Abstract

Noscapine is an opium-derived kinder-gentler microtubule-modulating drug, currently in Phase I/II clinical trials for cancer chemotherapy. Here, we report the synthesis of four more potent di-substituted brominated derivatives of noscapine, 9-Br-7-OH-NOS (2), 9-Br-7-OCONHEt-NOS (3), 9-Br-7-OCONHBn-NOS (4), and 9-Br-7-OAc-NOS (5) and their chemotherapeutic efficacy on PC-3 and MDA-MB-231 cells. The four derivatives were observed to have higher tubulin binding activity than noscapine and significantly affect tubulin polymerization. The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) for the interaction between tubulin and 2, 3, 4, 5 was found to be, 55 ± 6 µM, 44 ± 6 µM, 26 ± 3 µM, and 21 ± 1 µM respectively, which is comparable to parent analog. The effects of these di-substituted noscapine analogs on cell cycle parameters indicate that the cells enter a quiescent phase without undergoing further cell division. The varying biological activity of these analogs and bulk of substituent at position-7 of the benzofuranone ring system of the parent molecule was rationalized utilizing predictive in silico molecular modeling. Furthermore, the immunoblot analysis of protein lysates from cells treated with 4 and 5, revealed the induction of apoptosis and down-regulation of survivin levels. This result was further supported by the enhanced activity of caspase-3/7 enzymes in treated samples compared to the controls. Hence, these compounds showed a great potential for studying microtubule-mediated processes and as chemotherapeutic agents for the management of human cancers.

Keywords: Noscapine, anticancer activity, tubulin polymerization

GRAPHICAL ABSTRACT

Microtubules, formed by α and β-tubulin heterodimers, are essential constituents of the cytoskeleton in eukaryotic cells and are involved in a number of important structural and regulatory functions, including the maintenance of cell shape and intracellular transport machinery as well as cell growth and mitosis [1–3]. Over the past few decades, microtubule-active drugs have met with abundant success in the oncology clinic for a wide-spectrum of malignancies [4, 5]. Nonetheless, several impediments associated with their clinical use, such as non-specific toxicity, drug resistance, and water insolubility, have resulted in a sub-optimal realization of their clinical potential [6, 7]. Microtubules, which are involved in a complex process of cell division, are now a well-established target for the chemotherapy of many types of cancers [8, 9]. Two major classes of tubulin-interacting drugs either over-polymerize or de-polymerize the involved subunits leading to devastation of cytoskeleton in later stages of cell division. For example, drugs such as Taxol perturb the normal microtubule assembly dynamics by ‘hyperpolymerizing’ the microtubules [4] whereas compounds like maytansinoids inhibit microtubule assembly and interfere with the polymerization dynamics [10]. In addition to above, a variety of synthetic small molecules have also been used as inhibitors of polymerization, which compete with colchicine binding site of tubulin. Few Colchicine like compounds are in clinical trials e.g. Combretastatin A-4P (CA4P) [11], ZD6216 [12], N-(3-hydroxy-4-methoxyphenyl)-3,4,5-trimethoxy benzenesulfonamide [13], and 1-methyl -1H- indole -5-sulfonic acid (3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)amide [14]. A list of various microtubule polymerizing and de-polymerizing agents that are currently in use and in clinical development are presented in Table 1. Another important microtubule polymerization inhibitor, Noscapine, was studied extensively for its tubulin binding anticancer properties in the last decade [15, 16]. It has been known for some time that noscapine can act as a potent anticancer agent in certain in vivo models [17]. Although it appears to be a weak inhibitor of microtubule polymerization, its low cost, ready availability and a favorable toxicity profile allow further exploration of this natural product.

Table 1.

Microtubule targeting cancer therapeutics

| S/N | Tubulin Antagonistic Activity |

Drug/ Drug Candidate | Clinical Development Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Polymerization Antagonists |

Vinblastine | In clinical use |

| 2 | Vincristine | In clinical use | |

| 3 | Vinorelbine | In clinical use | |

| 4 | Vinflunine | Phase III | |

| 5 | Cryptophycin 52 | Phase III done | |

| 6 | Halichondrins | Phase I | |

| 7 | Dolastatins | Phase I & II done | |

| 8 | Hemiasterlins | Phase I | |

| 9 | Colchicine | Failed Trials (Toxicity) | |

| 10 | Combretastatins | Phase I | |

| 11 | 2-methoxy-estradiol | Phase I | |

| 12 | E7010 | Phase I & II | |

| 13 | De-polymerization Antagonists |

Paclitaxel (taxol) | In clinical use |

| 14 | Docetaxel (taxotere) | Phase I, II and III | |

| 15 | Epothilon | Phase I, II and III | |

| 16 | Discodermolide | Phase I | |

| 17 | Griseofulvin | Phase I | |

Currently, noscapine is in phase I/II of clinical trials for the treatment of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and the clinical trials employing it for the treatment of multiple myeloma have recently been completed (www.clinicaltrials.gov). In our previous report we discovered noscapine as a structural variant of colchicine like toxin [18]. Our group has been involved in the synthesis and anticancer property evaluation of many of the noscapinoids. These include the derivatization of the isoquinoline ring system of the molecule to prepare chloro, bromo, fluoro and iodo analogs. Also, more noscapinoids were prepared using nitration reaction on aromatic ring of the isoquinoline ring system and also by complete reduction of lactone moiety in the benzofuranone ring system followed by halogenation reactions. Ever since, several groups including ours, have been actively engaged in the synthesis of in silico guided, more potent noscapine analogs with potentially better pharmacological profiles [8, 19, 20]. Recently, we reported the synthesis of second-generation 7-position benzofuranone noscapine analogs that offered better anti-proliferative activity than the founding molecule [21]. Anderson et al synthesized novel noscapine analogs, which have shown potential as S-phase arresting anti-mitotic agents [22]. Their approach involved exploitation of the methyl ether cleavage reaction on the benzofuranone ring system using Grignard reagent.

Here, we describe the chemical synthesis of a third generation di-substituted bromo analogs of noscapine, which were evaluated for their tubulin polymerization and antiproliferative properties. In silico molecular modeling data were employed to rationalize and comprehend their observed biological activity patterns. They were examined for their anti-proliferative activity against prostate and breast cancer cells. This has contributed to an enhanced understanding of structure-based drug design to facilitate drug discovery and development of a novel class of tubulin-active, non-toxic agents.

In silico docking and molecular simulation studies

Molecular simulations and in silico docking studies were performed to gain insights into how the compounds 2, 3, 4 and 5 docked into the active site independently at the interface of the alpha and beta domains of the tubulin dimer (Figure 1A–D). The binding orientations were held similar for all of the ligand-tubulin complexes. The docking results suggest that noscapine structure can be divided into two distinct halves a) the tetrahydroisoquinoline moiety which can insert deep and interact closely with the tubulin dimer and b) dimethoxyisobenzofuranone group gets closer to GTP in ligand-tubulin docked complex. These initial docked complexes were used as the starting conformations for further studies using molecular dynamics simulations and free energy calculations. Each complex was simulated for at least 30 ns in explicit water. Our in silico modelling results suggested that compound 2 has the strongest affinity for the tubulin dimer. In general, the bromo-substituted compounds adopted a similar binding configuration in the active site which is different from the substituted compounds.

Figure 1. Molecular docking analysis of di-substituted noscapine analogs.

Conformations of compounds in tubulin active site, hydrogen bond interactions (left) and compound orientation in binding pocket (right) for compounds 2, 3, 4 and 5 (A, B, C, and D) respectively. Compounds are shown in ball and stick model with green color.

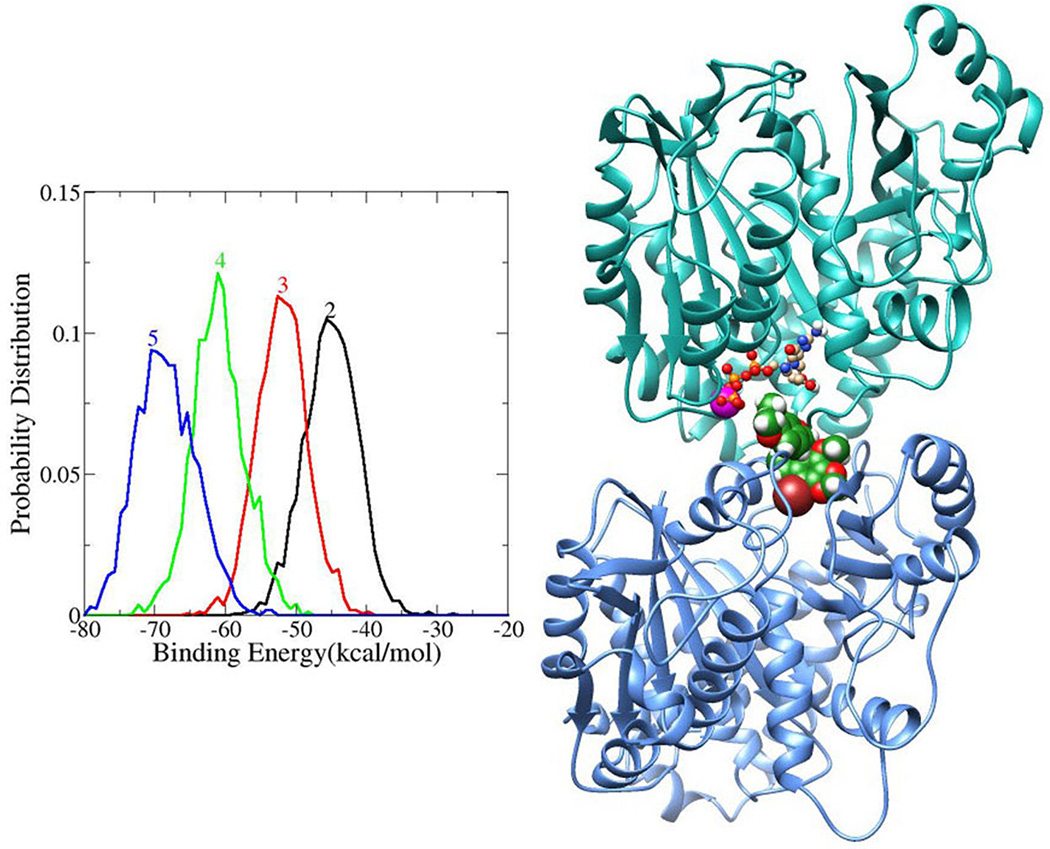

The free energy of binding the compound into the active site was calculated for each resulting snapshot from the molecular dynamics simulations. Distributions of the binding free energies for all of the four compounds are shown in Figure 2. For each complex, 2000 conformations were generated using MD simulations and the distribution of binding energies of these complexes is shown in Figure 2. The relative binding energies of the ligands follow the order of the experimentally equilibrium dissociation constant (KD), except for compound 3. The hydrogen bonds between the ligands and tubulin were calculated using the PTRAJ module in AMBER 10 program,[38] based on a cut off distance of 3.6 Å and an angle of 120°. The enhanced stability of the complexes can be attributed to a hydrogen bond donor on the compound. Well-formed hydrogen bonds are shown in Figure 1 and the hydrogen bond distances and occupancies are given in Table I. The –OH hydrogen bond donor in ligand-2 forms weak hydrogen bonds with GTP, with a low occupancy and a distance of 3.3 Å. But other substitution groups (compounds 3, 4, and 5) forms hydrogen bonds with high occupancy and stabilizes the complexes.

Figure 2. Binding free energy calculation of ligand-tubulin complex and docked pose of compound 2 showing interaction with tubulin.

Binding free energies (kcal/mol) of the compounds (2, 3, 4 and 5) calculated from the MD trajectory using MMGBSA method (left) and model representation of compound 2 in tubulin heterodimer (α- subunit in cyan and β-subunit in light blue) (right). Compound 2 was shown in space filling model (green), GTP in ball and stick model, Mg2+ (pink) in VDW model and Br-in brown color.

Chemical synthesis of disubstituted noscapinoids

The synthetic strategy started from the synthesis of bromonoscapine as reported by us earlier [8]. To prepare a series of disubstituted noscapinoids, initially we used the procedure adopted by Anderson et al [22] on parent molecule, noscapine to perform demethylation reaction on bromonoscapine. Although we were successful in obtaining the desired compound, the yield was not satisfactory and the work-up procedure was cumbersome, possibly due to interference of halogen atom present in bromonoscapine. Our synthetic efforts towards optimization of yield and reaction process lead to the discovery of a new reagent combination for methyl ether cleavage on position-7 of the benzofuranone ring system of noscapine. Use of two equivalents of sodium azide in combination with half equivalents of sodium iodide in anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF) resulted in clean methyl ether cleavage of bromonoscapine to produce the key intermediate 2.

In this method, the work-up required the removal of solvents to obtain crude residue followed by extraction in ethyl acetate and washing with water and brine to remove salts. Thus, this offered a simple, economical and an easy work-up procedure compared to the one reported previously [8]. Compound 2 served as key intermediate in our synthesis and further derivatized using acylation and isocyanate chemistry to prepare compounds 3-5. Acylation reaction on this key intermediate was performed to prepare compound 3 and acetic anhydride was used as acetylating agent in presence of DMAP in the synthesis (Scheme 1). Further derivatization of the phenolic group was performed using isocyanate chemistry to produce corresponding carbamates [21]. The two carbamate derivatives, compounds 4 and 5, were prepared by the reaction of ethyl and benzyl isocyanates respectively with key intermediate 2 in presence of DMAP in moderate yields.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of di-substituted noscapine analogs

Reagents & Conditions a) NaN3Nal, DMF, 140 °C, 3h. b) Ac2O, Dimethylamino pyridine, THF, rt, 4h. c) Dimethylamino pyridine, CH2Cl2, RNCO, rt, 6–8 h.

All the di-substituted noscapinoids were evaluated for their tubulin de-polymerization ability and anti-cell proliferative ability against two cancer cell lines.

Binding of the di-substituted noscapinoids to tubulin

The binding of the noscapinoids, 2, 3, 4 or 5 to tubulin was studied by measuring the quenching of the intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of tubulin in the presence of the compounds. The noscapinoids reduced the fluorescence emission intensity in a concentration-dependent manner indicating the binding of the noscapinoids to tubulin. The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) for the interaction between tubulin and compounds 2, 3, 4 and 5 was found to be, 55 ± 6 µM, 44 ± 6 µM, 26 ± 3 µM, and 21 ± 1 µM respectively as obtained from three independent experiments. Our results suggest that compound 5 forms more stable complex with tubulin with lowest (KD) value.

Effect of di-substituted noscapinoids on tubulin polymerization

The rate and extent of tubulin polymerization was monitored using a light scattering assay at 350 nm. The effect of the di-substituted noscapinoids compounds 2, 3, 4 and 5 on tubulin polymerization was studied by measuring the absorbance at 350 nm. The decrease in the scattering at 350 nm was concentration dependent. Compound 2 has shown significant decrease in scattering at 25 µM showing significant inhibition in tubulin polymerization.

Novel di-substituted noscapinoids show significant antiproliferative activity

In our earlier studies, we observed that bromo noscapine was highly effective against prostate and breast cancer cells. As the current di-substituted bromo analogs are derivatives of bromo noscapine, we chose to test their efficacy against prostate and breast cancer cell lines. The value (drug concentration at which 50% inhibition of cell proliferation occurs) of these synthesized compounds are presented in Table 3. Cells were treated for 48 h with increasing gradient concentrations of the analogs and the percentage of cell proliferation was measured using MTT assay.

Table 3.

In vitro cytotoxicity (IC50, µM) of disubstituted Noscapine analogs.

| IC50 (µM) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | R | PC-3 | MDA-MB-231 |

| 2 | OH | 5.6±0.08 | 2.2±0.00 |

| 3 | OAc | 48.9±0.89 | 2.5±0.09 |

| 4 | OCONHEt | 22.0±2.45 | 3.9±0.73 |

| 5 | OCONHBn | 49.4±0.94 | 20±2.92 |

Our result shows with the increase in the bulk of substituent on position-7, an increase in the IC50s was observed (Table 3). But the efficacy of compounds 4 and 5 however increased irrespective of the cell line, indicating the role of bulk of the substituent in determining the biological activity. MDA-MB 231 cells showed comparatively high % cell survival with compound 5, IC50 value of 20±2.92 µM (Table 3). Similar pattern was observed with this compound in PC-3 cells with IC50 values of 49.4±0.94 µM (Table 3). The differences in the IC50 values of these analogs can be attributed to the bulk of functional group on position-7 of the benzofuranone ring system of the parent molecule, noscapine.

Novel di-substituted noscapinoids induce apoptosis

We also examined the effect of these di-substituted noscapine analogs on cell cycle parameters and percent sub-G1 cells (apoptotic index) as a function of time in MDA-MB-231 cells using fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis. We studied effect of compounds 2, 3 at 10 µM, 4 and 5 at 25 µM, dosage for 0–48 h of treatment. Here, we have shown the cell cycle profile in a 3 dimensional disposition for compounds 2–5 at different time points (0–48 h) (Figure 6). The bar graphs represent the percent G2/M and sub-G1 populations at different time points for compounds 2–5. Cell cycle progression and cell death can be monitored effectively using fluorescently labeled DNA. The cells with 2N DNA represent the G1 phase while cells with tetraploid (4N) DNA represent G2 and M phases. All the other cells which are in the process of duplication, come in between the 2N and 4N DNA and represent the cells in S Phase. The distribution of cell population between G2/M and sub-G1 has been represented as bar graphs in the panels for each compound. We observed that the cells were arrested in G2-M phase followed by the emergence of sub-G1 population.

Figure 6. Cell cycle profile in a 3 dimensional disposition for compounds 2–5 at different time points (0–48h).

The bar-graphs represent the percent G2/M and sub-G1populations at different time points for compounds 2–5. The distribution of cell population between G2/M and sub-G1 has been represented as bar graphs in the panels for each compound.

Di-substituted noscapinoids induce apoptosis via survivin down-regulation and caspase-3 activation

A decrease in expression levels of survivin, an anti-apoptotic protein, by noscapine analogs has been shown to cause death in cancer cells by apoptosis. To evaluate a similar effect of di-substituted noscapinoids, protein lysates from treated and control cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis. Compounds 4 and 5 caused a decline in the survivin expression while increasing the cleaved PARP levels. In contrast, compounds 2 and 3 showed no change in survivin levels while still caused enhanced cleaved PARP expression when compared to control.

To further corroborate the observation that di-substituted noscapinoids induce apoptosis, the protein lysates from treated and control cells were analyzed for caspase-3/7 activity compound. The caspase-3/7 activity upon treating with compounds 2, 3, 4, and 5 was measured by detecting the luminescence generated upon cleavage of Z-DEVD-aminoluciferin. The caspase activity of treated samples was higher than that observed in case of control in congruence with the increased cleaved PARP levels as observed by immunoblot analysis. Hence, all the four compounds induced apoptosis in cells. Compound 5 showed the highest caspase-3/7 activity indicating that it effectively induced apoptosis in cancer cells compared to the others three compounds.

Noscapinoids represent a new generation of anticancer agents that modulate microtubule dynamics but do not significantly alter the total polymer mass of tubulin. Earlier reports have shown that EM011 (bromonoscapine), a brominated noscapine analog, has potent antiproliferative and proapoptotic activity in hormone-refractory breast cancer and drug-resistant lymphoma models [39, 40]. As a next step to further improvise the efficacy of noscapinoids, in our current study, in silico molecular modeling was employed to predict the rational design of novel third-generation di-substituted noscapine analogs. The compounds 2, 3, 4 and 5 docked into the active site independently at the interface of the alpha and beta domains of the tubulin dimer (Figure 1A–D). The binding free energy of compounds into the active site was calculated for each resulting snapshot from the molecular dynamics simulations. The –OH hydrogen bond donor in compound 2 forms weak hydrogen bonds with GTP, with a low occupancy and a distance of 3.3 Å. But compounds 3, 4, and 5 form hydrogen bonds with high occupancy and stabilize the complexes (Table 2).

Table 2.

Hydrogen bond distance (Å) and % occupancy

| Molecule | Residue Number |

Distance (Å) | % Occupancy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donor | Acceptor | |||

| 2 | LIG@O6@H | GTP@O1A | 3.3 | 1.8 |

| ASN100 @ND2@H | LIG@O5 | 3.0 | 25.5 | |

| 3 | ASN 100@ND2@H | LIG@O5 | 3.0 | 95.6 |

| 4 | LIG@N2@H | GTP@O3G | 3.0 | 75.0 |

| LIG@N2@H | GTP@O1G | 3.3 | 66.1 | |

| ASN 100@ND2@H | LIG@O5 | 3.1 | 86.2 | |

| 5 | LIG@N2@H | GTP@O3G | 3.0 | 77.5 |

| LIG@N2@H | GTP@O1G | 3.4 | 37.4 | |

| ASN 100@ND2@H | LIG@O5 | 3.1 | 92.7 | |

| ASN 691@ND2@H | LIG@O5 | 3.3 | 10.0 | |

Note: LIG – corresponding molecule

Binding of all four compounds analyzed by measuring the quenching of fluorescence emission revealed reduced fluorescence emission intensity in a concentration-dependent manner indicated the binding of the noscapinoids to tubulin. The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) for the interaction between tubulin and compound 2, 3, 4 and 5 was calculated and found to be, 55 ± 6 µM, 44 ± 6 µM, 26 ± 3 µM, and 21 ± 1 µM respectively (Figure 3). Compound 5 formed the most stable complex with tubulin. The rate and extent of tubulin polymerization were monitored using a light scattering assay at 350 nm. The anti-tubulin activity of these di-substituted noscapine analogs indicated that all four analogs inhibited the light scattering signal in a concentration-dependent manner, suggesting that these di-substituted analogs can bind to tubulin and inhibit microtubule assembly. Out of all, compound 2 showed the maximum inhibition of light scattering signal, thus giving a glimpse of considerable potency to inhibit the formation of microtubule assembly.

Figure 3. Fluorescence quenching of tubulin by derivatives of noscapine.

Double reciprocal plots showing a dissociation constant (KD) of 55 ± 6 µM for compound 2 binding to tubulin, 44 ± 6 µM for compound 3, 26 ± 3 µM for compound 4 and 21 ± 1 µM for compound 5. Values are mean ± S.D. for three independent experiments performed in triplicate (p < 0.05).

Further, all four compounds have shown higher cytotoxicity with lower IC50 against MDA-MB-231 as compared to PC-3 (Figure 5). Compound 2 had significant cytotoxicity against both the cell lines. The precise mechanism of action of these compounds was further examined via cell cycle studies in MDA-MB-231 cells. Flow-cytometric analysis using the DNA intercalating dye, propidium iodide (PI), was employed to monitor cell cycle progression on the basis of DNA quantitation. From FACS analysis, it was observed that majority of treated cells progressed to an apparent sub-G1 status (Figure 6). Sustained G2/M arrest was observed (15–20%) upon treatment followed by emergence of sub-G1 population. Continued accumulation of sub-G1 population upon treatment with all the four compounds suggested the induction of cell death. However, compound 2 resulted in an early induction of cell death with a marginal increase (from 10% to 35%) but a sustained G2/M arrest even at 48h. The other 3 compounds led to a sudden induction of cell death at 48 h (80–90%) preceded by a sustained mitotic arrest.

Figure 5. Percentage of cell survival measured using MTT assay.

A and B represent the sensitivity profile of PC-3 and MDA-MB 231 cells to the four di-substituted noscapine analogs. C is a bar-graphical representation of IC50 values of noscapine analogs in PC-3 and MDA-MB 231 cells. The values and error bars shown in all the graphs represent average and standard deviations, respectively, of three independent experiments (p <0.05).

The levels of cleaved poly (ADP) ribose polymerase 1 (PARP 1), and survivin as evaluated by immunoblot analysis of the MDA-MB-231 cell lysates following treatment with compounds 2, 3, 4 and 5 (Figure 7) suggested that although each synthesized analog showed cytotoxicity within a narrow range for the cell lines used in the study, differential sensitivity of a particular analog towards cell lines from varying tissue origin existed. These differences are complex to comprehend, and can perhaps be attributable to the presence of varying tubulin isotype expression and mutations in the tubulin gene in different cell types [41–43]. It is also likely that altered expression of survivin and drug resistance mechanisms in cell lines from different tissue types dictate cellular sensitivities [44]. Survivin, an antiapoptotic member of the inhibitor of apoptosis (IAP) family is known to block apoptosis by inhibiting caspases and antagonizing mitochondria-dependent apoptosis [45]. Survivin is over-expressed in many types of cancers (of different tissue origins), but not in their respective normal tissues [46]. Thus it was necessary to check the effect of these compounds on the expression of survivin levels as part of its anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic action. According to our observations, compounds 4 and 5 caused a decline in the survivin expression. In contrast, compounds 2 and 3 showed no change in survivin levels. Upon cleavage by upstream proteases in an intracellular cascade, the activation of caspase-3 and its subsequent cleavage of PARP are considered as hallmarks of the apoptotic process. An enhanced cleaved PARP expression among the cell lysates following treatment with compounds 2, 3, 4 and 5 was observed upon probing with a cleaved PARP specific antibody (Figure 7). Further the protein lysates from treated and control cells were analyzed for caspase-3/7 activity. All the four treated protein lysates have shown enhanced caspase 3/7 activities as compared to control. Out of four compounds, compound 5 showed the highest caspase-3/7 activity indicating that it effectively induced apoptosis in cancer cells compared to the others. Overall, these results show activation of caspase-3 and PARP cleavage suggesting that these compounds induced apoptotic cell death in MDA-MB-231 cells. Of all the 4 compounds tested, compound 5 resulted in greater decline of survivin expression, followed by increase in caspase 3/7 activity, while compound 2 was found to have the lowest IC50 value against both the cell lines tested. These results indicate that the compounds tested might exert their efficacy via differential mechanism of action thus warranting further mechanistic investigations.

Figure 7. Immunoblot analysis of surviving and cleaved PARP protein and caspase-3/7 activity with compounds 2, 3, 4, and 5.

A. Protein samples from treated and control cells probed for survivin and cleaved PARP. β-actin was the loading control. B. Bar graphical representation of relative fluorescence of caspase-3/7 activity in control and treated samples.

Successful chemotherapy relies on the strategic induction of robust apoptosis in cancer cells while sparing normal cells. Essentially, chemotherapeutic agents induce cell death by arresting cell cycle progression, up regulating the expression of pro-apoptotic molecules while down regulating survival signaling players that encumber apoptosis. Our results have contributed to an enhanced understanding of structure-based drug design targeting tubulin, in order to develop novel noscapine analogs with enhanced anticancer efficacy thus affecting microtubule-mediated processes and further inducing the apoptotic pathway.

Supplementary Material

Figure 4. Tubulin polymerization determined via turbidity (at 350 nm).

Relative absorbance of compounds 2–5 is measured with increasing concentrations (0–25µM) indicated compounds for 30 min with 12 µM tubulin.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported in part by grant to RA from the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (1R00CA131489). Work in DH laboratory is supported in part by the grants from NSF CAREER MCB-0953061 and the Georgia Cancer Coalition. R. M., SR. G., P. K., M.L., KK. G., M. N. conducted the research and analyzed the data, R. M., SR.G., V. T. and R. A. designed the research and wrote the manuscript, R.M., SR. G., D. H., V.T., D.P., MD. R. and R.A. contributed to the editing of the manuscript, and provided reagents, materials and analysis tools. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- ATCC

American type cell culture

- MTT

tetrazolium bromide solution

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- IC50

inhibitory concentration 50%

- Nos

Noscapine

- EM011

bromonoscapine

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

- KD

dissociation constant

- FACS

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- PARP

Poly ADP ribose polymerase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.McIntosh JR, Grishchuk EL, West RR. Chromosome-microtubule interactions during mitosis. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2002;18:193–219. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.032002.132412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gundersen GG, Cook TA. Microtubules and signal transduction. Current opinion in cell biology. 1999;11:81–94. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)80010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nogales E. Structural insights into microtubule function. Annual review of biochemistry. 2000;69:277–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dumontet C, Jordan MA. Microtubule-binding agents: a dynamic field of cancer therapeutics. Nature reviews. Drug discovery. 2010;9:790–803. doi: 10.1038/nrd3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perez EA. Microtubule inhibitors: Differentiating tubulin-inhibiting agents based on mechanisms of action, clinical activity, and resistance. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2009;8:2086–2095. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Checchi PM, Nettles JH, Zhou J, Snyder JP, Joshi HC. Microtubule-interacting drugs for cancer treatment. Trends in pharmacological sciences. 2003;24:361–365. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(03)00161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen SM, Meng LH, Ding J. New microtubule-inhibiting anticancer agents. Expert opinion on investigational drugs. 2010;19:329–343. doi: 10.1517/13543780903571631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aneja R, Vangapandu SN, Lopus M, Viswesarappa VG, Dhiman N, Verma A, Chandra R, Panda D, Joshi HC. Synthesis of microtubule-interfering halogenated noscapine analogs that perturb mitosis in cancer cells followed by cell death. Biochemical pharmacology. 2006;72:415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.YM Lopus M, Wilson L. Microtubule Dynamics. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopus M. Antibody-DM1 conjugates as cancer therapeutics. Cancer letters. 2011;307:113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.West CM, Price P. Combretastatin A4 phosphate. Anti-cancer drugs. 2004;15:179–187. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200403000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis PD, Dougherty GJ, Blakey DC, Galbraith SM, Tozer GM, Holder AL, Naylor MA, Nolan J, Stratford MR, Chaplin DJ, Hill SA. ZD6126: a novel vascular-targeting agent that causes selective destruction of tumor vasculature. Cancer research. 2002;62:7247–7253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.JC M. Benzenesulfonamides and benzamides as therapeutic agents, USA. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prinz H. Recent advances in the field of tubulin polymerization inhibitors. Expert review of anticancer therapy. 2002;2:695–708. doi: 10.1586/14737140.2.6.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ye K, Ke Y, Keshava N, Shanks J, Kapp JA, Tekmal RR, Petros J, Joshi HC. Opium alkaloid noscapine is an antitumor agent that arrests metaphase and induces apoptosis in dividing cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95:1601–1606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ke Y, Ye K, Grossniklaus HE, Archer DR, Joshi HC, Kapp JA. Noscapine inhibits tumor growth with little toxicity to normal tissues or inhibition of immune responses. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII. 2000;49:217–225. doi: 10.1007/s002620000109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warolin C. [Pierre-Jean Robiquet] . Revue d'histoire de la pharmacie. 1999;47:97–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aneja R, Dhiman N, Idnani J, Awasthi A, Arora SK, Chandra R, Joshi HC. Preclinical pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of noscapine, a tubulin-binding anticancer agent. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2007;60:831–839. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0430-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou J, Gupta K, Aggarwal S, Aneja R, Chandra R, Panda D, Joshi HC. Brominated derivatives of noscapine are potent microtubule-interfering agents that perturb mitosis and inhibit cell proliferation. Molecular pharmacology. 2003;63:799–807. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.4.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aneja R, Vangapandu SN, Lopus M, Chandra R, Panda D, Joshi HC. Development of a novel nitro-derivative of noscapine for the potential treatment of drug-resistant ovarian cancer and T-cell lymphoma. Molecular pharmacology. 2006;69:1801–1809. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.021899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mishra RC, Karna P, Gundala SR, Pannu V, Stanton RA, Gupta KK, Robinson MH, Lopus M, Wilson L, Henary M, Aneja R. Second generation benzofuranone ring substituted noscapine analogs: synthesis and biological evaluation. Biochemical pharmacology. 2011;82:110–121. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson JT, Ting AE, Boozer S, Brunden KR, Crumrine C, Danzig J, Dent T, Faga L, Harrington JJ, Hodnick WF, Murphy SM, Pawlowski G, Perry R, Raber A, Rundlett SE, Stricker-Krongrad A, Wang J, Bennani YL. Identification of novel and improved antimitotic agents derived from noscapine. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2005;48:7096–7098. doi: 10.1021/jm050674q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verma AK, Bansal S, Singh J, Tiwari RK, Kasi Sankar V, Tandon V, Chandra R. Synthesis and in vitro cytotoxicity of haloderivatives of noscapine. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry. 2006;14:6733–6736. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ravelli RB, Gigant B, Curmi PA, Jourdain I, Lachkar S, Sobel A, Knossow M. Insight into tubulin regulation from a complex with colchicine and a stathmin-like domain. Nature. 2004;428:198–202. doi: 10.1038/nature02393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.KT Dennington R, Millam J, Eppinnett K, Hovell WL, Gilliland R. GaussView. Shawnee Mission, KS: Semichem, Inc.; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. Journal of computational chemistry. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Case DA, Cheatham TE, 3rd, Darden T, Gohlke H, Luo R, Merz KM, Jr, Onufriev A, Simmerling C, Wang B, Woods RJ. The Amber biomolecular simulation programs. Journal of computational chemistry. 2005;26:1668–1688. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.CP Cornell WD, Bayly CI, Gould IR, Merz KM, Ferguson DM, Spellmeyer DC, Fox T, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA. A Second Generation Force Field for the Simulation of Proteins, Nucleic Acids, and Organic Molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:5179–5197. [Google Scholar]

- 30.HD Urmi D. Reoptimization of the AMBER Force Field Parameters for Peptide Bond (Omega) Torsions Using Accelerated Molecular Dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:16590–16595. doi: 10.1021/jp907388m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, Wolf RM, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA, Case DA. Development and testing of a general amber force field. Journal of computational chemistry. 2004;25:1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.CJ Jorgensen WL, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulation liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 33.CG Ryckaert JP, Berendsen HJC. Numerical integration of the Cartesian Equations of Motion of a System with Constraints: Molecular Dynamics of n-Alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 34.YD Darden T, Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: An W log (N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kollman PA, Massova I, Reyes C, Kuhn B, Huo S, Chong L, Lee M, Lee T, Duan Y, Wang W, Donini O, Cieplak P, Srinivasan J, Case DA, Cheatham TE., 3rd Calculating structures and free energies of complex molecules: combining molecular mechanics and continuum models. Accounts of chemical research. 2000;33:889–897. doi: 10.1021/ar000033j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lopus M, Oroudjev E, Wilson L, Wilhelm S, Widdison W, Chari R, Jordan MA. Maytansine and cellular metabolites of antibody-maytansinoid conjugates strongly suppress microtubule dynamics by binding to microtubules. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2010;9:2689–2699. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aneja R, Miyagi T, Karna P, Ezell T, Shukla D, Vij Gupta M, Yates C, Chinni SR, Zhau H, Chung LW, Joshi HC. A novel microtubule-modulating agent induces mitochondrially driven caspase-dependent apoptosis via mitotic checkpoint activation in human prostate cancer cells. European journal of cancer. 2010;46:1668–1678. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Case DA, Darden TA, I Cheatham TE, Simmerling CL, Wang J, Duke RE, Luo R, Crowley M, Walker RC, Zhang W, Merz KM, Wang B, Hayik S, Roitberg A, Seabra G, Kolossváry, Wong KF, Paesani F, Vanicek J, Wu X, Brozell SR, Steinbrecher T, Gohlke H, Yang L, Tan C, Mongan J, Hornak V, Cui G, Mathews DH, Seetin MG, Sagui C, Babin V, Kollman PA. AMBER 10. San Francisco: University of California; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aneja R, Liu M, Yates C, Gao J, Dong X, Zhou B, Vangapandu SN, Zhou J, Joshi HC. Multidrug resistance-associated protein-overexpressing teniposide-resistant human lymphomas undergo apoptosis by a tubulin-binding agent. Cancer research. 2008;68:1495–1503. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aneja R, Zhou J, Zhou B, Chandra R, Joshi HC. Treatment of hormone-refractory breast cancer: apoptosis and regression of human tumors implanted in mice. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2006;5:2366–2377. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cowan NJ, Dudley L. Tubulin isotypes and the multigene tubulin families. International review of cytology. 1983;85:147–173. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62372-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kavallaris M, Kuo DY, Burkhart CA, Regl DL, Norris MD, Haber M, Horwitz SB. Taxol-resistant epithelial ovarian tumors are associated with altered expression of specific betatubulin isotypes. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1997;100:1282–1293. doi: 10.1172/JCI119642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huzil JT, Chen K, Kurgan L, Tuszynski JA. The roles of beta-tubulin mutations and isotype expression in acquired drug resistance. Cancer informatics. 2007;3:159–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kavallaris M, Tait AS, Walsh BJ, He L, Horwitz SB, Norris MD, Haber M. Multiple microtubule alterations are associated with Vinca alkaloid resistance in human leukemia cells. Cancer research. 2001;61:5803–5809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mita AC, Mita MM, Nawrocki ST, Giles FJ. Survivin: key regulator of mitosis and apoptosis and novel target for cancer therapeutics. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2008;14:5000–5005. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ambrosini G, Adida C, Altieri DC. A novel anti-apoptosis gene, survivin, expressed in cancer and lymphoma. Nature medicine. 1997;3:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.