Abstract

Purpose of review

There is currently much interest in the numbers of both glomeruli and podocytes. This interest stems from greater understanding of the effects of suboptimal fetal events on nephron endowment, the associations between low nephron number and chronic cardiovascular and kidney disease in adults, and the emergence of the podocyte depletion hypothesis.

Recent findings

Obtaining accurate and precise estimates of glomerular and podocyte number has proven surprisingly difficult. When whole kidneys or large tissue samples are available, design-based stereological methods are considered gold-standard because they are based on principles that negate systematic bias. However, these methods are often tedious and time-consuming, and oftentimes inapplicable when dealing with small samples such as biopsies. Therefore, novel methods suitable for small tissue samples, and innovative approaches to facilitate high through put measurements, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to estimate glomerular number and flow cytometry to estimate podocyte number, have recently been described.

Summary

This review describes current gold-standard methods for estimating glomerular and podocyte number, as well as methods developed in the past 3 years. We are now better placed than ever before to accurately and precisely estimate glomerular and podocyte number, and to examine relationships between these measurements and kidney health and disease.

Keywords: Glomerulus, podocyte, stereology, morphometry, nephron number, podocyte depletion

Introduction

In the mid-1980's, Barry Brenner and colleagues hypothesised that a glomerular deficit, either inherited or acquired, may increase the subsequent risk of developing hypertension [1, 2]. At about the same time, David Barker and his colleagues proposed the fetal origins hypothesis of adult disease, now known as the developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD) hypothesis, which originally postulated that suboptimal events during prenatal development increase the risk of cardiovascular disease in adulthood. The range of adult chronic diseases linked to fetal and early postnatal origins has now expanded to include cardiovascular disease [3, 4], renal disease [5, 6], obesity [7, 8] and diabetes [9, 10].

Similarly, the concept of podocyte depletion was conceived as a result of seminal contributions from Kriz [11-13], Wiggins [14-18], and others [19-24]. In short, the podocyte depletion hypothesis proposes that absolute podocyte depletion (loss of podocytes resulting in a decrease in the total number of podocytes in a glomerulus) or relative podocyte depletion (a decrease in the number of podocytes per unit volume of glomerulus) are both direct causes of focal and segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) [25]

To identify the genetic, developmental and environmental factors that lead to low nephron endowment, nephron loss and podocyte depletion, it is of fundamental importance to be able to count glomeruli and their podocytes in an accurate (no bias) and precise (low variance) manner. Surprisingly, this has proven to be difficult and controversial. The purpose of this review is to consider current valid methods for counting glomeruli and podocytes, the pros and cons of these methods, and potential new approaches.

Counting glomeruli

Why?

Brenner and colleagues were the first to report a link between a glomerular deficit and hypertension in adulthood, and subsequently identified associations between low glomerular number and the development of renal disease [26, 27]. At roughly the same time, Barker et al. [28] identified links between low birth weight and adult disease, including cardiovascular disease. Given that human birth weight and glomerular number are directly correlated [29], it seems likely that low birth weight results in low glomerular number, which may increase susceptibility to cardiovascular and renal disease in adulthood [6]. In this context, glomerular number serves as a surrogate marker of: (1) the feto-maternal environment using glomerular endowment at the completion of nephrogenesis, which is around birth or 36 weeks of gestation in humans; and (2) glomerular loss during childhood/adulthood using total number of glomeruli, which represents the number of glomeruli at a specific time-point (nephron endowment minus the number of glomeruli subsequently lost during postnatal life). Thus, the study of glomerular number has the potential to provide important insights into kidney health both before and after birth. While many methods for estimating glomerular number have been published, we briefly review below recently described approaches for estimating this key parameter.

Glomerular density

Most researchers and even renal pathologists use the terms glomerular cross-sections and glomeruli interchangeably. However, there is a big difference between glomerular cross-sections (2-dimensional samples of glomeruli – essentially glomerular bits and pieces as seen on histological sections) and whole glomeruli.

The study of glomerular density would appear the most pragmatic approach for counting glomeruli. In short, glomerular cross-sections observed in histological sections are counted and then expressed as glomerular number per unit area of section. Tsuboi et al [30-32] showed that low glomerular density was associated with increases in glomerular volume among patients with IgA nephropathy and obesity-related glomerulopathy. This group has also proposed that low glomerular density is directly associated with progression of IgA nephropathy [30, 31], idiopathic membranous nephropathy [33] and response to corticosteroid therapy in adult patients with minimal change nephrotic syndrome [34].

Despite the fact that glomerular density is frequently reported, and may be informative in particular scenarios, it introduces a series of potential confounders. For example, it is very clear that the number of glomerular cross-sections in a histological section depends not only on the number of glomeruli present, but also on glomerular size and shape [35, 36]. Indeed, an estimate of glomerular density from a histological section may have significant bias, because large glomeruli have a greater chance than small glomeruli of being sampled. Thus, in a setting of glomerular hypertrophy, the glomerular density will be seen to have increased, although in fact glomerular number has not increased at all. Furthermore, the number of glomeruli seen in a histological section is influenced by section thickness. Hence, the relationship between glomerular density in a section and the number of glomeruli in a kidney is complex and difficult to predict. Importantly, knowing the number of glomerular profiles per unit area of section tells us nothing about the total number of glomeruli in the kidney. This is therefore a far from ideal method for estimating glomerular number when sufficient tissue is available for adequate analysis.

Design-based stereology

The current gold-standard method for estimating glomerular number is based upon the disector principle described by Sterio [37]. This approach requires no knowledge or assumptions of glomerular geometry (size, shape), and when used correctly, provides unbiased estimates. Two general disector-based methods are available for counting glomeruli: the disector/Cavalieri principle [38] and the disector/fractionator principle [39]. These methods have been used to estimate glomerular number in a range of species, including humans and rodents [40, 41]. While these methods are considered the current gold-standard techniques, they have a number of limitations, including: (1) both require the analysis of a representative portion of the kidney, which means they are destructive and applicable only to terminal experiments – they can only provide cross-sectional data; (2) most studies have used a plastic embedding medium (such as Glycolmethacrylate) for dimensional stability, which requires expertise for tissue processing that may not be regularly available in laboratories; (3) both require systematic slicing and exhaustive sectioning, which are not only expensive, but also require significant skill; and (4) even if all of these requirements are met, the hands-on counting time ranges from approximately 6 hrs for a rat kidney to 8 hrs for a human kidney. For all of these reasons, very few laboratories have adopted these approaches. Therefore it is clear that a new method is urgently required.

A new approach

A new glomerular counting method utilising magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has recently been described [42-44]. Briefly, cationic ferritin (CF) perfused intravenously (rodents) or into excised kidneys (human), binds to anionic charges of the glomerular basement membrane (GBM), rendering the glomeruli visible with MRI. MRI of ex vivo CF-labeled kidneys provides estimates of glomerular number that are in excellent agreement with estimates obtained using the disector/fractionator approach [45].

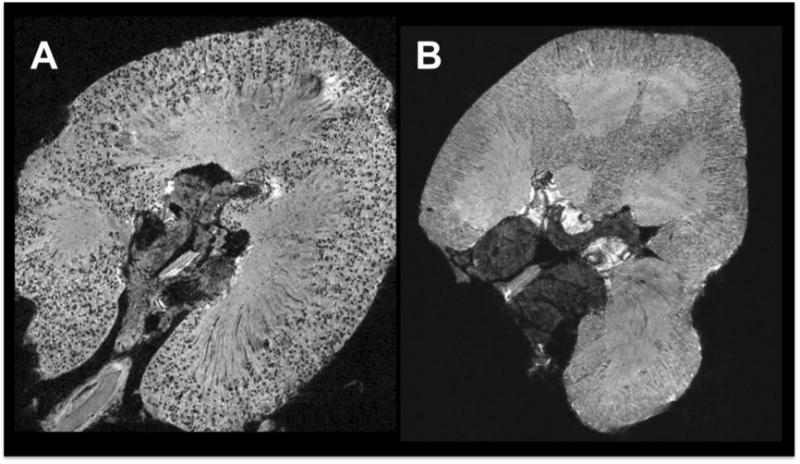

To date, MRI has been used to quantify the total number of glomeruli in rat and human kidneys [42-44]. MR images of a human kidney are shown in Figures 1A (CF-labeled) and 1B (negative control), respectively. Advantages of this new MRI approach include: (1) the kidney is imaged whole and therefore the need for embedding, slicing and sectioning is avoided;(2) the estimates can be obtained in approximately 1/6th of the hands-on time of stereology; and (3) since every labeled glomerulus is recorded, data on the glomerular size distribution is available, providing a potentially new and powerful technique for assessing glomerular growth, hypertrophy, shrinkage and size variability within individuals. However, a major disadvantage is that one needs access to a high field strength MRI scanner.

Figure 1.

Whether MRI can be reliably used to count and size glomeruli in vivo remains to be determined. A recent study by Qian et al [46] reported in vivo observation of rat glomeruli through signal amplification by a Wireless Amplified NMR Detector (WAND). Individual glomeruli were positively visualized by blood flow, and negatively visualized by ferritin and Mn2+. This is an exciting advance in the field, but further work is required to identify better/alternative contrast agents and/or to provide sufficient evidence of efficacy and safety. Bennett et al. [45] have discussed in greater detail the technical and regulatory challenges involved in developing MRI-based techniques for glomerular imaging.

Counting podocytes

Why?

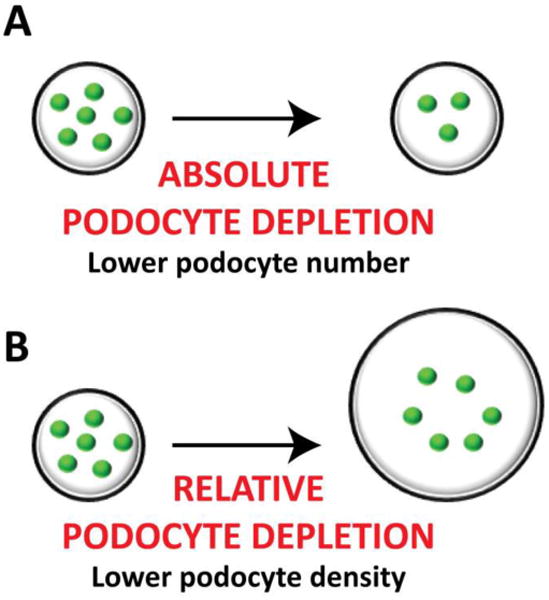

The podocyte depletion hypothesis has gained considerable attention in the last decade, mainly because it represents a unifying concept of renal pathology [17]. Podocyte depletion can be defined as “absolute” when the total number of healthy podocytes per glomerulus has decreased (Figure 2A), and as “relative” when there is no reduction in podocyte number but there is an increase in the glomerular filtration surface area (or glomerular volume) that leads to an effective reduction in podocyte density (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

In 2005, Wharram et al. [15] described a transgenic rat model in which the human diphtheria toxin receptor was specifically expressed in podocytes in order to achieve dose-dependent podocyte depletion. This landmark study showed that while death of less than 40% of podocytes lead to reversible reductions in renal function and transient proteinuria, loss of more than 40% of podocytes resulted in segmental sclerosis with sustained proteinuria and reduced renal function. More importantly, this study provided evidence that direct podocyte injury was sufficient for the development of progressive glomerular disease, and defined a critical threshold of podocyte depletion in rodents. In 2007, Wiggins proposed a podocyte depletion theory [17], placing the podocyte as the key cell in the development of glomerular diseases.

In the early 1990s, Nagata and Kriz [47] showed that in a setting of glomerular hypertrophy, podocytes are able to undergo hypertrophy in order to cover an enlarged capillary surface area, which leads to podocyte stress, podocyte loss, areas of denuded GBM and development of adhesions. Recently, Fukuda et al [18] confirmed these findings in a landmark study that highlighted how a “ mismatch” between podocyte volume and glomerular tuft growth can cause proteinuria, glomerulosclerosis and progression to renal failure.

The key parameter when studying podocyte depletion is podocyte number. A variety of methods have been used over the past 20-30 years to estimate podocyte number. These are briefly considered below, together with several new approaches described in the past 12 months.

Podocyte number per glomerular cross-section

The number of podocytes per glomerular cross-section is the most commonly used parameter for reporting podocyte number. However, while commonly reported, this parameter has serious flaws and the data are easily and frequently misinterpreted. The main problem is that podocyte nuclear profiles are counted. The number of these profiles is not only related to the number of podocytes present, but also to podocyte nuclear shape and size, as well as section thickness. Moreover, this method does not provide an estimate of the total number of podocytes in a glomerulus. Therefore, this parameter is of limited value when assessing podocyte depletion and should be avoided [48].

Model-based stereology

The stereological method of Weibel and Gomez [49] is also commonly used to estimate podocyte number. While this method provides estimates of total podocyte number per glomerulus, it is designated as “model-based” because it requires knowledge of the geometry (size, size distribution, shape) of podocyte nuclei. Generally, values for these geometric features are assumed rather than measured, and to the extent that these assumptions are inaccurate, there is the potential for the introduction of systematic bias. This can be acceptable in certain circumstances where insufficient tissue is available for a more comprehensive approach. These difficulties in counting podocytes were considered recently by Lemley et al. [48], who concluded that the disector/fractionator method was the preferred method when sufficient tissue was available, as for example in the case of whole autopsy kidneys.

Design-based stereology

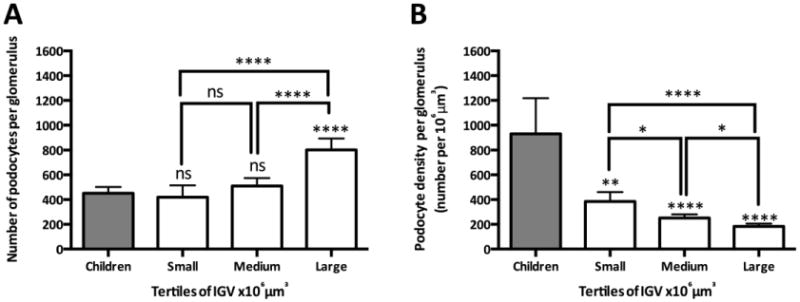

A disector/fractionator method for estimating podocyte number was recently described by Puelles et al [25]. This method combines serial sectioning of paraffin-embedded tissue, immunohistochemistry, confocal microscopy, the disector/fractionator principle (to count podocytes) and the disector/Cavalieri principle (to sample glomeruli and estimate their volume). This method has numerous advantages over previous methods, including: (1) estimates of total podocyte number in glomeruli of known volume (and thereby podocyte density) are obtained; (2) data describing the heterogeneity in total podocyte number and podocyte density between glomeruli from the same kidney are obtained; (3) total numbers of other cell types (such as endothelial and parietal epithelial cells (PECs)), and thereby cell number ratios (i.e. PEC/podocyte ratio) are obtained; and (4) additional information such as the cortical location of glomeruli is also available. Using this approach, Puelles et al [50] recently reported that large adult glomeruli contained more podocytes than glomeruli from young children, raising questions about the postnatal origin of these additional podocytes (Figure 3A). Puelles et al. [50] also showed that despite an increased number of podocytes, large adult glomeruli had lower podocyte densities than smaller glomeruli, indicating that these large glomeruli had relative podocyte depletion, possibly placing them at greater risk of subsequent pathological change (Figure 3B). These new insights into podocyte number and density were only obtained through the application of this new design-based method for podocyte counting.

Figure 3.

However, despite the powerful insights provided by this new approach, it has a number of limitations, including: (1) a considerable amount of time is required to obtain the confocal images (approx. 1.5hours per glomerulus) and count the podocytes (approx. 6 hours per glomerulus); (2) access to a laser confocal microscope is required; (3) significant technical expertise is required for the serial sectioning and podocyte counting; and (4) the method relies on specific immunostaining for podocyte identification, which may not always be reliable in pathological settings. Given the considerable amount of time to obtain estimates of podocyte number with this method, more cost-efficient methods are required. The two recently described methods detailed below are therefore of interest.

Counting podocytes with flow cytometry

Wanner et al [51] recently described a new method for counting podocytes in which glomeruli are isolated using magnetic beads, a single cell suspension is then obtained and podocytes are directly labelled with an anti-podocin antibody. Podocyte number is then determined using flow cytometry. The authors report a 99% overlap between genetically-labeled podocytes and podocytes detected with the antibody, suggesting this is a highly specific technique. While this is an excellent alternative that provides high throughput data, the final output is podocyte number per kidney rather than per glomerulus. Even if glomerular number could be calculated first, the final result would be an average representation of the whole kidney, without any insights on the variations between glomeruli, cortical zones or even the relationships between podocyte numbers and glomerular volume or numbers of other glomerular cell types. Nevertheless, this approach represents a potentially useful and high throughput technique for assessing global renal podocyte number.

Podocyte number in clinical biopsies

Estimating podocyte numbers in renal biopsies has also proved challenging, primarily because of the limited amount of tissue available. Venkatareddy et al [52] recently revived the stereological concept originally proposed by Abercrombie et al [53]. A key requirement of this method is estimation of the mean caliper diameter of podocyte nuclei. Venkatareddy et al [52] directly measured this caliper diameter, and then calculated a correction factor to correct podocyte counts for section thickness. Podocyte density was then estimated, and assuming glomeruli were spherical, average podocyte number per glomerulus was obtained. While design-based methods for estimating podocyte density may be theoretically preferable, they are also time-consuming and often not suitable for estimating podocyte number or density in renal biopsies. The method of Venkatareddy et al. [52] is robust, simple to use, utilizes commonly available technologies, can be applied to large numbers of glomeruli in a biopsy or kidney section, and can be adapted for automated biopsy analysis. As long as limitations and potential sources of bias are acknowledged and understood, this method may be a useful tool for estimating podocyte number in clinical samples.

Conclusions

There is currently much interest in understanding the importance of glomerular and podocyte number to adult health and disease. Obtaining accurate and precise estimates of glomerular and podocyte number in a timely fashion has proven difficult, although the past 2-3 years has witnessed the development of several new methods. More methodological advancements can be expected in the near future. These developments should improve our understanding of glomerular and podocyte numbers in adult health and disease, and ultimately contribute to the development of improved diagnostic and therapeutic options.

Acknowledgments

None

Financial support and sponsorship: Our glomerular studies were funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH 1 R01 DK065970-01), the NIH Center of Excellence in Minority Health (5P20M000534-02), the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (NHMRC) and the American Heart Association (South eastern Affiliate). Our podocyte research has been funded by grants from the NHMRC (grant numbers 606619 and 1065902). VGP received a Monash Research Graduate School Scholarship to support his PhD candidature.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- 1.Brenner BM. Nephron adaptation to renal injury or ablation. Am J Physiol. 1985;249(3 Pt 2):F324–37. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1985.249.3.F324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hostetter TH, et al. Hyperfiltration in remnant nephrons: a potentially adverse response to renal ablation. Am J Physiol. 1981;241(1):F85–93. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1981.241.1.F85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yeung EH, et al. Developmental Origins of Cardiovascular Disease. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2014;1(1):9–16. doi: 10.1007/s40471-014-0006-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ingelfinger JR, Nuyt AM. Impact of fetal programming, birth weight, and infant feeding on later hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2012;14(6):365–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2012.00660.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dorey ES, et al. Adverse prenatal environment and kidney development: implications for programing of adult disease. Reproduction. 2014;147(6):R189–98. doi: 10.1530/REP-13-0478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luyckx VA, et al. Effect of fetal and child health on kidney development and long-term risk of hypertension and kidney disease. Lancet. 2013;382(9888):273–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desai M, Beall M, Ross MG. Developmental origins of obesity: programmed adipogenesis. Curr Diab Rep. 2013;13(1):27–33. doi: 10.1007/s11892-012-0344-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yajnik CS. Transmission of obesity-adiposity and related disorders from the mother to the baby. Ann Nutr Metab. 2014;64 Suppl 1:8–17. doi: 10.1159/000362608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simmons RA. Developmental origins of diabetes: The role of oxidative stress. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26(5):701–8. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson JA, Regnault TR. In utero origins of adult insulin resistance and vascular dysfunction. Semin Reprod Med. 2011;29(3):211–24. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kretzler M, Koeppen-Hagemann I, Kriz W. Podocyte damage is a critical step in the development of glomerulosclerosis in the uninephrectomised-desoxycorticosterone hypertensive rat. Virchows Arch. 1994;425(2):181–93. doi: 10.1007/BF00230355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kriz W, Gretz N, Lemley KV. Progression of glomerular diseases: is the podocyte the culprit? Kidney Int. 1998;54(3):687–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kriz W, Endlich K. Hypertrophy of podocytes: a mechanism to cope with increased glomerular capillary pressures? Kidney Int. 2005;67(1):373–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim YH, et al. Podocyte depletion and glomerulosclerosis have a direct relationship in the PAN-treated rat. Kidney Int. 2001;60(3):957–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.060003957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wharram BL, et al. Podocyte depletion causes glomerulosclerosis: diphtheria toxin-induced podocyte depletion in rats expressing human diphtheria toxin receptor transgene. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(10):2941–52. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiggins JE, et al. Podocyte hypertrophy, “adaptation”, and “decompensation” associated with glomerular enlargement and glomerulosclerosis in the aging rat: prevention by calorie restriction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(10):2953–66. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005050488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wiggins RC. The spectrum of podocytopathies: a unifying view of glomerular diseases. Kidney Int. 2007;71(12):1205–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukuda A, et al. Growth-dependent podocyte failure causes glomerulosclerosis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23(8):1351–63. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012030271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sison K, et al. Glomerular structure and function require paracrine, not autocrine, VEGF-VEGFR-2 signaling. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21(10):1691–701. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010030295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eremina V, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor a signaling in the podocyte-endothelial compartment is required for mesangial cell migration and survival. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(3):724–35. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005080810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eremina V, et al. Glomerular-specific alterations of VEGF-A expression lead to distinct congenital and acquired renal diseases. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(5):707–16. doi: 10.1172/JCI17423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shankland SJ. The podocyte's response to injury: role in proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2006;69(12):2131–47. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiorina P, et al. Role of Podocyte B7-1 in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(7):1415–29. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tharaux PL, Huber TB. How many ways can a podocyte die? Semin Nephrol. 2012;32(4):394–404. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *25.Puelles VG, et al. Design-based stereological methods for estimating numbers of glomerular podocytes. Ann Anat. 2014;196(1):48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2013.04.007. This method provides unbiased estimates of total podocyte number in glomeruli of known volume, as well as estimates of podocyte density and ratios of podocyte numbers to other glomerular cell populations. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brenner BM. The etiology of adult hypertension and progressive renal injury: an hypothesis. Bull Mem Acad R Med Belg. 1994;149(1-2):121–5. discussion 125-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brenner BM, Mackenzie HS. Nephron mass as a risk factor for progression of renal disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 1997;63:S124–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barker DJ, Osmond C. Low birth weight and hypertension. BMJ. 1988;297(6641):134–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6641.134-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hughson M, et al. Glomerular number and size in autopsy kidneys: the relationship to birth weight. Kidney Int. 2003;63(6):2113–22. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsuboi N, et al. Changes in the glomerular density and size in serial renal biopsies during the progression of IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(3):892–9. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsuboi N, et al. Glomerular density in renal biopsy specimens predicts the long-term prognosis of IgA nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(1):39–44. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04680709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsuboi N, et al. Low glomerular density with glomerulomegaly in obesity-related glomerulopathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(5):735–41. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07270711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsuboi N, et al. Low glomerular density is a risk factor for progression in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(11):3555–60. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koike K, et al. Glomerular density-associated changes in clinicopathological features of minimal change nephrotic syndrome in adults. Am J Nephrol. 2011;34(6):542–8. doi: 10.1159/000334360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bertram JF. Analyzing renal glomeruli with the new stereology. Int Rev Cytol. 1995;161:111–72. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62497-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nyengaard JR. Stereologic methods and their application in kidney research. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(5):1100–23. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1051100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sterio DC. The unbiased estimation of number and sizes of arbitrary particles using the disector. J Microsc. 1984;134(Pt 2):127–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1984.tb02501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hinchliffe SA, et al. Human intrauterine renal growth expressed in absolute number of glomeruli assessed by the disector method and Cavalieri principle. Lab Invest. 1991;64(6):777–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bertram JF, et al. Why and how we determine nephron number. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29(4):575–80. doi: 10.1007/s00467-013-2600-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cullen-McEwen LA, Douglas-Denton RN, Bertram JF. Estimating total nephron number in the adult kidney using the physical disector/fractionator combination. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;886:333–50. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-851-1_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cullen-McEwen LA, et al. Estimating nephron number in the developing kidney using the physical disector/fractionator combination. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;886:109–19. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-851-1_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Beeman SC, et al. Measuring glomerular number and size in perfused kidneys using MRI. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2011;300(6):F1454–7. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00044.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Heilmann M, et al. Quantification of glomerular number and size distribution in normal rat kidneys using magnetic resonance imaging. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27(1):100–7. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **44.Beeman SC, et al. MRI-based glomerular morphology and pathology in whole human kidneys. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014;306(11):F1381–90. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00092.2014. The first report to use MRI to count and size glomeruli in human glomeruli. Represents an important step towards ultimately estimating glomerular number in patients with a suspected nephron deficit. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bennett KM, et al. The emerging role of MRI in quantitative renal glomerular morphology. Am J Physiol: Renal Physiol. 2013;304(10):F1252–7. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00714.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *46.Qian C, et al. Live nephron imaging by MRI. Am J Physiol: Renal Physiol. 2014;307(10):F1162–8. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00326.2014. A landmark report that for the first time used MRI to image glomeruli in vivo, both with and without contrast agent. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nagata M, Scharer K, Kriz W. Glomerular damage after uninephrectomy in young rats. I. Hypertrophy and distortion of capillary architecture. Kidney Int. 1992;42(1):136–47. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lemley KV, et al. Estimation of glomerular podocyte number: a selection of valid methods. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(8):1193–202. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012111078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weibel ER, Gomez DM. A principle for counting tissue structures on random sections. J Appl Physiol. 1962;(17):343–8. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1962.17.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **50.Puelles VG, et al. Podocyte number in children and adults: associations with glomerular size and numbers of other glomerular resident cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014070641. in press. Provides new insights into podocyte numbers in children and adults. Interestingly, while large adult glomeruli contain more podocytes than small glomeruli, their podocyte density is lower, suggesting these large glomeruli may be at heightened risk of pathological change. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *51.Wanner N, et al. Unraveling the role of podocyte turnover in glomerular aging and injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(4):707–16. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013050452. Describes a new technique utilising magentic beads and flow cytometry to estimate the total number of podocytes in whole mouse kidneys. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **52.Venkatareddy M, et al. Estimating podocyte number and density using a single histologic section. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(5):1118–29. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013080859. Extends the method of Abercrombie (1946) to count podocytes using single paraffin sections. The method is ideally suited to assessment of podocyte density in renal biopsies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Abercrombie M. Estimation of nuclear population from microtome sections. Anat Rec. 1946;94:239–47. doi: 10.1002/ar.1090940210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]