Abstract

Objective

A major focus of implementation science is discovering whether evidence-based approaches can be delivered with fidelity and potency in routine practice. This randomized trial compared usual care family therapy (UC-FT), implemented without a treatment manual or extramural support as the standard-of-care approach in a community clinic, to non-family treatment (UC-Other) for adolescent conduct and substance use disorders.

Method

The study recruited 205 adolescents (mean age 15.7 years; 52% male; 59% Hispanic American, 21% African American) from a community referral network, enrolling 63% for primary mental health problems and 37% for primary substance use problems. Clients were randomly assigned to either the UC-FT site or one of five UC-Other sites. Implementation data confirmed that UC-FT showed adherence to the family therapy approach and differentiation from UC-Other. Follow-ups were completed at 3, 6, and 12 months post-baseline.

Results

There was no between-group difference in treatment attendance. Both conditions demonstrated improvements in externalizing, internalizing, and delinquency symptoms. However, UC-FT produced greater reductions in youth-reported externalizing and internalizing among the whole sample, in delinquency among substance-using youth, and in alcohol and drug use among substance-using youth. The degree to which UC-FT outperformed UC-Other was consistent with effect sizes from controlled trials of manualized family therapy models.

Conclusions

Non-manualized family therapy can be effective for adolescent behavior problems within diverse populations in usual care, and it may be superior to non-family alternatives.

Keywords: adolescent mental health treatment, adolescent substance use treatment, family therapy, usual care, naturalistic study

This study tested whether family therapy, an evidence-based treatment approach for adolescent behavior problems, was more effective than non-family treatment when implemented as the routine standard of care in a community clinic. The emerging discipline of implementation science is focused on elucidating the conditions under which evidence-based interventions (EBIs) can be delivered with fidelity by front-line therapists and sustained over time in community settings (McHugh & Barlow, 2010). EBIs encompass both empirically supported treatments—i.e., manualized models and brand-name programs—and evidence-based practices—i.e., non-manualized, modular, or kernel/core interventions with strong empirical support (Chorpita, Daleiden, & Weisz, 2005; Embry & Biglan, 2008; Garland, Bickman, & Chorpita, 2010; Westen, Novotny, & Thompson-Brenner, 2005). The ultimate goals of implementation science are to determine whether EBIs can retain their effectiveness within various administrative and financial contexts of usual care (Weisz, Ugueto, Cheron, & Herren, 2013) and to develop reliable guidelines for balancing fidelity and adaptation so that EBIs remain viable, potent, and durable in everyday practice (McHugh, Murray, & Barlow, 2009).

Family Therapy is an Evidence-Based Approach for Adolescent Behavior Problems

One evidence-based treatment approach that is ripe for research on effectiveness under naturalistic conditions is family therapy (FT) for adolescent conduct problems, delinquency, and drug use. There are a handful of manualized FT models designed to treat adolescent behavior problems, notably brief strategic family therapy (BSFT), functional family therapy (FFT), multidimensional family therapy (MDFT), and multisystemic therapy (MST) (for reviews see Henggeler & Sheidow, 2012; Rowe, 2012). Although these brand-name models differ from one another along several dimensions of intervention focus and sequencing, they are common members of the broader FT approach, whose signature features include intervening directly with family members to repair intrafamilial relationships and addressing problems in the key extrafamilial systems within which family members live and develop. Manualized FT models have produced an exemplary record of treatment efficacy and effectiveness across the adolescent behavioral health spectrum and have reached the highest levels of empirical validation for disruptive behavior (Baldwin, Christian, Berkeljon, Shadish, & Bean, 2012; Chorpita et al., 2011) and substance use (Baldwin et al., 2012; Tanner-Smith, Wilson, & Lipsey, 2012). Studies have also reported reductions in internalizing symptoms and gains in prosocial functioning (see AUTHOR, 2009).

Barriers to Widespread Adoption of Manualized FT Models in Usual Care

Developers of the manualized FT models have made notable progress in disseminating their respective models by establishing purveyor-driven corporate entities that contract directly with host agencies to govern adoption activities (Henggeler & Sheidow, 2012). To support high-fidelity implementation, each model contains an extensive set of quality assurance (QA) procedures anchored by a lengthy treatment manual, standardized training toolkit, guidelines for ongoing training and observational consultation from model experts, and quality improvement methods that feed implementation data back to therapists and facilitate site recertification (e.g., Schoenwald, Sheidow, & Chapman, 2009). These purveyor-driven QA procedures are considered essential for effective model implementation and are required for proper credentialing in each of the respective manualized FTs.

These elaborate QA procedures also present three sizeable barriers to the feasibility of importing manualized FTs into community-based settings: (a) Cost: Purveyor contracts cost tens of thousands of dollars annually for initial training and certification maintenance (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2012). This is routinely affordable only for well-funded practice networks, principally government-operated sectors of care (e.g., juvenile justice, child welfare) in which clients are high risk, services are high cost, and stakes for success are high profile (Chambers, Ringeisen, & Hickman, 2005). (b) Flexibility: Manualized FTs feature highly structured intervention sequencing and require wholesale implementation of all treatment components. These model characteristics prohibit piecemeal implementation and selective treatment planning favored by many practitioners, and they discourage flexible use of discrete model components as auxiliary interventions for cases where conduct disorder and/or substance use are not primary referral problems (Chorpita et al., 2005). (c) Sustainability: Beyond cost, QA procedures for multicomponent FTs are difficult to sustain over time due to vicissitudes in local regulatory practices, reduction in purveyor commitment or availability, decrease in provider stamina to honor QA procedures for an extended period, and demoralization among line staff when external agents are responsible for ongoing judgments about clinical performance and intervention priorities (Gallo & Barlow, 2012). For all these reasons, importing and sustaining purveyor-driven FT models is beyond reach for most community providers (AUTHOR, 2013a).

Benefits of Testing Non-Manualized Family Therapy in Usual Care for Adolescent Behavior Problems

Given these sizeable barriers to adoption in community settings, it may not be realistic to expect that brand-name FT models and their elaborate QA procedures can be installed in every clinic that uses, or would like to use, the FT approach for treating adolescent behavior problems (ABPs). This dissemination shortfall begs the question: Is non-manualized FT—governed by core FT intervention principles and supported by routinely available intramural resources—a viable alternative to manualized models for treating ABPs in usual care? Although family-based services represent the most commonly endorsed approach in youth behavioral care (Hoagwood, 2005), the potency of the FT approach in naturalistic form remains unknown (Kaslow, Broth, Smith, & Collins, 2012). If the success of manualized FT depends upon the implementation boost provided by contracted QA procedures, then FT delivered without purveyor support may be ineffective. The current study addresses this issue by testing non-manualized FT delivered as routine care for ABPs.

The potential yield of testing EBIs in naturalistic settings seems more promising than ever given results from several effectiveness studies that compared manualized therapy against treatment as usual (TAU). For example in adult substance use, TAU has frequently produced outcomes on par with manualized treatments delivered by trained community therapists (e.g., Carroll et al., 2006; Miller, Yahne, & Tonigan, 2003; Morgenstern, Blanchard, Morgan, Labouvie, & Hiyaki, 2001). In youth mental health, two recent studies testing manualized cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) versus TAU, in which community therapists were randomly assigned to treatment condition, produced identical results: CBT and TAU showed equivalent improvement in depression (Weisz et al., 2009) and anxiety (Southam-Gerow et al., 2010), and treatment effects within both conditions were comparable to that documented in CBT trials involving research therapists. Using a similar design, Robbins et al. (2011) found that BSFT, implemented by community therapists with full QA support from model experts, performed equivalently to TAU in reducing adolescent drug use. These results remind us that relatively little is known about how EBIs perform in clinically representative conditions (Weisz et al., 2013b). Furthermore, although a few observational studies of TAU have reported little or no utilization of EBIs (e.g., Hurlburt, Garland, Nguyen, & Brookman-Frazee, 2010; Santa Ana et al., 2008), the evidence base in this area is quite limited, and it may be nonetheless true that usual care is more potent than commonly believed (Garland et al., 2010).

Study Hypotheses

The current study was a randomized naturalistic trial testing the FT approach versus non-family treatment for ABPs in usual care. Participants were inner-city adolescents assigned to one of two conditions: (1) Usual Care—Family Therapy (UC-FT): a single community clinic that practiced non-manualized, structural-strategic family therapy as the routine standard of care for youth behavior problems; (2) Usual Care—Other (UC-Other): a group of five treatment sites that collectively represent the most common venues for treating ABPs: community mental health clinics (CMHCs), outpatient psychiatry clinics, and drug counseling centers. As detailed below, no UC-Other site featured FT as a routine intervention approach.

There were three main hypotheses. First, because caregivers were expected to be regular participants in UC-FT sessions, we predicted that UC-FT would produce better treatment attendance than UC-Other. Second, based on recent studies examining EBIs in routine care for clinical youth, we predicted that youth in both conditions would show significant improvement at one-year follow-up for ABPs that were the primary reasons for referral: conduct problems and substance use. We also examined outcomes for internalizing symptoms, which were prevalent in the sample. Third, we hypothesized that UC-FT would produce superior gains to UC-Other, based on the exemplary track record of manualized FTs in comparative clinical trials (AUTHOR, in press a).

Method

Study Eligibility Criteria

Study eligibility criteria were: (1) adolescent age 12–18; (2) primary caregiver willing to participate in treatment; (3) adolescent met criteria for either the Mental Health (MH) or Substance Use (SU) study track (defined below); (4) adolescent not enrolled in any other behavioral treatment; (5) caregiver expressed desire, and adolescent expressed willingness, to participate in counseling; (6) family had health benefits that met the requirements of study treatment sites, all of which accepted a broad range of insurance plans including Medicaid. Exclusion criteria were: mental retardation or autism-spectrum disorder, medical or psychiatric illness requiring hospitalization, current psychotic symptoms, or active suicidal ideation.

Adolescents were placed in the MH track if they met diagnostic criteria based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR; American Psychiatric Association, 2000) for either Oppositional Defiant Disorder or Conduct Disorder, based on either adolescent or parent report. They were placed in the SU track if, based on adolescent report, they met these inclusion criteria: (1) reported at least one day of alcohol use to intoxication or illegal drug use in the past 30 days (or 30 days prior to living in a controlled environment), (2) endorsed one or more DSM-IV symptoms of Alcohol or Substance Dependence/Abuse, and (3) met ASAM criteria for outpatient SU treatment (American Society on Addiction Medicine, 2001). Youth who met criteria for both tracks were placed in the SU track.

Participants

Demographics, psychiatric diagnoses, delinquent activities and substance use, and other characteristics of the study sample (N = 205) are presented in Table 1 for the whole sample and separately by study track. Adolescents included both males (52%) and females and averaged 15.7 years of age (SD = 1.5). Self-reported ethnicities were Hispanic (59%), African American (21%), multiracial (15%), and other (6%). Caregivers who completed research interviews were 171 biological mothers, 7 biological fathers, 4 adoptive parents, 1 stepparent, 2 foster parents, 12 biological grandmothers, and 8 other relatives; household composition included 66% single parent, 26% two parents, 6% grandparents, and 2% other. As seen in Table 1, 130 (63%) participants qualified for the MH track and 75 (37%) for the SU track. There were a few differences between study tracks in demographics, with SU track adolescents being older, less likely to be Hispanic, and more likely to have a household member using illegal drugs. The only between-condition difference in demographics was that UC-Other adolescents were more likely to have a household member involved in illegal activities. Table 1 also shows several expectable differences between tracks in DSM-IV diagnostic rates, which were assessed by research staff using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI, Version 5.0; Sheehan et al., 1998); there were no between–condition differences in DSM-IV diagnoses.

Table 1.

Sample demographic and clinical characteristics: Full sample and study track differences

| Full Sample N = 205 |

MH Track n= 130 |

SU Track n = 75 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 52% | 50% | 55% |

| Adolescent age (M/SD)*** | 15.7 (1.5) | 15.3 (1.5) | 16.2 (1.3) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic* | 59% | 64% | 49% |

| Black | 21% | 20% | 21% |

| More than one race | 15% | 12% | 20% |

| Other race | 6% | 5% | 9% |

| Family Composition | |||

| Single parent | 66% | 66% | 65% |

| Two parents | 26% | 26% | 27% |

| Grandparent | 6% | 5% | 7% |

| Other | 3% | 3% | 1% |

| Family Characteristics | |||

| Caregiver graduated high school | 71% | 72% | 69% |

| Caregiver employed | 64% | 64% | 64% |

| Caregiver income greater than $15K | 55% | 50% | 64% |

| Caregiver receiving public assistance | 17% | 17% | 16% |

| Ever investigated by child welfare | 51% | 48% | 56% |

| Household member drug use** | 32% | 25% | 43% |

| Household member illegal activity | 19% | 16% | 23% |

| Adolescent Participation in Services | |||

| Past year Individualized Education Program | 30% | 29% | 33% |

| Past year educational intervention | 41% | 45% | 35% |

| Past year mental health treatment | 17% | 13% | 23% |

| Adolescent Psychiatric Diagnoses | |||

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | 87% | 88% | 85% |

| Conduct Disorder** | 53% | 44% | 68% |

| Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder | 74% | 73% | 75% |

| Depression Diagnosis | 42% | 40% | 45% |

| Substance Use Disorder*** | 28% | 5% | 69% |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder* | 17% | 13% | 24% |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 17% | 16% | 18% |

| More than one diagnosis | 89% | 87% | 92% |

| Adolescent Legal Issues | |||

| Picked up by police past year** | 31% | 23% | 44% |

| Probation/parole past year* | 7% | 5% | 12% |

| Number of delinquent acts past month (M/SD)** | 3.1 (3.0) | 2.5 (2.7) | 4.0 (3.4) |

| Days used substances past month (M/SD)*** | 3.2 (7.3) | .31 (1.1) | 8.3 (10.3) |

Note. All data reported are column percents, unless otherwise indicated.

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05

Study Procedures

The study was conducted under approval by the governing Institutional Review Board.

Participant recruitment

Research staff developed a referral network of high schools, family service agencies, and community programs serving youth in inner-city areas of a large northeastern city. Referral sources made referrals to research staff during site visits and also by phone and confidential email. Staff then contacted referred families by phone and offered them an opportunity to participate in a home-based screening interview to assess the reason for study referral and, if desired, to discuss enrollment in local treatment services.

Assessment, randomization, and linking to treatment

Study eligibility screening interviews were conducted primarily in the home but also in other locations upon request. Caregivers and adolescents were consented and interviewed separately; caregivers consented for themselves and their teenagers, and teenagers assented for themselves. Participants were informed that a federal Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health had been obtained to protect their confidentiality. Assessment measures consisted of a structured clinical interview and audio computer-assisted self-report measures. Caregiver assessments were administered in the preferred language: 77% English, 23% Spanish. Each member received an honorarium in vouchers for completing the interview, which typically lasted 60–90 minutes. At the completion of the screening interview, eligible families interested in attending treatment and completing follow-up research interviews were immediately offered participation in a baseline research interview, and for those interested, an appointment for the baseline was scheduled.

At the beginning of the baseline interview families were consented into the follow-up study using the same procedures described above for eligibility screenings, and baseline measures were administered using assessment procedures identical to those described above. Follow-up interviews were scheduled for 3, 6, and 12 months after the baseline interview date.

Randomization to study condition was revealed at the completion of baseline interviews. Urn randomization was used to promote balance between conditions on four variables: ethnicity (Hispanic, African-American, Other), sex, juvenile justice involvement (Yes, No), study track (MH, SU). One UC-Other site that specialized in addiction treatment was withheld from MH track cases, and one site that did not accept substance users was withheld from SU track cases.

Each family was assisted in completing its first intake session at the assigned treatment site using family linkage strategies (see McKay & Bannon, 2004) to counteract common barriers to enrollment. Linkage included several elements, implemented as needed: supporting the family via frequent phone calls or texting, brokering initial appointments directly with sites, ushering clients to first appointments, and helping to solve insurance problems. Linkage continued for every family until it completed the initial site intake session or dropped from the linkage process.

CONSORT Data: Participant Flow and Interview Completion Rates

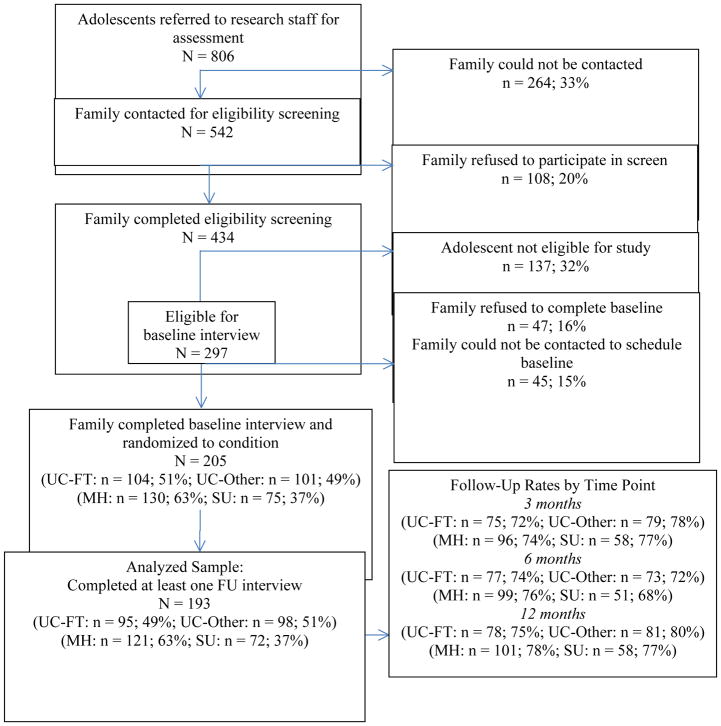

Adolescents were referred to the study primarily from schools (82%) but also from family service agencies (11%), juvenile justice or child welfare sources (4%), and other sources (3%). The CONSORT diagram (Figure 1) depicts the flow of participants into the study and the interview completion rates, separately by condition and track. There were several between-condition and between-track differences in participant flow: The un-contacted sample was older (t(736) = 3.77, p < .001) and had a higher proportion referred by schools (χ2(1) = 5.58, p < .05). The screen refuser group had a higher average age (t(501) = 2.05, p < .05) and higher proportion of females (χ2(1) = 10.30, p < .001) than screen completers. Several differences in demographic and diagnostic variables were found between the study sample versus the screen attrition sample: The study sample had a higher proportion of caregivers who graduated high school (χ2(1) = 6.69, p < .05) and more adolescents diagnosed with CD (χ2(1) = 15.94, p < .001), ODD (χ2(1) = 33.17, p < .001), ADHD (χ2(1) = 7.28, p < .01), and more than one diagnosis (χ2(1) = 29.81, p < .001). Overall follow-up interview rates were 91% in UC-FT and 97% in UC-Other and were not significantly different between conditions; overall follow-up rates were 93% for the MH track and 96% for the SU track and were not significantly different between tracks. Few participants were lost to follow up in either condition (9 UC-FT, 3 UC-OTHER) or track (3 SU, 9 MH), so that neither was tested for differential distributions of baseline characteristics.

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram

Treatment Conditions

All six treatment sites were outpatient clinical settings that accepted study cases as standard referrals. Sites were in close proximity and easily accessible via public transportation. No external training or financial support of any kind was provided to treat study cases, and therapists were not required to alter their clinical practices in any way. All therapists at each site who treated adolescent clients and who volunteered to participate were accepted into the study; based on site administrator report approximately 40–50% of therapists at each site volunteered (exact data were not available), and this percentage did not vary across site. Each site routinely prescribed weekly treatment sessions and offered in-house psychiatric support. Therapists at each site routinely received a comparable amount of weekly individual and/or group supervision. Details on site treatment practices are contained below in the Treatment Fidelity section.

Usual Care—Family Therapy (UC-FT)

The UC-FT condition consisted of a single CMHC that featured structural-strategic family therapy as the standard-of-care approach for behavioral interventions with youth. At no time had the site imported a manualized FT model or contracted for extramural implementation support. UC-FT therapists (n = 14) reported being licensed Marriage and Family Therapists (MFTs), social workers with family therapy training, or advanced trainees with family therapy experience. Site supervisors were all trained in the structural-strategic orientation (Haley, 1987; Minuchin & Fishman, 1981) that is a staple of FT practice in community-based youth services. All therapists received regular in-house training and supervision to promote family-based case conceptualization and use of structural-strategic FT treatment techniques. Participating therapists ranged in age from 28 to 59 years; 7 were female, 7 were Hispanic American, 1 was European American, and 1 from another racial background (note: demographic information was not collected on 5 UC-FT therapists). As a group they averaged 3.1 years (SD = 4.3) of postgraduate therapy experience.

Usual Care—Other (UC-Other)

This condition included a set of five clinics in order to sample the full spectrum of outpatient treatment options widely available for ABPs. Among the five UC-Other sites, two were CMHCs (9 study therapists total) with organizational profiles that basically matched the UC-FT site (see below descriptions of site organizational contexts). Two other sites were outpatient child psychiatry clinics (7 study therapists total) in teaching hospitals. The fifth site was an addictions treatment clinic (4 study therapists) containing an adolescent program that featured group-based treatment with supportive individual sessions. No site contained a supervisor or staff therapist who reported being a licensed Marriage and Family Therapist or completing a postgraduate training program in family therapy. Across the five sites, UC-Other therapists (n = 20) ranged in age from 24 to 45 years; 13 were female, 12 were European American, 2 were Hispanic American, 3 were Asian American, and 1 from another racial background (demographic information was not collected on 2 UC-Other therapists). As a group they averaged 3.2 years (SD = 2.8) of postgraduate therapy experience.

Treatment Fidelity and Site Organizational Contexts

UC-FT site adherence to signature FT Techniques

In a separate study (AUTHOR, 2013b) we utilized observational benchmarking analyses to compare FT fidelity scores for sessions previously held at the UC-FT site to fidelity scores from an efficacy trial of MDFT. We randomly selected 15 archived UC-FT treatment sessions videotaped on site prior to the start of the current study by a previous cohort of therapists. We coded these sessions for adherence to FT treatment techniques using the same validated FT observational fidelity measure previously used to code MDFT sessions from the trial (the fidelity measure and MDFT scores are detailed in AUTHOR, 2006). Among the signature FT techniques common to both structural-strategic therapy and the MDFT model, and coded for both samples, were: convening multiple family members in most sessions; specifying treatment goals that are family-based; working to bring about in-session change in family interaction patterns to decrease emotional negativity, increase positive attachments and communication, and improve family problem-solving; and intervening with caregivers to improve parenting skills. Then, using a probability sampling method known as statistical process control analysis (Deming, 1986), we plotted the within-sample variance in mean FT adherence scores for the UC-FT site against the “benchmark” adherence data produced by MDFT. The FT adherence measure contained a 7-point Likert-type rating scale with the following anchors: 1 = Not at all, 3 = Somewhat, 5 = Considerably, and 7 = Extensively. Scores for the UC-FT site (M = 3.4, SD = .51) clustered closely around the average score for MDFT (M = 3.5, SD = .60), and no score for any UC-FT session fell beyond two standard deviations of the benchmark MDFT mean. These analyses indicated that treatment delivered at the UC-FT site by a previous cohort of site therapists adhered closely to gold-standard fidelity levels for signature FT techniques achieved by a manualized FT model during a controlled efficacy trial.

Treatment differentiation: Therapist report

In previous research on the current study sample (AUTHOR, 2012), we examined fidelity data collected using a therapist self-report adherence measure that demonstrated strong construct, convergent, and discriminant validity. Examining 822 sessions across both study conditions, we found: (1) Prior to treating study cases, UC-FT therapists reported strongest allegiance and skill in FT techniques, whereas UC-Other therapists reported strongest allegiance and skill in CBT and motivational interviewing (MI). (2) While treating study cases, UC-FT therapists reported greater utilization of techniques associated with the FT approach than techniques associated with CBT, MI, or drug counseling; (3) UC-FT therapists reported significantly higher average use of FT techniques than the average level reported by UC-Other therapists, and this difference remained significant when the UC-Other sample was restricted to therapists from the two CMHC sites; (4) UC-Other therapists reported greater use of CBT, MI, and drug counseling interventions than did UC-FT.

Treatment differentiation: Observer Report

An observational study (AUTHOR, in press b) was completed on 157 sessions from the current study sample (104 UC-FT, 53 UC-Other) for which session recordings were available (the addictions treatment site was not represented because it did not permit session recordings). This study assessed the extent to which study sessions contained treatment techniques representing two evidence-based approaches for ABPs: FT and MI/CBT. MI/CBT interventions were assessed because, like FT, they are considered evidence-based approaches for treating ABPs (Chorpita et al., 2011; Tanner-Smith et al., 2012) and are widely endorsed in front-line settings (Cook, Biyanora, Elhai, Schnurr, & Coyne, 2010; Gifford et al., 2012). Observers used validated model-specific fidelity measures to rate the extent to which FT techniques (8 items; Cronbach’s α = .72) and MI/CBT techniques (8 items; Cronbach’s α = .62) were utilized in session based on a 5-point scale: 1 = Not at all, 2 = A little bit, 3 = Moderately, 4 = Considerably, 5 = Extensively. After controlling for individual therapist effects, UC-FT sessions received significantly higher ratings for FT interventions (M = 2.0; SD = .45) than for MI/CBT interventions (M = 1.6; SD = .40)(F(1, 102) = 50.6, p < .001, partial η2 = .33). In contrast, UC-Other sessions earned marginally higher ratings for MI/CBT interventions (M = 1.6; SD = .32) than for FT interventions (M = 1.4; SD = .36)(F(1, 51) = 3.64, p = .06, partial η2 = .07). [Note that averaged scale scores such as those reported here are not absolute barometers of strong EBI adherence, for at least two reasons: (1) For any given session, a therapist might receive a relatively high score on one or two items but low scores on all remaining items, producing a low mean score that masks extensive use of one or few techniques; (2) It is not typical or clinically advisable to extensively implement all or most techniques for any given approach in a single session.]

Session format and participants

At the end of each session study therapists were asked to document the session’s format (Individual/Family versus Group) and participants (adolescent, caregiver, and/or other person); previous research (AUTHOR, 2013c) indicates that therapists are highly reliable in documenting these features of treatment delivery. Within the UC-FT condition 100% of sessions were listed as Individual/Family; also, 75% of all sessions included the adolescent, 68% a caregiver, and 15% another person. Within the UC-Other condition, 85% of sessions were Individual/Family and 15% were Group; also, 96% of sessions included the adolescent, 15% a caregiver, and 1% another person (excluding other teens in group sessions). These data suggest that UC-FT emphasized family-involved work, whereas UC-Other produced a relative modicum of family-involved sessions.

Generalizability of site organizational contexts

The work context in each treatment condition was measured using the Organizational Social Context measure (Glisson & Green, 2005), completed by therapists at each site prior to treating study cases. All scales demonstrated adequate internal consistency (above .70) and intra-group agreement indices (above .70) across all sites, indicating that aggregation from individual-level to mean-level (i.e., organizational unit) descriptions is appropriate. Both conditions yielded scaled scores that were within two standard deviations of national norms for all scales in all domains: Organizational Culture (Proficiency: UC-FT = 12%, UC-Other = 32%; Rigidity: 50%, 58%; Resistance: 73%, 50%), Organizational Climate (Engagement: UC-FT = 66%, UC-Other = 64%; Functionality: 79%, 80%; Stress: 32%, 22%), and Work Attitudes (Morale: UC-FT = 58%, UC-Other = 52%). These data suggest the organizational contexts of the study conditions were consistently representative of contexts reported in the norming sample (100 CMHCs) and not substantially discrepant from one another.

Outcome Measures

Measures described below were all administered at baseline and 3, 6, and 12 months follow-up.

Externalizing and Internalizing behaviors

Adolescent and caregiver reports of youth externalizing and internalizing behaviors were assessed via the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; caregiver report) and the Youth Self Report (YSR). The CBCL and YSR are parallel measures of youth behavioral problems supported by extensive evidence of reliability, validity, and clinical utility (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) and used with a wide range of adolescent samples. Total scores on externalizing (oppositionality, aggression) and internalizing (depression, anxiety, somatization) summary scales were analyzed in this study.

Delinquency

Adolescent delinquency was assessed using the National Youth Survey Self-Report Delinquency Scale (SRD; Elliott, Huizinga, & Ageton, 1985), a well-validated instrument that has been used extensively with adolescent clinical samples (e.g., Sibley et al., 2010). Adolescents reported on the number of times they engaged in various overt and covert delinquent acts since the previous assessment timepoint.

Substance use

Substance use was measured with the Timeline Follow Back Method (TLFB; Sobell & Sobell, 1996), which assesses quantity and frequency of daily consumption of substances using a calendar and other memory aids to gather retrospective estimates. It is reliable and valid for alcohol and illegal drug use (Sobell & Sobell, 1996) and has proven sensitive to change in numerous studies with diverse adolescent samples (e.g., Liddle et al., 2008; Robbins et al., 2011; Waldron et al., 2001). Adolescents reported on the number of days they had used any alcohol or illegal drugs in each month of the follow-up period.

Statistical Analyses

For outcome analyses we used latent growth curve modeling (LGC: Duncan, Duncan, Strycker, Li, & Alpert, 1999) to examine the impact of treatment (UC-FT vs. UC-Other) on change over time in outcomes: externalizing symptoms, internalizing symptoms, delinquency, and substance use. Analyses were conducted using a 2 (study condition) by 4 (time) repeated measures intent-to-treat design. Missing data were handled with robust maximum likelihood estimation, assuming incomplete data were missing at random (Little & Rubin, 1987) based on evidence that missing assessments were not systematically related to the severity of adolescent problem behaviors (e.g., substance use and mental health symptoms) but rather were due to scheduling factors: Unable to be contacted (83% of missed assessments), refusal to continue in the study (14%), and adolescent placement in a secure facility (3%). LGC was conducted using Mplus version 7 (Muthen & Muthen, 1998–2012) and proceeded according to the following steps. First, we tested a series of growth curve models for each outcome, using likelihood ratio difference tests of nested models to determine the overall shape of the individual change trajectories, representing three possible forms of growth: no change, linear change, quadratic change. Next, we tested unconditional models for all outcomes to obtain the average effect for change over time in outcome without including study condition or other covariates. Third, we added study condition (UC-FT vs. UC-Other) and study track (MH vs. SU) to the models to test the impact of each on initial status and change over time (i.e., the intercept and slope growth parameters). Given that FT was implemented at only one site, we did not include Site as a covariate in these analyses because (1) it was not possible to model an average site effect for the FT condition and (2) modeling covariate Site effects under these conditions would have severely hampered our ability to find the between-condition effects that were of primary interest. Also, there were too few participants at each UC-Other site to replicate study analyses in the form of unbalanced comparisons between UC-FT versus single UC-Other sites or versus subgroups of UC-Other sites (Note: Implications of the confound between treatment condition and site are discussed below in the Limitations section). We also tested condition by track interactions, and if significant, re-ran the model separately for MH and SU track participants to test simple effects. Treatment effects were demonstrated by a statistically significant slope parameter, as tested by the pseudo z test—calculated by dividing the coefficient by its standard error—associated with study condition. In this third step, all models adjusted for three covariates: adolescent sex, age, race/ethnicity. To control for potential variability in client outcomes achieved by different therapists within each condition, we used the sandwich variance estimator (Diggle, Heagerty, Liang, & Zeger, 2002), which uses random effects modeling to produce corrected standard errors in the presence of data that are nonindependent due to nested structures—in this case, clients nested within therapists.

For normally distributed outcomes (adolescent- and caregiver-reported externalizing and internalizing symptoms), we used conventional LGC models for continuous outcomes. For outcomes that deviated substantially from normality (delinquency and substance use), we used two-part growth curve models (Brown, Catalano, Fleming, Haggerty, & Abbott, 2005), which allow for the simultaneous estimation of separate but correlated continuous and categorical LGC models. Two-part models were selected because the non-normal outcome data were caused by a substantial number of participants reporting absence of the outcome variable (i.e., no delinquent activities or drug use). In two-part models, the original distribution of the outcome is separated into categorical and continuous parts, each modeled by separate but correlated growth functions. In the categorical part of the model, a binary indicator variable is created to indicate any vs. none of the outcome in question. The continuous part models the frequency of occurrence of the outcome, given that the outcome had taken place (i.e., number of days of substance use for those who used substances at all). Effect size estimates using Cohen’s d coefficient were calculated for condition effects (i.e., when comparing change in UC-FT versus UC-Other) for main clinical outcomes based on Feingold’s (2009) procedures for growth modeling analyses.

Results

Treatment Attendance

Of the 205 participants 157 (77%) attended at least one treatment session at the assigned site, including 74% of UC-FT cases and 79% of UC-Other cases. The mean number of sessions for each case across the sample was 8.5 (SD = 9.8). Contrary to hypothesis, study conditions did not differ significantly on mean number of sessions attended: UC-FT averaged 8.7 sessions (SD = 9.8) attended, and UC-Other averaged 8.3 sessions (SD = 9.9; t(155) = −.21, p = .84). These rates are comparable to treatment engagement and attendance rates broadly reported for child mental health services (Garland et al., 2013).

Treatment Outcomes: Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics for all outcome variables at each timepoint are presented in Table 2 separately for UC-FT and UC-Other. Distributions for delinquency and substance use showed significant departures from normality, hence our use of two-part LGC models (described above).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) for primary outcome variables by treatment condition

| UC-FT | UC-Other | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| BL | 3-mo | 6-mo | 12-mo | BL | 3-mo | 6-mo | 12-mo | |

|

|

||||||||

| Adol-reported externalizing | 16.0 (9.6) | 13.8 (10.3) | 12.5 (10.2) | 10.7 (8.4) | 15.8 (8.8) | 12.8 (9.1) | 12.6 (8.2) | 11.9 (9.2) |

| Adol-reported internalizing | 14.2 (9.7) | 13.1 (12.0) | 11.1 (10.1) | 9.4 (8.9) | 13.0 (8.3) | 10.6 (7.6) | 10.2 (8.3) | 10.0 (8.4) |

| Caregiver-reported externalizing | 18.2 (12.0) | 16.1 (13.9) | 13.0 (10.5) | 14.3 (12.8) | 18.1 (11.1) | 16.3 (13.0) | 14.6 (10.6) | 13.5 (12.1) |

| Caregiver-reported internalizing | 13.3 (7.9) | 11.2 (8.7) | 10.3 (8.4) | 11.1 (11.0) | 12.4 (8.5) | 10.6 (8.7) | 9.9 (8.3) | 8.8 (8.4) |

| Number of delinquent acts | 3.6 (3.1) | 3.5 (2.5) | 2.3 (1.7) | 2.5 (2.5) | 3.9 (2.8) | 3.1 (2.6) | 3.0 (2.1) | 2.7 (2.6) |

| AOD daysa | 6.6 (8.5) | 8.9 (9.9) | 6.4 (7.9) | 5.5 (7.5) | 6.2 (9.2) | 6.8 (8.7) | 8.4 (10.6) | 7.9 (10.5) |

Note.

Data on AOD days was assessed at each month, using the Timeline Follow Back Method. However, for purposes of calculating descriptive statistics, monthly data were compressed to fit the timetable of the other primary outcome measures. Thus, AOD days reported at baseline = average days of use per month in the three months prior to baseline; AOD days reported at 3-month follow up = average days of use per month in months 1–3 post-baseline; AOD days reported at 6-month follow up = average days of use per month in months 4–6 post-baseline; AOD days reported at 12-month follow up = average days of use in months 7–12 post-baseline.

Externalizing and Internalizing Symptoms

Likelihood ratio difference tests determined that quadratic models produced the best fit to the data for caregiver-reported externalizing, adolescent-reported internalizing, and caregiver-reported internalizing symptoms. For adolescent-reported externalizing, the difference test favored the linear model. However, given that the linear and quadratic models produced equivalent findings for adolescent-reported externalizing, quadratic models are presented for all externalizing and internalizing outcomes to maintain consistency.

As mentioned, we first tested unconditional models for all outcomes to obtain the unadjusted growth factors. Significant linear declines in symptoms were found for adolescent-reported externalizing (pseudo z = −3.6, p < .001) and internalizing (pseudo z = −5.6, p < .001), and likewise, for caregiver-reported externalizing (pseudo z = −5.0, p < .001) and internalizing (pseudo z = −4.5, p < .001). Additionally, significant quadratic change was found for caregiver-reported externalizing (pseudo z = 2.4, p < .05), adolescent-reported internalizing (pseudo z = 2.2, p < .05), and caregiver-reported internalizing (pseudo z = 2.5, p < .05), and trend-level quadratic change was found for adolescent-reported externalizing (pseudo z = .21, p < .10), such that initial decreases were followed by a leveling off (i.e., plateau) of symptoms. Taken together, the unconditional models revealed significant overall declines in externalizing and internalizing symptoms across the study period for the entire sample.

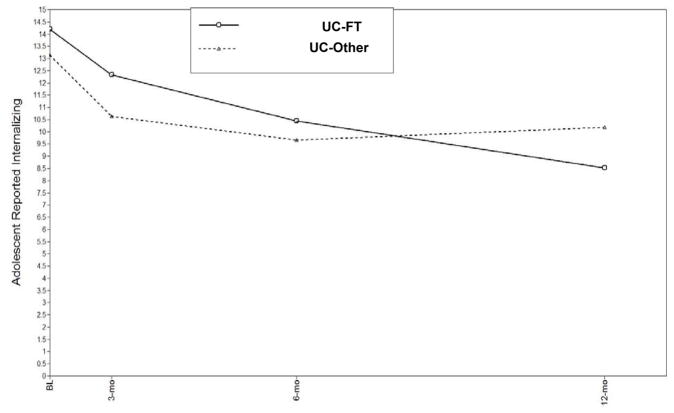

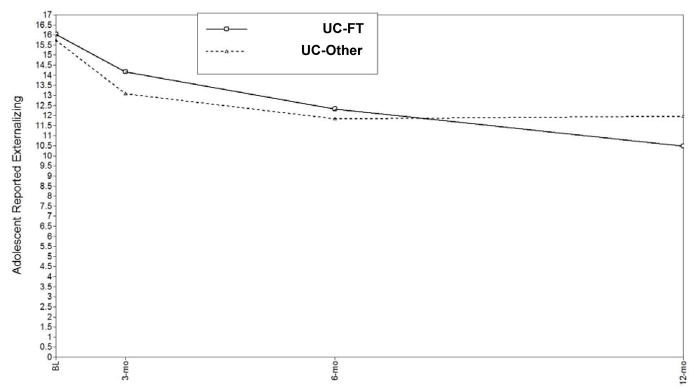

Following the unconditional models, we tested models including study condition, study track, and demographic covariates. Initial models included condition by track interactions; however, because no significant interactions were found for externalizing and internalizing symptoms, we present results from the main effect models. No main effects of study track on externalizing or internalizing were found. Significant condition effects were found for adolescent-reported externalizing (pseudo z = −2.3, p < .05, d = .68) and adolescent-reported internalizing (pseudo z = −3.3, p < .01, d = .78), indicating greater declines in externalizing and internalizing symptoms over time for adolescents in the UC-FT condition. Model-estimated mean trajectories are shown in Figure 2 for adolescent-reported externalizing behavior and in Figure 3 for adolescent-reported internalizing behavior; these figures indicate that UC-FT youth maintained continuous declines in these symptoms over the course of one year, whereas declines among UC-Other youth leveled off or slightly reversed over time.

Figure 2.

Estimated mean trajectories for adolescent-reported externalizing behavior, comparing study conditions across follow-up assessment points.

Figure 3.

Estimated mean trajectories for adolescent-reported internalizing behavior, comparing study conditions across follow-up assessment points.

Delinquency

Given the propensity of zeroes present in the delinquency outcome variable, a two-part growth model was used to examine change over time and condition effects. Likelihood ratio difference tests revealed that a linear model provided the best fit to the data. The unconditional model demonstrated significant overall declines over time in both the proportion of the sample engaging in delinquency (pseudo z = −8.1, p < .001) and in the number of delinquent activities (pseudo z = −11.5, p < .001). After testing the unconditional model, we tested the full model including study condition, track, demographic covariates, and condition by track interaction. A significant condition by track interaction was found predicting change over time in number of delinquent activities (pseudo z = −3.9, p < .001); based on this finding, condition effects were tested and interpreted separately within each track.

For clients in the MH track, overall significant declines were found in both proportion engaging in delinquency (pseudo z = −5.3, p < .001) and number of delinquent acts (pseudo z = −6.1, p < .001). However, no significant condition effects were found. For clients in the SU track, similar overall declines were found in proportion engaging in delinquency (pseudo z = −5.9, p < .001) and number of delinquent acts (pseudo z = −6.2, p < .001). For the SU track there was also a significant condition effect for number of delinquent acts (pseudo z = −4.9, p < .001, d = .26), suggesting that SU track adolescents who received UC-FT showed greater decreases in delinquency compared to those who received UC-Other.

Substance Use

A two-part growth model was also used for the substance use outcome due to the pile-up of zeroes. The likelihood ratio difference test indicated that the quadratic model provided a somewhat better fit to the data than the linear model. However, due to concerns about model non-convergence and to maintain consistency with the delinquency models, we present linear models. Because the substance use outcome was most relevant to the SU track, we made the a priori decision to examine change over time and condition effects for the full sample and then separately for SU track adolescents. Given this decision, we did not include study track or condition by track interactions in the full sample model.

In the full sample, no significant overall change was found in the proportion of adolescents using alcohol or drugs or in the amount of alcohol or drugs used. Additionally, no significant condition effects were found. When analyses were limited to those in the SU track, no overall change was found in the proportion using substances or the amount of substances used. However, a significant condition effect favoring UC-FT was found for both proportion of the sample using substances (pseudo z = −3.6, p < .001, OR = 1.8) and amount of substances used (pseudo z = −4.3, p < .001, d = .13). Overall, these data indicate that for adolescents in the SU track, UC-FT produced greater declines in substance use than UC-Other.

Clinical Significance

To examine the clinical significance of symptom reduction, we examined within-condition change from baseline to 12-month follow-up in the percentage of adolescents reporting no delinquent acts in the prior month (entire sample) and those reporting complete abstinence from alcohol and drugs in the prior 3 months (SU track clients only). Within UC-FT, 19% reported no delinquency at baseline, and this increased to 50% at 12-month follow-up. Within UC-Other, 18% reported no delinquency at baseline, and this increased to 45% at follow-up. Abstinence rates increased from 0% at baseline to 40% at one year in UC-FT and from 0% at baseline to 26% at one year in UC-Other. There was also improvement across study condition in diagnostic rates: 47% who had ODD at study entry no longer met criteria at one year [χ2(1) = 6.3, p < .05]; 39% no longer met CD criteria [χ2(1) = 2.6, ns]; and 19% no longer met SUD criteria [χ2(1) = 16.7, p < .001]. No between-condition differences in diagnostic change were found.

Discussion

This study found that adolescents randomly assigned to either non-manualized family therapy or alternative usual care in outpatient settings made substantial improvements in multiple problem areas at one-year follow-up. Across the entire sample, which included both mental health and substance use referrals in both treatment conditions, adolescents showed significant declines in youth-reported externalizing and internalizing symptoms, caregiver-reported externalizing and internalizing symptoms, and delinquent activities. In addition, UC-FT produced greater reductions than UC-Other in youth-reported externalizing and internalizing symptoms among the whole sample, in delinquency acts among substance-using youth, and in alcohol and drug use among substance-using youth. The trajectories of youth-reported externalizing and internalizing symptoms indicated that UC-FT youth maintained continuous declines over the course of one year, whereas declines among UC-Other youth leveled off or slightly reversed over time.

Interpreting the Results for Family Therapy

These results support the effectiveness of the FT approach for treating ABPs in usual care. Non-manualized FT had measurable success in treating conduct and substance use problems in an everyday clinical setting: For the 10 client outcomes that showed significant change at one-year follow-up (out of 12 total), UC-FT was superior to UC-Other on five outcomes and equivalent on the other five. It is noteworthy that the treatment effect sizes by which UC-FT outperformed UC-Other on those five outcomes were mostly in the small-to-moderate range, which is consistent with effect sizes for manualized FT derived in recent meta-analyses. For example Baldwin and colleagues (2012) analyzed 24 randomized trials that included various manualized FT models and found that across conduct and drug problems combined, FT was superior to TAU with a mean effect size d = .21, and superior to competing evidence-based treatments with a mean effect size d = .26. Tanner-Smith and colleagues (2012) reviewed a wide variety of treatments for adolescent drug abuse and found that only manualized FT demonstrated consistently significant effect sizes in comparison to other approaches, with an overall mean effect size of d = .26 versus all other treatments, including an effect size of d = .09 versus TAU specifically (representing four comparisons only). Current findings are consistent with the well-supported assertion that FT is especially beneficial for drug-using teens (see AUTHOR, in press a; Tanner-Smith et al., 2012). Among the subsample of substance users, UC-FT was more effective than UC-Other in curbing delinquency as measured by problem severity (number of acts) and in curbing substance use as measured by either problem severity (number of days of use) or abstinence (any use versus no use). Based on these data, albeit from one study only, structural-strategic FT in routine care produced effects in line with those of manualized FT reported in controlled trials.

Contrary to hypothesis, UC-FT was not superior in retention of clients in treatment. Both efficacy and effectiveness trials of manualized FT (e.g., Robbins et al., 2011) regularly find that FT surpasses alternative treatments and TAU in treatment engagement. The failure of UC-FT to outperform UC-Other in this study may be due in large part to the researcher’s use of intensive linkage procedures to facilitate completion of the first intake session by all participants. Such procedures represent a drastic change from typical practice, so that the sample was definitively not “referral as usual”. By leveling the playing field to ensure equivalent linkage rates across sites, the study design may have undercut the broader treatment engagement advantages traditionally enjoyed by manualized FT. Another contributing factor is that, unlike manualized FT models, the UC-FT site did not feature a standardized set of family engagement interventions designed to bolster attendance (though UC-FT therapists may well have implemented non-manualized engagement interventions of some kind). Also, the UC-FT stipulation that parents attend most sessions may have activated logistical barriers that impacted parents but not teens (e.g., child care, work or other scheduling conflicts). Teens in both conditions could readily attend sessions alone using the extensive public transportation system.

The validity of study results is bolstered by fidelity data supporting the credibility of the UC-FT condition as a bona fide representative of the FT approach. Note that UC-FT therapists held office-based sessions exclusively, which is consistent with UC practice as well as with numerous studies of office-based manualized FT models (e.g., Liddle et al., 2008; Waldron et al., 2001). Yet several studies have tested FT models that prescribe frequent home visits (e.g., Henggeler et al., 2002; Robbins et al., 2008), and large-scale FT dissemination efforts typically feature home-based sessions and case management activities in their implementation guidelines, especially when targeting juvenile justice populations (Henggeler & Sheidow, 2012). It remains to be determined whether, how much, and for whom home-based interventions are required to effectively treat ABPs.

Interpreting the Results for Non-Family Treatments

Results complement the growing roster of studies in which TAU performed with merit in comparison to manualized EBIs. In the current study, UC-Other effects were indistinguishable from UC-FT for parent-reported symptomatology; for adolescent-reported symptoms other than substance use, UC-Other showed gains over time that were simply outpaced by UC-FT. One commonality among recent studies with favorable TAU results (e.g., Robbins et al., 2011; Southam-Gerow et al., 2010; Weisz et al., 2009) is that agency therapists were randomly assigned to study condition, which effectively eliminates numerous provider-centered biases that may have worked against TAU in other studies. Of course therapist randomization was neither feasible nor desirable in the current study, given its fully naturalistic design. It is worth pointing out that observational data collected on UC-Other indicates that these therapists received EBI utilization scores that fell between Not at all and A little bit for both MI/CBT and FT techniques. A face-value interpretation of these data is that UC-Other featured negligible levels of EBIs. However, this interpretation is mitigated by several considerations: (a) Despite multidimensional fidelity data supporting its credibility in delivering bona fide FT, the UC-FT condition received an observer rating that barely reached the anchor value for A little bit; (b) As noted in the Results section, there are important caveats to face-value interpretations of averaged scores for EBI fidelity ratings; (c) It may be unfair to hold UC-Other therapists to standards they did not hold for themselves: They did not proclaim unified allegiance to any particular approach, leaving open the possibility that observers were using an improper or poorly calibrated assessment tool.

Overall, the solid performance of TAU in many effectiveness studies raises intriguing questions about treatment processes in UC that may be best addressed with well-calibrated observational methods (Weingardt & Gifford, 2007): Does TAU get results by utilizing adapted versions or portions of EBIs? Via “common factors” such as therapeutic alliance? Placebo effects coupled with client self-change processes? While it is possible that most TAU contains little or no EBIs (e.g., Hurlburt et al., 2010; Santa Ana et al., 2008), that remains to be (literally) seen as this research area advances. Taking a different tack, Weisz and colleagues (2013a) argue that EBIs have underperformed in controlled comparisons with TAU due to the numerous child, family, practitioner, and treatment context variables prevalent in the mental health ecosystem (e.g., comorbidity, family stress, competing demands on therapists) that mute the potency of manualized EBIs delivered in naturalistic conditions. Their meta-analysis examining this issue (Weisz et al., 2013b) found that EBIs were not superior to TAU for clinically referred youth or youth with psychiatric diagnoses. In the current study, the FT approach did promote gains among clinically complex cases in a natural setting.

Study Strengths, Limitations, and Alternative Interpretations

A main strength of the study was high ecological validity that affirms the generalizability of findings to real-world practice: Community therapists operated in everyday settings without extramural support, and adolescents from diverse backgrounds presented an array of clinical disorders, with comorbidity being the norm. Because most referrals came from school contacts, and research staff helped link clients to initial intakes, the sample may differ in important ways from typical clinic referral streams. Randomization strengthened internal validity and helped control for unmeasured influences that might confound results, and intent-to-treat analyses were used. Both adolescent and caregiver reports were used to gauge clinical progress. Assessment of organizational culture and climate indicated that these workplace characteristics were broadly representative of national UC norms, and that study conditions were equivalent on the whole, though within TAU there were not enough therapists per site to reliably assess individual clinics.

The main limitation was that only one site practiced FT, making it impossible to fully separate condition effects from site effects or to make firm assertions about FT effectiveness across the broader landscape of FT practices in UC. Certainly the UC-FT site cannot be considered an “early adopter” of manualized EBIs; it is more accurate to label it a holdover from earlier decades in which the structural-strategic FT approach flourished during the child guidance movement in community mental health. Moreover the site, which operated in business-as-usual fashion and was embedded in the same geographic and economic context as the UC-Other sites, had no obvious features that made it exceptional or singular, other than allegiance to the FT approach. For this reason we did not pursue cost-benefit analyses, as there appeared to be no basis for a meaningful margin of difference in operational costs between UC-FT and its peer UC-Other clinics, especially those clinics that were also CMHCs, and no apparent costs (or cost savings) related to providing FT as the standard of care. Finally, because the profile of organizational characteristics was equivalent across conditions, these characteristics do not present a compelling alternative explanation for the condition effects found in this study, and due to insufficient variability they were not included as covariates in analyses of clinical outcomes.

There were several other important limitations as well. The number of participating sites was too small to control for site clustering effects via random-effects analyses. The study was not adequately powered to support post-hoc inspection of individual site effects using similarly rigorous analyses; thus it is not known whether one or two UC-Other sites performed at a significantly higher or lower level than the others. Participating therapists at each site were self-selected, constituted a minority of available clinical staff, and may not have been representative of all staff at the given site. Because UC-FT and UC-Other produced equivalent gains for the only two outcomes measured via caregiver report, there is no direct evidence that FT was superior to alternative care in the eyes of the primary guardians. Because all families received research-supported intensive linking procedures, study findings may not be fully generalizable to the usual referral streams that feed study sites. Absent a no-treatment control group, the magnitude of research assessment effects and treatment referral effects on client outcome cannot be estimated, although such effects are presumed equally prevalent across conditions. Due to space constraints, investigation of predictors of treatment attendance, dose-response effects, and fidelity-outcome effects will be pursued in future studies. Finally, because therapists were not randomly assigned to condition, we cannot rule out that UC-FT therapists were more effectual than their UC-Other counterparts on some outcomes for reasons outside their clinical approach, for example: the particular site, and/or the FT discipline as a whole, attracts better-than-average clinicians; the UC-FT therapists were more committed to evidence-based practice in general, such that observed between-condition differences can be attributed to general EBI zeal rather than FT effectiveness per se; or others.

Clinical and Policy Implications

The UC-FT therapists in this study trained in social work and family therapy graduate programs, and they were employed in a CMHC that provided FT as routine care. That these mainstream working conditions can yield measurable successes in FT fidelity and especially clinical outcomes presents a strong argument for growing the availability of family-based services in behavioral healthcare. Although allegiance to the FT orientation remains common among therapists and specialty services located in youth treatment settings (Hoagwood, 2005), it is not known how much, and with what fidelity, family therapy interventions are actually utilized in everyday practice. Study results encourage practitioners to deliver bona fide FT interventions for ABP youth, and perhaps encourage agencies to prioritize support for the FT approach in clinics serving this population in large numbers (see Barth, Kolivoski, Lindsey, Lee, & Collins, in press). That said, there were also positive results for the collection of UC clinics that provided non-family treatment, a constructive finding for the adolescent behavioral healthcare system as a whole and for the vast numbers of high-risk teenagers with unmet treatment needs.

Study results may also impact the cost-benefit analyses undertaken by governing agencies that set regulatory policies and system-wide priorities for treating ABP youth. The resounding success of manualized FT is a powerful recommendation for initiating contracted services with an available purveyor. But for providers and systems experiencing resource scarcity, it may be legitimate to weigh the feasibility of cultivating “homegrown” FT services—perhaps factoring in upgrades to local supervision and quality monitoring procedures (AUTHOR, 2013a)—against the barriers of importing a manualized model. That said, the current study did not directly test naturalistic FT against manualized FT, and there is no legitimate basis for claiming that naturalistic FT can be as consistently effective as purveyor-driven versions have proven. Moreover, arguably the fundamental question—How many and what kinds of QA procedures are needed to produce strong fidelity and client outcomes?—remains to be addressed.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA019607). The authors would like acknowledge the dedicated work of the CASALEAP research staff: Cynthia Arnao, Daniela Caraballo, Benjamin Goldman, Diana Graizbord, Jacqueline Horan, Emily McSpadden, Catlin Rideout, Jeremy Sorgen, and Gabi Spiewak. We are grateful to the study sites for their generous cooperation, with special thanks to the Roberto Clemente Center.

Contributor Information

Aaron Hogue, Email: athogue@aol.com, The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, New York, NY.

Sarah Dauber, Email: sdauber@casacolumbia.org, The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, New York, NY.

Craig E. Henderson, Email: craightml@sbcglobal.net, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TX

Molly Bobek, Email: mbobek@casacolumbia.org, The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, New York, NY.

Candace Johnson, Email: cjohnson@casacolumbia.org, The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, New York, NY.

Emily Lichvar, Email: elichvar@casacolumbia.org, The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, New York, NY.

Jon Morgenstern, Email: jmorgens@casacolumbia.org, The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, New York, NY.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. ASEBA School Age Forms and Profiles. Burlington, Vt: ASEBA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: APA; 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- American Society on Addiction Medicine. ASAM patient placement criteria for the treatment of substance related disorders. 2. Chevy Chase; MD: 2001. revised ed. [Google Scholar]

- AUTHOR. Assessing fidelity to evidence-based practices in usual care: The example of family therapy for adolescent behavior problems. Evaluation and Program Planning. 2013b;37:21–30. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AUTHOR. Therapist self-report of evidence-based practices in usual care for adolescent behavior problems: Factor and construct validity. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0442-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AUTHOR. Reliability of therapist self-report on treatment targets and focus in family-based intervention. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2013c doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0520-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AUTHOR. Validity of therapist self-report ratings of fidelity to evidence-based practices for adolescent behavior problems: Correspondence between therapists and observers. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. doi: 10.1007/s10488-014-0548-2. in press b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AUTHOR. Treatment techniques and outcomes in multidimensional family therapy for adolescent behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:535–543. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.4.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AUTHOR. Evidence base on outpatient behavioral treatments for adolescent substance use: Updates and recommendations 2007–2013. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2014.915550. in press a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AUTHOR. Family-based treatment for adolescent substance abuse: Controlled trials and new horizons in services research. Journal of Family Therapy. 2009;31:126–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6427.2009.00459.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AUTHOR. Making fidelity an intramural game: Localizing quality assurance procedures to promote sustainability of evidence-based practices in usual care. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2013a;20:60–77. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin SA, Christian S, Berkeljon A, Shadish W, Bean R. The effects of family therapies for adolescent delinquency and substance abuse: A meta-analysis. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2012;38:281–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth RP, Kolivoski KM, Lindsey MA, Lee BR, Collins KS. Translating the common elements approach: Social work’s experiences in education, practice, and research. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.848771. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Catalano RF, Fleming CB, Haggerty KP, Abbott RD. Adolescent substance use outcomes in the Raising Healthy Children project: A two-part latent growth curve analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:699–710. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Nich C, Martino S, Frankforter TL, Farentinos C, et al. Motivational interviewing to improve treatment engagement and outcome in individuals seeking treatment for substance abuse: A multisite effectiveness study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;81:301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers D, Ringeisen H, Hickman E. Federal, state, and foundation initiatives around evidence-based practices for child and adolescent mental health. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2005;14:307–327. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita B, Daleiden E, Ebesutani C, Young J, Becker K, Starace N. Evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: An updated review of indicators of efficacy and effectiveness. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2011;18:154–172. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, Weisz JR. Modularity in the design and application of therapeutic interventions. Applied & Preventive Psychology. 2005;11:141–156. [Google Scholar]

- Cook JM, Biyanova T, Elhai J, Schnurr PP, Coyne JC. What do psychotherapists really do in practice? An internet study of over 2,000 practitioners. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2010;47:260–267. doi: 10.1037/a0019788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deming WE. Out of the crisis. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Diggle P, Heagerty P, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data. 2. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Strycker AL, Li F, Alpert A. An introduction to latent variable growth curve modeling. Mahwah, NJ: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Huizinga D, Ageton SS. Explaining delinquency and drug use. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Embry DD, Biglan A. Evidence-based kernels: Fundamental units of behavioral influence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2008;11:75–113. doi: 10.1007/s10567-008-0036-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feingold A. Effect sizes for growth-modeling analysis for controlled clinical trials in the same metric as for classical analysis. Psychological Methods. 2009;14:43–53. doi: 10.1037/a0014699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo KP, Barlow DH. Factors involved in clinician adoption and nonadoption of evidence-based interventions in mental health. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2012;19:93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Bickman L, Chorpita BF. Change what? Identifying quality improvement targets by investigating usual mental health care. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;37:15–26. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0279-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Haine-Schlagel R, Brookman-Frazee L, Baker-Ericzen M, Trask E, Fawley-King K. Improving community-based mental health care for children: Translating knowledge into action. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2013;40:6–22. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0450-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford EV, Tavakoli S, Weingardt KR, Finney JW, Pierson HM, et al. How do components of evidence-based psychological treatment cluster in practice?: A survey and cluster analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2012;42:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Green P. The effects of organizational culture and climate on the access to mental health care in child welfare and juvenile justice systems. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2005;33:433–448. doi: 10.1007/s10488-005-0016-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley J. Problem-solving therapy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Clingempeel W, Brondino MJ, Pickrel SG. Four-year follow-up of multisystemic therapy with substance-abusing and -dependent juvenile offenders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2002;41:868–874. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler SW, Sheidow AJ. Empirically supported family-based treatments for conduct disorder and delinquency in adolescents. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2012;38:30–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00244.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood K. Family-based services in children’s mental health: A research review and synthesis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:690–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlburt MS, Garland AF, Nguyen K, Brookman-Frazee L. Child and family therapy process: Concordance of therapist and observational perspectives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;37:230–244. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0251-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaslow NJ, Broth MR, Smith CO, Collins MH. Family-based interventions for child and adolescent disorders. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2012;38:82–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddle HA, Dakof GA, Turner RM, Henderson CE, Greenbaum PE. Treating adolescent drug abuse: A randomized trial comparing multidimensional family therapy and cognitive-behavior therapy. Addiction. 2008;103:1660–1670. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh R, Barlow DH. The dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychological treatment: A review of current efforts. American Psychologist. 2010;65:73–84. doi: 10.1037/a0018121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh R, Murray H, Barlow DH. Balancing fidelity and adaptation in the dissemination of empirically supported treatments: The promise of transdiagnostic interventions. Behavior Research and Therapy. 2009;47:946–953. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Bannon WM. Engaging families in child mental health services. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2004;13:905–921. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Tonigan JS. Motivational interviewing in drug abuse services: A randomized trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:754–763. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minuchin S, Fishman HC. Family therapy techniques. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Blanchard KA, Morgan TJ, Labouvie E, Hiyaki J. Testing the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral treatment for substance abuse in a community setting: Within treatment and posttreatment findings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:1007–1017. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.6.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen B, Muthen L. Mplus User’s Guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins MS, Feaster D, Horigian V, Rohrbaugh M, et al. Brief strategic family therapy versus treatment as usual: Results of a multisite randomized trial for substance-using adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:713–727. doi: 10.1037/a0025477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins MS, Szapocznik J, Dillon FR, Turner CW, Mitrani VB, Feaster DJ. The efficacy of structural ecosystems therapy with drug-abusing African American and Hispanic American adolescents. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:51–61. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe CL. Family therapy for drug abuse: review and updates 2003–2010. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2012;38:59–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2011.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santa Ana EJ, Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Frankforter TL, Carroll KM. What is usual about “treatment-as-usual”? Data from two multisite effectiveness trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35:369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Sheidow A, Chapman J. Clinical supervision in treatment transport: Effects on adherence and outcomes. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:410–421. doi: 10.1037/a0013788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Dunbar GC. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59:22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Molina BS, Gnagy EM, Waschbusch DA, Biswas A, Karch KM. The delinquency outcomes of boys with ADHD with and without comorbidity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:21–32. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9443-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Followback user’s guide: A calendar method for assessing alcohol & drug use. Toronto, Canada: Addiction Research Foundation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Southam-Gerow M, Weisz J, Chu B, McLeod B, Gordis E, Connor-Smith J. Does cognitive behavioral therapy for youth anxiety outperform usual care in community clinics? An initial effectiveness test. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2010;49:1043–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices (NREPP). Intervention summaries: Multisystemic Therapy for Juvenile Offenders, Brief Strategic Family Therapy, & Multidimensional Family Therapy. Rockville, MD: Govt. Printing Office (SAMHSA); 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner-Smith EE, Wilson SJ, Lipsey MW. The comparative effectiveness of outpatient treatment for adolescent substance abuse: A meta-analysis. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2012;44:145–158. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron HB, Slesnick N, Brody JL, Turner CW, Peterson TR. Treatment outcomes for adolescent substance abuse at 4- and 7-month assessments. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2001;69:802–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]