Abstract

Sexually explicit media (SEM) is viewed by many men who have sex with men (MSM) and is widely available via the Internet. Though research has investigated the link between SEM and sexual risk behaviour, little has been published about preferences for characteristics of SEM. In an Internet-based cross-sectional study, 1390 adult MSM completed an online survey about their preferences for nine characteristics of SEM and ranked them in order of importance. Respondents preferred free, Internet-based, anonymous SEM portraying behaviours they would do. Cost and looks were the most important characteristics of SEM to participants, while condom use and sexual behaviours themselves were least important. Results suggest that while participants may have preferences for specific behaviours and condom use, these are not the most salient characteristics of SEM to consumers when choosing.

Keywords: sexually explicit media, pornography, men who have sex with men, condom use

Introduction

Sexually explicit media (SEM) is defined as ‘any kind of material aimed at creating or enhancing sexual feeling or thoughts in the viewer, and containing explicit exposure and/or depictions of the genitals as well as clear and explicit sexual acts (e.g., vaginal intercourse, anal intercourse, oral sex, masturbation, bondage, etc.)’ (Hald & Malamuth, 2008). SEM is viewed by many men who have sex with men (MSM) and is widely accessible (Morrison, Morrison, & Bradley, 2007). The global SEM industry now generates an estimated $100 billion annually, of which $13 billion comes from the United States (Carroll et al., 2008). In the early 2000s, the US market share of SEM portraying sex between men was estimated to be 10–25% of all SEM (Rich, 2001; Thomas, 2000). By 2007, that estimate rose to 33–50% of SEM (Morrison et al., 2007). In the 2000s, however, bareback SEM production became more common, reportedly driven by consumer demand (Holt, 2008).

Currently, there is a growing body of research on SEM focusing specifically on its relation to sexual risk behaviour (Eaton, Cain, Pope, Garcia, & Cherry, 2011; Hald et al., in press; Peter & Valkenberg, 2011; Rosser et al., 2013; Sinković, Štulhofer, & Božić, 2012). In a study investigating the relationship between SEM consumption and HIV risk among MSM, researchers found that preferences for condom use in SEM reflected participants’ preferences for condom use in real life, both with insertive and receptive anal intercourse (Rosser et al., 2013). People who preferred SEM without condoms had higher numbers of unprotected anal intercourse (UAI) partners and people who preferred SEM with condoms had fewer UAI partners (Rosser et al., 2013). Prior research into specific characteristics of SEM has focused largely on portrayed behaviours (e.g., condom use, types of sexual acts) but has not investigated which other characteristics are relevant to consumers, such as cost and medium (Grudzen et al., 2009; Silvera, Stein, Hagerty, & Marmor, 2009).

MSM continue to be at disproportionately high risk for HIV infection (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010). While new biomedical approaches to HIV prevention are being introduced, condoms remain the best known and least expensive method for HIV prevention, as well as being highly effective (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2013; Hall et al., 2008 ). In spite of this, barebacking remains a highly prevalent behaviour among MSM (Berg, 2009; Blackwell, 2008; Parsons & Bimbi, 2007). Estimates of prevalence vary geographically and range from 10% to 65% of adult US MSM reporting bareback sexual behaviour in cross-sectional, community-based studies (Huebner, Proescholdbell, & Nemeroff, 2006; Mansergh et al., 2002). In Internet-based studies, between 39.2% and 83.9% of MSM report bareback sex (Berg, 2008; Halkitis & Parsons, 2003). Many MSM report learning about sexuality from SEM, which suggests that SEM could potentially influence the condom use behaviours of consumers (Kubicek, Beyer, Weiss, Iverson, & Kipke, 2010; Kubicek, Carpineto, McDavitt, Weiss, & Kipke, 2010; Morrison, 2004; Mustanski, Lyons, & Garcia, 2011). The potential for SEM to increase condom use among MSM and to be a part of sex education merits consideration.

SEM could act as a medium in at least three ways; through sexually explicit public service announcements (PSAs) targeted towards MSM (e.g., on online sex-seeking sites), through sexually explicit educational materials tailored for MSM, or by promoting safer sex within SEM (e.g., through policies or self-governance by the SEM industry). There are several precedents of sex education being delivered via SEM (DCFUK!T, n.d. LaRue, 2010; Swedish Educational Broadcasting Company, 2012), and through the 1990s, the gay SEM industry imposed a self-governance requiring all anal sex to be depicted using condoms.

Though legislation requiring condom use in the production of SEM exists in some jurisdictions (e.g., the city of Los Angeles, California’s ‘Measure B’), these policies focus primarily on protecting the health of performers and not the preferences of SEM consumers (Los Angeles Times, 2012; Safer Sex in the Adult Film Industry Act, 2012). A common argument from people against regulations is that there is a strong consumer demand for SEM without condoms (del Barco, 2013; Los Angeles Times, 2012). There is little published empirical research to support or refute this claim, however. For those in the SEM industry, knowing the preferences of their audience is important. Finally, it is important for researchers studying SEM as it relates to fields such as sexual health and HIV prevention to know which characteristics are most salient.

In this paper, first, we describe the development of a new scale to measure preferences and the relative importance of nine characteristics of SEM. Second, we describe the preferences for characteristics of SEM among a diverse sample of Internet-using MSM noting differences across key demographic characteristics (i.e., age, race and HIV status).

Methods

Participants

Internet-using MSM completed online surveys about their use of SEM and sexual behaviour as part of a reliability study (N = 325) and main study (N = 1390). Many measures used in this survey, including the measures discussed in this manuscript, were developed by our team and were not previously tested for reliability. Thus, we conducted a 7-day test–retest reliability analysis before recruiting a larger sample for our main analysis. Participants in the reliability study were recruited online between January and February 2011, using banner advertisements on gay-oriented websites affiliated with an advertising agency specialising in gay consumers (see Appendix 1). A total of 448,472 impressions were displayed during this period and banners had a click-through-rate (CTR) of 0.31%. Participants in the main study were recruited using the same method between May and August 2011. For that campaign, banner advertisements were displayed on gay-oriented websites for a total of 7,939,758 impressions, with a CTR of 0.16%.

For both studies, banner advertisements directed interested persons to a webpage hosted on a dedicated university server with appropriate encryption to ensure data security. Persons were screened for eligibility, which were being male, having had sex with at least one man over the past 5 years, being 18 years of age or older, and living in the United States (including its territories). Participants in the reliability study were then given the same survey 7 days later to enable the study team to assess test–retest reliability. Participants in the main study answered survey items once. During analysis, we excluded participants who gave suspicious responses that were determined fraudulent (N = 64). To identify fraudulent responses, we used a deduplication protocol that included the following criteria: duplicate IP addresses, inconsistent responses to racial or ethnic identity, zip code and age, confirmed by asking these items multiple times in our survey (Konstan, Rosser, Ross, Stanton, & Edwards, 2006). In addition, we excluded participants with impossible numbers of sexual partners or nonsensical data patterns in responses to sexual behaviour questions. Next, in order to determine the potential impact of missing data, we conducted our analyses both with the full sample using pairwise deletion and including only completers using list-wise deletion and observed no statistically significant differences between estimates. Next, we used two-sample t-tests to measure differences between participants who completed the survey and participants who partially completed based on age (t = −0.84, p = .40), income (t = 0.45, p = .65), number of lifetime male sexual partners (t = −1.45, p = .15) and number of male sexual partners in the past 90 days (t = −1.58, p = .11) and found none of these to be statistically significant at p = .05, though non-completers reported higher mean numbers of both lifetime and 90-day male sexual partners (144.2 and 4.6, respectively) than completers (95.8 and 3.7, respectively). Thus, in order to maximise statistical power, we used a final analytic sample of 1390, with 287 partially complete surveys, handling missing data with pairwise deletion. Demographic characteristics for the final samples obtained are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the samples in the reliability and main surveys.

| Reliability survey

|

Main survey

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| N | 325 | 1390 | ||

| Race or ethnicity | ||||

| White or Caucasian | 288 | 88.34 | 604 | 41.46 |

| Black or African American | 13 | 3.99 | 467 | 11.46 |

| Latino or Hispanic, any race | 32 | 7.98 | 441 | 30.27 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 13 | 3.99 | 108 | 7.41 |

| American Indian | 9 | 2.76 | 25 | 1.72 |

| Other/Multi | 4 | 1.23 | 112 | 7.69 |

| Age | ||||

| 18–25 | 102 | 31.38 | 544 | 37.34 |

| 26–35 | 105 | 32.31 | 456 | 31.30 |

| 36–45 | 57 | 17.48 | 217 | 14.89 |

| Over 45 | 45 | 13.85 | 178 | 12.22 |

| 55+ | 16 | 4.92 | 62 | 4.26 |

| HIV status | ||||

| HIV-negative | 270 | 82.82 | 1119 | 76.85 |

| HIV-positive | 20 | 6.13 | 133 | 20.40 |

| HIV-unsure | 36 | 11.04 | 204 | 14.01 |

Measures

In both studies, participants were asked about their preferences regarding broad characteristics of SEM as well as the importance of those characteristics (see Appendix 2). For the reliability study, participants were asked to choose between two anchors using a five-point semantic differential for each of eight characteristics: cost (free vs. for pay), production (amateur vs. professional), condom (safer sex vs. bareback), medium (online vs. offline), site type (member vs. anonymous), taboo content (things they would do vs. things they would not do), body type of performers (specific looks vs. a range of looks) and genre (vanilla vs. kinky). Participants were then asked to rate the same characteristics in terms of importance using a five-point scale, ranging (‘very important’ to ‘not at all important’).

For the main study, two changes were made to the measures. First, an additional characteristic, types of behaviour (a mix of everything vs. specific acts), was added to the list to yield a total of nine SEM characteristics. Second, the survey was modified to ask relative importance for each characteristic by ranking, rather than absolute importance, using a rating item. This was done because participants in the reliability study rated many characteristics equally important (which provided insufficient variance on which to compare items) and these items had low test–retest reliability (see Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

| Characteristic | Weighted Kappa | Std. error | Z | Pr > Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | 0.70 | 0.063 | 11.01 | <0.0001 |

| Production | 0.66 | 0.0644 | 10.26 | <0.0001 |

| Condoms | 0.70 | 0.0635 | 11.08 | <0.0001 |

| Medium | 0.54 | 0.0645 | 8.35 | <0.0001 |

| Site type | 0.63 | 0.0640 | 9.83 | <0.0001 |

| Taboo | 0.55 | 0.0641 | 8.61 | <0.0001 |

| Actors’ looks | 0.61 | 0.0644 | 9.47 | <0.0001 |

| Genre | 0.73 | 0.0636 | 11.51 | <0.0001 |

Notes:

7-day test–retest reliability.

Ratings presented in a survey as cost (free vs. for pay), production (amateur vs. professional), condoms (safer sex vs. bareback), medium (online vs. offline), site type (member vs. anonymous), taboo (things you would do vs. things you would not do), Actors’ looks (generic looks vs. specific looks) and genre (vanilla vs. kink).

Table 3.

Test–retest reliability of importance,† N = 325.

| Characteristic | Weighted Kappa | Std. error | Z | Pr > Z |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | 0.53 | 0.0645 | 8.17 | <0.0001 |

| Production | 0.37 | 0.0641 | 5.82 | <0.0001 |

| Condoms | 0.45 | 0.0644 | 6.98 | <0.0001 |

| Medium | 0.36 | 0.0645 | 5.53 | <0.0001 |

| Site type | 0.44 | 0.0645 | 6.87 | <0.0001 |

| Taboo | 0.22 | 0.0628 | 3.55 | 0.0002 |

| Actors’ looks | 0.33 | 0.0625 | 5.23 | <0.0001 |

| Genre | 0.27 | 0.0628 | 4.34 | <0.0001 |

Note:

7-day test–retest reliability.

Analysis

Test–retest reliability was assessed using weighted Kappa statistics with quadratic weights (Cohen, 1968). To assess preferences, we compared measures of central tendency. For ranked items, mean, mode, median rankings, quartiles and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were used to sort the order of importance. The orders of items using median and mean ranks were very similar. However, because skewness existed in the distributions of several of these characteristics and mean ranks were very similar for many of the items, quartiles of ranks and IQRs were used as our final method to sort these items. First, items were ordered based upon 25th percentile, then in order of 50th percentile where there were ties in the 25th percentile responses and finally, then ordered based upon 75th percentile where ties existed in 50th percentile ranks.

For characteristics posed as semantic differentials, two-tailed t-tests were used to determine whether means reflected a consistent trend in preference across our sample. Means were tested against a null value indicating no preference (i.e., for a semantic differential on a scale from 1 to 5, the null value was 3). In the main survey, t-tests were statistically significant for nearly every characteristic (8 of 9), even when the differences between the mean value and null values were quite small, suggesting high power with little meaning. Where median and mode values equalled the null value while t-tests were statistically significant, these results were categorised as ‘possible artefacts of sample size’. To assess variability in responses across demographics, Pearson chi-square (χ2) tests of homogeneity were calculated to assess differences in responses to these items (both preferences between items and importance of items) across race, age and HIV status, indicated under Tables 4 and 5. Finally, in order to identify the magnitude of these associations while accounting for the large sample size, Cramer’s V was calculated, presented in Tables 6 and 7 (Cohen, 1988).

Table 4.

Preferences in main survey,a N = 1365.

| Characteristic | Preference | M (SD) | t | 95% Confidence interval | Mode | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CostA | Free | 1.35 (0.76) | −79.0** | 1.31, 1.39 | 1 | 1 |

| ProductionP | Neutral | 2.89 (1.04) | −3.90* | 2.83, 2.84 | 3 | 3 |

| Condom useHP | Marginal | 3.24 (1.22) | 6.70** | 3.16, 3.29 | 3 | 3 |

| MediumA | Online | 3.75 (1.19) | 23.00** | 3.68, 3.81 | 5 | 4 |

| Site typeA | Anonymous | 2.18 (1.14) | −26.89** | 2.11, 2.23 | 1 | 2 |

| TabooR | Would | 2.40 (1.13) | −19.19** | 2.35, 2.47 | 3 | 2 |

| Actors’ looks P | Specific | 3.43 (0.94) | 16.76** | 3.38, 3.47 | 3 | 3 |

| BehaviourRAP | Mix | 2.84 (1.16) | −5.07** | 2.78, 2.90 | 3 | 3 |

| GenreRHP | Neutral | 3.01 (1.03) | 0.39 | 2.96, 3.07 | 3 | 3 |

Notes:

Indicates p-value from χ2 test of homogeneity across race <.05.

Indicates p-value from χ2 test of homogeneity across age <.05.

Indicates p-value from χ2 test of homogeneity across HIV status <.05.

Indicates possible artefacts of sample size (see Methods section).

Rating items are presented in a survey as cost (free vs. for pay), production (amateur vs. professional), condom use (safer sex vs. bareback), medium (online vs. offline), site type (member vs. anonymous), taboo (things you would do vs. things you would not do), actors’ looks (generic looks vs. specific looks), behaviour (A mix of everything vs. specific acts) and genre (vanilla vs. kink).

Indicates p-value from t-test <.001.

Indicates p-value from t-test <.0001.

Table 5.

Importance in main survey, unordered N = 1310.

| Characteristic | M (SD) | 95% Confidence interval | Median rank | Mode rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | 2.30 (2.32) | 2.18, 2.43 | 1 | 1 |

| Production | 5.1 (2.37) | 4.97, 5.23 | 5 | 2 |

| Condom useR | 5.83 (2.6) | 5.69, 5.98 | 6 | 9 |

| Medium | 5.76 (2.59) | 5.63, 5.91 | 6 | 9 |

| Site type | 5.24 (2.39) | 5.11, 5.38 | 5 | 3 |

| TabooA | 6.18 (2.09) | 6.07, 6.30 | 6 | 9 |

| LooksA | 4.02 (2.13) | 3.91, 4.14 | 4 | 3 |

| Behaviour | 5.05 (2.01) | 4.94, 5.16 | 5 | 4 |

| Genre | 5.86 (2.21) | 5.74, 5.98 | 6 | 8 |

Notes:

Indicates p-value from χ2 test of homogeneity across race <.05.

Indicates p-value from χ2 test of homogeneity across age <.05.

Table 6.

Chi-squared and Cramer’s V between demographic characteristics and preference items N = 1310.

| Race | Age | HIV status | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| Characteristic | χ2 | V | p-Value | χ2 | V | p-Value | χ2 | V | p-Value |

| Cost | 30.61 | .07 | .06 | 30.02 | .07 | .02 | 8.09 | .05 | .43 |

| Production | 27.67 | .12 | .07 | 16.70 | .06 | .41 | 10.49 | .06 | .23 |

| Condom use | 24.47 | .07 | .22 | 21.00 | .06 | .18 | 48.23 | .13 | <.01 |

| Medium | 20.54 | .06 | .43 | 37.69 | .08 | <.01 | 8.06 | .05 | .43 |

| Site type | 24.01 | .07 | .24 | 39.13 | .08 | .08 | 11.03 | .06 | .20 |

| Taboo | 35.84 | .08 | .02 | 20.53 | .06 | .20 | 4.61 | .04 | .80 |

| Looks | 21.96 | .06 | .34 | 21.04 | .06 | .18 | 5.13 | .04 | .74 |

| Behaviour | 42.63 | .09 | <.01 | 29.41 | .07 | .02 | 734 | .05 | .50 |

| Genre | 34.66 | .08 | .02 | 20.18 | .06 | .21 | 36.08 | .12 | <.01 |

Table 7.

Chi-squared and Cramer’s V between demographic characteristics and rankings N = 1310.

| Race

|

Age

|

HIV status

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | χ2 | V | p-Value | χ2 | V | p-Value | χ2 | V | p-Value |

| Cost | 36.75 | .07 | .62 | 28.74 | .07 | .63 | 8.09 | .05 | .43 |

| Production | 34.45 | .07 | .72 | 33.38 | .08 | .40 | 10.49 | .06 | .23 |

| Condom use | 59.44 | .10 | .03 | 22.44 | .06 | .90 | 48.23 | .13 | <.01 |

| Medium | 34.03 | .07 | .74 | 19.87 | .07 | .95 | 8.06 | .05 | .43 |

| Site type | 32.46 | .07 | .80 | 25.65 | .07 | .08 | 11.03 | .06 | .20 |

| Taboo | 41.01 | .08 | .43 | 20.53 | .06 | .20 | 4.61 | .04 | .80 |

| Looks | 42.09 | .08 | .38 | 21.04 | .06 | .18 | 5.13 | .04 | .74 |

| Behaviour | 41.94 | .08 | .39 | 29.41 | .07 | .02 | 7.34 | .05 | .50 |

| Genre | 53.01 | .09 | .08 | 20.18 | .06 | .21 | 36.08 | .12 | <.01 |

Results

Preferred characteristics of SEM

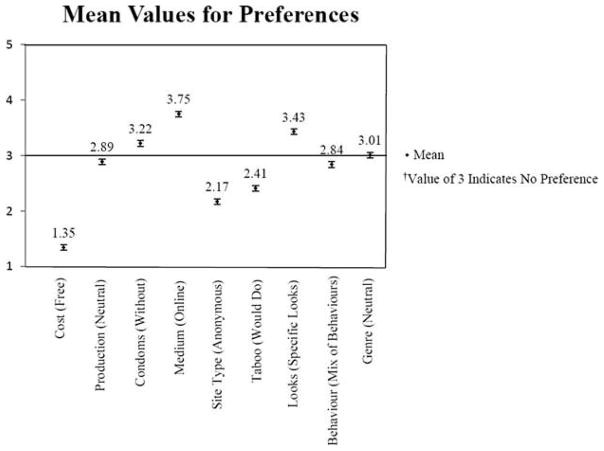

Participants had the strongest preference for free SEM. Participants also preferred SEM that was available online, did not require a membership for viewing, depicted acts they would engage in and featured actors who had a specific looks and portrayed a mixture of behaviours (Table 4). Though t-tests were statistically significant for nearly every characteristic, median and mode values suggested that participants had strong preferences for only a few of these items (see Figure 1). For example, though the mean suggested a preference for SEM without condoms (M = 3.22, t = 6.7, p < .001), the median and mode responses were both equalled 3. Based upon the magnitude of difference in means from null value, the characteristics that respondents of our main survey had the strongest preferences for were cost, medium, taboo and type of site.

Figure 1.

Mean preferences for all items.

Preferences in cost varied across age (χ2(16, N = 1366) = 30.02, p = .018), though this association was weak (V = .07). Younger men (aged 18 and 24) reported the strongest preference for free SEM (M = 1.26, SD = 0.69), while older men (aged 55 and above) had the weakest preference for free SEM (M = 1.42, SD = 0.82); however, no age group preferred ‘for pay’ SEM. Preferences for condom use varied across HIV status, χ2(16, N = 1369) = 48.23, p < .001, and this association was moderately strong (V = .13). HIV-positive participants preferred SEM portraying sex without condoms (M = 3.85, SD = 1.19), while HIV-negative and HIV-unsure participants did not have a strong preference as a group (M = 3.14, SD = 1.21 among HIV-negative MSM, M = 3.27, SD = 1.26 among HIV-unsure). Thirty-five per cent of our main survey’s sample had no preference for or against condom use in SEM and only 25% ranked condom use among their top three most important characteristics of SEM (not displayed in tables).

Preferences for SEM had statistically significant variability across age, χ2(16, N = 1366) = 37.69, p = .002, though this association was weak (V = .07). No age group preferred offline SEM, however, the preference for online SEM was strongest among MSM aged 18–24 (M = 3.85, SD= 1.19), while MSM over 55 had the weakest preference between online and offline SEM (M = 3.46, SD = 1.22). With respect to online SEM, preferences between anonymous and membership sites showed statistically significant variability across age groups, χ2(16, N = 1366) = 39.13, p = .001, which was weak after accounting for sample size (V = .07). No age group preferred membership sites (range 2.07–2.56), however, the preference for anonymous sites was strongest among participants between the ages of 18 and 24 (M = 2.07, SD = 1.11).

Across all races and ethnicities, respondents slightly preferred SEM portraying acts they would engage in to acts they would not do (range of means for Taboo was 2.38–2.5). The differences in preferences were statistically significant χ2(16, N = 1366) = 35.84, p = .016, though it was weak (V = .08). All groups preferred to view SEM portraying acts they would engage in, with white MSM having the strongest preference (M = 2.38, SD = 1.09) and black MSM having the most neutral mean response (M = 2.55, SD = 1.09). Finally, differences in preferences for ‘genre’ of SEM were present between men of different HIV status, χ2(16, N = 1366) = 36.08, p < .001, which was a moderately strong relationship (V = .12). HIV-positive MSM had a mean response indicating a slight preference for ‘kinky’ SEM (M = 3.46, SD = 1.01) while HIV-negative and HIV-unsure participants had mean responses suggesting little to no group-level preferences between ‘kinky’ and ‘vanilla’ SEM (M = 2.95, SD = 1.01 and M = 3.07, SD = 1.07, respectively).

Importance of SEM characteristics

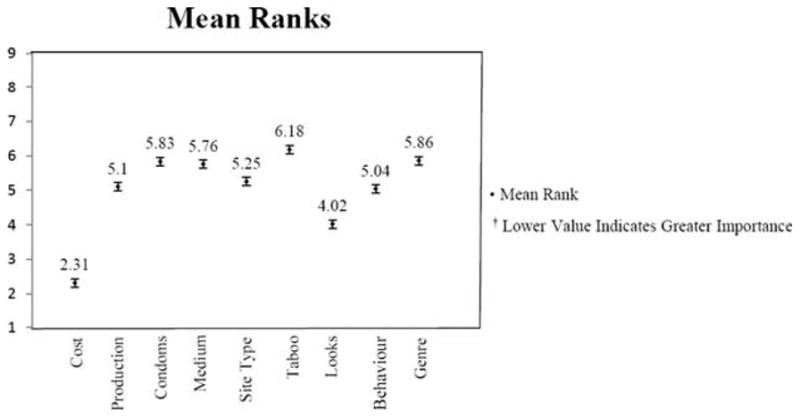

Cost was the most important characteristic to respondents, ranked as most important by 64% of our sample (Table 8). Its median and mode values (both equalled 1) also reflected this finding, along with having the smallest IQR. Aside from cost (M = 2.31, SD = 2.32), mean ranks remained close together (eight items with mean rankings between 4.02 and 6.30; see Figure 2). The importance of cost did not show significant variability across demographics.

Table 8.

Ranked order of items, sorted by quantiles, N = 1310.

| Characteristic | 25th percentile | 50th percentile | 75th percentile | Interquartile range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Looks | 2 | 4 | 5 | 3 |

| Production | 3 | 5 | 7 | 4 |

| Site type | 3 | 5 | 7 | 4 |

| Medium | 3 | 6 | 8 | 5 |

| Behaviour | 4 | 5 | 7 | 3 |

| Genre | 4 | 6 | 8 | 4 |

| Condom use | 4 | 6 | 8 | 4 |

| Taboo | 5 | 6 | 8 | 3 |

Figure 2.

Mean rankings for all items.

The importance of condom use showed some variability across racial categories (Table 7); on average, condom use had the greatest importance among black MSM (M = 5.21, SD = 2.53) and was least important to other/multiracial MSM (M = 6.48, SD = 2.37). Though condom use was ranked as most important by black MSM, as a group they had no preference between viewing SEM with and without condoms t(152) = 0.53, p = .59 (not shown in tables). Among age groups, men over 55 ranked the category ‘taboo’ with greatest importance (M = 5.92, SD = 2.31) while men between the ages of 18 and 24 had the lowest mean rank (M = 6.23, SD = 2.12). On average, looks of performers was most important to men between the ages of 25 and 34 (M = 3.85, SD = 2.10), and least important to men over 55 (M = 4.71, SD = 2.27).

Discussion

Our study found that cost is the most important characteristic of SEM to this sample of Internet-using MSM. The cost and popularity of SEM have made it an industry with profits on par with Hollywood (Escoffier, 2003). An Internet search of online vendors of SEM in DVD format from major studios found many titles costing between $20 and $60 per DVD; given the popularity of SEM suggested by the revenue it generates, it would follow that consumers want to find SEM at the lowest cost (Channel 1 Releasing, 2012; Duroy, 2013; Titan Media, 2013). Free SEM is more commonly available online, so the high importance of cost offers one explanation of the preference for Internet-based SEM we found among our samples. This also suggests the possibility that consumer behaviour in SEM is similar to other markets (e.g., other media, clothing, books).

Several other features of Internet-based SEM may give it advantages to offline SEM in the eyes of consumers: new SEM can be obtained from a computer without travelling to a store or waiting for delivery, it is more convenient and accessible, there is a greater range of titles and latest releases and finally there are no physical materials (e.g., magazines, DVDs) to store, which could be advantageous to consumers concerned about privacy. In addition, this may be related to other trends in consumption of other media; the popularity of streaming technology for other media as such and movies and music has changed these industries, this may be the same for SEM. There are several plausible reasons why our sample preferred anonymous sites. First, many membership sites are for pay and many anonymous sites are free. Since cost was the most important characteristic of SEM to our sample and free SEM was preferred, this could lead to a preference for anonymous sites as well. Additionally, concerns for confidentiality, due to a desire to maintain anonymity and/or to protect the privacy of personal financial information could explain this preference.

A preference for free Internet-based SEM may present challenges for the wider MSM health movement. Producers of this type of SEM may not be regulated and it may also be self-generated, which could make engagement challenging for health providers. The popularity of free Internet-based SEM also implies a need for change in approach by the MSM health movement in health interventions within the SEM paradigm. Consequently, the MSM health movement needs to be agile in engaging this market.

Though many items varied statistically significantly across demographics, few of these differences seemed substantial; others may have been artefacts of sample size. For example, the difference across racial groups for preferences in the category ‘taboo’ was statistically significant, but the difference between the two most extreme means did not suggest a difference in preference that would lead to different choices in content between groups; it is possible that this may have been due to the highly different numbers of participants within each racial group. Similarly, after accounting for sample size, results suggested that most associations between these items and demographic characteristics were weak. Thus, these findings should be validated in further study, preferably with greater balance of sample sizes between demographic groups.

The general preference in taboo was for acts that one ‘would do’. Despite this preference, taboo was ranked as unimportant. A model of SEM consumption (the sexual risk behaviour model; Wilkerson et al., 2012) can offer a potential explanation. According to this model, sexual intentions change when SEM portraying new behaviours is found arousing by participants and sexual behaviours change when participants both find these new behaviours pleasurable in life and find available sex partners. In this situation, there would be little incentive for someone to continue viewing SEM portraying acts neither arousing nor pleasurable. Additionally, once a person reaches a point where they rarely see SEM portraying novel acts, the question of taboo could become less important, and viewing novel SEM less possible.

Perhaps the most surprising finding was that condom use was ranked so often as unimportant (mode rank = 9). Because such a strong emphasis is placed on condom use in health education strategies targeted towards MSM and there has been substantial cultural discourse about condom-less SEM from both health educators and the SEM industry, we expected condom use to have greater importance. Considering the variety of other characteristics included in this survey, it is possible that condom use is simply less salient than others such as cost, looks of actors and medium. Further exploration of this finding is a necessary next step for our research. In particular, examining previously established links between preferences for portrayal of condom use and condom use behaviours in life with studies of different populations and with designs which can assess temporality can explore the implications of this finding for the SEM industry and HIV prevention (Rosser et al., 2013).

These data came from a cross-sectional survey; having only surveyed these individuals once, inferences about long-term patterns of behaviour cannot be made. Additionally, our use of an Internet-based sample may have led to information bias; the strong preference for online SEM among our respondents may be due to a stronger preference for Internet-based media in general, as a part of being Internet-using MSM. In addition, recruiting a convenience sample from the Internet limits the external validity of our results and their generalisability to other populations, especially non-Internet users and MSM who do not access gay-themed websites. In addition, men who go online specifically to use SEM or engage in riskier sexual behaviours may have been less likely to participate. Though the difference was not statistically significant, non-completers of the main survey had higher 90-day and lifetime male sexual partners.

We did not collect test–retest reliability data for the rankings of items that we used as our final format in the main study. Thus, our results rely on the untested assumption that rankings were a more reliable and better way to measure importance than the rating method we used initially. Alternative methods, such as the ‘Q’ method of sorting, were not used, but may have been (more) appropriate to assess preferences and importance of these characteristics of SEM. However, other studies have found rankings to be superior to ratings at finding distinctions between measures of importance (Alwin & Krosnick, 1985). Our data, then, identify relative importance, but we do not have data from the main survey on the absolute importance of each item. Finally, all results were group-level inferences using measures of central tendency, caution should be taken in translating these group-level response patterns into individual-level preferences.

These findings set up the potential for several future studies. First, researchers can examine these characteristics in other populations (e.g., heterosexuals, women, non-Internet using MSM) and determine if and how preferences and importance differ. Market researchers in the SEM industry could determine the impact of preferences and importance on SEM purchasing and viewing behaviour. Finally, researchers in HIV prevention can examine the relationship between preferences and importance of characteristics of SEM and sexual risk behaviours with more rigorous study designs (e.g., longitudinal studies).

We presented information about the preferences of this sample of Internet-using MSM. SEM is a highly eclectic medium with a variety of content, and though preferences vary greatly between individuals, cost was consistently the most important characteristic to our sample overall, followed by looks of the actors, production and non-membership site. Based on these results, if one could describe the characteristics of SEM that would maximise satisfaction on those characteristics most important, it would be a free video available on the Internet, portraying actors with specific looks on a site that can be accessed without membership. After meeting those criteria, whether or not the sexual acts portrayed by performers are risky is a distal consideration. Condom use was unimportant to our sample overall and a sizable proportion had no preference for or against portrayal of condom use are in SEM. While preferences vary between individuals, these results suggest that risky sex is generally not one of the first characteristics considered when choosing SEM. For health educators and others using SEM for HIV prevention, it is imperative to consider aspects beyond behaviours to reach a target population.

Acknowledgments

All research was carried out with the approval of the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board, study number 0906S68801.

Funding

Understanding the Effects of Web-based Media on Virtual Populations was funded by the National Institutes of Mental Health Center for Medical Health Research on AIDS [grant number 5R01MH087231].

Appendix 1. Reliability study

| Site | Clickthrough rate | Impressions |

|---|---|---|

| AGB-Style | 2.27 | 17 |

| Another Guy Blog | 0.44 | 2613 |

| Ask Gay Men | 25 | 2 |

| BEARNATION.us – Social Network | 2.08 | 376 |

| BIZ | 11.11 | 9 |

| Back2Stonewall.com | 2.67 | 75 |

| Ben and Dave’s Six Pack | 10 | 14 |

| BigJock | 0.89 | 48 |

| Black Gay Gossip | 0.27 | 724 |

| Break the Illusion | 0.46 | 631 |

| Bryanboy: Le Superstar Fabuleux | 0.34 | 130 |

| Charmants | 0.44 | 229 |

| ChicagoPride | 0.64 | 157 |

| Connexion | 1.61 | 15,653 |

| Cruising Gays | 1.32 | 1257 |

| Dlist | 0.6 | 2671 |

| Dailymotion | 0.31 | 456 |

| Deep Dish | 0.74 | 203 |

| FindFred | 0.67 | 10,306 |

| Gay Authors | 1.12 | 89 |

| GayCities | 0.72 | 3849 |

| Grab Magazine | 16.67 | 6 |

| Hit Dan Back | 0.13 | 427 |

| Homorazzi Media | 0.2 | 3612 |

| Homotron | 2.7 | 37 |

| Homotrophy Gay Blog | 0.21 | 3000 |

| JoeMyGod | 2.89 | 3447 |

| JustGuys | 0.37 | 9224 |

| LA Rag MAg | 0.22 | 1635 |

| Labidos | 1.32 | 227 |

| MANofAUSTIN | 1 | 180 |

| Manjam | 0.6 | 7589 |

| Mark’s List | 0.22 | 273 |

| OHBoyMagazine | 9.09 | 3 |

| OkCupid – Gay | 0.06 | 1678 |

| On Top Magazine | 0.13 | 2258 |

| OneGoodLove – Gay | 0.75 | 12 |

| Out In America Cities Network | 0.8 | 3381 |

| OutLoudBlogs | 1.57 | 366 |

| Outsports | 0.68 | 7564 |

| Pink Kryptonite | 1.54 | 195 |

| Planet Homo | 0.88 | 46 |

| PopWired | 0.75 | 103 |

| Project RunGay – Tom and Lorenzo | 0.27 | 28,732 |

| Qnotes | 9.09 | 22 |

| Queerty | 0.45 | 7339 |

| ROD 2.0 | 0.85 | 485 |

| RealJock | 0.3 | 28,232 |

| SportsFags | 0.16 | 1259 |

| Tabloid Heat | 0.07 | 7 |

| Tabloid Prodigy | 0.07 | 8595 |

| TangoWire – Gay | 1.89 | 359 |

| Tap That Guy | 0.45 | 287 |

| The DataLounge | 0.17 | 11,782 |

| The Gay Youth Corner | 0.88 | 5549 |

| The New Civil Rights Movement | 0.62 | 856 |

| The New Gay | 0.59 | 417 |

| Union Cafe | 7.06 | 16 |

| WickedGayBlog | 0.19 | 5473 |

| Windy City Media Group | 0.77 | 1681 |

| World of Wonder – WOW Report | 0.26 | 3458 |

| doorQ | 2.5 | 80 |

| qPDX: The Queer Northwest | 2 | 134 |

| the Celeb Archive | 0.44 | 7764 |

| wayoutwest.tv | 0.2 | 1013 |

| Main study | ||

| A Bears Life Magazine | 2.04 | 13 |

| AGB-Style | 3.33 | 101 |

| AKA William | 2.18 | 340 |

| ATLANTAboy | 0.76 | 131 |

| Another Guy Blog | 1.17 | 3037 |

| Antitwink | 8.85 | 56 |

| Antivirus Magazine Greece | 2 | 50 |

| Ask Gay Men | 1.32 | 2 |

| BEARNATION.us – Social Network | 5.14 | 142 |

| BGay.com | 5.96 | 94 |

| Back2Stonewall.com | 2.6 | 271 |

| Ben and Dave’s Six Pack | 4.05 | 74 |

| Best Gay News Magazine | 2.28 | 279 |

| BigJock | 3.76 | 60 |

| Blabbeando | 14.29 | 123 |

| Black Gay Gossip | 0.76 | 856 |

| Body and underwear Model | 1.49 | 3225 |

| BoyGush | 40.95 | 31 |

| Break the Illusion | 0.86 | 3239 |

| BuskFilms | 0.76 | 131 |

| ChicagoPride | 3.97 | 7 |

| Citizen Crain | 1.68 | 119 |

| Click Click Expose (LGBT Media) | 19.31 | 38 |

| Connexion | 2.61 | 86,832 |

| Costa Rica Gay Map | 1.45 | 69 |

| DRAMA DUPREE | 0.65 | 440 |

| DaSeekah | 0.42 | 3577 |

| Daddyhunt | 0.53 | 135,408 |

| David Dust | 1.86 | 325 |

| Deep Dish | 0.38 | 762 |

| Derek and Romaine | 9.09 | 8 |

| Easy Gay Life | 20 | 51 |

| Equalitopia | 4 | 15 |

| Fierth Magazine | 2.14 | 200 |

| FindFred | 7.4 | 40,102 |

| FocusBoy | 1.57 | 184 |

| G.I.R.L. – GayInternetRadioLive. | 0.2 | 5366 |

| GAN – Gay Ad Network | 16.67 | 3 |

| GUIDETOGAY.COM | 8.25 | 82 |

| Gay Authors | 4.29 | 1001 |

| Gay Cruising & Travel | 5.98 | 2636 |

| Gay Indo Forum | 1.97 | 19,081 |

| Gay List Daily | 0.45 | 221 |

| Gay Mexico Map | 0.94 | 6 |

| Gay Party List | 2.86 | 2 |

| Gay Rights Watch | 1.49 | 6 |

| GaySocialites | 6.5 | 223 |

| Gaycast | 1.47 | 238 |

| GaydarGuys | 0.52 | 525 |

| Going Nowhere Queerly | 100 | 2 |

| Golden Girls Forum | 0.54 | 249 |

| Good As You | 2.02 | 964 |

| HIVnet.com | 0.13 | 1 |

| Hit Dan Back | 0.65 | 2016 |

| Homorazzi Media | 2.45 | 2449 |

| Homotography | 1.93 | 12,166 |

| Homotron | 1.03 | 15 |

| Indusgay.com | 3.23 | 41 |

| Instinct Magazine | 1.91 | 1083 |

| InterstateQ.com | 1.54 | 36 |

| Joe.My.God. | 3.75 | 49,714 |

| JustGuys | 2.73 | 39,831 |

| LEATHERPOINT | 0.8 | 22 |

| LGBT News Agency | 5.26 | 6 |

| LGBTQ Nation | 7.79 | 146 |

| Lambda Literary Foundation | 2.08 | 545 |

| Lanzarote Gay Guide | 1.45 | 69 |

| Le Fag | 2.6 | 117 |

| MANofAUSTIN | 0.44 | 452 |

| Manjam | 3.32 | 38,518 |

| Mark’s List | 4.12 | 27 |

| Meet Gay Couples | 3.28 | 76 |

| Meet Gay Professionals.com | 21.28 | 78 |

| MegaMates Men | 34.27 | 10 |

| Michi & Michi | 16.67 | 85 |

| My Fabulous Disease | 6.07 | 72 |

| Nighttours | 0.93 | 7 |

| OHBoyMagazine | 20 | 28 |

| OUTTAKE BLOG™ | 25 | 4 |

| OUTview Online | 0.11 | 86 |

| Obama and the Gays | 33.33 | 3 |

| On Top Magazine | 2.56 | 3065 |

| One More Lesbian | 0.07 | 4941 |

| OneGoodLove – Gay | 2.28 | 9 |

| Out In America Cities Network | 1.68 | 9183 |

| OutLoudBlogs | 3.75 | 62 |

| OutTonight | 9.58 | 16 |

| Outsports | 5.77 | 2897 |

| Pams House Blend | 1.35 | 74 |

| Perfect Beat | 1.52 | 324 |

| Petrelis Files | 4 | 103 |

| Pink Kryptonite | 10.26 | 90 |

| Planet Homo | 10.84 | 34 |

| PopWired | 0.46 | 83 |

| Project Q Atlanta | 1.33 | 2946 |

| Project RunGay – Tom and Lorenzo | 0.29 | 105,146 |

| Provincetown Live | 22.22 | 9 |

| QNotes | 0.96 | 24 |

| Queerlife | 4.67 | 177 |

| ROD 2.0 | 2.46 | 785 |

| RealJock | 23.46 | 757 |

| Romanian Gay News Blog English | 0.24 | 316 |

| Rosie O’Donnell | 0.35 | 15 |

| Seattle Gay Scene | 3.81 | 160 |

| Sexy Men of Sports | 0.25 | 12 |

| SportsFags | 0.85 | 2850 |

| StiriGay.ro – Romanian Gay News | 6.27 | 2 |

| StudStop.com | 19.87 | 118 |

| THE QIT | 0.98 | 94 |

| Tabloid Prodigy | 1.3 | 4 |

| Tap That Guy | 0.58 | 2079 |

| The Beat San Francisco | 7.64 | 42 |

| The Bilerico Project | 2.83 | 2706 |

| The DataLounge | 0.17 | 120,647 |

| The Drag Queen Posse | 6.67 | 15 |

| The Gay Youth Corner | 0.86 | 20,120 |

| The Georgia Voice | 1.56 | 6 |

| The Gist | 0.53 | 92 |

| The Mad Professah Lectures | 0.35 | 1152 |

| The New Civil Rights Movement | 2.12 | 2843 |

| The New Gay | 31.22 | 520 |

| The Pretty Boys Club | 0.85 | 118 |

| The Queer Village | 1.72 | 374 |

| The Seafront Diaries | 3.8 | 1 |

| This Is FYF | 2.88 | 15 |

| Thought Theater | 4 | 3 |

| Top to Bottom | 3.06 | 81 |

| Unicorn Booty | 2.55 | 5772 |

| Union Cafe | 8 | 7 |

| Up Up and A Gay | 13.89 | 36 |

| VGL | 1.49 | 2722 |

| Velvet Dice Bag | 11.55 | 47 |

| WhatsTheT | 0.97 | 589 |

| WickedGayBlog | 0.74 | 4196 |

| Windy City Media Group | 3.27 | 452 |

| World of Wonder – WOW Report | 0.65 | 1 |

| doorQ | 4.02 | 561 |

| gaelick | 0.68 | 294 |

| gayborhood.tv | 36.87 | 14 |

| glbtq Encyclopaedia | 2.72 | 9 |

| homo-neurotic.com | 1.09 | 366 |

| qPDX: The Queer Northwest | 1.69 | 173 |

| the Celeb Archive | 7.69 | 43 |

| the L word Fan Site | 0.36 | 2602 |

| wayoutwest.tv | 7.27 | 1439 |

Appendix 2. Items used in survey

The following items ask about different types of pornography that you can access. Please indicate your preferences for the following options. Numbers closer to a description indicate more preference for that description. A number in the center means no preference for either. Here is an example:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Red | Blue | |||||

| Selecting ‘2’ means more preference for Red than Blue. | ||||||

| When searching for pornographic materials, do you prefer? | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Free | For pay | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Amateur | Professional | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Safer sex | Bareback | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Offline | Online | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Anonymous site | Membership site | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Actors doing things you would do | Actors doing things you wouldn’t do | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Generic looks | Specific looks | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| A mix of everything | Specific acts | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Vanilla | Kinky | |||||

| Is there anything else that you prefer when searching for pornographic materials? | ||||||

| 1 | Yes | |||||

| 2 | No | |||||

| −99 | RTA | |||||

Please specify what else you prefer to see:_______________

In the last question, you provided information on your preferences when searching for porn. We are also interested in how important those preferences are when you make a decision about which porn to use. Please rate the following characteristics on a scale from one (1) to nine (9), with one (1) being ‘most important’, and nine (9) being ‘least important’.

Cost (free vs. for pay)

Production (amateur vs. professional)

Condom use (safer sex vs. bareback)

Medium (offline vs. online)

Site type (anonymous vs. membership)

Taboo (actors doing things I would do vs. actors doing things I would not do)

Actors’ looks (generic vs. specific)

Behaviour (a mix of everything vs. specific acts)

Genre (vanilla vs. kinky)

[Other]

Footnotes

Notes on contributors

Dylan L. Galos is a doctoral student in epidemiology at the University of Minnesota. His research interests include HIV/STI prevention among MSM, alcohol and substance abuse, health disparities and social epidemiology.

Derek J. Smolenski received his MPH (Disease Control) and PhD (Epidemiology) from the University of Texas School of Public Health. His dissertation focused on refining the measurement of sexual health constructs salient to MSM sexual health such as internalised homonegativity. Dr Smolenski’s research interests include MSM sexual health, HIV/AIDS prevention and control, and internet sexuality.

Jeremy A. Grey received his PhD in Epidemiology at the University of Minnesota. His research interests include HIV/STI prevention among MSM, transgender health and online research methods. He is currently a Post Doctoral Fellow at Emory University.

Alex Iantaffi, PhD, LMFT, is an assistant professor in the Program in Human Sexuality in the Medical School at the University of Minnesota. His expertise includes sexual health, HIV prevention, sexual and gender minorities, relationships and family systems, disability, deafness, transgender health and identities, embodied psychotherapy and mindfulness.

B.R. Simon Rosser, PhD, MPH, LP, is professor and director of the HIV/STI Intervention and Prevention Studies (HIPS) Program in the Division of Epidemiology and Community Health at the University of Minnesota. He has advanced degrees in psychology, epidemiology and behavioural medicine, with postdoctoral training in clinical/research sexology.

References

- Alwin DF, Krosnick JA. The measurement of values in surveys: A comparison of ratings and rankings. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1985;49:535–552. [Google Scholar]

- Berg RC. Barebacking among MSM internet users. AIDS and Behavior. 2008;12:822–833. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9281-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg RC. Barebacking: A review of the literature. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2009;38:754–764. doi: 10.1007/s10508-008-9462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell CW. Men who have sex with men and recruit bareback sex partners on the internet: Implications for STI and HIV prevention and client education. American Journal of Men’s Health. 2008;2(4):306–313. doi: 10.1177/1557988307306045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll J, Padilla-Walker L, Nelson L, Olson C, McNamara Barry C, Madsen S. Generation XXX: Pornography acceptance and use among emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2008;23(1):6–30. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (MSM) 2010 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/msm/pdf/msm.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Condoms and STDs: Fact sheet for public health personnel. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/condomeffectiveness/latex.htm.

- Channel 1 Releasing. C1R.com – Store. Store. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.c1r.com/store.

- Cohen J. Weighed kappa: Nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychological Bulletin. 1968;70(4):213–220. doi: 10.1037/h0026256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- DCFUK!T . All about condoms [Motion picture] United States; no distributor: n.d. Retrieved from http://www.dcfukit.org/resources/all-about-condoms/ [Google Scholar]

- Del Barco M. Porn industry turned off by L.A. mandate for condoms on set. 2013 Jan 15; Retrieved from http://www.wbur.org/npr/169423027/porn-industry-turned-off-by-l-a-mandate-for-condoms-on-set.

- Duroy G. BelAmiOnline. BelAmiOnline.com. Nobody Does it Like BelAmi. 2013 Retrieved from http://tour.belamionline.com/clubtour.aspx.

- Eaton LA, Cain DN, Pope H, Garcia J, Cherry C. The relationship between pornography use and sexual behaviors among at-risk HIV-negative men who have sex with men. Csiro Sexual Health. 2011;9(2):166–170. doi: 10.1071/SH10092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escoffier J. Gay-for-pay: Straight men and the making of gay pornography. Qualitative Sociology. 2003;26(4):531–555. [Google Scholar]

- Grudzen CR, Elliot MN, Kerndt PR, Schuster MA, Brook RH, Gelberg L. Condom use and high-risk sexual acts in adult films: A comparison of heterosexual and homosexual films. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(S1):S152–S156. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.127035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hald G, Træen B, Noor S, Iantaffi A, Galos D, Rosser S. Does sexually explicit media (SEM) affect me? Assessing first person effects of SEM consumption among Norwegian men who have sex with men. Psychology and Sexuality in press. [Google Scholar]

- Hald GM, Malamuth NM. Self-perceived effects of pornography consumption. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37:614–625. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9212-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Parsons JT. Intentional unsafe sex (barebacking) among HIV-positive gay men who seek sexual partners on the Internet. AIDS Care. 2003;15:367–378. doi: 10.1080/0954012031000105423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes R, Prejean J, An Q, Lee LM, Janssen RS. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(5):520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt M. HIV scandal in gay porn industry. BBC News; 2008. Mar 4, [Google Scholar]

- Huebner DM, Proescholdbell RJ, Nemeroff CJ. Do gay and bisexual men share researchers’ definition of barebacking? Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality. 2006;18:67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Konstan J, Rosser BRS, Ross MW, Stanton J, Edwards WM. The story of subject naught: A cautionary but optimistic tale of internet survey research. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2006;10(2):00. [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek K, Beyer WJ, Weiss G, Iverson E, Kipke MD. In the dark: Young men’s stories of sexual initiation in the absence of relevant sexual health information. Health Education and Behavior. 2010;37(2):243–263. doi: 10.1177/1090198109339993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek K, Carpineto J, McDavitt B, Weiss G, Kipke M. Use and perceptions of the internet for sexual information and partners: A study of young men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010 Aug;31:1–14. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9666-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRue CC., Producer & Director . Shut your hole [Motion picture] Los Angeles, CA: Channel 1 Releasing; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mansergh G, Marks G, Colfax GN, Guzman R, Rader M, Buchbinder S. Barebacking’ in a diverse sample of men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2002;16:653–659. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203080-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison T. ‘He was treating me like trash, and I was loving it…’: Perspectives in gay male pornography. Journal of Homosexuality. 2004;47(3–4):167–183. doi: 10.1300/J082v47n03_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison TG, Morrison M, Bradley B. Correlates of gay men’s self-reported exposure to pornography. International Journal of Sexual Health. 2007;19(2):33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Lyons T, Garcia SC. Internet use and sexual health of young men who have sex with men: A mixed-methods study. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40(2):289–300. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9596-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Bimbi DS. Intentional unprotected anal intercourse among sex who have sex with men: Barebacking – from behavior to identity. AIDS and Behavior. 2007;11:277–287. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter J, Valkenberg PM. The use of sexually explicit internet material and its antecedents: A longitudinal comparison of adolescents and adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40:1015–1025. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9644-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Los Angeles Times; 2012. Nov 8, Porn industry declares war on new condom law. Retrieved from http://latimesblogs.latimes.com/lanow/2012/11/the-porn-industry-is-looking-for-ways-to-derail-a-voter-approved-ballot-measure-that-requires-actors-to-wear-condoms-during-f.html. [Google Scholar]

- Rich F. Naked capitalists: ‘there’s no business like porn business’. New York Times. 2001 May 20; Retrieved from: http://www.nytimes.com/2001/05/20/magazine/20PORN.html?pagewanted=all.

- Rosser BRS, Smolenski DJ, Erickson D, Iantaffi A, Brady SS, Galos DL, Wilkerson JM. The effects of gay sexually explicit media on the HIV risk behavior of men who have sex with men. AIDS and Behavior. 2013;17(4):1488–1498. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0454-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safer Sex in the Adult Film Industry Act. Chapter 11.39 Los Angeles County; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Silvera R, Stein DJ, Hagerty R, Marmor M. Condom use and male homosexual pornography. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(10):1732–1734. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.169912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinković M, Štulhofer A, Božić J. Revisiting the association between pornography use and risky sexual behaviors: The role of early exposure to pornography and sexual sensation seeking. The Journal of Sex Research, August 2012. 2012;50(7):1–10. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.681403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Educational Broadcasting Company (Utbildningsradion UR) Sex on the map – an animated sexuality education film for teenagers. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.rfsu.se/en/Sexualundervisning/RFSU-material/Sex-pa-kartan-filmen/

- Thomas J. Gay male video pornography: Past, present, and future. In: Weitzer R, editor. Sex for sale: Prostitution, pornography, and the sex industry. New York, NY: Routledge; 2000. pp. 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Titan Media. TitanMen. TitanMen Store. 2013 Retrieved from http://store.titanmen.com/

- Wilkerson JM, Iantaffi A, Smolenski DJ, Brady SS, Horvath KJ, Grey JA, Rosser BRS. The SEM risk behavior (SRB) model: A new conceptual model of how pornography influences the sexual intentions and HIV risk behavior of MSM. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2012 doi: 10.1080/14681994.2012.734605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]