Abstract

The Government of Ghana has taken important steps to mitigate the impact of unsafe abortion. However, the expected decline in maternal deaths is yet to be realized. This literature review aims to present findings from empirical research directly related to abortion provision in Ghana and identify gaps for future research. A total of four (4) databases were searched with the keywords “Ghana and abortion” and hand review of reference lists was conducted. All abstracts were reviewed. The final include sample was 39 articles. Abortion-related complications represent a large component of admissions to gynecological wards in hospitals in Ghana as well as a large contributor to maternal mortality. Almost half of the included studies were hospital-based, mainly chart reviews. This review has identified gaps in the literature including: interviewing women who have sought unsafe abortions and with healthcare providers who may act as gatekeepers to women wishing to access safe abortion services.

Keywords: Abortion, Ghana, Review

Introduction

Maternal mortality is a large and un-abating problem, mainly occurring in the developing world. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), UNFPA and the World Bank, 287,000 women die each year world-wide from pregnancy-related causes1. Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest maternal mortality ratio in the world of 500 per 100,000 births. WHO estimates 47,000 of these deaths per year are attributable to unsafe abortion, making abortion a leading cause of maternal mortality2. Not all unsafe abortions result in death, disability or complications. The morbidity and mortality associated with unsafe abortion depend on the method used, the skill of the provider, the cleanliness of the instruments and environment, the stage of the woman’s pregnancy and the woman’s overall health3. It is estimated that 5 million women per year from the developing world are hospitalized for complications resulting from unsafe abortions, resulting in long and short-term health problems4. The health consequences and burdens resulting from unsafe abortion disproportionately affect women in Africa5.

Unsafe abortion is defined by WHO as a procedure for terminating an unintended pregnancy carried out either by persons lacking the necessary skills or in an environment that does not conform to minimum medical standards, or both6. Approximately 21.2 million unsafe abortions occur each year in developing regions of the world1,7. Over 99% of all abortion-related deaths occur in developing countries. In sub-Saharan Africa, one in 150 women will die from complications of this procedure6.

Although only 24% of abortions worldwide are performed in sub-Saharan Africa, almost half of deaths related to this procedure occur in the region4, 8. In many countries in sub-Saharan Africa women’s access to safe abortion and post-abortion care for complications is hampered by restrictive laws, socio-cultural barriers, and inadequate resources to provide safe abortion4, 9–12.

The UN Millennium Development Goal (MDG) number 5 aims to reduce by three quarters the number of maternal deaths in the developing world. Without tackling the problems of unsafe abortion MDG 5 will not be reached13, 14.

Ghana

Ghana, a country in West Africa, has a population of approximately 24 million people. The average per capita income is approximately $181015, placing Ghana in the middle income bracket. Ghana has a similar pattern of health as other countries in the region, characterized by a persistent burden of infectious disease among poor and rural populations, and growing non-communicable illness among the urban middle class. Following generalized progress in child vaccination rates through the 1980s and 1990s, and corresponding declines in infant and child mortality (from 120/1000 in 1965 to 66/1000 in 1990), progress has stalled maternal and under 5 indicators in rural areas in the past decade. The national under-five mortality rate remains at 78 deaths/1,000 live births16. Maternal death is currently estimated at 350 per 100,000 live births17.

In Ghana, abortion complications are a large contributor to maternal morbidity and mortality. According to the Ghana Medical Association, abortion is the leading cause of maternal mortality, accounting for 15–30% of maternal deaths18, 19. Further, for every woman who dies from an unsafe abortion, it is estimated that 15 suffer short and long-term morbidities20.

Compared to other countries in the region, the laws governing abortion in Ghana are relatively liberal. Safe abortion, performed by a qualified healthcare provider, has been part of the Reproductive Health Strategy since 200319, 21. When performed by well-trained providers in a clean environment, abortion is one of the safest medical procedures with complications estimated at 1 in 100,0008.

Currently in Ghana, abortion is a criminal offense regulated by Act 29, section 58 of the Criminal code of 1960, amended by PNDCL 102 of 198522. However, section 2 of this law states abortion may be performed by a registered medical practitioner when; the pregnancy is the result of rape or incest, to protect the mental or physical health of the mother, or when there is a malformation of the fetus. The government of Ghana has taken steps to mitigate the negative effects of unsafe abortion by developing a comprehensive reproductive health strategy that specifically addresses maternal morbidity and mortality associated with unsafe abortion23.

Further, since midwives have been shown to safely and effectively provide post-abortion care in South Africa24 and Ghana19 a 1996 policy reform has allowed midlevel providers with midwifery skills to perform this service in Ghana25. To ensure these providers have the skills necessary to perform the service, in 2009, Manual Vacuum Aspiration (MVA) was added to the national curriculum for midwifery education to train additional providers in this life-saving technique.

However, even with the liberalization of the law and the training of additional providers, abortion-related complications remain a problem. This integrated literature review aims to present findings from empirical research directly related to abortion provision, complete abortion care, or post-abortion care in Ghana and identify gaps for future research.

Search Strategy

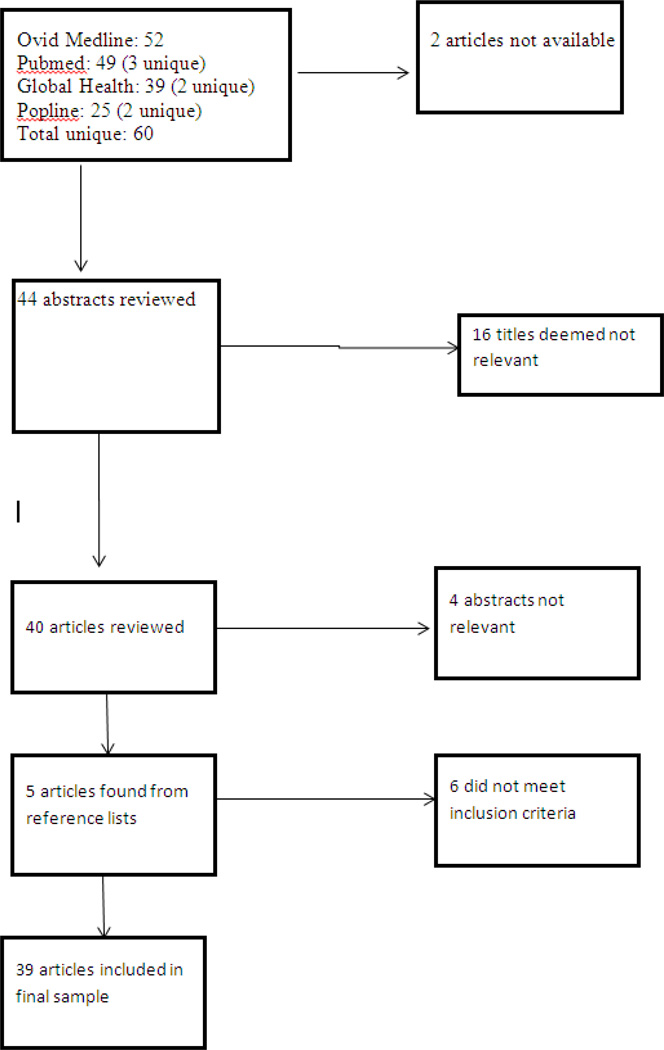

The Pubmed, Ovid Medline, Global Health and Popline databases were searched with the keywords “Ghana & abortion”. Pubmed returned 80 articles, Ovid Medline returned 70, Global Health returned 40 articles and Popline returned 78 articles, many of which overlapped. All titles and abstracts were reviewed. Inclusion criteria were: 1) English-language research articles; 2) published in a peer-reviewed journal after 1995; and 3) directly measured abortion services or provision. Manuscripts that only briefly mentioned abortion, commentaries, and literature reviews were not included in the final sample. A total of 39 articles met inclusion criteria and are included in this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Search results

Results

Complications and Admissions to Gynecology Ward

Abortion-related complications are repeatedly found to represent a large component of admissions to gynecological wards in hospitals in Ghana. Abortion complications resulted in 38.8%, 40.7%, 42.7% and 51%26–29 of all admissions to these wards in the articles reviewed for this paper. The majority of admissions were for the treatment of spontaneous abortion, although induced abortion is notoriously under-reported4, 12, 26, 30, and many women who reported spontaneous abortions had history that indicated induced abortion31. Sundaram and colleagues32 estimated that only 40% of abortions were reported in the 2007 Ghana Maternal Health Survey, even when participants were explicitly asked about their experiences with inducted abortions. Full results are provided in Table 1.

| Authors and Year |

Title, Journal | Findings | Study Design | Study Setting | Strengths and limitations | Database retrieved from |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Morhe ESK, Tagbor HK, Ankobea F, Danso KA. 2012 |

Reproductive experiences of teenagers in the Ejisu- Juabeng district of Ghana. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics |

Teenagers have their sexual debuts at young ages. 36.7% of the females have had at least one abortion. |

Cross-sectional survey community-based survey. |

Ejisu-Juabeng district of Ghana. |

There were no questions asked as to the processes undertaken to obtain abortions. |

Global Health, Popline |

| 2. Lee QY, Odoi AT, Opare-Addo H, Dassah ET. 2012 |

Maternal mortality in Ghana: a hospital- based review. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica |

Genital tract sepsis, often as a result of an abortion, had the highest case- fatality rate of all the causes of maternal death in this study. |

Secondary data analysis of patient charts |

Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital |

Comments are made that are not supported by data or references, such as, “Social stigma plays a role in preventing vulnerable women from accessing safe abortion services.” Reasons behind not accessing safe abortion services needs to be investigated. |

Reference List |

| 3. Ganyaglo GYK, Hill WC. 2012 |

A 6-year (2004-2009) review of maternal mortality at the East Regional Hospital, Koforidua, Ghana. Seminars in Perinatology |

Abortion complications were the second leading cause of maternal mortality, behind post-partum hemorrhage. The largest proportion of post-abortion deaths were due to sepsis (29 of the 37 post-abortion deaths). |

Secondary analysis of Obstetric and Gynecology ward admission and discharge books, triangulated against minutes from maternal death audit meetings and midwifery returns. Patient folders were available for 2009 only. |

Koforidua Regional Hospital, Eastern Region |

This is the first hospital-based study outside a major teaching hospital. |

Global Health |

| 4. Sundaram A, Juarez F, Bankole A, Singh S. 2012 |

Factors associated with abortion-seeking and obtaining an unsafe abortion in Ghana. Studies in Family Planning |

Almost half of all reported abortions were conducted unsafely. The profile of women who seek an abortion is: unmarried, in their 20s, have no children, have terminated a pregnancy before, are Protestant or Pentecostal/Charismatic, of higher SES, and know the legal status of abortion. Younger women were less likely to seek a safe abortion, as were women of low SES and those in rural areas. A partner paying for the procedure was associated with seeking a safe abortion. |

Nationally representative survey |

Maternal Health Survey | This study uses nationally- representative data to investigate safe and unsafe abortion seeking. However, abortion is under-reported, and there were no questions about unwanted pregnancy, or reasons for seeking safe versus unsafe abortions. |

Ovid Medline, Global Health PubMed |

| 5. Krakowiak- Redd D, Ansong D, Otupiri E, Tran S, Klanderud D, Boakye I, Dickerson T, Crookston B 2011 |

Family planning in a sub-district near Kumasi, Ghana: Side effect fears, unintended pregnancies and misuse of medication as emergency contraception. African Journal of Reproductive Health |

20% of the sample had had at least one abortion |

Cross-sectional community-based survey |

Barekese sub-district in the Ashanti Region |

A relatively small sample size (n=85) of only women. There was a qualitative component, but not about abortion-related issues. |

Global Health |

| 6. Aniteye P, Mayhew S. 2011 |

Attitudes and experiences of women admitted to hospital with abortion complications in Ghana. African Journal of Reproductive Health |

Great majority of women were young and single. The majority of women had help performing their abortion and most accessed post-abortion care at a health facility shortly after experiencing complications. |

Structured survey with 131 women with incomplete abortions. |

Gynecology ward, Korle Bu and Ridge Hospitals. |

The authors note a need for qualitative work especially around the reasons why women are not using family planning as well as to discover who the unsafe providers are. |

Ovid Medline, Global Health, PubMed, Popline |

| 7. Gumanga SK, Kolbila DZ, Gandau BBN, Munkaila A, Malechi H, Kyei-Aboagye K 2011 |

Trends in maternal mortality in Tamale Teaching Hospital, Ghana. Ghana Medical Journal |

The institutional maternal mortality rate was 1018 per 100,000 live births was recorded between 2006 and 2010. Complications from unsafe abortion was the leading cause of maternal death for youngest women, and the 4th leading cause overall. |

Hospital records from January 1 2006- December 2010. |

Tamale Teaching Hospital |

Documented the causes of maternal death in the Northern Region of Ghana. |

Global Health |

| 8. Biney AAE 2011 |

Exploring contraception knowledge and use among women experiencing induced abortion in the Greater Accra region, Ghana. African Journal of Reproductive Health |

Many respondents noted that prior to their induced abortion, they had no knowledge about contraception, but since the abortion they had been using it. Women also mentioned feeling contraception was more dangerous to their health than was induced abortion. |

24 semi-structured individual interviews were conducted with women who were being treated and reported having experience with induced abortion. |

Gynecology wards, Tema General Hospital and Korle Bu Teaching Hospital |

This study was mainly about contraception, and so access to abortion services were not investigated. |

Ovid Medline, Global Health, PubMed, Popline |

| 9. Ohene SA, Tettey Y, Kumoji R. 2011 |

Cause of death among Ghanaian adolescents in Accra using autopsy data. BMC Research Notes |

20/27 maternal deaths to adolescents were a consequence of abortion. |

Autopsy data | Korle Bu Teaching Hospital |

Demonstrated the burden of disease attributable to adolescent death |

PubMed |

| 10. Mac Domhnaill B, Hutchinson G, Milev A, Milev Y. 2011 |

The social context of school girl pregnancy in Ghana. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies |

Student’s knowledge of abortive methods was considerably more detailed than their knowledge of contraception. Many explicitly mentioned not using contraception because they knew how to abort a pregnancy if necessary. Participants note local and herbal methods of abortions, although they admitted they were dangerous. Abortion is seen by these participants as an unfortunate fact of being sexually active. |

Focus group discussions in both rural and peri- urban settings. |

Ho, Ghana | The focus-group methodology enables students to talk among themselves about sexual relationships. |

Global Health |

| 11. Schwandt HM, Creanga AA, Danso KA, Adanu RMK, Agbenyega T, Hindin MJ 2011 |

A comparison of women with induced abortion, spontaneous abortion and ectopic pregnancy in Ghana. Contraception |

N= 585. Majority reported spontaneous abortion between June and July 2008. Those with reported induced abortion were more likely to have more power in their relationships and to have not disclosed the index pregnancy to their partners. |

Surveys administered by nursing and midwifery students with women being treated for abortion complications. |

Gynecology emergency wards, Korle Bu and KATH. |

This is one of the only studies to look at male-female relationships and how these impact reproductive health decision making. |

Ovid Medline, Global Health, PubMed |

| 12. Mote CV, Otupiri E, Hindin MJ. 2010 |

Factors associated with induced abortion among women in Hohoe, Ghana. African Journal of Reproductive Health. |

One-fifth (21.3%) of respondents reported having had an induced abortion. Most common reasons for having an abortion: “not to disrupt education or employment” and “too young to have bear a child.” 65.5% performed by a medical doctor, 31% by partners or friends. 60.9% in a hospital, 29.9% at home. 50.6% used sharps or hospital instruments, 31% used herbs. |

408 community-based surveys |

Hohoe, Volta Region | Using community-based surveys gets a broader population than hospital-based. |

Global Health, PubMed |

| 13. Voetagbe G, Yellu N, Mills J, Mitchell E, Adu- Amankway A, Jehu-Appiah K, Nyante F. 2010 |

Midwifery tutors’ capacity and willingness to teach contraception, post- abortion care, and legal pregnancy termination in Ghana. Human Resources for Health |

Only 18.9% of the tutors surveyed knew all the legal indications under which safe abortion could be provided. These tutors were not taught manual vacuum aspiration during their training. |

74 midwifery tutors from all 14 public midwifery schools were surveyed. |

Midwifery training colleges country-wide |

74 of 123 selected tutors returned the survey, giving a response rate of 60.2%. Importantly documented the lack of complete knowledge of the law, even among midwifery tutors. |

PubMed |

| 14. Laar AK 2010. |

Family planning, abortion and HIV in Ghanaian print media: A 15-month content analysis of a national Ghanaian newspaper. African Journal of Reproductive Health |

This analysis showed that family planning, abortion and HIV received less than 1% of total newspaper coverage in one national Ghanaian newspaper. |

Content analysis of the Daily Graphic newspaper. |

Newspaper | This analysis shows that local speculations that the quantity and prominence of reproductive health issues are neglected in local newspapers are warranted. |

Global Health, PubMed |

| 15. Clark KA, Mitchell EHM, Aboagye PK 2010 |

Return on investment for essential obstetric care training in Ghana: Do trained public sector midwives deliver postabortion care? Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health |

The availability of PAC in Ghana remains limited. Far fewer midwives than physicians offer PAC, even after having received PAC clinical training, although an analysis of the curriculum and training was outside the scope of this study. |

Secondary data analysis of 2002 Ghana Service Provision Assessment survey. 428 health facilities working in 1448 health facilities were surveyed. |

Nationally- representative sample of health facilities and health providers |

Information about supplies available at the clinics, as well as whether the providers were offering CAC services, were not available in the dataset. |

Ovid Medline, PubMed, Popline |

| 16. Graff M, Amoyaw DA 2009 |

Barriers to sustainable MVA supply in Ghana: Challenges for the low-volume, low- income providers. African Journal of Reproductive Health. |

Sustainable access to MVA equipment has been challenging particularly for low-volume, low-income providers. Although many of the midwives in rural areas had the skills to provide MVA, they did not have the equipment and thus continued to refer women to district or regional hospitals. |

Interviews with 24 midwives and 16 physicians |

Data gathered in seven of the ten regions of the country. |

Interviews with a wide range of stakeholders is a major strength. |

Ovid Medline, Global Health, PubMed |

| 17. Hill ZE, Tawiah- Agyemang C, Kirkwood B. 2009 |

The context of informal abortions in rural Ghana. Journal of Women’s Health. |

Key themes were related to the perception of abortions as illegal, dangerous, and bringing public shame and stigma but also being perceived as common, understandable, and necessary. None of the respondents knew the legal status of abortion, with most reporting that it was illegal. |

Qualitative interviews in Kintampo, Brong-Ahafo. |

Ovid Medline, Global Health, MedLine |

||

| 18. Konney TO, Danso KA, Odoi AT, Opare-Addo HS, Morhe ESK. 2009 |

Attitudes of women with abortion-related complications toward provision of safe abortion services in Ghana. Journal of Women’s Health |

Abortion-related complications accounted for 42.7% of admissions to the gynecological ward at KATH, 28% of whom indicated an induced abortion. 92% of the women interviewed were not aware of the law regarding abortion in Ghana. Most felt that there was a need to establish safe abortion services in Ghana. |

Interviews of women being treated for abortion complications at KATH between May 1 and June 30, 2007. |

Gynecology ward at KATH |

The first study to investigate the attitudes of women being treated for abortion complications towards the provision of safe abortion services in Ghana. |

Ovid Medline, Global Health, PubMed, Popline |

| 19. Oliveras E, Ahiadeke C, Adanu RM, Hill AG 2008 |

Clinic-based surveillance of adverse pregnancy outcomes to identify induced abortion in Accra, Ghana. Studies in Family Planning. |

1,636 women completed the questions. Younger, better educated and unmarried women are more likely to have had an induced abortion. Between 10-17.6% of women report having had an abortion. Women seeking care at a private facility were more than twice as likely to have ended their previous pregnancy by induced abortion. |

Using previous birth technique, during prenatal care, nurses asked 5 questions to illicit how their previous pregnancy ended. |

Three public and two private clinics in Accra that provide antenatal and maternity services. |

Although this technique does not measure prevalence or lifetime exposure to abortion, it is another way to investigate abortion. Further work to elucidate differential responses based on healthcare provider asking is important. |

Ovid Medline, Global Health, PubMed, Popline |

| 20. Mills S, Williams JE, Wak G, Hodgson A 2008 |

Maternal Mortality Decline in the Kassena-Nankana District of Northern Ghana. Maternal and Child Health Journal |

Abortion-related deaths were the most frequent cause of maternal deaths in this sample in the Northern Region. |

Family members of all maternal deaths between January 2002 and December 2004 were interviewed |

Northern Region | Relying on verbal autopsy requires survivors to know of pregnancy status. There may have been more abortion- related deaths than reported if those interviewed did not know the woman was pregnant. |

Ovid Medline, PubMed, Popline |

| 21. Morhe ESK, Morhe RAS, Danso KA 2007 |

Attitudes of doctors toward establishing safe abortion units in Ghana. International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology |

Most physicians were supportive of playing some role in developing safe abortion units in hospitals in Ghana. However, only 54% of maternal and child health-related health workers were aware of the true nature of the abortion law, with 35% believing that the law permits abortion only to save the life of the woman. More than 50% of the workers reported they would be unwilling to play a role in performing pregnancy terminations. |

Cross sectional survey of 74 physicians at KATH |

Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital, Kumasi. |

The attitudes of health care providers is an important area to investigate due to the barriers these people can represent. |

Ovid Medline, Global Health, PubMed |

| 22. Adanu RMK, Ntumy MN, Tweneboah E. 2005 |

Profile of women with abortion complications in Ghana. Tropical Doctor |

31% of the study population presented for complications from induced abortion. Those seeking care for induced abortion were younger, or lower parity, more education, less likely to be engaged in income- generating activity, in less stable relationships and had more knowledge of modern contraception than those presenting for treatment from spontaneous abortion. |

Cross-sectional survey of 150 patients being treated for abortion complications. |

Korle Bu Teaching Hospital |

The determination of induced versus spontaneous abortion was reliant on self-report, which the authors note may be under-reported. |

Reference list |

| 23. Baiden F, Amponsa- Achiano K, Oduro AR, Mehsah TA, Baiden R, Hodgson A. 2006 |

Unmet need for essential obstetric services in a rural district northern Ghana: Complications of unsafe abortions remain a major cause of mortality. Public Health |

Complications from abortion were the leading cause of maternal mortality. Although abortion is considered taboo in NKD, according to clinic evidence, there is a high incidence of backstreet and unsafe practices. The district hospital did not have any access to formal safe abortion services. |

Secondary data analysis from chart review of all maternal deaths from January 2001 to December 2003 at the district hospital in Kassena-Nankana |

Kassena-Nankana district in the Northern Region |

Established abortion-related deaths are the leading cause of maternal deaths. Further research including all members of a woman’s community needs to be conducted to fully understand the social and cultural factors associated with seeking maternal healthcare. |

Ovid Medline, Global Health, PubMed, Popline |

| 24. Adanu RMK & Tweneboah E 2004 |

Reasons, fears and emotions behind induced abortions in Accra, Ghana. Research Review |

Women having induced abortion were younger, better educated, less likely to be married. 31.3% were reported to be induced abortion. Many who reported spontaneous abortion had stories that seemed to show induced. Most induced abortions were obtained outside the formal health system. |

Interviews with 150 women experiencing abortion complications. |

Gynecology ward, Korle Bu |

Only qualitative paper investigating the reasons behind and actions taken to terminate pregnancies. |

Reference list |

| 25. Yeboah RWN & MC Kom. 2003 |

Abortion: The case of Chenard Ward, Korle Bu from 2000 to 2001. Research Review |

The majority of admissions are due to incomplete abortions, although there were not classified by spontaneous or induced. Reported cases of induced abortions are high. |

Chart review of all abortion-related admissions between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2001; nurse interviews |

Gynecology emergency ward, Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana. |

No follow-up or interviewing of patients to determine reasons for abortion. |

Popline |

| 26. Glover EK, Bannerman A, Pence BW, Jones H, Miller R, Weiss E, Nerquaye- Tetteh J. 2003 |

Sexual health experiences of adolescents in three Ghanaian towns. International Family Planning Perspectives. |

35% of the female respondents reported ever being pregnant, and 70% of those reported having had or attempted an abortion. |

Community-based surveys of never-married youth about general sexual experiences. |

Tamale, Takoradi and Sunyani |

Using a community-based technique sampled previously under-represented groups. |

Global Health, PubMed, Popline |

| 27. Srofenyoh EK, Lassey AT 2003 |

Abortion care in a teaching hospital in Ghana. International Journal of Gyneaecology and Obstetrics |

30% of induced abortions had complications while 10% of spontaneous abortions had complications. 15% of maternal deaths over the study period were due to complications from abortion. Abortion complications were the leading cause of admission to the maternity ward (40.7% of all admissions). |

Chart review of all patients admitted to Korle Bu for abortion complications between January 1 and December 31, 2001. |

Gynecology ward, Korle Bu |

Important documentation of the burden of abortion complications at Korle Bu. |

Ovid Medline |

| 28. Geelhoed DW, Visser LE, Asare K, Schagen van Leeuwen JH, van Roosmalen J. 2003 |

Trends in maternal mortality: a 13-year hospital-based study in rural Ghana. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. |

Institutional maternal mortality rate of 1077 per 100,000 live births. Abortion complications were the leading cause (43 of the 229 deaths) |

Records from all maternal deaths between 1987 and 2000 were reviewed |

Berekum District hospital, Brong Ahafo Region |

Global Health, Popline |

|

| 29. Srofenyoh EK, Lassey AT 2003 |

Abortion care in a teaching hospital in Ghana. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics |

40% of admissions over the study period were related to abortion complications. Almost 77% were spontaneous abortions. 30% with induced abortion had serious complications while 10% of spontaneous abortion had similar complications. |

Retrospective chart review of all patients treated for abortion complications in 2000. |

Korle Bu Teaching Hospital |

Documents the high level of burden represented by abortion complications at Korle Bu. |

Ovid Medline, Global Health |

| 30. Turpin CA, Danso KA, Odoi AT 2002 |

Abortion at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital. Ghana Medical Journal |

Abortion complications accounted for 38.8% of admissions to the KATH Ob/Gyn ward in 1994. Induced abortions were more common in younger, unmarried women. The majority of induced abortions occurred in the 15-19 year old group. |

1,301 of 1,313 cases of abortion admissions to KATH were analyzed retrospectively. |

Obstetrics and Gynecology ward, Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital |

Established the large proportion of cases of post- abortion complications treated at KATH. Purely descriptive and reliant on information included in patient charts. |

|

| 31. Blanc A, Grey S. 2002 |

Greater than expected fertility decline in Ghana: Untangling a puzzle. Journal of Biosocial Science |

The total fertility rate in Ghana has declined at a higher rate than would be expected by the contraception prevalence rate. The authors find evidence of widespread abortion to control fertility, although accurate rates are hard to determine. The authors also note that the gap between expected fertility given contraception utilization and actual fertility is greater in urban areas than rural areas lends support to couples using abortion to limit or space births. |

Demographic and Health Surveys from 1988, 1993 and 1998. |

Representative sample. | As there are no reliable measures of abortion prevalence, the authors cannot rule out abortion being the reason behind the observed gap. Further, the authors note that abortion was, at the time or writing, illegal except to save the life of the mother or in the case of rape or incest. |

Popline |

| 32. Geelhoed DW, Nayembil D, Asare K, Schagen van Leeuwen JH, van Roosmale J. 2002 |

Gender and unwanted pregnancy: a community-based study in rural Ghana. Journal of Psychosocial Obstetrics and Gynecology |

Induced abortions were reported by 22.6% of the surveyed population. 28.2% of women reported having had an induced abortion. More women than med reported an unwanted pregnancy ending in abortion, perhaps signaling female independence in deciding on abortion care. |

2137 community -based surveys |

Berekum, Brong Ahafo Region. |

Interviewing both men and women gives a broader perspective. Questions investigating the process to obtain an abortion were not asked. |

Ovid Medline |

| 33. Ahiadeke C 2002 |

The incidence of self induced abortion in Ghana: What are the facts? Research Review. |

The rates identified here suggest that over a lifetime, 900 abortions per 1,000 women will be performed. The majority of women reported receiving their abortion from outside the formal healthcare system (30% from a pharmacist, 11% from self- medication, 16% from a “quack doctor” and 3% from other means). |

Data come from the cross-sectional community-based Maternal Health Survey in four regions |

These data come from before abortion policies were liberalized. |

Global Health |

|

| 34. Geelhoed D, Nayembil D, Asare K, Schagen JH, van Roosmalen J. 2002 |

Contraception and induced abortion in rural Ghana. Tropical Medicine and International Health. |

About 40% of participants had experienced an unwanted pregnancy in their lives. Socioeconomic reasons were the most common for why a pregnancy was unwanted |

Community-based surveys with 2137 participants |

Berekum District, Brong Ahafo Region |

Using anonymous, privately administered surveys yielded a high response rate. Interviewing both men and women is a strength. |

Ovid Medline, Global Health, Popline |

| 35. Ahiadeke 2001 |

Incidence of induced abortion in southern Ghana. International Family Planning Perspectives |

317/1,689 women aborted pregnancies (19/100, 27/100 live births, 17/1,000 women of reproductive age). Majority of women were under 30, married, Christian. Abortions happened outside the formal health sector. |

As part of Maternal Health Survey Project; 1,689 pregnant women were interviewed |

4 of the country’s 10 regions: Central, Eastern, Volta and Greater Accra. |

Community-based survey offers a different perspective than hospital-based, although further questions regarding the process are still necessary. |

Global Health |

| 36. Agyei WKA, Biritwum RB, Ashitey AG, Hill RB 2000 |

Sexual behaviour and contraception among unmarried adolescents and young adults in Greater Accra and Eastern Regions of Ghana. Journal of Biosocial Science |

A majority of the young adults surveyed were sexually experienced, although few were using contraception. Approximately 47% of those adolescents who had been sexually active reporting having had an abortion. While most participants were aware of modern methods of contraception, few used them. |

Fertility survey data with 953 males and 829 females. |

Greater Accra and Eastern regions |

Investigated the knowledge and practices of adolescents regarding their sexual health. Large community-based sample allows for generalization of findings. Due to quantitative nature, hard to establish the processes undertaken by pregnant girls to end their pregnancies or how many were safe versus unsafe. |

Ovid Medline |

| 37. Baird TL, Billings DL, Demuyakor B. 2000 |

Community education efforts enhance postabortion care program in Ghana. American Journal of Public Health |

Post-abortion care training for midwives was effective. Community- outreach was effective at educating the public about the new services being offered by midwives. |

Post-abortion care training for midwives to increase their skills, coupled with community outreach to educate women about where to access safe abortion services. |

Eastern Region. | No comprehensive evaluation of effectiveness was conducted. |

Ovid Medline, Public Health |

| 38. Obed SA & Wilson JB 1999 |

Uterine perforation from induced abortion at Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana: A five year review. West African Journal of Medicine |

21.1% of the 10,518 cases of abortion complication treatments for abortion were considered to be induced. 79 (3.6%) of those had uterine perforation. 40.9% (n=29) induced their abortion because they were not ready to have a baby, 36.6% (26) cited the index pregnancy being too close to previous deliver. 81% (64) reported wishing to have future children, although almost 1/3 of the patients had a hysterectomy to treat the complications. |

Prospective study of all patients being treated at Korle Bu for perforated uterus following an abortion (n=79) between 1990-1994. Patient interviews and chart review. |

Korle Bu Teaching Hospital |

Reference list |

|

| 39. Lassey AT 1995 |

Complications of induced abortion and their prevention in Ghana. East African Medical Journal |

58% of induced abortions were performed outside the health system and about 30% were complications from self-induced abortions using sticks, needles and herbal (often corrosive) inserted into the vagina. Only 9/212 were referrals, the rest were self-referred. |

Chart review of 200 patients admitted to the gynecology ward at Korle Bu for abortion complications. |

Gynecology ward, Korle Bu Teaching Hospital |

Data limited by being a chart review, although this early study highlighted the problem of unsafe abortion in the Greater Accra area. |

Ovid Medline |

Demographic Factors Associated with Abortion Care

Many studies investigated demographic factors associated with abortion-care seeking with conflicting results. Several manuscripts found women of higher socioeconomic status, with more education, who are married, older, and living in urban areas to be more likely to obtain induced abortions. However, others reported younger, unmarried women were more likely to obtain induced abortions, when compared to women seeking care for spontaneous abortion28, 31, 33–36.

Prevalence of Obtaining an Induced Abortion

The prevalence of obtaining an induced abortion varied greatly in the studies reported here. The highest rate reported was by Agyei and colleagues37 who found 47% of the female respondents in their study reporting at least one pregnancy underwent an abortion sometime in her life. Morhe et al.38 found 36.7 of the adolescents in their sample outside of Kumasi had experienced an abortion. Ahiadeke36, 39 reports an abortion rate of 27 per 100 live births using data from the Maternal Survey Project. Krakowiak-Reed et al.40 found 20% of their community-based sample outside Kumasi had had at least one abortion. Oliveras et al.34 found between 10% and 17.6% of women in their study reported their previous pregnancy ended in induced abortion. Geelhoed and colleagues41 found a prevalence of induced abortion of 22.6%, which falls in the range reported elsewhere42. Glover et al.43 found that 70% of ever-pregnant youth in their sample reported attempting an abortion. Sundaram et al.32 state approximately 10% of the sample for the 2007 Maternal Health Survey reported having had an abortion in the five years prior to the survey. However, the authors note that this rate is likely highly under-reported.

Abortion and Maternal Mortality

Many studies sought to estimate the proportion of maternal mortality associated with unsafe abortion. Mills and colleagues44 found abortion-related causes to be the leading cause of maternal death in rural northern Ghana, as did Baiden and colleagues10. Ohene et al.45 discovered that the majority of adolescent maternal deaths at Korle Bu Teaching Hospital in Accra were due to complications from unsafe abortion. Abortion complications were the leading cause of death among the youngest women in a sample of maternal deaths at Tamale Teaching Hospital, and the fourth leading cause overall45. Abortion complications were the second leading cause of death due to maternal causes, behind post-partum hemorrhage, between 2004–2009, a period which spans the introduction of the policy changes around abortion care, in the Eastern region47. Lee et al.48 discovered that genital tract sepsis, often as a result of an abortion, had the highest case-fatality rate of all the causes of maternal death in their study. In the Brong Ahafo region, Geelhoed et al. 41 found that abortion complications were the leading cause of maternal death at the Berekum District Hospital.

Abortion Law

Although the law governing abortion in Ghana is relatively liberal, and the 2006 policy change has made abortion services part of the national reproductive health strategy, no literature was found evaluating the impact of that policy change. The fact that admissions to the gynecological wards due to complications from abortion does not appear to have dramatically declined since the implementation of the 2006 policy suggests that women are not accessing safe abortion services, if they exist26, 49. Different cadres of health providers were found to be unsure of the law governing abortion services50, 51 and women who were interviewed were also unsure of the law26, 52. In the Brong Ahafo region, Hill and colleagues52 found that abortion was deemed illegal, dangerous and bringing public shame, but also being perceived as common, understandable, and necessary. Although Clark et al.25 found that post-abortion care (PAC) services remain limited, despite wide-spread training in the service, while Baird et al.53 report that PAC training for midwives is an effective way to increase access to the service. Including post-abortion care as part of comprehensive family planning training for midwives has the potential to empower these providers and the women they serve to make choices about contraception54. Graff & Amoyaw 11 identified sustainable access to MVA equipment as a major barrier to MVA services. Laar 55 found in an analysis of Ghanaian print media that less than 1% of total newspaper coverage was dedicated to family planning, abortion, and HIV, underscoring the dearth of information available to many in the Ghanaian public.

Abortion and Contraception

One of the main findings in many of the papers reviewed is the lack of modern contraception being used by the majority of Ghanaian women. Many of the papers found a high unmet need for contraception defined as currently engaging in sexual activity without using contraception but without intending to get pregnant9,32, 33, 56. There is an urgent need to improve access to reliable contraception for Ghanaian women. Many Ghanaian women report being wary of using contraception for fear of side effects that may impair future fertility9. Biney56 noted that women in her study viewed contraception as more harmful to their health than abortion. Obed & Wilson57 reported 81% of their sample of women being treated for abortion complications desired further children, although almost one-third had to have a hysterectomy to treat the complications from their abortion and were thus unable to have further children. Mac Domhnaill and colleagues58 found schoolgirls in their sample were much more aware of abortion methods than of contraception and many explicitly mentioned not using contraception because they knew how to abort if necessary. Adanu and colleagues33 reported women seeking care for induced abortion were more aware of modern contraception than their counterparts seeking care for spontaneous abortion, although this did not translate into higher usage rates.

Identified Gaps for Further Research

The biggest gaps identified through this review are the experiences of women with securing an induced abortion to end an unwanted pregnancy. Hospital-based chart reviews are important to understand the types of cases being treated. Surveys examining the reasons for securing an induced abortion shed some light on this issue. However, information regarding the process by which a woman seeks an induced abortion is still lacking. Gathering information from women regarding their experiences securing safe and legal abortions and reasons for resorting to unsafe methods will enable policy makers to pinpoint interventions to prevent life-threatening complications. Specifically, why do women resort to dangerous methods of aborting unwanted pregnancies?

Discussion

Complications from unsafe abortion have been and remain a large component of maternal mortality and morbidity in Ghana. Although responding to international calls to liberalize the law governing abortion and training more providers in the service, Ghana has not yet realized a large reduction in complications from unsafe abortions. Knowledge of the law appears to remain limited, among both healthcare providers and the general population. Work to improve this is warranted.

There appears to be a robust literature around abortion in Ghana. However, this review did identify gaps in the literature and future directions for research. The heavy reliance on hospital-based retrospective chart reviews, while an important step to establish the general burden of disease attributable to abortion-related complications, needs to be expanded. The studies completed were generally of a high scientific standard, although the data were often limited by what was documented in charts or log books. The few purposefully-designed surveys elucidated interesting observations that need to be augmented by qualitative work to answer some of the deeper questions of the process by which women undertake unsafe abortions. It has been documented that many women are seeking care outside59 the formal healthcare system in unsafe locations from unsafe providers33, however reasons why have not been investigated. Is it a lack of awareness of the legality of this procedure? Are there not enough providers in communities close to where the women live? Is cost prohibitive? Both women seeking care for post-abortion care and providers of abortion have been shown to be unclear of the law governing abortion in Ghana. Konney et al.26 found 92% of women being treated for abortion complications at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital were unaware of the law and Voetagbe et al. 51 noted an alarmingly high proportion of midwifery tutors were not aware of the full law governing the provision of safe abortion services. If teachers are not sure of the law, the midwives who they train will also likely be uncertain of the conditions under which they are legally allowed to provide complete abortion care.

Accessibility of abortion care was defined by Billings et al. 19 as 1) distance from a woman’s home; 2) cost of services and payment options; 3) waiting time for services / total length of stay; and 4) social proximity to the provider. All of these accessibility issues require further investigation, with an operations-research design that could address many of them.

The repeated finding of the high incidence of abortion complications and resulting hospitalizations in the tertiary care centers, as well as some smaller district-level hospitals in the country, highlights the need to adequately train providers to treat complications resulting from abortions, whether these abortions are spontaneous or induced. Assessing the ability of public hospitals to safely provide treatment for post-abortion complications, as well provide a safe and affordable place for women to access comprehensive abortion care, is necessary. Women in urban areas appear to have greater access to safe abortion services, although the availability country-wide has not been assessed. The government of Ghana has responded to the need to provide treatments for post-abortion complications by recently adding training in MVA to the curriculum of midwifery training colleges. An assessment to assure midwives are graduating knowing how to handle these complications will be a necessary next step to ensure the safety of Ghanaian women who suffer from post-abortion complications.

Although demographic differences were found in many of the papers, it is conceivable the differences found could be explained by selection bias, as most of the studies reporting this information are hospital-based surveys conducted at the large referral centers, either Korle Bu in Accra or Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital in Kumasi. Women in rural areas without the means to travel to and be treated at these tertiary care centers will therefore not be included in the sample. It is unclear from these studies whether the differences reported are due to differences in sampling techniques and survey populations or to true differences in the need for abortion services. In the 2007 Maternal Health Survey, as reported by Sundaram and colleagues32, which is nationally representative, women in their twenties who have never been married, have no children, have terminated a pregnancy before, are Protestant or Pentecostal/Charismatic, of higher SES, and know the legal status of abortion are more likely to seek an abortion. Further, they found younger women were less likely to seek a safe abortion, as were women of low SES and those in rural areas. A partner paying for the procedure was associated with seeking a safe abortion.

The repeated findings of how few women are using contraception both preceding and following an abortion are worrisome. There is an urgent need to improve access to reliable contraception for Ghanaian women. However, the results from many studies indicate simply improving access to modern contraception may not improve utilization if women are more afraid of the side effects of contraception than of complications from unsafe abortion 9, 56. This fear is ironic considering the very real negative health implications that follow unsafe abortions. Those who know more about contraception were found not to be more likely to use it, suggesting that simply providing information does not seem adequate to substantially increase usage33.

Although not directly investigated in the studies reported here, unfamiliarity with the legal status of abortion appears to be a driver of women seeking care in unsafe locations outside the formal healthcare system. Future work needs to be done to evaluate the best ways to educate health workers and the public on the law and availability of services. Qualitative work interviewing healthcare providers, policymakers, and community members to elucidate interventions to improve the provision of safe abortion services and post-abortion care is necessary. Billings and colleagues19 note that to understand the role midwives can play in providing safe abortion, further research should be conducted at the community level. Hill and colleagues51 suggest purposefully designing qualitative studies to assess the perceptions of healthcare workers towards providing safe abortion services, as well as asking participants to report on friends’ use of abortion services to determine rates. Aniteye and Mayhew9 recommend qualitative work with women undergoing treatment for abortion complications to elucidate reasons they are not using family planning methods.

Conclusion

The government of Ghana has made the important initial steps of reducing legal barriers to safe abortion services and increasing the training of qualified personnel30 in order to reduce the burden of disease attributable to unsafe abortion. However, complications from unsafe abortion are still a large contributor to women’s mortality and morbidity. Future work is needed to investigate barriers that prevent women from accessing safe abortion services and to ensure that Ghanaian women have access to safe abortion as fully allowed by the law.

Footnotes

Contribution of Authors

SR conceptualized the research and performed the initial searches. JR reviewed search results. SR wrote the first draft of the manuscript. JR edited the manuscript. Both authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) Safe abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems. 2nd ed. Geneva: WHO; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO) Unsafe abortion. Global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2000. 4th ed. Geneva: WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh S. Hospital admissions resulting from unsafe abortion: estimates from 13 developing countries. Lancet. 2006;368(95550):1887–1892. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69778-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah I, Ahman E. Unsafe abortion: global and regional incidence, trends, consequences and challenges. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology Canada. 2009;31(12):1149–1158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization (WHO) Unsafe abortion. Global and regional estimates of incidence of and mortality due to unsafe abortion with a listing of available country data. 3rd ed. Geneva: WHO; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aahman E, Shah I. Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2000. 4th edition. Geneva: WHO; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2003. Geneva: WHO; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aniteye P, Mayhew S. Attitudes and experiences of women admitted to hospital with abortion complications in Ghana. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2011;15(1):47–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baiden F, Amponsa-Achiano K, Oduro AR, Mehsah TA, Baiden R, Hodgson A. Unmet need for essential obstetric services in a rural district hospital in northern Ghana: complications of unsafe abortions remain a major cause of mortality. Journal of the Royal Institute of Public Health. 2006;120(5):421–426. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graff M, Amoyaw DA. Barriers to sustainable MVA supply in Ghana: challenges for the low-volume, low-income providers. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2009;13(4):73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lithur NO. Destigmatizing abortion: expanding community awareness of abortion as a reproductive health issue in Ghana. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2004;8(1):70–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu D, Grossman D, Levin C, Blanchard K, Adanu R, Goldie SJ. Cost-effectiveness analysis of unsafe abortion and alternative first-trimester pregnancy termination strategies in Nigeria and Ghana. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2010;14(2):85–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Facts on induced abortion Worldwide. World Health Organization. Geneva: Department of Reproductive Health and Research; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Global Health Observatory. [July 23, 2013];2009 Accessed from http://www.who.int/countries/gha/en/

- 16.Ghana: UNICEF Country Statistics; [January 9, 2014]. Accessed from http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/ghana_statistics.html. [Google Scholar]

- 17.The State of World's Midwifery 2011: Delivering Health, Saving Lives. UNFPA; 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asamoah BO, Moussa KM, Stafstrom M, Musinguzi G. Distribution of causes of maternal mortality among different socio-demographic groups in Ghana; a descriptive study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:159. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Billings DL, Ankrah V, Baird TL, Taylor JE, Ababio KPP, Ntow S. Midwives and comprehensive postabortion care in Ghana. In: Huntington and Piet-Pelon, editor. Postabortion Care: Lessons from Operations Research. New York, New York: Population Council; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eades CA, Brace C, Osei L, LaGuardia KD. Traditional birth attendants and maternal mortality in Ghana. Soc. Sci. Med. 1993;36(11):1503–1507. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90392-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sedge G. Brief. 2. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2010. Abortion in Ghana. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morhe RAS, Morhe ESK. Overview of the law and availability of abortion services in Ghana. Ghana Medical Journal. 2006;40(1):80–86. doi: 10.4314/gmj.v40i3.55256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor J, Diop A, Blum J, Dolo O, Winikoff B. Oral misoprostol as an alternative to surgical management for incomplete abortion in Ghana. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2011;112:40–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sibuyi MC. Provision of safe abortion services by midwives in Limpopo Province of South Africa. Afr J Reprod Health. 2004;8(1):75–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clark KA, Mitchell EHM, Aboagye PK. Return on investment for essential obstetric care training in Ghana: do trained public sector midwives deliver postabortion care? Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2010;55(2):153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jmwh.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konney TO, Danso KA, Odoi AT, Opare-Addo HS, Morhe ESK. Attitude of women with abortion-related complications toward provision of safe abortion services in Ghana. J Womens Health. 2009;18(11):1863–1866. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Srofenyoh EK, Lassey AT. Abortion care in a teaching hospital in Ghana. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2003;82:77–78. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7292(03)00033-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Turpin CA, Danso KA, Odoi AT. Abortion at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital. Ghana Medical Journal. 2002;36(2):60–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeboah RWN, Kom MC. Abortion: The case of Chenard Ward, Korle Bu from 2000 to 2001. Research Review. 2003:57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cohen SA. Access to safe abortion services in the developing world: Saving lives while advancing rights. Guttmacher Policy Review. 2012;15(4):2–6. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adanu RMK, Tweneboah Reasons, fears and emotions behind induced abortions in Accra, Ghana. Research Review. 2004;20(2):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sundaram A, Juarez F, Bankole A, Singh S. Factors associated with abortion-seeking and obtaining a safe abortion in Ghana. Studies in Family Planning. 2012;43(4):273–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adanu RMK, Ntumy MN, Tweneboah E. Profile of women with abortion complications in Ghana. Tropical Doctor. 2005;35(3):139–142. doi: 10.1258/0049475054620725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oliveras E, Ahiadeke C, Adanu RM, Hill AG. Clinic-based surveillance of adverse pregnancy outcomes to identify induced abortions in Accra, Ghana. Studies in Family Planning. 2009;39(2):133–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwandt HM, Creanga AA, Danso KA, Adanu RMK, Agbenyega T, Hindin MJ. A comparison of women with induced abortion, spontaneous abortion and ectopic pregnancy in Ghana. Contraception. 2011;84(1):87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahiadeke C. The incidence of self-induced abortion in Ghana: What are the facts? Research Review. 2002;18(1):33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agyei WKA, Biritwum RB, Ashitey AG, Hill RB. Sexual behavior and contraception among unmarried adolescents and young adults in Greater Accra and Eastern Regions of Ghana. Journal of biosocial Science. 2000;32(4):495–512. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000004958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morhe ESK, Tagbor HK, Ankobea F, Danso KA. Reproductive experiences of teenagers in the Ejisu-Juabeng district of Ghana. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2012;118(2):137–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ahiadeke C. Incidence of induced abortion in Southern Ghana. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2001;27(2):96–108. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krakowiak-Redd D, Ansong D, Otupiri E, Tran S, Klanderud D, Boakye I, Dickerson T, Crookston B. Family planning in a sub-district near Kumasi, Ghana: Side effect fears, unintended pregnancies and misuse of medication as emergency contraception. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2011;15(3):121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Geelhoed DW, Nayembil D, Asare K, Schagen van Leeuwen JH, van Roosmale J. Contraception and induced abortion in rural Ghana. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 2002;70(8):708–716. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mote CV, Otupiri E, Hindin M. Factors associated with induced abortion among women in Hohoe, Ghana. African Journal of Reproductive Helath. 2010;14(4):115–121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Glover EK, Bannerman A, Pence BW, Jones H, Miller R, Weiss E, Nerquaye-Tetteh J. Sexual health experiences of adolescents in three Ghanaian towns. International Family Planning Perspectives. 2003;29(1):32–40. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.29.032.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mills S, Williams JE, Wak G, Hodgson A. Maternal mortality decline in the Kassena-Nankana district of northern Ghana. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2008;12:577–585. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0289-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ohene SA, Tettey Y, Kumoji R. Cause of death among Ghanaian adolescents in Accra using autopsy data. BMC Research Notes. 2011;12(4):353. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-4-353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gumanga SK, Kolbila DZ, Gandau BBN, Munkaila A, Malechi H, Kyei-Aboagye K. Trends in maternal mortality in Tamale Teaching Hospital, Ghana. Ghana Medical Journal. 2011;45(3):105–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ganyaglo GYK. A 6-year (2004–2009) review of maternal mortality at the Eastern Regional Hospital, Koforidua, Ghana. Seminars in Perinatology. 2012;36(1):79–83. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee QY, Odoi AT, Opare-Addo H, Dassah ET. Maternal mortality in Ghana: a hospital-based review. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2012;91(1):87–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Henaku RO, Horiuchi S, Mori A. Review of unsafe / induced abortions in Ghana: Development of reproductive health awareness materials to promote adolescents health. Bulletin of St. Luke's College of Nursing. 2007;33(3):93–102. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morhe ES, Morhe RA, Danso KA. Attitudes of doctors towards establishing safe abortion units in Ghana. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2007;98(1):70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Voetagbe G, Yellu N, Mills J, Mitchell E, Adu-Amankway A, Jehu-Appiah K, Nyante F. Midwifery tutors’ capacity and willingness to teach contraception, post-abortion care, and legal pregnancy termination in Ghana. Human Resources for Health. 2010;8(2) doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hill ZE, Tawiah-Agyemang C, Kirkwood B. The context of informal abortions in rural Ghana. Journal of Women’s Health. 2009;18(12):2017–2022. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baird TL, Billings DL, Demuyakor B. Community education efforts enhance postabortion care program in Ghana. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(4):631–632. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.4.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fullerton J, Fort A, Johal K. A case/comparison study in the Eastern region of Ghana on the effects of incorporating selected reproductive health services on family planning services. Midwifery. 2002;19:17–26. doi: 10.1054/midw.2002.0334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Laar AK. Family planning, abortion and HIV in Ghanaian print media: A 15-month content analysis of a national Ghanaian newspaper. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2010;14(1):80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Biney AAE. Exploring contraceptive knowledge and use among women experiencing induced abortion in the Greater Accra region, Ghana. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2011;15(1):37–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Obed SA, Wilson JB. Uterine perforation from induced abortion at Korle Bu Teaching Hospital, Accra, Ghana: A five year review. West African Journal of Medicine. 1999;18(4):286–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mac Domhnaill B, Hutchinson G, Milev A, Milev Y. The social context of schoolgirl pregnancy in Ghana. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2011;6(3):201–207. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lassey AT. Complications of induced abortions and their preventions in Ghana. East African Medical Journal. 1995;72(12):774–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]