Abstract

Public debate on same-sex marriage often focuses on the disadvantages that children raised by same-sex couples may face. On one hand, little evidence suggests any difference in the outcomes of children raised by same-sex parents and different-sex parents. On the other hand, most studies are limited by problems of sample selection and size, and few directly measure the parenting practices thought to influence child development. This research note demonstrates how the 2003–2013 American Time Use Survey (n = 44,188) may help to address these limitations. Two-tier Cragg’s Tobit alternative models estimated the amount of time that parents in different-sex and same-sex couples engaged in child-focused time. Women in same-sex couples were more likely than either women or men in different-sex couples to spend such time with children. Overall, women (regardless of the gender of their partners) and men coupled with other men spent significantly more time with children than men coupled with women, conditional on spending any child-focused time. These results support prior research that different-sex couples do not invest in children at appreciably different levels than same-sex couples. We highlight the potential for existing nationally representative data sets to provide preliminary insights into the developmental experiences of children in nontraditional families.

Keywords: Parenting, Family structure, LGBT, Time use, Gender

Introduction and Background

The public debate on same-sex marriage has frequently focused on the potential impact of these unions on children (Cole et al. 2012; Joslin 2011). Simply put, opponents of same-sex marriage argue that heterosexual unions provide inherently better contexts for positive child development than same-sex unions (Garrett and Lantos 2013). Little research exists, however, to support this argument, with the majority of studies finding little to no effects for children living in same-sex families (Biblarz and Stacey 2010; Crouch et al. 2014; Gartrell and Bos 2010; Rivers et al. 2008; Wainright et al. 2004).

Several limitations have diluted the power of this “no difference” evidence base, and those limitations need to be better addressed moving forward. First, because many studies of same-sex families rely on convenience samples, their findings are not generalizable and may overrepresent families with characteristics that are confounded with other factors related to better child outcomes (Biblarz and Stacey 2010; Gartrell and Bos 2010). Second, same-sex families may be more selective than other families because their children are more likely to come from adoption (often from foster care), from artificial insemination, or through divorce from an opposite-sex partner and subsequent partnership with a new stepparent (Lavner et al. 2012; Potter 2012; Rosenfeld 2010). Third, quantitative research on child outcomes in same-sex families makes assumptions about the types of parenting investments made in different- and same-sex families without directly testing these assumptions, often because the data do not allow for the study of parenting (Biblarz and Stacey 2010; Gartrell and Bos 2010; Rivers et al. 2008; Wainright et al. 2004).

This parenting angle deserves further consideration, especially with data that can address many of the other limitations we noted earlier. Research has documented the benefits for children (above and beyond selection effects) of living with two parents rather than in a single-parent home, with parental time investment being an important mechanism of influence (Crosnoe and Cavanagh 2010; McLanahan 2004; Sandberg and Hofferth 2001). What we do not know is whether this pattern extends to same-sex couples relative to different-sex couples. The former have two parents, but are two parents of the same sex different from two parents of the opposite sex? Past research with convenience or otherwise nonrepresentative samples has not found many differences in parenting associated with the gender composition of two-parent families (Biblarz and Stacey 2010; Farr et al. 2010). Investigating whether this pattern extends to parental time investment in a representative sample can inform this general conclusion.

Exploring time engaged in child-focused activities with household children across same- and different-sex partnerships is an important step in understanding whether and how the gender composition of two-parent families matters. This research note provides a preliminary description of data relevant to this issue from the American Time Use Survey (ATUS), which, we argue, is a valuable source for demographers interested in studying family structure in a time of rapid change in how families are defined. The ATUS captures how and with whom people spend their time in a given day, with a long line of social science research underscoring time spent with children as a developmentally important marker of parenting investments (e.g., Bianchi 2011; Kalil et al. 2012). Nevertheless, one major weakness is the relatively small sample of parents in same-sex partnerships. In this sample, 55 parents were identified as having same-sex partners; hence, the findings should be interpreted with some caution.

Method

The ATUS is a nationally representative time-diary survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. One member of each household sampled was asked to fill out a time diary, reporting detailed information on the activities they participated in, and with whom, over a 24-hour period. In addition, sociodemographic information on the respondent and other household members was collected. We pooled 11 years of data (2003–2013) and then limited this sample to respondents who had a spouse or partner living with them, and household children aged 18 years or younger (n = 44,188). Although the legislation concerning same-sex marriage in many states underwent major changes during this period, we use every ATUS year available to maximize the sample size in order to allow for comparisons across gender. We also controlled for year of study participation in the multivariate analyses.

Measures

Time Use

Total time engaged with children was a continuous measure of minutes respondents reported spending doing child-focused activities with household children (e.g., physical care, playing, teaching) or on activities directly related to parenting investment (e.g., attending children’s events, participating in parent-teacher conferences, organizing or planning activities). Table 3 in the appendix provides a list of these activities. Total time engaged with children was then used to create another measure of time: the percentage of nonwork time engaged with children (i.e., the proportion of time engaged with children as a proportion of all time not spent at or commuting to paid employment). Using this metric, the proportion of nonwork time engaged with children could be seen as a measure of the free time potentially available for parents to make decisions about investing that time in their children.

Family Structure

Respondents identified the sex of and their relationship to each household member. From this information, we identified different- and same-sex couples based on whether the respondent identified either a spouse or unmarried partner and the sex of that partner. Four dummy variables indicated respondents’ and their partners’ sex: (1) women with different-sex partners (n = 23,507), (2) women with same-sex partners (n = 38), (3) men with different-sex partners (n = 20,626), and (4) men with same-sex partners (n = 17). Although these data provided a unique opportunity to explore time use among same-sex families, a limitation of this survey—and with most other nationally representative data sets in the United States—is that respondents were not explicitly asked whether their partner is of the same or different sex or about their sexual identity.

Covariates

We created controls for other factors that could have influenced the time parents engaged with children (employment, partner’s employment, educational attainment, partner’s education, family income, number of children in the household, age of children, gender of children, respondent race/ethnicity, nativity, age, whether they were a student, geographic region, and whether they lived in a metropolitan area) and time-diary information (whether the diary was recorded on a weekend or a summer month, the year, and whether it was a holiday). Table 4 in the appendix presents a description of some of these key covariates by family structure. Overall, those in same-sex partnerships were more socioeconomically and demographically advantaged (e.g., income, education) than those in different-sex partnerships, highlighting the importance of these controls for the multivariate analyses.

Analytical Plan

After estimating bivariate associations between family structure and time engaged with children, we turned to a multivariate framework that controlled for other variables potentially confounded with parenting and family structure. We fit the data using a two-tier Cragg’s Tobit alternative (Cragg 1971). This technique, which allows for the joint estimation of two separate processes, is often used to analyze time-diary data because they usually contain many 0 values for certain activities. This “double hurdle” approach is a particularly appropriate estimation technique given the proportion of parents who report not spending child-focused time with their children in a 24-hour period (a little more than one-third of the sample) and given that this may not be a true reflection of parents’ long-run time engaged in child-focused activities (i.e., 0 values are likely anomalies resulting from the small window of time recorded, with most parents helping bathe or play with their children, for example, during a given week) (Stewart 2009).

For this study, the first estimate was the probability that parents spent any time engaged with children, and the second was the amount of time engaged with children based on that condition. These two tiers provided insight into not only family structure differences in time engaged with children but also the potential selection factors influencing that time. In Stata, the craggit procedure estimated these models (Burke 2009), with the suite of mi commands used to impute for three covariates with missing values—family income (7.8 % of all values), partner’s education (2.3 %), and metropolitan area (0.6 %)—by estimating and averaging 100 imputations. Weighting accounted for the complex survey design.

Results

Table 1 presents the bivariate associations between family structure and time engaged with children. Overall, women in same-sex partnerships spent the most time engaged with children (an average of 111 minutes per day), but this amount did not differ significantly from those for women in different-sex partnerships (99 minutes per day) and men in same-sex partnerships (103 minutes). Men with different-sex partners spent the least amount of time engaged with children than all other groups, averaging 51 minutes per day. Examining the proportion of time parents engaged with children as a proportion of time not committed to work revealed similar findings.

Table 1.

Bivariate associations between family structure and time engaged children

| N | Reported Spending Any Time With Children | Minutes With Children | % Nonwork Time With Children | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| N | % | Total | Conditional | Total | Conditional | ||

| Women With Different-Sex Partners | 23,507 | 17,479 | 74.06 (43.83) | 99.25c (120.39) | 134.02c (119.18) | 7.64c (8.84) | 10.75c (9.15) |

| Women With Same-Sex Partners | 38 | 32 | 88.40c (32.45) | 111.36c (119.18) | 125.97 (119.38) | 9.20c (9.15) | 10.81 (9.01) |

| Men With Different-Sex Partners | 20,626 | 11,289 | 52.53a,b,c (49.94) | 51.04a,b,c (89.96) | 97.16a (104.53) | 4.42a,b (7.29) | 8.96a (8.18) |

| Men With Same-Sex Partners | 17 | 14 | 82.8c (38.90) | 103.94c (124.97) | 125.53 (127.28) | 7.90 (8.96) | 11.09 (8.75) |

| Total | 44,188 | 28,814 | 63.35 (48.19) | 75.25 (109.03) | 118.78 (116.59) | 6.04 (8.26) | 10.02 (8.57) |

Notes: Unweighted ns, weighted %/Means. Standard deviations are shown in parentheses. Chi-squared and t tests showed no significant differences from male with male partner in the bivariate associations; significance indicators for other comparisons are as follows:

Different from female with male partner at p < .05.

Different from female with female partner at p < .05.

Different from male with female partner at p < .05.

Table 2 displays the results of the two-tier Cragg’s Tobit alternative models, which controlled for the large set of covariates. The first and third columns show the estimated probability that parents spent any time engaged with children. The second column shows the amount of time engaged with children, and the fourth column shows the proportion of free time engaged with children, based on the condition that time is spent engaged in child-focused activities. Panel A shows estimates in relation to women with different-sex partners, whereas panel B presents estimates with men in different-sex partnerships as the reference group. Overall, women with same-sex partners were significantly more likely to spend any time engaged with children than women or men with different-sex partners. When examining number of minutes or proportion of time spent with children, conditional on spending any time with children (columns 2 and 4), the only statistically significant differences were between women and men with different-sex partners, with the former spending 3.6 % more of their nonwork time engaged with children than the latter.

Table 2.

Cragg Tobit alternative (two-tier) models: Time engaged with children in two-parent families

| Minutes With Children | % Nonwork Time With Children | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Probability of Time With Children | Minutes Conditional on Any Time | Probability of Time With Children | % of Time With Children Conditional on Any Time | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Panel A. Respondent Partnership Type (ref. = women with different-sex partners) | ||||

| Women with same-sex partners | 0.65* (0.27) | 55.68 (101.87) | 0.65* (0.27) | 4.05 (5.23) |

| Men with same-sex partners | 0.08 (0.45) | −28.37 (143.98) | 0.08 (0.45) | −3.36 (7.43) |

| Men with different-sex partners | −0.48*** (0.02) | −77.47*** (13.13) | −0.48*** (0.02) | −3.62*** (0.67) |

| Panel B. Respondent Partnership Type (ref. = men with different sex partners) | ||||

| Women with same-sex partners | 1.13*** (0.27) | 133.15 (102.25) | 1.13*** (0.27) | 7.67 (5.25) |

| Men with same-sex partners | 0.56 (0.45) | 49.10 (144.12) | 0.56 (0.45) | 0.26 (7.43) |

| Women with different-sex partners | 0.48*** (0.02) | 77.47*** (13.13) | 0.48*** (0.02) | 3.62*** (0.67) |

| Observations | 44,188 | 44,188 | 44,188 | 44,188 |

Notes: Robust standard errors are shown in parentheses. Model controls for respondent’s educational attainment, employment, age, race/ethnicity, whether respondent is a student, respondent’s partner’s education and employment, family income, children in the household (number, age, and gender), whether respondent lives in a metropolitan area, geographic region, and time-diary characteristics (weekend, summer month, year, and holiday).

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Key covariates, such as educational attainment and income, that tend to strongly predict time engaged with children in past research, and that predicted such time in our analyses, were more prevalent in the sample of respondents in same-sex partnerships. They did not, however, completely mediate the bivariate findings (full model results presented in Table 5 in the appendix).

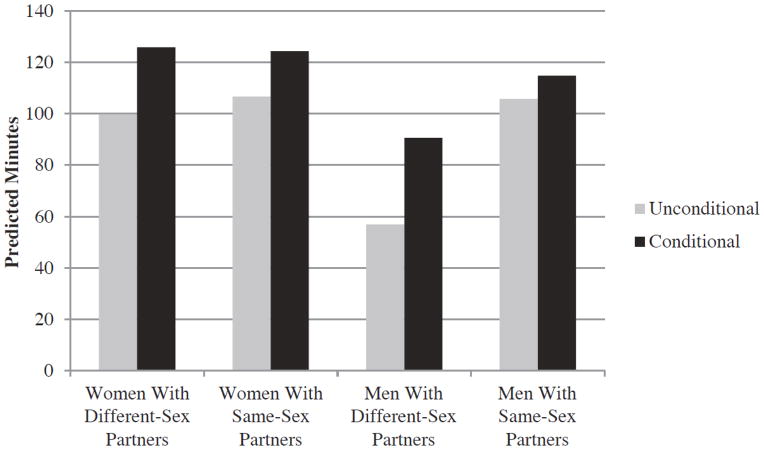

Figure 1 shows the unconditional and conditional predicted minutes engaged with children by family structure using the estimates from the Cragg models. In sum, women (regardless of their partners’ sex) and men in same-sex partnerships engaged in a similar amount of child-focused time with children—approximately 100 minutes overall, rising to about two hours among just those who engaged in any time with children. Again, however, the distinction among parents appears to be that men in different-sex partnerships engaged in significantly less time with children (although this apparent difference with the small subsample of men in same-sex partnerships was not statistically significant).

Fig. 1.

Unconditional and conditional predicted minutes spent engaged with children by family structure

Finally, we conducted sensitivity analyses to assess whether the differences in time engaged with children across family structures were driven by either the use of a child-focused assessment of time or the clear link between socioeconomic status differences and family structure in the sample. For the first analysis, we created a measure of total time spent where household children were present. For the second analysis, we created a matched sample on key sociodemographic indicators (i.e., sex, education, race/ethnicity, and income) of parents with different-sex partners to parents with same-sex partners. This created a control group of parents with different-sex partners that were not statistically different (at p < .10) on these key sociodemographic indicators from the more socioeconomically advantaged sample of parents in same-sex partnerships. These analyses (available on request from the authors) suggest that the findings persisted across a broader definition of time with children (e.g., time in any type of activity where household children were present) as well as when a subsample of sociodemographically similar respondents in different-sex partnerships were used as the comparison group.

Discussion

This study employed a potentially valuable representative data source to study same-sex families that has not been heretofore leveraged in this increasingly important field of research. Consistent with other studies on associations between same-sex family structures and child outcomes (and between such structures and parenting), we found few differences between same- and different-sex couples in child-focused time use, a family process previously implicated as an important mechanism of family structure effects on children. Although we came into this study with a focus on same-sex parents, one of the most compelling findings was about men in different-sex partnerships, who spent less time engaged in child-focused activities than men and women in all other types of partnerships. This finding is in line with prior research on differences in mothers’ and fathers’ time with children (Bianchi 2010, 2011) but goes beyond previous research by suggesting that this gender difference does not extend to fathers in same-sex partnerships.

Although the ATUS sample of respondents in same-sex partnerships was small, two findings are particularly interesting and, we argue, should spur future demographic research. First, women with same-sex partners were significantly more likely to report spending any time engaged with children than either women or men with different-sex partners. This finding is important considering that women with male partners might have been more likely to spend time with children because their male partners were typically less likely to also report doing so. These findings align with research suggesting less specialization in the household division of labor in same-sex partnerships (Giddings et al. 2014). Second, these findings suggest that children with parents in same-sex partnerships may experience more time investment, overall, than children of parents in different-sex relationships. By pairing the average unconditional predicted minutes of heterosexual men and women and doubling the minutes of women and men in same-sex partnerships, we extrapolated the findings to create a total amount of parental time investment within a household. Doing so revealed that children with same-sex parents experience, on average, approximately 3.5 hours of time investment per day versus just more than 2.5 hours for children with a mother and father in the household.

Of course, these results supporting the “no difference” paradigm could have resulted from low statistical power and/or unobserved confounds. These limitations are inherent to observational data, which need to be addressed in future research, and highlight the preliminary nature of this study. Indeed, the very small numbers of respondents identifying as being in same-sex partnerships in ATUS compared with a few other nationally representative data sets not focused on families with children (see Black et al. 2000 for a comparison) suggest that many respondents in same-sex partnerships are likely misclassified as being in different-sex partnerships (or single) (Gates 2009).

Future data collection needs to address these two issues by considering oversampling same-sex family structures and incorporating research questions that explicitly ask respondents to confirm partner gender and sexual identity. Fortunately, precedents exist for both, with oversampling of minority and hard-to-reach populations being common in large nationally representative data sets. For example, ATUS already oversamples households with Hispanic or non-Hispanic black householders to improve time-diary estimates for these demographic groups (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2014). Similarly, in preparation for the 2020 decennial census, the U.S. Census Bureau has begun testing new response categories that explicitly ask respondents to classify themselves in “opposite-sex” or “same-sex” relationships (U.S. Census Bureau 2014). More immediately, however, we argue that this research note highlights the importance of exploring data sets that already exist, potentially informing future research directions in family demography.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant 5 R24 HD042849, Population Research Center, and Grant 5 T32 HD007081, Training Program in Population Studies, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

Appendix

Table 3.

List of ATUS activity codes indicating time engaged with children

| Major Category | Second-Tier Category | Third-Tier Category |

|---|---|---|

| 03. Caring for and helping household members | 01. Caring for and helping household children | 01. Physical care for household children |

| 02. Reading to/with household children | ||

| 03. Playing with household children, not sports | ||

| 04. Arts and crafts with household children | ||

| 05. Playing sports with household children | ||

| 06. Talking with/listening to household children | ||

| 08. Organization and planning for household children | ||

| 09. Looking after household children (as a primary activity) | ||

| 10. Attending household children’s events | ||

| 11. Waiting for/with household children | ||

| 12. Picking up/dropping off household children | ||

| 99. Caring for and helping household children, n.e.c. | ||

|

| ||

| 02. Activities related to household children’s education | 01. Homework (household children) | |

| 02. Meetings and school conferences (household children) | ||

| 03. Home schooling of household children | ||

| 04. Waiting associated with household children’s education | ||

|

| ||

| 03. Activities related to household children’s health | 01. Providing medical care to household children | |

| 02. Obtaining medical care for household children | ||

| 03. Waiting associated household children’s health | ||

| 99. Activities related to household children’s health, n.e.c. | ||

Source: American Time Use Survey Lexicon, 2013. Retrieved from http://www.bls.gov/tus/lexiconwex2013.pdf

Table 4.

Sample description

| Total Sample, %/Mean | Women With Different-Sex Partners, %/Mean | Women With Same-Sex Partners, %/Mean | Men With Different-Sex Partners, %/Mean | Men With Same-Sex Partners, %/Mean | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Status | |||||

| Full-time employed | 65.3 | 44.7c | 57.5c | 86.0a,b,d | 43.6c |

| Part-time employed | 13.3 | 21.5c | 17.0c | 5.0a,b,d | 21.6c |

| Unemployed | 4.4 | 4.8c,d | 10.1 | 4.0a,d | 16.4a,c |

| Not working | 17.1 | 29.1c | 15.4c | 5.0a,b | 18.4 |

| Partner Employment Status | |||||

| Full-time employed | 63.1 | 81.7c,d | 72.9c | 44.4a,b | 63.1a |

| Part-time employed | 14.9 | 8.6c | 11.1c | 21.2a,b | 10.8 |

| Unemployed | 6.6 | 5.8c | 8.2 | 7.5a | 0.0 |

| Not working | 15.4 | 3.9c,d | 7.9 | 26.9a | 26.1a |

| Respondent Has College Degree | 35.9 | 36.9b,d | 49.6a,c | 34.8b,d | 66.8a,c |

| Partner Has College Degree | 37.2 | 36.5b,c,d | 60.1a,c | 37.7b,d | 66.0a,c |

| Family Income | $50–59,999 | $50–59,999b,c,d | $60–74,999a | $50–59,999a | $75–99,999a |

| Household Children Characteristics | |||||

| Number of children in household | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 2.0 |

| Child aged between 0–2 years | 28.5 | 28.8 | 26.4 | 28.3 | 30.6 |

| Child aged between 3–5 years | 28.7 | 28.7 | 22.9 | 28.7 | 18.0 |

| Child aged between 6–18 years | 74.7 | 74.2 | 69.3 | 75.1 | 73.5 |

| Female child in household | 68.2 | 67.8 | 75.4 | 68.7 | 69.5 |

| Male child in household | 70.0 | 70.2b | 43.8ac | 69.9b | 65.4 |

| N | 44,188 | 23,507 | 38 | 20,626 | 17 |

Notes: Unweighted ns, weighted %/means. Standard deviations are shown in parentheses. Chi-squared and t tests:

Different from female with male partner at p < .05.

Different from female with female partner at p <. 05.

Different from male with female partner at p < .05.

Different from male with male partner at p < .05.

Table 5.

Cragg Tobit alternative (two-tier) models: Time engaged with children in two-parent families

| Minutes With Children | % Nonwork Time With Children | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Probability of Time With Children | Minutes Conditional on Any Time | Probability of Time With Children | % of Time With Children Conditional on Any Time | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Respondent Partnership Type (ref. = women with different-sex partners) | ||||

| Women with same-sex partners | 0.65* (0.27) | 55.68 (101.87) | 0.65* (0.27) | 4.05 (5.23) |

| Men with same-sex partners | 0.08 (0.45) | −28.37 (143.98) | 0.08 (0.45) | −3.36 (7.43) |

| Men with different-sex partners | −0.48*** (0.02) | −77.47*** (13.13) | −0.48*** (0.02) | −3.62*** (0.67) |

| Respondent Characteristics | ||||

| College degree | 0.30*** (0.02) | 45.09*** (10.96) | 0.30*** (0.02) | 2.37*** (0.58) |

| Employment status (ref. = full-time) | ||||

| Part-time | 0.19*** (0.03) | 167.80*** (16.06) | 0.19*** (0.03) | 4.67*** (0.76) |

| Unemployed | 0.37*** (0.04) | 275.68*** (25.25) | 0.37*** (0.04) | 7.39*** (1.27) |

| Not in the labor force | 0.42*** (0.03) | 305.41*** (17.30) | 0.42*** (0.03) | 8.98*** (0.68) |

| Age | −0.02*** (0.00) | −5.37*** (0.97) | −0.02*** (0.00) | −0.28*** (0.05) |

| Race/ethnicity (ref. = non-Hispanic white) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic black | −0.19*** (0.04) | −126.08*** (24.09) | −0.19*** (0.04) | −7.50*** (1.31) |

| Hispanic white | −0.17*** (0.03) | −80.50*** (16.83) | −0.17*** (0.03) | −4.75*** (0.93) |

| Asian | −0.05 (0.05) | 14.83 (21.83) | −0.05 (0.05) | 0.81 (1.19) |

| Other race/ethnicity | −0.19*** (0.05) | −9.94 (27.52) | −0.19*** (0.05) | −0.19 (1.55) |

| Foreign-born | −0.13*** (0.03) | −1.23 (14.94) | −0.13*** (0.03) | 0.05 (0.82) |

| Student | −0.06 (0.04) | −117.58*** (19.57) | −0.06 (0.04) | −6.78*** (1.06) |

| Partner Characteristics | ||||

| College degree | 0.19*** (0.02) | 33.41** (11.22) | 0.19*** (0.02) | 1.85** (0.60) |

| Employment status (ref. = full-time) | ||||

| Part-time | −0.01 (0.02) | −19.65 (14.25) | −0.01 (0.02) | −1.01 (0.76) |

| Unemployed | −0.17*** (0.04) | −19.81 (22.10) | −0.17*** (0.04) | −1.74 (1.21) |

| Not in the labor force | −0.21*** (0.03) | −42.36* (19.17) | −0.21*** (0.03) | −2.56** (0.95) |

| Children Characteristics | ||||

| Number of household children | 0.19*** (0.01) | 42.76*** (6.39) | 0.19*** (0.01) | 2.36*** (0.34) |

| Child aged 0–2 years | 0.44*** (0.03) | 253.72*** (17.34) | 0.44*** (0.03) | 14.09*** (0.84) |

| Child aged 3–5 years | 0.36*** (0.02) | 66.96*** (10.57) | 0.36*** (0.02) | 4.16*** (0.57) |

| Child aged 6–18 years | −0.30*** (0.03) | −125.40*** (15.38) | −0.30*** (0.03) | −6.82*** (0.81) |

| Female child | 0.12*** (0.02) | 8.89 (10.79) | 0.12*** (0.02) | 0.56 (0.59) |

| Male child | 0.14*** (0.02) | 41.42*** (12.03) | 0.14*** (0.02) | 2.37*** (0.65) |

| Household and Geographic Characteristics | ||||

| Family income (scale 1–16) | 0.01*** (0.00) | 4.68** (1.81) | 0.01*** (0.00) | 0.28** (0.10) |

| Lives in a metropolitan area | 0.13*** (0.02) | 41.32** (13.02) | 0.13*** (0.02) | 2.27** (0.70) |

| Region (ref. = Northeast) | ||||

| Midwest | −0.10*** (0.03) | −26.32* (13.06) | −0.10*** (0.03) | −1.15+ (0.70) |

| South | −0.12*** (0.02) | −41.77** (12.69) | −0.12*** (0.02) | −1.95** (0.67) |

| West | −0.11*** (0.03) | −68.33*** (14.35) | −0.11*** (0.03) | −3.89*** (0.76) |

| Time-Diary Information | ||||

| Weekend day | −0.39*** (0.02) | 33.42*** (7.86) | −0.39*** (0.02) | −3.76*** (0.47) |

| Summer month | −0.29*** (0.02) | −35.01*** (10.24) | − 0.29*** (0.02) | −2.19*** (0.56) |

| Year (ref. = 2003) | ||||

| 2004 | 0.02 (0.04) | 3.35 (17.52) | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.12 (0.97) |

| 2005 | 0.05 (0.03) | −15.31 (17.95) | 0.05 (0.03) | −1.07 (0.99) |

| 2006 | −0.00 (0.04) | −19.94 (17.04) | −0.00 (0.04) | −1.09 (0.94) |

| 2007 | 0.05 (0.04) | −7.20 (17.48) | 0.05 (0.04) | −0.56 (0.95) |

| 2008 | 0.10** (0.04) | 5.40 (20.13) | 0.10** (0.04) | 0.10 (1.06) |

| 2009 | 0.07 (0.04) | 29.72 (19.16) | 0.07 (0.04) | 1.33 (1.03) |

| 2010 | 0.06 (0.04) | −7.56 (17.15) | 0.06 (0.04) | −0.75 (0.94) |

| 2011 | 0.02 (0.04) | 7.05 (18.36) | 0.02 (0.04) | 0.11 (0.99) |

| 2012 | 0.07* (0.04) | 27.89 (19.31) | 0.07* (0.04) | 1.31 (1.03) |

| 2013 | 0.08* (0.04) | 15.29 (18.49) | 0.08* (0.04) | 0.77 (1.02) |

| Holiday | −0.36*** (0.06) | −43.56 (34.21) | −0.36*** (0.06) | −7.36*** (2.06) |

| Constant | 0.90*** (0.08) | −460.44*** (51.36) | 0.90*** (0.08) | −14.45*** (2.46) |

| Sigma Constant | 243.84*** (8.12) | 15.67*** (0.42) | ||

| Observations | 44,188 | 44,188 | 44,188 | 44,188 |

Note: Robust standard errors are shown in parentheses.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Contributor Information

Kate C. Prickett, Email: kate.prickett@utexas.edu, The Population Research Center and Department of Sociology, University of Texas at Austin, 304 E. 23rd Street, Stop G1800, Austin, TX 78712-1699, USA

Alexa Martin-Storey, Département de psychoéducation, Université de Sherbrooke.

Robert Crosnoe, The Population Research Center and Department of Sociology, University of Texas at Austin.

References

- Bianchi S. Maternal employment and time with children: Dramatic change or surprising continuity? Demography. 2010;37:401–411. doi: 10.1353/dem.2000.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi S. Family change and time allocation in American families. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2011;638:21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Biblarz TJ, Stacey J. How does the gender of parents matter? Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Black D, Gates G, Sanders S, Taylor L. Demographics of the gay and lesbian population in the United States: Evidence from available systematic data sources. Demography. 2000;37:139–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. American Time Use Survey user’s guide: Understanding ATUS 2003 to 2013. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Burke WJ. Fitting and interpreting Cragg’s Tobit alternative using Stata. The Stata Journal. 2009;9:584–592. [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER, Avery LR, Dodson C, Goodman KD. Against nature: How arguments about the naturalness of marriage privilege heterosexuality. Journal of Social Issues. 2012;68:46–62. [Google Scholar]

- Cragg JG. Some statistical models for limited dependent variables with application to the demand for durable goods. Econometrica. 1971;39:829–844. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R, Cavanagh S. Families with children and adolescents: A review, critique, and future agenda. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:594–611. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch SR, Waters E, McNair R, Power J, Davis E. Parent-reported measures of child health and wellbeing in same-sex parent families: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2014 doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farr RH, Forssell SL, Patterson CJ. Parenting and child development in adoptive families: Does parental sexual orientation matter? Applied Developmental Science. 2010;14:164–178. [Google Scholar]

- Garret JR, Lantos JD. Marriage and the well-being of children. Pediatrics. 2013;131:559–563. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gartrell N, Bos H. US national longitudinal lesbian family study: Psychological adjustment of 17-year-old adolescents. Pediatrics. 2010;126:28–36. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates G. Same-sex spouses and unmarried partners in the American Community Survey, 2008. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Giddings L, Nunley JM, Schneebaum A, Zietz J. Birth cohort and the specialization gap between same-sex and different-sex couples. Demography. 2014;51:509–534. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joslin C. Searching for harm: Same-sex marriage and the well-being of children. Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review (CR-CL) 2011;46:81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kalil A, Ryan R, Corey M. Diverging destinies: Maternal education and the developmental gradient in time with children. Demography. 2012;49:1361–1383. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0129-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavner JA, Waterman J, Peplau LA. Can gay and lesbian parents promote healthy development in high-risk children adopted from foster care? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2012;82:465–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S. Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography. 2004;41:607–627. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter D. Same-sex parent families and children’s academic achievement. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2012;74:556–571. [Google Scholar]

- Rivers I, Poteat VP, Noret N. Victimization, social support, and psychosocial functioning among children of same-sex and opposite-sex couples in the United Kingdom. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:127–134. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfeld MJ. Nontraditional families and childhood progress through school. Demography. 2010;47:755–775. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanberg JF, Hofferth SL. Changes in children’s time with parents: United States, 1981–1997. Demography. 2001;38:423–436. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart J. Tobit or not Tobit? (BLS Working Papers) Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2014 census test: Questions. 2014 Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/2020-census/research-testing/testing-activities/2014-census-test/questions.html.

- Wainright JL, Russell ST, Patterson CJ. Psychosocial adjustment, school outcomes, and romantic relationships of adolescents with same-sex parents. Child Development. 2004;75:1886–1898. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]