as “medium education”; and those with ISCED codes 5 or 6 (tertiary education) were classified as “high education”.

Developmental change

We measure developmental variation by age, and distinguish those aged 35 and under from those aged 36 and over.4 It is important to notice that with cross-sectional data it is impossible to disentangle age and cohort effects. In addition to age, we constructed a dichotomous variable to identify respondents who were enrolled in higher education.

Table 1 shows descriptive information on all the independent variables, broken down by union status.

Table 1.

Descriptive information (Mean scores and %) on independent variables, by union status

| Single | Married | Cohabiting | LAT | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious importance | 3.9 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.9 |

| Traditional marriage attitude | 3.6 | 4.0 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.8 |

| Gender equality | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Experienced union dissolution | 53% | 11% | 40% | 43% | 28% |

| Had children from former relationship | 19% | 5% | 19% | 22% | 11% |

| Subjective income | 2.9 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.2 |

| Employed | 41% | 59% | 71% | 63% | 55% |

| Low education | 29% | 22% | 21% | 15% | 24% |

| Middle education | 51% | 52% | 51% | 45% | 51% |

| High education | 20% | 26% | 28% | 30% | 25% |

| Aged 36 and over | 46% | 46% | 16% | 18% | 42% |

| Enrolled in higher education | 13% | 2% | 7% | 22% | 7% |

| Male | 39% | 49% | 48% | 49% | 46% |

Note: Mean scores on independent variables are presented, unless indicated otherwise

3.3 Analysis strategy

First, descriptive information on the prevalence of LAT relationships and the distribution across different types of LAT relationship are presented. We present information on the prevalence of LAT relationships and on union formation intentions for ten countries, and information on types of LAT relationship for the eight countries that collected data on this aspect of LAT.

Second, a multinomial logistic regression analysis is performed with type of union status (single, LAT, cohabiting, married) as the dependent variable, and the selected indicators of correlates and precursors as independent variables. In our results tables the relative risk ratios for each of these indicators are shown comparing LAT unions to each of the other three union types. Wald tests are performed to test whether the overall effect of specific covariates across union status is statistically significant. Only if the Wald test is statistically significant are differences between specific union types assessed. To illustrate what these effects imply in substantive terms – based on these parameter estimates – predicted probabilities of being in each of the union status categories are calculated for key variables, with values of all other variables set at the mean. In addition to a pooled analysis we also performed separate analyses for Western and Eastern European countries, and a pooled model with all background variables and interactions with European region. Because many background variables showed different patterns in Eastern and Western European countries we also present results separately for these two regions.

Third, we performed another multinomial logistic regression analysis in which different types of LAT union are compared. Because of the small number of observations in the “LAT – practical advantages” category, this category is combined with the “LAT – practical constraints” category. Preliminary analyses (results not shown) show that the factors influencing these two practical categories are generally similar. Again, Wald tests are performed to test whether the overall effect of specific covariates across union type is statistically significant. In addition the predicted probabilities of being in each type of LAT relationship based on these multinomial logistic regression models are calculated to illustrate the size of the effects for some key variables of interest. We also perform separate analyses for Western and Eastern European countries. Very few West-East differences in parameter estimates are observed for the analysis of type of LAT union, so we do not present results separately for Eastern and Western countries.

4. Results

4.1 Descriptive analyses

The top panel of Table 2 gives an overview of the prevalence of LAT unions in the ten countries in our study. In all countries, less than 10% of the population aged 18 to 79 is in a LAT relationship. It is the least common union status in every country. The percentage is close to ten, though, in all Western European countries (Belgium, Germany, France, and Norway) and in Russia. The percentage is around or below five in all other countries, with Georgia having by far the lowest percentage of respondents reporting that they are in a LAT relationship at only 1.5% of respondents.

Table 2.

Percentage distribution of adults’ union statuses, percentage of adults in LATs who intend to live together, and LAT type, by country

| Romania | Russia | Georgia | Bulgaria | Lithuania | Belgium | Germany | France | Norway | Hungary | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Union Status | ||||||||||

| LAT | 4.2 | 8.6 | 1.5 | 4.8 | 5.2 | 9.5 | 8.6 | 8.8 | 9.6 | 4.4 |

| Single | 24.3 | 25.4 | 34.4 | 28.4 | 38.8 | 22.0 | 25.9 | 24.1 | 24.4 | 31.4 |

| Married | 67.3 | 56.5 | 54.7 | 60.3 | 49.2 | 55.6 | 56.9 | 52.6 | 50.4 | 55.0 |

| Cohabiting | 4.3 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 6.6 | 6.8 | 12.9 | 8.6 | 14.6 | 15.5 | 9.3 |

| LAT Intentions | ||||||||||

| LATs who intend to live together (vs. not) | 78.9 | 55.3 | 65.5 | 67.7 | 57.0 | 67.2 | 67.9 | 75.6 | 65.3 | 68.0 |

| LAT Reasons | ||||||||||

| LAT - Not ready yet | 25.0 | 10.4 | 6.4 | 21.2 | 23.1 | 13.9 | 17.6 | 10.5 | ||

| LAT - Independence | 12.7 | 11.6 | 8.3 | 15.1 | 15.2 | 13.5 | 23.3 | 16.9 | ||

| LAT - Practical advantages | 6.6 | 2.9 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 6.8 | 6.1 | 3.0 | 3.9 | ||

| LAT - Practical constraints | 50.9 | 67.0 | 69.1 | 53.9 | 48.2 | 47.0 | 44.7 | 56.6 | ||

| LAT - Other reasons | 4.8 | 8.0 | 11.4 | 5.1 | 6.8 | 19.5 | 11.5 | 12.1 | ||

| N LAT | 498 | 968 | 149 | 609 | 530 | 679 | 853 | 882 | 1429 | 589 |

| N Total (Unweighted) | 11,986 | 11,226 | 10,000 | 12,796 | 10,214 | 7,150 | 9,922 | 10,079 | 14,824 | 13,538 |

Note: Weighted data

The middle panel of Table 2 shows that the majority of respondents in LAT unions intend to live together within the next three years. This percentage is lowest in Russia (55%) and Lithuania (57%), and highest in France (75%) and Romania (79%). These results suggest that LAT unions may be an advanced stage in the courtship process. However, significant minorities of those in LAT unions in both Western and Eastern European countries do not plan to co-reside.

In the bottom panel of the table is the distribution of individuals in different types of LAT union. This information is not available for Norway and Hungary. Practical constraints are mentioned most often. The percentage of respondents mentioning practical constraints ranges from 45% in Germany to 69% in Georgia. Employment-related reasons are the most common reasons mentioned by respondents in France and Germany. In Eastern European countries housing-related reasons are mentioned most often, followed by financial reasons (results not shown). Higher percentages of those in LAT relationships say they are not ready to live together in Romania (25%), Lithuania (23%), and Bulgaria (21%) than in the other countries. In Georgia, where LAT unions are rare, only 6% said that they were not ready. The desire for independence is a more common reason for being in a LAT union in Germany (23%) and France (17%) than elsewhere. The percentage of respondents not living with their partner that mention this reason in Romania, Russia, Bulgaria, and Lithuania varies between 12% and 15%. Again, the percentage is lowest in Georgia, at 8%. The percentage of respondents who prefer to be in a LAT union because of the practical advantages of this living arrangement is low across all countries. Finally, there is a relatively small residual category of people who say that they are in a LAT relationship for other reasons, although this category is relatively large in Belgium. Unfortunately the GGS does not provide information that allows us to further specify these “other” responses. Overall, these results are in line with hypothesis 5a, that LAT unions are more likely to be for reasons of independence in Western European countries and for practical reasons in Eastern European countries.

4.2 Multivariate analyses

4.2.1 Correlates of LAT relationships and other union statuses

Table 3 summarizes the results of a multinomial logistic regression of individuals' attitudes, socioeconomic and demographic characteristics, and country of residence on union status. The table shows the relative risk ratios for the chance of being in a LAT relationship rather than in each of the other union statuses.

Table 3.

Relative risk ratios from multinomial logistic regression of selected independent variables on union status

| Lat vs Single | Lat vs Cohabiting | Lat vs Married | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRR | RRR | RRR | ||||

| Religious importance | 0.94 | ** | 1.11 | ** | 0.99 | |

| Traditional marriage attitude | 0.95 | ** | 1.11 | ** | 0.68 | ** |

| Gender equality | 0.96 | ** | 0.99 | 1.01 | ||

| Experienced union dissolution | 0.59 | ** | 1.09 | ** | 8.24 | ** |

| Had children from former relationship | 1.60 | ** | 1.29 | ** | 1.30 | ** |

| Subjective income | 1.16 | ** | 1.03 | 0.97 | ** | |

| Employed | 1.53 | ** | 0.90 | ** | 0.81 | ** |

| Education (mid-level omitted) | ||||||

| Low | 0.67 | ** | 0.64 | ** | 0.81 | ** |

| High | 1.13 | ** | 1.07 | * | 1.08 | * |

| Aged 36 and over | 0.35 | ** | 1.13 | ** | 0.19 | ** |

| Enrolled in higher education | 1.42 | ** | 4.64 | ** | 16.38 | ** |

| Male | 1.31 | ** | 1.16 | ** | 1.22 | ** |

| Country (Bulgaria omitted) | ||||||

| Russia | 1.85 | ** | 1.01 | * | 1.17 | * |

| Georgia | 0.24 | ** | 0.17 | ** | 0.39 | ** |

| Hungary | 0.78 | ** | 0.66 | 1.04 | ||

| Romania | 1.05 | 1.23 | 0.91 | |||

| Lithuania | 0.60 | ** | 0.79 | 0.88 | ||

| Belgium | 2.09 | ** | 0.94 | 1.11 | ||

| Germany | 1.45 | ** | 1.29 | ** | 2.11 | ** |

| France | 1.86 | ** | 0.74 | ** | 1.87 | ** |

| Norway | 1.86 | ** | 0.73 | ** | 1.81 | ** |

| Constant | 0.21 | ** | 0.28 | ** | 0.33 | ** |

Note: Weighted data, N=104,830

p < .05

p < .01

The results partially support hypothesis (H1a), that people with liberal attitudes are more likely to be in a LAT relationship compared to being married or cohabiting. The relative risk of being in a LAT relationship rather than in a marriage is lower if respondents hold a traditional attitude towards marriage: that is, LAT unions are more likely when respondents oppose traditional marriage. However, contrary to H1a, a high level of religiosity and a traditional marriage attitude increases the relative risk of respondents being in a LAT relationship compared to being in a cohabiting relationship.

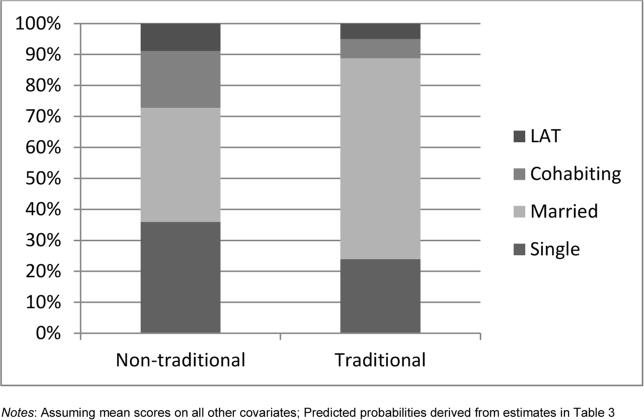

Furthermore, a high level of religiosity, a traditional marriage attitude, and a progressive view on gender roles decrease the relative risk that respondents are in a LAT relationship rather than single. To illustrate what the effects of marriage attitude imply for the distribution of respondents across union status we calculated predicted probabilities, comparing respondents who strongly disagreed and those who strongly agreed with the statement that marriage is an outdated institution, with all other variables set to the sample mean (see Figure 1). As expected, Figure 1 shows that the main difference is that the probability of respondents being married is much lower (37%) among respondents who feel that marriage is an outdated institution than among those who disagree with that statement (65%). Thinking that marriage is outdated increases the probability of being single by about 50% (from 24% to 36%), almost doubles the probability of being in a LAT union (from 5% to 9%), and triples the probability of being in a cohabiting union (from 6% to 18%).

Figure 1.

Predicted probabilities of union status for respondents with traditional and non-traditional marriage attitudes

The results in Table 3 provide more support for our hypotheses about the association between previous family experiences and LAT unions (H2a). Respondents who have experienced divorce or widowhood are much more likely to be in a LAT union than married. To illustrate (results not shown), the predicted probability of being in a LAT relationship almost doubles from 5% to 9% for those who were previously married compared to for those who were not. If respondents have children from a previous relationship the expected probability of being in a LAT is 8% compared to 6% if they have no children from previous relationships (results not shown).

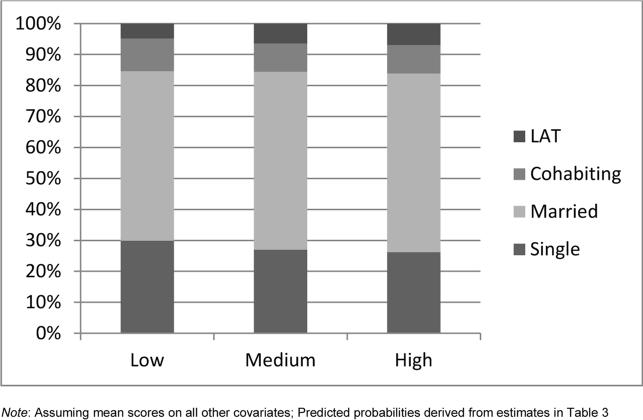

We find only partial support for our hypothesis about the association between socioeconomic status and LAT union status (H3a). As expected, subjective income and being employed increase the risk of being in a LAT relationship rather than being single, and decrease the risk of being in a LAT relationship rather than being married. However, no statistically significant effects of subjective income on the odds of being in a LAT relationship or cohabiting were observed. The effects for educational attainment are not in line with expectations. The higher the educational attainment of respondents is, the higher the relative likelihood that they are in a LAT relationship. This is illustrated by the predicted probabilities presented in Figure 2. The predicted percentage of respondents being in a LAT relationship is 5% among respondents with a low level of education, 6% among respondents with a medium level of education, and 7% among respondents with a high level of education. Although the association between union status and educational attainment is statistically significant, these percentages also show that being in a LAT relationship is only experienced by a small minority, even among the highly educated.

Figure 2.

Predicted probabilities of union status for respondents with low, medium, and high levels of educational attainment

As expected, Table 3 shows that the association between age and union status is strong. The relative risk of respondents being in a LAT relationship compared to being married decreases with age. However, the relative risk of being in a LAT relationship compared to cohabiting is higher among those aged 36 and older than among those who are younger. Also unexpectedly, the relative risk of being in a LAT relationship compared to being single is lower for older people. Overall, these relative risks add up to predicted percentages showing that – in line with H4a – the percentage of respondents in a LAT relationship is 8% among the 18 to 35 year olds, but is only 3% among those aged 36 and older (not shown). The results in Table 3 also support our expectation that people who are enrolled in higher education are more likely to be in a LAT relationship than in a marital or cohabiting union. Higher education enrollment is also associated with a higher risk of being in a LAT relationship rather than being single. The expected probability of being in a LAT is 17% among those enrolled in higher education, but only 5% among those not in higher education (results not shown).

Finally, men are more likely than women to report being in a LAT relationship, compared to any of the other union statuses. Country differences in relative risk ratios mostly mirror those presented in the descriptive results section (predicted probabilities not shown).

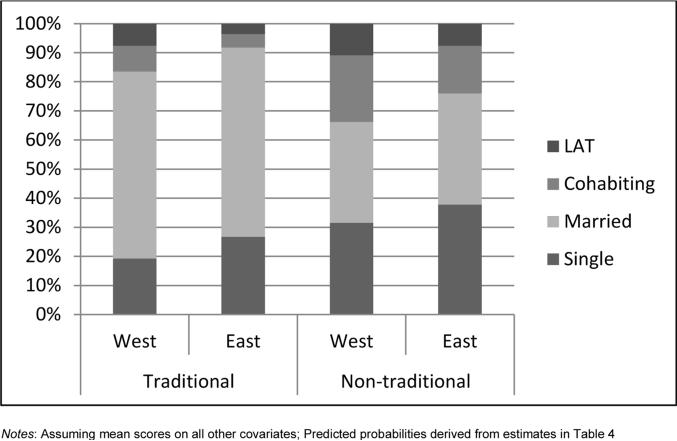

In Table 4, results of the multinomial logistic regression are presented separately for Western and Eastern European countries. Parameter estimates with the same superscript are statistically different in East and West. Wald tests show that all covariates, with the exception of attitudes towards gender equality, differ statistically significantly between East and West. We expected liberal attitudes to matter more in Western than Eastern Europe (H5b). However, the results are opposite to expectations. In particular the association between being in a LAT relationship (vs. married) and marriage attitudes is greater in Eastern than Western Europe (relative risk ratio .66 in the East versus .70 in the West). This is illustrated by the predicted percentages in Figure 3 where non-traditional and traditional attitudes are defined as in Figure 1 (strongly agree that marriage is outdated vs. strongly disagree). In both the West and the East those with non-traditional marriage attitudes are more likely to be cohabiting or in a LAT than those with traditional marriage attitudes. However, the relative increase associated with the difference between traditional and non-traditional attitudes in the percentage in a LAT (or cohabiting) union is higher in the East than in the West.

Table 4.

Relative risk ratios from multinomial regression of selected independent variables on union status, for Eastern and Western Europe

| LAT vs Single | LAT vs Cohabitation | LAT vs Married | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| West | East | West | East | West | East | |||||||

| Religious importance | 0.91 | **a | 1.00 | a | 1.07 | ** | 1.13 | ** | 0.96 | * | 1.00 | |

| Traditional marital attitude | 1.01 | b | 0.92 | **b | 1.13 | ** | 1.13 | ** | 0.70 | **p | 0.66 | **p |

| Gender equality | 0.96 | * | 0.96 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 1.04 | |||||

| Experienced union dissolution | 0.87 | **c | 0.54 | **c | 1.35 | **h | 1.01 | h | 5.38 | **q | 13.23 | **q |

| Had children from former relationship | 1.55 | ** | 1.30 | ** | 1.33 | i | 0.97 | i | 1.90 | **r | 0.79 | **r |

| Subjective income | 1.10 | **d | 1.25 | **d | 0.91 | **j | 1.15 | **j | 0.87 | **s | 1.09 | **s |

| Employed | 1.43 | ** | 1.63 | ** | 0.66 | **k | 1.06 | k | 0.75 | **t | 0.87 | **t |

| Education (mid-level omitted) | ||||||||||||

| Low | 0.80 | **e | 0.53 | **e | 0.97 | l | 0.41 | **l | 0.88 | *u | 0.68 | **u |

| High | 1.08 | 1.21 | * | 0.95 | m | 1.32 | **m | 0.96 | v | 1.25 | **v | |

| Age 36 and over | 0.41 | **f | 0.30 | **f | 1.44 | **n | 0.88 | n | 0.25 | **w | 0.14 | **w |

| Enrolled in higher educationl | 1.75 | **g | 1.18 | **g | 4.20 | ** | 4.43 | ** | 20.56 | **x | 13.23 | **x |

| Male | 1.29 | ** | 1.30 | ** | 1.32 | ** ° | 1.01 | o | 1.16 | ** | 1.28 | ** |

| Country | ||||||||||||

| Bulgaria | ref | ref | ref | |||||||||

| Hungary | 0.73 | ** | 0.56 | ** | 0.85 | * | ||||||

| Romania | 1.01 | 1.17 | 0.85 | * | ||||||||

| Russia | 1.93 | ** | 0.94 | 1.09 | ||||||||

| Georgia | 0.22 | ** | 0.15 | ** | 0.38 | ** | ||||||

| Lithuania | 0.57 | ** | 0.66 | ** | 0.77 | ** | ||||||

| Belgium | ref | ref | ref | |||||||||

| Germany | 0.77 | ** | 1.44 | ** | 1.67 | ** | ||||||

| France | 0.91 | 0.74 | ** | 1.43 | ** | |||||||

| Norway | 0.93 | 0.84 | * | 1.60 | ** | |||||||

| Constant | 0.38 | ** | 0.17 | ** | 0.18 | ** | 0.20 | ** | 0.62 | ** | 0.25 | ** |

Notes: Weighted data; N=104,830

p < .05

p < .01

ref = reference category; Parameter estimates with the same subscript differ at p < .05 between East and West Europe

Figure 3.

Predicted probabilities of union status for respondents with traditional and non-traditional marriage attitudes by European region

There are also clear East-West differences in the association between socioeconomic factors and union status. Whereas in Western European countries the predicted percentage of being in a LAT union is slightly lower for those with high subjective income than for those with low subjective income (10% vs. 8%), the opposite tendency can be observed in Eastern European countries (4% for those with low subjective income and 7% for those with high subjective income) (results not shown).5 Note that the findings for Eastern Europe are contrary to what we expected (i.e., LAT unions were expected to be less likely for those with higher income). Differences between East and West in the percentage of employed and non-employed persons who are in a LAT union are relatively limited even though the relative risk ratios are statistically significant (results not shown).

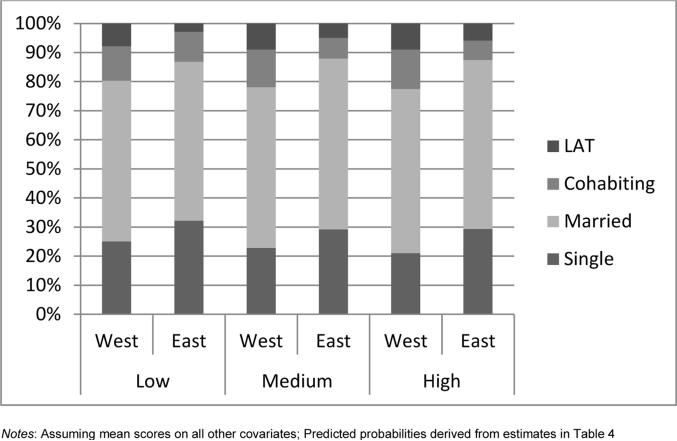

Education is positively associated with being in a LAT union compared to cohabitation and marriage in Eastern Europe, but not in Western Europe. As Figure 4 shows, there is little difference in the percentage in a LAT union between those with low and high education in Western Europe (8% vs. 9%). But in Eastern European countries the educational differences are much larger. Only 3% of those with a low level of education are in a LAT union, and this predicted percentage doubles to 6% among the highly educated. Thus, although educational differences in union status are more pronounced in Eastern European countries than in Western European countries, the differences in Eastern Europe are not in the predicted direction - that the more highly educated would be less likely to be in a LAT union compared to marriage or cohabitation.

Figure 4.

Predicted probabilities of union status for respondents with low, medium, and high levels of educational attainment, by European region

Some other East-West differences are also worth noting. In Eastern Europe those who have children from a previous union are less likely to be in a LAT union compared to marriage or cohabitation. But in Western Europe those who have children from a previous union are more likely to be in a LAT union than married or cohabiting. In both parts of Europe LAT unions are more likely compared to marriage among those who are young than among those who are older.

4.2.2 Correlates of the type of LAT relationship

Table 5 presents the results of our examination of the characteristics associated with different reasons for being in a LAT relationship. As expected, those who hold more traditional marriage attitudes are less likely to be in LAT relationships because they prefer to be independent, rather than in any other type of LAT union (H1b). But contrary to our expectation there is no association between either the importance of religion and type of LAT union or the attitudes favoring gender equality and type of LAT union.

Table 5.

Relative risk ratios from multinomial logistic regression of selected independent variables on type of LAT relationship

| Independent vs. Not ready yet | Independent vs Practical reasons | Independent vs Other reasons | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRR | RRR | RRR | ||||

| Religious importance | 1.02 | 1.03 | 1.05 | |||

| Traditional marriage attitude | 0.91 | * | 0.78 | ** | 0.89 | * |

| Gender equality | 1.01 | 1.02 | 0.94 | |||

| Experienced union dissolution | 1.64 | ** | 1.71 | ** | 1.43 | * |

| Had children from former relationship | 0.95 | 0.82 | 1.15 | |||

| Subjective income | 0.97 | 1.15 | ** | 1.01 | ||

| Employed | 1.18 | 1.11 | 1.40 | * | ||

| Education (mid-level omitted) | ||||||

| Low | 1.04 | 0.93 | 0.99 | |||

| High | 1.05 | 0.91 | 0.93 | |||

| Aged 36 and over | 5.31 | ** | 2.42 | ** | 2.20 | ** |

| Enrolled in higher education | 0.63 | ** | 0.60 | ** | 1.04 | |

| Male | 1.36 | ** | 1.06 | 1.03 | ||

| Country (Bulgaria omitted) | ||||||

| Russia | 1.48 | 0.63 | ** | 0.42 | ** | |

| Georgia | 1.58 | 0.44 | * | 0.23 | ** | |

| Romania | 0.71 | 0.86 | 0.83 | |||

| Lithuania | 0.91 | 0.96 | 0.65 | |||

| Belgium | 1.01 | 0.66 | * | 0.17 | ** | |

| Germany | 1.81 | ** | 1.61 | ** | 0.68 | |

| France | 1.94 | ** | 1.02 | 0.40 | ** | |

| Constant | 0.61 | 0.27 | ** | 2.76 | * | |

Note: Weighted data, N=5,252

p < .05

p < .01

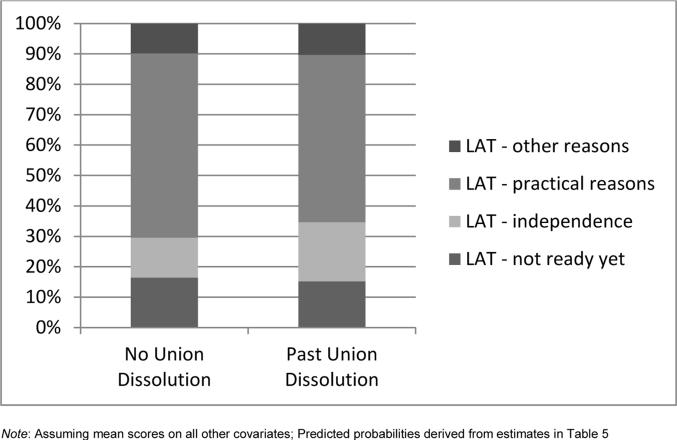

Table 5 also shows partial support for our expectation (H2b) that previous union disruption and children from a previous relationship will be associated with being in a LAT union to preserve independence or for practical reasons. Those who have experienced divorce or have been widowed are more likely to report that they are in LAT unions for reasons of independence than for other reason (see Figure 5). The predicted percentage of those in LAT unions because they value independence is almost 1.5 times as high if they have experienced a union dissolution (divorce or widowhood) at 19% than if they have not experienced a union dissolution (13%), as shown in Figure 5. The predicted percentage of those in LAT unions who say that they are in a LAT union for practical reasons is lower among those who have experienced a union dissolution (55% vs. 60%). There is no statistically significant difference in the risk of there being different types of LAT union among respondents with and without children from previous relationships.

Figure 5.

Predicted probabilities of different types of LAT relationship for respondents who have experienced a union dissolution either by divorce or widowhood and those who have not experienced a union dissolution

Although we expected that people with more socioeconomic resources would be less likely to be in a LAT relationship for practical reasons compared to the other types of LAT relationship (H3b), the results in Table 5 show little evidence of this. Only subjective income is positively associated with being in a LAT union for reasons of independence compared to practical reasons.

Table 5 also shows that older people are more likely to say that their LAT relationships are to support their independence, compared to other reasons. Conversely, younger people are more likely to say that they are not ready to live together (H4c). Interestingly, the predicted percentages of respondents in the different types of LAT union by age show that the percentage of respondents who are in LATs for independence is twice as high at older ages (i.e., age 36+) than at younger ages (28% vs. 13%) (not shown). The other developmental stage hypothesis (H4d) is also supported by the results in Table 5. Those who are enrolled in higher education are much less likely to say that their LAT unions are for independence rather than for practical reasons or because they are not ready to live together.

In additional analyses we examined whether the effects of correlates of LAT type differed between Western and Eastern European countries. The results indicate few East-West differences (results not shown).

5. Conclusion and discussion

In line with other family changes that have been interpreted as constituting a Second Demographic Transition, living-apart-together relationships may indicate that independence and autonomy are valued more and commitment is valued less in intimate relationships. Yet to date few studies have examined the meaning of LAT relationships: Is LAT indeed a long-term relationship substituting for marriage and cohabitation or just a dating relationship? This paper examines the prevalence of LAT unions in different European countries, the meaning attached to LAT unions in these countries, and whether that meaning varies across the continent.

Our results show that LAT is not a very common relationship type. In all countries, LAT relationships were less common than marriage, cohabitation, and singlehood. Less than 10% of adults were in a LAT relationship. Although these figures suggest LAT to be a rather marginal phenomenon it is important to realize that these figures are a snapshot in time – both historical and individual time. It may well be that the number of LAT relationships has increased in some countries over the past decades. In addition, the significance of LAT depends in part on whether individuals have ever been in a LAT relationship, not just who is in one at a particular moment in time.

Information on union intentions and the reasons respondents gave for being in a LAT union allowed us to delve more deeply into the meaning respondents attach to their LAT relationships. In all countries the majority of respondents intended to live together within three years, with co-residence intentions ranging from 55% in Russia to 79% in Romania. In all countries, practical reasons were cited most often for people not living together, ranging from nearly 50% in Germany to a little over 70% in Georgia. The other reasons – not ready yet, independence, and other reasons – were mentioned far less often. These findings suggest that LAT is mainly a temporary living arrangement. As soon as circumstances allow, a majority of those in LAT unions are likely to move in together. This pattern is consistent with the view of LAT relationships as a stage in the union formation process for most people in all of the countries in this study, rather than as an alternative to co-residential union.

Although the general picture is that LAT unions are a marginal phenomenon driven by practical considerations, countries vary in the extent to which this is the case. The prevalence of LAT unions was generally higher in Western European countries (close to 10%) than in Eastern European countries (5% or less). Russia was an exception to this rule, with a percentage of LAT relationships that was comparable to that in France and Germany. The East-West divide corroborates the idea that LAT relationships are more common in countries, such as the Western European countries, that have progressed further in the Second Demographic Transition where there are more acceptable alternatives to marriage (Liefbroer and Fokkema, 2008). Also in line with Second Demographic Transition theory is our descriptive finding that LAT unions are somewhat more likely to be for reasons of independence in Western Europe than in Eastern Europe. This East-West difference is not as consistent as for the difference in the prevalence of LAT unions as a whole.

Our findings about the correlates of LAT relationships suggest that LAT is not an alternative to singlehood. The correlates of being in a LAT relationship differ from the correlates of being single, suggesting that the reasons for being single are qualitatively different from the reasons for being in a LAT relationship. This conclusion holds for both Eastern and Western Europe. Singlehood seems to follow from constraints in the marriage market, as evidenced by our finding that people with few socioeconomic resources are more likely to be single than in a LAT relationship.

Our findings also suggest that LAT is rarely an alternative to marriage and cohabitation but rather a stage in the union-formation process. If LAT unions were an alternative, people with liberal attitudes would be more likely to be in a LAT relationship than in any co-residential relationship. Although those with liberal attitudes were more likely to be in LAT unions than in marriage, liberal attitudes increased the likelihood that an individual would be cohabiting rather than in a LAT union. Cohabitation rather than LAT relationships are likely to be chosen by Europeans valuing autonomy and independence. Moreover, the strong association between life stage and financial constraints on the one hand and being in a LAT relationship on the other hand suggest that LAT is not so much a choice as the result of practical constraints, because a co-residential union is at odds with the young adult role of being a student or because limited financial means prevent people from sharing a household.

For specific groups, however, LAT relationships may be an alternative to marriage and cohabitation. Divorced and widowed persons and those who had children from a previous relationship were more likely to be in a LAT relationship than a co-residential union. Although practical constraints rather than a preference for independence may drive the couple's decision to live apart, our findings suggest that respondents view their arrangement as one that preserves independence (vs. for other reasons). LAT unions also may be an alternative to co-residential unions for older individuals. Although older persons are much more likely to be married than in a LAT relationship than those who are young, older persons who are in LAT unions are more likely to do so for autonomy-related reasons than their younger counterparts.

Given that the highly educated are often thought to be among the frontrunners in the Second Demographic Transition, especially highly educated persons may consider LAT unions to be an alternative to marriage or cohabitation. Education is an indication of individuals' cultural resources as well as their economic resources. We find that socioeconomic resources other than education are associated with being in a co-residential union (cohabitation or marriage) rather than in a LAT union. By contrast, education is associated with being in a LAT union rather than a co-residential union. The highly educated may be a cultural elite resisting traditional norms and perhaps becoming the first to embrace LAT relationships as a new relationship type.

Some noteworthy differences between Eastern and Western Europe occur. Contrary to what we expected on the basis of the Second Demographic Transition theory, liberal attitudes were not stronger predictors in Western than in Eastern Europe: on the contrary. Liberal marriage attitudes were stronger predictors of being in a LAT relationship or cohabitation in the East than in the West. One potential explanation is that strong norms favoring marriage in Eastern Europe make LAT a rare phenomenon that is only adopted by a cultural elite that resists these norms. At the same time, the cultural elite in Eastern European countries may sometimes prefer LAT relationships to cohabitation as LAT relationships outwardly conform more to these societies' traditional moral expectations, thereby increasing the acceptability of their behavior and reducing potential conflicts with parents and other network members who hold strong norms favoring marriage. We find more pronounced educational differences in Eastern Europe, with more highly educated individuals being more likely to be in a LAT union than those who are less educated. This is consistent with our line of reasoning. In the West, those who have children from previous relationships are more likely to opt for a LAT relationship than in the East.

A tentative conclusion is that LAT is more often a stage in the union formation process than an alternative to marriage and cohabitation, as has been suggested by others (e.g., Castro-Martín, Domínguez-Folguers, and Martín-García 2008; Duncan and Phillips 2010). Yet some groups act as if LAT is a substitute for marriage and cohabitation, and these groups appear to differ between East and West. In Eastern Europe a cultural, highly educated elite seems to be the first to resist traditional marriage norms and embrace LAT (and cohabitation) as alternative living arrangements, whereas this is less the case in Western Europe. In Western Europe, LAT unions are mainly an alternative for persons having experienced prior events in the family domain, as has also been found in prior research (De Jong Gierveld 2002; Evertsson and Nyman 2013; Régnier-Lollier, Beaujouan, and Villeneuve-Gokalp 2009).

The GGS data provide an invaluable opportunity to examine cross-national variation in LAT relationships, but they have three significant limitations. First, our results, and especially the distribution of respondents across LAT union types in our LAT typology of reasons for these unions, depend on the questions available in the GGP. Qualitative research shows that people often have multiple reasons for living apart together (Duncan et al. 2013; Levin and Trost 1999; Roseneil 2006). People may have difficulty choosing between the reasons the GGS provided for being in a LAT union or they may both prefer to live apart but also face constraints that limit their ability to co-reside (Roseneil 2006). It also may be ambiguous whether people consider a certain circumstance, such as having children from a previous relationship, as a constraint keeping them from living together or as a reason to prefer to live independently. Another concern is that the typology allowed by the GGS data is not exhaustive, given the substantial minority of respondents who provide other reasons for living together than the ones listed in the survey. Unfortunately the responses for this residual category are not available for analysis. Despite these limitations, the patterns of correlations we demonstrate suggest that our typology taps into an important distinction among those who live apart together. But future research, both qualitative and quantitative, is needed to corroborate our conclusions.

A second limitation is that we focus only on prevalence rates, but these are a function of entries and exits from the different union statuses. It is important to examine the extent to which LAT unions are short or longer-term unions, and whether duration varies by life stage and economic or cultural context. Cross-national panel data are needed to address this concern. Prevalence rates may underestimate the significance of LAT unions in the family system, because the significance of these relationships may depend on whether or not an individual has ever been in a LAT relationship.

Finally, because our data included relatively few people in a LAT relationship, especially in Eastern European countries, we are cautious about drawing definite conclusions about the differences between Eastern and Western Europe and about the different types of LAT union. We had too few people in LAT relationships to go beyond the distinction between East and West to study the correlates of LAT relationships in separate countries. We encourage future research to replicate our study with larger samples and in countries in Southern and Northern Europe now lacking in the GGS dataset. This also would allow a more thorough examination of cross-national differences in the prevalence and meaning of LAT unions. The institutional arrangements that vary across countries, including differences in welfare regimes, may influence individuals' decisions about being in a LAT union rather than a co-residential union.

Acknowledgements

This research results from collaboration between members of the Relations-Cross-Nations (RCN)-network. RCN meetings have been supported by: (a) a grant from Utrecht University within the University of California-Utrecht University Collaborative Grant Program (2009), (b) an RFP-grant from the Population Association of America (2010/11), (c) a grant from the Spanish Ministry of Science (2010), and (d) grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation and the University of Lausanne/FORS (2011). Earlier versions of the paper were presented at the 2011 Annual meeting of the Population Association of America (March 31-April 2, Washington, DC) and the European Population Conference 2012 (June 13-16, Stockholm, Sweden). This project was supported in part by the California Center for Population Research at UCLA (CCPR), which receives core support (R24-HD041022) from the U.S. Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). We thank the editor and anonymous reviewers for helpful suggestions.

Footnotes

We also experimented with a more fine-grained age classification, but this led to relatively small numbers of respondents if classified by union status, age category, and country.

Respondents with low subjective income are those who stated that they could only make ends meet with great difficulty; respondents with high subjective income are those who stated that they could make ends meet very easy.

References

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55(5):469–480. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. A treatise on the family. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Casper LM. American families. Population Bulletin. 2000;55:3–42. [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld H-P, Huinink J. Human capital investments or norms of role transition? How women's schooling and career affect the process of family formation. American Journal of Sociology. 1991;97(1):143–168. doi:10.1086/229743. [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass L, Lu H-H. Trends in cohabitation and implications for children's family contexts in the United States. Population Studies. 2000;54(1):29–41. doi: 10.1080/713779060. doi:10.1080/713779060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Martín T, Domínguez-Folguers M, Martín-García T. Not truly partnerless: Non-residential partnerships and retreat from marriage in Spain. Demographic Research. 2008;18(16):438–468. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2008.18.16. [Google Scholar]

- Clausen JS. Adolescent competence and the shaping of the life course. American Journal of Sociology. 1991;96(4):805–842. doi:10.1086/229609. [Google Scholar]

- De Graaf PM, Kalmijn M. Alternative routes in the remarriage market: Competing-risk analyses of union formation after divorce. Social Forces. 2003;81(4):1459–1498. doi:10.1353/sof.2003.0052. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong Gierveld J. The dilemma of repartnering: Considerations of older men and women entering new intimate relationships in later life. Ageing International. 2002;27(4):61–78. doi:10.1007/s12126-002-1015-z. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong Gierveld J. Remarriage, unmarried cohabitation, Living Apart Together: Partner relationship following bereavement or divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66(1):236–243. doi:10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00015.x. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong Gierveld J. Living apart together in The Netherlands: Incidence, and determinants of short-term and long-term relationships. Gerontologist. 2008;48:88. [Google Scholar]

- De Jong Gierveld J, Latten J. Incidentie en achtergronden van transitionele en duurzame latrelaties. Bevolkingstrends. 2008;3:29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan S, Phillips M. People who live apart together (LATs) – how different are they? The Sociological Review. 2010;58(1):112–134. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954X.2009.01874.x. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan S, Carter J, Phillips M, Roseneil S, Stoilova M. Why do people live apart together? Families, Relationships and Societies. 2013;2(3):323–338. doi:10.1332/204674313X673419. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G. The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Polity Press; Cambridge, UK: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Evertsson L, Nyman C. On the other side of couplehood: single women in Sweden exploring life without a partner. Families, Relationships and Societies. 2013;2(1):61–78. doi:10.1332/204674313X664707. [Google Scholar]

- Fenger HJM. Welfare regimes in Central and Eastern Europe: Incorporating post-communist countries in a welfare regime typology. Contemporary Issues and Ideas in Social Sciences. 2007;3(2):1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Fokkema T, Liefbroer AC. Trends in living arrangements in Europe: Convergence or divergence? Demographic Research. 2008;19(36):1351–1417. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.36. [Google Scholar]

- Gender and Generations Program . About GGP. Gender and Generations Program. [electronic resource] 2012. www.ggp-i.org. [Google Scholar]

- Haskey J. Living arrangements in contemporary Britain: Having a partner who usually lives elsewhere and living apart together (LAT). Population Trends. 2005;122:35–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskey J, Lewis J. Living-apart-together in Britain: Context and meaning. International Journal of Law in Context. 2006;2(1):37–48. doi:10.1017/S1744552306001030. [Google Scholar]

- Hiekel N, Liefbroer AC, Poortman A-R. Understanding diversity in the meaning of cohabitation across Europe. European Journal of Population. 2014;30(4):391–410. doi:10.1007/s10680-014-9321-1. [Google Scholar]

- Heuveline P, Timberlake JM. The role of cohabitation in family formation: The United States in comparative perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;66(5):1214–1230. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00088.x. doi:10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan K. The rise of cohabitation and childbearing outside marriage in Western Europe. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family. 2001;15(1):1–21. doi:10.1093/lawfam/15.1.1. [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan K. Unmarried cohabitation and parenthood in Britain and Europe. Law & Policy. 2004;26(1):33–55. doi:10.1111/j.0265-8240.2004.00162.x. [Google Scholar]

- Klijzing E. ‘Weeding’ in the Netherlands: First-union disruption among men and women born between 1928 and 1965. European Sociological Review. 1992;8(1):53–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lesthaeghe R. The unfolding story of the Second Demographic Transition. Population and Development Review. 2010;36(2):211–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00328.x. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liefbroer AC, Billari FC. Bringing norms back in: a theoretical and empirical discussion of their importance for understanding demographic behaviour. Population, Space and Place. 2010;16(4):287–305. doi:10.1002/psp.552. [Google Scholar]

- Liefbroer AC, Fokkema T. Recent trends in demographic attitudes and behaviour: Is the Second Demographic Transition moving to Southern and Eastern Europe? In: Surkyn J, Deboosere P, van Bavel J, editors. Demographic challenges for the 21st century. A state of the art in demography. Vrije Universiteit Press; Brussels: 2008. pp. 115–141. [Google Scholar]

- Levin I. Living apart together. A new family form. Current Sociology. 2004;52(2):223–240. doi:10.1177/0011392104041809. [Google Scholar]

- Levin I, Trost J. Living apart together. Community, Work & Family. 1999;2(3):279–294. doi:10.1080/13668809908412186. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK. A theory of marriage timing. American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94(3):563–591. doi:10.1086/229030. [Google Scholar]

- Poortman A. The first cut is the deepest? The role of the relationship career for union formation. European sociological review. 2007;23(5):585–598. doi:10.1093/esr/jcm024. [Google Scholar]

- Poortman A, Liefbroer AC. Singles’ relational attitudes in a time of individualization. Social Science Research. 2010;39(6):938–949. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2010.03.012. [Google Scholar]

- Pyke KD. Women's employment as gift or burden? Marital power across marriage, divorce, and remarriage. Gender & Society. 1994;8(1):73–91. doi:10.1177/089124394008001005. [Google Scholar]

- Régnier-Lollier A, Beaujouan E, Villeneuve-Gokalp C. Neither single, nor in a couple: A study of living apart together in France. Demographic Research. 2009;21(4):75–108. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2009.21.4. [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss RR, VandenHeuvel A. Cohabitation: a precursor to marriage or an alternative to being single? Population and Development Review. 1990;16(4):703–726. doi:10.2307/1972963. [Google Scholar]