Abstract

Refractory hypertension is an extreme phenotype of treatment failure defined as uncontrolled blood pressure (BP) in spite of ≥5 classes of antihypertensive agents, including chlorthalidone and a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist. A prospective evaluation of possible mechanisms of refractory hypertension has not been done. The goal of this study was to test for evidence of heightened sympathetic tone as indicated by 24-hr urinary (U-) normetanephrine levels, clinic and ambulatory heart rate (HR), HR variability (HRV), arterial stiffness as indexed by pulse wave velocity (PWV), and systemic vascular resistance (SVR) compared to patients with controlled resistant hypertension. Forty-four consecutive patients, 15 with refractory and 29 with controlled resistant hypertension, were evaluated prospectively. Refractory hypertensive patients were younger (48±13.3 vs. 56.5±14.1 years, p=0.038) and more likely female (80.0 vs 51.9 %, p=0.047) compared to patients with controlled resistant hypertension. They also had higher U-normetanephrine levels (464.4±250.2 vs. 309.8±147.6 μg/24h, p=0.03), higher clinic HR (77.8±7.7 vs. 68.8±7.6 bpm, p=0.001) and 24-hr ambulatory HR (77.8±7.7 vs 68.8±7.6, p=0.0018), higher PWV (11.8±2.2 vs. 9.4±1.5 m/s, p=0.009), reduced HRV (4.48 vs. 6.11, p=0.03), and higher SVR (3795±1753 vs. 2382±349 dyne·sec·cm5·m2, p=0.008). These findings are consistent with heightened sympathetic tone being a major contributor to antihypertensive treatment failure and highlight the need for effective sympatholytic therapies in patients with refractory hypertension.

Keywords: refractory hypertension, sympathetic activity, normetanephrines, arterial stiffness, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring

Refractory hypertension has been proposed as a clinical phenotype of antihypertensive treatment failure.1 The initial description of this phenotype was based on a retrospective analysis of patients referred to a hypertension specialty clinic for resistant hypertension.1 Of 304 consecutive patients with confirmed resistant hypertension, 29 patients, or approximately 10%, were identified as having refractory hypertension defined as failure to control systolic and diastolic blood pressure (BP) to less than 140/90 mm Hg after a minimum of 6 months of treatment by a clinical hypertension specialist. In that analysis, patients with refractory hypertension were receiving an average of 6 classes of antihypertensive agents, including the thiazide-like diuretic chlorthalidone and a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA), most often spironolactone. Patients with refractory hypertension manifested a consistently higher resting clinic heart rate (HR) compared to patients with controlled resistant hypertension. This elevation in HR was interpreted as evidence of heightened sympathetic tone, suggesting that increased sympathetic nervous system activity may play a potentially important role in the pathogenesis of antihypertensive treatment failure.

In a recent cross-sectional analysis of 14,809 hypertensive adults participating in the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study, refractory hypertension, defined as uncontrolled hypertension (>140/90 mm Hg) with use of ≥5 antihypertensive classes of agents, had a prevalence of 0.5% of all hypertensive participants and 3.6% of participants with resistant hypertension.2 African American race, male gender, obesity, chronic kidney disease (CKD), diabetes and history of stroke and coronary heart disease were associated with refractory hypertension in the REGARDS population. In this analysis, clinic HR was not higher in participants with refractory hypertension compared to all hypertensive participants or to participants with controlled resistant hypertension.

The current study was conducted to prospectively test for evidence of heightened sympathetic tone as indicated by 24-hr urinary normetanephrine levels, clinic and ambulatory HR, arterial stiffness, and peripheral vascular resistance in patients with refractory hypertension. In addition, brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and thoracic fluid content (TFC) were measured as indices of intravascular fluid volume. Contemporary patients also referred for resistant hypertension but whose BP was controlled with treatment, i.e., controlled resistant hypertension, served as a comparator group. The study design also allowed for prospective determination of the prevalence of refractory hypertension among patients referred to a hypertension specialty clinic for resistant hypertension.

Methods

Patient Identification

Consecutive patients referred to the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Hypertension Clinic for resistant hypertension (BP >140/90 mm Hg with use of ≥3 antihypertensive medications, including a diuretic) and who were subsequently diagnosed with refractory hypertension or controlled resistant hypertension were prospectively enrolled into the study protocol.

All referred patients underwent determination of aldosterone and cortisol status by measurement of plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC), plasma renin activity (PRA), and 24-hr urinary excretion of aldosterone, cortisol, sodium, potassium, and creatinine as part of their routine clinical care for resistant hypertension.3–5 Other secondary causes of hypertension were excluded as clinically indicated.5

Routine Treatment Approach

Patients were identified as having refractory or controlled resistant hypertension based on the BP in response to routine treatment provided by hypertension specialists. All patients referred for resistant hypertension were seen by 2 clinical hypertension specialists at every clinic visit. The patient’s antihypertensive medication regimen was revised according to routine clinical care if the clinic BP remained above goal.5 All patients were counseled to ingest a low salt/high fiber diet according to guidelines.5 The standardized treatment approach included, as needed to achieve BP control, initiating and maximizing doses of an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB); a calcium channel blocker (CCB) (most often amlodipine); preferential use of chlorthalidone as diuretic; addition of spironolactone (or eplerenone if spironolactone was not tolerated); preferential use of a combined alpha-beta antagonist (most often labetalol); addition of a centrally acting α2-adrenergic agonist (most often clonidine); and lastly, addition of a vasodilator (minoxidil or hydralazine). Loop diuretics were reserved for use in patients with clinical evidence of fluid retention.

After routine clinical follow-up of ≥3 visits over a ≥ 6 month, patients with refractory hypertension were identified. Refractory hypertension was defined as uncontrolled BP (>140/90 mm Hg) in spite of being adherent to a regimen that consisted of more than 5 classes of antihypertensive agents, including chlorthalidone 25 mg daily and a MRA (spironolactone 25 mg daily or eplerenone 50 mg twice daily) without evidence of underlying secondary causes of hypertension. Patients with controlled resistant hypertension, defined as controlled BP in the office with use of 4 or more antihypertensive agents per American Heart Association specifications were identified as control subjects.5

Controlled resistant and refractory patients were prospectively enrolled into the experimental protocol in a 2-to-1 fashion, i.e., 2 control subjects were enrolled for each subject enrolled with refractory hypertension. The control subjects were recruited from patients seen consecutively in clinic after enrolling each refractory subject. Patients were excluded from the study if there were signs and/or symptoms of heart failure (HF) or if having been hospitalized within 30 days for an acute episode of HF,6,7 atrial fibrillation, if there were concerns that that patient was non-adherent with the prescribed antihypertensive regimen, or if the patient had stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease (CKD).8

This study was approved by the UAB Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was obtained from all patients before study enrollment. The study was conducted according to institutional guidelines.

Patient Survey

All patients were surveyed and medical records were reviewed for estimated duration of hypertension and prior history of diabetes, dyslipidemia, coronary artery disease (CAD), stroke, and HF. During clinic visits, patients were routinely asked whether they have taken their antihypertensive medications regularly. Medication adherence was routinely assessed by the Morisky 8-Item Medication Adherence Questionnaire.9 Adherence was considered inadequate if patients scored >2 points.

Biochemical Testing

Biochemical evaluation per study protocol included measurement of 24-hr urinary normetanephrine levels, serum creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate10, serum potassium, BNP, and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP). Blood samples were obtained in the morning between 7–9 am at the study visit after overnight fasting and before taking the morning medication after being seated for 5 minutes.11 The 24-hr urine collections were done while patients were consuming their usual diet and without change in their level of physical activity. Adequacy of the 24-hr urine collection was assessed by measuring 24-hr creatinine excretion rates.

Clinic Blood Pressure Measurements

Clinic BP was measured by a hypertension specialist after at least 5 minutes of quiet rest in the sitting position with the back supported using the auscultatory method while supporting the arm at heart level during BP measurement. An appropriate sized cuff was used with a cuff bladder encircling at least 80 percent of the arm. Three BP readings were taken at intervals of 2 minutes by the physician and the second and third reading was used to average BP. The BP was measured in both arms and the arm with the higher BP was used for further BP measurements. All BP measurements were performed according to guidelines.5

Ambulatory Blood Pressure, Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability

All patients underwent 24-hr ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) to confirm uncontrolled BP in patients with refractory hypertension and to confirm controlled BP in patients with clinically controlled resistant hypertension. An automated, noninvasive, oscillometric device (Oscar 2, SunTech Medical, Inc. Morrisville, NC) was used to perform ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM).12,13 An appropriate sized cuff was used with a cuff bladder encircling at least 80 percent of the arm, according to guidelines.6 The first measurement was obtained in the clinic to ensure a proper function. Recordings were made every 20 minutes for the daytime (awake) and every 30 minutes for the nighttime (asleep) over a 24-hr period. Awake and asleep periods were defined individually according to the patient’s self-reported data. All patients took prescribed medications normally during ABPM, which were performed on working days, while usual activities were maintained. Standard calculations for ABPM were recorded. Valid 24-hr ABPM had to have recorded >80% of successful measurements. Controlled ambulatory BP was defined as mean 24-hr BP <130/80 mm Hg with a daytime (awake) BP of less than 135/80 mm Hg and a nighttime (asleep) BP of less than 120/70 mm Hg by ambulatory monitoring according to guidelines.12,13

Heart rate variability was estimated by calculating the standard deviation (SD) of daytime and nighttime heart rate values obtained with ABPM.14

Pulse Wave Analysis and Pulse Wave Velocity

All patients underwent applanation tonometry for measurement of carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (PWV) and central pulse wave analysis computed from the radial artery waveform using a transfer function (SphygmoCor, AtCor Medical, Sydney, Australia) according to guidelines.15,16 Pulse wave assessments were done during the same early morning session (7:00–9:00 am) after overnight fasting and before morning medication under standardized conditions. Both tests were performed with the patient in a supine position after resting for at least 10 minutes. Three measurements were acquired and the median was calculated.

Impedance Cardiography

Transthoracic impedance cardiography (ICG) (Bio-Z ICG, Sonosite Inc, Bothell, WA, USA), was performed in the same session to assess thoracic fluid content (TFC) during systole (synchronized electrocardiogram monitoring) and systemic vascular resistance by using bilateral neck and thoracic electrodes and a low voltage high amplitude alternating current to derive stroke volume.17–19

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data are expressed as mean ± SD. Categorical variables are expressed as percentages. Baseline variables for patients with refractory and resistant hypertension were analyzed by two-tailed Student t-test. Statistical significant level was set at P value ≤0.05. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Prevalence

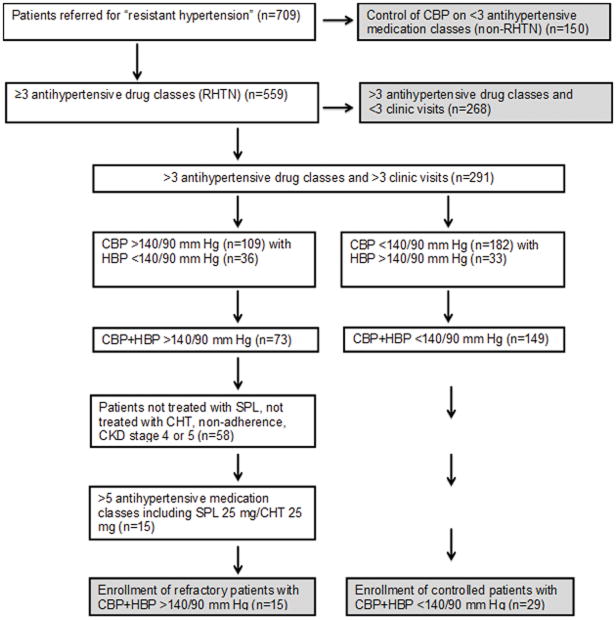

During the study period (1/2010–12/2012), 709 patients were referred to the UAB Hypertension Clinic for resistant hypertension. Of these, 150 patients were controlled on <3 antihypertensive medication classes and therefore identified as having controlled hypertension. The remaining 559 patients were confirmed to have resistant hypertension based on elevated clinic BP measurements while prescribed ≥3 different classes of antihypertensive agents, i.e., uncontrolled resistant hypertension (Figure 1). During follow-up, 276 patients were excluded from the analysis because of suspected medication non-adherence, control of BP on <5 medications, not receiving spironolactone or eplerenone, control of ambulatory BP, i.e., white coat resistant hypertension, presence of CKD stage 4, or 5, or inadequate follow-up (≤ 2 visits). Thus, >90% of patients initially suspected of having refractory hypertension were controlled with medication changes, were pseudo-refractory (non-adherent, white coat refractory), were lost to follow-up, or had uncontrolled hypertension in the setting of advanced CKD. Of the 559 patients confirmed to have resistant hypertension, 15 never achieved BP control in the office or by 24-hr ABPM despite treatment with maximum tolerated doses of at least 5 antihypertensive agents, including chlorthalidone and a MRA. These 15 patients were identified as having refractory hypertension, resulting in an overall prevalence 2.7% among patients originally referred for resistant hypertension.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of refractory hypertension

CBP, clinic blood pressure; CHT, chlorthalidone; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HBP, home blood pressure; RHTN, resistant hypertension; SPL, spironolactone.

Patient Characteristics and Comorbidities

Compared to patients with controlled resistant hypertension (n=29), patients with refractory hypertension were younger, more often female, had higher clinic BP, higher clinic HR, and were treated with more antihypertensive medications (Tables 1, 2 and S1), including greater use of treated of combined alpha-beta antagonists, CCBs, MRAs, alpha-2 adrenergic agonists, vasodilators, and centrally acting agents. There was no difference in use of ACEi/ARBs and thiazide or thiazide-like diuretics (Table 2, S1). Other characteristics, including race, body mass index (BMI), and duration of hypertension, were similar between the two groups. There was no statistically significant difference in comorbidities, including diabetes, CKD, CAD, or stroke. Patients with refractory hypertension did, however, have higher rates of prior hospitalization for HF (p=0.002).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients with Refractory and Controlled Resistant Hypertension

| Characteristics | Refractory hypertension (n=15) | Controlled RHTN (n=29) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 48.0±13.3 | 56.5±14.1 | 0.038 |

| Female (%) | 80.0 | 51.9 | 0.047 |

| AA race (%) | 60.0 | 55.2 | 0.765 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 32.4±7.1 | 32.6±7.0 | 0.942 |

| Number of antihypertensive medication drug classes at maximum dose | 6±1 | 4.1±1.1 | <0.05 |

| Clinic systolic BP (mm Hg) | 178.0±27.9 | 134.3±13.7 | <0.001 |

| Clinic diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 103.3±17.4 | 79.3±9.6 | <0.001 |

| Clinic heart rate (bpm) | 75.1±11.2 | 63.1±10.4 | 0.002 |

| Duration of hypertension (yrs) | 12.4±7.8 | 16.9±9.1 | 0.122 |

| Current smoker (%) | 13.3 | 10.3 | 0.784 |

| Diabetes (%) | 35.7 | 21.7 | 0.360 |

| CKD Stage 3 (%) | 35.7 | 28.6 | 0.652 |

| CAD (%) | 14.3 | 7.4 | 0.521 |

| Stroke (%) | 6.6 | 17.2 | 0.276 |

| OSA (%) | 41.6 | 63.6 | 0.180 |

| HF/hospitalization (%) | 40.0 | 0.0 | 0.002 |

| Morisky Score | 0.6 | 1.4 | 0.03 |

Values are expressed as mean ± SD or n (%).

AA indicates African American; BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure; CAD, coronary artery disease; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HF, heart failure; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea, RHTN, resistant hypertension.

Table 2.

Type of antihypertensive medications among adults with refractory and resistant hypertension

| Antihypertensive class | Refractory Hypertension (n=15) | Controlled RHTN (n=29) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACEi/ARBs | 100 | 100 | NS |

| BBs | 100 | 51.7 | 0.038 |

| CCBs | 100 | 75.9 | 0.038 |

| Thiazides/loop | 100 | 100 | NS |

| MRAs | 100 | 58.6 | 0.004 |

| α-2 agonists | 93.3 | 6.9 | <0.05 |

| Vasodilators | 60 | 13.8 | 0.001 |

Values are n=number (%).

ACEi, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; BB, beta blocker; RHTN, resistant hypertension; MRA, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist.

Biochemical Testing

The 24-hr urinary normetanephrine levels were significantly higher in patients with refractory hypertension compared to patients with controlled resistant hypertension (Table 3). The 24-hr urinary excretion of sodium was significantly lower in patients with refractory hypertension. Other measured biochemical parameters, including PAC, PRA, eGFR, BNP, hsCRP and 24-hr urinary aldosterone and cortisol excretion were not different between the two groups.

Table 3.

Biochemical characteristics of patients with refractory and controlled resistant hypertension

| Biochemical measures | Refractory hypertension (n=15) | Controlled RHTN (n=29) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 3.8±0.4 | 3.9±0.3 | 0.838 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.0±0.5 | 1.1±0.3 | 0.560 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 84.0±29.6 | 70.0±23.6 | 0.139 |

| BNP (pg/mL) | 45.4±48.2 | 63.0±74.6 | 0.958 |

| hsCRP(mg/L) | 7.7±11.0 | 11.4±23.6 | 0.698 |

| Aldosterone (ng/dL) | 9.9±6.9 | 11.6±11.6 | 0.376 |

| PRA (ng/mL/hr) | 2.8±4.3 | 1.14±1.17 | 0.230 |

| U-Aldosterone (μg/24h) | 11.6±8 | 12.3±7 | 0.829 |

| U-Cortisol (μg/24h) | 146.0±70 | 155.0±63 | 0.768 |

| U-Sodium (mEq/24h) | 122.7±54 | 186.0±100 | 0.024 |

| U-Normetanephrines (μg/24h) | 464.4±250 | 309.8±147.6 | 0.039 |

Values are mean ± SD.

BNP, Brain-type natriuretic peptide; RHTN, resistant hypertension; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; hsCRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; PRA, plasma renin activity.

Ambulatory Blood Pressure, Heart Rate and Heart Rate Variability

Daytime and nighttime periods were defined according to participants’ self-report. The average nighttime period based on patient diary was from 10 pm to 6 am. Mean daytime and nighttime systolic and diastolic BP levels were all significantly greater in the refractory patients compared to the patients with controlled resistant hypertension (Table 4). Likewise, mean daytime and nighttime HR was significantly higher in the refractory patients compared to controls. The largest difference in HR was during the daytime (82.1±11.5 versus 71.1±12.3 beats/min, refractory versus controlled resistant, p=0.012). Patients with refractory hypertension had significantly reduced HR variability compared to controlled resistant hypertensive patients (4.48 vs 6.11, p=0.036).

Table 4.

Clinic and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in patients with refractory and controlled resistant hypertension

| Parameter | Refractory Hypertension (n=15) | Controlled RHTN (n=29) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24-h systolic BP (mm Hg) | 174.0±20.2 | 139.8±16.3 | 0.0017 |

| Daytime | 178.1±97.4 | 141.0±15.7 | 0.0046 |

| Nighttime | 165.2±19.2 | 133.5±19.8 | 0.0002 |

| 24-h diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 94.7±19.8 | 75.7±11.8 | 0.006 |

| Daytime | 97.4±19.8 | 77.2±11.4 | 0.007 |

| Nighttime | 87.7±16.5 | 70.2±15.1 | 0.007 |

| 24-h PP (mm Hg) | 74.7±29.4 | 64.0±12.7 | 0.022 |

| Daytime | 80.0±21 | 64.0±12.6 | 0.022 |

| Nighttime | 77.5±18.5 | 63.6±14.7 | 0.03 |

| 24-h heart rate (beats/min) | 77.8±7.7 | 68.8±7.6 | 0.0018 |

| Daytime | 82.1±11.5 | 71.1±12.3 | 0.0118 |

| Nighttime | 72.7±9 | 65.6±9 | 0.038 |

| Heart rate variability | 4.48 | 6.11 | 0.036 |

Values are mean ± SD.

BP, blood pressure, RHTN, resistant hypertension; PP, pulse pressure.

Pulsatile Hemodynamic Parameters

PWV was significantly greater in the patients with refractory hypertension compared to those with controlled resistant hypertension (Table 5) indicative of greater arterial stiffness.15,16 Central systolic and diastolic pressures were significantly greater in refractory patients, as was the augmentation index (Table 5).

Table 5.

Results of pulsatile and impedance hemodynamics in patients with refractory and controlled resistant hypertension

| Parameters | Refractory Hypertension (n=15) | Controlled RHTN (n=29) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brachial artery measures | |||

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 75.0±11.7 | 63.0±10.4 | 0.002 |

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 177.2±28.9 | 133.6±13.1 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 101.4±16.5 | 79.3±9.6 | <0.001 |

| MAP (mm Hg) | 130.3±16.8 | 97.6±10.4 | <0.001 |

| PP (mm Hg) | 75.8±28.1 | 54.4±14.9 | 0.009 |

| Central aortic measures | |||

| Systolic BP (mm Hg) | 163.7±26.1 | 121.9±14.1 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mm Hg) | 103.3±16.7 | 80.1±9.8 | <0.001 |

| PP (mm Hg) | 60.4±26.9 | 41.8±14.0 | 0.034 |

| AP (mm Hg) | 18.9±12.7 | 10.7±10.1 | 0.07 |

| AIx (%) | 29.6±10.7 | 22.4±14.9 | 0.03 |

| AIx75 (%) | 30.9±6.7 | 16.8±12.0 | 0.004 |

| PWV (m/s) | 11.8±2.2 | 9.4±1.5 | 0.009 |

| Impedance measures | |||

| SVRI (dyne·sec·cm5·m2) | 3795±1753 | 2382±349 | 0.008 |

| TFC (/k ohm) | 32.3±5.4 | 31.8±7.1 | NS |

Values are mean ± SD.

Aix, augmentation index; AIx75, augmentation index standardized to a heart rate of 75 beats/min; AP, aortic pressure; BP, blood pressure; PP, pulse pressure; PWV, pulse wave velocity; RHTN, resistant hypertension; SVRI, systemic vascular resistance normalized for body surface area; TFC, thoracic fluid content.

Impedance Cardiography

TFC was similar in both groups. SVR index normalized for body surface area was 1.6 fold greater in patients with refractory hypertension compared to control patients (3795±1753 vs 2382±349 dyne· sec· cm5 ·m2, p=0.008, Table 5) in spite of greater use of vasodilators (Table 2, S1).

Discussion

The current study is the first prospective assessment of patients diagnosed with refractory hypertension, an extreme phenotype of antihypertensive treatment failure. Novel findings demonstrate that patients with refractory hypertension compared to patients with controlled resistant hypertension have: 1) greater 24-hr urinary normetanephrine levels, 2) increased arterial stiffness, 3) higher HR; 4) lower HR variability, and 5) higher SVR. Collectively, these findings implicate heightened sympathetic tone as an important cause of antihypertensive treatment failure.20–24 The prevalence of true refractory hypertension was only 2.7% of patients referred to a hypertension specialty clinic for resistant hypertension, considerably less than observed in a prior retrospective analysis.1 Combined, these findings indicate that true antihypertensive treatment failure is uncommon, but is characterized by biochemical and hemodynamic parameters consistent with excessive sympathetic output.

Prior studies clearly establish that increased sympathetic nerve activity (SNA) is associated with development and maintenance of arterial hypertension.25 Activity of the sympathetic nervous system increases progressively and in parallel with hypertension severity.26–30 In patients with resistant hypertension, catheter-based radiofrequency ablation of the renal nerves lowers BP concomitant with reductions in muscle SNA as measured by microneurography.31–33 The current findings add to this body of literature in suggesting that persistent sympathetic hyperactivity also contributes importantly to antihypertensive failure.

There is growing evidence that SNA may be associated with arterial stiffness and that the degree of sympathetic activation may influence arterial compliance.24–26 In an Italian study carried out in persons with unilateral lesions of the upper or lower extremity that required surgical intervention, reduction of adrenergic tone by ipsilateral brachial plexus anesthesia or ipsilateral removal of the lumbar sympathetic ganglia, resulted in markedly increased distensibility of the radial and femoral arteries, respectively.25

Furthermore, recent studies in normo- and hypertensive humans have shown that SNA is an independent determinant of PWV.24,26 Lastly, there is growing evidence that increased heart rate, a reliable marker of SNA and cardiovascular risk, is also an important determinant of arterial distensibility and PWV.26 Collectively, the current findings of higher HR levels, greater excretion of urinary normetanephrines, reduced HR variability, greater arterial stiffness, and increased vascular resistance support heightened sympathetic output as an important cause of refractory hypertension.

Certain clinical conditions and medications may alter measured levels of catecholamines and metabolites in plasma and urine.33 Drugs that inhibit central sympathetic outflow (e.g., clonidine, a drug that was used in the majority of refractory patients) decrease plasma catecholamine levels in normo- and hypertensive subjects, but have little effect on the excessive catecholamine secretion seen for example in patients with pheochromocytoma.33,34 Drugs that tend to increase plasma catecholamines (e.g., prazosin, β-blockers, and diuretics) do so only slightly.35

It is possible, however, that the higher 24-hr urinary normetanephrine levels observed in patients with refractory hypertension were due to greater use of vasodilators, which are known to increase sympathetic output. To evaluate this possibility we compared 24-hr urinary normetanephrine levels in the two study groups after excluding patients who were receiving hydralazine or minoxidil. Urinary levels of 24-hr normetaphrines remained significantly higher in the refractory patients compared to the controlled resistant patients suggesting the higher normetanephrine levels in the refractory patients was not related to use of vasodilators.

We also compared 24-hr urinary normetanephrine excretion in all of the patients with refractory and controlled RHTN who were receiving β-blockers. Higher 24-hr urinary normetanephrine levels were still observed in the refractory group in spite of use of β-blockers by both groups of patients suggesting a β-blocker independent increase.

Patients in the current study with refractory hypertension were characterized by increased vascular stiffness, as indexed by PWV, and central aortic BP, compared to patients with controlled resistant hypertension. While this is being described for the first time in association with refractory hypertension, the finding is consistent with prior evaluations of patients with uncontrolled resistant hypertension. For example, in the prospective community-based Maine Syracuse Longitudinal Study, a subgroup of 46 patients met the criteria for uncontrolled resistant hypertension i.e. elevated BP with use of ≥3 antihypertensive drug classes, including a diuretic.36,37 PWV was significantly higher in this group compared to a control group of 48 patients without resistant hypertension, i.e., BP controlled with ≤ 2 antihypertensive drug classes. Similarly, in a prospective evaluation of 90 Brazilian patients with resistant hypertension by Martins et al.38, 47 patients were classified as having uncontrolled resistant hypertension. PWV was significantly higher in this uncontrolled group compared to patients whose BP was treatment resistant but controlled.

In a prior retrospective analysis, we reported that patients with refractory hypertension had a consistently higher resting clinic HR compared to patients with controlled resistant hypertension.1 This elevation in HR was interpreted as evidence of heightened sympathetic tone, suggesting that increased sympathetic nervous system activity may play a potentially important role in the pathogenesis of antihypertensive treatment failure. The current prospective study confirms those earlier findings in demonstrating that clinic HR was again significantly higher patients with refractory versus controlled resistant hypertension. We further show that HR as measured during ambulatory monitoring is also significantly higher in refractory patients, particularly at night.

The current evaluation includes an estimate of SVR as measured by transthoracic ICG. Despite being on more vasodilators, a 1.6 fold higher SVR was observed in patients with refractory hypertension (Table 5). However, greater use of centrally acting agents in refractory hypertensive patients may have affected these results by increasing SVR.18

The validity of the calculation of cardiac output by ICG has limitations, including: 1) the difficulty of acquiring the signal because of spontaneous movements of the patient, disorders of heart rhythm and interference from electrical devices in the environment and 2) invalidation of the physical modeling of the system due to the presence of conditions like pregnancy, obesity, pleural effusion, chronic congestive heart failure with pulmonary edema or severe aortic valve disease that can change baseline thoracic impedence.18 In our study, participants were evaluated when clinically stable in normal sinus rhythm and without heart failure or clinical signs of volume-overload at the time of the study.18

An alternative hypothesis to refractory hypertension being neurogenic in etiology is it being secondary to inappropriate fluid retention. Such an effect is consistent with what has been described of resistant hypertension in general, i.e, being volume dependent. For example, Taler et al. utilized ICG to demonstrate that intensification of diuretic therapy based on high TFC values improved BP control rates in patients with resistant hypertension.39 To test this possibility, we measured BNP levels and TFC in patients with refractory and controlled resistant hypertension as indices of intravascular volume. We have previously reported that BNP levels do correlate with intravascular volume expansion in patients with resistant hypertension.40 Brain natriuretic peptide levels and TFC values were the same in the refractory patients and patients with resistant but well controlled hypertension. This argues against persistent fluid retention as being a major cause of refractory hypertension. The absence of a critical role of fluid retention in causing refractory hypertension has important clinical implications as it suggests that continued intensification of diuretic therapy, as is often suggested for lack of BP control, may not be appropriate or effective.

The current study confirms important negatives in terms of potential mechanisms of antihypertensive treatment failure, foremost being hyperaldosteronism. Aldosterone excess has been demonstrated in multiple studies to be an important contributor to resistant hypertension.5,41 However, aldosterone levels, both serum and 24-hr urinary levels, as well as the aldosterone-renin ratio were not different in patients with refractory versus controlled resistant hypertension. Furthermore, as previously shown, patients with refractory hypertension were unresponsive to use of a MRA1, along with all other classes of antihypertensive agents. Although aldosterone and renin activity are ideally assessed after the withdrawal of antihypertensive agents, this was not possible for safety reasons in these high-risk patients. Although β-blockers predictably suppress and diuretics, ACEi, ARBs increase PRA, effects on aldosterone release are minimal or absent.42 These observations suggest that while hyperaldosteronism may commonly contribute to antihypertensive treatment resistance, aldosterone excess is not likely a mediator of antihypertensive treatment failure in patients with refractory hypertension.

Likewise, lower levels of 24-hr urinary sodium excretion in patients with refractory hypertension argue against extreme dietary sodium excess as being the primary cause of refractory hypertension.

Indicators of mineralocorticoid excess other than aldosterone excess were not observed in patients with refractory hypertension. For example, biochemical abnormalities suggestive of apparent mineralocorticoid excess, (i.e., low PAC and low PRA) were absent. Similarly, comparable 24-h urinary cortisol levels did not suggest glucocorticoid excess (Table 3).

In the current prospective analysis, the overall prevalence of refractory hypertension was 2.7% of patients referred to a hypertension specialty clinic for resistant hypertension. Patients remained refractory to treatment despite being adherent to treatment regimens that included on average, 6 different classes of agents, including in all patients, use of a diuretic and a MRA. In our prior retrospective analysis, the prevalence of refractory hypertension was estimated at approximately 10% of patients referred to our hypertension specialty clinic with resistant hypertension.1 The lower prevalence observed in the current prospective analysis is likely attributable to a more systematic use of the combination of chlorthalidone and spironolactone. We and others have found this combination to be particularly effective for treatment of resistant hypertension.15

In the current analysis, all participants diagnosed with refractory hypertension were receiving diuretic and a MRA, whereas, during the time period of the retrospective analysis, the combination was used in only 1/3 of the patients designated as being refractory to treatment.

In this study, patients with refractory hypertension were more likely African American and female compared to subjects with controlled resistant hypertension, the latter difference being statistically significant. Similar observations were reported in the prior retrospective study of refractory hypertension.1 In the cross-sectional analysis of the REGARDS cohort, African American race and male gender were associated with higher risk of having refractory hypertension.2 Together, the findings of the 3 studies suggest that African Americans are more likely to have refractory hypertension, as is true of resistant hypertension6, while the association with gender, if any, needs clarification with additional studies.

The current study has some limitations, including 1) the reliance on patient report and an 8-item questionnaire for assessing medication adherence, both known to be of inconsistent reliability 2) use of greater number of classes and, in some cases, higher doses of antihypertensive agents in patients with refractory hypertension, which may have contributed to the higher urinary normetanephrine levels, and 3) the lack of a direct measure of sympathetic activity as with microneurography or norepinephrine (NE) secretion from sympathetic nerve terminals such as plasma NE with or without the spillover approach.

The current study is strengthened by its prospective design, rigorous comparison to patients with controlled resistant hypertension, and exclusion of common causes of pseudo-resistance, including white coat effect, inadequate treatment, and poor medication adherence.

Perspectives

In summary, refractory hypertension is being used to identify an extreme clinical phenotype of antihypertensive treatment failure, which in the present study was defined as BP that remains elevated in spite of use of at least 5 different classes of antihypertensive agents, including chlorthalidone and a MRA. The current findings demonstrate that true refractory hypertension is uncommon among patients originally referred to hypertension specialists for resistant hypertension. Refractory hypertension appears unique in terms of mechanism from the more common phenotype of resistant hypertension, with the latter being broadly attributed to inappropriate fluid retention, while the current results suggest that the former is more likely neurogenic in etiology. If true, such patients may preferentially benefit from treatment strategies that effectively reduce sympathetic output, if and when such strategies are available.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

1) What Is New?

This is the first prospective study that characterizes patients with refractory hypertension, a proposed novel phenotype of antihypertensive treatment failure.

2) What Is Relevant?

The current study demonstrates that heightened sympathetic tone as indicated by clinic and ambulatory HR, arterial stiffness, and 24-hr urinary metanephrine and normetanephrine levels may contribute importantly to antihypertensive treatment failure.

Summary

Refractory hypertension refers to an extreme clinical phenotype of antihypertensive treatment failure defined as elevated BP in spite of use of at least 5 different classes of antihypertensive agents, including chlorthalidone and a MRA. The phenotype appears distinct from resistant hypertension in general, which has been broadly attributed to inappropriate fluid retention, in that the current study findings suggest that refractory hypertension is more likely caused by excess sympathetic output.

Additional prospective studies are needed to further elucidate mechanisms of antihypertensive treatment failure. Patients with refractory hypertension may preferentially benefit from treatment strategies that effectively reduce sympathetic output, rather than intensified diuretic treatment. Clinically successful pharmacologic treatments that reduce sympathetic output, at least at doses that are well tolerated, are currently not available. Device-based procedures like renal denervation, although promising, have failed so far to show convincing blood pressure lowering effects in large, sham-controlled clinical trials. The current findings highlight the potential clinical need for effective sympatholytic therapies for patients with refractory hypertension.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

Research reported was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH 1R01 HL113004), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (UL1TR00165NIH), NIH T32 HL007457, and NIH T32HL079888.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Acelajado MC, Pisoni R, Dudenbostel T, Dell’Italia LJ, Cartmill F, Zhang B, Cofield SS, Oparil S, Calhoun DA. Refractory hypertension: definition, prevalence, and patient characteristics. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2012;14:7–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00556.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calhoun DA, Booth JN, 3rd, Oparil S, Irvin MR, Shimbo D, Lackland DT, Howard G, Safford MM, Muntner P. Refractory hypertension: Determination of prevalence, risk factors, and comorbidities in a large, population-based cohort. Hypertension. 2014;63:451–458. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young WF., Jr . Endocrine Hypertension. In: Melmed S, Polonsky KS, editors. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 2011. pp. 545–577. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart PM, Krone NP. The adrenal cortex. In: Melmed S, Polonsky KS, editors. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 2011. pp. 479–544. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calhoun DA, Jones D, Textor S, Goff DC, Murphy TP, Toto RD, White A, Cushman WC, White W, Sica D, Ferdinand K, Giles TD, Falkner B, Carey RM American Heart Association Professional Education Committee. Resistant hypertension: diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Hypertension. 2008;51:1403–1419. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.189141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, et al. Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology, Bax JJ, Baumgartner H, Ceconi C, et al. ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:803–869. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:1810–1852. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Kidney Foundation. KDOQI clinical practice guidelines for diabetes and CKD: 2012 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:850–886. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10:348–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2008.07572.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 10.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–470. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattsson C, Young WF., Jr Primary aldosteronism: diagnostic and treatment strategies. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2006;2:198. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Brien E, Parati G, Stergiou G, et al. European Society of Hypertension Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring. European Society of Hypertension Position Paper on Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring. J Hypertens. 2013;31:1731–1768. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328363e964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pickering TG. American Society of Hypertension Expert Panel: conclusions and recommendations the clinical use of home (self) and ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Am J Hypertens. 1996;9:1–11. doi: 10.1016/0895-7061(95)00341-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation. 1996;93:1043–1065. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laurent S, Cockcroft, Van Bortel L, Boutouyrie P, Giannattasio C, Hayoz D, Pannier B, Vlachopoulos C, Wilkinson I, Struijker-Boudier H. European Network for Non-invasive Investigation of Large Arteries. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2588–2605. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Bortel LM, Laurent S, Boutouyrie P, Chowienczyk P, Cruickshank JK, De Backer T, Filipovsky J, Huybrechts S, Mattace-Raso FU, Protogerou AD, Schillaci G, Segers P, Vermeersch S, Weber T Artery Society; European Society of Hypertension Working Group on Vascular Structure and Function; European Network for Noninvasive Investigation of Large Arteries. Expert consensus document on the measurement of aortic stiffness in daily practice using carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity. J Hypertens. 2012;30:445–448. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834fa8b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strobeck JE, Silver M, Ventura H. Impedance cardiography: noninvasive measurement of cardiac stroke volume and thoracic fluid content. Congestive Heart Failure. 2000;6:56–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2000.80144.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fellahi JL, Fischer MO. Electrical bioimpedance cardiography: An old technology with new hopes for the future. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2014;28:755–60. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2013.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldstein DS, Cannon RO, Zimlichman R, Keiser HR. Clinical evaluation of impedance cardiography. Clin Physiol. 1986;6:235–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097x.1986.tb00622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akselrod S, Gordon D, Ubel FA, Shannon DC, Berger AC, Cohen RJ. Power spectrum analysis of heart rate fluctuation: a quantitative probe of beat-to-beat cardiovascular control. Science. 1981;213:220–222. doi: 10.1126/science.6166045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barcroft H, Bonnar WM, Edholm OG, Effron AS. On sympathetic vasoconstrictor tone in human skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1943;102:21–31. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1943.sp004010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Esler M, Jennings G, Lambert G, Meredith I, Horne M, Eisenhofer G. Overflow of catecholamine neurotransmitters to the circulation: source, fate, and functions. Physiol Rev. 1990;70:963–985. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisenhofer G, Rundquist B, Aneman A, Friberg P, Dakak N, Kopin IJ, Jacobs MC, Lenders JW. Regional release and removal of catecholamines and extraneuronal metabolism to metanephrines. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:3009–3017. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.10.7559889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swierblewska E, Hering D, Kara T, Kunicka K, Kruszewski P, Bieniaszewski L, Boutouyrie P, Somers VK, Narkiewicz K. An independent relationship between muscle sympathetic nerve activity and pulse wave velocity in normal humans. J Hypertens. 2010;28:979–984. doi: 10.1097/hjh.0b013e328336ed9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Failla M, Grappiolo A, Emauelli G, Vitale G, Fraschini N, Bigoni M, Grieco N, Denti M, Giannattasia C, Mancia G. Sympathetic tone restrains arterial distensibility of healthy and atherosclerotic subjects. J Hypertens. 1999;17:1117–1124. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917080-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palatini P, Benetos A, Grassi G, Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Mancia G, Narkiewicz K, Parati G, Pessina AC, Ruilope LM, Zanchetti A European Society of Hypertension. Identification and management of the hypertensive patient with elevated heart rate: statement of a European Society Consensus Meeting. J Hypertens. 2006;24:603–610. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000217838.49842.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parati G, Esler M. The human sympathetic nervous system: its relevance in hypertension and heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1058–1066. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsioufis C, Kordalis A, Flessas D, Anastasopoulos I, Tsiachris D, Papademetriou V, Stefanidis C. Pathophysiology of resistant hypertension: the role of sympathetic nervous system. Int J Hypertens. 2011:642416. doi: 10.4061/2011/642416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grassi G, Cattaneo BM, Seravalle G, Lanfranchi A, Mancia G. Baroreflex control of sympathetic nerve activity in essential and secondary hypertension. Hypertension. 1998;31:68–72. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsukawa T, Mano T, Gotoh E, Ishii M. Elevated sympathetic nerve activity in patients with accelerated essential hypertension. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:25–28. doi: 10.1172/JCI116558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krum H, Schlaich M, Whitbourn R, Sobotka PA, Sadowski J, Bartus K, Kapelak B, Walton A, Sievert H, Thambar S, Abraham WT, Esler M. Catheter-based renal sympathetic denervation for resistant hypertension: a multicenter safety and proof-of-principle cohort study. Lancet. 2009;373:1275–1281. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60566-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Symplicity HTN-2 Investigators (CI Esler M) Renal sympathetic denervationin patients with treatment-resistant hypertension (The Symplicity HTN-2 Trial): a randomized controlled trial (Chief Investigator and Corresponding Author) Lancet. 2010;376:1903–1909. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hering D, Lambert EA, Marusic P, Walton AS, Krum H, Lambert GW, Esler MD, Schlaich MP. Substantial reduction in single sympathetic nerve firing after renal denervation in patients with resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2013;61:457–464. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bravo EL, Tagle R. Pheochromocytoma: State-of-the-Art and Future Prospects. Endocrine Reviews. 2003;24:539–553. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whiting MJ, Doogue MP. Advances in biochemical screening for phaeochromocytoma using biogenic amines. Clin Biochem Rev. 2009;30:3–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Najjar SS, Scuteri A, Shetty A, Wright JG, Muller DC, Fleg JL, Spurgeon HP, Ferruci L, Lakatta EG. Pulse wave velocity is an independent predictor of the longitudinal increase in systolic blood pressure and of incident hypertension in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1377–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.10.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elias MF, Sullivan KJ. Comment on optimal treatment for resistant hypertension: the missing data on pulse wave velocity. Hypertension. 2014;63:e16. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.02742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martins LC, Figueiredo VN, Quinaglia T, Boer-Martins L, Yugar-Toledo JC, Martin JF, Demacq C, Pimenta E, Calhoun DA, Moreno H., Jr Characteristics of resistant hypertension: aging, body mass index, hyperaldosteronism, cardiac hypertrophy and vascular stiffness. J Hum Hypertens. 2011;25:532–538. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2010.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taler S, Textor SC, Augustine JE. Resistant Hypertension: comparing hemodynamic management to specialist care. Hypertension. 2002;39:982–988. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000016176.16042.2f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gaddam KK, Nishizaka MK, Pratt-Ubunama MN, Pimenta E, Aban I, Oparil S, Calhoun DA. Characterization of resistant hypertension: association between resistant hypertension, aldosterone, and persistent intravascular volume expansion. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1159–1164. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calhoun DA, Nishizaka MK, Thakkar RB, Weissmann P. Hyperaldosteronism among black and white subjects with resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2002;40:892–896. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000040261.30455.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gallay BJ, Ahmad S, Xu L, Toivola B, Davidson RC. Screening for primary aldosteronism without discontinuing hypertensive medications: plasma aldosterone-renin ratio. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:699–705. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(01)80117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.