Abstract

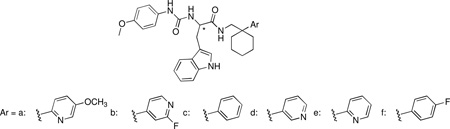

N-formyl peptide receptors (FPRs) are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that play critical roles in inflammatory reactions, and FPR-specific interactions can possibly be used to facilitate the resolution of pathological inflammatory reactions. We here report the synthesis and biological evaluation of six pairs of chiral ureidopropanamido derivatives as potent and selective formyl peptide receptor-2 (FPR2) agonists, that were designed starting from our lead agonist (S )-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-2-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)ureido]-N -[[1-(5-methoxy-2-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]propanamide ((S)-9a). The new compounds were obtained in overall yields considerably higher than (S)-9a. Various of the new compounds showed agonist properties comparable to that of (S)-9a along with higher selectivity over FPR1. Molecular modeling was used to define chiral recognition by FPR2. In vitro metabolic stability of selected compounds was also assessed to obtain preliminary insight on drug-like properties of this class of compounds.

Keywords: Formyl peptide receptor, ureido propanamide, chiral agonist, Ca2+ mobilization, neutrophil, metabolic stability

1. Introduction

Formyl peptide receptors (FPRs) comprise a functionally distinct G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR) subfamily. In human and other primates, three subtypes of FPRs have been identified (FPR1–3).1 FPR1 was initially reported as a high affinity receptor on the surface of neutrophils for the prototypic N-formyl peptide formyl-methionine-leucine-phenylalanine (fMLF), and its gene was cloned in 1990 from a differentiated HL-60 myeloid leukemia cell cDNA library.2,3 Two additional human FPRs, designated as FPR2 and FPR3 were subsequently cloned using the FPR1 cDNA as a probe.1 The cellular distribution of FPR1 and FPR2 in humans is largely overlapping: they have been detected in monocytes/macrophages, neutrophils, immature dendritic cells, endothelial cells, hepatocytes, astrocytes, microglial cells and fibroblasts. FPR3 is distributed in human monocytes/macrophages and dendritic cells.4 Functionally, FPRs are considered to play relevant roles in innate immunity and host defense mechanisms, including immune response to microorganism infection, proinflammatory response in amyloidogenic diseases, host responses to cell necrosis, and apoptosis.4–6 FPRs may also influence the expression and function of C-C chemokine receptor type 5 and C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 on human monocytes, two major GPCR chemokine coreceptors of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1).7,8

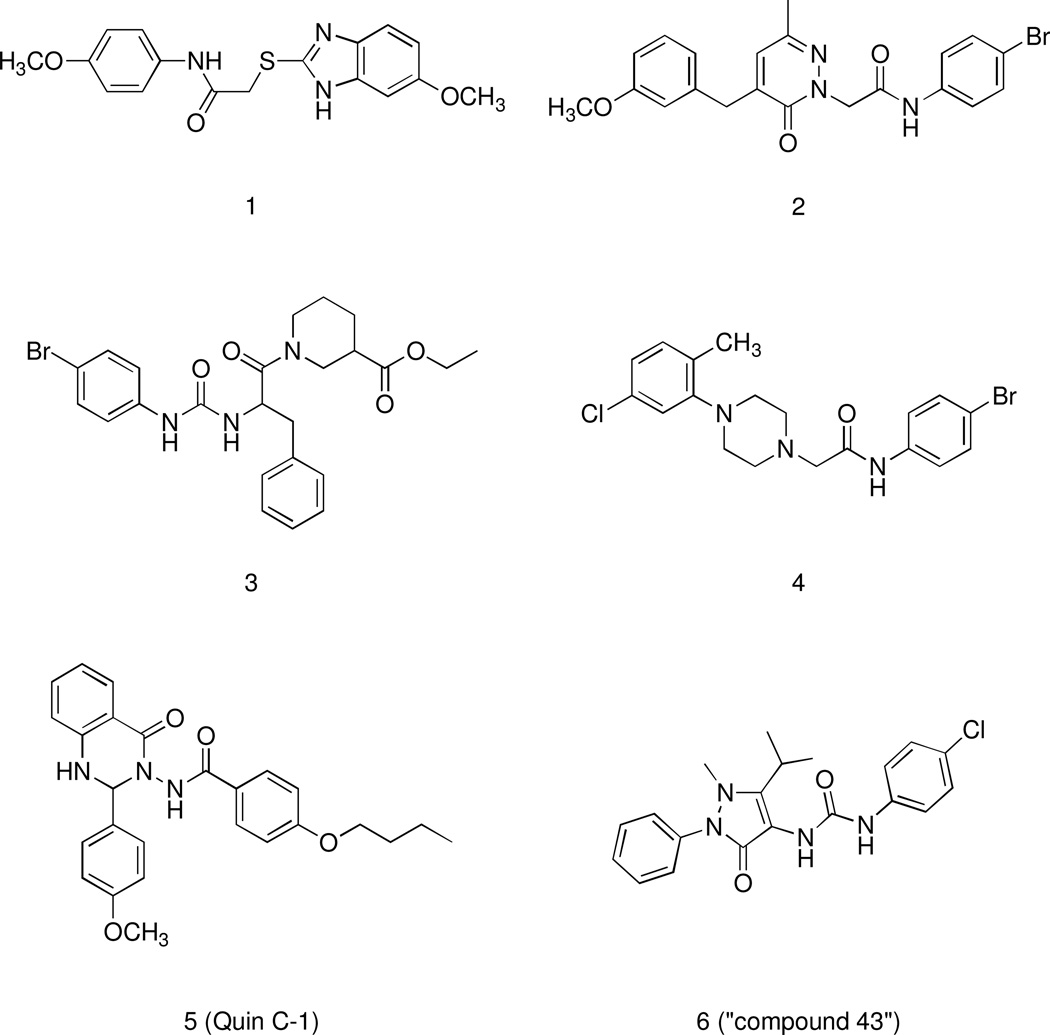

Hence, there is evidence that bioactive ligands acting as FPR agonists or antagonists might serve as useful therapeutics in host defense and as immunomodulatory activators to enhance selective innate immune responses in order to reduce detrimental effects associated with inflammation, infectious diseases, and cancer.9–13 Various endogenous and synthetic peptide FPR agonists have been used to study potential therapeutic efficacy in models of pathological processes.14 However, peptides are difficult to administer as therapeutic agents due to poor tissue penetration, serum resistance, oral bioavailability and quick elimination, making small-molecule compounds a better choice for future clinical development.15 Thus, the availability of non-peptide small-molecule FPR ligands is clearly of substantial benefit in drug development and facilitating structure-activity relationship analysis to model ligand binding features. To this end, a number of synthetic nonpeptide FPR agonists and antagonists with a wide range of chemical diversity have been identified (for a recent review see ref. 14). They include (Figure 1): benzimidazole derivatives exemplified by compound 1,16 pyridazin-3(2H)-ones (compound 2),17 N-phenylurea derivatives (compound 3),18 2-(N-piperazinyl)acetamide derivatives (compound 4),16 quinazolinones derivatives such as the highly specific non-peptide FPR2 agonist 5 (designated in most publications as Quin-C1),19 pyrazolone derivatives as the mixed FPR1/FPR2 agonist 6 (designated in most of publications as “Compound 43”).20,21

Figure 1.

Structural Formulas of Non-Peptidic FPR1/FPR2 Agonists

Despite the increased number of FPR agonists and antagonists discovered in recent years, pharmacokinetic analysis has been reported only for a limited number of compounds. Researchers at Astra Zeneca have recently published three lead optimization studies on selective FPR1 antagonists.22–24 The authors were able to identify only three selective FPR1 antagonists endowed with rat microsome intrinsic clearance (CLint) lower than 30 µL/min/mg, which was selected as lead selection criteria for in vitro metabolic stability. These studies emphasized that it was challenging to improve FPR1 potency while maintaining preferential pharmacokinetic properties.

As for FPR agonists, the only available data are related to the agonist 6, which showed relatively low clearance (0.126 L/h/kg) and a half-life of 2.78 h after iv administration to rats (0.5 mg/kg).20 Therefore, considering that compound 6 is a mixed FPR1/FPR2 agonist, it is of interest to identify selective FPR2 agonists endowed with pharmacokinetic properties suitable for studies in vivo.

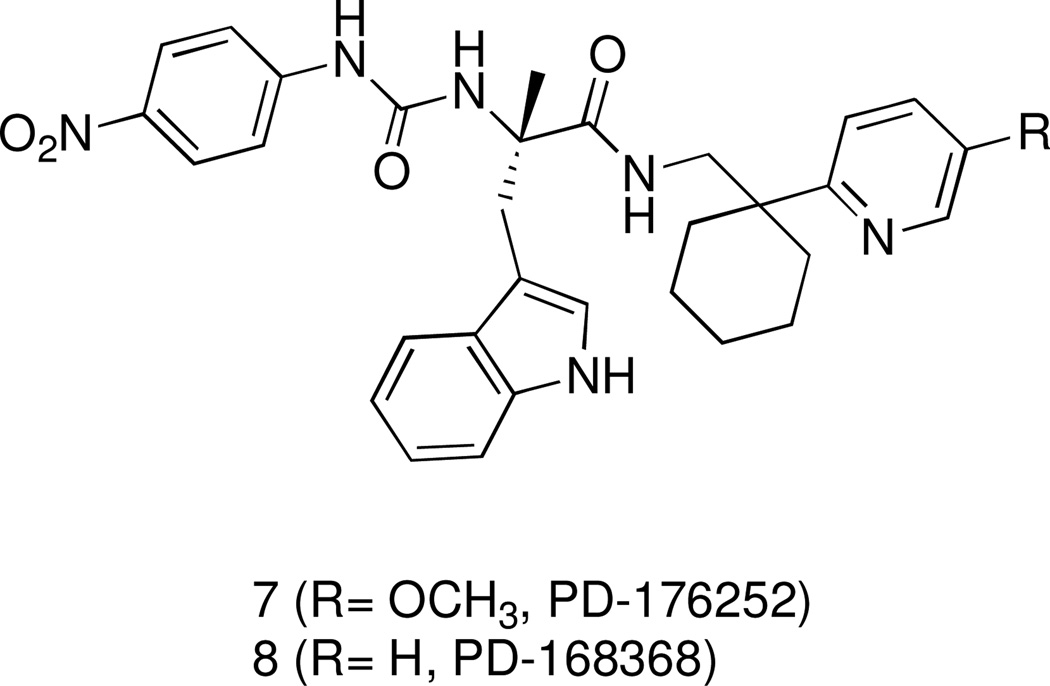

Recently, we have reported the identification of a group of 3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-2-[3-(4-nitrophenyl)ureido]propanamide as agonists of human FPR1 and/or FPR2.25 These studies originated from the finding that antagonists of gastrin-releasing peptide/neuromedin B receptors (bombesin receptors), namely PD-176252 (7), PD168368 (8) (Figure 2), and related chiral derivatives, were potent FPR1/FPR2 agonists.18 We evaluated 22 structural derivatives of compound 7 for their ability to activate human neutrophils and HL-60 cells transfected with human FPR1 or FPR2. While none of the compounds had affinity for bombesin receptors, 15 of the compounds stimulated Ca2+ flux in FPR1/FPR2 transfected cells. Among these agonists, (S)-9a (ST-12) (Table 1) emerged because it demonstrated potent agonist properties in both FPR2-HL60 cells and in human and murine neutrophils. However, the synthetic procedure for this compound greatly limited its availability in amounts compatible with in vivo studies. To overcome this limitation, and to increase our understanding of the use of such class of compounds as pharmacological tool to study FPR2 in vitro and in vivo, we designed and synthesized a set of close analogues of (S)-9 that could be obtained from easily accessible synthons. The new compounds were tested for their ability to activate FPR2 in FPR2-HL60 cells and neutrophils from humans and mice. Moreover, selected agonists were also assessed for their metabolic stability in vitro after incubation with rat microsomes in comparison with compound 7, which is known to be active in vivo.26

Figure 2.

Structural Formulas of the Bombesin-Related Receptor BB1 and BB2 antagonists PD-176252 (7) and PD-168368 (8)

Table 1.

Effect of the compounds on Ca2+ mobilization in FPR1/FPR2 transfected cells, human and mouse neutrophils

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compound | FPR1 | FPR2 | Human PMN (w/o probenecid) |

Human PMN (with probenecid) |

Mouse PMN |

| EC50, µM (Efficacy, %) | |||||

| (S)-9a | 0.43 ± 0.13 (130) |

0.096 ± 0.027 (120) |

0.064 ± 0.026 (100) |

0.060 ± 0.021 (105) |

0.24 ± 0.07 (110) |

| (R)-9a | N.A. | 0.23 ± 0.083 (100) |

0.92 ± 0.28 (40) |

0.88 ± 0.25 (95) |

4.9 ± 1.4 (30) |

| (S)-9b | N.A. | 1.6 ± 0.36 (115) |

12.6 ± 3.7 (55) |

0.66 ± 0.18 (130) |

1.7 ± 0.44 (50) |

| (R)-9b | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 2.3 ± 0.73 (65) |

| (S)-9c | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 2.5 ± 0.61 (60) |

| (R)-9c | N.A. | 0.26 ± 0.064 (65) |

N.A. | 0.97 ± 0.34 (40) |

3.8 ± 1.3 (35) |

| (S)-9d | N.A. | 0.73 ± 0.23 (75) |

1.8 ± 0.42 (30) |

0.27 ± 0.082 (105) |

3.9 ± 1.5 (75) |

| (R)-9d | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 2.1 ± 0.58 (80) |

| (S)-9e | 0.95 ± 0.26 (115) |

0.43 ± 0.11 (135) |

1.8 ± 0.37 (85) |

0.45 ± 0.13 (120) |

2.8 ± 0.64 (80) |

| (R)-9e | N.A. | 0.31 ± 0.092 (90) |

0.62 ± 0.24 (40) |

0.49 ± 0.16 (115) |

1.0 ± 0.27 (55) |

| (S)-9f | N.A. | 0.86 ± 0.21 (40) |

N.A. | 1.1 ± 0.36 (55) |

2.3 ± 0.35 (25) |

| (R)-9f | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | N.A. | 2.5 ± 0.42 (25) |

2. Chemistry

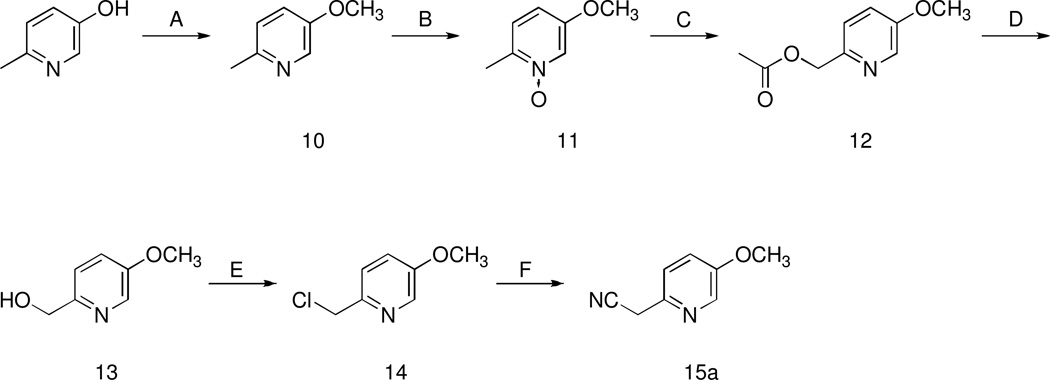

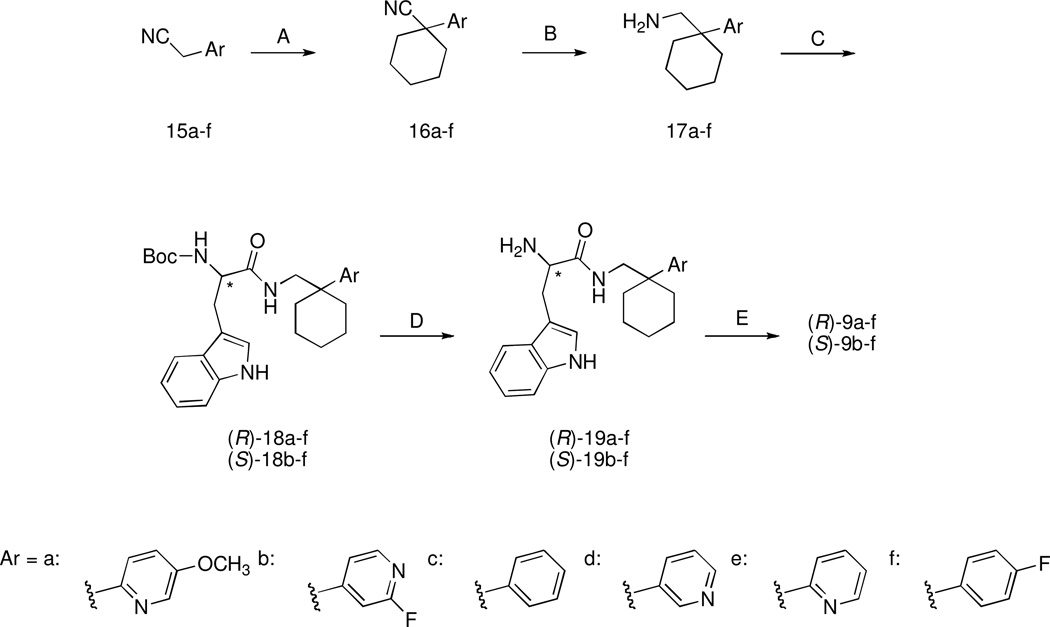

The target compounds were synthesized following the same synthetic route as our reference compound (S)-9a. The synthesis of this compound starts from the key aryl-acetonitrile derivative 15a, which can be prepared following the six-step synthetic procedure depicted in Scheme 1. 2-Methyl-5-hydroxypyridine is reacted with methyl iodide in the presence of NaH to give the methoxy derivative 10, which was subjected to oxidation with 3-chloroperbenzoic acid to give N-oxide 11. Reaction of 11 with acetic anhydride gave the ester 12, which was subsequently hydrolized with KOH to give the alcohol 13. This intermediate was then transformed into the corresponding chloroderivative 14 by means of thionyl chloride. Compound 14 underwent nucleophilic substitution by cyanide ion to give the desired aryl-acetonitrile derivative 15a. The aryl-acetonitriles 15c–f which were starting compounds for synthesis of the target compounds (S)-9c–f and (R)-9c–f (Scheme 2) were readily available from commercial sources. The aryl-acetonitrile 15b was prepared in a one-step procedure from the commercially available 2-fluoro-4-methylpyridine as previously described.27 The synthesis of the target compounds (S)-9b–f and (R)-9a–f was accomplished as follows: aryl-acetonitriles 15a–f were cyclized with 1,5-dibromopentane in the presence of NaH to give derivatives 16a–f that, after reduction with Raney nickel under hydrogen pressure yielded the amines 17a–f (Scheme 2). (R)-Boc- or (S)-Boc-tryptophan were then activated with carbonyldiimidazole and condensed with amines 17a–f to obtain the Boc-protected derivatives (R)-18a–f and (S)-18b–f. Subsequently, these latter compounds were deprotected with trifluoroacetic acid to obtain amines (R)-19-a-f and (S)-19-b-f. These intermediates were then condensed with 4-methoxyphenylisocyanate to obtain the target compounds (R)-9-a-f and (S)-9-b-f.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of Derivative 15aa

aReagents: (A) NaH (60% oil dispersion), methyl iodide; (B) 3-chloroperbenzoic acid, Na2SO4; (C) acetic anhydride; (D) KOH, MeOH; (E) SOCl2; (F) KCN.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the Target Compoundsa

aReagents: (A) NaH (60% oil dispersion), 1,5-dibromopentane; (B) Raney-nickel, H2 (5 atm), 2M ethanolic NH3; (C) (R)- or (S)-Boc-tryptophan activated with N, N’-carbonyldiimidazole; (D) trifluoroacetic acid; (E) 4-methoxyphenylisocyanate.

3. Results and discussion

The aim of the present study was to identify FPR1/FPR2 agonists with a profile similar to that of (S)-9a but more synthetically accessible, since its availability in a gram scale is limited. Consequently, the availability of (S)-9a in a gram scale is also limited. This forced us to evaluate possible substitutes of the 5-methoxy-2-pyridinyl ring in (S)-9a. Therefore, we searched for commercially available or easily accessible analogs of the key intermediate 15a, and eventually selected compounds 15b–f.

We systematically evaluated the enantiomeric pairs of target compounds (R)-9-b-f and (S)-9-b-f (Table 1) because we found in our previous study that FPR1 and FPR2 were able to discriminate between the enantiomers.25,28 For comparative purposes, we also synthesized (R)-9a which was not studied previously. As can be seen from the data in Table 1, (S)-9a was 2.4-fold more potent than (R)-9a for activating FPR2 in FPR2-HL60 cells, whereas a more pronounced difference in potency was found between these enantiomers in activation of human neutrophils (> 14-fold). Removal of the methoxy group from the pyridyl ring of compounds (S)-9a and (R)-9a gave compounds (S)-9e and (R)-9e, respectively. This modification had no significant impact on the ability of the agonists to activate Ca2+ mobilization in FPR2-HL60 cells and in human neutrophils. In contrast, in the case of 3-pyridyl positional isomers (S)-9d and (R)-9d, a marked enantioselectivity was observed: while (S)-9d was able to activate FPR2 in FPR2-HL60 cells and in human neutrophils, the (R)- enantiomer was not. A similar trend was observed for the enantiomer pairs (S)-9b/(R)-9b and (S)-9f/(R)-9f where the (S)- isomer was active and the (R)- enantiomer was inactive. Conversely, in the case of the enantiomer pairs of phenyl derivative 9c only the (R)-enantiomer was active.

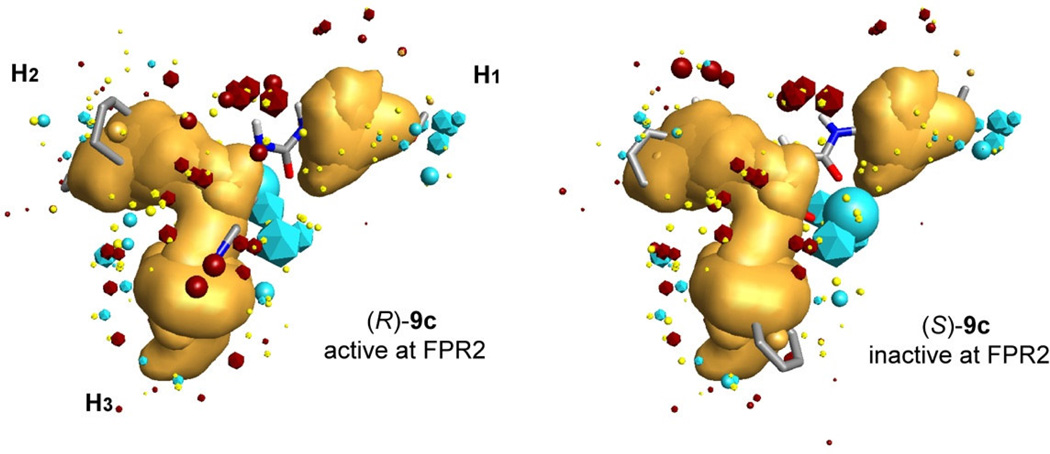

Collectively, these data confirm the ability of FPR2 to discriminate between the enantiomers. To further investigate the enantiomer preference of our FPR2 ligands, all molecules were overlaid on a previously refined three-subpocket pharmacophore model.18 The highest-score superimpositions together with values of calculated similarity are shown in Table 2. The similarity values depend equally on geometric and field similarity of a molecule and template. These field descriptors (or field points) are extrema of electrostatic, steric and hydrophobic fields.29 Similar to our previous finding,18,25 the active enantiomers of the ureidopropanamides reported here [(S)-9b, (R)-9c, (S)-9d, and (S)-9f)] had better alignments than their corresponding inactive enantiomeric conterparts. As examples, overlay of molecular conformations of the enantiomer pair (R)- and (S)-9c is shown in Figure 3. Likewise, enantiomer (S)-9a with higher activity at FPR2 also had also better aligment in comparison-with its relatively low-active counterpart (R)-9a.

Table 2.

Location of substituents from representative conformations obtained for the FPR2 Field Point pharmacophore template in hypothetical hydrophobic subpockets and alignments on this template of enantiomeric FPR2 agonists.

| Compd | Enant iomer |

FPR2 (EC50, µM)a |

Sim. | Submolecule | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subpocket I | Subpocket II | Subpocket III | ||||

| 9a | S | 0.096 | 0.609 | 4-methoxyphenyl | 1-(4-methoxyphenyl)- cyclohexyl |

3-indolyl |

| R | 0.23 | 0.553 | 4-methoxyphenyl | 3-indolyl | 1-(4-methoxyphenyl)- cyclohexyl |

|

| 9b | S | 1.6 | 0.618 | 4-methoxyphenyl | 3-indolyl | 1-(2-fluoro-4-pyridyl)- cyclohexyl |

| R | N.A. | 0.603 | 4-methoxyphenyl | 3-indolyl | 1-(2-fluoro-4-pyridyl)- cyclohexyl |

|

| 9c | S | N.A. | 0.561 | 4-methoxyphenyl | 3-indolyl | 1-phenylcyclohexyl |

| R | 0.26 | 0.576 | 4-methoxyphenyl | 1-phenylcyclohexyl | 3-indolyl | |

| 9d | S | 0.73 | 0.600 | 4-methoxyphenyl | 3-indolyl | 1-(3-pyridyl) cyclohexyl |

| R | N.A. | 0.593 | 4-methoxyphenyl | 3-indolyl | 1-(3-pyridyl) cyclohexyl |

|

| 9e | S | 0.43 | 0.656 | 4-methoxyphenyl | 3-indolyl | 1-(2-pyridyl) cyclohexyl |

| R | 0.31 | 0.595 | 4-methoxyphenyl | 3-indolyl | 1-(2-pyridyl) cyclohexyl |

|

| 9f | S | 0.86 | 0.616 | 4-methoxyphenyl | 3-indolyl | 1-(4-fluorophenyl) cyclohexyl |

| R | N.A. | 0.594 | 4-methoxyphenyl | 1-(4-fluorophenyl) cyclohexyl |

3-indolyl | |

Potency of compounds were used as reported in the present work (see Table 1).

Similarity (Sim.) between aligned molecule and the template was calculated using the FieldAlign program. Highest values of the similarity, which correlate with agonistic activity at FPR2 are in bold.

Subpockets I, II, and III in the notation of our previously published pharmacophore model.18

Figure 3.

Overlay of molecular conformations of enantiomer pair (R)-9c/(S)-9c with the best fit to the geometry of the FPR2 template. Superimpositions of the conformations to the template were refined by the simplex optimization algorithm incorporated in FieldAlign. Field points are colored as follows: blue, electron-rich (negative); red, electron-deficient (positive); yellow, van der Waals attractive (steric). All field points belonging to FPR templates are icosaedre shaped, and field points, belonging to (R)-9c/(S)-9c are spherical. The hydrophobic field surface is colored in orange. The three hydrophobic surfaces are marked as H1, H2, and H3 in accordance with our previously reported FPR2 pharmacophore model.

We previuosly reported that the substituted phenyl ring attached to the carbamide nitrogen atom is always located in subpocked I.25 The present study is consistent with this observation: the 4-methoxyphenyl group linked to the carbamide fragment occupies subpocked I of the pharmacophore model for all compounds 9a–f. We also found that subpocket II is usually occupied by a non-polar moiety of the active FPR2 enantiomer if such a moiety is present in a molecule.25 In compounds 9a–f, possible moieties for location in subpockets II and III are represented by 3-indolyl heterocycle and phenyl- or pyridyl-substituted cyclohexyl. Pyridyl and 3-indolyl fragments possess polar nitrogen centers. The phenyl ring in most cases is also modified by polar methoxy group or fluorine atom (Table 2). Thus, a non-polar moiety (1-phenylcyclohexyl) is present only in enantiomers 9c. Among these enantiomers, the active agonist (R)-9c has the non-polar fragment in subpocket II similarly to compounds investigated previously.25

According to chirality of the molecules investigated, the two fragments alternate between subpockets II and III within enantiomeric pairs 9a, 9c, and 9f. Obviously, this is conditioned by the chiral nature of the template itself. However, due to the high flexibility of molecular fragments, both enantiomers in pairs 9b and 9d have similar locations of indolyl and aryl-cyclohexyl moieties in subpockets II and III (Table 2), in spite of mutually inverse configurations of the chiral center. However, R-enantiomers in these pairs were inactive. On the other hand, the same location of these moieties in pair 9e is accompanied by relatively high agonist activity of both S- and R-enantiomers (Table 2). A visual inspection of superimpositions of these molecules on the pharmacophore template shows that active compounds have a specific orientation of the C=O group linked directly to the chiral center. For active S-enantiomers, this carbonyl group is oriented towards 3-indolyl in subpocket II, resulting in the appearance of a large blue field point between the C=O and 3-indolyl moieties. For inactive R-enantiomers, the carbonyl group is oriented “outside” the template, and the negative field point appears in another area. Nevertheless, for compound (R)-9e this carbonyl group is also directed towards 3-indolyl (not shown). We suggest that such an orientation stipulates a high activity of enantiomer (R)-9e, in spite of a lower total similarity value as compared with (S)-9e (Table 2).

All FPR2 agonists listed in Table 1 were able to induce Ca2+ mobilization in human neutrophils, except for (R)-9c and (S)-9f which were able to induce Ca2+ mobilization only in the presence of probenecid. This particular feature had been already observed in the case of two analogues of (S)-9a, which presented a nitro or a cyano group instead of the methoxy group on the phenyl ring. Probenecid is an anion exchange protein inhibitor used for slowing dye leakage from cells.30,31 The reason for the selective sensitivity of the Ca2+ flux response to probenecid for some of these chiral ureidopropanamides is unclear. Literature data indicate that probenecid is a non-specific inhibitor of multidrug resistance-associated proteins and can have different effects on several other cellular targets, including transient receptor potential V2 (TRPV2) and various nonselective cation channels.31 In addition, it has been proposed that primary myeloid cells maintain a subpopulation of FPR in a low-affinity, possibly G protein-free state,32 which is not a feature of FPR-transfected HL-60 cells. Because allosteric communication between the ligand-binding orthosteric site and the cytoplasmic G-protein-binding surface is a fundamental feature of GPCRs,33 we suggest that some FPR2 agonists with ureidopropanamide structure could stabilize this receptor in a G-protein-free state, and additional agents (e.g., probenecid) may be required to reactivate G-protein coupling.

As far as the activity on FPR1-HL60 cells is concerned, both (S)-9a and (S)-9e stimulated Ca2+ mobilization, whereas the corresponding enantiomers (R)-9a and (R)-9e were inactive. (S)-9b, (R)-9c, (S)-9d, (R)-9e, and (S)-9f were also unable to stimulate Ca2+ mobilization in FPR1-HL60 cells, thus revealing an interesting preference for FPR2, at least in FPR-transfected HL60 cells. Considering that (S)-9e was different from (S)-9d and (S)-9b only in the substitution pattern of the pyridyl ring, it is apparent that minimal structural changes can deeply influence the activity of these ureidopropanamides.

All compounds under investigation were active in mouse neutrophils, including compounds (R)-9b, (S)-9c, (R)-9d, (R)-9f, which were not able to induce Ca2+ mobilization in human neutrophils. The reason for this activity is currently not understood; however, we and others have observed quite different response patterns to some agonists and/or antagonists in human and murine neutrophils.14

Overall, the data presented here indicate that suitable structural modifications of reference compound (S)-9a led to the identification of moderately potent FPR2 agonists that can be obtained in gram scale quantity and could be possible candidates for studying in vivo effects of FPR2 activation.

Metabolic stability plays an important role in the success of drug candidates. First-pass metabolism is one of the major causes of poor bioavailability and short half-life. Until recently, metabolic stability was evaluated at a later stage of drug discovery and required laborious manual manipulations. Instead, early screening of pharmacokinetic properties provides valuable and timely information for medicinal chemists to optimize drug-like properties in parallel with activity optimization. Typically, liver microsomes are used to screen the primary form of metabolic instability resulting from phase I oxidation. Among the studied compounds, we selected two pairs of enantiomers for stability analysis, namely (R)- and (S)-9a and (R)- and (S)-9e because they were the most promising agonists of the set. These compounds were evaluated for their in vitro metabolic stability after incubation with rat microsomes, in the presence of an NADPH-generating system, in comparison with compound 7 (Figure 1). Compound 7 was selected as a reference because it is a close structural analog of (R)- 9a, (S)-9a, (R)-9e, and (S)-9e, and because it is known to be active in vivo.26 The results (Table 3) indicated that compounds (R)- and (S)-9a and (R)- and (S)-9e were rapidly metabolized by rat liver microsomes. Compounds (R)- and (S)-9e showed t1/2 = 0.6 min and (R)- and (S)-9a showed t1/2 = 1.1 and 1.2 min, respectively. Compound 7 showed a slightly higher stability in this assay with t1/2 = 4.4 min. The difference in metabolic stability between (S)-9a and 7 could be due to the presence of the nitro group in 4-position of the phenyl ring, in place of the methoxy group, which deactivates the aromatic ring with respect to hydroxylation. In addition, the presence of the α-methyl on the amide bond is likely to shield this bond from metabolic degradation. In general, these results suggest a poor pharmacokinetic profile for compounds (R)-and (S)-9a and (R)- and (S)-9e, as well as for reference compound 7. On the other hand, compound 7 is known to be active in vivo in various behavioral tests after i.p. administration in the rat and guinea pig.26 One possible explanation is that in vivo binding of compound 7 to plasma protein or tissues is high. High plasma protein binding remarkably decreases first pass metabolism of the compound in the liver since it is only the free fraction that can be metabolized.34 Due to the close similarity between the FPR1/FPR2 agonists (R)- and (S)-9a and (R)- and (S)-9b and compound 7 it is likely that these compounds share a common metabolic fate in vivo. Nevertheless, further pharmacokinetic studies are needed to fully elucidate the usability of these FPR2 agonists in vivo.

Table 3.

Stability of Selected Compounds and 7 (PD-176252) after Incubation with Rat Microsomes

| Compound | t1/2 (min) | CLint (µL/min/mg) |

|---|---|---|

| (S)-9a | 1.1 | 1162.4 |

| (R)-9a | 1.2 | 1290.6 |

| (R)-9e | 0.6 | 2476.0 |

| (S)-9e | 0.6 | 2173.4 |

| 7 (PD-176252) | 4.4 | 314.1 |

4. Conclusions

In summary, we have manipulated the structure of (S)-9a, a potent ureidopropanamide FPR agonist previously studied in our laboratories, with the aim of identifying new potent FPR agonists that can be synthesized starting from easily accessible synthons. We succeeded in our goal because we identified various FPR2 agonists with good potencies and high selectivity over FPR1 receptor. All studied compounds were overlaid to a previously refined pharmacophore model showing interaction with the FPR2 receptor similar to that of the previously reported ureidopropanamide derivatives. Finally, we have evaluated the in vitro metabolic stability of (R)- and ( S )-9 a and (R)-and (S)-9e in order to gain preliminary information on the bioavailabity and drug-like properties of these class of ligands. The tested compounds were rapidly metabolized by rat liver microsomes showing an in vitro profile comparable to that of 7 (PD-176252), a ureidopropanamide derivative that was selected as reference compound. While the metabolic stability data in vitro of (R)-and (S)-9a and (R)-and (S)-9e were quite disappointing, the notion that compound 7 is in vivo active in several animal models leaves room for further investigations of the pharmacokinetic properties of our FPR2 agonists. In any case, further structural modifications of the ureidopropanamide framework aimed to improve drug-like properties are warranted.

5. Experimental Section

5.1. Chemistry

Chemicals were purchased from Acros, Fluka, Sigma-Aldrich. Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals were used without further purification. Thin layer chromatography (TLC) was performed using plates from Merck (silica gel 60 F254). Column chromatography was performed with 1:30 Merck silica gel 60A (63–200 µm) as the stationary phase. 1H NMR (300 MHz) and 13C NMR (75 MHz) spectra were recorded on a Varian Mercury-VX spectrometer. All spectra were recorded on free bases. All chemical shift values are reported in ppm (δ). For enantiomeric pairs, NMR spectra for both enantiomers were recorded but the NMR spectrum of only one enatiomer is reported in the experimental section. Recording of mass spectra was done on an HP6890-5973 MSD gas chromatograph/mass spectrometer; only significant m/z peaks, with their percentage of relative intensity in parentheses, are reported. All spectra were in accordance with the assigned structures. HRMS-ESI analyses were performed on a Bruker Daltonics MicrOTOF-Q II mass spectrometer, mass range 50–800 m/z, electrospray ion source in positive ion mode. Elemental analyses (C,H,N) of the target compounds were performed on a Eurovector Euro EA 3000 analyzer. Analyses indicated by the symbols of the elements were within ± 0.4 % of the theoretical values. The purity of the target compounds listed in Table 1 was assessed by RP-HPLC and combustion analysis. All compounds showed ≥ 95% purity. RP-HPLC analysis was performed on a Perkin-Elmer series 200 LC instrument using a Phenomenex Prodigy ODS-3 RP-18 column, (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm particle size) and equipped with a Perkin-Elmer 785A UV/VIS detector setting λ= 254 nm. All target compounds (Table 1) were eluted with CH3OH/H2O/Et3N, 8:2:0.01 at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Enantiomeric purity of the target compounds (R)- and (S)-9a–f was assessed by chiral HPLC analysis on a Perkin-Elmer series 200 LC instrument using a Daicel ChiralCell OD column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm particle size) and equipped with a Perkin-Elmer 785A UV/VIS detector setting λ= 230 nm. The compounds were eluted with n-hexane/EtOH, 4:1, v/v at a flow rate of 0.8 mL/min. All compounds showed enantiomeric excesses (e.e.) >95%. 4-Cyanomethyl-2-fluoropyridine (15b) was prepared as described in the literature.27

5.1.1. 2-Methyl-5-methoxypyridine (10)

To a stirred suspension of NaH (60% dispersed in oil) (1.47 g, 36.8 mmol) in DMF (50 mL) at 0 °C under argon a solution of 5-hydroxy-2-methylpyridine (4.00 g, 36.7 mmol) in DMF (20 mL) was addeed slowly, then the reaction mixture was allowed to warm at room temperature. Methyl iodide (5.21 g, 36.7 mmol) was added to the reaction mixture which was stirred for 1 h. The reaction mixture was quenched by addition of isopropanol (20 mL), followed by H2O (20 mL) under argon. The reaction mixture was taken up in AcOEt and washed with aqueous NaHCO3, dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated in vacuo to give compound 10 as a pure liquid (2.40 g, 53% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 2.49 (s, 3H), 3.83 (s, 3H), 7.05–7.16 (m, 2H), 8.19 (d, 1H, J= 2.8 Hz); GC/MS m/z 124 (M++1, 9) 123 (M+, 100), 108 (71), 80 (43).

5.1.2. 2-Methyl-5-methoxypyridine-N-oxide (11)

To a solution of di 2-methyl-5-methoxypyridine (10) (2.40 g, 19.5 mmol) in CH2Cl2 was added Na2SO4 (4.15 g, 29.25 mmol) followed by 3-chloroperbenzoic acid (10.06 g, 58.3 mmol) and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for about 48 h. The reaction mixture was filtered, and the white solid was washed with CH2Cl2. The filtrate was concentrated and purified by colum chromatography (CHCl3/MeOH, 19:1, as the eluent) to give compound 11 (0.92 g, 34% yield). 1H NMR: δ 2.45 (s, 3H), 3.81 (s, 3H), 6.84 (dd, 1H, J= 2.5, 8.8 Hz), 7.13 (d, 1H, J= 8.5 Hz), 8.10 (d, 1H, J= 2.5 Hz).

5.1.3. 2-Acetoxymethyl-5-methoxypyridine (12)

A mixture of compound 11 (1.10 g, 7.9 mmol) and acetic anhydride (5 mL) was warmed to reflux for 10 min. The reaction mixture was allowed to cool to room temperature before being taken up in AcOEt, washed with aqueous NaHCO3. The separated organic layer was dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated in vacuo to give a crude residue that was chromatographed (CHCl3 as eluent). Compound 12 was obtained as a pale yellow oil (1.40 g, 98% yield). 1H NMR: δ 2.21 (s, 3H), 3.85 (s, 3 H), 5.28 (s, 2H), 7.19 (dd, 2H, J= 3.0, J= 8.5 Hz), 7.29 (d, 1H, J= 8.5 Hz), 8.28 (d, 1H, J= 2.7 Hz). GC/MS m/z 182 (M++1, 1) 181 (M+, 7), 138 (100).

5.1.4. 5-Methoxy-2-pyridinylmethanol (13)

To a solution of compound 12 (1.40 g, 7.7 mmol) in MeOH (30 mL) was added an excess of KOH and the mixture was refluxed 2 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo, and the residue was partitioned between CH2Cl2 (20 mL) and H2O (20 mL). The separated organic phase was dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated in vacuo to give compound 13 as a pale yellow oil (1.00 g, 93% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.82 (s, 1H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 4.70 (s, 2H), 7.18–7.24 (m, 2H), 8.25 (1H, J= 2.8 Hz); GC/MS m/z 140 (M++1, 3) 139 (M+, 44), 138 (100), 110 (71).

5.1.5. 2-Chloromethyl-5-methoxypyridine (14)

To a solution of compound 13 (0.90 g, 6.5 mmoli) in CH2Cl2 was added dropwise excess SOCl2 (2 mL), and the mixture was refluxed for 2 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo, and the residue was taken up in AcOEt and washed with aqueous NaHCO3. The separated organic layer was dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated in vacuo. Compound 14 was obtained as a pale yellow oil in quantitative yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 3.87 (s, 3H), 4.65 (s, 2H), 7.21 (dd, 1H, J= 2.8, 8.4 Hz), 7.39 (d, 1H, J= 8.4 Hz), 8.27 (1H, d, J= 2.8 Hz); GC/MS m/z 159 (M++2, 9) 157 (M+, 28), 122 (100).

5.1.6. 5-Methoxy-2-pyridinylacetonitrile (15a)

A mixture of derivative 14 (1.00 g, 6.3 mmol) and KCN (0.41 g, 6.3 mmol) in EtOH (30 mL) and H2O (5 mL) was refluxed overnight. The mixture was diluted with H2O (30 mL) and extracted with AcOEt (3 × 30 mL). The combined organic layers were dried Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The crude residue was purified by colum chromatography (CH2Cl2 as eluent) to give compound 15a as a yellow oil (0.37 g, 40% yield). 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 3.87 (s, 3H), 3.88 (s, 2H), 7.22 (dd, 1H, J= 3.2, 8.8 Hz), 7.34 (dd, 1H, J= 0.4, 8.4 Hz), 8.27 (1H, d, J= 2.8 Hz); GC/MS m/z 149 (M++1, 10) 148 (M+, 100), 133 (85), 105 (36), 78 (32).

5.2. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Compounds 16a–f

To a stirred suspension of NaH (60% dispersed in oil) (0.14 g, 3.4 mmol) in DMSO (20 mL) under nitrogen at 15 °C, a solution of the appropriate acetonitrile (1.8 mmol) and 1,5-dibromopentane (0.41 g, 1.8 mmol) in Et2O (4 mL) and DMSO (1 mL) was added dropwise over 1 h. The mixture was allowed to warm to room temperature and stirred for an additional 24 h under nitrogen. The reaction mixture was carefully quenched by the addition dropwise of isopropanol (5 mL), followed by H2O 5 mL) 10 min later. The mixture was diluted with AcOEt and washed with H2O. The aqueous layer was re-extracted with AcOEt, and the two organic layers were combined, dried (Na2SO4), and concentrated in vacuo. The crude residue was chromatographed (n-hexane/AcOEt, 4:1, as eluent) to give the desired compound as a colorless oil.

5.2.1. 1-(5-Methoxy-2-pyridinyl)cyclohexanecarbonitrile (16a)

30% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.76–2.12 (m, 10H), 3.87 (s, 3H), 4.65 (s, 2H), 7.21 (dd, 1H, J= 2.8, 8.8 Hz), 7.51 (dd, 1H, J= 0.8, 9.6 Hz), 8.29 (1H, d, J= 3.2 Hz); GC/MS m/z 217 (M++1, 6), 216 (M+, 34), 176 (63), 161 (100).

5.2.2. 1-(2-Fluoro-4-pyridinyl)cyclohexanecarbonitrile (16b)

51% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.26–1.32 (m, 1H), 1.70–1.90 (m, 7H), 2.14 (app d, 2H), 7.05 (d, 1H, J= 1.4 Hz), 7.31 (dt, 1H, J= 2.3, 1.7 Hz), 8.25 (d, 1H, J= 5.5 Hz). GC/MS m/z 205 (M++1, 7), 204 (M+, 49), 149 (100).

5.2.3. 1-Phenylcyclohexanecarbonitrile (16c)

37% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.23–1.31 (m, 1H), 1.73–1.89 (m, 7H), 2.13–2.17 (m, 2H), 7.29–7.42 (m, 3H), 7.47–7.51 (m, 2H). GC/MS m/z 186 (M++1, 7), 185 (M+, 47), 130 (24), 129 (100).

5.2.4. 1-(3-Pyridinyl)cyclohexanecarbonitrile (16d)

81% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.28–1.40 (m, 1H), 1.77–1.90 (m, 7H), 1.97–2.16 (m, 2H), 7.30–7.35 (m, 1H), 7.61–7.64 (m, 1H), 8.45 (dd, 1H, J= 4.7, 1.4 Hz), 8.53 (dd, 1H, J= 2.5, 0.8 Hz). GC/MS m/z 187 (M++1, 15), 186 (M+, 94), 171 (26), 131 (97), 130 (100).

5.2.5. 1-(2-Pyridinyl)cyclohexanecarbonitrile (16e)

74% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.28–1.40 (m, 1H), 1.77–1.90 (m, 7H), 1.97–2.16 (m, 2H), 7.21–7.25 (m, 1H), 7.59 (dt, 1H, J= 8.0, 1.0 Hz), 7.71 (td, 1H, J= 8.0, 1.9 Hz), 8.59–8.61 (m, 1H). GC/MS m/z 186 (M++1, 75), 185 (M+, 97), 157 (94), 146 (45), 131 (100).

5.2.6. 1-(4-Fluorophenyl)cyclohexanecarbonitrile (16f)

61% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.23–1.31 (m, 1H), 1.73–1.89 (m, 7H), 2.12–2.16 (m, 2H), 7.04–7.11 (m, 2H), 7.42–7.49 (m, 2H). GC/MS m/z 204 (M++1, 5), 204 (M+, 36), 147 (100).

5.3. General Procedure for the Synthesis of the Amines 17a–f

Raney nickel was activated with 10 M KOH, then washed with H2O, then with EtOH to remove H2O. The Raney nickel was taken up in 2 N ethanolic ammonia and the appropriate nitrile 16a–f (0.87 mmol) was added to the mixture which was then hydrogenated in autoclave under 5 bar pressure of hydrogen at 50 °C for 15 h. The reaction mixture was filtered through Celite and concentrated in vacuo to give the desired amine as a clear oil.

5.3.1. [1-(4-Methoxy-2-pyridyl)cyclohexyl]methanamine (17a)

90% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.14–1.55 (m, 10H, 2H D2O exchanged), 2.23–2.28 (m, 2H), 2.79 (s, 2H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 7.31 (d, 1H, J= 8.0 Hz), 7.64 (td, 1H, J= 8.0, 1.9 Hz), 8.60–8.62 (m, 1H). GC/MS m/z 221 (M++1, 0.5), 191 (100), 162 (26), 123 (18).

5.3.2. [1-(2-Fluoro-4-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methanamine (17b)

91% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.18–1.37 (m, 4H), 1.52–1.65 (m, 6H), 2.10 (app d, 2H), 2.73 (s, 2H), 7.05 (d, 1H, J= 1.4 Hz), 7.31 (dt, 1H, J= 2.3, 1.7 Hz), 8.25 (d, 1H, J= 5.5 Hz). ESI+/MS m/z 209 (M+H)+, ESI-MS/MS m/z 192 (100).

5.3.3. (1-Phenylcyclohexyl)methanamine (17c)

73% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.14 (s, 2H, D2O exchanged), 1.35–1.41 (m, 3H), 1.44–1.55 (m, 5H), 2.11–2.15 (m, 2H), 2.68 (s, 2H), 7.18–7.23 (m, 1H), 7.31–7.38 (m, 4H). GC/MS m/z 172 (0.2), 159 (52), 158 (100), 117 (26), 91 (91).

5.3.4. [1-(3-Pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methanamine (17d)

86% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.14 (s, 2H, D2O exchanged), 1.35–1.41 (m, 3H), 1.44–1.55 (m, 5H), 2.11–2.15 (m, 2H), 2.68 (s, 2H), 7.30–7.35 (m, 1H), 7.61–7.64 (m, 1H), 8.45 (dd, 1H, J= 4.7, 1.4 Hz), 8.53 (dd, 1H, J= 2.5, 0.8 Hz). GC/MS m/z 186 (96), 171 (26), 130 (100).

5.3.5. [1-(2-Pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methanamine (17e)

87% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.14–1.55 (m, 10H, 2H D2O exchanged), 2.23–2.28 (m, 2H), 2.79 (s, 2H), 7.08–7.12 (m, 1H), 7.31 (d, 1H, J= 8.0 Hz), 7.64 (td, 1H, J= 8.0, 1.9 Hz), 8.60–8.62 (m, 1H). GC/MS m/z 173 (11), 161 (100), 132 (50).

5.3.6. [1-(4-Fluorophenyl)cyclohexyl]methanamine (17f)

84% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.14–1.52 (m, 8H, 2H D2O exchanged), 1.66–1.88 (m, 2H), 2.05–2.17 (m, 2H), 2.67 (s, 2H), 7.00–7.10 (m, 2H), 7.26–7.31 (m, 1H), 7.48–7.48 (m, 1H). GC/MS m/z 176 (40), 135 (15), 109 (100).

5.4. General Procedure for the Synthesis of BOC-Protected Derivatives (R)-18a–f and (S)-18b–f

N, N’-carbonyldiimidazole (1.1 mmol) was added to a solution of (1.0 mmol), in anhydrous THF (10 mL), under N2. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight, then a solution of the appropriate amine (1.0 mmol) in anhydrous THF was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 6 h. The solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue was partitioned between EtOAc (20 mL) and H2O (20 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with EtOAc (2 × 20 mL) and the collected organic layers were dried (Na2SO4) and evaporated in vacuo. The crude residue was chromatographed (CHCl3/EtOAc, 7:3, as eluent) to give pure target compound as a white solid.

5.4.1. (R)-1-(1H-Indol-3-ylmethyl)-2-[[[1-(5-methoxy-2-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]amino]-2-oxoethyl]carbamic acid, 1,1-dimethylethyl ester ((R)-18a)

35% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.20–1.50 (m, 15H), 1.71–1.75 (m, 2H), 1.87–1.94 (m, 2H), 3.06–3.14 (m, 1H), 3.22–3.29 (m, 3H), 3.80 (s, 3H), 4.37–4.39 (m, 1H), 5.14–5.17 (m, 1H), 6.33 (br s, 1H), 6.84–6.87 (m, 1H), 6.91–6.99 (m, 2H), 7.11 (t, 1H, J= 7.4 Hz), 7.19 (t, 1H, J= 7.3 Hz), 7.33 (d, 1H, J= 8.0 Hz), 7.63 (d, 1H, J= 7.7 Hz), 8.01 (br s, 1H), 8.07 (br s, 1H). ESI/MS m/z 505 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 431 (100), 302 (61).

5.4.2. (R)-2-[[[1-(2-Fluoro-4-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]amino]-2-oxoethyl]-1-(1H-Indol-3-ylmethyl)-carbamic acid, 1,1-dimethylethyl ester ((R)-18b)

12% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.23–1.50 (m, 15H), 1.62–1.65 (m, 2H), 1.81–1.87 (m, 2H), 3.06–3.14 (m, 2H), 3.19–3.32 (m, 2H), 4.27–4.35 (m, 1H), 5.06 (br s, 1H), 5.35 (t, 1H, J= 2.9 Hz), 6.66 (dd, 1H, J= 8.5, 3.0 Hz), 6.96 (d, 1H, J= 1.9 Hz), 7.11–7.25 (m, 3H), 7.37 (d, 1H, J= 8.0 Hz), 7.61 (d, 1H, J= 7.5 Hz), 7.85 (s, 1H), 8.18 (s, 1H). ESI/MS m/z 493 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 419 (66), 289 (100).

5.4.3. (S)-2-[[[1-(2-Fluoro-4-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]amino]-2-oxoethyl]-1-(1H-Indol-3-ylmethyl)-carbamic acid, 1,1-dimethylethyl ester ((S)-18b)

43% Yield. ESI/MS m/z 493 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 494 (13), 493 (100), 419 (9).

5.4.4. (R)-1-(1H-Indol-3-ylmethyl)-2-[[(1-phenylcyclohexyl)methyl]amino]-2-oxoethyl]carbamic acid, 1,1-dimethylethyl ester ((R)-18c)

61% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.23–1.50 (m, 15H), 1.52–1.60 (m, 2H), 1.84–1.90 (m, 2H), 3.01–3.11 (m, 2H), 3.02–3.64 (m, 2H), 4.29–4.31 (m, 1H), 5.04 (br s, 1H), 5.18 (br s, 1H), 6.96 (d, 1H, J= 1.9 Hz), 7.12–7.14 (m, 5H), 7.36 (d, 1H, J= 8.2 Hz), 7.62 (d, 1H, J= 7.7 Hz), 8.05 (s, 1H). ESI/MS m/z 474 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 401 (26), 400 (100), 271 (87).

5.4.5. (S)-1-(1H-Indol-3-ylmethyl)-2-[[(1-phenylcyclohexyl)methyl]amino]-2-oxoethyl]carbamic acid, 1,1-dimethylethyl ester ((S)-18c)

60% Yield. ESI/MS m/z 474 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 401 (28), 400 (100), 271 (92).

5.4.6. (R)-1-(1H-Indol-3-ylmethyl)-2-[[[1-(3-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]amino]-2-oxoethyl]carbamic acid, 1,1-dimethylethyl ester ((R)-18d)

83% Yield. ESI/MS m/z 475 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 401 (87), 272 (100).

5.4.7. (S)-1-(1H-Indol-3-ylmethyl)-2-[[[1-(3-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]amino]-2-oxoethyl]carbamic acid, 1,1-dimethylethyl ester ((S)-18d)

68% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.18–1.49 (m, 15H), 1.58–1.61 (m, 2H), 1.85–1.90 (m, 2H), 3.04–3.14 (m, 1H), 3.04–3.44 (m, 1H), 3.20–3.25 (m, 1H), 3.29–3.36 (m, 1H), 4.29–4.31 (m, 1H), 5.08 (br s, 1H), 5.32 (br s, 1H), 6.93 (d, 1H, J= 2.2 Hz), 7.03–7.24 (m, 4H), 7.36 (d, 1H, J= 8.0 Hz), 7.62 (d, 1H, J= 8.0 Hz), 8.25 (s, 1H), 8.31 (d, 1H, J= 1.7 Hz), 8.38 (dd, 1H, J= 4.7, 1.7 Hz). ESI/MS m/z 475 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 401 (82), 272 (100).

5.4.8. (R)-1-(1H-Indol-3-ylmethyl)-2-[[[1-(2-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]amino]-2-oxoethyl]carbamic acid, 1,1-dimethylethyl ester ((R)-18e)

28% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.30–1.50 (m, 17H), 1.72–1.85 (m, 1H), 1.89–2.00 (m, 1H), 3.11 (dd, 1H, J= 14.4, 7.6 Hz), 3.25 (dd, 1H, J= 14.3, 5.2 Hz), 3.30 (d, 2H, J= 5.5 Hz), 4.39 (br s, 1H), 5.12 (br s, 1H), 6.44 (br s, 1H), 6.95–7.05 (m, 3H), 7.12 (dt, 1H, J= 7.0, 1.1 Hz), 7.19 (dt, 1H, J= 7.0, 1.1 Hz), 7.33 (d, 1H, J= 8.0 Hz), 7.49 (br t, 1H), 7.63 (d, 1H, J= 8.0 Hz), 8.01 (br s, 1H), 8.33 (br s, 1H). ESI-MS m/z 475 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 401 (100), 272 (62).

5.4.9. (S)-1-(1H-Indol-3-ylmethyl)-2-[[[1-(2-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]amino]-2-oxoethyl]carbamic acid, 1,1-dimethylethyl ester ((S)-18e)

92% Yield. ESI/MS m/z 475 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 401 (100), 272 (94).

5.4.10. (R)-2-[[[1-(4-Fluorophenyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]amino]-2-oxoethyl]-1-(1H-Indol-3-ylmethyl)-carbamic acid, 1,1-dimethylethyl ester ((R)-18f)

78% Yield 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.20–1.48 (m, 15H), 1.55–1.62 (m, 2H), 1.72–1.85 (m, 2H), 2.99–3.11 (m, 2H), 3.21–3.31 (m, 2H), 4.30–4.32 (m, 1H), 5.04 (br s, 1H), 5.16 (br s, 1H), 6.80 (app d, 3H), 6.97 (d, 1H, J= 2.2 Hz), 7.13–7.24 (m, 3H), 7.37 (d, 1H, J= 7.9 Hz), 7.63 (d, 1H, J= 7.7 Hz), 8.07 (s, 1H). ESI/MS m/z 492 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 418 (89), 289 (100).

5.4.11. (S)-2-[[[1-(4-Fluorophenyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]amino]-2-oxoethyl]-1-(1H-Indol-3-ylmethyl)-carbamic acid, 1,1-dimethylethyl ester ((S)-18f)

63% Yield. ESI/MS m/z 492 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 418 (100), 289 (49).

5.5. General Procedure for the Synthesis of Amines (R)-19a–f and (S)-19b–f

Trifluoroacetic acid (5 mL) was added to a solution of (R)-18a–f, (S)-18b–f (0.46 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (20 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 h and basified with aqueous 1M NaOH. The separated aquous phase was extracted with CHCl3 (2 × 20 mL). The combined organic layers were dried (Na2SO4) and concentrated in vacuo to give the desired compounds as pale yellow semisolids.

5.5.1. (R)-2-Amino-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-N-[[1-(5-methoxy-2-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]propanamide ((R)-19a)

96% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.22–1.58 (m, 10H), 2.07–2.12 (m, 2H), 2.81 (dd, 1H, J= 14.0, 9.0 Hz), 3.29 (dd, 1H, J= 12.0, 3.8 Hz), 3.41 (d, 2H, J= 6.1 Hz), 3.62 (dd, 1H, J= 9.0, 4.2 Hz), 3.83 (s, 3H), 7.02 (d, 1H, J= 2.2 Hz), 7.11–7.22 (m, 4H), 7.29–7.37 (m, 2H), 7.65 (d, 1H, J= 7.7 Hz), 8.12 (br s, 1H), 8.24 (d, 1H, J= 2.5 Hz). ESI/MS m/z 405 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 405 (14), 216 (100), 205 (85), 188 (51).

5.5.2. (R)-2-Amino-N-[[(1-(2-fluoro-4-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)propanamide ((R)-19b)

90% Yield. ESI/MS m/z 392 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 263 (100), 177 (65).

5.5.3. (S)-2-Amino-N-[[(1-(2-fluoro-4-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)propanamide ((S)-19b)

Quantitative yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.23–1.50 (m, 10H), 1.62–1.65 (m, 2H), 1.81–1.87 (m, 2H), 3.06–3.14 (m, 2H), 3.19–3.32 (m, 2H), 4.27–4.35 (m, 1H), 6.66 (dd, 1H, J= 8.5, 3.0 Hz), 6.96 (d, 1H, J= 1.9 Hz), 7.11–7.25 (m, 2H), 7.37 (d, 1H, J= 8.0 Hz), 7.61 (d, 1H, J= 7.5 Hz), 7.85 (s, 1H), 8.18 (s, 1H). ESI/MS m/z 392 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 263 (100), 177 (54).

5.5.4. (R)-2-Amino-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-N-[(1-phenylcyclohexyl)methyl]propanamide ((R)-19c)

93% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.23–1.70 (m, 10H), 1.98–2.05 (m, 2H), 2.82 (dd, 1H, J= 14.3, 8.5 Hz), 3.25–3.35 (m, 3H), 3.60 (dd, 1H, J= 8.3, 4.4 Hz), 6.84 (br t, 1H), 7.00–7.01 (m, 1H), 7.10–7.38 (m, 8H), 7.63–7.66 (m, 1H), 8.08 (br s, 1H). ESI/MS m/z 374 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 242 (100), 130 (62).

5.5.5. (S)-2-Amino-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-N-[(1-phenylcyclohexyl)methyl]propanamide ((S)-19c)

98% Yield. ESI/MS m/z 374 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 242 (100), 130 (71).

5.5.6. (R)-2-Amino-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-N-[[1-(3-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]propanamide ((R)-19d)

97% Yield. ESI/MS m/z 375 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 246 (100), 244 (57), 214 (50), 160 (65).

5.5.7. (S)-2-Amino-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-N-[[1-(3-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]propanamide ((S)-19d)

Quantitative yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.25–1.70 (m, 10H), 2.00–2.07 (m, 2H), 2.82 (dd, 1H, J= 14.4, 8.7 Hz), 3.23–3.44 (m, 3H), 3.61 (dd, 1H, J= 8.7, 4.1 Hz), 6.97 (d, 1H, J= 1.9 Hz), 7.06–7.30 (m, 3H), 7.36 (dd, 1H, J= 8.1, 0.7 Hz), 7.53–7.57 (m, 2H), 7.63 (d, 1H, J= 7.7 Hz), 8.24 (br s, 1H), 8.45 (dd, 1H, J= 4.7, 1.4 Hz), 8.53 (dd, 1H, J= 2.5, 0.8 Hz). ESI/MS m/z 375 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 246 (100), 244 (58), 214 (52), 160 (70).

5.5.8. (R)-2-Amino-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-N-[[1-(2-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]propanamide ((R)-19e)

98% Yield. ESI/MS m/z 375 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 244 (18), 214 (100), 160 (33).

5.5.9. (S)-2-Amino-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-N-[[1-(2-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]propanamide ((S)-19e)

97% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.25–1.54 (m, 10H), 2.04–2.10 (m, 2H), 2.86–2.95 (m, 1H), 3.21–3.45 (m, 3H), 3.78–3.82 (m, 1H), 7.02–7.34 (m, 6H), 7.52–7.60 (m, 3H), 8.41–8.50 (m, 1H), 8.73 (br s, 1H). ESI/MS m/z 375 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 244 (18), 214 (100), 160 (33).

5.5.10. (R)-2-Amino-N-[[1-(4-fluorophenyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)propanamide (( R)-19f)

94% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.25–1.76 (m, 10H), 1.82–1.96 (m, 2H), 2.84 (dd, 1H, J= 14.3, 8.5 Hz), 3.23–3.35 (m, 3H), 3.62 (dd, 1H, J= 8.3, 4.4 Hz), 6.93 (br s, 1H), 6.95–7.24 (m, 7H), 7.35–7.38 (m, 1H), 7.63 (d, 1H, J= 7.4 Hz), 8.18 (br s, 1H). ESI/MS m/z 392 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 263 (100), 261 (42).

5.5.11. (S)-2-Amino-N-[[1-(4-fluorophenyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)propanamide ((S)-19f)

93% Yield. ESI/MS m/z 392 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 263 (100), 261 (41).

5.6. General Procedure for the Synthesis of the Final Compounds (R)-9a–f and (S)-9b–f

To a solution of the amine (R)-19a–f, (S)-19b–f (1.0 mmol) in anhydrous THF, a solution of 4-methoxyphenylisocyanate (1.2 mmol) in the same solvent (10 mL) was added and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 5 h (TLC monitoring, CHCl3:AcOEt, 1:1 as the eluent). After removing the solvent in vacuo, the residue was taken up in CHCl3 (20 mL) and washed with H2O (2 × 20 mL). The separated organic layer was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude residue was chromatographed (CHCl3:AcOEt, 1:1 as the eluent). When necessary, the obtained solid was further purified by crystallization from EtOAc/petroleum ether to give the final compounds as a pale yellow powders.

5.6.1. (R)-3-(1H-Indol-3-yl)-2-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)ureido]-N-[[1-(5-methoxy-2-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]propanamide ((R)-9a)

54% Yield. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 1.18–1.46 (m, 9H), 1.64–1.75 (m, 1H), 1.92–1.94 (m, 1H), 3.10 (dd, 1H, J= 14.3, 8.2 Hz), 3.07–3.31 (m, 2H), 3.75 (s, 3H), 3.77 (s, 3H), 4.62–4.69 (m, 1H), 6.02 (d, 1H, J= 7.7 Hz), 6.47 (t, 1H, J= 5.1 Hz), 6.73–6.82 (m, 3H), 6.84–6.96 (m, 2H), 7.04–7.25 (m, 5H), 7.26–7.31 (m, 1H), 7.63 (d, 1H, J= 7.7 Hz), 8.00 (d, 1H, J= 3.0 Hz), 8.10 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (CDCl3): 22.3, 26.3, 29.4, 33.2, 33.8, 43.2, 49.1, 55.0, 55.2, 55.6, 55.8, 111.0, 114.5, 119.2, 119.3, 119.8, 121.7, 122.2, 122.7, 123.4, 123.5, 127.7, 132.1, 136.1, 136.4, 153.9, 155.9, 156.1, 156.2, 172.7, 111.0, 111.3, 114.5, 119.2, 119.3, 119.8, 121.7, 122.2, 122.7, 123.4, 123.5. ESI/MS m/z 554 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 431 (100), 504 (33), 302 (6). Compound melted at 119–121 °C (from n-hexane/CHCl3). Anal. (C32H37N5O4) C, H, N.

5.6.2. (R)-N-[[(1-(2-Fluoro-4-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-2-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)ureido]propanamide ((R)-9b)

23% Yield. ESI/MS m/z 542 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 419 (91), 393 (100). Compound melted at 240–242 °C (from n-hexane/CHCl3). Anal. (C31H34FN5O3) C, H, N.

5.6.3. (S)-N-[[(1-(2-Fluoro-4-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-2-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)ureido]propanamide ((S)-9b)

48% Yield. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 1.07–1.56 (m, 9H), 1.84–1.88 (m, 1H), 1.99–2.04 (m, 1H), 2.76 (dd, 1H, J= 14.6, 8.0 Hz), 2.91 (dd, 1H, J= 14.7, 5.6 Hz), 3.00 (dd, 1H, 13.4, 5.7 Hz), 3.66 (s, 3H), 4.42 (q, 1H, J= 7.2 Hz), 6.11 (d, 1H, J= 8.0 Hz), 6.75–6.80 (m, 3H), 6.86 (dd, 1H, J= 8.5, 3.0 Hz), 6.95 (t, 1H, J= 7.0 Hz), 7.01–7.24 (m, 2H), 7.18–7.24 (m, 2H), 7.30 (d, 1H, J= 8.0 Hz), 7.51 (d, 1H, J= 7.7 Hz), 7.60–7.68 (m, 2H), 8.08 (s, 1H), 8.37 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): 26.9, 31.2, 34.2, 38.2, 46.7, 54.8, 58.9, 60.4, 60.5, 60.6, 111.4, 119.3, 123.6, 124.4, 124.7, 126.3, 129.0, 132.8, 138.9, 141.5, 143.1, 159.3, 160.2, 165.2, 168.3, 177.7. ESI/MS m/z 542 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 419 (91), 393 (100). Compound melted at 230–232 °C (from n-hexane/CHCl3). Anal. (C31H34FN5O3) C, H, N.

5.6.4. (R)-3-(1H-Indol-3-yl)-2-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)ureido]-N-[(1-phenylcyclohexyl)methyl]propanamide ((R)-9c)

40% Yield. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 1.11–1.46 (m, 9H), 1.87–2.01 (m, 2H), 2.79–3.00 (m, 3H), 3.67 (s, 3H), 4.44 (q, 1H, J= 4.4 Hz), 6.11 (d, 1H, J= 8.0 Hz), 6.78 (d, 2H, J= 9.1 Hz), 6.95 (t, 1H, J= 7.3 Hz), 7.01–7.24 (m, 10H), 7.30 (d, 2H, J= 7.7 Hz), 7.51 (d, 1H, J= 7.7 Hz), 8.41 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): 22.4, 26.5, 29.3, 33.1, 33.5, 43.2, 50.7, 54.2, 55.7, 55.9, 110.6, 111.8, 112.0, 114.6, 118.8, 118.9, 119.2, 119.3, 119.7, 119.9, 121.5, 124.1, 124.3, 126.2, 127.4, 127.6, 128.1, 129.0. ESI/MS m/z 523 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 400 (100), 374 (56). Compound melted at 159–161 °C (from n-hexane/CHCl3). Anal. (C32H36N4O3) C, H, N.

5.6.5. (S)-3-(1H-Indol-3-yl)-2-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)ureido]-N-[(1-phenylcyclohexyl)methyl]propanamide ((S)-9c)

44% Yield. ESI/MS m/z 523 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 400 (100), 374 (52). Compound melted at 161–163 °C (from n-hexane/CHCl3). Anal. (C32H36N4O3) C, H, N.

5.6.6. (R)-3-(1H-Indol-3-yl)-2-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)ureido]-N-[[1-(3-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]propanamide ((R)-9d)

85% Yield. 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): 22.3, 26.4, 29.4, 33.1, 42.3, 50.2, 54.1, 55.7, 55.9, 110.6, 114.6, 118.8, 119.3, 119.7, 119.9, 124.0, 124.2, 128.1, 134.2, 135.5, 135.6, 136.7, 140.1, 147.4, 149.3, 149.5, 154.6, 155.5, 173.0. ESI/MS m/z 524 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 401 (100), 375 (96). Compound melted at 208–210 °C (from n-hexane/CHCl3). Anal. (C31H35N5O3) C, H, N.

5.6.7. (S)-3-(1H-Indol-3-yl)-2-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)ureido]-N-[[1-(3-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]propanamide ((S)-9d)

67% Yield. 1H NMR (CDCl3): δ 1.171.46 (m, 9H), 1.70–1.75 (m, 1H), 1.87–1.93 (m, 1H), 3.05–3.19 (m, 2H), 3.30 (dd, 1H, J= 13.5, 6.9 Hz), 3.75 (s, 3H), 4.60 (q, 1H, J= 7.2 Hz), 5.83 (d, 1H, J= 7.4 Hz), 6.06 (t, 1H, J= 6.2 Hz), 6.70–6.76 (m, 2H), 6.83 (d, 1H, J= 2.2 Hz), 6.98–6.11 (m, 3H), 7.16–7.35 (m, 5H), 7.58 (d, 1H, J= 3.0 Hz), 8.25–8.28 (m, 2H), 8.38 (s, 1H); ESI/MS m/z 524 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 401 (100), 375 (96). Compound melted at 204–206 °C (from n-hexane/CHCl3). Anal. (C31H35N5O3) C, H, N.

5.6.8. (R)-3-(1H-Indol-3-yl)-2-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)ureido]-N-[[1-(2-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]propanamide ((R)-9e)

46% Yield. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 1.08–1.47 (m, 9H), 2.02–2.06 (m, 1H), 2.13–2.17 (m, 1H), 2.83 (dd, 1H, J= 14.8, 7.1 Hz), 2.96–3.09 (m, 2H), 3.66 (s, 3H), 4.43 (q, 1H, J= 7.1 Hz), 6.12 (d, 1H, J= 8.0 Hz), 6.74–6.80 (m, 3H), 6.97 (dt, 1H, J= 7.7, 0.8 Hz), 7.00–7.11 (m, 3H), 7.17–7.23 (m, 3H), 7.29 (d, 1H, J= 8.0 Hz), 7.50–7.57 (m, 3H), 8.41 (s, 1H), 8.46 (dd, 1H, J= 4.7, 1.1 Hz); ESI/MS m/z 524 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 402 (30), 401 (100), 375 (44). Compound melted at 128–131 °C (from n-hexane/CHCl3). Anal. (C31H35N5O3) C, H, N.

5.6.9. (S)-3-(1H-Indol-3-yl)-2-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)ureido]-N-[[1-(2-pyridinyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]propanamide ((S)-9e)

72% Yield. 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): 22.6, 26.4, 29.3, 32.9, 33.0, 45.7, 49.2, 54.1, 55.7, 55.8, 11.6, 111.9, 114.6, 118.9, 119.3, 119.8, 121.5, 122.2, 124.2, 128.1, 134.4, 136.8, 149.4, 154.6, 155.6, 155.5, 164.3, 172.8. ESI/MS m/z 524 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 401 (100), 375 (49). Compound melted at 175–178 °C (from n-hexane/CHCl3). Anal. (C31H35N5O3) C, H, N.

5.6.10. (R)-N-[[1-(4-Fluorophenyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-2-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)ureido]propanamide ((R)-9f)

53% Yield. 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 1.16–1.56 (m, 10H), 1.84–1.88 (m, 1H), 2.92 (dd, 1H, J= 13.2, 5.0 Hz), 3.05–3.24 (m, 1H), 3.31 (dd, 1H, J=13.2, 7.4 Hz), 3.77 (s, 3H), 4.12 (q, 1H, J= 7.2 Hz), 6.71–6.79 (m, 7H), 6.90 (s, 1H), 7.08–7.14 (m, 3H), 7.19–7.25 (m, 3H), 7.35 (d, 1H, J= 8.0 Hz), 7.63 (d, 1H, J= 7.7 Hz), 8.11 (s, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6): 22.3, 26.5, 29.3, 33.3, 33.7, 42.8, 54.2, 55.7, 55.9, 110.6, 114.6, 115.2, 115.5, 118.9, 119.7, 119.8, 128.1, 129.5, 134.2, 136.8, 140.9, 154.6, 155.5, 159.3, 162.6, 172.8. ESI/MS m/z 541 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 418 (100), 392 (70). Compound melted at 109–112 °C (from n-hexane/CHCl3). Anal. (C32H35FN4O3) C, H, N.

5.6.11. (S)-N-[[1-(4-Fluorophenyl)cyclohexyl]methyl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-2-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)ureido]propanamide ((S)-9f)

40% Yield. ESI/MS m/z 541 (M-H)−, ESI-MS/MS m/z 418 (100), 392 (63). Compound melted at 219–221 °C (from n-hexane/CHCl3). Anal. (C32H35FN4O3) C, H, N.

5.7. Biological assays

5.7.1. Cell culture

Human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 cells stably transfected with FPR1 (HL-60-FPR1) or FPR2 (HL-60-FPR2) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 10 mM HEPES, 100 lg/mL streptomycin, 100 U/mL penicillin, and G418 (1 mg/mL), as previously described.35 Wild type HL-60 cells were cultured under the same conditions, but without G418.

5.7.2. Neutrophil isolation

Blood was collected from healthy donors in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board at Montana State University. Neutrophils were purified from the blood using dextran sedimentation, followed by Histopaque 1077 gradient separation and hypotonic lysis of red blood cells, as previously described.36 Isolated neutrophils were washed twice and resuspended in HBSS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ (HBSS−). Neutrophil preparations were routinely >95% pure, as determined by light microscopy, and >98% viable, as determined by trypan blue exclusion.

For murine neutrophil isolation, bone marrow leukocytes were flushed from tibias and femurs of BALB/c mice with HBSS, filtered through a 70-µm nylon cell strainer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) to remove cell clumps and bone particles, and resuspended in HBSS at 106 cells/ml. Bone marrow neutrophils were isolated from bone marrow leukocyte preparations, as described previously.37 In brief, bone marrow leukocytes were resuspended in 3 ml of 45% Percoll solution and layered on top of a Percoll gradient consisting of 2 ml each of 50, 55, 62, and 81% Percoll solutions in a conical 15-ml polypropylene tube. The gradient was centrifuged at 1600g for 30 min at 10°C, and the cell band located between the 62 and 81% Percoll layers was collected. The cells were washed, layered on top of 3 ml of Histopaque 1119, and centrifuged at 1600g for 30 min at 10°C to remove contaminating red blood cells. The purified neutrophils were collected, washed, and resuspended in HBSS. All animal use was conducted in accordance with a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Montana State University.

5.7.3. Ca2+ mobilization assay

Changes in intracellular Ca2+ were measured with a FlexStation II scanning fluorometer using a FLIPR 3 calcium assay kit (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) for human neutrophils and HL-60 cells, as described previously.16 All active compounds were evaluated in parent (wild-type) HL-60 cells for supporting that the agonists are inactive in non-transfected cells. Human neutrophils or HL-60 cells, suspended in HBSS- containing 10 mM HEPES, were loaded with Fluo-4 AM dye (Invitrogen) (1.25 µg/mL final concentration) and incubated for 30 min in the dark at 37 °C. After dye loading, the cells were washed with HBSS− containing 10 mM HEPES, resuspended in HBSS containing 10 mM HEPES and Ca2+ and Mg2+ (HBSS+), and aliquotted into the wells of flat-bottom, half-area-well black microtiter plates (2 × 105 cells/well). If indicated, 2 mM probenecid was added 5 min before the assay. The compound of interest was added from a source plate containing dilutions of test compounds in HBSS+, and changes in fluorescence were monitored (λex = 485 nm, λem = 538 nm) every 5 s for 240 s at room temperature after automated addition of compounds. Maximum change in fluorescence, expressed in arbitrary units over baseline, was used to determine agonist response. Responses were normalized to the response induced by 5 nM fMLF (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) for FPR1 HL-60 cells and neutrophils, or 5 nM WKYMVm (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) for FPR2 HL-60 cells, which were assigned a value of 100%. Curve fitting (5–6 points) and calculation of median effective concentration values (EC50) were performed by nonlinear regression analysis of the dose-response curves generated using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA).

5.7.4. Stability Assays in Rat Liver Microsomes

Test compounds were pre-incubated at 37 °C with rat liver microsomes (0.5 mg/mL microsomal protein) at 1 µM final concentration in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 10 min. Metabolic reactions were initiated by the addition of a NADPH regenerating system ((β-nicotinammide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, isocitric acid isocitric dehydrogenase, final isocitric dehydrogenase concentration, 1unit/mL). Aliquots were removed (0, 5, 10, 20, 30, and 60 min) and immediately mixed with an equal volume of cold acetonitrile containing internal standard (100 ng/mL tolbutamide and 100 ng/mL labetalol). Test compound incubated with microsomes without NADPH regenerating system for 60 min was included. Quenched samples were centrifugated at 4000 rpm for 20 min, and the supernatants were collected for quantification analysis.

The relative loss of parent compound over the course of the incubation was monitored by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS). LC-MS analysis was performed using a Shimadzu LC 20-AD coupled with an API 4000 mass spectometer. LC separation was achieved using a Phenomenex Synergi Hydro-RP 80A C18 (4 µm; 2.0 x 30 mm) with 0.1% formic acid in water (solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (solvent B) as eluents. Linear gradient eluition started from 100% A to 100% B within 0.8 min. The flow rate was 800 µL/min and the injection volume was 10 µL.

MS analysis was performed with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source in positive ion mode. Instrument settings: nebulizer gas, nitrogen, 2.5 bar; dry gas, nitrogen, 10 L/min; dry heater 300 °C; collision gas: argon; capillary voltage: 5500 V. Concentrations were quantified by measuring the area under the peak (M+H+) and converted to percentage of compound remaining, using t = 0 peak area value as 100%. Natural logarithm of percentage remaining versus time data for each compound was fitted to linear regression and the slope was used to calculate the degradation half-life according to the equation:38

In vitro half-life was then used to calculate the intrinsic plasma clearance (CLint) according to the following equation:38

Positive controls included testosterone (CYP3A4 substrate), propafenone (CYP2D6 substrate) and diclofenac (CYP2C9 substrate) gave the values listed below.

Testosterone: t1/2 = 1 min; CLInt = 1421.4 µL/min/mg; propafenone: t1/2 = 3.1 min; CLInt = 444.0 µL/min/mg; diclofenac: t1/2 = 8.7 min; CLInt = 159.8 µL/min/mg.

5.7.5. Molecular Modeling

FieldTemplater software was used to build a pharmacophore template on the base of five FPR2 agonists.18 The template contains field points of different types in the positions of energy extrema for probe atoms. Positive probes give “negative” field points, whereas energy extrema for negative and neutral probe atoms correspond to “positive” and steric field points, respectively. Hydrophobic field points were also generated with neutral probes capable of penetrating into the molecular core and reaching extrema in the centers of hydrophobic regions (e.g. benzene rings). The size of a field point depends on magnitude of an extremum.29 We used FieldAlign program to search for alignments of enantiomeric pairs R/S-9a–f onto the template. For the enantiomers imported into FieldAlign, conformation hunter algorithm was used to generate representative sets of conformations corresponding to local minima of energy calculated within the extended electron distribution force field.39,40 This algorithm incorporated in the FieldTemplater and FieldAlign software allowed us to obtain up to 200 independent conformations that were passed to further calculation of field points surrounding each conformation of each molecule. To decrease the number of rotatable bonds during the conformation search, the “force amides trans” option was enabled in FieldAlign. Field point calculations were performed for each conformation, as described above. Conformations with the best fit to the geometry and field points of the template were identified, and their superimpositions were refined by the simplex optimization algorithm incorporated in FieldAlign. The measure of similarity was derived from the field point spatial distribution and geometric overlap between a molecule and the template.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health IDeA Program COBRE grant GM110732, an equipment grant from the M.J. Murdock Charitable Trust, and the Montana State University Agricultural Experiment Station.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ye RD, Boulay F, Wang JM, Dahlgren C, Gerard C, Parmentier M, Serhan CN, Murphy PM. Pharmacol. Rev. 2009;61:119. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Le Y, Murphy PM, Wang JM. Trends Immunol. 2002;23:541. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(02)02316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boulay F, Tardif M, Brouchon L, Vignais P. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1990;168:1103. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)91143-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Migeotte I, Communi D, Parmentier M. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:501. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panaro MA, Acquafredda A, Sisto M, Lisi S, Maffione AB, Mitolo V. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2006;28:103. doi: 10.1080/08923970600625975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le Y, Yang Y, Cui Y, Yazawa H, Gong W, Qiu C, Wang JM. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2002;2:1. doi: 10.1016/s1567-5769(01)00150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Su SB, Gong WH, Gao JL, Shen WP, Grimm MC, Deng X, Murphy PM, Oppenheim JJ, Wang JM. Blood. 1999;93:3885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Braun MC, Wang JM, Lahey E, Rabin RL, Kelsall BL. Blood. 2001;97:3531. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang L, Falla TJ. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2009;10:164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dufton N, Perretti M. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010;127:175. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDonald B, Pittman K, Menezes GB, Hirota SA, Slaba I, Waterhouse CC, Beck PL, Muruve DA, Kubes P. Science. 2010;330:362. doi: 10.1126/science.1195491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nash N, Scully A, Gardell L, Olsson R, Gustafsson M. Patent US. 2004 60/592,926. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cevik-Aras H, Kalderen C, Jenmalm JA, Oprea T, Dahlgren C, Forsman H. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2012;83:1655. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schepetkin IA, Khlebnikov AI, Giovannoni MP, Kirpotina LN, Cilibrizzi A, Quinn MT. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014;21:1478. doi: 10.2174/0929867321666131218095521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mason JM. Future Med. Chem. 2010;2:1813. doi: 10.4155/fmc.10.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirpotina LN, Khlebnikov AI, Schepetkin IA, Ye RD, Rabiet MJ, Jutila MA, Quinn MT. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010;77:159. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.060673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cilibrizzi A, Quinn MT, Kirpotina LN, Schepetkin IA, Holderness J, Ye RD, Rabiet MJ, Biancalani C, Cesari N, Graziano A, Vergelli C, Pieretti S, Dal Piaz V, Giovannoni MP. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:5044. doi: 10.1021/jm900592h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schepetkin IA, Kirpotina LN, Khlebnikov AI, Jutila MA, Quinn MT. Mol. Pharmacol. 2011;79:77. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.068288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He M, Cheng N, Gao WW, Zhang M, Zhang YY, Ye RD, Wang MW. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2011;32:601. doi: 10.1038/aps.2011.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bürli RW, Xu H, Zou X, Muller K, Golden J, Frohn M, Adlam M, Plant MH, Wong M, McElvain M, Regal K, Viswanadhan VN, Tagari P, Hungate R. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006;16:3713. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sogawa Y, Ohyama T, Maeda H, Hirahara KJ. Pharmacol. Sci. 2011;115:63. doi: 10.1254/jphs.10194fp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morley AD, Cook A, King S, Roberts B, Lever S, Weaver R, Macdonald C, Unitt J, Fagura M, Phillips T, Lewis R, Wenlock M. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:6456. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.08.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Unitt J, Fagura M, Phillips T, King S, Perry M, Morley A, MacDonald C, Weaver R, Christie J, Barber S, Mohammed R, Paul M, Cook A, Baxter A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:2991. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morley AD, King S, Roberts B, Lever S, Teobald B, Fisher A, Cook T, Parker B, Wenlock M, Phillips C, Grime K. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:532. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.10.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schepetkin IA, Kirpotina LN, Khlebnikov AI, Leopoldo M, Lucente E, Lacivita E, De Giorgio P, Quinn MT. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013;85:404. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Merali Z, Bédard T, Andrews N, Davis B, McKnight AT, Gonzalez MI, Pritchard M, Kent P, Anisman H. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:10387. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1219-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasumi K, Ohta S, Saito T, Sato S, Kato J-Y, Sato J, Suzuki H, Asano H, Okada M, Matsumoto Y, Shirota K. Patent. 2008 WO2008001930. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cilibrizzi A, Schepetkin IA, Bartolucci G, Crocetti L, Dal Piaz V, Giovannoni MP, Graziano A, Kirpotina LN, Quinn MT, Vergelli C. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012;20:3781. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheeseright T, Mackey M, Rose S, Vinter A. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2006;46:665. doi: 10.1021/ci050357s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Abrahamse SL, Rechkemmer G. Pflugers Arch. 2001;441:529. doi: 10.1007/s004240000437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McClenaghan C, Zeng F, Verkuyl JM. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2012;10:533. doi: 10.1089/adt.2012.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prossnitz ER, Quehenberger O, Cochrane CG, Ye RD. J. Immunol. 1993;151:5704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenbaum DM, Zhang C, Lyons JA, Holl R, Aragao D, Arlow DH, Rasmussen SG, Choi HJ, Devree BT, Sunahara RK, Chae PS, Gellman SH, Dror RO, Shaw DE, Weis WI, Caffrey M, Gmeiner P, Kobilka BK. Nature. 2011;469:236. doi: 10.1038/nature09665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Damre AA, Iyer KR. The Significance and Determination of Plasma Protein Binding. Encyclopedia of Drug Metabolism and Interactions. 2012;III:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Christophe T, Karlsson A, Rabiet MJ, Boulay F, Dahlgren C. Scand. J. Immunol. 2002;56:470. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2002.01149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schepetkin IA, Kirpotina LN, Khlebnikov AI, Quinn MT. Mol. Pharmacol. 2007;71:1061. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.033100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siemsen DW, Malachowa N, Schepetkin IA, Whitney AR, Kirpotina LN, Lei B, Deleo FR, Quinn MT. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1124:19. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-845-4_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Obach RS, Baxter JG, Liston TE, Silber BM, Jones BC, MacIntyre F, Rance DJ, Wastall P. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1997;283:46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vinter JG. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 1994;8:653. doi: 10.1007/BF00124013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheeseright TJ, Mackey MD, Scoffin RA. Curr. Comput. Aided Drug Des. 2011;7:190. doi: 10.2174/157340911796504314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]