Abstract

The control and alteration of key regulatory enzymes is a determinant of the reactions and pathways of intermediary metabolism in mammalian cells. An important mechanism in the metabolic control is the hormonal regulation of the genes associated with the transcription and the biosynthesis of these key enzymes. The secretory epithelial cells of the prostate gland of humans and other animals posses a unique citrate-related metabolic pathway regulated by testosterone and prolactin. This specialized hormone-regulated metabolic activity is responsible for the major prostate function of the production and secretion of extraordinarily high levels of citrate. The key regulatory enzymes directly associated with citrate production in the prostate cells are mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase, pyruvate dehydogenase, and mitochondrial aconitase. Testosterone and prolactin are involved in the regulation of the corresponding genes associated with these enzymes (which we refer to as “metabolic genes”). The regulatory regions of these genes contain the necessary response elements that confer the ability of both hormones to control gene transcription. In this report, we describe the role of protein kinase c (PKC) as the signaling pathway for the prolactin regulation of the metabolic genes in prostate cells. Testosterone and prolactin regulation of these metabolic genes (which are constitutively expressed in all mammalian cells) is specific for these citrate-producing cells. We hope that this review will provide a strong basis for future studies regarding the hormonal regulation of citrate-related intermediary metabolism. Most importantly, altered citrate metabolism is a persistent distinguishing characteristic (decreased citrate production) of prostate cancer (PCa) and also (increased citrate production) of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). An understanding of the role of hormonal regulation of metabolism is essential to understanding the pathogenesis of prostate disease. The relationships described for the regulation of prostate cell metabolism provides insight into the mechanisms of hormonal regulation of mammalian cells in general.

Keywords: Aspartate Aminotransferase, Mitochondrial Aconitase, Pyruvate Dehydrogenase, Protein Kinase C, Prostate Cancer, Zinc, Aspartate Transport, Krebs Cycle, Androgen Response Element, AP-1

Introduction

Citrate metabolism plays a uniquely essential role in the normal function of the prostate gland of humans and other animals. The normal human prostate has the major function of accumulating and secreting extremely high levels of citrate that account for the enormous citrate concentration in prostatic fluid. For example, human prostate tissue citrate levels are in the range of 8000–20 000 nmol/g tissue concentration, as compared to 100–500 for virtually all other soft tissues; prostatic fluid contains 20–100mM citrate compared to blood plasma levels of 0.1–0.2mM. This capability resides within the glandular secretory epithelial cells of the prostate peripheral zone. We refer to these uniquely specialized cells as “citrate-producing” cells. To achieve this function, the prostate cells possess unique metabolic relationships that deviate from the typical intermediary metabolism of most mammalian cells (for reviews see [1–4]). Prostate citrate production is hormonally regulated by testosterone and prolactin [5, 6]. Recent studies have provided important insights into the role and mechanisms of the hormonal regulation of citrate-related metabolism of the prostate epithelial cells, especially at gene regulation level. Moreover, altered citrate metabolism is an important factor in the pathogenesis of prostate disease. Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) involves the proliferation of citrate-producing secretory epithelial cells. In contrast, prostate cancer (PCa) is always characterized by a dramatic decrease in citrate levels. Prostate malignancy involves a metabolic transformation of normal citrate-producing peripheral zone epithelial cells to malignant cells that have lost the ability to produce high citrate levels and are citrate-oxidizing cells. This review provides current and new concepts of testosterone and prolactin control of prostate citrate metabolism, which should contribute to an understanding of hormonal regulation of intermediary metabolism in normal cell function and in the pathogenesis of metabolic-associated disease.

Key regulatory enzymes of net citrate production; the metabolic genes

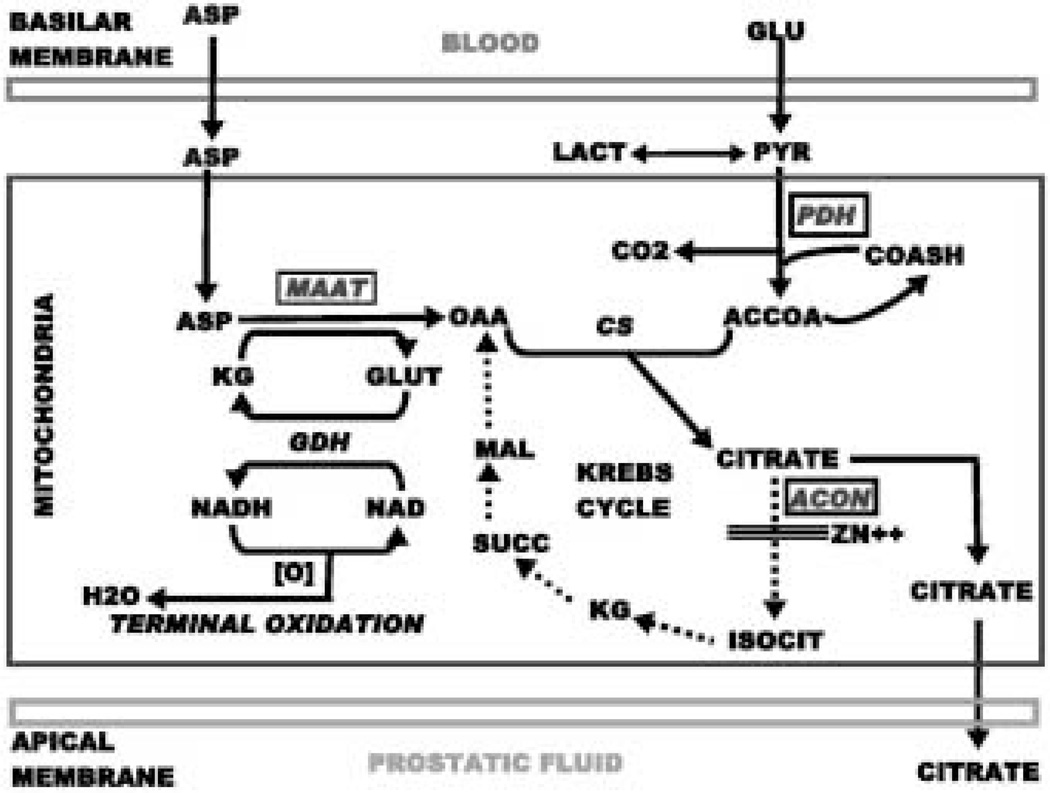

The unique metabolic pathway of “net citrate production” is represented in Fig.1. Net citrate production occurs when the rate of citrate synthesis exceeds the rate of citrate oxidation. It is important to emphasize that in essentially all other mammalian cells, citrate is a key intermediate in cell metabolism, while being an end-product of cell metabolism in prostate cells. In addition, aspartate is a synthetic product of intermediary metabolism in most mammalian cells, and is therefore a non-essential amino acid. In contrast, aspartate is required and utilized in the production of citrate in prostate cells as represented in Fig.1. The key regulatory enzymes involved in citrate synthesis in citrate-producing cells are mAAT and PDH. Since citrate accumulation requires a continual source of OAA, these prostate cells utilize aspartate via transamination as the source of OAA. The source of acetyl CoA is derived from glucose via the oxidation of pyruvate. In typical mammalian cell metabolism, the synthesized citrate is readily oxidized via the Krebs cycle. This is not the case for citrate- producing prostate cells. It has now been established that citrate oxidation is inhibited at the mitochondrial (m-)aconitase reaction, which is the first step in the oxidation of citrate via the Krebs cycle [7–9]. Consequently, the Krebs cycle is aborted in citrate-producing prostate epithelial cells. Thus, mAAT, PDH, and m-aconitase are the key regulatory enzymes involved in the regulation of prostate citrate production. We refer to the corresponding genes associated with the expression of these enzymes as “metabolic genes”.

Fig. 1.

The pathway of net citrate production in prostate secretory epithelial cells. The key regulatory enzymes are represented in the rectangles. PDH, pyruvate dehydrogenase; CS, citrate synthase; mAAT, mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase; ACON, aconitase; GDH, glutamate dehydrogenase.

Testosterone regulation of prostate citrate synthesis

Since the initial report of Humphrey and Mann [10], numerous studies have established that testosterone regulates prostate citrate production (see [5,11] for early reviews). However, the mechanism of testosterone regulation of citrate production could not be elucidated until the metabolic pathway of net citrate production had been established (Fig.1). This was achieved through a series of studies that approximates the period of 1981–1995 (for reviews see [2,12]). Testosterone stimulates aspartate utilization and transamination, which results in increased OAA production for citrate synthesis by prostate epithelial cells [13–16]. This effect is a result of hormone-induced increases in gene expression and subsequent biosynthesis of mAAT [17–19].

However, testosterone stimulation of OAA production will not lead to increased citrate synthesis without increased acetyl CoA availability. This is attained by the stimulatory effect of testosterone on pyruvate oxidation as initially reported by Harkonen [20] and later confirmed by our studies [21, 22]. It is now evident that testosterone increases PDH activity. This is achieved by the stimulation of the expression and biosynthesis of the E1a regulatory component of the PDH complex [23]. Thus, the PDHE1a gene, like the mAAT gene, is an androgen-responsive gene in prostate epithelial cells. It is possible that other components of the PDH complex might also be regulated by testosterone, but further studies are required to establish such possibilities. It is especially notable that both the mAAT and PDHE1a genes are similarly responsive to testosterone, as the tandem regulation of both enzymes is necessary to increase the net synthesis of citrate. In this manner, testosterone can regulate the rate of citrate synthesis in prostate cells.

Testosterone regulation of citrate oxidation

In typical mammalian cell metabolism, citrate does not accumulate since the rate of citrate oxidation exceeds the rate of citrate synthesis. In prostate epithelial cells, citrate oxidation is impaired by the presence of a uniquely limited m-aconitase activity (Fig.1). Therefore, one would expect that testosterone should have a role in the regulation of m-aconitase activity. The anticipated effect of testosterone, which is consistent with its role in increasing net citrate production, would be to inhibit citrate oxidation. This expectation has been observed with rat lateral prostate cells in which testosterone decreases citrate oxidation. The effect is achieved by a decrease in the level and activity of maconitase that results from testosterone inhibition of m-aconitase gene expression [24].

In contrast to the inhibitory effect on citrate oxidation in lateral prostate cells, testosterone increases the rate of citrate oxidation in rat ventral prostate cells. This is achieved by testosterone stimulation of m-aconitase gene expression that leads to increased biosynthesis of m-aconitase enzyme and increased aconitase enzyme activity [24–27]. Seemingly, an increase in citrate oxidation would be antithetical to the testosterone effect in increasing net citrate production. To reconcile this, we calculated that corresponding testosterone-induced increases in both the rate of citrate synthesis and the rate of citrate oxidation will result in a net increase in citrate production [15], which is due to the inherent low level of m-aconitase activity that characterizes these cells. Therefore, testosterone will increase net citrate production while also increasing citrate oxidation. The latter is likely essential to provide the ATP and other metabolic requirements associated with the other stimulatory effects of testosterone on these cells.

Like rat ventral prostate cells, testosterone stimulates the transcription of m-aconitase, the level of m-aconitase enzyme, and citrate oxidation in the androgen-responsive LNCaP cells while having no effect on androgen-independent PC-3 cells (human malignant prostate cell lines) [27]. However, when PC-3 cells are transfected with androgen receptor, testosterone stimulates the expression of the m-aconitase gene. Currently, no information exists on normal human citrate-producing prostate epithelial cells. However, testosterone stimulates the transcription of m-aconitase, the level of m-aconitase, and citrate oxidation of normal freshly prepared pig prostate epithelial cells, which are citrate-producing cells closely homologous to human prostate [26,27]. Based on these studies, one could speculate that normal human prostate cells likely exhibit the same effect of testosterone as human cell lines and normal pig prostate cells, that is, stimulation of m-aconitase gene expression and citrate oxidation.

Prolactin regulation of prostate citrate production

Despite the accumulation of substantial information implicating prolactin as an important regulator of prostate growth and function (for reviews see [6, 28]), the importance of this hormone in normal and pathological prostate has not received appropriate attention. Grayhack’s group first demonstrated that prolactin was involved in the regulation of prostate citrate production in rat studies [29, 30]. Moreover, the lateral prostate, as compared with the ventral and dorsal lobes, was the major target for this prolactin effect. The observations in rat studies have subsequently been corroborated [31, 32]. Prolactin stimulation of citrate production was also observed with pig [32] and monkey prostate [33]. These combined studies support the strong likelihood that prolactin is an important regulator of prostate citrate production in humans. Unfortunately, in vivo studies of this role of prolactin in humans have not yet been reported. Although the role of prolactin in female reproduction is well-established, no corresponding function for prolactin in males has been identified. It seems evident that a reproductive function of prolactin in males is the regulation of citrate production and secretion in prostatic fluid. Indeed, prolactin might be more important than testosterone in regard to this function.

The mechanism by which prolactin regulates prostate citrate production has recently been addressed. Studies with rat lateral prostate epithelial cells revealed that prolactin stimulates mAAT gene expression and mAAT biosynthesis [6, 32,34–36] and stimulates PDHE1a expression, PDHE1a levels, and pyruvate oxidation [23,37]. In contrast to the stimulatory effect on mAAT and PDH, prolactin inhibits the gene expression of m-aconitase and the level of m-aconitase resulting in decreased citrate oxidation [27, 38].

In contrast to its inhibitory effects on m-aconitase in lateral prostate, prolactin increases the expression of m-aconitase and citrate oxidation of ventral prostate epithelial cells. Studies with LNCaP and PC-3 cells and pig prostate epithelial cells have revealed that prolactin increases the transcription of mAAT, PDHE1a, and m-aconitase, which results in increased citrate synthesis and increased citrate oxidation [26,27]. These are the same effects as those observed with testosterone as described above.

Testosterone regulation of the metabolic genes in prostate cells

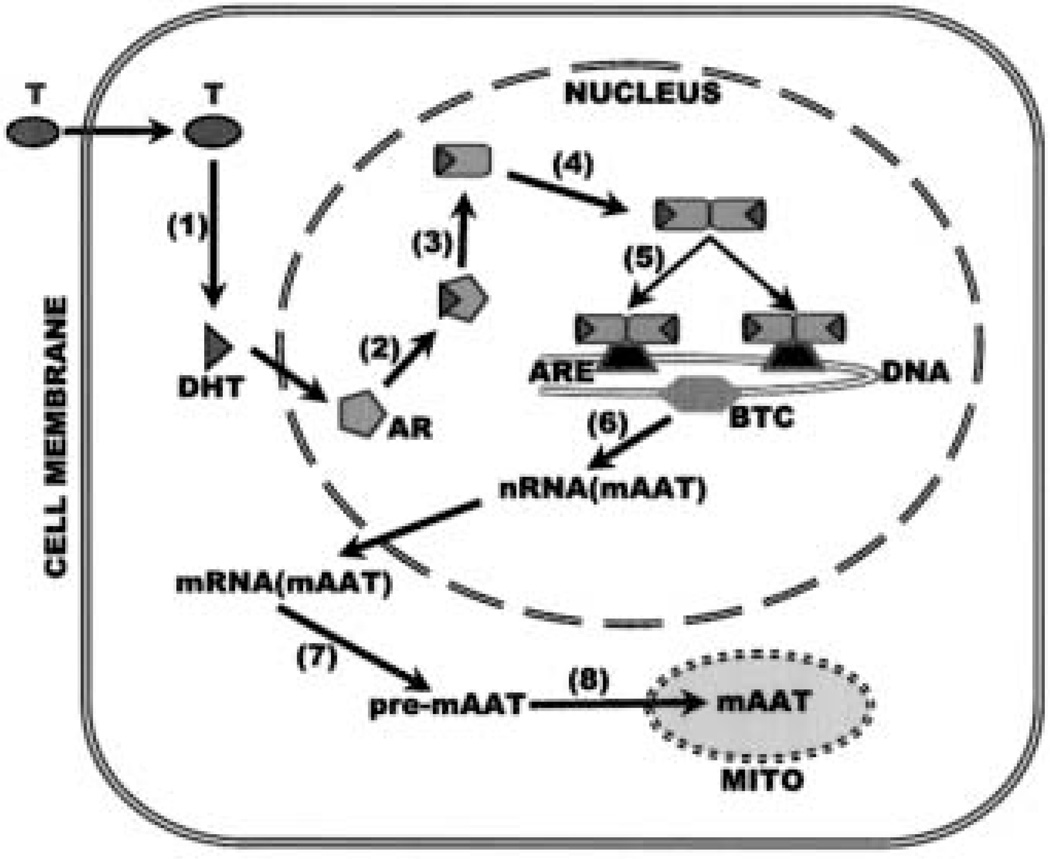

The regulation of mAAT, PDHE1a, and m-aconitase (metabolic genes) gene expression in prostate cells by testosterone is hormone- specific and cell-specific (to be discussed below). The discussion will focus on the mAAT gene since it is the most studied metabolic gene. Androgen action is mediated through an intracellular androgen receptor that exists in target cells. The androgen receptor is a member of a gene superfamily of transcription factors responsible for transduction of the actions of steroid hormones. Members of the superfamily include specific receptors for androgen, glucocorticoid, mineralocorticoid, progesterone, vitamin D, retinoic acid, estrogen and thyroid hormone. After ligand binding, the receptors undergo an activation process followed by binding to specific DNA sequences referred to as response elements. Fig. 2 shows the mechanism by which testosterone stimulates gene transcription, which in turn leads to the biosynthesis of mAAT as the model for the regulation of the metabolic genes.

Fig. 2.

The mechanism of testosterone regulation of the metabolic genes as represented by regulation of mAAT. (1) Testosterone enters the cell and is reduced to dihydrotestosterone (DHT); (2) DHT combines with androgen receptor (AR); (3) the DHT-AR complex undergoes a conformational change followed by (4) dimerization; the activated AR dimer binds to the androgen response elements (ARE 1 and 2) located in proximity of the basal transcription complex (BTC) of the mAAT gene; (6) transcription of mAAT is stimulated which leads to (7) the biosynthesis of pre-mAAT; (8) pre-mAAT is translocated to the mitochondria where it is processed to the active form of mAAT.

The sequence, structure, and functional operation of the androgen response element (ARE) in androgen-responsive genes have not been elucidated, and currently remains an enigma. There are similarities between the ARE and other steroid response elements, that is, the glucocorticoid (GRE), mineralocorticoid (MRE) and progesterone (PRE) response elements. The sequence for these steroid response elements is an imperfect palindrome consisting of two reverse-order hexamers separated by three nucleotides (GGTACAnnnTGTTCT). The consensus GRE sequence can also mediate the actions of other steroid hormones; consequently, the GRE has been referred to as a GRE/ARE/PRE. While a consensus sequence for the ARE based on binding studies has been reporter, Roche et al [39] concluded that specific-binding sites for the androgen receptor (AR) probably do not exist. Thus, the binding of ligand-activated receptors to their cognate response elements cannot account for specificity in differentiating androgen responses from other steroid hormones. On the other hand, a sequence that preferentially binds the androgen receptor has been reported [40]. However, recent studies of several androgen- responsive genes indicate that specificity of androgen action may be achieved by multiple-response elements in an androgen responsive region [41–44]. Response regions of this type appear to provide the necessary structure for modulation of transactivation in a hormone-and tissue-specific manner.

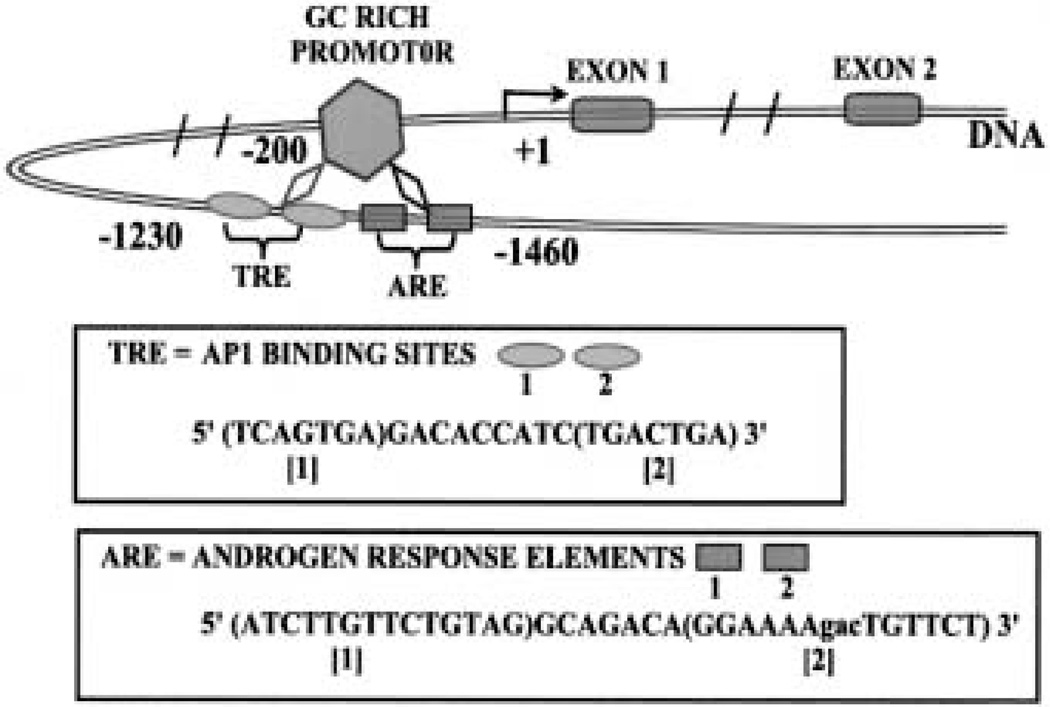

The androgen-regulated metabolic genes in prostate cells, as represented by mAAT, have promoters with properties typical of housekeeping genes (Fig. 3). The promoters lack a TATA and a CCAAT box, are rich in GC, and contain several SP1 binding sites. There are multiple transcription start sites. Utilization of the multiple sites occurs in the prostate and liver of intact rats. However, in castrated rats, the more distal transcription start sites are not used in the prostate cells, but are used in the liver cells. Testosterone treatment of castrated rats results in induction of transcription from four transcription start sites that were otherwise undetectable in castrated rats.

Fig. 3.

The hormone regulatory region of the mAAT gene.

The 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the mAAT gene (Fig. 3) contains two sequences that are closely related to the ARE consensus sequence. AREs are located at a distance of about – 1300 bp [19]. This allows for a DNA loop that brings the AREs in proximity of the promoter, thereby providing a functional regulatory structure. We have now cloned the 5′ UTRs of m-aconitase and PDH E1a. The 5′ flanking regions of these genes also contain multiple sequences that are similar to the mAAT gene AREs (unpublished information). Functional studies with cloned fragments of the PDHE1α; and m-aconitase genes are now under way in our laboratories, and we expect the androgen regulatory region of all the metabolic genes to exhibit high homology.

Prolactin regulation of metabolic genes

Prolactin regulation of cellular activities requires the existence of a plasma membrane prolactin receptor and an intracellular signal transduction process leading to the regulation of prolactin-responsive genes. Most studies reported relate to the well-known growth-promoting and differentiation effects (cytokine effects) of prolactin on various cell types. The cytokine effects of prolactin are mediated predominantly through the hormone-receptor initiation of a tyrosine kinase-associated pathway followed by cascading activation of immediate-early, intermediate and late-acting (final effector) genes (for reviews see [45, 46]). In most cases, the prolactin cytokine pathway does not generally involve or require the direct activation of PKC in the mediation of the cytokine effects.

In sharp contrast to the cytokine effects, prolactin regulation of metabolic genes in prostate cells does require the direct activation of PKC through direct hormone-receptor activation of the phospholipase-diacylglycerol pathway (Fig. 4) rather than a tyrosine- kinase cascading pathway. Metabolic genes are immediate- early genes as well as the final effector genes. Evidence for PKC mediation of prolactin regulation of the metabolic genes is derived from studies on mAAT gene regulation. Exposure of prostate cells to prolactin and to TPA rapidly (within 5 minutes) increases PKC activation, which is immediately followed by increased transcription of the mAAT gene [34, 35]. This stimulatory effect is abolished by PKC inhibitors gossypol and staurosporine and by TPA-induced down-regulation of PKC. Prolactin specifically activates two (PKCα and PKCε) of the eight PKC isoforms that were identified in prostate epithelial cells [47]. In addition, PKCε antisense abolishes prolactin stimulation of mAAT. Collectively, these relationships provide strong evidence that prolactin regulation of mAAT is mediated by the direct and rapid activation of PKCε.

Fig. 4.

The mechanism of prolactin regulation of the metabolic genes and citrate production in prostate cells as represented by regulation of mAAT. Prolactin combines with its receptor. The PRL-R complex couples to a plasma membrane component (?, unknown) which activates phospholipase c (PLC) leading to the formation of diacylglycerol (DG) and inositoltriphosphate (IP3) and the conversion of inactive PKC to membrane-bound active PKC. PKC phosphorylates cytosolic transcription factor (?, unknown) that leads to the formation of AP1 from existing protein (fos/jun). AP1 binds to its activation sites (that is, TRE = TPA response element) located in the regulatory region of the mAAT gene (see Fig. 3); mAAT gene transcription is increased leading to the biosynthesis of mAAT. Increased mAAT increases the production of OAA (oxalacetate) that is required for citrate synthesis.

The response element for PKC-regulated genes is referred to as a TPA response element (TRE) that contains AP1 binding sites. The 5′ flanking region of the mAAT gene (Fig. 3) contains five consensus- binding sequences for AP1 [35]. Computer analysis of the 5′ UTR of the rat PDHE1α, and the human m-aconitase genes also reveals TREs in these genes. Reporter gene studies with mAAT showed that a fragment of the mAAT gene containing two of these sequences was responsible for prolactin induction of expression [47]. We have also shown that prolactin, through PKCε activation, also activates a nuclear binding protein that appears to be AP1 [47]. In addition, the inhibition of PKCε expression by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides decreases PKCε activation and nuclear protein binding to the mAAT TRE in response to prolactin.

The connection between prolactin activation of PKCε and AP-1 formation that activates the TRE remains to be addressed and resolved. The cytosolic substrate (that is, transcription factor) for PKC and cascading events leading to the nuclear production of AP-1 has not been fully established. We have observed that prolactin treatment of PC-3 cells results in a rapid increase in the level of phosphorylated c-jun (unpublished results). This is consistent with the possibility that PKCε activation leads to the phosphorylation of JNK. The response of metabolic genes to prolactin is rapid, with alterations in the rates of transcription evident within 10 to 15 minutes following prolactin treatment. This response suggests that the metabolic genes are immediate early genes with induction times in the range of fos and jun induction in other cells. It is unlikely that the prolactin action on the expression of the metabolic genes requires and follows after prolactin induction of fos and jun expression. Thus, the available information leads us to propose (Fig. 4) that prolactin activates PKCε, which leads to AP-1 production from existing proteins (jun/fos), which in turn modulates the transcription of these genes leading to the biosynthesis of the corresponding enzymes.

These relationships of prolactin regulation of metabolism in prostate cells require that recent and contemporary views of the mechanisms of action of prolactin must be re-examined and modified.

The contemporary conclusion that prolactin effects are mediated predominantly via cascading tyrosine kinase-mediated pathways is no longer tenable. This description might be applicable to the cytokine effects of prolactin on many cell types; but it does not apply to the regulation of the metabolic genes in prostate cells. The view that “Prolactin and its close relatives are distinguished from other classical hormones by the generalization that they cause slow changes in cell differentiation and proliferation rather than rapid metabolic alterations” [48]; and that “the involvement of PKC in prolactin signal transmission seems remote” [49] are also untenable. One must recognize the difference between the “cytokine” and the “metabolic” effects of prolactin. The latter effect involves the direct intervention of the dia-cylglycerol-PKC signaling pathway. This does not preclude either the possible additional involvement of tyrosine kinase-activated components downstream from the prolactin-induced activation of PKC or the possibility that prolactin activation of tyrosine kinase cascade might result in downstream activation of PKC. It is important to note that studies with other mammalian cells have also demonstrated that some specific prolactin effects are mediated via PKC [50–52], but it is not clear that such effects are due to the direct and immediate prolactin activation of the diacylglycerol-PKC pathway independent of tyrosine kinase involvement. Prolactin reportedly activates tyrosine phosphorylation of Stat5a and Stat5b in epithelial cells of long-term rat prostate lobe organ cultures [53]. This likely reflects the cytokine effect of prolactin on prostate growth, as in other cells, which is mediated via the tyrosine kinase cascade, as compared with the PKC mediation of the metabolic genes.

Cell specificity of the hormone regulation of prostate metabolic genes

Testosterone and prolactin regulation of metabolic genes exhibit a high degree of cell specificity. It would be expected that cells lacking an androgen receptor or a prolactin receptor would not be responsive to any effects of these hormones; that is, these cells would be hormone-unresponsive. However, the effects of both hormones on the metabolic genes exhibit cell specificity, even among cells that are androgen-responsive and prolactin-responsive for many of the hormone actions [2,3, 23,27]. An example of this is the comparison between testosterone and prolactin regulation of m-aconitase in rat cells (Table 1). Both hormones regulate the gene expression and biosynthesis of m-aconitase in ventral prostate and lateral prostate cells, but neither hormone affects m-aconitase in dorsal prostate cells, kidney cells, or liver cells [27]. However, dorsal prostate cells, liver cells, and kidney cells do exhibit other responses to testosterone and/or prolactin. Specificity is more associated with the specialized function of net citrate production. Ventral and lateral prostate cells are citrate- producing cells, whereas dorsal prostate cells, kidney cells, and liver cells are not citrate-producing cells. Both mAAT and PDHE1a responses to testosterone and prolactin also exhibit the specificity for citrate-producing prostate cells. These metabolic genes are constitutively expressed in virtually all mammalian cells, but are only hormonally-responsive genes in the specialized citrate-producing epithelial cells. This raises the important question as to the mechanism that imparts hormone-responsiveness of the metabolic genes selectively in these prostate cells. In fact, the specificity is even more complex as represented by the opposite effects of both hormones on m-aconitase expression in ventral (increase) versus lateral (decrease) versus dorsal (no effect) prostate cells (Table 1). How does a hormone exhibit differing effects on a constitutively expressed gene in different cells of the same species? These are exciting and challenging issues that must be addressed and investigated.

Table 1.

Comparative effects of testosterone and prolactin regulation of citrate oxidation in rat prostate epithelial cells, kidney, and liver cells

| VP | LP | DP | K/L | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | T | P | T | P | T | P | T | |

| Citrate-producing cells | Yes | Yes | No | No | ||||

| m-aconase activity | + | + | − | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| m-aconase gene regulation | + | + | − | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Citrate oxidation | + | + | − | − | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

VP, ventral prostate; LP, lateral prostate; DP, dorsal prostate; K, kidney; L, liver; +, stimulation; −, inhibition; 0, no effect; P, prolactin; T, testosterone.

Other metabolic reactions regulated by testosterone and prolactin

Hormonal regulation of the unique function and capability of net citrate production imposes and requires the implementation and coordination of a number of metabolic activities. The regulation of the key enzymes described above provides the direct control of citrate synthesis and citrate oxidation. Additional metabolic activities are also recruited in the process of net citrate production, which are deserving of some mention in this review.

Glucose, via pyruvate oxidation, is the source of acetyl CoA that is required for citrate synthesis. Therefore, the hormonal stimulation of citrate production must be accompanied by an increase in glucose oxidation to pyruvate. There is evidence that testosterone does indeed increase the utilization of glucose and production of pyruvate in prostate cells [20, 54], although the mechanism has not been established. Unfortunately, no information exists regarding such a role for prolactin.

There must also be a continual supply of aspartate as a source of OAA for high citrate production. The prostate cells contain a unique plasma membrane high-affinity aspartate transporter that allows for the effective extraction and uptake of aspartate from the circulation [55, 56]. Consistent with the stimulatory effect on net citrate production, both testosterone and prolactin increase transporter activity, apparently through regulation of the transporter gene [56,57].

Prostate cells accumulate the highest levels of zinc of any cells in the body. The accumulation of zinc inhibits m-aconitase activity and citrate oxidation [8]. Both testosterone and prolactin regulate the uptake and accumulation of zinc specifically in citrate-producing prostate cells [58]. The ability to accumulate zinc is partly due to the presence of a zinc uptake transporter in these prostate cells [59]. The transporter is regulated by prolactin and testosterone, which regulate the accumulation of zinc. This provides another mechanism for the hormonal control of citrate oxidation and net citrate production.

These relationships bring to focus the multifaceted and coordinated metabolic activities that must be involved in the hormonal regulation of prostate citrate production. This hormonal control requires the regulation of selective metabolic genes associated with enzyme and transport activities that are essential to the process of citrate production. How these hormone-responsive genes become selected and coordinated is a fascinating relationship awaiting resolution.

Acknowledgement

This review and the studies of LCC and RBF reported herein were supported by NIH research grants CA71207, DK28015, DK42839, CA79903.

Rereferences

- 1.Costello LC, Franklin RB. Citrate metabolism of normal and malignant prostate epithelial cells. Urol. 1997;50:3–12. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Franklin RB, Costello LC. Intermediary energy metabolism of normal and malignant prostate epithelial cells. In: Naz RK, editor. Prostate: Basic and clinical aspects. New York: CRC Press; 1997. pp. 115–150. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costello LC, Franklin RB. The novel role of zinc in the intermediary metabolism of prostate epitelial cells and its implications in prostate malignancy. Prostate. 1998;35:285–296. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19980601)35:4<285::aid-pros8>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costello LC, Franklin RB. The intermediary metabolism of the prostate: A key to understanding the pathogenesis and progression of prostate malignancy. Oncology. 2000;59:269–282. doi: 10.1159/000012183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Costello LC, Franklin RB. Concepts of citrate production and secretion by prostate. 2. Hormone relationships in normal and neoplastic prostate. Prostate. 1991;19:181–205. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990190302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costello LC, Franklin RB. Effect of prolactin on the prostate. Prostate. 1994;24:162–166. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990240311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costello LC, Franklin RB. Aconitase activity, citrate oxidation and zinc inhibition in rat ventral prostate. Enzyme. 1982;26:281–287. doi: 10.1159/000459195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costello LC, Liu Y, Franklin RB, Kennedy MC. Zinc inhibition of mitochondrial aconitase and its importance in citrate metabolism of prostate epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28875–28881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.28875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costello LC, Franklin RB, Kennedy MC. Zinc causes a shift toward citrate at equilibrium of the m-aconitase reaction of prostate mitochondria. J Inorg Biochem. 2000;78:161–165. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(99)00225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humphrey GF, Mann R. Studies on the metabolism of semen. Citric acid in semen. Biochem J. 1949;44:97–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costello LC, Littleton GK, Franklin RB. Endocrine Control in Neoplasia. New York: Raven Press; 1978. Citrate and related intermediary metabolism in normal and neoplastic prostate; pp. 304–314. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costello LC, Franklin RB. Concepts of citrate production and secretion by prostate. 1. Metabolic relationships. Prostate. 1991;18:25–46. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990180104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Franklin RB, Brandly RL, Costello LC. Mitochondrial aspartate, aminotransferase and the effect of testosterone on citrate production in rat ventral prostate. J Urol. 1982;127:798–802. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)54052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franklin RB, Brandly RL, Costello LC. Effect of inhibitors of RNA and protein synthesis on mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase response to testosterone in rat ventral prostate. Prostate. 1982;3:637–642. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990030614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franklin RB, Kahng MW, Akuffo V, Costello LC. The effect of testosterone on citrate synthesis and citrate oxidation and a proposed mechanism for regulation of net citrate production in prostate. Horm Metab Res. 1986;18:177–181. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1012264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costello LC, Akuffo V, Franklin RB. Testosterone stimulates net citrate production from aspartate by prostate epithelial cells. Horm Metab Res. 1988;20:252–253. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1010807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Franklin RB, Qian K, Costello LC. Regulation of aspartate aminotransferase messenger RNA level by testosterone. J Steroid Biochem. 1990;35:569–574. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(90)90200-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qian K, Franklin RB, Costello LC. Testosterone regulates mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase gene expression and mRNA stability in prostate. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1993;44:13–19. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(93)90146-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Juang HH, Costello LC, Franklin RB. Androgen modulation of multiple transcription start sites of the mAAT gene in rat prostate. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12629–12634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.21.12629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harkonen PL. Androgenic control of glycolysis, the pentose cycle and pyruvate dehydrogenase in the rat ventral prostate. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1981;14:1075–1084. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(81)90219-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Costello LC, Franklin RB. Testosterone regulates pyruvate dehydrogenase activity of prostate mitochondria. Horm Metab Res. 1993;25:268–270. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1002094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costello LC, Franklin RB, Liu Y. Testosterone regulates pyruvate dehydrogenase E1α in prostate. Endocrine J. 1994;2:147–151. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costello LC, Liu Y, Zou J, Franklin RB. The pyruvate dehydrogenase E1α gene is regulated by testosterone and prolactin in prostate epithelial cells. Endocrine Res. 2000;26:23–29. doi: 10.1080/07435800009040143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Costello LC, Liu Y, Franklin RB. Testosterone stimulates the biosynthesis of m-aconitase in prostate epithelial cells. Cell Mol Endocrinol. 1995;112:45–51. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(95)03582-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franklin RB, Juang HH, Zou J, Costello LC. Regulation of citrate metabolism by androgen in human prostate carcinoma cells. Endocrine J. 1995;3:603–607. doi: 10.1007/BF02953026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costello LC, Liu Y, Franklin RB. Testosterone and prolactin stimulation of m-aconitase in pig prostate epithelial cells. Urology. 1996;48:654–659. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(96)00217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costello LC, Liu Y, Zou J, Franklin RB. Mitochondrial aconitase gene expression is regulated by testosterone and prolactin in prostate epithelial cells. Prostate. 2000;42:196–202. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(20000215)42:3<196::aid-pros5>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rui H, Purvis K. Hormonal control of prostate function. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 1988;107:32–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grayhack JT, Lebowitz A. Effect of prolactin on citric acid of lateral lobe of prostate of Sprague-Dawley rats. Invest Urol. 1967;5:7–94. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grayhack JT. Effect of testosterone, estradiol administration on citric acid and fructose content of the rat prostate. Endocrinol. 1965;77:1068–1074. doi: 10.1210/endo-77-6-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rui H, Purvis K. Independent control of citrate production and ornithine decarboxylase by prolactin in the lateral lobe of the rat. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1987;52:91–95. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(87)90101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Franklin RB, Costello LC. Prolactin directly stimulates citrate production and mAAT of prostate epithelial cells. Prostate. 1990;17:13–18. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990170103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arunakaran J, Aruldhas MM, Govindarajulu P. Effect of prolactin and androgens on the prostate of bonnet monkeys, macaca radiata: I. nucleic acids phosphatases and citric acid. Prostate. 1987;10:265–273. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990100309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franklin RB, Zou J, Gorski E, Yang YH, Costello LC. Prolactin regulation of mAAT and PKC in human prostate cancer cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1997;127:19–25. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(96)03972-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gorski E, Zou J, Costello LC, Franklin RB. Protein kinase C mediates prolactin regulation of mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase gene expression in prostate cells. Molecular Urol. 1999;3:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Franklin RB, Ekiko DB, Costello LC. Prolactin stimulates transcription of aspartate aminotransferase in prostate cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1992;90:27–32. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(92)90097-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Costello LC, Franklin RB, Liu Y. Prolactin specifically increases PDH E1α in rat lateral prostate epithelial cells. Prostate. 1995;26:189–193. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990260404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Costello LC, Franklin RB. Prolactin specifically regulates citrate oxidation and m-aconitase of prostate epithelial cells. Metabolism. 1996;45:442–449. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(96)90217-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roche PJ, Hoare SE, Parker MG. A consensus DNA binding site for the androgen receptor. Mol Endocrinol. 1992;6:2229–2235. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.12.1491700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhou Z, Corden JL, Brown TR. Identification and characterization of a novel androgen response element composed of a direct repeat. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:8227–8235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.13.8227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cleutjens KB, van Eekelen CC, van der Korput HA, Brinkmann AO, Trapman J. Two androgen response regions cooperate in steroid hormone regulated activity of the prostate specific antigen promoter. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6379–6388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dai JL, Burnstein KL. Two androgen response elements in the androgen receptor coding region are required for cell-specific up-regulation of receptor messenger RNA. Mol Endocrinol. 1996;10:1582–1594. doi: 10.1210/mend.10.12.8961268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Claessens F, Alen P, Devos A, Peeters B, Verhoeven G, Rombauts W. The androgen-specific probasin response element 2interacts differentially with androgen and glucocorticoid receptors. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19013–19016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Claessens F, Verrijdt G, Schoenmakers E, Haelens A, Peeters B, Verhoeven G, Rombauts W. Selective DNA binding by the androgen receptor as a mechanism for hormone-specific gene regulation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;76:23–30. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(00)00154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Larrea F, Sanchez-Gonzalez S, Mendez I, Garcia-Becerra R, Cabrera V, Ulloa-Aguirre A. G protein-coupled receptors as targets for prolactin actions. Arch Med Res. 1999;30:532–543. doi: 10.1016/s0188-0128(99)00056-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bole-Feysot C, Goffin V, Edery M, Binart N. Prolactin and its receptor. Actions, signal transduction pathways and phenotypes observed in PRL receptor knockout mice. Endocrine Rev. 1998;19:225–268. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.3.0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franklin RB, Zou J, Ma J, Costello LC. Protein kinase C alpha, epsilon and AP-1 mediate prolactin regulation of mitochondrial aspartate aminotransferase expression in the rat lateral prostate. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2000;170:153–162. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(00)00321-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu Y-H, Horseman ND. Nuclear proteins and prolactin-induced annesin Icp35 gene transcription. Mol Endocrinol. 1992;6:375–383. doi: 10.1210/mend.6.3.1533897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carey GB, Liberti JP. Stimulation of receptor-associated kinase, tyrosine kinase, and MAP kinase is required for prolactin mediated macromolecular biosynthesis and mitogenesis in Nb2lymphoma. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;316:179–189. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1995.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crowe PD, Buckley AR, Zorn NE, Rui H. Prolactin activates protein kinase C and stimulates growth-related gene expression in rat liver. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1991;79:29–35. doi: 10.1016/0303-7207(91)90092-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ciereszko RE, Petroff BK, Ottobre AC, Guan Z, Stokes BT, Ottobre JS. Assessment of the mechanism by which prolactin simulates progesterone production by early corpora lutea of pigs. J Endocrinol. 1998;159:201–209. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1590201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peters CA, Maizels ET, Robertson MC, Shiu RPC, Soloff MS, Hunzicker-Dunn M. Induction of relaxin messenger RNA expression in response to prolactin receptor activation requires protein kinase C delta signaling. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:576–590. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.4.0455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahonen TJ, Harkonen PL, Rui H, Nevaleinen MT. PRL signaling in the epithelial cell compartment of rat prostate maintained as long-term organ cultures in vitro. Endocrinol. 2002;143:228–238. doi: 10.1210/endo.143.1.8576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harkonen PL, Isoltalo A, Santti R. Studies on the mechanism of testosterone action on glucose metabolism in the rat ventral prostate. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1975;6:1405–1413. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(75)90077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Franklin RB, Lao L, Costello LC. Evidence for two aspartate transport systems in prostate epithelial cells. Prostate. 1990;16:137–146. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990160205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lao L, Franklin RB, Costello LC. A high affinity L-aspartate transporter in prostate epithelial cells which is regulated by testosterone. Prostate. 1993;22:53–63. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990220108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lao L. Characteristics and regulation of aspartate transport systems in rat ventral prostate epithelial cells. In: Franklin RB, Costello LC, editors. Ph.D. Thesis Dissertation. University of Maryland; 1992. p. 144. (thesis advisors). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu Y, Costello LC, Franklin RB. Prolactin and testosterone regulation of mitochondrial zinc in prostate epithelial cells. Prostate. 1997;30:26–32. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19970101)30:1<26::aid-pros4>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Costello LC, Liu Y, Zou J, Franklin RB. Evidence for a zinc uptake transporter in human prostate cancer cells which is regulated by prolactin and testosterone. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17499–17504. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]