Abstract

We studied young adolescents’ seeking out support to understand conflict with their co-resident fathers/stepfathers and the cognitive and affective implications of such support-seeking, phenomena we call guided cognitive reframing. Our sample included 392 adolescents (Mage = 12.5, 52.3% female) who were either of Mexican or European ancestry and lived with their biological mothers and either a stepfather or a biological father. More frequent reframing was associated with more adaptive cognitive explanations for father/stepfather behavior. Cognitions explained the link between seeking out and feelings about the father/stepfather and self. Feelings about the self were more strongly linked to depressive symptoms than cognitions. We discuss the implications for future research on social support, coping, guided cognitive reframing, and father-child relationships.

Keywords: adolescence, guided cognitive reframing, fathers, family conflict, Mexican American, depressive symptoms, externalizing behavior, stepfathers

The nature and implications of parent/stepparent-adolescent conflict have interested family researchers for over a century (e.g., Hall, 1904; Lichtwarck-Aschoff, Kunnen, & van Geert, 2009). Conflict during adolescence is more common than in earlier childhood (Granic, Dishion, & Hollenstein, 2003) and is related to less favorable adolescent adjustment over time (Gonzales, Deardorff, Formoso, Barr, & Barrera, 2006). However, much is still unknown about how adolescents manage conflict with the adults in their lives, especially the role played by others in helping adolescents to understand conflict events and the ethnic and cultural factors that might influence these interactions. Although the social support adolescents seek to cope with conflict is protective (Nomaguchi, 2008), to the best of our knowledge no studies have systematically explored what transpires when adolescents talk to others about conflict and what the consequences are for their cognitive interpretations, affect, and adjustment. We call this process guided cognitive reframing and, more simply, reframing. We explore who is sought out to reframe conflict, how those sources provide cognitive explanations for the situation, and the implications of that information for the adolescents’ affective evaluations of themselves and their co-resident fathers/stepfathers. Because many children reside with men who are not their biological fathers and because stepparent-child relationships tend to be more troubling to children, half of our families had a co-resident stepfathers and the other half of the sample had a co-resident biological father, and we explore how reframing operates within each father type. We also explored similarities and differences between families of Mexican and European ancestry using an analytic model to illustrate how adolescents use guided cognitive reframing to better understand conflict events.

Parent-adolescent conflict: Timing and culture

The adolescent transition is accompanied by increases in two notable qualities of the parent-child relationship: mutual disclosure and parental-child conflict (Lichtwarck-Aschoff et al., 2009). While sharing more information appears to be protective for children, conflict between parents and children can erode the quality of the relationship if it persists (Laursen & Collins, 1994) and is distressing to children even in small amounts (Chung, Flook, & Fuligni, 2009). However, contrary to the stereotype that the entirety of adolescence involves high levels of parent-child conflict (Freud, 1946; Hall, 1904), the peak for conflict appears to be early adolescence with conflict either remaining stable over time (Fuligni, 1998; Smetana, Daddis, & Chuang, 2003) or declining (Laursen, Coy, & Collins, 1998). Thus, early adolescence (as opposed to later adolescence) is an important period to investigate parent-child conflict processes.

In addition to the age of the child, the cultural context of families plays a role in the expression of and reaction to conflict within families. If parent socialization goals place an emphasis on values of accepting authority, promoting interpersonal harmony, or striving for group success, conflict with an authority figure may be considered disrespectful (Hofstede, 1980). Mexican American families tend to encourage such respect for authority figures (Keefe & Padilla, 1987). Not surprisingly, Mexican American adolescents report being discouraged from engaging in open communication about their parents’ behavior (Cooper, Baker, Polichar, & Welsh, 1993) and tend to use less eye contact with their parents than adolescents of European ancestry (Schofield, Castenada, Parke, & Coltrane, 2008). Whether an adolescent expresses frustrations or otherwise makes an attempt at communication may be explained by cultural social conventions that are associated with expressivity. Display rules are cultural conventions that influence whether and to what degree individuals manage emotional expression when communicating with others depending on social status, closeness, and context etc. (Matsumoto, 1990). Individuals closer in status to an adolescent (e.g., siblings, friends) are more likely to share intimate conversation than individuals who differ in social status to adolescents (e.g., parents, other adult relatives). Evidence from the acculturation and display rule literatures suggest adolescents of Mexican ancestry might be less likely to seek out their mothers and co-resident fathers/stepfathers than adolescents of European ancestry. However, in an earlier investigation (Cookston et al., 2012), greater endorsement of cultural values of familism, enculturation, or individualism by adolescents was not related to whether those adolescents were willing to seek out mothers, fathers/stepfathers, and other reframing agents. In the present investigation, we explore whether ethnicity determines who is sought out to reframe conflict, how those sources provide cognitive explanations for the situation, and the implications of that information for the adolescents’ affective evaluations of themselves and their co-resident fathers/stepfathers.

Social support and coping during adolescence

The literatures on coping strategies and social support suggest how adolescents might manage conflict in their lives. Coping strategies can be delineated to include both primary (direct) and secondary (indirect) methods (Connor-Smith, Compas, Wadsworth, Thomsen, & Saltzman, 2000). Primary coping strategies include techniques that bring one in contact with a stressor (such as employing appropriate emotion expression or problem-solving strategies) while secondary strategies allow one to adapt to the stressor. By comparison, disengaging from stress has been found to be associated with less favorable adaptation for adolescents in terms of higher alcohol consumption (Ohannessian et al., 2010) and depressive symptoms (Wadsworth, Raviv, Compas, & Connor-Smith, 2005). Thus, it appears that seeking out guidance to reframe family conflict may be protective for adolescents.

Research on the use of confidants has also provided guidance in understanding adolescent methods for addressing stress. During adolescence, mothers tend to be the primary confidants of youth while peers, siblings, romantic partners (Nomaguchi, 2008) and adults outside of the family (Beam, Chen, & Greenberger, 2002) are sought less often. However, adolescence is a period of transition from relying on parents as primary confidants to seeking out peers more often (Younnis, & Smollar, 1985) – a risky transition on average because peers tend to provide unconditional support rather than demand accountability (Nomaguchi, 2008). Additionally, a number of family-level factors explain whether adolescents talk with parents, namely, the quality of the parent-child relationship (Freeman & Brown, 2001), family structure (where children in married families communicate more with parents; e.g., Hetherington & Clingempeel, 1992), and child gender (where boys are less likely to seek support than girls; e.g., Windle, Miller-Tutzauer, Barnes, & Welte, 1991). Thus, it is important to understand whom adolescents seek out, what they learn from those encounters, and how they react to that information when making sense of conflict. We focus on understanding the psychological experience of seeking social support to cope with their co-resident father/stepfather-child conflict.

A focus on the co-residential father/stepfather-child relationship

Relationships between co-residential fathers/stepfathers and their children are complex, in part because men show higher levels of variability than mothers in the amount of face-to-face time they share with their children, how they engage with children, and in their beliefs about parenting (Leite & McKenry, 2002). Despite the diversity of children’s family experiences, fathers’ behaviors offer unique contributions to the well-being of children independent of the contributions of mothers (Amato & Riviera, 1999; Cookston & Finlay, 2006). Furthermore, many children today experience complex family living situations that may include (a) living with married (and increasingly cohabitating but unmarried) biological parents, (b) living in a divorced or separated family type in which primary contact is with the custodial biological parent with varying degrees of involvement with the other nonresidential biological parent, and (c) living with one biological parent and a stepparent (Kreider & Ellis, 2011). In our sample, we report on adolescents who live with a biological mother and either a biological father or stepfather, thus allowing us an opportunity to examine how reframing operates similarly and differently between the two types of father.

Prior work has documented clear differences between residential biological and residential stepfathers. Children are typically less close to their stepfathers than their biological fathers (Dunn et al., 2004), and stepfathers tend to be less involved in the daily lives of children than biological parents (Coleman & Ganong, 1997). Moreover, children in stepfather families tend to have less clarity about their role in the family (Belogai, 2010). However, other evidence shows that adolescents are protected when they feel important in the lives of their stepfathers (Schneck et al., 2009). Specifically, how much adolescents believe they matter to their co-residential fathers and stepfathers explains problem behaviors such as depressive symptoms and externalizing behaviors, exclusive of how much they believe they matter to their mothers. In an earlier investigation (Cookston et al., 2012), we found that whether the co-residential father was a biological father or a stepfather was not associated with whether children sought him out for guided cognitive reframing. However, because the current study is focused on what happens after the child seeks out the co-residential father/stepfather for conversation, we will test whether guided cognitive reframing operates differently for the two father types.

On the assumption that children may need outside input to understand their relationships with the men who live with them, this study investigated how early adolescents rely on others to reframe or reinterpret their co-resident father/stepfather’s conflict behaviors. To capture some of the diversity in father types, our sample includes children from two-parent intact families (mother and biological father) and two-parent stepparent families (mother and stepfather) because these family types represent the two largest groups of families in the United States in which a father is co-resident (Kreider & Rose, 2011).

Psychological process of guided cognitive reframing

The cognitive-motivational-relational theory of Lazarus (1991) states that in response to an emotion-evoking event, a cognitive appraisal of the event is first made regarding whether the conflict is self-relevant. If evaluated as self-relevant, a second appraisal is made about whether the conflict threatens or enhances one’s social status or view of oneself. Next, an attribution is developed about whether blame or credit should be assigned to the self or the other. Finally, a forecast of the future emerges which can be used to determine whether subsequent interactions will change for better or worse. Through this process, an individual cognitively evaluates an event and makes meaning about future contexts.

Applying Lazarus (1991) to the coping and social support literatures, we anticipate that when adolescents talk with others about conflict with father they will report healthier cognitive interpretations of a negative interaction. We believe this occurs in guided cognitive reframing to provide cognitions to explain 1) the reason for father/stepfather’s behavior and 2) whether he was at fault for the conflict. Following Lazarus, cognitions about the father/stepfather should be related to affective evaluations of the self and the father/stepfather. In this light, we view reframing as an active coping response to father-child conflict that relies on social support and assists adolescents in reappraising the nature of the relationship – a process we posit is likely dependent on who is sought to provide the information.

Sources of cognitive reframing

In response to a conflict event with a co-resident father/stepfather in two-parent families, an adolescent might seek a number of different people to reframe the stressful event. Specifically, the adolescent might seek out the source of the conflict (i.e., the co-resident father/stepfather), the mother, or possibly some other reframing agent. Given Greenberger and Chen’s (1996) evidence of the common and important role of non-parental confidants in the lives of adolescents, adolescents will likely seek out other sources in addition to parents. Non-parents offer an objective perspective and advice that may help the adolescent reframe the event. Beam and colleagues (2002) found that adolescents seek out sources outside of the home for support regardless of the quality of the adolescents’ relationship with parents. Adolescents appear to benefit from having individuals outside the family provide support, and we anticipated that this would be the case in our study. Thus, we hypothesized that more frequent reframing would be related to changes in the cognitive interpretations of conflict. Additionally, we anticipated that the reframing of the mother (more than the father) and that the mother and father (more than another source) would be related to better affective evaluations of the self and the father.

Present Investigation

In our tests of the context of guided cognitive reframing we explored whether the cognitive aspects of reframing (i.e., the reframer provides a reason, the reframer criticizes or defends the father) explain the link between frequently seeking out a source and an affective consequence of reframing (i.e., feeling better about dad, feeling better about the self). Additionally, to explore links between reframing and adjustment, we predicted concurrent externalizing behavior and depressive symptoms from the reframing variables. Finally, because our sample included families of European and Mexican American ancestry as well as families with a co-residential biological father or stepfather, we explored how these links differed by ethnicity and father status. While we anticipated more similarities between the four groups than differences, because Mexican Americans tend to endorse more hierarchy within families (Varela et al., 2004), we anticipated among the Mexican American parents that more frequent seeking out of the mother would be associated with her being less likely to blame father for his behavior. We also predicted that Mexican American fathers/stepfathers would be sought out less than European American fathers/stepfathers. Additionally, because mothers in stepfather families tend to advocate for the quality of the stepfather-child relationship (King, 2009), we expected that within stepfamilies, seeking out of mothers more often would be linked to her being more likely to support the father’s behavior while in biological father families more seeking out would be linked to the mother criticizing the father for his behavior. Finally, we anticipated that compared to biological fathers, stepfathers would be more likely to defend their behavior (rather than apologize).

Method

Participants

The participants were part of the Parent and Youth Study (PAYS), a sample of 392 (199 European American and 193 Mexican American) adolescents and both parents who were recruited from schools in Phoenix, AZ (52%) and Riverside, CA (42%). Participants represented intact families (both biological parents living together; 55.5%) and families with co-residential stepfathers. Most of the families were married (78.9%) but the stepfamilies were more likely to be unmarried (n = 72) than the intact families (n = 11) and the Mexican American families were more likely to be unmarried (n = 57) than the European American families (n = 26). For the stepfather families, the fathers averaged being co-resident with the child since age 6 (M = 6.49, SD = 3.09) and there were no differences between ethnicities regarding how long the stepfather was co-resident, F(1, 170) = .40, p = .53). One hundred eighty-eight of the adolescents were male (205 female) and all were in the 7th grade (M = 12.5; SD = 0.59). All data were collected during an in-person interview. The adjusted income for the sample ranged from $8,000 to $467,500 and averaged $67,410. Our European American families had a significantly higher income (M = $86,678, SD = $54,357) than our families of Mexican American ancestry (M = $47,543, SD = $26,521), but we have previously reported that this difference in income is representative of the ethnic groups within Census tracts from which they were sampled (Schneck et al., 2009). Sixty one percent of the fathers of Mexican ancestry were born in Mexico yet had lived in the United States an average of 16.39 years (SD = 7.97, range = 1 to 37). For a full description of the random sampling, see the following website: http://pays.sfsu.edu.

Measures

Sixteen items related to guided cognitive reframing were used in addition to items on child internalizing and externalizing behaviors. These items are discussed below.

Guided cognitive reframing

As part of a longer interview with 7th grade adolescents, their mothers, and their co-resident fathers (half of whom were stepfathers), we asked the adolescents sixteen reframing questions. Adolescents were first asked the following question about the residential father. “When you are upset with your (co-residential dad/stepdad) or about your relationship with him, do you ever talk to…” and indicated “yes”, “no” or “don’t know” for three sources of reframing: mom, resident dad/stepdad, and anyone else (including non-resident biological father). For each source of reframing that was endorsed, five follow-up items assessed the constructs in the hypothetical model of guided cognitive reframing.

Frequency of reframing

The first follow up question assessed the frequency of reframing by asking, “When you are upset with your (co-resident dad/stepdad), or bothered by his behavior, how frequently do you and [reframing source] talk about him?” Responses ranged from 1 (never) to 7 (always).

Cognitive experiences of reframing

Next, the adolescent was asked two questions about the cognitive experiences of reframing. First, how often the source of reframing provided a reason for the father’s behavior was assessed on a scale from 1 (never provides a reason) to 7 (almost always provides a reason) in response to the question, “When you and your mom have talked about your (co-resident dad’s/stepdad’s) behavior that is upsetting you, how often does she give you a reason for why he acted the way he did. Second, the adolescent was asked if the mother or preferred other person was more likely to criticize him or more likely to support him for what he said or did on a scale from 1 (very likely to criticize him) to 5 (very likely to support him). When using the co-resident father as the source of reframing, the adolescent was asked instead whether the co-resident father tended to, on a scale from 1 to 5, apologize for his behavior or admit he was wrong (1) to defend himself for what he said or did (5).

Affective consequences of reframing

The last two questions for both mother, co-resident father and preferred other asked about the affective consequences of the reframing incident for the adolescents based on (a) how they feel about themselves after speaking to the source of cognitive reframing with responses that ranged from 1 (a lot worse about yourself) to 5 (a lot better about yourself) and (b) how they feel about their co-resident fathers with responses that ranged from 1 (feel a lot worse about your co-resident dad/stepfather or your relationship with him to 5 (feel a lot better about your co-resident dad/stepfather or your relationship with him).

Externalizing behavior

Adolescents responded to 8 items on aggression and 4 items on delinquency from the Behavior Problem Inventory (Peterson & Zill, 1986). Responses ranged from 1 (not true) to 3 (very true) and included item stems such as, “In the past month you argued a lot” and “In the past month you stole at home.” Alpha for these items was .82 for the sample, and the scale score was calculated as the sum of the items such that higher scores indicated more externalizing behavior.

Child depression

Adolescent depressive symptoms were obtained from 8 items from the Child Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992). We shortened the scale from the longer 27-item scale using a rational method from data from a comparable project (e.g., reports from adolescents, mothers, fathers) in which all CDI items were entered as predictors in a stepwise regression predicting a total CDI scale score. The top seven items were chosen, as was the item assessing suicidal ideation. This new, shortened eight-item scale correlated .87 with the total CDI. For each symptom, participants indicated how closely they felt different symptoms of depression approximating a 3-point Likert scale. The score was scaled as the sum of the scores where higher scores indicated more depressive symptoms, alpha = .67.

Results

Our analyses included four stages. First, we were interested in which sources the adolescents sought out for cognitive reframing about the father-child relationship and demographic factors that impacted talking to each source. Second, we explored the descriptive patterns within our items. Next, we conducted path analyses within the context of reframing for each source to examine the relations among the frequency of reframing, the cognitive interpretations, and the affective sentiments (for self and father). Finally, we used path analysis to link each of the reframing constructs to concurrent psychological adjustment.

Testing for differences in reframing source

For adolescents who responded to the question, “When you are upset with your dad about your relationship with him, do you ever talk to…”, 294 adolescents confirmed they had spoken to their mother (76.2%), 162 had spoken to their co-residential father/stepfather (42.5%), and 203 had spoken to “anyone else” (52.3%). Regarding these other sources, the participants were more likely to speak about co-resident dad or stepfather with individuals who live in same household (n = 122), such as siblings (n = 92), which included stepsiblings (n = 13) and other children (n = 17). The next person an adolescent was likely to seek was a friend (n = 103); followed by extended family (n = 56), including grandparents (maternal grandparents n = 18, paternal grandparents n = 8, stepfather’s parents n = 3), aunt/uncle (mom’s side n = 17, dad’s side n = 4) and other relative adult (n = 6). Lastly, adolescents also spoke to professionals (n = 11), another non-relative (n = 7), and some of the adolescents in stepfather families spoke to their non-resident birth fathers (n = 14).

To test our hypothesis that more adolescents would seek out mothers more than fathers, we used a z-test for two proportions and observed that more adolescents sought out mothers than fathers (z = 7.42, p < .001) or other sources (z = 6.85, p < .001). Additionally, more adolescents sought out other sources than fathers (z = 2.65, p = .008). Adolescents in intact and stepfamilies did not differ in their rates of seeking out the mother (χ2 = .23, df = 1, p = .63) or another person (χ2= 1.05, df = 1, p = .305). However, as we predicted, fewer adolescents sought out co-resident stepfathers than sought out co-resident biological fathers (χ2= 6.83, df = 1, p = .009). Boys and girls were equally likely to seek out the mother and residential father (respectively, χ2= 1.25, df = 1, p = .264 and χ2= .14, df = 1, p = .707), however, girls were more likely to seek out someone else (χ2= 13.89, df = 1, p < .001). As we predicted, adolescents from Mexican American families were less likely to seek out the father than children from European American families (χ2= 6.41, df = 1, p = .011) and a similar trend appeared for seeking out mother (χ2= 3.19, df = 1, p = .074) with no differences for seeking out anyone else (χ2 = .01, df = 1, p = .927).

For the adolescents who endorsed seeking multiple sources, we explored whether the different sources were sought out more frequently. Three paired samples t-tests were computed for comparison using mother, father and preferred other as comparison targets. On average, participants did not significantly seek out mother (M = 4.42, SE = 0.12) with higher frequency than co-residential father/stepfather (M = 4.37, SE = 0.12, t (141) = .74, p > .05) or anyone else (M = 4.32, SE = 0.11, t (151) = .71, p > .05). Finally, no difference was found in the frequency of seeking out co-residential father/stepfather (M = 4.20, SE = 0.16) when compared to preferred other (M = 4.47, SE = 0.16, t (80) = .22, p > .05).

Descriptive patterns in reframing items

We also explored whether the reframing scores differed between our two ethnic groups and the two father types by testing multivariate general linear models for the indicators of guided cognitive reframing. Because only 27 adolescents indicated they had spoken to all three possible sources of reframing, we estimated separate multivariate models for father/stepfather, mother, and the other source across the five reframing items. For the 294 adolescents who indicated they had spoken to their mothers, we estimated multivariate tests on the 268 with complete data and found an overall main effect for differences between the co-residential biological and stepfathers (Wilks’ Lambda λ= .933, F(5, 260) = 3.755; p = .003) but no main effect for the two ethnic groups (Wilks’ Lambda λ= .971, F(5, 260) = 1.561; p = .171) or as an interaction between ethnicity and father type (Wilks’ Lambda λ= .979, F(5, 260) = 1.129; p = .345). When we examined the effect for father type, mothers in intact families were more likely to provide a reason for the co-resident father/stepfather’s behavior than were the mothers in the stepfather families. All significant univariate tests for the mothers are reported in Table 1. For the 151 adolescents who indicated they had spoken to their co-resident father/stepfather, we observed no differences between the co-residential biological fathers and the stepfathers (Wilks’ Lambda λ= .936, F(5, 143) = 1.971; p = .087), the two ethnic groups (Wilks’ Lambda λ= .952, F(5, 143) = 1.430; p = .271) nor did we observe an interaction between ethnicity and father type (Wilks’ Lambda λ= .947, F(5, 143) = 1.607; p = .162). Table 2 reports the significant univarate tests that followed the multivariate tests. For the 183 adolescents who indicated they had spoken to another source, we observed no differences between the co-residential father types (Wilks’ Lambda λ= .972, F(5, 175) = 1.008; p = .415) nor did we observe an interaction between ethnicity and father type (Wilks’ Lambda λ= .992, F(5, 175) = 0.292; p = .917), however, there was a multivariate trend for differences in the two ethnic groups (Wilks’ Lambda λ= .929, F(5, 175) = 2.690; p = .023). Subsequent univariate tests indicated that the other sources for the Mexican American adolescents were more likely to provide a reason for the behavior of co-resident fathers/stepfathers than the other sources of European American adolescents (Table 3).

Table 1.

Guided Cognitive Reframing by Mother with Family Type by Ethnicity Mean Scores Comparisons

| Indicators of Guided Cognitive Reframing | Family type | Mean (SD) | Main Effect by Ethnicity | Main Effect by Father Type | Ethnicity by Father Type Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Frequency of talking to mother Scoring: (1) never to (7) almost always |

EA/Intact | 4.49 (1.27) | ns | ns | ns |

| EA/Step | 4.34 (1.49) | ||||

| MA/Intact | 4.60 (1.30) | ||||

| MA/Step | 4.16 (1.40) | ||||

| Total | 4.41 (1.36) | ||||

| 2. Mother provides a reason Scoring: (1) never to (7) almost always |

EA/Intact | 5.25 (1.25) | ns | F(1, 264) = 18.79*** | ns |

| EA/Step | 4.65 (1.51) | ||||

| MA/Intact | 5.37 (1.14) | ||||

| MA/Step | 4.91 (1.33) | ||||

| Total | 5.07 (1.33) | ||||

| 3. Mother’s response to request for reframing Scoring: (1) very likely to criticize to (7) very likely to support father/stepfather |

EA/Intact | 3.15 (1.06) | ns | ns | ns |

| EA/Step | 3.24 (1.22) | ||||

| MA/Intact | 2.76 (1.01) | ||||

| MA/Step | 3.14 (0.95) | ||||

| Total | 3.07 (1.08) | ||||

| 4. Feel better about father/stepfather after reframing by mother Scoring: (1) a lot worse about relationship to (5) a lot better about relationship with father/stepfather |

EA/Intact | 4.09 (0.79) | ns | ns | F(1, 264) = 3.97* |

| EA/Step | 3.61 (1.06) | ||||

| MA/Intact | 3.76 (0.79) | ||||

| MA/Step | 3.77 (1.07) | ||||

| Total | 3.82 (0.98) | ||||

| 5. Feel better about self after reframing by mother Scoring: (1) a lot worse about self to (5) a lot better about self |

EA/Intact | 3.82 (0.98) | ns | ns | ns |

| EA/Step | 3.55 (0.82) | ||||

| MA/Intact | 3.81 (0.92) | ||||

| MA/Step | 3.75 (1.14) | ||||

| Total | 3.74 (0.97) |

Note: EA = European American; MA = Mexican American; Intact = two biological parent families; Step = the mother is a biological parent and the co-resident father is stepparent; N = 268 (n = 79 for EA/Intact; n = 62 for EA/Step; n = 70 for MA/Intact; n = 57 for MA/Step)

p < .05;

p < .001

Table 2.

Guided Cognitive Reframing by Father with Family Type by Ethnicity Mean Scores Comparisons

| Indicators of Guided Cognitive Reframing | Family type | Mean (SD) | Main Effect by Ethnicity | Main Effect by Father Type | Ethnicity by Father Type Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Frequency of talking to father Scoring: (1) never to (7) almost always |

EA/Intact | 4.01 (1.29) | ns | ns | ns |

| EA/Step | 4.52 (1.42) | ||||

| MA/Intact | 4.76 (1.35) | ||||

| MA/Step | 4.38 (1.15) | ||||

| Total | 4.58 (1.30) | ||||

| 2. He provides a reason Scoring: (1) never to (7) almost always |

EA/Intact | 5.53 (1.43) | ns | ns | ns |

| EA/Step | 5.19 (1.18) | ||||

| MA/Intact | 5.26 (1.36) | ||||

| MA/Step | 5.52 (1.18) | ||||

| Total | 5.40 (1.32) | ||||

| 3. Father’s response to request for reframing Scoring: (1) very likely to apologize to (7) very likely to defend himself |

EA/Intact | 2.07 (1.00) | ns | F (1, 147) = 5.47* | ns |

| EA/Step | 2.67 (1.21) | ||||

| MA/Intact | 1.97 (1.03) | ||||

| MA/Step | 2.24 (1.21) | ||||

| Total | 2.19 (1.10) | ||||

| 4. Feel better about father after reframing by father Scoring: (1) a lot worse about relationship to (5) a lot better about relationship with father |

EA/Intact | 4.26 (0.73) | ns | F (1, 147) = 7.43** | ns |

| EA/Step | 3.63 (1.04) | ||||

| MA/Intact | 4.18 (0.83) | ||||

| MA/Step | 3.96 (1.15) | ||||

| Total | 4.07 (0.93) | ||||

| 5. Feel better about self after reframing by father Scoring: (1) a lot worse about self to (5) a lot better about self |

EA/Intact | 4.05 (0.86) | F (1, 147) = 5.66* | F (1,147) = 4.51* | |

| EA/Step | 3.52 (0.98) | ||||

| MA/Intact | 4.09 (0.83) | ||||

| MA/Step | 4.21 (0.94) | ||||

| Total | 3.00 (0.91) |

Note: EA = European American; MA = Mexican American; Intact = two biological parent families; Step = the mother is a biological parent and the father is a non-biological stepparent; N = 151 (n = 61 for EA/Intact; n = 27 for EA/Step; n = 34 for MA/Intact; n = 29 for MA/Step)

p < .05;

p < .01;

Table 3.

Guided Cognitive Reframing by Other with Family Type by Ethnicity Mean Scores Comparisons

| Indicators of Guided Cognitive Reframing | Family type | Mean (SD) | Main Effect by Ethnicity | Main Effect by Father Type | Ethnicity by Father Type Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Frequency of talking to other Scoring: (1) never to (7) almost always |

EA/Intact | 4.46 (1.28) | ns | ns | ns |

| EA/Step | 4.58 (1.28) | ||||

| MA/Intact | 4.37 (1.27) | ||||

| MA/Step | 4.18 (1.34) | ||||

| Total | 4.40 (1.29) | ||||

| 2. Other provides a reason Scoring: (1) never to (7) almost always |

EA/Intact | 3.83 (1.71) | ns | ns | F (1, 179) = 6.33* |

| EA/Step | 3.74 (1.33) | ||||

| MA/Intact | 4.56 (1.36) | ||||

| MA/Step | 4.15 (1.66) | ||||

| Total | 4.09 (1.54) | ||||

| 3. Other’s response to father’s behavior Scoring: (1) very likely to criticize to (7) very likely to support father |

EA/Intact | 2.70 (1.10) | ns | ns | ns |

| EA/Step | 2.56 (1.22) | ||||

| MA/Intact | 2.83 (0.95) | ||||

| MA/Step | 2.69 (1.22) | ||||

| Total | 2.70 (1.11) | ||||

| 4. Feel better about father after reframing by other Scoring: (1) a lot worse about relationship to (5) a lot better about relationship with father |

EA/Intact | 3.83 (0.99) | ns | ns | ns |

| EA/Step | 3.63 (0.98) | ||||

| MA/Intact | 3.83 (0.86) | ||||

| MA/Step | 3.62 (0.94) | ||||

| Total | 3.74 (0.94) | ||||

| 5. Feel better about self after other reframing Scoring: (1) a lot worse about self to (5) a lot better about self |

EA/Intact | 3.79 (0.93) | ns | ns | ns |

| EA/Step | 3.81 (0.70) | ||||

| MA/Intact | 3.48 (1.04) | ||||

| MA/Step | 3.72 (1.00) | ||||

| Total | 3.69 (0.94) |

Note: EA = European American; MA = Mexican American; Intact = two biological parent families; Step = the mother is a biological parent and the father is a non-biological stepparent; N = 183 (n = 47 for EA/Intact; n = 43 for EA/Step; n = 54 for MA/Intact; n = 39 for MA/Step)

p < .01

Path Analysis Context of Reframing Models

Full information maximum likelihood models of the context of cognitive reframing were estimated in Mplus version 6 (Muthén & Muthén, 2010). Our analyses involved two stages. First, we were interested in the relationships among the reframing context variables so we estimated a series of path models that tested the anticipated links between the behavioral aspect of reframing (i.e., frequency of seeking out the reframing agent), the cognitive experiences of reframing (e.g., obtaining a reason), and the affective experiences of reframing (e.g., feelings about self). Specifically, we regressed (a) feelings about self and (b) feelings about father on the tendency of the reframing agent to (c) provide a reason for father’s behavior and (d) defend or rationalize father’s behavior. To test our expectation that frequent conversations were linked to affective responses through the cognitive reframing experienced, we tested whether we could drop the path from feelings about self or father on the frequency of seeking out the reframing agent. Second, we estimated separate models for each source of reframing (mothers, fathers, other source) because each model showed slightly different results. We also conducted multi-group analyses to explore differences by our four family types (i.e., European American intact families [EI], Mexican American intact families [MI], European American stepfamilies [ES], Mexican American stepfamilies [MS]). Our second set of models for each source of reframing predicted adolescent behavior problems from the context of reframing constructs. For these models, using Mplus we also estimated bootstrapped confidence limits around the mediated paths linking the reframing constructs to the adolescent outcomes.

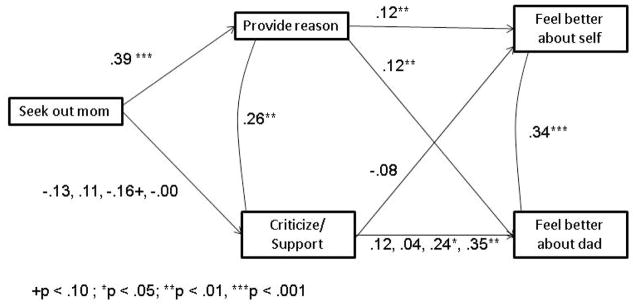

Mother

For the mother context of reframing constructs, a perfect fitting baseline model was estimated in which all paths were allowed to vary across the four groups and among the reframing variables. To test our cognition-affective prediction, we next dropped the path from the behavioral frequency of reframing variable to the measures of feelings about self and feelings about dad, and as we expected our more restrictive model observed good fit (χ2 = 4.95, df = 8, p = .76). Next, we equated the paths between each of the model variables across the four family types, evaluated model fit, and retained each constraint when model fit was not worsened. In our final model (χ2 = 25.24, df = 26, p = .51), 6 of the 8 paths were constrained across groups. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Path analysis model of guided cognitive reframing with mother. Single values indicate paths that were equated for our four groups (i.e., European American intact families [EI], Mexican American intact families [MI], European American stepfamilies [ES], Mexican American stepfamilies [MS]) while paths with four scores indicate paths that were estimated separately for the four groups. Note: sample size for EI = 84, ES = 69, MI = 72, MS = 60, respectively.

The two paths that worsened model fit when constrained for each family type were the associations between (1) feeling better about dad and whether mom criticized him and (2) the frequency of seeking out mom and mom’s criticism of dad’s behavior, thus, these paths were allowed to be free. Results showed that the more frequently mother was sought out to explain father’s behavior, the more likely she was to provide a reason (b = .39, p < .001). When mothers were more likely to give a reason, adolescents tended to feel better about themselves (b = .12, p = .01) and the fathers (b = .12, p = .002). Although the path between the frequency of seeking out mother and the likelihood she would criticize father could not be equated across groups, none of the correlations significantly differed from zero while slight differences existed in the patterns of the relations between groups. Contrary to our prediction, while the more frequently mother was sought out was associated with a likelihood that she would criticize the behavior of the father in the European American and Mexican American intact family groups (respectively, b = −.13, p = .15; b = −.17, p = .06), in the European American step families we observed a positive association (b = .11, p = .29) although none of these paths were significantly different than zero. The path between mother’s support of father’s behavior and feelings about father after talking with mother could also not be equated across groups. Positive associations were observed for all family groups for the link between mother’s higher levels of supporting father’s behavior and improved feelings about the child’s relationship with the father. However, this association was strongest for the Mexican American families (b = 12, p = .14 for EI, b = −.04, p = .71 for ES, b = .24, p = .021 for MI, b = .36, p = .02 for MS). Additionally, positive bidirectional associations were observed between the two cognitive reframing constructs (b = .26, p = .005) and between the two affective constructs (b = .34, p < .001). Tests of indirect associations suggested that the link between more frequent seeking out of mother related to feeling better and dad and self through being provided a reason for father’s behavior (b = .08, p < .001 for feeling better about self and b = .07, p = .003 for feeling better about the father).

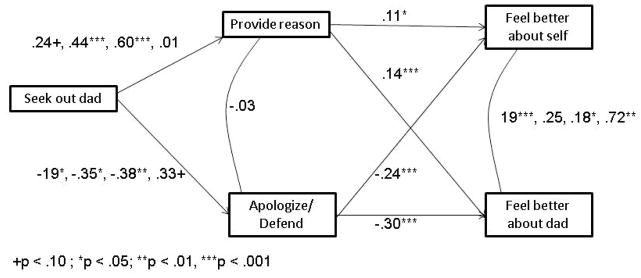

Father/Stepfather

For the context of reframing father/stepfather indicators, we first estimated a perfectly fitted saturated baseline model in which all paths were allowed to vary across the four family types and among the reframing variables. Next, we dropped paths from the behavioral frequency to the affective feelings about self and dad and this model observed good fit (χ2= 13.12, df = 8, p = .11). Next, the model was equated between each of the model variables across the four types of family, we evaluated model fit, and retained the released paths that notably worsened fit. The final model for father was constrained for five of the eight paths (χ2= 29.44, df = 23, p = .16). See Figure 2 for all paths.

Figure 2.

Path analysis model of guided cognitive reframing with father/stepfather. Single values indicate paths that were equated for our four groups (i.e., European American intact families [EI], Mexican American intact families [MI], European American stepfamilies [ES], Mexican American stepfamilies [MS]) while paths with four scores indicate paths that were estimated separately for the four groups. Note: sample size for EI = 84, ES = 69, MI = 72, MS = 60, respectively.

For all groups except for the Mexican-American stepfamilies, the more the adolescent discussed the father’s behavior with him the more likely he gave a reason for his behavior (b = 24, p = .07 for EI, b = .44, p = .001 for ES, b = .60, p < .001 for MI, b = .01, NS for MS). Contrary to our prediction, we did not observe unique links between the two ethnic groups or father types regarding whether more frequent reframing with mother and father was linked to a decreased likelihood of blaming the father for the conflict. Similar to the model for mother, the more the fathers provided reasons for his behaviors the better the adolescents felt about themselves (b = .11, p = .029) and their fathers (b = .14, p = .001). Moreover, for all but the Mexican American stepfamilies, the more the adolescents discussed the father’s behavior with him the more likely he would defend his behavior (b =− 19, p = .035 for EA, b = −.35, p = .020 for ES, b = −.38, p = .001 for MI, b = .33, p = .057 for MS). When the father defended his behavior, the worse the adolescents felt about themselves (b = −.24, p < .001) and their co-residential fathers (b = −.30, p < .001). Interestingly, no association was found between the cognitive reframing variables (b = −.03, NS) although the positive bidirectional association was found between the two affective variables (b = .19, p = .005 for EI, b = .25, p = .109 for ES, b = .18, p = .032 for MI, b = .72, p = .003 for MS). Tests of indirect associations demonstrated that the link between more frequent seeking out the co-residential father related to feeling better about both dad and self through being provided a reason for father’s behavior (b = .07, p = .015 for feeling better about self and b = .06, p = .043 for feeling better about the father) as well as co-residential father apologizing for his behavior (b = .08, p = .01 for feeling better about self and b = .07, p = .02 for feeling better about the father).

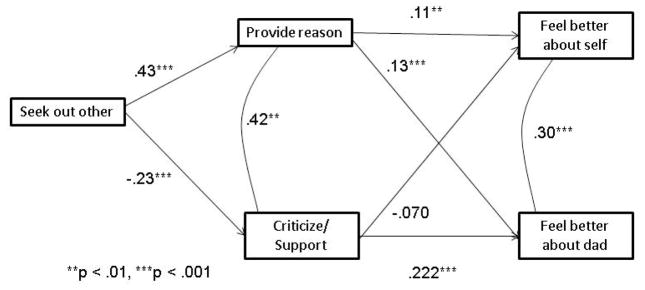

Other

For the context of reframing for the other source, a saturated baseline model was computed in which all paths were allowed to vary across the four groups and among the reframing variables and observed good fit. Next, we dropped the path from the behavioral frequency of reframing variable to the affective feeling variables and observed good fit (χ2 = 4.91, df = 8, p = .77). In the final model (χ2= 37.07, df = 32, p = .25), all 8 of the paths were constrained across groups, which was not observed to be significantly different than the less constrained model (χ2 difference = 32.16, df = 24, NS). See Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Path analysis model of guided cognitive reframing with other source. Single values indicate paths that were equated for our four groups (i.e., European American intact families [EI], Mexican American intact families [MI], European American stepfamilies [ES], Mexican American stepfamilies [MS]) while paths with four scores indicate paths that were estimated separately for the four groups. Note: sample size for EI = 84, ES = 69, MI = 72, MS = 60, respectively.

More frequent seeking the other source was associated with a greater likelihood of that person providing a reason for the co-residential father/stepfather’s behavior (b = .43, p < .001) and greater likelihood of criticizing the co-residential father/stepfather (b = −.23, p < .001). A non-significant path was found between the other supporting the father’s behavior and the adolescent feeling better about self (b = −.07, NS). However, the more a preferred other person provided support for the father the more likely the adolescent felt better about the co-residential father/stepfather relationship (b = .22, p < .001). If the other source provided a reason for the co-residential father/stepfather’s behavior the adolescents were more likely to feel better about themselves (b = .11, p = .004) and their co-residential fathers/stepfathers (b = .13, p < .001). Lastly, positive associations were observed between the cognitive reframing variables (b = .42, p = .003) and the affective variables (b = .30, p < .001). Tests of indirect associations demonstrated that the link between more frequent seeking out the other source related to feeling better about the self (but not the father) when the adolescent was provided a reason for the co-residential father/stepfather’s behavior (b = .07, p = .015 for feeling better about self) as well as when the other supported the co-residential father/stepfather’s behavior (b = −.07, p = .006 for feeling better about self).

Relations between Cognitive Reframing and Internalizing/Externalizing Behaviors

Finally, we were interested in whether the reframing constructs were related to concurrent adolescent reports of symptoms of depression and externalizing behaviors. Separate models were estimated for each source of reframing with the purpose of predicting internalizing and externalizing behavior. Additionally, to account for the role played by psychological constructs associated with problem behaviors, we predicted our child outcomes from our reframing variables after controlling for gender. Also, to account for comorbidity of symptoms, we also controlled the other problem behavior (e.g., externalizing behaviors predicted depressive symptoms). The models were computed independently for mother, father and a preferred other person and indirect links were also tested. For significant indirect paths, we also tested the alternative model that behavioral problems predict the mediator which, in turn, predict the reframing indicator. Only those variables that significantly predicted the outcome variables are reported below.

Depressive symptoms

For depressive symptoms when we estimated the co-residential father/stepfather model, higher levels of externalizing behavior were related to more depressive symptoms (b = .22, p < .001). Additionally, the better their relationships with the co-residential father/stepfather after a reframing event, the fewer symptoms adolescents reported (b = −.42, p = .02), and there was a marginal trend such that receiving a reason from father was associated with fewer symptoms (b = −.18, p = .09). We also observed an indirect path from co-residential father/stepfather apologizing for his actions and child feeling better about self and lower depressive symptoms (b = .08, p = .03), in turn, the more the co-residential father/stepfathers defended his actions, the less the child felt good about themselves. When we estimated the mother models for depressive symptoms, higher levels of externalizing behaviors were related to higher levels of depression (b = .30, p < .001) and the only reframing construct that related to depression was the adolescents’ feelings after reframing such that positive feelings were related to better adjustment (b = −.27, p = .04). Finally, when we estimated the model for the other source, greater support of the co-residential father/stepfather’s behavior by the other source was linked with fewer depressive symptoms (b = −.34, p = .02), being provided a reason was linked with more depressive symptoms (b = .18, p = .05), and feeling better about the relationship was linked with fewer symptoms (b = −.30, p = .07), after accounting for the links between higher depressive symptoms and more externalizing (b = .37, p < .001) and being male (b = .72, p = .02). We also observed an indirect path from more frequent conversations with the other source relating to that source criticizing the co-residential father/stepfather more which was linked to more depressive symptoms (b = .04, p = .05). No other indirect paths were observed, specifically the reverse path from depressive symptoms to criticism of the co-residential father by the other linking to more frequent conversations.

Externalizing behaviors

For the externalizing father models, we replicated the link between higher levels of externalizing behaviors and depressive symptoms (b = .44, p < .001). Furthermore, when adolescents reported that the co-residential father was less likely to provide a reason, they also reported more externalizing behaviors (b = −.48, p = .001) with no significant relations found for the other constructs. For the mother models predicting externalizing, we replicated the links between externalizing and depression (b = .79, p < .001), and feeling better about the relationship with the co-residential father/stepfather was linked with fewer externalizing behaviors (b = −.42, p = .05). None of the reframing constructs were related to externalizing symptoms in the model for the other source after establishing the links between gender (b = −1.84, p < .001) and depression (b = .78, p < .001).

Discussion

We tested the psychological process of guided cognitive reframing about conflict with co-resident fathers/stepfathers. Mothers were most likely to be sought by adolescents to discuss the co-residential father/stepfather relationship, followed by other sources, and co-resident stepfathers were least sought as agents of reframing compared to other sources. Affective feelings about self and the co-residential father/stepfather were more strongly related to the cognitive evaluations provided by the reframing agents than the frequency of seeking out the source of support. In turn, the affective responses to the reframing events tended to be better predictors of externalizing and internalizing behaviors than cognitive interpretations. Finally, although we observed some differences by ethnicity and stepfather status, the links among the reframing constructs tended to be similar across our four family types.

In support of our first hypothesis and past research (Hutchinson & Montgomery, 2007; Nomaguchi, 2008), adolescents were more likely to seek out their mothers than any other source. Non-parent sources were also sought more frequently than resident fathers and stepfathers. However, because half our resident fathers were stepfathers (who were sought out less than biological fathers) conclusions about the absolute frequency of seeking fathers must be considered in light of our sampling design. Boys and girls sought out their parents at equal rates, however, girls sought out other sources more often than boys. Furthermore, Mexican American adolescents tended to report seeking both mothers and fathers less than the adolescents of European ancestry although this link was less strong for mothers than fathers and there were no differences when seeking other sources. The research on Mexican American cultural family values suggests that the culturally informed expression of respect within families may prevent open communication about father’s behavior (Cooper et al., 1993). However, we found limited evidence for this conclusion in the present work as ethnicity accounted for very few differential associations. Additionally, in an earlier paper we did not find evidence that cultural values predicted whether fathers were sought out to discuss the father-child relationship (author citation removed), suggesting that the expression of respect may not result in differential guided cognitive reframing processes for adolescents of Mexican American and European ancestry.

Past research on coping has emphasized the degree to which strategies involve engagement or disengagement, and prior work on social support has focused on whether support is sought to accomplish goals (instrumental support) or to assist with emotional stress (affiliative). Our results offer a new perspective of guided cognitive reframing, a form of coping behavior emphasizing affiliative social support. From our perspective, guided cognitive reframing includes both primary and secondary coping features because it requires agency on behalf of the child to seek out support (i.e., primary coping) yet works optimally when seeking out the support results in changes in how the child thinks and feels about the father/stepfather-child relationship (i.e., secondary coping). Although our cross-sectional data preclude causal arguments, a number of common patterns emerged across the context of reframing results for our separate reframing agents. First, greater frequency seeking out a source of reframing was associated with that person providing a reason for the co-resident father/stepfather’s behavior. Thus, it appears adolescents obtain meaningful information from reframing agents to help them explain their co-resident father/stepfather’s behavior. However, we recognize it is also possible that because sources provide explanations they are sought out more often. Also, more frequent conversations about dad’s behavior were associated with that source tending to criticize him more often while the frequency of seeking out the co-resident father/stepfather tended to relate to him apologizing for his behavior. While it is possible that cognitive interpretations influence whether sources are sought, it appears that when adolescents seek out their residential fathers/stepfather he is more likely to apologize for his role in the conflict while conversations with individuals who are not the father/stepfather validate the adolescent’s view of the conflict. Two exceptions to these patterns existed for our Mexican American stepfamilies: more frequent conversations with father/stepfather were not associated with the adolescent being provided a reason nor were more frequent reframing events with mothers associated with her criticizing or supporting the behavior of the fathers/stepfathers. Additionally, for all three sources, obtaining a reason from a source of reframing was associated with feeling better about both the self and the father/stepfather; and, if father/stepfather apologized for his behavior, adolescents tended to feel better about their fathers/stepfathers. Clearly, the cognitive experiences of reframing – obtaining a reason for the father/stepfather’s behavior and understanding whether he was at fault – are linked to the affective consequences of reframing although our ability to make causal arguments is limited in the current design.

When we predicted adolescent depressive symptoms and externalizing behavior from our context of reframing constructs (and after controlling for child gender and comorbidity of symptoms), we found across all three sources that when reframing was associated with better feelings about the self then adolescents tended to have fewer depressive symptoms. This finding is important because it appears that talking to others about conflict with co-resident fathers/stepfather protects adolescents by promoting a more coherent self-image within the family context. Children react to witnessing parents argue by perceiving a threat to their emotional security as an expression of the attachment relationship (Cummings & Davies, 2010). Similarly, interactions about conflict with co-resident fathers/stepfathers appear to help adolescents resolve conflict related anxiety and, thus, buffer from depressive symptoms. Interestingly, having other sources support the father/stepfather’s behavior was also linked to fewer depressive symptoms, whereas non-parent sources providing a reason was linked to more depressive symptoms. Apparently, the other sources are providing a perspective that differs from the parents, suggesting the need to further explore the content and implications of those conversations for adolescent development.

We analyzed our models separately for the two independent variables upon which our sample was drawn: ethnicity (i.e., European American and Mexican American) and father status (i.e., biological father and stepfather). Of the 24 paths we tested for differences between the four groups, none occurred for the other source, five differed for the mother and father models with three of those differences in the model where father/stepfather was sought out. However, among these differences, the pattern of results was inconsistent and the differences we did observe did not closely align with past research on stepfather-child relationships. For example, correlations were different between two biological parent and stepfather families, correlations within groups tended to be non-significant. Although the results do not point to compelling differences in the process of guided cognitive reframing, we did not address every aspect of family conflict faced by stepfather families. Stepfather-child relationships are influenced by a number of factors (e.g., the length of time the father is in the home, involvement of biological father, stepfather’s personality, and stepfather and mother relationship), each of these relational components merit consideration in future investigations of this topic.

We also still need to know a great deal more about sources outside the family. Given that non-parental adults play an important role in the lives of adolescents (Greenberger & Chen, 1996) and the fact that peers tend to approve of one another’s behavior (Chen, Greenberger, Lester, Dong, & Guo, 1998), it appears qualities of the other source merit consideration in future studies of guided cognitive reframing. It has been argued that adult confidants primarily function to offer support (Greenberger, Chen, & Beam, 1998), however, that support may sometimes cast fathers/stepfather in a negative light and sometimes supports his behavior much like what we observed in the mother models.

Limitations and future research

Our study had a number of strengths. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first investigation of the cognitive and affective psychological experiences of guided cognitive reframing. We also explored whether these patterns differed between two ethnicities and two types of father (i.e., biological fathers and stepfathers), investigated if patterns were unique for different sources of reframing, and controlled for comorbidity and child gender when predicting problem behaviors. Despite these strengths and our exploration of a new topic area, our results were limited in a number of ways. First, our analyses were conducted using cross-sectional data taken when the adolescents were in the seventh grade. The link between adjustment and reframing is perplexing because the attributions adolescents make for the behaviors of others are influenced by the child’s depressive symptoms (Gladstone, Kaslow, Seeley, & Lewinsohn, 1997). Thus, it is possible that behavior problems and psychological symptoms may influence how often adolescents seek sources, the cognitive experience of talking with others, and the affective products of such discussions. We previously reported that whether adolescents showed more problem behavior was unrelated to seeking out sources for reframing (author citation removed to protect anonymity), thus it does not appear that more adjustment problems lead to more reframing. Similar patterns failing to link adjustment problems to reframing were observed in these results as well. Identification of other moderating factors that impact guided cognitive reframing could be useful guides for clinical applications and merit future study. Additionally, because our study focused on how adolescents use guided cognitive reframing to understand relationships with fathers, we did not obtain comparable data on how often guided cognitive reframing takes place to discuss concerns about conflict with mothers, peers, siblings, and others. In our study, the father was both the conflict partner and a possible reframing agent, and we observed that they were sought out less frequently than mothers or other sources. Possibly fathers/stepfathers are sought out more frequently when the source of the parent-child conflict is the mother or a peer, but future research will have to address this question. Possibly, individuals other than the father/stepfather are sought out because objective sources may be more likely to provide a reason for the father’s behavior whereas when fathers/stepfathers provide reasons for their behavior it may be interpreted as blaming the child. Future studies should focus on whether and how adolescents reframe mother-child relations, sibling relations, and other important relationships. Another limitation is our reliance on single-item indicators to assess aspects of the reframing context across reporters. Despite research showing that single-item measures are not characteristically unreliable (Frey & Cobb, 2010), we recognize that multiple item indicators would provide a more nuanced measurement of these psychological processes. One further limitation is that we did not consider whether these patterns differed by child gender and whether the other source was another adult or an age-mate such as a sibling or a peer. It is likely that guided cognitive reframing changes depending on the reframing agent’s experience with the conflict partner as well as experience in coping with distressing events. Finally, it is quite possible that sometimes adolescents are the initiating agents of the conflict and therefore responsible for conflict with their fathers/stepfathers. In turn, it is likely that guided cognitive reframing operates differently when adolescents are self-conscious of their roles in the conflict and future research should address whether the process works differently given the nature of the conflict and individual differences within adolescents along such relevant dimensions as locus of control. For example, perceptions of locus of control likely influence the explanations for father/stepfather behavior, including the belief that the father is to blame for all conflict situations as compared to a willingness to engage in the perspective taking necessary to take responsibility for ones actions. Likely, the explanations made by adolescents for the behavior of father/stepfathers influence how frequently parents and children engage in conflict, how they manage conflict, and whether reframing is viable for the family.

Conclusion

The adolescent transition has been characterized as a period of increasing family conflict and the acquisition of interpersonal strategies to cope with life events. Because the development of autonomy is an essential component of the adolescent transition (Steinberg, 2004) and exacerbates the discrepancies between parent and child beliefs (Smetana, 2002), it tends to also be accompanied by family conflict. However, less well understood are the psychological tools adolescents use to manage their anxiety about conflict. Although there were some limitations to our study, we provide the first view into the cognitive and affective responses to seeking out others to understand conflict with co-resident fathers/stepfathers. We found that the frequency of seeking out reframing agents was linked to whether the reframing agent provided a reason for the father’s behavior and whether the reframing agent supported the father’s behavior – two forms of cognitive interpretations – but that the frequency of seeking out an agent was unrelated to affective evaluations of either the self or the father/stepfather. Relatedly, the cognitive interpretations made by adolescents in reframing situations tended to be linked to the affective evaluations of the father and, to a lesser degree, evaluations of oneself. Finally, the feelings about the father that result from the reframing events tend to be linked to concurrent psychological adjustment more than the other aspects of reframing. These results provide new insights into what happens when adolescents seek out others to understand conflict with their fathers. Preventive interventions with families may be able to harness these findings to teach parents how to talk with their adolescents about family conflict as well as guiding adolescents in what to expect when they seek a source for input.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the families who participated in this study, the National Institute of Mental Health grant 5R01MH064829, and our many research assistants on the project.

Contributor Information

Jeffrey T. Cookston, Department of Psychology, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, CA 94132

Andres Olide, Department of Psychology, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, CA 94132.

Ross D. Parke, Department of Psychology, University of California, 900 University Avenue, Riverside, CA 92521

William V. Fabricius, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, 85287-1104

Delia Saenz, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, 85287-1104.

Sanford L. Braver, Department of Psychology, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, 85287-1104

References

- Amato PR, Riviera F. Paternal involvement and children’s behavior problems. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:375–384. [Google Scholar]

- Beam M, Chen C, Greenberger E. The nature of adolescents’ relationships with their ‘very important’ nonparental adults. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30(2):305–325. doi: 10.1023/A:1014641213440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belogai KN. Self-relation of adolescents in a family with a step-father. The Spanish Journal of Psychology. 2010;13(2):718–729. doi: 10.1017/s1138741600002389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Greenberger E, Lester J, Dong Q, Guo M. A cross-cultural study of family and peer correlates of adolescent misconduct. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34(4):770–781. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.4.770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung G, Flook L, Fuligni A. Daily family conflict and emotional distress among adolescents from Latin American, Asian, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(5):1406–1415. doi: 10.1037/a0014163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M, Ganong LH. Stepfamilies from the stepfamily’s perspective. Marriage and Family Review. 1997;26:107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Connor-Smith JK, Compas BE, Wadsworth ME, Thomsen AH, Saltzman H. Responses to stress in adolescence: Measurement of coping and involuntary stress responses. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:976–992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cookston JT, Finlay AK. Father involvement and adolescent adjustment: Longitudinal findings from ADD Health. Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research, and Practice About Men as Father. 2006;4(2):137–158. [Google Scholar]

- Cookston JT, Olide A, Adams M, Fabricius WV, Braver SL, Parke RD. Family conflict among Chinese and Mexican-origin adolescents and their parents. In: Juang L, Umaña-Taylor A, Jensen L, Larson R, editors. New Directions in Child and Adolescent Development. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2012. pp. 83–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper CR, Baker H, Polichar D, Welsh M. Values and communication of Chinese, Filipino, European, Mexican, and Vietnamese American adolescents with their families and friends. In: Shulman S, Collins AW, Shulman S, Collins AW, editors. Father–adolescent relationships. San Francisco, CA US: Jossey-Bass; 1993. pp. 73–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings E, Davies PT. Marital conflict and children: An emotional security perspective. New York, NY US: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J, Cheng H, O’Connor TG, Bridges L. Children’s perspectives on their relationships with their nonresident fathers: influences, outcomes and implications. Journal Of Child Psychology & Psychiatry. 2004;45(3):553–566. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00245.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman H, Brown B. Primary attachment to parents and peers during adolescence: Differences by attachment style. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2001;30(6):653–674. [Google Scholar]

- Freud A. The ego and the mechanisms of defense. New York: International Universities Press; 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Frey FM, Cobb AT. What matters in social accounts? The roles of account specificity, source expertise, and outcome loss on acceptance. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2010;40(5):1203–1234. [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ. Authority, autonomy, and parent-adolescent conflict and cohesion: A study of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, Filipino, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34(4):782–792. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.4.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladstone TRG, Kaslow NJ, Seeley JR, Lewinsohn PM. Sex differences, attributional style, and depressive symptoms among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25:297–305. doi: 10.1023/a:1025712419436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Chen C. Perceived family relationships and depressed mood in early and late adolescence: A comparison of European and Asian Americans. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:707–716. [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Chen C, Beam MR. The role of ‘very important’ nonparental adults in adolescent development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1998;27(3):321–343. [Google Scholar]

- Granic I, Hollenstein T, Dishion TJ, Patterson GR. Longitudinal analysis of flexibility and reorganization in early adolescence: A dynamic systems study of family interactions. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(3):606–617. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GS. Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion and Education. New York: D. Appleton & Co; 1904. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington E, Clingempeel W. Coping with marital transitions: A family systems perspective. Monographs Of The Society For Research In Child Development. 1992;57(2–3):1–242. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede G. Culture’s consequences: international differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills CA: Sage; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson M, Montgomery AJ. Parent communication and sexual risk among African Americans. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2007;29(6):691–707. doi: 10.1177/0193945906297374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe SE, Padilla AM. Chicano ethnicity. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- King V. Stepfamily formation: Implications for adolescent ties to mothers, nonresident fathers, and stepfathers. Journal Of Marriage And Family. 2009;71(4):954–968. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00646.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory. New York: Multi-Health Systems, Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kreider RM, Ellis R. Living Arrangements of Children: 2009. Current Population Reports. U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Collins WA. Interpersonal conflict during adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:197–209. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen B, Coy K, Collins WA. Reconsidering changes in parent-child conflict across adolescence: a meta-analysis. Child Development. 1998;69:817–832. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS. Emotion and adaptation. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lichtwarck-Aschoff A, Kunnen SE, van Geert PC. Here we go again: A dynamic systems perspective on emotional rigidity across parent–adolescent conflicts. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45(5):1364–1375. doi: 10.1037/a0016713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leite RW, McKenry PC. Aspects of father status and postdivorce father involvement with children. Journal of Family Issues. 2002;23(5):601–623. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto D. Cultural similarities and differences in display rules. Motivation and Emotion. 1990;14:195–214. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Sixth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nomaguchi K. Gender, family structure, and adolescents’ primary confidants. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70(5):1213–1227. [Google Scholar]

- Ohannessian C, Bradley J, Waninger K, Ruddy K, Hepp B, Hesselbrock V. An examination of adolescent coping typologies and young adult alcohol use in a high-risk sample. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2010;5(1):52–65. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson JL, Zill N. Marital disruption, parent-child relationships, and behavior problems in children. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1986;48:295–307. [Google Scholar]

- Schenck CE, Braver SL, Wolchik SA, Saenz D, Cookston JT, Fabricius WV. Relations between mattering to step- and non-residential fathers and adolescent mental health. Fathering. 2009;7(1):70–90. doi: 10.3149/fth.0701.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield TJ, Parke RD, Castañeda EK, Coltrane S. Patterns of gaze between parents and children in European American and Mexican American families. Journal Of Nonverbal Behavior. 2008;32(3):171–186. [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG. Culture, autonomy, and personal jurisdiction in adolescent-parent relationships. In: Reese HW, Kail R, editors. Advances in child development and behavior. Vol. 29. New York: Academic Press; 2002. pp. 51–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smetana JG, Daddis C, Chuang SS. “Clean your room!”: a longitudinal investigation of adolescent–parent conflict and conflict resolution in middle-class African American families. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2003;18:631–650. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Risk taking in adolescence: What changes, and why? In: Dahl RE, Spear L, Dahl RE, Spear L, editors. Adolescent brain development: Vulnerabilities and opportunities. New York, NY US: New York Academy of Sciences; 2004. pp. 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Varela R, Vernberg EM, Sanchez-Sosa J, Riveros A, Mitchell M, Mashunkashey J. Parenting style of Mexican, Mexican American, and caucasian-non-Hispanic families: Social context and cultural influences. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18(4):651–657. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.4.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadsworth ME, Raviv T, Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK. Parent and adolescent responses to poverty-related stress: Tests of mediated and moderated coping models. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2005;14:283–298. [Google Scholar]

- Windle M, Miller-Tutzauer C, Barnes GM, Welte J. Adolescent perceptions of help-seeking resources for substance abuse. Child Development. 1991;62(1):179–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]