Abstract

Background

Hospitalizations for heart failure are associated with a high post-discharge risk for mortality. Identification of modifiable predictors of post-discharge mortality during hospitalization may improve outcome. Sleep disordered breathing (SDB) is the most common co-morbidity in heart failure patients.

Design, setting, and participants

Prospective cohort study of patients hospitalized with acute heart failure (AHF) in a single academic heart hospital. Between January 2007 and December 2010, all patients hospitalized with AHF who have left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤ 45% and were not already diagnosed with SDB were the target population.

Main outcomes and measures

Patients underwent in-hospital attended polygraphy testing for SDB and were followed for a median of 3 years post-discharge. Mortality was recorded using national and state vital statistics databases.

Results

During the study period, 1117 hospitalized AHF patients underwent successful sleep testing. Three hundred and forty-four patients (31%) had central sleep apnoea (CSA), 525(47%) patients had obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA), and 248 had no or minimal SDB (nmSDB). Of those, 1096 patients survived to discharge and were included in the mortality analysis. Central sleep apnoea was independently associated with mortality. The multivariable hazard ratio (HR) for time to death for CSA vs. nmSDB was 1.61 (95% CI: 1.1, 2.4, P = 0.02). Obstructive sleep apnoea was also independently associated with mortality with a multivariable HR vs. nmSDB of 1.53 (CI: 1.1, 2.2, P = 0.02). The Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for the following covariates: LVEF, age, BMI, sex, race, creatinine, diabetes, type of cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, discharge systolic blood pressure <110, hypertension, discharge medications, initial length of stay, admission sodium, haemoglobin, and BUN.

Conclusions

This is the largest study to date to evaluate the effect of SDB on post-discharge mortality in patients with AHF. Newly diagnosed CSA and OSA during AHF hospitalization are independently associated with post-discharge mortality.

Keywords: Heart failure, Sleep disordered breathing, Sleep apnoea, Post-discharge mortality

See page 1428 for the editorial comment on this article (doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehv084)

Introduction

Heart failure (HF), a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the developed world, continues to increase in incidence.1,2 The mortality rates of HF remain largely unchanged despite several advances in the management of cardiovascular disease.3,4 Hospitalizations for acute heart failure (AHF) account for a significant portion of the human and economic burden of HF.3

Attention focused in recent years on determining predictors of HF mortality and readmissions in order to trigger targeted interventions for high-risk patients. Several predictors have been identified, most of which are non-modifiable demographic, physiological, or functional factors. Interventions that are likely to improve outcomes such as guideline medical therapy, disease management programs, and early post-discharge follow-up are already part of the current standard of care. Identification of new modifiable risk factors may provide an opportunity to decrease mortality.5–10

Sleep disordered breathing (SDB) is the most common comorbidity in patients with HF.11 Sleep disordered breathing is associated with neurohumoural and clinical perturbations that can decompensate stable HF.12,13 The negative impact of SDB might be most pronounced during AHF hospitalizations and in the immediate post-discharge period. We recently found that newly diagnosed SDB during hospitalization for AHF is a novel independent predictor of HF readmissions.14 From this background, we hypothesized that SDB would be an independent predictor of post-discharge mortality as well.

Methods

Study population and participants

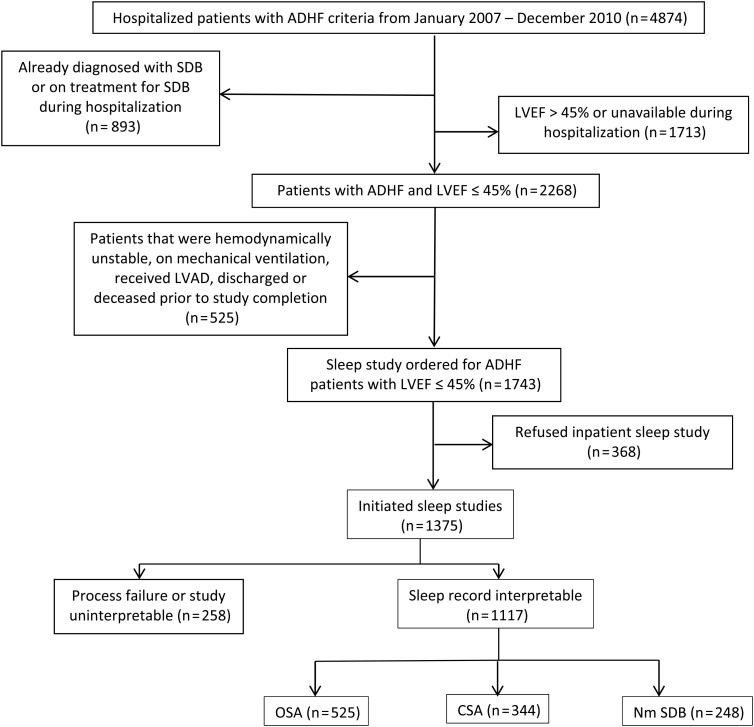

All patients who were hospitalized at the Ohio State University (OSU) Ross Heart Hospital with an admission diagnosis of heart failure between January 2007 and December 2010 were targeted for enrolment. Only HF patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF ≤ 45%) (HFrEF) were included in this study. Acute heart failure was defined according to the standard clinical guidelines as having a chief complaint of dyspnoea or fatigue, and at least one sign and one symptom of elevated left ventricular pressure. Sleep study orders are part of the electronic admission order set for heart failure at the OSU Ross Heart Hospital and are performed regardless of any screening or risk factors for SDB. Patients who were already diagnosed with SDB or were on treatment did not receive the in-hospital sleep study. Figure 1 details the disposition of AHF patients in the study and describes the screening and testing process.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the screening process and disposition of participants. AHF, acute heart failure; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; in-hospital mortality on patients with completed sleep studies was 21 patients (6 CSA, 12 OSA, 3 negatives); 1096 survived the hospitalization.

Sleep studies and group definitions

The in-hospital sleep studies were attended cardiorespiratory studies (Stardust II, Respironics, Inc.) that measure respiratory effort, oxygen saturation, nasal flow, and pulse rate. Cardiorespiratory polygraphy is widely used for the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) and central sleep apnoea (CSA) in patients with HF.11,15,16 We have reported on our validation of in-hospital testing in AHF patients and its high positive predictive value (>90%) for the persistence of OSA17 and CSA14 against polysomnography done in the stable outpatient state. Trained night shift nurses who noted the patients' visual sleep and wakefulness and any interruptions to sleep attended the in-hospital sleep studies. The nurse also ensured the integrity of the recording by checking and reapplying leads as needed. Patients were considered for the sleep study starting on the second night of hospitalization. The sleep studies were not done on patients who are unstable, moderately hypoxic (oxygen saturation <87% on room air), haemodynamically unstable, or unable to sleep in <30° position. Attempts were made on subsequent nights during the hospitalization to perform the sleep studies when these patients became more stable. Studies were interrupted or terminated if the patient became unstable. Segments of the study that included simultaneously more than one missing signal were subtracted from the recording time. An intact effort signal was required for any segment to be interpretable. Respiratory event scoring and classification of OSA and CSA were according to standard clinical criteria18 and used oxygen desaturation cut-off of 3% for hypopneas (no arousal criterion is used). An AHI cut-off of 15 events/hour was selected for the in-hospital study to mitigate against the expected increase in respiratory control instability and oxygen desaturation during the AHF episode. Patients with AHI < 15 were classified as having minimal or no SDB (nmSDB) and served as the control group for the SDB patients. Two technicians and one Sleep Physician who were blinded to the clinical status of the patient performed the scoring and interpretation.

Outcomes

A registry of all patients who underwent the sleep study during hospitalization was established in 2007 to evaluate the effect of SDB on post-discharge outcomes. The primary outcome was post-discharge all-cause mortality. Demographic information on all hospitalized AHF patients who underwent a successful recording was stored in a database by a research coordinator without knowledge of the SDB status. The OSU-Information Warehouse (OSU-IW), which interfaces with the electronic medical record and national and state vital statistics provided mortality, readmissions, and dates of last encounter on all patient in the registry. The data were entered separately by a coordinator blinded to the SDB status. Another coordinator added demographic and SDB status by searching the OSU Sleep Heart Program server for the reports of the sleep studies. The demographic and outcome data were combined by the OSU Center for Biostatistics into one database. A close out date was predetermined for July 31, 2013 for the whole database. The close out date was used to establish censored follow-up time for all patients who remained alive according to the databases. Patients who had no post-discharge outpatient or readmission data in the OSU-IW after discharge were <10% (23 (7%) with CSA, 39 (7%) with OSA, and 26 (10%) with nmSDB. These patients were still included in the primary mortality analysis, since it depended only on the vital statistics.

The study protocol was approved by the OSU Institutional Review Board [2007H0043 and 2007H0055]. This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Follow-up procedure and classification of patients by treatment status

In-hospital sleep testing was instituted by the OSU Sleep Heart Program as a clinical screening program in 2005. Patients and physicians were aware that the purpose of the in-hospital sleep studies was screening and that follow-up was to be arranged in the outpatient setting if the studies were positive for SDB. All patients who tested positive for SDB were informed of their diagnosis prior to discharge and were provided follow-up appointments at the OSU Sleep Center prior to their discharge. Patients were also sent reminder letters in the first year post-discharge. Some patients elected to follow-up locally and others did not follow-up. In order to explore the relation between treatment status and changes in the risk of post-discharge mortality, we classified patients as treated and untreated in the first year post discharge. Patients who were confirmed by download or Sleep physician report to have been using the treatment device >4 h/night between 6 and 12 months post-discharge were classified as ‘treated’. Patients who were classified as ‘untreated’ were patients who rejected device therapy; were still in the process of obtaining and starting device therapy in the 6–12 months post-discharge; or may have been on device therapy but the adherence was not verifiable by review of the records.

Statistical design and analysis

We described the baseline characteristics of the study population using frequencies with percentages for categorical variables and means with standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. We planned a primary hypothesis test that compared post-discharge all-cause mortality of screen identified CSA patients with patients who screened negative (nmSDB). We also planned to compare screen identified OSA patients with the screen negatives. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Inc., Cary NC, USA, 2009).

The comparisons were made within a Cox proportional hazards model with time to death as the outcome. The model adjusted for a set of covariates that were found previously to distinguish severity or to predict negative outcomes in HF patients.7,19 The covariates used in the model are listed in Table 1. Note that we used all variables with no selection process to ensure that the reported SDB effects could not be explained by any of these measures of risk or severity. To adjust for testing two hypotheses (CSA and OSA vs. nmSDB), we used Holms procedure,20 and so strongly controlled the overall type 1 error rate for the two tests at α = 0.05. Double-sided testing was used to generate P-values. The sample size was determined to have at least 80% power to detect a 60–70% increase in mortality for the CSA and OSA hypothesis tests. Sixty-three per cent of the patients were included in a previously published analysis of effect of CSA on 6 months readmissions only; but mortality analysis was not done prior to this analysis; and mortality data were not yet collected.14 In a sensitivity analysis, we applied the same Cox proportional hazards model using time to last follow-up (outpatient visit or readmission date) as the censoring time, rather than the study close out date.

Table 1.

Comparison of characteristics among the three groups of patients with acute heart failure

| Patient characteristic | Mean (SD) or n (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| CSA (n = 344) | OSA (n = 525) | nmSDB (n = 248) | |

| Age | 60.3 (14.7)# | 60.3 (13.0)^ | 54.6 (15.2)#^ |

| Sex (male) | 281 (82%)*# | 381 (73%)*^ | 139 (56%)#^ |

| Race | |||

| White | 255 (75%)* | 451 (86%)* | 200 (82%) |

| Black | 72 (21%) | 63 (12%) | 36 (15%) |

| Other | 13 (4%) | 10 (2%) | 7 (3%) |

| Cardiomyopathy | |||

| Ischaemic | 229 (67%)# | 342 (65%)^ | 126 (51%)#^ |

| Dilated or non-ischaemic | 77 (22%) | 134 (26%) | 86 (35%) |

| Others | 38 (11%) | 49 (9%) | 36 (15%) |

| LVEF (%) | 23.1 (10.4)*# | 26.3 (10.5)*^ | 29.5 (10.4)#^ |

| BMI (kg/cm2) | 29.4 (7.7)* | 31.7 (7.7)*^ | 29.0 (6.8)^ |

| Initial length of stay (days) | 9.5 (12.5)# | 9.0 (11.4)^ | 7.2 (8.0)#^ |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 161 (53%)# | 268 (51%)^ | 94 (38%)#^ |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.44 (0.80)# | 1.39 (0.80)^ | 1.20 (0.67)#^ |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 25.7 (16.4)# | 26.1 (17.0)^ | 20.7 (15.1)#^ |

| BNPa (pg/L) | |||

| <50 | 9 (4%)*# | 20 (6%)*^ | 14 (11%)#^ |

| 50–99 | 7 (3%) | 21 (6%) | 14 (11%) |

| 100–499 | 75 (31%) | 130 (38%) | 40 (32%) |

| ≥500 | 152 (63%) | 175 (51%) | 57 (46%) |

| Coronary artery disease (%) | 232 (68%)# | 365 (70%)^ | 140 (56%)#^ |

| Diabetes (%) | 123 (36%)* | 255 (49%)*^ | 78 (31%)^ |

| Hypertension (%) | 164 (48%) | 284 (54%) | 119 (48%) |

| Discharge of ACEI or ARB (%) | 247 (72%) | 355 (69%) | 176 (72%) |

| Discharged on β-blockers (%) | 305 (89%) | 456 (88%) | 214 (87%) |

| Discharged on diuretics (%) | 206 (60%)# | 318 (62%)^ | 125 (51%)#^ |

| Discharge SBP < 110 mmHg | 177 (53%) | 249 (48%) | 133 (55%) |

| Admission Na (mEq/L) | 136.8 (3.4) | 136.6 (3.0) | 137.0 (2.7) |

| Admission haemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.2 (1.9) | 12.2 (2.4) | 12.2 (1.9) |

LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; BMI, body mass index; BNP, B-type natriuretic peptide; ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

an = 714.

*P<0.05 between CSA and OSA groups.

#P < 0.05 between CSA and nmSDB groups.

^P < 0.05 between OSA and nmSDB groups.

To explore whether treatment for SDB modifies the mortality rate, only patients with at least 6 months survival post-discharge were included. This ensured that patients in this exploratory analysis had the opportunity to receive treatment. We fit a Cox proportional hazards model for mortality, which included SDB group, treatment status, and the interaction between SDB group and treatment status, along with all of the covariates from the primary model. Parameter contrasts were constructed to obtain the hazard ratios (HRs) vs. the nmSDB group.

Results

Patient characteristics

During the study period, interpretable studies were done on 1117 consecutive hospitalized patients with AHF and LVEF ≤ 45%. Of these patients, 344 had CSA, 525 had OSA, and 248 had nmSDB. In-hospital death occurred in 21 patients: 6 CSA (2%), 12 OSA (2%), and 3 (1%) patients with nmSDB. These patients were excluded from the post-discharge mortality analysis reported below.

Patients' characteristics were similar to other large registries and clinical trials of hospitalized HF patients.9 Group characteristics are listed in Table 1. Most patients had decompensation of previously recognized HFrEF, and a minority (n = 36) had de novo AHF. The most common causes of decompensation were arrhythmia, ischaemic events, and pneumonia. There were expected differences among the groups in baseline characteristics including cardiac function, weight, and age that were consistent with previous reports of patients with HF and SDB.11,17 As noted previously, all characteristics listed in Table 1 were included as covariates in the proportional hazards model reported below. The median follow-up time was 35.8 months (IQR 22.3–36.0 months). Table 2 includes the parameters of the in-hospital sleep study on all patients.

Table 2.

Comparisons of in-hospital sleep study parameters among the three groups

| In-hospital sleep study parameter | Mean (SD) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| CSA (n = 344) | OSA (n = 525) | nmSDB (n = 248) | |

| AHI (events/h) | 47 (16.3)#* | 36 (16)^* | 9.5 (4.3)#^ |

| CAI (apnoea/h) | 26 (14.6)#* | 3 (4.3)^* | 0.65 (1.5)#^ |

| OAI (apnoea/h) | 11.2 (8)#* | 19 (14)^* | 3.3 (2.8)#^ |

| HYI (hypopnea/h) | 10 (10)# | 14 (0.7)^ | 5.6 (3.7)#^ |

| 3% desaturation index (events/hour) | 41 (20)#* | 29.6 (20)^ | 8 (5.2)#^ |

| Mean oxygen saturation (%) | 92 (8)# | 91 (11)^ | 95.6 (3)#^ |

| Time <95% saturation (min) | 111.6 (106)#* | 136 (118)^* | 92(111)#^ |

| Time <90% saturation (min) | 30 (40)# | 33 (61)^ | 11 (42)#^ |

| Time <85% saturation (min) | 9 (27)# | 8 (26)^ | 4 (11)#^ |

| Recording time (min) | 329 (102.9) | 318 (105) | 339 (99.8) |

*P < 0.05 between CSA and OSA groups.

#P < 0.05 between CSA and nmSDB groups.

^P < 0.05 between OSA and nmSDB groups.

Effect of sleep disordered breathing on post-discharge morality

Effect of central sleep apnoea on post-discharge mortality

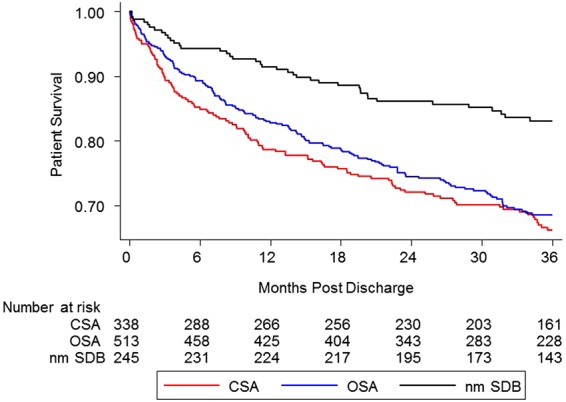

Newly diagnosed CSA proved to be a risk factor for post-discharge mortality. Figure 2 is the Kaplan–Meier survival curve comparing SDB groups to nmSDB. The univariable HR for time to death over 36 months was 2.17 (95% CI, 1.5, 3.1), P < 0.001. For the primary hypothesis test, the multivariable HR was 1.61 (95% CI: 1.1, 2.4) P = 0.02 (meeting the Holms first significance cut-off of 0.025) Table 3 details the Cox proportional hazards models for time to death over the 3-year follow-up for the three groups. Using the sensitivity analysis with the date of last encounter instead of time to death increased the multivariable HR slightly (HR = 1.77). The effect of CSA on mortality at 1, 2, and 3 years is reported in Table 4.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier post-discharge survival plot of acute heart failure patients by sleep disordered breathing status. OSA, obstructive sleep apnoea. CSA, central sleep apnoea. nmSDB, no or minimal sleep disordered breathing.

Table 3.

Cox proportional hazards models for time to death, 36 month follow-up

| Model | Hazard ratio (95% confidence interval), P-value |

|

|---|---|---|

| CSA vs. nmSDB | OSA vs. nmSDB | |

| Univariate | 2.17 (1.5, 3.1) P < 0.001 |

2.00 (1.4, 2.9) P < 0.001 |

| Multivariablea | 1.61 (1.1, 2.4) P = 0.02 |

1.53 (1.1, 2.2) P = 0.02 |

aModel included LVEF, age, BMI, sex, race, creatinine, diabetes, type of cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, discharge SBP < 110, hypertension, discharge ACEI or ARB, discharge β-blocker, initial length of stay, admission Na, admission haemoglobin, and BUN.

Table 4.

Kaplan–Meier cumulative mortality estimates at one-year intervals post-discharge

| Months post-discharge | CSA | OSA | nmSDB |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15 (4%a; 3%, 7%) | 17 (3%; 2%, 5%) | 3 (1%; 0%, 4%) |

| 12 | 72 (21%; 17%, 26%) | 88 (17%; 14%, 21%) | 21 (9%; 6%, 13%) |

| 24 | 94 (28%; 23%, 33%) | 130 (25%; 22%, 30%) | 34 (14%; 10%, 19%) |

| 36 | 110 (34%; 29%, 39%) | 153 (31%; 27%, 36%) | 40 (17%; 13%, 22%) |

aPercentages from the Kaplan–Meier curve with 95% confidence intervals.

Effect of obstructive sleep apnoea on post-discharge mortality

Similar to CSA, OSA was an independent risk factor for post-discharge mortality. The multivariable HR for OSA vs. nmSDB was 1.53 (CI, 1.1, 2.2), P = 0.02, also significant (Table 3). The effect on mortality was substantial in all of the 3 years of follow-up as noted in Table 4 and Figure 2.

Over the 3-year follow-up, the unadjusted mortality rates were: CSA 110 (34%), OSA: 153 (32%), and nm-SDB 40 (17%). Because the HRs were similar for CSA and OSA, we obtained a combined group HR, the SDB univariable HR for time to death over 36 months was 2.09 (1.5, 2.9) P < 0.001, and the multivariable ratio was 1.57 (1.1, 2.2) P = 0.01.

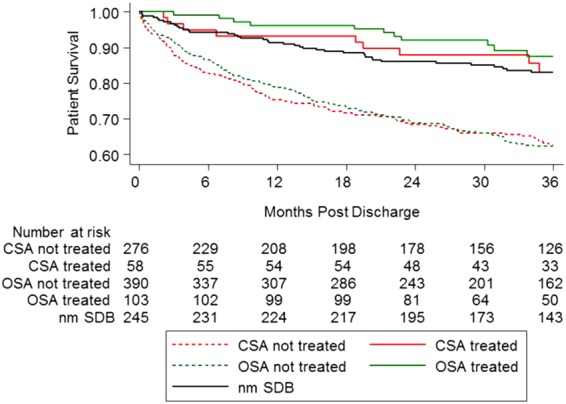

Exploration of a modification of the mortality effect with sleep disordered breathing treatment

In the first year post-discharge, 58 CSA patients and 103 OSA patients were verified to have been on positive airway pressure therapy with adequate adherence as defined above. Two hundred and six patients with CSA and 337 patients with OSA were not confirmed to be on therapy by the end of the first year post-discharge and were classified as untreated. Table 5 lists the comparisons in HRs between the groups by treatment status and the reference nmSDB group. Figure 3 is a survival plot of patients by treatment status. Note that the SDB mortality effect for those in the untreated group is more pronounced than those reported above for the overall SDB groups and is absent in the subjects who elected treatment. This could be due to confounding as discussed below.

Table 5.

Comparisons of the hazard ratios for mortality over 36 months among subgroups by treatment status

| Comparison | Hazard ratio* | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| CSA treated vs. nmSDB | 0.79 (0.37, 1.7) | 0.54 |

| OSA treated vs. nmSDB | 0.58 (0.29, 1.1) | 0.12 |

| CSA not treated vs. nmSDB | 1.9 (1.3, 2.9) | 0.001 |

| OSA not treated vs. nmSDB | 1.8 (1.3, 2.7) | 0.001 |

*Model included LVEF, age, BMI, sex, race, creatinine, diabetes, type of cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, chronic kidney disease, discharge SBP < 110, hypertension, discharge ACEI or ARB, discharge β-blocker, initial length of stay, admission Na, admission haemoglobin, and BUN.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier post-discharge survival plot of acute heart failure patients by treatment status. The plot includes acute heart failure patients who survived 6 months post-discharge and had their treatment status verified.

Other predictors of post-discharge mortality

The covariates used in the proportional hazards modelling for the SDB effect are listed in Table 6. These covariates are similar to previously reported predictors of mortality post-discharge in large registries of HF admissions.7,19,21 We explored the SDB and gender interaction and the BMI and SDB interaction effects on mortality and both were not significant. We also explored whether using a continuous measurement for systolic blood pressure (instead of the dichotomy) changed the results, and it did not.

Table 6.

Cox proportional hazards models for time to death, 36 month follow-up of all covariables

| Variable | HR (95% CI)* | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| CSA vs. nmSDB | 1.61 (1.1, 2.4) | 0.02 |

| OSA vs. nmSDB | 1.54 (1.1, 2.2) | 0.02 |

| LVEF | 0.77 (0.6, 1.0) | 0.06 |

| AGE | 1.46 (1.09, 1.94) | 0.01 |

| BMI | 0.68 (0.51, 0.90) | 0.01 |

| Female vs. male | 0.98 (0.7, 1.3) | 0.86 |

| Black vs. white | 1.61 (1.2, 2.2) | 0.004 |

| Other vs. white | 0.63 (0.2, 1.7) | 0.37 |

| Creatinine | 0.88 (0.65, 1.2) | 0.38 |

| CKD | 1.51 (1.1, 2.0) | 0.01 |

| Diabetes | 1.16 (0.9, 1.5) | 0.26 |

| Cardiomyopathy, Ischaemic vs. other | 1.20 (0.7, 2.0) | 0.47 |

| Cardiomyopathy, dilated vs. other | 0.90 (0.5, 1.5) | 0.70 |

| CAD | 1.25 (0.8, 1.90) | 0.27 |

| Initial SBP < 110 | 1.54 (1.2, 2.0) | <0.001 |

| Initial LOS | 0.86 (0.7, 1.1) | 0.24 |

| Discharged on β-blocker | 0.84 (0.6, 1.2) | 0.39 |

| Discharged on ACEI/ARB | 0.8 (0.6, 1.0) | 0.09 |

| Admission Na | 0.60 (0.5, 0.8) | <0.001 |

| Admission haemoglobin | 0.62 (0.4, 0.9) | 0.004 |

| BUN | 1.40 (1.2, 1.6) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0.91 (0.7, 1.2) | 0.51 |

*Hazard ratios are for a 2-SD increase for these continuously measured risk factors (2 SD = LVEF 21%, age 29 years, BMI 15 kg/m2, initial length of stay 22 days, creatinine 1.6 mg/dL, admission Na 4.1 mg/dL, admission haemoglobin 4.7 g/dL, BUN 16.7); the remaining covariates were dichotomized or trichotomized (race, cardiomyopathy).

Discussion

This prospective, single-centre cohort study is the first evaluation of the effect of SDB on post-discharge mortality in patients with AHF and reduced LVEF. Furthermore, this report is the largest prospective evaluation of the effect of SDB on mortality in HF patients. Newly diagnosed CSA or OSA on a surveillance in-hospital sleep-testing program are both independently associated with post-discharge mortality in patients with systolic HF who are hospitalized for AHF. Based on the multivariable models, these increased risks cannot be explained by severity, demographics and any other baseline patient's characteristics listed in Table 1. Interestingly, exploratory analysis based on treatment status suggests the association between SDB and mortality is not persistent in the treated group. Compared with the other predictors of post-discharge mortality and poor outcome in HF, SDB is potentially treatable and may provide an opportunity to impact the outcome of HF hospitalizations.

Important studies have reported on independent relationship between SDB and mortality in untreated patients with chronic stable HF.22–24 This study was designed as a prospective cohort in all hospitalized patients with AHF avoiding the potentially biasing effect of referral to the sleep facility. The primary analysis of this study included all patients regardless of their treatment status and only explored the difference in the mortality experience between patients who accepted and pursed treatment and the remainder of the patients. The cause of death in the majority of patients was congestive HF, which can be related to dysrhythmic, or neurohumoural complications of SDB as recently shown.12 The population of this study is similar in characteristics and event rate to populations of large registries and trials in hospitalized HF patients, making the findings immediately generalizable to clinical practice.21

The device (Stardust II) used in this study for the in-hospital identification and classifications of SDB is a limitation. The device uses one effort belt resulting in a relatively large number of recording failures (Figure 1). We mitigated this problem by direct observation by nurses who replaced any displaced belts or sensors. In addition, the nurses documented visual sleep resulting in improved detection of events. We also were able to repeat studies on subsequent nights of hospitalization in patients with recording failure. Another consideration in testing during the decompensation episode is that the occurrence or severity of SDB may be increased by increased cardiac filling pressure.25 We have validated this technique, approach, and interpretation against outpatient polysmnography previously. Despite some decrease in AHI on the outpatient polysmnography, the positive predictive value for SDB was excellent.14,17

The use of cardiorespiratory polygraphy instead of polysomnography for the detection and classification of SDB during the hospitalization is critical for providing a practical and generalizable method of case finding in this high-risk population and setting.

The effect of treatment of either CSA or OSA on survival in HF patients remains unknown. Exploratory analysis in this study suggests that treated patients had survival similar to patients with nmSDB. Although it appears as if treatment eliminates the increased mortality due to SDB, confounding effects associated with the type of patients who seek SDB treatment could explain this result. Note also that those classified as untreated could have received SDB treatment after the first year, which means the untreated HRs could be conservatively biased. This observation supports the need for adequately powered trials evaluating treatment effects on post-discharge outcomes. Pilot studies with adaptive servo ventilators demonstrate a beneficial effect on outcomes of chronic HF.26 Powered trials addressing the effect of treatment of SDB on composite outcomes of patients with stable HF are currently underway.27

SDB remains largely undiagnosed in the majority of patients with HF.28 The independent mortality effect of SDB along with the previously demonstrated effect on readmissions14 provide justification for routine screening for SDB during AHF hospitalizations.

Funding

This research was supported by in part by a grant from National Institute of Health (R21 HL092480) R.N.K., D.J., W.T.A., K.P. The research was also supported by the National Center for Research Resources (ULRR025755) R.N.K., D.J., K.P. The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of NCRR or NIH.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.From AM, Leibson CL, Bursi F, Redfield MM, Weston SA, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ, Roger VL. Diabetes in heart failure: prevalence and impact on outcome in the population. Am J Med 2006;119:591–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker WH, Mullooly JP, Getchell W. Changing incidence and survival for heart failure in a well-defined older population, 1970–1974 and 1990–1994. Circulation 2006;113:799–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams RJ, Brown TM, Carnethon M, Dai S, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Ford E, Furie K, Gillespie C, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern S, Ho PM, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lackland D, Lisabeth L, Marelli A, McDermott MM, Meigs J, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino M, Nichol G, Roger VL, Rosamond W, Sacco R, Sorlie P, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wong ND, Wylie-Rosett J. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2010 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2010;121:e46–e215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bueno H, Ross JS, Wang Y, Chen J, Vidan MT, Normand SL, Curtis JP, Drye EE, Lichtman JH, Keenan PS, Kosiborod M, Krumholz HM. Trends in length of stay and short-term outcomes among Medicare patients hospitalized for heart failure, 1993–2006. JAMA 2010;303:2141–2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muzzarelli S, Leibundgut G, Maeder MT, Rickli H, Handschin R, Gutmann M, Jeker U, Buser P, Pfisterer M, Brunner-La Rocca HP. Predictors of early readmission or death in elderly patients with heart failure. Am Heart J 2010;160:308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, Hammill BG, Heidenreich PA, Yancy CW, Peterson ED, Curtis LH. Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA 2010;303:1716–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Stough WG, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH, O'Connor CM, Pieper K, Sun JL, Yancy CW, Young JB. Factors identified as precipitating hospital admissions for heart failure and clinical outcomes: findings from OPTIMIZE-HF. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:847–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fonarow GC. The relationship between body mass index and mortality in patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure. Am Heart J 2007;154:e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Stough WG, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH, O'Connor CM, Pieper K, Sun JL, Yancy C, Young JB. Association between performance measures and clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized with heart failure. JAMA 2007;297:61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fonarow GC, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Gattis Stough W, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH, O'Connor CM, Pieper K, Sun JL, Yancy CW, Young JB. Influence of a performance-improvement initiative on quality of care for patients hospitalized with heart failure: results of the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients With Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF). Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1493–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oldenburg O, Lamp B, Faber L, Teschler H, Horstkotte D, Topfer V. Sleep-disordered breathing in patients with symptomatic heart failure: a contemporary study of prevalence in and characteristics of 700 patients. Eur J Heart Fail 2007;9:251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bitter T, Westerheide N, Prinz C, Hossain MS, Vogt J, Langer C, Horstkotte D, Oldenburg O. Cheyne-Stokes respiration and obstructive sleep apnoea are independent risk factors for malignant ventricular arrhythmias requiring appropriate cardioverter-defibrillator therapies in patients with congestive heart failure. Eur Heart J 2011;32:61–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naughton MT, Benard DC, Liu PP, Rutherford R, Rankin F, Bradley TD. Effects of nasal CPAP on sympathetic activity in patients with heart failure and central sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1995;152:473–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khayat R, Abraham W, Patt B, Brinkman V, Wannemacher J, Porter K, Jarjoura D. Central sleep apnea is a predictor of cardiac readmission in hospitalized patients with systolic heart failure. J Card Fail 2012;18:534–540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paulino A, Damy T, Margarit L, Stoica M, Deswarte G, Khouri L, Vermes E, Meizels A, Hittinger L, d'Ortho MP. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in a 316-patient French cohort of stable congestive heart failure. Arch Cardiovasc Dis 2009;102:169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quintana-Gallego E, Villa-Gil M, Carmona-Bernal C, Botebol-Benhamou G, Martinez-Martinez A, Sanchez-Armengol A, Polo-Padillo J, Capote F. Home respiratory polygraphy for diagnosis of sleep-disordered breathing in heart failure. Eur Respir J 2004;24:443–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khayat R, Jarjoura D, Patt B, Yamokoski T, Abraham WT. In-hospital testing for sleep-disordered breathing in hospitalized patients with decompensated heart failure: report of prevalence and patient characteristics. J Card Fail 2009;15:739–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medicine AAoS. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Connor CM, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Clare R, Gattis Stough W, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH, Yancy CW, Young JB, Fonarow GC. Predictors of mortality after discharge in patients hospitalized with heart failure: an analysis from the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF). Am Heart J 2008;156:662–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure Scandinavian. J Stat 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abraham WT, Fonarow GC, Albert NM, Stough WG, Gheorghiade M, Greenberg BH, O'Connor CM, Sun JL, Yancy CW, Young JB. Predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients hospitalized for heart failure: insights from the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF). J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:347–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Javaheri S, Shukla R, Zeigler H, Wexler L. Central sleep apnea, right ventricular dysfunction, and low diastolic blood pressure are predictors of mortality in systolic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:2028–2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jilek C, Krenn M, Sebah D, Obermeier R, Braune A, Kehl V, Schroll S, Montalvan S, Riegger GA, Pfeifer M, Arzt M. Prognostic impact of sleep disordered breathing and its treatment in heart failure: an observational study. Eur J Heart Fail 2011;13:68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Damy T, Margarit L, Noroc A, Bodez D, Guendouz S, Boyer L, Drouot X, Lamine A, Paulino A, Rappeneau S, Stoica MH, Dubois-Rande JL, Adnot S, Hittinger L, d'Ortho MP. Prognostic impact of sleep-disordered breathing and its treatment with nocturnal ventilation for chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2012;14:1009–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solin P, Bergin P, Richardson M, Kaye DM, Walters EH, Naughton MT. Influence of pulmonary capillary wedge pressure on central apnea in heart failure. Circulation 1999;99:1574–1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oldenburg O, Bitter T, Wellmann B, Fischbach T, Efken C, Schmidt A, Horstkotte D. Trilevel adaptive servoventilation for the treatment of central and mixed sleep apnea in chronic heart failure patients. Sleep Med 2013;14:422–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cowie MR, Woehrle H, Wegscheider K, Angermann C, d'Ortho MP, Erdmann E, Levy P, Simonds A, Somers VK, Zannad F, Teschler H. Rationale and design of the SERVE-HF study: treatment of sleep-disordered breathing with predominant central sleep apnoea with adaptive servo-ventilation in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2013;15:937–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Javaheri S, Caref EB, Chen E, Tong KB, Abraham WT. Sleep apnea testing and outcomes in a large cohort of medicare beneficiaries with newly diagnosed heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:539–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]