Abstract

As countries develop economically and increasing numbers of women enter the workforce, children are partly being cared for by someone other than their mother. Little is known about the impact of this shift in child-care provider on children’s nutrition. This study presents findings from a case study of Singapore, a small country that has experienced phenomenal economic growth. Focus groups were conducted with 130 women of varying educational levels and ethnicities to learn about food decisions in their families. The findings showed that Singaporean working women cook infrequently, families eat out frequently, and children exert considerable influence on food choices. Implications for work–family policies and child health are discussed.

Keywords: family, food decisions, child nutrition, Singapore, urbanization

In this article, we present a case study of how women’s role as the primary provider of food for young children, a critical aspect of child care, has changed in Singapore, a newly industrialized nation known for its highly successful economic-development policies. This study shares findings from focus groups conducted with 130 Singaporean women to understand how decisions relating to food purchasing, preparation, and consumption are made for themselves and their families. The motivation for writing this article is to promote research interest in (a) addressing the issues families face in providing optimal nutrition to their children and nurturing healthy eating habits as increasing numbers of women join the labor force, and delegate the task of child care to others; and (b) developing effective work–family policies that promote gender equality as well as healthy families.

THE CONTEXT

With a total area of no more than 275 square miles and an ethnically diverse population of over 5 million people (Chinese, Malay, Indian, Eurasian, and others), Singapore is one of the most densely populated and wealthiest countries in the world. Government policies to stimulate economic development initiated in the 1960s and 1970s, which included providing educational opportunities for all Singaporeans regardless of gender, have been highly successful (Pyle 2001). As more Singaporean women became better educated and entered the workforce, fertility rates began to decline (Lim 2002); from 1970 to 2006, Singapore’s fertility rate fell by 60%, from an average of 3.07 to 1.26 children per woman (Westley, Choe, and Rutherford 2010). Today, Singapore has one of the lowest fertility rates in the world (Central Intelligence Agency 2013).

Singapore is one of four Asian countries that have experienced some of the steepest declines in fertility in history, the others being Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. Surveys of women in these countries show that most young women would like to start a family (Lee, Alvarez, and Palen 1991; Westley et al. 2010); however, with the expanded opportunities to continue their education and develop their careers, they are marrying later or not marrying at all. Increasing social acceptance of premarital sex and the cost of raising a family (including the opportunity cost for the woman who interrupts her career to give birth) are further deterrents to marriage and having children (Call et al. 2008; Westley et al. 2010).

From an economic-policy perspective, having low fertility rates below replacement levels is worrisome because of the burden on the public pension and health-care systems posed by an increasing elderly population. As a result, countries such as Singapore have been experimenting with policies to increase fertility rates by offering incentives to couples to marry and have children (Webb 2006). Since 2000, Singapore has implemented incentives such as longer paid maternity leave, maternity leave protection, and leave for child care (which was previously non-existent) in an effort to reverse the declining trend in fertility. Additionally, the Work-Life Works program was established in 2004 to encourage private-sector organizations to implement measures to help employees achieve work–life harmony. Despite these efforts, fertility rates have continued to decline. Findings from a recent study suggest that Singaporean women continue to be concerned about workplace rights with regard to taking leave for child-care reasons (Sun 2009). The past three decades have seen increasing numbers of Singaporean children being cared for by child-care institutions, and “foreign domestic workers” (Teo 2010).

As more mothers began to work in the 1970s, domestic workers, who were increasingly recruited from lesser-developed neighboring countries where wages were lower, began to fill the role of child-care provider. When available, grandparents helped by caring for young children or by supervising domestic workers who mostly came from the Philippines, Indonesia, Myanmar, Thailand, Sri Lanka, and India (Yeoh, Huang, and Gonzalez 1999). From 1987 to 2010, Singapore saw more than an eightfold increase in the number of families who hired domestic workers. Today, one in six Singaporean households hires a domestic worker to help care for children or the elderly (Wong 2008). Additionally, the number of child-care centers grew by over 40%, from 558 in 2000 to 794 in 2010 (Khoo 2010). These trends imply that domestic workers and child-care centers have increasingly become the direct providers of food for young children for at least one if not all meals in a day. As domestic workers and child-care centers become increasingly involved in the provision of food to young children, how are decisions made regarding what young children eat? This study attempts to answer this question by examining the responses of 130 Singaporean women who participated in focus groups conducted for the primary purpose of providing information to guide the planning of obesity-related interventions. Relevant to this article, these focus groups sought to understand how food-related decisions are made by women of varying educational levels, from the major ethnic groups in Singapore.

METHODS

A purposeful sample of 130 Singaporean women aged 30 to 55 years from the three major ethnic groups in the country (i.e., Chinese, Indian, and Malay) and of varying educational levels (i.e., “O” level or less, and “A” level or higher1) participated in 18 focus groups conducted in 2011. The women were recruited by telephone invitation from a list of participants of the Singapore Consortium of Cohort Studies (http://www.nus-cme.org.sg/) who had indicated they were interested in learning about future research studies; this list provided not only contact information but also demographic information citing participants’ gender, ethnicity, education, and age, allowing for the selection of a sample of women who met the predefined age requirement, and that was roughly equally distributed by ethnicity and education. Participants were informed of the purpose and requirements of the study during the telephone invitation, and in writing through a “Participant Information Sheet” given at the beginning of the focus group sessions. They were also informed that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time. Informed consent was obtained from the participants who were compensated for their time and travel expenses. The study protocol was approved by the National University of Singapore’s Institutional Review Board (approval no. NUS 1330).

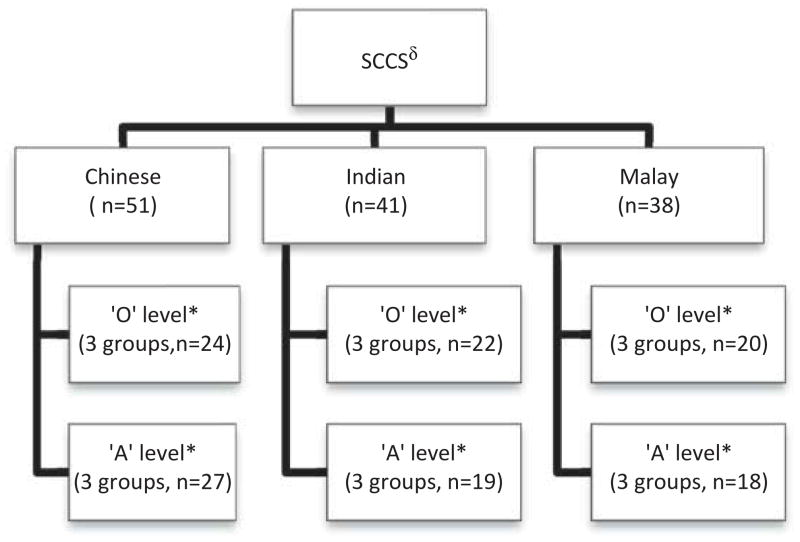

The 130 women were assigned to 6 groups of similar ethnicity and educational level: more highly educated (i.e., “A” level or higher2) Chinese, Indian, or Malay, and less highly educated (i.e., “O” level or lower) Chinese, Indian, or Malay. Participants assigned to each of these 6 groups took part in 1 of 3 focus group sessions; a total of 18 focus group sessions were conducted, with 5 to 9 people participating in each. See figure 1 for the assignment of participants to focus groups.

FIGURE 1.

Recruitment and assignment of participating women to focus groups.

δ Singapore Consortium of Cohort Studies (http://www.nus-cme.org.sg/)

*3 groups, each comprising 5 to 9 participants.

The 18 focus group sessions, 90 minutes each, were conducted by hired moderators fluent in English and the ethnic language of their assigned group participants, providing a total of 27 hours of discussion. A semi-structured focus-group guide was developed, and included questions designed to capture a broad range of information helpful for planning obesity-related interventions. The Theory of Triadic Influence, which considers intrapersonal, interpersonal, social, and cultural environmental influences on health behaviors (Flay and Petraitis 1994), provided the conceptual framework for the development of the focus-group guide. Hence, questions were developed assuming that individual food choices and eating decisions are formulated within social and cultural environmental contexts (Flay and Petraitis 1994; Sobal and Bisogni 2009). Specifically, the questions focused on (1) how food choices are made, (2) how food is acquired, (3) who prepares meals, (4) what are perceived to be healthy and unhealthy foods, and (5) perceptions of what causes obesity. (For the purposes of this study, only responses that were relevant to food decisions were examined.) Two members of the research team were involved in the development of the guide, which allowed for a priori codes to be developed based on the biological, social, and cultural environmental domains, with additional codes added during the analysis. The protocol also included the administration of a brief close-ended questionnaire which asked for birth date, highest educational level, and the height and weight of each participant, to describe characteristics that may influence the responses of each focus group.

Focus-group sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed into the language used by the participants (which was often English); when the spoken language was not English, the transcript was later translated into English. Professional bilingual Chinese–English, Malay–English, and Tamil–English translators were involved in the respective transcriptions from the audio recordings and translation into English. Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and translated into English where necessary. All sessions were back-translated, and several were reviewed by the research team as a quality-control measure.

Three members of the team independently coded the transcripts to identify themes and patterns. One, an anthropologist, used an inductive iterative process, while two used the qualitative data-management software ATLAS.ti version 6.2.23 (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany), based on a priori themes (Flick 2009). A fourth member reviewed the coded transcripts to specifically identify trends, patterns, and themes relevant to the role of women in providing food for their children and in influencing food decisions affecting their children’s food-consumption behaviors. Each of the 18 transcripts was read at least once by the research team prior to coding. All team members came together to discuss findings; when there were inconsistencies, the transcripts were re-coded. Participants’ comments quoted in this article are translated from “Singlish,” a form of English that is commonly spoken by Singaporeans (Deterding 2007). Two of the team members were native Singaporeans and were fluent in Singlish, and at least one of the four researchers analyzing the data was conversant if not fluent in each of the local languages—Malay, Tamil, and Chinese (Mandarin and local Chinese dialects).

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

In Table 1 we provide summary characteristics, namely, age and education of the participants by ethnicity. The mean (± SD) age of the participants was 46.1 (± 7) years. About 15% had less than 4 years of secondary school education; 36% had attended 4 years of secondary school, with most obtaining the “O” level certificate; 36% had obtained the “A” level certificate or held a diploma; and 13% had at least an undergraduate degree. Although an effort was made to recruit a sample of women who did not differ substantially in educational level among the three ethnic groups, differences were apparent. In particular, Chinese and Malay participants were more likely to have received a college degree than were Indian participants.

TABLE 1.

Summary Characteristics of Focus Group Participants by Ethnicitya

| Chinese (n = 51) | Malay (n = 38) | Indian (n = 41) | Total (N = 130) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years)b | 45.9 ± 7.7 | 44.1 ± 6.6 | 48.2 ± 6.1 | 46.1 ± 7.0 |

| Educationc | ||||

| < 4 years of secondary school | 4 (7.8%) | 5 (13.2%) | 10 (24.4%) | 19 (14.6%) |

| 4 years of secondary school/“O” level | 20 (39.2%) | 15 (39.5%) | 12 (29.3%) | 47 (36.2%) |

| “A” level/diploma | 20 (39.2%) | 12 (31.6%) | 15 (36.6%) | 47 (36.2%) |

| University degree or higher | 7 (13.7%) | 6 (15.8%) | 4 (9.8%) | 17 (13.1%) |

| Total | 51 | 38 | 41 | 130 |

Selected to include Chinese, Malay, and Indian women of varying educational levels.

Mean ± SD.

Numbers represent frequency and percent distribution within each ethnic group, n (%).

Focus-Group Findings

Two broad themes emerged from the analysis of the focus-group transcripts with regard to the role of Singaporean women as the primary provider of food necessary for their children’s growth and development:

Women in Singapore cook less today than their mothers did

For many families, food decisions are driven by the children

Under these broad themes, were sub-themes, which are discussed below.

WOMEN IN SINGAPORE COOK LESS TODAY THAN THEIR MOTHERS DID

Employment presents a barrier to cooking

In all of the focus groups, there was mention of how often families eat out, and how infrequently women cook at home today. Some women noted that more women work today than in the past. Others were of the opinion that employment makes it difficult for women to cook, and predicted that with the increasing numbers of women working, fewer women will cook or know how to cook, alluding to a generational effect. Some women implicitly assumed that women who stay at home must cook, and that those who work cannot be expected to find time to cook:

But in the past, women hardly went out to work. My mum doesn’t work and she is at home most of the time so it is her job to cook. (CH3)3

The generation will be eating out at all meals, like me now. I am already eating out at all meals. (CH3)

I think they [the next generation] won’t have time to cook. (CH3)

Children’s after-school enrichment activities limit time for meal preparation

Other than work, having children is itself a deterrent to cooking, as the mothers are busy transporting the children to school activities and enrichment classes after school on weekdays and during the weekend:

Even on Saturdays and Sundays, we are busy fetching the kids to and from classes, so we don’t cook, and we end up eating out. (IH2)

Ready availability of cheap, affordable prepared food provides an alternative to cooking

Some women noted that the ready availability of affordable food in hawker centers4 and food courts is a disincentive for women to cook. Others noted that eating out can be cheaper than preparing meals at home:

Moreover, cooking is not cheap. Sometimes it is cheaper to eat out than to cook at home. (CH3)

Sometimes it is convenience…. If you don’t cook and you eat out, the nearest place will be the hawker center. (CH2)

Acknowledgement that eating at home is healthier and more hygienic

A few women indicated that they preferred to eat home-prepared food because it is healthier and more hygienically prepared, and they have more control over the use of unhealthy condiments such as monosodium glutamate (MSG):

I think home-cooked food is healthier. In fact, my brother-in-law is a cook, and he told me that they add MSG to hor-fun (a rice-based Chinese noodle dish). In fact, why every food is so tasty is because they add MSG. At home, of course, we don’t do that. It’s not like we totally don’t eat out—we do—but it just happens once in a while, like once a week. (IH2)

When we eat outside, sometimes the stall is clean, sometimes it’s not clean. Sometimes, you see children eating out and getting diarrhea. My house is clean. Once a week, I don’t cook—every Friday we eat out. Other than that, for the remaining six days, I stay at home. (IL3)

Affordable domestic workers support women with children

Several women who preferred home-prepared food shared that domestic workers (commonly referred to as “maids”) helped prepare meals for their families on weekdays when they work. Sometimes the domestic workers decide what food is prepared, while in some cases the women themselves are the decision makers:

I think I’m more into healthy food as well. Once in a while as a family, we’ll go out. My husband likes to eat out at times …he’ll just go with his colleagues or friends to eat out…. For me and my kids, we don’t eat out too much …we use more healthy oil. They [the kids] complain [about the food] because the maid sometimes cooks, you know? Normally, I cook on the weekend. On weekdays, I’ve no choice. I have to leave the cooking for the maids to do. So if I am around, then I’ll do the cooking. Basically, it’s healthier. (IH2)

Sometimes you tell the maid, the maid doesn’t listen also. (CH1)

Moderator: Follow the recipes? So will you be the one to decide what to buy or will you let your maid decide?

Participant: I am the one who decides. (CH1)

Ethnic differences in women’s attitude towards cooking

Malay women were more likely to voice that they cooked at home and that their husbands expected to have home-prepared meals. However, as for other Singaporean women, work is also a barrier to cooking for Malay women. For example, women who work shifts may cook only on their “off” days:

Because my husband doesn’t like to eat out, that’s why I have to cook. No matter how, I have to cook. (ML1)

I work 12-hour shifts. I have three days off, and two days of work. On my work days, I seldom cook. There is only my husband and me, so we prefer to eat out rather than cook at home. But on my off days, I will cook for all. I will cook asam pedas, or lemak dishes (dishes with coconut milk). There are vegetables in those dishes …salads, cucumbers, mixed vegetables. (ML2)

FOR MANY FAMILIES, FOOD DECISIONS ARE DRIVEN BY THE CHILDREN

Children’s food preferences influence their mothers’ food decisions for the family

In all focus groups, women with children voiced that their children were highly influential in determining the foods their families ate. Some alluded to the varying food preferences of family members and their efforts to meet these preferences:

What I buy is what they [the children] like; and the maid will cook for them. (CH1)

Women try to meet the food preferences of all members of the family

When they cook, women may try to meet the varying food preferences of their family members by rotating the favorite dishes of individual family members across meals:

And then I will just eat whatever. Because I make everybody happy …the father would say, “I would like Chin Char Rot” (pickled seafood dish) …but my son hates Chin Char Rot…. Then my girl would like soup, but my son never likes soup…. So I can’t please everybody…. Tomorrow I will please my son…. Yah, I will take turns …it is just impossible to satisfy everybody because everybody has different preferences. (CH2)

Well, I make it fair. One dish will be my husband’s favorite, one dish will be my daughter’s, one dish will be my son’s, you know? (CH2)

The ready availability of affordable prepared food provides a convenient way for women to meet the diverse food preferences of all family members

When women do not cook, they tend to buy take-away food, which provides an easy way to cater to the varying food preferences of individual family members:

If you cook at home, the mother decides what to eat. But if [you buy take-away food] home, we have to ask them [the children] what they want. (CL3)

Um, my kids are easy because they like delivered food. So I just ask them what they want, I go to the website, I call, order and the food is delivered to the house. (CL3)

Some women recognize the need for providing healthy foods to children

At the same time, there is recognition of the need to provide healthy foods to children, and that provision of healthy foods to children is a mother’s responsibility:

Depends on [what] the children [like], and also what is good for them. (CH1)

My child is still young, so I decide for him. For me, it is very important for him to have a balanced diet. So even it is tasteless …he has to eat it. For him, we don’t really put any salt. (CH2)

But you also must check [what the children are eating] …like, he is having too many eggs, or this week he is having too much meat. So …you have to have a checklist of your own. (CH1)

Schools, through nutrition education, can potentially influence mothers’ food decisions

Children influenced food decisions not only through their mothers’ attempts to cater to their individual food preferences but also through nutrition knowledge they gained from school:

My son is quite naggy about food because he’s studying biology …he’s already telling everybody not to drink Coke. And he’s the one who started the bean curd thing. (CL3)

My daughter wants me to stay healthy so that I can see my grandchildren. (CH1)

Not wasting food—a value

A few women took pragmatic views of how food decisions are made, and were concerned about wasting food:

They [the children] don’t decide, but we know what they want. So let’s say if I were to cook certain foods I know they won’t eat, there is no point in cooking their share also…. In the past, we used to cook a lot and end up having to throw away [left-overs]. So nowadays, I am smarter. I only cook my share, then I don’t waste the food. (CH3)

If no one wants to eat the food, then the food is wasted. Food is not cheap. (CH1)

DISCUSSION

Rapid social and economic changes in many Asian countries have been accompanied by changes in family structure. One widely studied effect of changes in family structure is the decline in fertility as women enter the workforce and delay marriage and childbirth (Call et al. 2008; Lim 2002). Less studied is the impact of these changes on the nutrition and physical growth of children as the necessary activities of feeding and food preparation are increasingly performed by individuals or units outside the family. This qualitative study is an attempt to understand how decisions relating to food purchasing, preparation, and consumption are made by Singaporean women of varying educational and ethnic backgrounds.

Women participating in the focus groups consistently held the view that today’s generation of Singaporean women cook less than their mothers did. Having to work outside the home was cited as a major reason why fewer Singaporean women cook today, compared to previous generations. According to a report by Singapore’s Ministry of Manpower (2011), the percentage of women, aged 25–54 years, in the workforce increased significantly over a decade, from 65% in 2001 to 76% in 2011 (Ministry of Manpower Singapore 2011). As observed in western societies, time is perceived as scarce for employed women with children (Jabs and Devine 2006). In our qualitative study, we identified two common strategies that Singaporean working women have adopted to perform the necessary activity of child feeding: (1) acquire food from one of the numerous cooked-food business establishments in Singapore, including at hawker centers which are conveniently found in all public-housing estates (Housing and Development Board Singapore 2011; National Environmental Agency Singapore 2012); or (2) hire a foreign domestic worker at a relatively low wage to perform the essential activity of food preparation (as well as other household activities). In a few instances, grandmothers assisted with cooking activities.

These strategies adopted by Singaporean working women can be compared to those adopted by working women in other small countries undergoing similar socioeconomic changes. An example of such a country is the Mediterranean island of Cyprus, where case studies of food provision in various types of households have recently been conducted (Minas, Jacobson, and McMullan 2013). Findings from these case studies suggest that in Cypriot families where the woman participates in the labor force, grandparents play an important role in providing home-prepared food to young children, even when the grandparents do not live in the household. This finding is consistent with the results of a survey of household food expenditure in Cyprus, which noted that food was more likely to be prepared at home when the household was managed by older women (Jacobson, Mavrikiou, and Minas 2010). Perhaps the spatial smallness of countries such as Singapore and Cyprus enables families to continue to maintain physical ties between intergenerational households. As observed in Singapore, when grandparents are not available, purchasing take-away food is common among Cypriot families with children. Additionally, like children in Singapore, children in Cyprus play an influential role in deciding what foods are purchased (Minas et al. 2013).

The role that children play in influencing food decisions is important for understanding children’s dietary habits, and has not been widely studied. In Taiwan, another Asian country where child obesity rates have been rising, it has been observed that children exert influence over meal orders and restaurant choice (Chen et al. 2013). In our focus groups, some women noted that it is less wasteful and more practical to serve children only foods that they like or would eat. From a practical standpoint, the ready accessibility of inexpensive cooked food from a variety of food stalls selling different types of food at hawker centers and food courts in Singapore makes it convenient for women to allow each child to have the food of his or her choice.

It could be argued that serving children only the foods they like may have serious implications for obesity development, even if it is seen as less wasteful of food. Children’s development of food preferences is influenced by many factors. Reducing their exposure to unhealthy foods and providing guidance to children in making healthy food choices may help nurture healthy eating habits. However, working mothers have less time to monitor their children’s exposure to unhealthy foods and to guide their children in making healthy food choices. Brown and colleagues (2010) observed that Australian children with mothers who worked part-time, watched less television and were less likely to be overweight than children with mothers who worked full-time, and suggested that mothers who work full-time may have less time or energy to supervise their children (Brown et al. 2010). Recently, Cawley and Liu (2012), using data from the American Time Use Survey, reported maternal employment is associated with less time spent on activities such as cooking, grocery shopping, and eating with children. Several studies have alluded to the importance of the family meal in promoting healthy eating behaviors in children (e.g., Gillman et al. 2000; Larson et al. 2007; Taveras et al. 2005; Woodruff et al. 2010), and in adults (Berge et al. 2012). However, it is unclear if these effects on nutritional status are attributable to the higher nutritional quality of home-prepared food or to specific characteristics of families that tend to eat dinner together. In any case, in rapidly urbanizing countries such as Cyprus, there are data to suggest that children today are less likely to eat dinner with their families (Lazarou and Kalavana 2009).

From our qualitative study findings, it appears that women with children in Singapore do not engage in food preparation on a regular basis. With the limited time they have for their families, Singaporean women with young children choose to maintain control over selected parental activities, such as taking their children to school-related activities or enrichment classes; food preparation is seen as a task that can be delegated to the retail food business or to foreign domestic workers. In the context of Singapore, while grandmothers may play a role in assisting with food preparation, the accessibility of cooked-food business establishments and the affordability of foreign domestic workers give working women convenient options for performing the essential activity of child feeding. However, both of these options present challenges in terms of efforts to improve nutrition and prevent obesity development in children. Acquisition of food from cooked-food business establishments on a regular basis implies that consumption of a healthy diet depends on the types of food sold by these establishments, and the capacity of families to make healthy food choices within this business-oriented context. Employment of a foreign domestic worker who is tasked with food preparation responsibilities implies that the worker is capable of preparing culturally and age appropriate healthy foods or receives appropriate training to do so. Because many of the domestic workers come from countries that speak a language other than the languages spoken in Singapore (i.e., English, Chinese, Malay, and to a lesser extent, Tamil), training issues can be expected. The issue of whether the domestic worker is able to prepare culturally and age appropriate healthy foods is one that is worth further investigation. Unfortunately, our study did not seek information on the ethnicity and spoken language of the domestic worker, and we are unable to examine this issue.

The extent to which households in Singapore do not regularly prepare food at home for children may be greater than in countries where inexpensive cooked food is less readily accessible. In Singapore, 82 hawker centers, spread across 26 government-subsidized housing estates where 80% of Singaporeans live (National Environmental Agency Singapore 2012), have created a unique food environment that influences the foods that Singaporean families eat and provide to their children. In 2011, there was one licensed hawker for every 345 Singaporeans (National Environmental Agency Singapore 2012). According to the National Nutrition Survey conducted in 2010, about 45% of adult Singaporeans eat at a hawker center or coffee shop5 at least 6 times a week (any meal), and nearly 30% usually eat dinner at a hawker center or coffee shop (Health Promotion Board Singapore 2013). The survey did not seek information on the frequency of eating take-away food from hawker centers or coffee shops, so these numbers underestimate the frequency of consuming food purchased from these venues. The survey also found that Chinese Singaporeans are more likely to eat at a hawker center regularly (55%) than those who are Malay (19%) or Indian (15%). These observations are consistent with our findings, which suggest that Malay and Indian women are more likely to cook than are Chinese women. Cultural differences in attitudes toward the role of women in preparing food may partially explain these ethnic differences in the prevalence of cooking among women in Singapore, despite convenient access to hawker food by all Singaporeans.

Following the experiences of women in post-industrialized western countries, women in this wealthy, industrialized nation in Asia are entering the workforce in increasing numbers (Manpower Research and Department of Statistics Singapore 2011), and are experiencing conflicting roles as they try to balance work and family responsibilities. Like working women in many western countries, working women in Singapore have reduced the time they spend in food-preparation activities (Crepinsek and Burstein 2004; Ziol-Guest, DeLeire, and Kalil 2006). However, unlike working women in countries such as the United States where fast food is most readily available and affordable, working women in Singapore have resorted to somewhat different strategies for coping with child-feeding responsibilities. They tend to provide food for their children either by buying affordable freshly prepared traditional foods from hawker centers and other food establishments, or with the help of a domestic worker who cooks. It can be argued that the social environment in Singapore supports the working woman in ways that allow her to distance herself from food preparation activities. Alternatively, it can also be argued that the working woman has created a demand for the support of child feeding activities in socioculturally acceptable ways. The effects of the strategies adopted by Singaporean working women today to provide food for their children have not been studied in relation to the development and growth of Singaporean children who experience a prevalence of obesity of about 12% (Ministry of Defense Singapore 2010). In the United States, the effects of employment outside the home on food choices in adults and children have only recently been explored (Devine et al. 2003; Devine et al. 2006). A qualitative study of the relation between work conditions and food-choice coping strategies adopted by lower income parents reported an association between long or non-standard work hours and food-choice coping strategies such as take-away food, prepared entrees, and missed meals (Devine et al. 2009). Whether this lack of involvement in food preparation by mothers—within the context of a food environment that promotes unhealthy fast and convenience foods—influences the nutritional quality of the foods children eat is an area that is ripe for investigation by child health researchers.

Throughout history, all populations have recognized the need for children to be fed and cared for. Traditionally, mothers have been the primary care-takers of young children. As increasing numbers of women work outside the home, the care of children has had to be assigned to other family members, neighbors, paid helpers, or childcare institutions. Regardless, the mother’s role in raising children is recognized, and some countries have attempted to institute work–family policies to help women balance motherhood and paid work responsibilities. Work–family policies in countries such as Sweden have been cited as models for other countries. However, while Sweden’s work–family policies have had positive effects on parents (Misra, Moller, and Budig 2007), some studies have questioned the effects of these policies on child outcomes. (Ferrarini and Duvander 2009; Tunberger and Sigle-Rushton 2011).

The few studies done on the effects of work–family policies on child outcomes have focused on the social and cognitive aspects of child well-being (Baydar and Brooks-Gunn 1991; Vandell and Ramanan 1992). The effects of work–family policies on the physical well-being and growth of children have been minimally studied. The global obesity epidemic has spurred interest in examining the effects of maternal employment on food-related behaviors in children and the role that work–family policies play in the development of child obesity. Several North American studies have reported associations between longer maternal work hours and higher child body mass index (BMI), a common indicator of adiposity (Anderson, Butcher, and Levine 2003; Chia 2008; Morrissey, Dunifon, and Kalil 2011; Phipps, Lethbridge, and Burton 2006; Ruhm 2008), but the mechanisms linking maternal employment to BMI have not been delineated. Morrissey and colleagues (2011) investigated the effects of mothers’ non-standard work hours on children’s BMI and found no association. However, the researchers noted that the association between maternal work hours and BMI is stronger among older children (12 years and older) than among younger children (Morrissey et al. 2011). We speculate that older children, being more independent, are more likely to be influenced by the external food environment, which provides increasing exposure to unhealthy processed and fast food, especially in rapidly urbanizing countries where child obesity rates are climbing (United Nations 2012). For example, in China, fast food sales more than doubled from 1999 to 2005 (Frazao, Meade, and Regmi 2008), while obesity rates increased from 20% to 30% from 1992 to 2002 (Wang et al. 2007).

The study reported here does not allow for the investigation of the contributions of the family environment and maternal employment to obesity development. However, its findings are consistent with the Theory of Triadic Influence (Flay and Petraitis 1994), which emphasizes consideration of the interactions among intrapersonal, interpersonal, and cultural–environmental determinants of health behavior when designing health promotion programs. In the context of Singapore, the availability of affordable, freshly cooked food in hawker centers provides an alternative to processed and fast food for families that choose not to prepare food at home. Can this strategy, currently used by Singaporean working women to cope with their changing roles, be tweaked so as to improve the diets of Singaporeans? Singapore’s recent implementation of the Healthier Hawker Program—which encourages food stalls to use healthier ingredients, such as whole grain rice and noodles, cooking oils that are lower in saturated fat, and salt that is lower in sodium—is a national attempt to change the food environment in Singapore (Health Promotion Board Singapore 2012). While the effectiveness of this program’s ability to address child obesity remains to be evaluated, it reminds us that the health and well-being of children and families should be considered in a holistic way as societies deal with changing demographic trends during economic transition.

Without a doubt, the current global obesity crisis is costly to society-at-large in terms of increased healthcare expenditures and decreased economic productivity (Popkin et al. 2006). The globalization of the food industry has led to the increasing availability and marketing of fast and processed food (Hawkes 2006), presenting new parental challenges for nurturing healthy eating habits in children. Future research is warranted studying the effects of maternal employment and work–family policies on food decisions impacting child growth and well-being in various sociocultural contexts, as the trend of women joining the workforce continues to spread globally. There is a need to develop and implement work–family policies that are effective not only in increasing women’s participation in the workforce but also in protecting children’s health and well-being.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National University of Singapore–Global Asia Institute Research Grant [AC-2010-1-001], and the Asia Research Institute (SF, MW).

Footnotes

Singapore generally follows the British educational system. “O” level is a standardized examination, jointly administered by the Ministry of Education, Singapore and the Cambridge University International Examinations, taken after 10 years of schooling (normally, from ages 7–16). Over 90% of students entering school (at age 7) do well enough on the “O” level examination to be admitted to post-secondary educational institutions, with the highest percentage observed among Chinese (95%) and the lowest among Malay (85%); http://www.moe.gov.sg/media/press/2011/12/performance-by-ethnic-group-in-2011.php.

“A” level is an advanced standardized examination usually taken by students who intend to enroll in a university.

As described under Methods, participants were assigned to focus groups of similar ethnicity and educational level: “C” refers to Chinese, “I” refers to Indian, and “M” refers to Malay; “H” and “L” refer to higher or lower education. The numeric suffix refers to the actual focus-group session.

A hawker center is an open-air conglomeration of many small food stalls that sell inexpensive dishes which are usually cooked only when ordered.

A coffee shop serves foods similar to those served at a hawker center food stall, but it is located in a space smaller than a hawker center.

Contributor Information

MAY C. WANG, Department of Community Health Sciences, Fielding School of Public Health, UCLA, Los Angeles, California, USA; Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health and Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, Singapore

NASHEEN NAIDOO, Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore, Singapore.

STEVE FERZACCA, Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore, Singapore; Department of Anthropology, University of Leithbridge, Leithbridge, Canada.

GEETHA REDDY, Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore, Singapore.

ROB M. VAN DAM, Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health and Department of Medicine, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University Singapore, Singapore

References

- Anderson PM, Butcher KF, Levine PB. Maternal employment and overweight children. Journal of Health Economics. 2003;22(3):477–504. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(03)00022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baydar N, Brooks-Gunn J. Effects of maternal employment and child-care arrangements on preschoolers’ cognitive and behavioral outcomes: Evidence from the Children of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27(6):932–945. [Google Scholar]

- Berge JM, MacLehose RF, Loth KA, Eisenberg ME, Fulkerson JA, Neumark-Sztainer D. Family meals. Associations with weight and eating behaviors among mothers and fathers. Appetite. 2012;58(3):1128–1135. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JE, Broom DH, Nicholson JM, Bittman M. Do working mothers raise couch potato kids? Maternal employment and children’s lifestyle behaviors and weight in early childhood. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(11):1816–1824. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Call LL, Sheffield R, Trail E, Yoshida K, Hill JE. Singapore’s falling fertility: Exploring the influence of the work–family interface. International Journal of Sociology of the Family. 2008;34(1):91–113. [Google Scholar]

- Cawley J, Liu F. Maternal employment and childhood obesity: A search for mechanisms in time use data. Economics and Human Biology. 2012;10(4):352–364. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Intelligence Agency. [accessed December 8, 2013];The world factbook 2013–2014. 2013 https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/index.html.

- Chen Y, Lehto X, Behnke C, Tang C. Investigating children’s role in family dining-out choices: A study of casual dining restaurants in Taiwan. Proceedings of the 18th Annual Graduate Student Research Conference in Hospitality and Tourism; January 3–5; Seattle, WA. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chia YF. Maternal labor supply and childhood obesity in Canada: Evidence from the NLSCY. The Canadian Journal of Economics. 2008;41(1):217–242. [Google Scholar]

- Crepinsek MK, Burstein NR. Maternal employment and children’s nutrition: Vol. II. Other nutrition-related outcomes (E-FAN-04-006-2) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2004. [accessed October 1, 2013]. http://www.ers.usda.gov/ersDownloadHandler.ashx?file=/media/1191607/efan04006-2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Deterding D. Singapore English. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Devine CM, Connors MM, Sobal J, Bisogni CA. Sandwiching it in: Spillover of work onto food choices and family roles in low- and moderate-income urban households. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56(3):617–630. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00058-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine CM, Farrell TJ, Blake CE, Jastran M, Wethington E, Bisogni CA. Work conditions and the food choice coping strategies of employed parents. Journal of Nutrition Education & Behavior. 2009;41(5):365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine CM, Jastran M, Jabs J, Wethington E, Farell TJ, Bisogni CA. “A lot of sacrifices:” Work–family spillover and the food choice coping strategies of low-wage employed parents. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63(10):2591–2603. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrarini T, Duvander AZ. Swedish family policy: Controversial reform of a success story. Stockholm, Sweden: Friedrich Ebert Foundation; 2009. [accessed October 1, 2013]. http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/stockholm/06527.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Flay BR, Petraitis J. The theory of triadic influence: A new theory of health behavior with implications for preventive interventions. In: Albrecht GS, editor. Advances in medical sociology, Vol IV: A reconsideration of models of health behavior change. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press; 1994. pp. 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Flick U. An introduction to qualitative research. 4. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Frazao E, Meade B, Regmi A. Converging patterns in global food consumption and food delivery systems. Amber Waves. 2008;6:22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Gillman MW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Frazier L, Rockett HRH, Camargo CA, Jr, Field AE, Berkey CS, et al. Family dinner and diet quality among older children and adolescents. Archives of Family Medicine. 2000;9:235–240. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkes C. Uneven dietary development: Linking the policies and processes of globalization with the nutrition transition, obesity and diet-related chronic diseases. Globalization and Health. 2006;2:4. doi: 10.1186/1744-8603-2-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Promotion Board Singapore. Healthier Hawker Food Program. Singapore: Health Promotion Board Singapore; 2012. [accessed May 24, 2013]. http://www.hpb.gov.sg/HOPPortal/article?id=2784. [Google Scholar]

- Health Promotion Board Singapore. Report of the National Nutrition Survey 2010. Singapore: Health Promotion Board Singapore; 2013. [accessed October 1, 2013]. http://www.hpb.gov.sg/HOPPortal/content/conn/HOPUCM/path/Contribution%20Folders/uploadedFiles/HPB_Online/Publications/NNS-2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Housing and Development Board Singapore. Annual Report 2010/2011. Singapore: Housing and Development Board Singapore; 2011. [accessed October 1, 2013]. http://www10.hdb.gov.sg/ebook/ar2011/keystats.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Jabs J, Devine CM. Time scarcity and food choices: An overview. Appetite. 2006;47(2):196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson D, Mavrikiou PM, Minas C. Household size, income and expenditure on food: The case of Cyprus. The Journal of Socio-Economics. 2010;39(2):319–328. [Google Scholar]

- Khoo KC. The shaping of childcare and preschool education in Singapore: From separatism to collaboration. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy. 2010;4:23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Story M. Family meals during adolescence are associated with higher diet quality and healthful meal patterns during young adulthood. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2007;107:1502–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarou C, Kalavana T. Urbanization influences dietary habits of Cypriot children: The CYKIDS study. International Journal of Public Health. 2009;54(2):69–77. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-8054-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SM, Alvarez G, Palen JJ. Fertility decline and pronatalist policy in Singapore. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1991;17:65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Lim LL. Completing the fertility transition. Population Bulletin of the United Nations. New York, NY: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division; 2002. [accessed October 1, 2013]. Female labor force participation. http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/completingfertility/RevisedLIMpaper.PDF(2002) [Google Scholar]

- Manpower Research and Department of Statistics Singapore. Occasional paper: Singaporeans in the workforce. Singapore: Government of Singapore Department of Statistics; 2011. [accessed October 1, 2013]. http://www.mom.gov.sg/Publications/mrsd_singaporeans_in_the_workforce.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Minas C, Jacobson DS, McMullan C. Welfare regime and inter-household food provision: The case of Cyprus. Journal of European Social Policy. 2013;23:300–314. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Defense Singapore. Obesity in children. Government of Singapore Ministry of Defense; 2010. [accessed October 1, 2013]. http://www.mindef.gov.sg/imindef/mindef_websites/topics/elifestyle/articles/miscellaneous/obesity_in_children.html. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Manpower Singapore. Singapore Workforce. Government of Singapore Ministry of Manpower; 2011. [accessed October 1, 2013]. www.mom.gov.sg/Publications/mrsd_singapore_workforce_2011.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Misra J, Moller S, Budig MJ. Work–family policies and poverty for partnered and single women in Europe and North America. Gender and Society. 2007;21:804–827. [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey TW, Dunifon RE, Kalil A. Maternal employment, work schedules, and children’s body mass index. Child Development. 2011;82(1):66–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01541.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Environmental Agency Singapore. Hawkers department. Government of Singapore National Environmental Agency; 2012. [accessed October 1, 2013]. http://app2.nea.gov.sg/hawkers_dept.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Phipps SA, Lethbridge L, Burton P. Long-run consequences of parental paid work hours for child overweight status in Canada. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62(4):977–986. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popkin BM, Kim S, Rusev ER, Du S, Zizza C. Measuring the full economic costs of diet, physical activity and obesity-related chronic diseases. Obesity Reviews. 2006;7(3):271–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2006.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyle JL. Women, the family, and economic restructuring: The Singapore model? Review of Social Economics. 2001;55:215–223. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhm CJ. Maternal employment and adolescent development. Labor Economics. 2008;15(5):958–983. doi: 10.1016/j.labeco.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobal J, Bisogni CA. Constructing food choice decisions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;38:S37–S46. doi: 10.1007/s12160-009-9124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun SHL. Reproducing citizens: Gender, employment, and work–family balance policies in Singapore. Journal of Workplace Rights. 2009;14:351–374. [Google Scholar]

- Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Berkey CS, Rockett HR, Field AE, Frazier AL, Colditz GA, Gillman MW. Family dinner and adolescent overweight. Obesity Research. 2005;13:900–906. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teo Y. Shaping the Singapore family: Producing the state and society. Economy and Society. 2010;39:337–359. [Google Scholar]

- Tunberger P, Sigle-Rushton W. Continuity and change in Swedish family policy reforms. Journal of European Social Policy. 2011;21:225–237. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World urbanization prospects: The 2011 revision. New York, NY: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division; 2012. [accessed October 1, 2013]. http://esa.un.org/unup/ [Google Scholar]

- Vandell DL, Ramanan J. Effects of early and recent maternal employment on children from low-income families. Child Development. 1992;63:938–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Mi J, Shan XY, Wang QJ, Ge KY. Is China facing an obesity epidemic and the consequences? The trends in obesity and chronic disease in China. International Journal of Obesity. 2007;31(1):177–188. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb S. Pushing for babies: Singapore fights fertility decline. [accessed October 1, 2013];Singapore window. 2006 http://www.singapore-window.org/sw06/060426re.htm.

- Westley SB, Choe MK, Rutherford RD. Very low fertility in Asia: Is there a problem? Can it be solved? Asia Pacific issues: Analysis from the East West Center. 2010:94. [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff SJ, Hanning RM, McGoldrick K, Brown KS. Healthy eating index-C is positively associated with family dinner frequency among students in grades 6–8 from Southern Ontario, Canada. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2010;64:454–460. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong G. Singapore advocacy groups campaign “days off” for maids. [accessed October 1, 2013];The Irrawaddy. 2008 http://www2.irrawaddy.org/print_article.php?art_id=11709.

- Yeoh BSA, Huang S, Gonzalez J., III Migrant female domestic workers: Debating the economic, social and political impacts in Singapore. International Migration Review. 1999;33(1):114–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziol-Guest K, DeLeire T, Kalil A. The allocation of food expenditure in married and single-parent families. Journal of Consumer Affairs. 2006;40:347–371. [Google Scholar]