Abstract

Background

Prior studies assessing quality of life (QOL) in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) primarily included patients with preserved liver function and/or early HCC, leading to overestimation of QOL. Our study's aim was to evaluate the association of QOL with survival among a cohort of cirrhotic patients with HCC that was diverse with respect to liver function and tumor stage.

Methods

We conducted a prospective cohort study among cirrhotic patients with HCC from a large urban safety-net hospital between April 2011 and September 2013. Patients completed two self-administered surveys, the EORTC QLQ-C30, and QLQ-HCC18, prior to treatment. We used generalized linear models to identify correlates of QOL. Survival curves were generated using Kaplan–Meier analysis and compared using log rank test to determine whether QOL is associated with survival.

Results

A total of 130 treatment-naïve patients completed both surveys. Patients reported high cognitive and social function (median scores 67) but poor global QOL (median score 50) and poor role function (median score 50). QOL was associated with cirrhosis-related (p = 0.02) and tumor-related (p = 0.02) components of Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) tumor stage. QOL was associated with survival on univariate analysis (HR 0.37, 95 % CI 0.16–0.85) but became nonsignificant (HR 0.82, 95 % CI 0.37–1.80) after adjusting for BCLC stage and treatment. Role functioning was significantly associated with survival (HR 0.40, 95 % CI 0.20–0.81), after adjusting for Caucasian race (HR 0.31, 95 % CI 0.16–0.59), BCLC stage (HR 1.51, 95 % CI 0.21– 1.89), and treatment (HR 0.57, 95 % CI 0.33–0.97).

Conclusions

Role function has prognostic significance and is important to assess in patients with HCC.

Keywords: Liver cancer, Quality of life, Role function, Prognosis

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1]. Its incidence in the USA and Europe is increasing due to a growing number of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) cases [2]. Underlying cirrhosis is the strongest risk factor for HCC development, and HCC is one of the leading causes of death among those with cirrhosis [1].

Prognosis for HCC is based on degree of hepatic function, performance status, and tumor burden. Patients with preserved hepatic function, good performance status, and early stage HCC can undergo curative treatments with 5-year survival rates approaching 70 % [3]. Unfortunately, most HCC patients have 5-year survival rates below 18 % due to detection at late stages and underuse of curative treatment [4–6]. Nearly two-thirds of HCC are found at advanced stages due to poor sensitivity of surveillance tests and underuse of surveillance in at-risk individuals [7–10].

Health-related quality of life (QOL) is an outcome of increasing interest after studies suggested it may be an independent prognostic factor in HCC patients [11–13]. Patients with HCC suffer from morbidity and poor QOL due to both hepatic dysfunction and tumor-related symptoms [14–16]. They report lower QOL than the general population and than those with liver disease but without HCC [15, 16]. Poor QOL is driven by several symptoms including fatigue, weakness, anorexia, abdominal pain/bloating, and depression [14, 16–19].

Two widely used instruments to assess QOL in cancer patients are the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Generic (FACT-G) and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QOL questionnaire (QLQ), the EORTC QLQ-C30. Both instruments can be supplemented with disease-specific QOL modules to collect more detailed information. The EORTC QLQ-HCC18 was developed as an HCC-specific tool to supplement the EORTC QLQ-C30 [20]. However, most prior studies have primarily included patients with preserved liver function and/or early stage HCC, potentially leading to an overestimation of QOL [20, 21]. The objectives of our study were to: (1) characterize QOL among a cohort of HCC patients that is diverse with respect to liver function and tumor stage, (2) identify correlates of QOL, and (3) evaluate if QOL is associated with survival.

Methods

Study population

We conducted a prospective cohort study of cirrhotic patients with HCC at Parkland Health and Hospital System (Parkland). As the safety-net system for Dallas County, Parkland has a mission to provide care to low-income, underinsured, and vulnerable populations. Treatment-naïve cirrhotic patients with HCC were identified and recruited from the Parkland Liver Tumor Clinic between April 2011 and September 2013. This clinic provides outpatient care for all HCC patients at Parkland and is staffed by hepatologists, surgeons, medical oncologists, and interventional radiologists [22]. We used treatment-naïve patients to avoid confounding from any post-treatment adverse effects. Cirrhosis was defined as stage 4 fibrosis on biopsy or a cirrhotic-appearing liver on imaging in combination with portal hypertension (e.g. varices, ascites, or splenomegaly). HCC diagnosis was based on American Association for the Study of Liver Disease criteria [3]. Patients were excluded if they had received prior HCC-directed treatment, had significant encephalopathy precluding consent, or refused consent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at UT Southwestern Medical Center (Dallas, TX).

Data collection

Eligible patients were approached before their clinic appointment and consented to complete two self-administered surveys: the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-HCC18. Patients completed the surveys at initial presentation to the clinic, prior to HCC-directed therapy. Surveys were available in English and Spanish. The EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire incorporates a range of QOL issues, including a global QOL scale, five functional scales (physical, role, cognitive, emotional and social), three symptom scales (fatigue, pain and nausea/vomiting), and six single items (dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea and financial difficulties). Role functioning assesses a patient's ability to perform daily activities, leisure time activities, and/or work. The QLQ-HCC18 consists of one functional scale (body image), five symptom scales (fatigue, jaundice, nutrition, pain, and fever) and two single items (abdominal pain and sexual interest). High scores for QOL and functional scales represent high levels of QOL and functioning, whereas high scores for symptom scales represent more severe symptoms. Missing data consisted of less than 5 % of answers and were imputed per EORTC scoring guidelines. Scoring for each survey was also performed per EORTC scoring guidelines [20].

Patient demographics, clinical history, laboratory data, and imaging results were obtained through review of medical records by two investigators (A.S. and A.Y.), as previously described [6, 23]. Age, gender, race/ethnicity, insurance status, marital status, and alcohol and smoking history were recorded. Data regarding liver disease included underlying etiology (HCV, hepatitis B virus, alcohol-related liver disease, NASH, or other) and presence of ascites or encephalopathy. Patients with HCV infection and alcohol abuse were categorized as HCV infection. Performance status was classified according to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) criteria [24, 25]. Laboratory data of interest included platelet count, creatinine, bilirubin, albumin, international normalized ratio (INR), alpha fetoprotein (AFP), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Tumor characteristics were determined by 4-phase CT or MRI, interpreted by radiologists at our institution, and the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) system was used for tumor staging [26].

Statistical analysis

We used generalized linear models to identify correlates of global QOL, functional scores, and symptoms scores. Patient and tumor characteristics from time of survey administration were treated as independent variables. Multivariate regression models were conducted using factors significant on univariate analyses, with statistical significance being defined as p < 0.05. When clinical or statistical multicollinearity was present, two sets of multivariate models were created: one excluding any collinear variables and another including all variables.

To determine whether QOL is predictive of survival, survival curves were generated using Kaplan–Meier analysis and compared using log rank test. Survival was measured from day of HCC diagnosis to date of death, with patients censored at date of last clinic visit or end of study on November 1, 2013. We used Cox proportional hazards models to identify factors that influenced survival, with statistical significance being defined as p < 0.05. All data analysis was conducted using Stata 11 (StataCorp).

Results

Patient characteristics

From April 2011 to September 2013, 291 HCC patients were seen in the Parkland Liver Tumor Clinic. Of these patients, 61 did not consent to participate or left prior to being approached, 68 had undergone prior treatment and 32 failed to complete most of the survey. Therefore, 130 treatment-naïve HCC patients were enrolled and completed the QLQ-C30 and QLQ-HCC18 questionnaires. Median age of patients was 57 years (range, 35–80) and 78 % were male. The cohort was racially diverse with 23 % nonHispanic Caucasians, 33 % African-Americans, and 38 % Hispanic Caucasians. The most common etiologies of cirrhosis were HCV (73 %), alcohol-induced (9 %), and NASH (12 %). The cohort was diverse with respect to liver disease and tumor stage (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

| Patient characteristics | All patients (n = 130) |

|---|---|

| Age | 57.4 (35–80) |

| Gender (% male) | 101 (77.7 %) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 30 (23.1 %) |

| Black | 43 (33.1 %) |

| Hispanic | 50 (38.4 %) |

| Asian | 7 (5.4 %) |

| Etiology | |

| Hepatitis C | 95 (73.1 %) |

| Hepatitis B | 8 (6.2 %) |

| Alcohol | 12 (9.2 %) |

| NASH | 15 (11.5 %) |

| Insurance status | |

| Parkland Health Plusa | 56 (43.1 %) |

| Medicare | 19 (14.6 %) |

| Medicaid | 52 (40 %) |

| Private insurance | 3 (2.3 %) |

| Marriage status | |

| Single | 55 (42.3 %) |

| Married | 35 (26.9 %) |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 27 (20.8 %) |

| Alcohol (% active) | 30 (23.1 %) |

| Smoking (% active) | 55 (42.3 %) |

| Presence of ascites | 58 (44.6 %) |

| Presence of hepatic encephalopathy | 25 (19.2 %) |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.15 (0.2–23.8) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.2 (1.8–4.6) |

| INR | 1.2 (1–5) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.8 (0.4–9.4) |

| Functional status (% ECOG 0-1) | 102 (78.5 %) |

| MELD score | 11 (6–38) |

| Liver function | |

| Child-Pugh A | 56 (43.1 %) |

| Child-Pugh B | 45 (34.6 %) |

| Child-Pugh C | 29 (22.3 %) |

| Tumor stage | |

| BCLC stage A | 52 (40.0 %) |

| BCLC stage B | 22 (16.9 %) |

| BCLC stage C | 26 (20.0 %) |

| BCLC stage D | 30 (23.1 %) |

Parkland Health Plus is a subsidy program to pay for medical care, including HCC-related care, for uninsured and underinsured patients living in Dallas County

BCLC Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, INR international normalized ratio, MELD Model for End-Stage Liver Disease, NASH nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

Quality of life scores

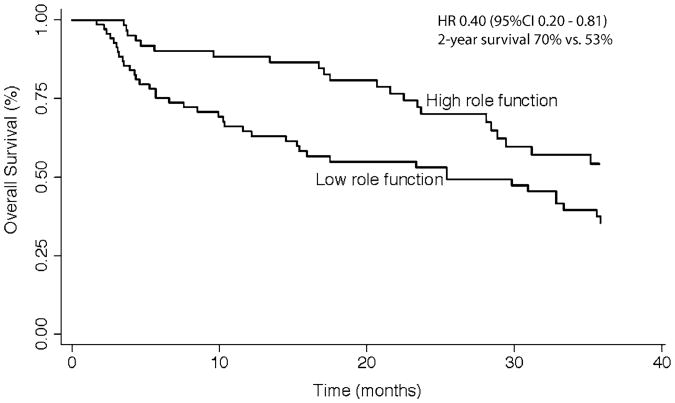

QOL results are summarized in Table 2 and Fig. 1. Median global QOL was 50, with only 12 % of patients having global QOL greater than 75. Twelve patients reported global QOL of 0, while 11 reported a score of 100. The highest functional scales were cognitive function (median score 67) and social function (median score 67), while role function was the lowest scored (median score 50). Among symptom scales, insomnia, loss of sexual desire, and financial difficulty were most highly scored, while the lowest scored symptoms were fever, nausea/vomiting, and diarrhea.

Table 2. Quality of life among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.

| N | Median (range) | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| QLQ-C30 baseline scores | |||

| Global quality of life | 130 | 50.0 (0–100) | 47.6 (28.6) |

| Physical functioning | 130 | 60.0 (–100) | 60.1 (29.8) |

| Role functioning | 130 | 50.0 (0–100) | 54.2 (36.4) |

| Emotional functioning | 130 | 62.5 (0–100) | 57.3 (31.6) |

| Cognitive functioning | 130 | 66.7 (0–100) | 64.6 (33.1) |

| Social functioning | 130 | 66.7 (0–100) | 58.6 (36.0) |

| Fatigue | 130 | 55.6 (0–100) | 54.8 (32.6) |

| Nausea and vomiting | 130 | 16.7 (0–100) | 21.3 (25.2) |

| Pain | 130 | 50 (0–100) | 50.8 (36.4) |

| Dyspnea | 130 | 33.3 (0–100) | 46.2 (38.4) |

| Insomnia | 130 | 66.7 (0–100) | 52.6 (39.8) |

| Appetite loss | 129 | 33.3 (0–100) | 36.4(34.3) |

| Constipation | 130 | 33.3 (0–100) | 30.3 (35.3) |

| Diarrhea | 128 | 0 (0–100) | 20.2 (29.9) |

| Financial difficulties | 129 | 66.7 (0–100) | 59.4 (40.4) |

| HCC18 baseline scores | |||

| Fatigue | 130 | 55.6 (0–100) | 52.8 (32.3) |

| Jaundice | 128 | 33.3 (0–100) | 34.2 (30.6) |

| Nutrition | 130 | 33.3 (0–100) | 36.8 (26.3) |

| Pain | 129 | 33.3 (0–100) | 37.9 (31.1) |

| Fever | 130 | 16.7 (0–100) | 20.9 (23.8) |

| Abdominal swelling | 130 | 33.3 (0–100) | 43.6 (40.8) |

| Sexual interest | 125 | 66.7 (0–100) | 51.7 (44.9) |

| Body image | 129 | 66.7 (0–100) | 58.4 (31.7) |

HCC hepatocellular carcinoma, N number of patients, SD standard deviation, QLQ quality of life questionnaire

Fig 1.

Quality of life in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. a Quality of life scores according to QLQ-C30 questionnaire. b Quality of life scores according to QLQ-HCC18 Questionnaire

Correlates of global quality of life

Variables associated with global QOL in univariate analyses included HIV serostatus (p = 0.02), bilirubin ≥2 mg/dL (p < 0.001), ascites (p = 0.03), hepatic encephalopathy (p = 0.03), Child-Pugh score (p = 0.02), multifocal tumor burden (p = 0.03), and BCLC stage (p = 0.02). Global QOL was not associated with age (p = 0.35), gender (p = 0.40), race (p = 0.32), or etiology of liver disease (p = 0.47). The median QOL for patients with viral liver disease was 0.50, compared to 0.58 in those with nonviral liver disease. Initially, we included BCLC stage and HIV serostatus in a multivariate generalized linear model given clinical collinearity between variables (Child-Pugh, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, bilirubin, and tumor burden are components of BCLC stage). In multivariate analysis, BCLC stage (coefficient −0.2, 95 % CI −0.3, −0.01) and HIV serostatus (coefficient 0.88, 95 % CI 0.09, 1.67) were significantly associated with global QOL. Patients with BCLC stage A tumors had median QOL scores of 54, compared to 47 for stage B or C tumors and 39 for stage D tumors. When evaluating components of BCLC stage, this association was related to both Child-Pugh score (p = 0.02) and tumor burden (p = 0.02).

Variables associated with role functioning in univariate analyses included black race (p = 0.04), ECOG performance status (p < 0.001), hepatic encephalopathy (p < 0.001), ascites (p = 0.001), bilirubin ≥2 mg/dL (p = 0.02), Child-Pugh score (p < 0.001), multifocal tumor burden (p = 0.02), portal vein invasion (p = 0.03), and BCLC stage (p < 0.001). Initially, we only included BCLC stage and black race in a multivariate generalized linear model given clinical collinearity between variables (as described above). In multivariate analysis, black race (coefficient 0.61, 95 % CI 0.07, 1.15) and BCLC stage (coefficient −0.51, 95 % CI −0.73, −0.29) were significantly associated with role functioning. When evaluating components of BCLC stage, this association was related to the presence of hepatic encephalopathy (p = 0.02) and ECOG status (p = 0.001).

Quality of life and survival

During follow-up, 77 patients died, seven were lost to follow up, and 46 remained alive. All patients lost to follow-up were doing well at the time of their last visit, with intact liver function and limited tumor burden. Median survival of the cohort was 13.0 months, with 1- and 2-year survival rates of 53 and 30 % respectively. Demographic and clinical variables significant on univariate analysis included Caucasian race (p = 0.003), ECOG status (p < 0.001), Child-Pugh score (p = 0.02), tumor nodules (p < 0.001), tumor diameter (p < 0.001), portal vein invasion or distant metastases (p < 0.001), BCLC stage (p < 0.001), and HCC-directed treatment receipt (p < 0.001). Given clinical collinearity between BCLC stage and several variables (as described above), we only included Caucasian race, BCLC stage, and treatment receipt in multivariate models.

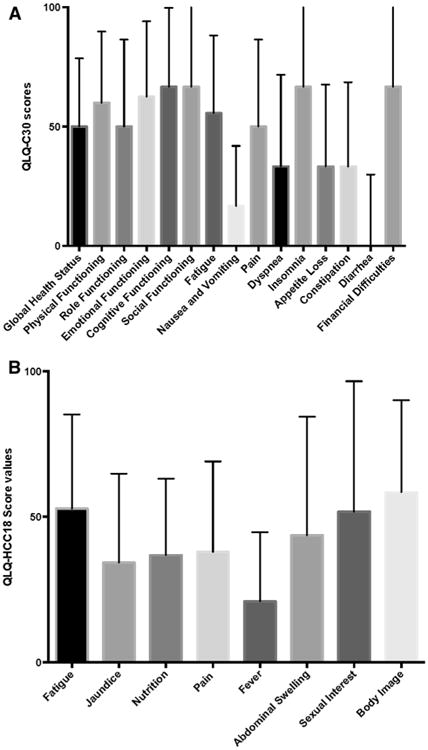

Several QOL measures were associated with survival in univariate analyses (Table 3). Notable predictors of survival in univariate analyses included global QOL, performance function, and role function. Significant predictors of improved survival on multivariate analysis included Caucasian race (HR 0.31, 95 % CI 0.16–0.59), BCLC stage (HR 1.51, 95 % CI 1.21–1.89), HCC-directed treatment receipt (HR 0.57, 95 % CI 0.33–0.97), and role function (HR 0.40, 95 % CI 0.20–0.81). Global QOL and performance function were no longer significantly associated with survival in multivariate analysis. When dichotomized at the median score of 0.50, patients with low role functioning had 1- and 2-year survival rates of 65 and 53 % respectively, compared to 88 and 70 % for those with high role functioning (Fig. 2).

Table 3. Quality of life measures associated with overall survival on univariate analysis.

| Variable | HR (95 % CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Global quality of life | 0.37 (95 % CI 0.16–0.85) | 0.02 |

| Role function | 0.27 (95 % CI 0.14–0.54) | < 0.001 |

| Performance function | 0.17 (95 % CI 0.08–0.38) | < 0.001 |

| Social function | 0.99 (95 % CI 0.98–1.00) | < 0.001 |

| Fatigue | 1.01 (95 % CI 1.00–1.02) | 0.002 |

| Pain | 1.01 (95 % CI 1.00–1.02) | 0.003 |

| Nutrition | 1.01 (95 % CI 1.00–1.02) | < 0.001 |

| Dyspnea | 1.01 (95 % CI 1.00–1.01) | 0.02 |

| Insomnia | 1.01 (95 % CI 1.00–1.01) | 0.02 |

| Financial difficulties | 1.01 (95 % CI 1.00–1.01) | 0.02 |

| Abdominal swelling | 1.01 (95 % CI 1.00–1.01) | 0.007 |

| Body image | 1.01 (95 % CI 1.00–1.01) | 0.002 |

| Sexual interest | 0.99 (95 % CI 0.98–1.00) | 0.02 |

CI confidence interval, HR hazard ratio

Fig 2. Overall survival stratified by role functioning.

Discussion

To our knowledge, our study is one of the first to describe QOL among treatment-naïve patients with cirrhosis and HCC using the EORTC QLQ-C30 and QLQ-HCC18. We found patients had fair QOL, with the largest deficits in role functioning. Role functioning was significantly associated with survival after adjusting for BCLC stage and HCC-directed treatment. Global QOL and performance functioning were associated with survival on univariate analysis but became nonsignificant after adjusting for important clinical variables. Finally, poor QOL was driven by a combination of tumor burden and liver dysfunction, underscoring the importance of managing both HCC and cirrhosis-related symptoms.

QOL has been increasingly recognized as an important endpoint in clinical research and clinical practice in addition to traditional end points of tumor response and survival. Understanding QOL is important in clinical practice for prioritizing issues to address, facilitating shared decision-making, and monitoring treatment response [27]. We found global QOL and role functioning might be associated with survival in patients with HCC, further supporting its informative role. Studies are needed to characterize the prognostic role of QOL longitudinally when used in combination with tumor stage.

Our study also allowed us to explore if QOL is driven by tumor burden, liver dysfunction, or a combination of these factors. The finding that liver dysfunction and tumor burden were equally associated with QOL highlights the importance of managing both conditions in patients with HCC. This can be challenging given these factors can be competing interests. For example, TACE is associated with a 20 % risk of hepatic decompensation, which must be weighed against tumor response rates [28]. Multidisciplinary management of HCC patients may be an effective means of managing both cirrhosis-related and tumor-related issues and may improve outcomes [22].

Similar to other studies, patients reported fair social and cognitive functioning but low role functioning [12, 13, 15]. Patients with HCC might be particularly susceptible to poor role functioning given cirrhosis-related complications, e.g. ascites or encephalopathy, and HCC-related symptoms, e.g. weakness or fatigue, can impair role functioning. Furthermore, cirrhosis is a catabolic state, with high rates of muscle atrophy and physical weakness [29]. The importance of assessing role functioning was highlighted in our study given its association with survival. Further studies are needed to determine whether interventions to improve role functioning can improve survival.

Our study had some limitations. Although we found a significant association between role functioning and survival, we only found a trend toward association between global QOL and survival. It is possible we may have found a significant difference with a larger sample size. Second, it was performed in a single large safety-net hospital and may not be generalized to other practice settings. Third, similar to all survey studies, our study was limited by possible response bias and recall bias. Finally, our study was also limited by possible unmeasured confounders and missing data despite its prospective nature.

In summary, patients with cirrhosis and HCC report fair QOL, with the largest deficits in role functioning. There was a significant association between role functioning and survival, after adjusting for BCLC tumor stage and treatment, highlighting the importance of assessing QOL in patients with HCC. Poor QOL appears to be driven by both tumor burden and the degree of liver dysfunction, which underscores the importance of managing both the HCC and cirrhosis-related complications in these patients. Further longitudinal studies are necessary to determine how QOL can be incorporated into prognostic systems and help providers make treatment decisions for cirrhotic patients with HCC.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted with support from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award KL2TR001103. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest None of the authors have any conflicts of interest relevant to this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Adam Meier, Department of Internal Medicine, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA.

Adam Yopp, Department of Surgery, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA; Harold C. Simmons Cancer Center, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA.

Huram Mok, Department of Internal Medicine, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA.

Pragathi Kandunoori, Department of Internal Medicine, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA.

Jasmin Tiro, Harold C. Simmons Cancer Center, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA; Department of Clinical Sciences, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA.

Amit G. Singal, Email: amit.singal@utsouthwestern.edu, Department of Internal Medicine, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA; Harold C. Simmons Cancer Center, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA; Department of Clinical Sciences, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA; Division of Digestive and Liver Diseases, Dedman Scholar of Clinical Care, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5959 Harry Hines Blvd, POB 1, Suite 420, Dallas, TX 75390-8887, USA.

References

- 1.El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1264–1273.e1261. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag HB, Davila JA, Petersen NJ, McGlynn KA. The continuing increase in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States: An update. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2003;139:817–823. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: An update. Hepatology. 2010;53:1–35. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altekruse SF, McGlynn KA, Dickie LA, Kleiner DE. Hepatocellular carcinoma confirmation, treatment, and survival in surveillance, epidemiology, and end results registries, 1992–2008. Hepatology. 2012;55:476–482. doi: 10.1002/hep.24710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan D, Yopp A, Beg MS, Gopal P, Singal AG. Meta-analysis: Underutilisation and disparities of treatment among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2013;38:703–712. doi: 10.1111/apt.12450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singal AG, Waljee AK, Patel N, Chen EY, Tiro JA, et al. Therapeutic delays lead to worse survival among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2013;11:1101–1108. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singal AG, Conjeevaram HS, Volk ML, Fu S, Fontana RJ, et al. Effectiveness of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in patients with cirrhosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prevention. 2012;21:793–799. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singal AG, Nehra M, Adams-Huet B, Yopp AC, Tiro JA, et al. Detection of hepatocellular carcinoma at advanced stages among patients in the HALT-C trial: Where did surveillance fail? American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;108:425–432. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singal AG, X L, Tiro J, Kandunoori P, Adams-Huet B, et al. Racial, social, and clinical determinants of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance. The American Journal of Medicine. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singal AG, Yopp A, Skinner CS, Packer M, Lee WM, et al. Utilization of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance among American patients: A systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2012;27:861–867. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1952-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bonnetain F, Paoletti X, Collette S, Doffoel M, Bouche O, et al. Quality of life as a prognostic factor of overall survival in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: Results from two French clinical trials. Quality of Life Research. 2008;17:831–843. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9365-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Diouf M, Filleron T, Barbare JC, Fin L, Picard C, et al. The added value of quality of life (QoL) for prognosis of overall survival in patients with palliative hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Hepatology. 2013;58:509–521. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeo W, Mo FK, Koh J, Chan AT, Leung T, et al. Quality of life is predictive of survival in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Annals of Oncology. 2006;17:1083–1089. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kondo Y, Yoshida H, Tateishi R, Shiina S, Mine N, et al. Health-related quality of life of chronic liver disease patients with and without hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2007;22:197–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steel JL, Chopra K, Olek MC, Carr BI. Health-related quality of life: Hepatocellular carcinoma, chronic liver disease, and the general population. Quality of Life Research. 2007;16:203–215. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bianchi G, Loguercio C, Sgarbi D, Abbiati R, Brunetti N, et al. Reduced quality of life of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2003;35:46–54. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(02)00011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan SY, Eiser C, Ho MC. Health-related quality of life in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review. Clinical Gastroenterol and Hepatology. 2010;8(7):559–564. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Les I, Doval E, Flavia M, Jacas C, Cardenas G, et al. Quality of life in cirrhosis is related to potentially treatable factors. Europen Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2010;22:221–227. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283319975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mikoshiba N, Miyashita M, Sakai T, Tateishi R, Koike K. Depressive symptoms after treatment in hepatocellular carcinoma survivors: Prevalence, determinants, and impact on health-related quality of life. Psycho-Oncology. 2013;22(10):2347–2353. doi: 10.1002/pon.3300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blazeby JM, Currie E, Zee BC, Chie WC, Poon RT, et al. Development of a questionnaire module to supplement the EORTC QLQ-C30 to assess quality of life in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, the EORTC QLQ-HCC18. European Journal of Cancer. 2004;40:2439–2444. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chie WC, Blazeby JM, Hsiao CF, Chiu HC, Poon RT, et al. International cross-cultural field validation of an European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer questionnaire module for patients with primary liver cancer, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality-of-life questionnaire HCC18. Hepatology. 2012;55:1122–1129. doi: 10.1002/hep.24798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yopp AC, Mansour JC, Beg MS, Arenas J, Trimmer C, et al. Establishment of a multidisciplinary hepatocellular carcinoma clinic is associated with improved clinical outcome. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2013;21(4):1287–1295. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3413-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singal AG, Yopp AC, Gupta S, Skinner CS, Halm EA, et al. Failure rates in the hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance process. Cancer Prevention Research. 2012;5:1124–1130. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Borja MT, Chow E, Bovett G, Davis L, Gillies C. The correlation among patients and health care professionals in assessing functional status using the karnofsky and eastern cooperative oncology group performance status scales. Support Cancer Therapy. 2004;2:59–63. doi: 10.3816/SCT.2004.n.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Kock I, Mirhosseini M, Lau F, Thai V, Downing M, et al. Conversion of Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG) to Palliative Performance Scale (PPS), and the inter-changeability of PPS and KPS in prognostic tools. Journal of Palliative Care. 2013;29:163–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cillo U, Vitale A, Grigoletto F, Farinati F, Brolese A, et al. Prospective validation of the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging system. Journal of Hepatology. 2006;44:723–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higginson IJ, Carr AJ. Measuring quality of life: Using quality of life measures in the clinical setting. BMJ. 2001;322:1297–1300. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7297.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan AO, Yuen MF, Hui CK, Tso WK, Lai CL. A prospective study regarding the complications of transcatheter intraarterial lipiodol chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:1747–1752. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donaghy A. Issues of malnutrition and bone disease in patients with cirrhosis. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2002;17:462–466. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]