Abstract

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a pervasive, aging-related neurodegenerative disease whose cardinal motor symptoms reflect the loss of a small group of neurons – dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc)1. Mitochondrial oxidant stress is widely viewed as responsible for this loss2, but why these particular neurons should be stressed is a mystery. Using transgenic mice that expressed a redox-sensitive variant of green fluorescent protein targeted to the mitochondrial matrix, it was discovered that the unusual engagement of plasma membrane L-type calcium channels during normal autonomous pacemaking created an oxidant stress that was specific to vulnerable SNc dopaminergic neurons. This stress engaged defenses that induced transient, mild mitochondrial depolarization or uncoupling. The mild uncoupling was not affected by deletion of cyclophilin D, a component of the permeability transition pore, but was attenuated by genipin and purine nucleotides, antagonists of cloned uncoupling proteins. Knocking out DJ-1, a gene associated with an early onset form of PD, down-regulated the expression of two uncoupling proteins (UCP4, 5), compromised calcium-induced uncoupling and increased oxidation of matrix proteins specifically in SNc dopaminergic neurons. Because drugs approved for human use can antagonize calcium entry through L-type channels, these results point to a novel neuroprotective strategy for both idiopathic and familial forms of PD.

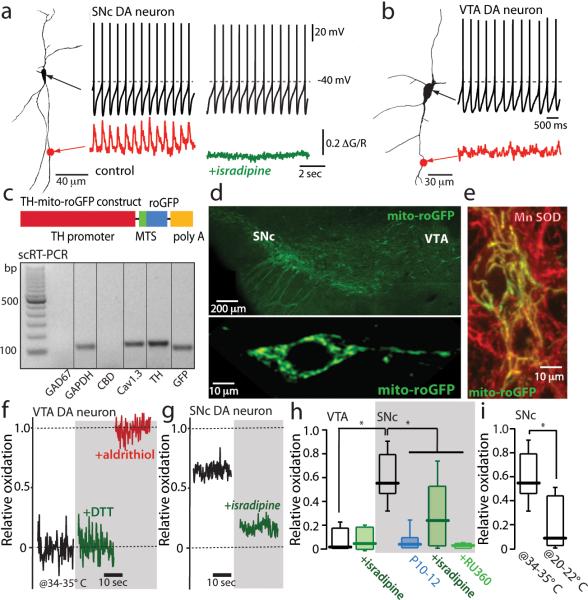

Calcium entry through L-type channels in SNc dopaminergic neurons occurs throughout the pacemaking cycle 3,4, contrasting them with neighboring dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) that are much less affected in PD 5(Fig. 1a,b). Although prominent, this influx is not necessary for pacemaking, as treatment with the dihydropyridine L-type channel antagonist isradipine eliminates cytosolic calcium oscillations, but leaves pacemaking intact 6 (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1. Calcium influx through L-type calcium channels during pacemaking increases mitochondrial oxidant stress in SNc dopaminergic neurons.

(a) Somatic whole cell recording from a SNc dopaminergic neuron (shown to the left as a projection image) in pacemaking mode. At the bottom of the panel, a 2PLSM measurement of dendritic Fluo-4 fluorescence (red trace) is shown. To the right are shown a similar set of measurements after application of isradipine; note the absence of a change in pacemaking rate but the loss of dendritic calcium transients (green trace)(n=10 neurons, P<0.05). (b) A similar set of measurements in a VTA dopaminergic neuron; these neurons consistently lacked dendritic calcium oscillations (n=6 neurons). (c) Schematic of the TH-mito-roGFP construct. Below the construct, single-cell RT-PCR analysis of mito-roGFP expressing SNc dopaminergic neuron showing expression of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) and Cav1.3 calcium channel mRNA, but not calbindin (CBD) or GAD67 mRNA; similar results were obtained in all 5 neurons examined. (d) Top, a low magnification image of the mesencephalon of a transgenic TH-mito-roGFP mouse showing expression in SNc and VTA neurons. Bottom, a higher magnification image of a SNc neuron showing cytoplasmic but not nuclear labeling. (e) Overlay of Mn-SOD immunostaining (red) showing colocalization with mito-roGFP in cultured roGFP SNc neurons. (f) Mito-roGFP measurements from a VTA neuron; before (control, black trace), and after application of dithiothreitol (DTT) (green trace), and aldrithiol (red trace). Relative oxidation is plotted as described in Methods. (g) Mito-roGFP measurements from a SNc dopaminergic neuron (black trace) revealed a higher basal oxidation; treatment with isradipine diminished mitochondrial oxidation (green trace). (h) Left, box-plots summarizing mean redox measurements in control (n=9) and isradipine treated (n=5) VTA dopaminergic neurons; in control (n=14), isradipine (n=9) and Ru360 (n=8) treated SNc dopaminergic neurons; SNc neurons were significantly more oxidized than VTA neurons (P<0.05); both isradipine and Ru360 significantly reduced oxidation (P<0.05). SNc dopaminergic neurons from young mito-roGFP mice (P10-P12) were consistently less oxidized than adult neurons (P<0.05, n=8). (i) Box plots summarizing mean mito-roGFP measurements in SNc dopaminergic neurons in brain slices held at near physiological temperature (34-35°C) (n=14) and at room temperature (20-22°C) (n=5); oxidation was significantly less at room temperature (P<0.05). Statistical significance in all plots is shown by an asterisk and determined using a non-parametric test for comparing multiple groups (Kruskal-Wallis ANOVA with Dunnet's post hoc test).

Calcium entry during pacemaking comes at a metabolic cost, as it must be extruded by adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-dependent processes. This demand is met primarily by mitochondria through oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). Superoxide and reactive oxygen species (ROS) are by-products of OXPHOS, raising the possibility that calcium entry creates mitochondrial oxidant stress. To determine whether this was the case, transgenic mice expressing a redox-sensitive variant of green fluorescent protein (roGFP) with a mitochondrial matrix targeting sequence (mito-roGFP) were generated 7. To limit expression to monoaminergic neurons, mito-roGFP was expressed under control of the tyrosine hydroxylase promoter (Fig. 1c). Dopaminergic neurons in the SNc and the adjacent VTA from these mice robustly expressed mito-roGFP that colocalized with mitochondrial markers (Fig. 1c-e; Supplementary Fig. 1), providing a reversible, quantitative means of monitoring oxidation of mitochondrial matrix proteins. Because the expression of mito-roGFP was restricted to a small set of neurons, it was possible to monitor mitochondrial redox state in individual neurons deep in brain slices from young adult mice using two photon laser scanning microscopy (2PLSM).

In VTA dopaminergic neurons, the basal oxidation of mito-roGFP was very low (Fig.1f). In contrast, the oxidation of mito-roGFP was significantly higher in neighboring SNc dopaminergic neurons (Fig. 1g,h). In juvenile SNc dopaminergic neurons, where pacemaking is similar to that of VTA neurons, mitochondrial oxidant stress also was low (Fig. 1h). To verify this stress was not an artifact of brain slicing, a second transgenic mouse was generated that expressed mito-roGFP under the control of the cytomegalovirus promoter, yielding robust neuronal expression in the cerebral cortex, striatum and hippocampus. In brain slices from these mice, principal neurons in each of these regions were devoid of any significant mitochondrial oxidation (Supplementary Fig. 2), demonstrating that slicing per se did not create oxidant stress.

What did contribute significantly to the mitochondrial oxidant stress was calcium influx through plasma membrane L-type channels. Antagonizing L-type channels dramatically lowered the extent of mito-roGFP oxidation (Fig.1g,h), as did slowing pacemaking by cooling (Fig. 1i). L-type channel antagonists had no effect on the oxidation of matrix proteins in neighboring VTA dopaminergic neurons (Fig. 1h). Blocking calcium entry into mitochondria from the cytoplasm with Ru360 8 diminished roGFP oxidation (without affecting pacemaking) (Fig. 1h), suggesting that it helped to drive OXPHOS 9.

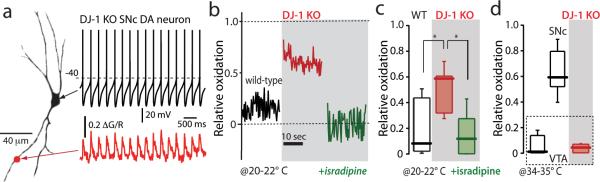

Loss-of-function mutations in DJ-1 are linked to an autosomal recessive, early onset form of PD 10. Although DJ-1 is not an anti-oxidant enzyme itself, it is redox-sensitive and participates in signaling cascades made active by mitochondrial superoxide generation. To examine its role in SNc dopaminergic neurons, DJ-1 knockout mice were crossed with the TH-mito-roGFP mice. SNc dopaminergic neurons from these mice had normal pacemaking and oscillations in intracellular calcium concentration (Fig. 2a). However, basal mito-roGFP oxidation was nearly complete at physiological temperatures in these neurons, so cells were re-examined at a lower temperature. These studies confirmed the robust difference in oxidation between wild type and DJ-1 knockout neurons seen at higher temperature (Fig. 2b,c). This difference was virtually abolished by antagonism of L-type calcium channels (Fig. 2b,c). In contrast, the mitochondria in neighboring VTA dopaminergic neurons were unaffected by DJ-1 deletion (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2. Oxidant stress is elevated in SNc dopaminergic neurons from DJ-1 knockout mice.

(a) Somatic whole cell recording from a SNc dopaminergic neuron in a brain slice from a DJ-1 knockout mouse, showing normal pacemaking (top) and intracellular calcium oscillations (bottom); similar results were obtained in all five neurons examined. (b) Mitochondrial mito-roGFP oxidation was higher (red trace) than in control SNc dopaminergic neurons (black trace); isradipine pretreatment normalized oxidation of mito-roGFP (green trace); experiments were done at 20-22 °C. (c) Box plot summarizing mean mito-roGFP measurements in wild-type SNc neurons (n=9), DJ-1 knockout SNc neurons (n=6) and DJ-1 knockout neurons after isradipine pretreatment (n=7); differences between wild-type and DJ-1 knockout were significant (P<0.05), as were differences between knockouts with and without isradipine treatment (P<0.05). (d) Box plot summarizing mean mito-roGFP measurements from wild-type VTA dopaminergic neurons (n=9), wild-type SNc dopaminergic neurons (n=14) and DJ-1 knockout VTA dopaminergic neurons (red box) (n=4) at 34-35 °C. VTA dopaminergic neurons were unaffected by DJ-1 deletion (P>0.05).

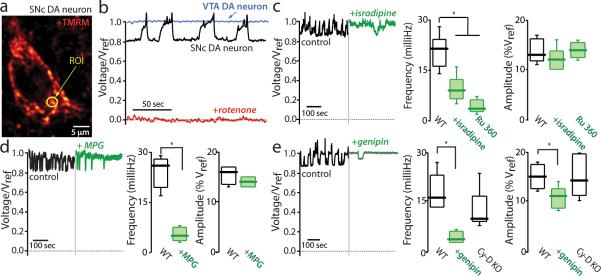

A clue about the role played by DJ-1 in attenuating mitochondrial oxidant stress came from measurements of the inner mitochondrial membrane (IMM) potential with the cationic dye tetramethyl rhodamine methylester (TMRM) (Fig. 3a; Supplementary movie). In VTA dopaminergic neurons, TMRM fluorescence was robust and stable for long periods (Fig. 3b). In contrast, mitochondrial TMRM fluorescence in neighboring SNc dopaminergic neurons repeatedly fell and then rose back to peak values, indicating that mitochondria were transiently depolarizing (Fig. 3b; Supplementary movie). This ‘flickering’ was stable for long periods (>60 minutes) and peculiar to SNc dopaminergic neurons, arguing that it was not a product of the preparation (Supplementary Fig. 2). Using a Nernst equation relating IMM potential to the ratio of mitochondrial to nuclear TMRM fluorescence 11, it appeared that the flickering in mitochondrial potential was modest, corresponding to a IMM depolarization of only 20-30 mV.

Figure 3. Mitochondrial flickering is dependent on superoxide production and recruitment of mitochondrial uncoupling proteins.

(a) SNc dopaminergic neuron in a brain slice incubated with tetramethyl rhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) to label mitochondria; a region of interest (ROI) from which fluorescence measurements were taken is shown (yellow circle). (b) Representative fluorescence time-series from a SNc dopaminergic neuron (black trace) before and after rotenone (red trace) application; similar results were seen in all cells examined (n>20). For comparison, a time series from a typical VTA dopaminergic neuron is shown (blue trace) (n=10). (c) Left, TMRM fluorescence measurements before (black trace) and after bath application of isradipine (green trace); Right, box plots summarizing the mean frequency of flickering in control cells before and after application of isradipine (n=5) or Ru360 (n=6), both significantly slowed flickering frequency (P<0.05); box plots summarizing the mean amplitude of the relative voltage change inferred from the fluorescence measurement; the amplitudes were similar in all conditions (P>0.05). (d) Left, fluorescence time series before and after bath application of MPG (green trace); Right, box plots summarizing mean frequency and amplitude measurements (n=5); MPG significantly reduced the frequency (P<0.05) but not the amplitude (P>0.05) of flickering. (e) Left, fluorescence time series before and after application of genipin (green trace); genipin decreased the frequency and amplitude of the flickering; Right, box plots summarizing mean amplitude and frequency measurements before and after genipin (n=5); genipin significantly decreased both parameters (P<0.05). Both measurements were normal in cyclophilin D knockouts (n=10; P>0.05).

Antagonizing plasma membrane L-type calcium channels with isradipine dramatically reduced the rate of flickering (Fig. 3c; Supplemental movie), as did blocking calcium entry into the mitochondria with Ru360 (Fig. 3c). However, flickering was also attenuated by scavenging ROS with the cell-permeable antioxidant N-(2-mercaptopropionyl)-glycine (MPG) (Fig. 3d), suggesting that oxidant stress created by calcium entry, rather than calcium per se, was responsible for the mitochondrial flickering. This inference was consistent with the fact that mitochondrial flickering was roughly ten times slower than the oscillation in cytosolic calcium concentration (c.f., Figs. 1a, 3b).

Superoxide generation is known to trigger the opening of two types of ion channel that depolarize the IMM. One of these is the permeability transition pore (PTP) 12. However, TMRM flickering was normal in SNc dopaminergic neurons lacking cyclophilin D – a key modulator of the PTP – (Fig. 3e), arguing against a role for the PTP. Cyclosporin A, which is known to antagonize the PTP, decreased IMM flickering, but it also slowed or stopped pacemaking (and calcium influx), making it an unreliable diagnostic tool.

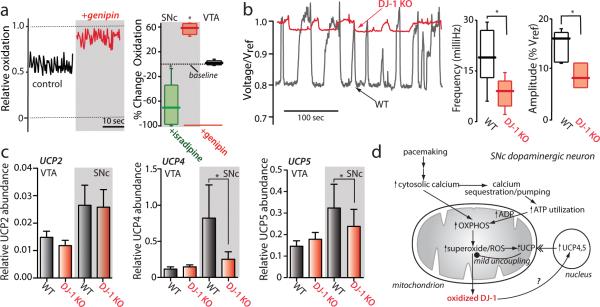

Uncoupling proteins (UCPs) are another class of mitochondrial ion channel whose open probability is increased by superoxide 13. UCP opening decreases the IMM potential modestly 14, making it a plausible mediator of the drop in IMM potential inferred from the TMRM measurements. Five UCPs have been cloned, three of which are robustly expressed in the SNc (UCP2,4,5) 15. Application of the UCP antagonist genipin 16 significantly decreased the frequency and amplitude of mitochondrial flickering (Fig. 3e), as did dialyzing neurons with adenosine triphosphate (Supplementary Fig. 3), providing support for UCP mediation 17. The modest depolarization brought about by UCP activation is thought to diminish superoxide generation without significantly compromising ATP production, creating a protective, negative feedback system to complement enzymatic defenses against ROS 17,18. If this were the case, blocking UCPs with genipin should cause superoxide levels and oxidation of mitochondrial proteins to rise. Indeed, genipin significantly elevated oxidation of mito-roGFP in SNc dopaminergic neurons, whereas it had no effect on mitochondrial oxidation in VTA dopaminergic neurons, where the UCP defense was not engaged (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4. Loss of DJ-1 attenuated UCP-dependent flickering in mitochondrial membrane potential.

(a) Left, mito-roGFP measurements in a SNc dopaminergic neuron (as in Figure 1) before and after application of genipin (red trace). Right, box plots summarizing mean mito-roGFP measurements following isradipine application (green box) (n=9) or genipin (red box) (n=6) to SNc dopaminergic neurons; isradipine significantly decreased oxidation, whereas genipin increased oxidation (P<0.05). Also show is a box plot of mito-roGFP measurements from VTA dopaminergic neurons following genipin; genipin had no effect on these measurements (n=5, P>0.05). (b) Left, TMRM fluorescence measurement from a wild-type SNc dopaminergic neuron (black trace) and a DJ-1 knockout (red trace). Right, box plots of mean frequency and amplitude data from wild-type (n=21) and DJ-1 knockout neurons (n=7); both amplitude and frequency of flickering were decreased in DJ-1 knockouts (P<0.05). (c) Quantitative PCR analysis of UCP expression in DJ-1 knockout mice: UCP2 mRNA abundance (relative to GAPDH) was not significantly altered in VTA and SNc (P>0.05, n=9). To the right, bar graphs plot the abundance of UCP4 and UCP5 mRNAs, normalized by that of UCP2 in each sample. The relative abundance of UCP4 and UCP5 mRNA was decreased in the SNc of DJ-1 knockout mice (P<0.05, n=9). UCP4 mRNA abundance was higher in VTA from DJ-1 knockout mice (P<0.05, n=9), while UCP5 mRNA was unchanged. (d) Schematic summary of the results presented linking calcium entry through L-type channels during pacemaking with elevated mitochondrial oxidant stress and opening of UCPs. The model also proposes that oxidized DJ-1 translocates to the nucleus and increases the transcription of UCP4 and UCP5, leading to increased UCP protein in the IMM.

In DJ-1 null SNc dopaminergic neurons, mitochondrial flickering was reduced in amplitude and frequency, suggesting that their UCP defenses were compromised (Fig. 4b). Because DJ-1 is largely found outside mitochondria, it is not likely to play a direct role in gating UCPs 19. Another function of DJ-1 is to up-regulate the expression of anti-oxidant proteins in response to stress 10,20,21. Quantitative analysis of mRNA from the SNc of DJ-1 knockouts revealed normal levels of UCP2 mRNA (Fig. 4c), suggesting that UCP2 was not a participant in flickering – a conclusion consistent with examination of neurons from UCP2 knockout mice (data not shown). In contrast, UCP4 and UCP5 mRNAs were down regulated in the SNc of DJ-1 knockouts (Fig. 4c), bringing expression levels down to those found in the unstressed VTA. UCP expression levels in the cerebral cortex, striatum and hippocampus were largely unchanged by DJ-1 deletion (Supplementary Fig. 4). The expression of mRNAs for the antioxidant enzymes manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD), glutathione peroxidase and catalase also were largely unchanged in the SNc of DJ-1 knockouts, but immunoreactivity for MnSOD protein in situ was higher (Supplementary Fig. 5). These data suggest that the elevation in mitochondrial oxidant stress in SNc dopaminergic neurons lacking DJ-1 was not due to lowered expression of anti-oxidant enzymes, but rather to diminished UCP4 and UCP5 expression, blunting UCP-mediated mitochondrial uncoupling in response to calcium-induced stress.

Collectively, our studies demonstrate that in mature SNc dopaminergic neurons there is a basal mitochondrial oxidant stress. This oxidant stress was not a consequence of old age, pathology or the experimental preparation, but rather a consequence of a neuronal design that engages L-type calcium channels during autonomous pacemaking. Mitochondrial oxidant stress of this sort has long been thought to be central to the etiology of PD 2. However, there has been no explanation for why this stress should be greater in a small population of mesencephalic neurons. Our results fill this gap (Fig. 4d). The basal oxidant stress in SNc dopaminergic neurons was amplified by deletion of DJ-1, a gene associated with an early onset, familial form of PD. In agreement with its putative role in regulating oxidant defenses 10, deletion of DJ-1 diminished UCP5 and UCP4 mRNA in the SNc and compromised mitochondrial uncoupling in response to oxidant stress. Although the hypothesis that the effects of DJ-1 deletion on SNc dopaminergic neurons are mediated by loss of UCP expression remains to be definitively tested, this scenario provides an example of how a mutation in a widely expressed gene might manifest itself only in sub-population of neurons. Our data also provide a potential explanation for the unusual accumulation of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations with age in SNc dopaminergic neurons 22,23. These mutations, which are attributable to accumulated superoxide exposure, diminish mitochondrial competence and promote phenotypic decline, proteostatic impairments and death 24,25.

Because the mitochondrial oxidant stress in SNc dopaminergic neurons was dramatically attenuated by exposure to dihydropyridines, our results also point to a potential neuroprotective strategy in both idiopathic and familial PD. Dihydropyridines have a long history of safe use in humans and have good pharmacokinetic properties, including the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier 26. Recent epidemiological studies support their potential value, showing that dihydropyridine use substantially reduces the risk of PD 27,28.

Methods Summary

Midbrain slices were obtained from mice between postnatal ages 21 and 30. Mice were handled according to guidelines established by the Northwestern University Animal Care and Use Committee, the National Institutes of Health and the Society for Neuroscience. Midbrain slices were visualized using infrared-differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) video microscopy system (for patch clamp recording) and imaged with 2PLSM to measure calcium transients, mitochondrial membrane potential using TMRM dye, or mito-roGFP signal. SNc or VTA neurons were filled with Alexa594 and Fluo-4 and calcium transients were imaged as described previously 6. Mitochondrial membrane potential was calculated using a Nernst equation describing the distribution of TMRM 11. Transgenic mice were generated by conventional approaches with a roGFP2 construct containing the TH promoter and a matrix mitochondria-targeting sequence. Relative oxidation of mito-roGFP was determined from fluorescence measurements after fully reducing mitochondria with dithiothreitol and then fully oxidizing with aldrithiol. Since the calibrated signal becomes independent of absolute expression level of mito-roGFP, this strategy allows cell-to-cell comparisons. Results in the main body of the paper were derived from a single line of mice showing strong mito-roGFP expression. In the presence of a strong reducing agent as an estimate of roGFP concentration, we inferred that there was not a significant difference in the expression level between SNc and VTA neurons (Supplementary Figure 7). The oxidation state of mitochondria was also verified in a second line of mice having lower mito-roGFP expression levels (Supplementary Figure 7) and in cultured cells expressing mito-roGFP (Supplementary Figure 6). Single-cell reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (scRT-PCR) has been described previously 4. Relative gene expression of UCPs was performed by reverse transcriptase reaction followed by quantitative PCR analysis. Mn-SOD immunostaining used standard approaches. Sample “n” represents number of mice. Statistical analysis was performed with non-parametric test with threshold for significance less than 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the technical help of Philip Hockberger, Nicholas Schwarz, Sasha Ulrich, Yu Chen, Dilyan Dryanovski and Karen Saporito. We acknowledge the gifts of DJ-1 knockout mice from Ted and Valina Dawson, Johns Hopkins University, UCP2 knockout mice from Dong Kong and Bradford Lowell, Harvard University and cyclophilin D knockout mice from Stanley J. Korsmeyer, Harvard University. This work was supported by the Picower Foundation, the Hartman Foundation, the Falk Trust and NIH grants NS047085 (DJS), NS 054850 (DJS), K12GM088020 (JSP), HL35440 (PTS), RR025355 (PTS) and, DOD contract W81XWH-07-1-0170 (DJS).

Footnotes

Author contributions:

Dr. Surmeier was responsible for the overall direction of the experiments, analysis of data, construction of figures and communication of the results. Drs. Guzman and Sanchez were responsible for the design and execution of experiments, as well as the analysis of results. Dr. Wokosin provided expertise in optical approaches. Dr. Ilijic conducted the immunocytochemical experiments. Drs. Schumacker and Kondapalli were responsible for the generation of the TH-mito-roGFP mice; they also participated in the design, analysis and communication of the results.

Competing Financial Interests: None

References

- 1.Albin RL, Young AB, Penney JB. The functional anatomy of disorders of the basal ganglia. Trends in neurosciences. 1995;18:63–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schapira AH. Mitochondria in the aetiology and pathogenesis of Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:97–109. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70327-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puopolo M, Raviola E, Bean BP. Roles of subthreshold calcium current and sodium current in spontaneous firing of mouse midbrain dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:645–656. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4341-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan CS, et al. ‘Rejuvenation’ protects neurons in mouse models of Parkinson's disease. Nature. 2007;447:1081–1086. doi: 10.1038/nature05865. doi:nature05865 [pii]10.1038/nature05865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khaliq ZM, Bean BP. Pacemaking in dopaminergic ventral tegmental area neurons: depolarizing drive from background and voltage-dependent sodium conductances. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7401–7413. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0143-10.2010. doi:30/21/7401 [pii]10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0143-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guzman JN, Sanchez-Padilla J, Chan CS, Surmeier DJ. Robust pacemaking in substantia nigra dopaminergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2009;29:11011–11019. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2519-09.2009. doi:29/35/11011 [pii]10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2519-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dooley CT, et al. Imaging dynamic redox changes in mammalian cells with green fluorescent protein indicators. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:22284–22293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312847200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matlib MA, et al. Oxygen-bridged dinuclear ruthenium amine complex specifically inhibits Ca2+ uptake into mitochondria in vitro and in situ in single cardiac myocytes. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1998;273:10223–10231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicholls DG, Ferguson SJ. Bioenergetics. 3rd edn Vol. 3. Academic Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahle PJ, Waak J, Gasser T. DJ-1 and prevention of oxidative stress in Parkinson's disease and other age-related disorders. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.08.003. doi:S0891-5849(09)00473-0 [pii]10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehrenberg B, Montana V, Wei MD, Wuskell JP, Loew LM. Membrane potential can be determined in individual cells from the nernstian distribution of cationic dyes. Biophys J. 1988;53:785–794. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83158-8. doi:S0006-3495(88)83158-8 [pii]10.1016/S0006-3495(88)83158-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rasola A, Bernardi P. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore and its involvement in cell death and in disease pathogenesis. Apoptosis. 2007;12:815–833. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0723-y. doi:10.1007/s10495-007-0723-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krauss S, Zhang CY, Lowell BB. The mitochondrial uncoupling-protein homologues. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:248–261. doi: 10.1038/nrm1592. doi:nrm1592 [pii]10.1038/nrm1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brand MD, et al. Mitochondrial superoxide and aging: uncoupling-protein activity and superoxide production. Biochem Soc Symp. 2004:203–213. doi: 10.1042/bss0710203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrews ZB, et al. Uncoupling protein-2 is critical for nigral dopamine cell survival in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci. 2005;25:184–191. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4269-04.2005. doi:25/1/184 [pii]10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4269-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang CY, et al. Genipin inhibits UCP2-mediated proton leak and acutely reverses obesityand high glucose-induced beta cell dysfunction in isolated pancreatic islets. Cell Metab. 2006;3:417–427. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.010. doi:S1550-4131(06)00129-X [pii]10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Echtay KS, et al. Superoxide activates mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. Nature. 2002;415:96–99. doi: 10.1038/415096a. doi:10.1038/415096a415096a [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papa S, Skulachev VP. Reactive oxygen species, mitochondria, apoptosis and aging. Mol Cell Biochem. 1997;174:305–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Canet-Aviles RM, et al. The Parkinson's disease protein DJ-1 is neuroprotective due to cysteine-sulfinic acid-driven mitochondrial localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9103–9108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402959101. doi:10.1073/pnas.04029591010402959101 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonifati V, et al. Mutations in the DJ-1 gene associated with autosomal recessive early-onset parkinsonism. Science. 2003;299:256–259. doi: 10.1126/science.1077209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cookson MR. DJ-1, PINK1, and their effects on mitochondrial pathways. Mov Disord. 2010;25(Suppl 1):S44–48. doi: 10.1002/mds.22713. doi:10.1002/mds.22713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bender A, et al. High levels of mitochondrial DNA deletions in substantia nigra neurons in aging and Parkinson disease. Nat Genet. 2006;38:515–517. doi: 10.1038/ng1769. doi:ng1769 [pii]10.1038/ng1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bender A, et al. Dopaminergic midbrain neurons are the prime target for mitochondrial DNA deletions. J Neurol. 2008;255:1231–1235. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0892-9. doi:10.1007/s00415-008-0892-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krishnan KJ, Greaves LC, Reeve AK, Turnbull DM. Mitochondrial DNA mutations and aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1100:227–240. doi: 10.1196/annals.1395.024. doi:1100/1/227 [pii]10.1196/annals.1395.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nicholls DG. Oxidative stress and energy crises in neuronal dysfunction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1147:53–60. doi: 10.1196/annals.1427.002. doi:NYAS1147002 [pii]10.1196/annals.1427.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisenberg MJ, Brox A, Bestawros AN. Calcium channel blockers: an update. The American journal of medicine. 2004;116:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Becker C, Jick SS, Meier CR. Use of antihypertensives and the risk of Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2008;70:1438–1444. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000303818.38960.44. doi:01.wnl.0000303818.38960.44 [pii]10.1212/01.wnl.0000303818.38960.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ritz B, et al. L-type calcium channel blockers and Parkinson disease in Denmark. Ann Neurol. 2010;67:600–606. doi: 10.1002/ana.21937. doi:10.1002/ana.21937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.