Abstract

Arrhythmic sudden cardiac death (SCD) may be due to ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation (SCD-VT/VF) or pulseless electrical activity/asystole. Effective risk stratification to identify patients at risk of arrhythmic SCD is essential for targeting our health care and research resources to tackle this important public health issue. Although our understanding of SCD due to pulseless electrical activity/asystole is growing, the overwhelming majority of research in risk stratification has focused on SCD-VT/VF. This review focuses on existing and novel risk stratification tools for SCD-VT/VF. For patients with left ventricular dysfunction and/or myocardial infarction, advances in imaging, measures of cardiac autonomic function, and measures of repolarization have shown considerable promise in refining risk. Yet the majority of SCD-VT/VF occurs in patients without known cardiac disease. Biomarkers and novel imaging techniques may provide further risk stratification in the general population beyond traditional risk stratification for coronary artery disease alone. Despite these advances, significant challenges in risk stratification remain that must be overcome before a meaningful impact on SCD can be realized.

Keywords: Sudden cardiac death-arrhythmias, risk assessment, ventricular arrhythmia

Introduction

Sudden cardiac death (SCD), generally defined as death within one hour of symptom onset or during sleep in a patient who was previously stable, is a clinical syndrome that is a final common pathway of a number of disease conditions and states. The syndrome includes arrhythmic and non-arrhythmic causes. Arrhythmic SCD may be preventable, treatable, or a terminal manifestation of severe underlying heart disease. Arrhythmic SCD may also represent either a personal or societal acceptable outcome for patients with advanced heart disease, in part responsible for the dramatic variations in per capita use of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator in different countries.1 Because of the potentially treatable arrhythmias that form a major part of this syndrome, there has been an array of research activities into approaches to identify patients at risk, preventive therapies (i.e. beta-blockers), and reactive therapies (cardiopulmonary resuscitation, implantable cardioverter-defibrillators [ICDs]). These studies have provided important insights and illustrate the multi-dimensional nature of the problem. In this article, we will review risk stratification approaches for arrhythmic SCD.

Arrhythmic SCD may be due to ventricular fibrillation (VF)/tachycardia (VT) [SCD-VT/VF] or asystole/pulseless electrical activity (PEA). Epidemiologic studies suggest that there has been a decline in cardiac arrest due to VT/VF and a concomitant increase in PEA/asystole.2 While the cause for this is unclear, at least part of the explanation lies in improved therapy for acute coronary syndromes and chronic coronary artery disease (CAD). Therapies that treat or prevent myocardial infarction (MI) have a major impact on the occurrence of SCD-VT/VF.3–5 The majority of research in risk stratification has focused on SCD-VT/VF as the pathophysiologic understanding, outcomes and available treatments for this are far superior than for PEA/asystole.6 SCD from PEA/asystole is emerging as an important focus for future investigation but risk stratification in this area is in its infancy.7 Consequently, this review focuses on risk stratification of SCD-VT/VF.

Contemporary risk stratification for SCD-VT/VF in clinical practice centers almost solely around which patients should receive implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs). This is problematic as ICDs, in their current form, are resource-intensive and not without risk, limiting their scope to those at highest risk for SCD-VT/VF, particularly in health care systems with scarce resources. Implantation of ICDs in only those at high risk also ignores the fundamental epidemiology of SCD-VT/VF. The majority of SCD-VT/VF cases occurs in patients not traditionally considered a “high risk” group and frequently, SCD-VT/VF is the first manifestation of cardiac disease.8 Major society guideline recommendations for ICD implantation are also largely based on inclusion criteria of large randomized trials that demonstrated survival benefit for ICD therapy.9, 10 Yet actual risk of SCD-VT/VF is more nuanced and dependent on multiple factors.11, 12 Therefore current guidelines may not represent optimal allocation of health resources from both a financial and population health perspective.

More accurate risk stratification is required for any meaningful impact on the population burden of SCD-VT/VF. Despite the complexity of the problem, there have been considerable recent advances in our understanding of SCD-VT/VF that show promise in enhancing our ability to identify those at risk.

2. Important concepts in risk stratification

Before discussing existing and novel methods for assessing risk, it is worthwhile to examine selected fundamental concepts in risk stratification of SCD.

The first is that risk in complex cardiac conditions with varying phenotype (i.e. ischemic heart disease) is almost never dichotomous but rather continuous, which is particularly true in the case of SCD-VT/VF. Because indications for therapy in SCD-VT/VF are often presented as dichotomous, it can be natural to presume underlying risk is also dichotomous.8 However, the risk of SCD-VT/VF is the result of a complex interaction of a number of factors that result in a continuous spectrum of risk. Furthermore, this risk is dynamic, and modulated by a variety of environmental factors as well as biorhythms (time of day, day of week, season).13, 14 In SCD-VT/VF and other complex diseases, no single variable has adequate discrimination to dichotomize risk. The notion of continuous risk has been well applied to other disease states such as coronary artery disease and cardiac surgery.15, 16 Yet the adoption of continuous risk models to SCD-VT/VF has not gained traction to date. Practice guidelines for treatment inevitably require some categorization of patient risk. Such categorization is not entirely based on underlying risk of SCD-VT/VF but is also influenced by the risk/benefit of treatment, inclusion criteria of pertinent clinical trials and cost effectiveness analyses.

Perhaps an even more important concept in SCD-VT/VF is that of competing risk. All patients at risk for SCD-VT/VF will also be at risk for non-sudden death from cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular causes. Many of the identified risk factors for SCD-VT/VF, such as functional status, intraventricular conduction delay and concomitant atrial fibrillation, are also risk factors for non-sudden death.11, 12, 17 Among patients at high risk of SCD-VT/VF, certain patients may be at very high concomitant risk of non-sudden death; in these patients, the benefit of ICD therapy might be small despite the increased risk of SCD-VT/VF. Optimal risk stratification in SCD-VT/VF would identify those patients at high risk of VT/VF but in whom the competing risk of non-sudden death is low, thereby identifying those who would benefit most from targeted intervention.

Not only is the risk of SCD-VT/VF dependent on multiple factors, but the risk of an individual can change markedly over time. Risk assessment using only a single, static assessment is likely to be inadequate for accurate long-term prediction. Individual variables frequently change over time. For example, considering only the immediate post- MI left ventricular (LV) function in risk stratification ignores the frequent improvements that occur in the first few months or the development of adverse remodeling that may occur over a period of years.18 Furthermore, the importance of certain factors in determining risk may also change over time. In both the REFINE and CARISMA studies, measures of impaired autonomic function assessed within the first month after MI were poorly predictive of SCD.19, 20 Yet these measurements became predictive when measured at 2–4 months. Thus risk assessment for SCD-VT/VF must be a dynamic process and will require periodic reassessment.21

3. Risk stratification in left ventricular dysfunction and after myocardial infarction

Myocardial infarction and LV dysfunction are the two conditions that have the highest population attributable risk for SCD-VT/VF (each >30%).22 These conditions frequently overlap and patients with either or both conditions are at high risk of SCD-VT/VF and the majority of research into risk prediction of SCD-VT/VF has focused on these populations.

The pathophysiology of the development of VT/VF in the presence of LV dysfunction and/or MI represents a complex interplay between multiple factors.23 These factors can be broadly grouped into: (1) anatomic substrate (generally fixed) abnormalities, (2) autonomic abnormalities and (3) measures of arrhythmia vulnerability (i.e. ECG repolarization abnormalities). A further approach to risk stratification aims to provoke or identify subclinical arrhythmias that may be precursors for VT/VF. Finally, the development of VT/VF is also influenced by patient-level factors (such as age, comorbidities and functional status), biorhythms (such as time of day, season), and genetic factors. The influence of genetic factors in SCD is discussed in a separate article in this compendium [reference Priori/Bezzina].

A wide range of tools has been evaluated for risk stratification and the sheer number can be daunting for the clinician and researcher alike. It is useful to classify these tools within the larger pathophysiologic framework of SCD-VT/VF and a summary is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of available risk stratification tools for SCD-VT/VF in patients with myocardial infarction and/or left ventricular dysfunction

| Domain | Technique |

|---|---|

| 1. Anatomic substrate abnormalities | |

| A) Cardiac imaging | Global left ventricular function/ejection fraction Myocardial scar assessment (MRI, SPECT, PET) ECG QRS duration |

| B) ECG depolarization abnormalities | ECG QRS fractionation Signal-averaged ECG |

| 2. Autonomic measures | Heart rate variability Heart rate turbulence Baroreceptor sensitivity Imaging – SPECT (MIBG), PET (11C-meta- hydroxyephedrine) |

| 3. ECG repolarization measures | T-wave alternans QT dispersion/variability QRS-T angle QT interval |

| 4. Provocative testing/screening for non-sustained arrhythmias | Electrophysiology study Ventricular ectopy and non-sustained VT on ambulatory ECG monitoring |

Abbreviations: MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; SPECT, single photon emission computed tomography; PET, positron emission tomography; ECG, electrocardiogram; MIBG, meta-iodobenzylguanidine; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

3.1 Methods for identifying fixed substrate abnormalities

3.1.1 Cardiac imaging

The vast majority of ventricular arrhythmias in patients with MI and/or LV dysfunction arise from diseased myocardium and particularly from regions of myocardial scar.24–26 Myocardial scar may lead to both slow and heterogeneous electrical conduction within the heart, both of which are central to the development of VT and VF. As there is no current treatment for myocardial scar, it is considered a “fixed” substrate with a persistent risk of SCD-VT/VF. Consequently, evaluation and quantification of scar, broadly defined to include the peri-infarction border zone, may provide a useful tool for risk stratification. There are limitations to the use of scar as a risk measure of for SCD-VT/VF. Not all scar is necessarily arrhythmogenic and scar itself can be heterogeneous, as outlined below. Furthermore, although scar is considered relatively “fixed,” the electrical properties of scar undoubtedly evolve over time.

A crude marker for overall scar burden is global LV systolic function, which is most frequently quantified as left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). The link between reduction in LVEF and risk of SCD-VT/VF in patients with MI and or LV dysfunction is well established.27, 28 LVEF has numerous advantages in that it can measured by a variety of means that are ubiquitously available (including echocardiography, angiography, nuclear imaging and magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) and the measurement itself is relatively easy, though susceptible to substantial differences related to technique and loading conditions, among other factors. Consequently, LVEF became the major inclusion criteria for trials evaluating ICDs for the primary prevention of SCD.29–31 The positive results of these trials directly led to the incorporation of LVEF as the major determinant of who should receive ICD therapy.9, 10

There are serious limitations to LVEF as a risk stratification tool. LVEF is a potent predictor of overall mortality and non-SCD, which limits its specificity as a predictor for SCD-VT/VF.27 As such, LVEF alone has been insufficient to predict patients who would benefit from ICD therapy post MI and after bypass surgery.32, 33 Perhaps most importantly, LVEF, as a global measure of heart function, is only loosely correlated with the amount of myocardial scar.34 As a result, the predictive ability of LVEF alone for SCD-VT/VF is modest.

A variety of imaging modalities allow for more direct imaging of scar. Echocardiography allows for indirect scar imaging through analysis of wall motion and deformation. Advances in tissue Doppler techniques, namely strain imaging, have allowed for more specific identification of scar beyond identification of wall motion abnormalities.35 In a large, multicenter, prospective study of 569 patients >40 days post MI, strain imaging provided better prediction of arrhythmic events (VT/VF) and SCD than LVEF, particularly in patients with LVEF >35%.36

Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET) can also identify scar by visualizing areas with irreversible perfusion defects. Each of these modalities has been shown to predict arrhythmic and cardiovascular death among patients with MI.37, 38 Because of their reliance on perfusion, SPECT and PET imaging may be less useful for non-ischemic causes of LV dysfunction. Yet, in patients with MI, SPECT and PET imaging can simultaneously assess scar, ischemic burden, hibernating myocardium and even autonomic function.39 Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is able to identify myocardial scar by delayed enhancement imaging after gadolinium administration. It has a much greater spatial resolution than SPECT or PET imaging and is not dependent on vascular perfusion, allowing for identification of scar in non-ischemic processes. Quantification of total scar burden by MRI has been shown to be superior to LVEF in predicting VT/VF and appropriate ICD therapy in both ischemic and non-ischemic populations. Yet simple quantification of scar burden does not fully reflect the complex pathophysiology of scar-based VT/VF. Electrophysiology mapping has revealed that most VT circuits are found in scar, with surviving islands of electrical activity.40 Thus heterogeneous scar with both dense, electrically inactive and less dense, electrically active areas may be more arrhythmogenic. Cardiac MRI is capable of differentiating heterogeneous zones, which appear as intermediate intensity delayed enhancement, from dense scar and such findings correlate well with results of electrophysiology voltage mapping of VT circuits.41 A growing number of studies have also demonstrated that the burden of heterogeneous scar is an independent predictor of VT/VF, ICD therapy and overall mortality.42–44 In fact, after accounting for heterogeneous scar burden, LVEF loses most or all of its predictive power.

The mounting body of observational evidence of the utility of scar quantification by MRI in SCD-VT/VF led to the design of the DETERMINE trial.45 This randomized study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of ICD therapy in ischemic patients with ≥10% LV scar but whose LVEF did not meet traditional criteria for ICD implant.45 Unfortunately, the trial was stopped prematurely, largely for enrollment/funding reasons. This highlights the challenges in bringing promising risk markers to evaluation in randomized trials.

3.1.2 ECG measures of depolarization

Finally, we should not forget the original cardiac imaging modality, the electrocardiogram (ECG). This simple, inexpensive tool may have a role to play in risk stratification for SCD-VT/VF. Abnormalities in depolarization, such as QRS prolongation, may result from myocardial scar. However, depolarization abnormalities may also arise from ventricular dilation or fibrosis, potentially limiting specificity. QRS duration alone is questionable as a predictor of SCD-VT/VF.46, 47 Signal-averaged ECG (SAECG) may be more sensitive in detecting late ventricular activation from areas of heterogeneous scar.48 However, the positive predictive value of an abnormal SAECG has generally been insufficient for risk prediction in patients with ischemic heart disease.49 An abnormal SAECG was incorporated in the inclusion criteria, along with an LVEF <36%, for the CABG-PATCH trial, but the combination of these two risk factors failed to identify a population that would benefit from ICD therapy.32 While SAECG may have no role in risk stratification of patients undergoing surgical revascularization, its role in other populations remains to be determined.

Fractionation or fragmentation of the QRS complex on ECG may be a more specific marker of myocardial scar and consequently may be more useful in risk stratification for SCD-VT/VF. In a cohort of 361 ICD recipients with LV dysfunction, a fragmented QRS was a strong predictor of ventricular arrhythmias whereas QRS duration was a better predictor of overall mortality.50 In patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy, fragmented QRS may be one of the strongest predictors of arrhythmic events.51 While promising, no standard definition of a “fragmented QRS” has been established and the inter and intra-rater variability has yet to be determined.

3.2 Evaluating cardiac autonomic function

The autonomic nervous system plays an integral role in the development of ventricular arrhythmias, particularly in patients with MI or LV dysfunction.52 Normal cardiac mechanical and electrical function results from a balance of sympathetic and parasympathetic tone. In the setting of cardiac disease, this balance may be disrupted; sympathoexcitation can precipitate VT/VF and parasympathetic activation can be protective. Therefore, measures of autonomic tone have been considered prime targets for risk stratification tools. The main difficulty has been to identify a measure of autonomic function with adequate discrimination for utility in predicting SCD-VT/VF.

Heart rate variability (HRV) has been the most extensively investigated measure of autonomic tone. Loss of vagal tone leads to a decrease in the spontaneous variation in heart rate and was initially described after myocardial infarction.53 Assessing the utility of HRV for the prediction of SCD-VT/VF is clouded by the numerous potential techniques used to quantify HRV. HRV can be quantified using time domain indices, frequency domain indices and nonlinear analyses.54

Diminished HRV has been associated with both SCD and non-sudden death in MI and in chronic LV dysfunction, independent of LVEF.55, 56 The poor specificity of HRV to predict SCD-VT/VF may limit its use in risk stratification. The DINAMIT study randomized patients with severely impaired LVEF and abnormal HRV after acute MI to ICD or optimal medical therapy only.33 The negative results of this trial were, in part, due to high rates of non-sudden death. At present, it is unclear whether measures of HRV can provide adequate refinement of risk of SCD-VT/VF alone.

Heart rate turbulence (HRT) has been evaluated as another, non-invasive and reproducible measure of autonomic function. HRT quantifies the short-term variation in heart rate following a spontaneous ventricular premature beat and is closely linked to baro-receptor sensitivity.57, 58 However, unlike baroreceptor sensitivity, HRT requires no intervention as it can be measured from ECG recordings alone. HRT has been shown to predict overall mortality, independent of LVEF, after MI.56, 59 However, in the REFINE study of patients after MI, HRT was also independently predictive of fatal or non-fatal cardiac arrest.19 Therefore, HRT may be more specific for SCD-VT/VF than HRV.

A recent meta-analysis in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy found that none of the evaluated autonomic markers (HRV, HRT, baroreceptor sensitivity) was predictive of SCD-VT/VF.60 ECG-based evaluation of autonomic tone may therefore not provide an adequate discriminator of risk for SCD-VT/VF. This may be due, in part, to the focus of these techniques on autonomic modulation of the sinus node rather than the disturbed autonomic function of the ventricles, the site of interest for the pathogenesis of SCD-VT/VF.

However, advances in SPECT and PET imaging can allow for visualization of cardiac sympathetic function of the left ventricle.39 Using norepinephrine analogs (such as 123I-meta-iodobenzylguanidine [MIBG], 11C-meta-hydroxyephedrine [HED]), both PET and SPECT can identify areas of relative sympathetic denervation. In the prospective PARAPET study of patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy receiving an ICD, the amount of viable, but denervated myocardium was independently predictive of the development of VT or arrhythmic death.61 Similarly, in the ADMIRE-HF study of patients with ischemic and non-ischemic LV dysfunction, SPECT assessment of global cardiac sympathetic innervation was predictive of both arrhythmic and non-arrhythmic outcomes.62

3.3 Measures of ECG repolarization

A less well characterized component of arrhythmogenesis relates to dynamic changes in the cardiac electrical system that lead to vulnerability to ventricular arrhythmias. Almost all evaluated measures of such vulnerability are markers of abnormal repolarization on ECG. A number of such ECG repolarization measures have been identified.

An abnormal corrected QT interval on a static ECG has not routinely independently correlated with mortality or arrhythmic outcomes in patients with MI or with LV dysfunction.49 Dynamic changes in the QT interval, in particular QT variability, has been associated with SCD and overall mortality. Yet the discrimination provided by QT variability is insufficient at identifying subgroups at high risk of SCD-VT/VF.63

A more promising measure of dynamic electrical substrate is microvolt T-wave alternans (TWA). TWA refers to beat-to-beat changes in repolarization and reflects heterogeneity between cells and cell layers within the myocardium. Increasing heterogeneity leads to increased risk of arrhythmia.64 TWA is a rate-dependent phenomenon that can be assessed by exercise testing or by evaluating spontaneous changes during ambulatory ECG monitoring.65 Studies evaluating the utility of TWA in risk stratification have produced mixed results. In a pre-specified substudy of SCD-HeFT, TWA was not a predictor of SCD or arrhythmic events in a chronic, mixed etiology LV dysfunction population.66 However, the REFINE study demonstrated that TWA was an independent predictor of fatal and non-fatal cardiac arrest in patients with recent MI and its discrimination was enhanced in combination with HRT.19 Similar findings were observed in a secondary analysis of TWA in the randomized MERLIN-TIMI 36 trial in patients with non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes.67 The ABCD trial also showed that TWA was predictive of SCD or ICD discharge, in combination with EP testing in those with ischemic cardiomyopathy, LVEF <40% and non-sustained VT.68 The particular combination of a negative TWA and negative EP study identified a population at “low risk” who still had a 1 year event rate of 2.3%. There are several technical aspects that may account for these discrepant results, including timing of testing, a large proportion of intermediate results, concomitant medications and outcomes used. Nonetheless, the totality of literature supports TWA as predictive of arrhythmic events.51, 69 Improvements in standardization of methods for assessment of TWA and ease of assessment could increase its penetrance into clinical practice if specific patient populations can be defined in which its predictive value is sufficient.

3.4 Provocative testing and detection of subclinical arrhythmias

Invasive electrophysiology (EP) testing in risk stratification for SCD-VT/VF has primarily consisted of programmed ventricular stimulation to assess for inducibility for sustained VT or VF. EP testing has a long history in the evaluation of drug therapy for VT and a positive EP study was a requirement for ICD implantation in initial practice guidelines. Other potentially important information can be derived at EP study, such as electroanatomic identification of scar and repolarization measures, but these have not been extensively evaluated in risk stratification. While both MADIT and MUSTT incorporated EP testing, the specific role of the EP study in risk stratification was evaluated as part of the MUSTT trial.70 Patients with ischemic LV dysfunction (LVEF <40%) and non-sustained VT underwent EP study. Those with inducible VT were randomized to antiarrhythmic/ICD therapy or standard care. The overall trial showed superiority of ICD therapy for inducible patients. However, even in non-inducible patients, the rate of cardiac arrest or SCD was 12% at 2 years. Thus the positive predictive value of EP testing is high, but the negative predictive value is modest.

The ABCD trial showed that the EP study may be more useful in combination with non-invasive testing.68 The combination of a negative TWA and negative EP study identified a low risk group with an event rate of 2.3% at 2 years in a population similar to the MUSTT population. Thus, EP testing is likely of most benefit as part of a serial testing strategy. There are also important limitations to EP testing, including limited ability to predict primary polymorphic VT or VF.

Since the advent of inpatient ECG monitoring, it has been observed that VT/VF is often preceded by non-sustained VT or frequent premature ventricular complexes (PVCs). Frequent PVCs and non-sustained VT are among the earliest established risk factors for SCD-VT/VF after MI.27, 71 The evidence supporting risk associated with PVCs and non-sustained VT in non-ischemic LV dysfunction is weak. A systematic review of risk factors in non-ischemic cardiomyopathy failed to identify PVCs and non-sustained VT as independent predictors of prognosis.51 Yet ambulatory ECG monitoring is attractive as a risk stratification tool due to its ubiquitous availability and ease of interpretation. Numerous trials have evaluated interventions, including drug and ICD therapy, to reduce mortality in patients with frequent PVCs or non-sustained VT after MI or in the presence of LV dysfunction. The majority have shown a reduction in SCD-VT/VF but no impact on overall mortality.33, 72, 73 Consequently, the role of ambulatory monitoring in risk stratification is unclear.

Traditional ambulatory monitoring has numerous potential limitations that may confound its use in risk prediction. The most important of these is sampling error. Stratifying patients on the basis of a relatively short term ECG recording (usually <7 days) may falsely classify patients and dilute prognostic ability. Advances in ambulatory monitoring now allow for much longer term recordings, with up to 3 years for implantable cardiac monitors (ICMs).74 Contemporary ICMs allow for automated detection of tachy- and bradyarrhythmias with remote transmission capabilities. The large prospective CARISMA trial evaluated the use of ICMs in patients early post-MI with LVEF <40%.3 It provided novel arrhythmia documentation in a contemporary post-MI population, demonstrating a low rate of SCD-VT/VF (6% over 2 years) and an unexpected high incidence of bradyarrhythmias. The utility of ICMs and other emerging monitoring technologies in risk stratification of SCD-VT/VF has yet to be determined but may represent a considerable advance over limited ambulatory ECG recordings.

3.5. Summary

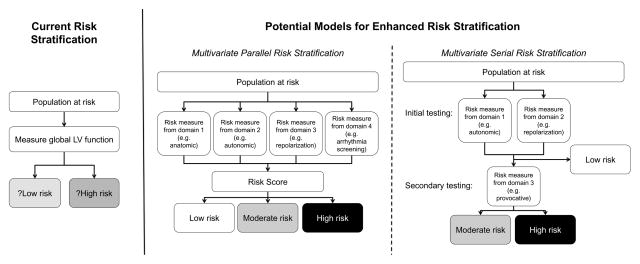

A number of existing and emerging risk stratification tools have demonstrated good prediction for SCD-VT/VF and some of the major studies are summarized in Table 2. However, ongoing research is required to determine their clinical utility, impact on outcomes and cost-effectiveness. It is unlikely that any single measure will have sufficient discrimination to be used in isolation. Rather, combining known measures in a composite score or serial testing needs to be evaluated in this population (figure 1). Serial, or stepwise, testing has already shown promise in enhancing risk stratification, particularly after MI.68, 70, 75 Finally, the impact of contemporary revascularization may decrease the proportion of patients with ischemic heart disease, with a relative increase in patients with LV dysfunction from non-ischemic processes. The majority of risk stratification tools were developed or validated in ischemic populations. Therefore, validation of these methods in the non-ischemic population or the development of a separate risk stratification scheme may be required.60

Table 2.

Selected important studies of risk stratification for SCD-VT/VF in patients with left ventricular dysfunction or myocardial infarction

| Stratification tool | First author, year | Population | N | Outcome | Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification of anatomic substrate abnormalities | |||||

| LV function/LVEF | Bailey et al., 200175 (All modalities) | Post acute MI (meta-analysis) | 7294 | VT/VF or SCD | LVEF <30–40% is an independent predictor (pooled RR 4.3); better risk stratification in combination with other parameters such as HRV |

| Scar assessment | Haugaa et al., 201336 (Echo strain imaging) | >40 days after acute MI | 569 | VT/VF or SCD | Echo strain imaging (mechanical dispersion) independently predictive in patients post MI (HR 1.7 [1.2, 2.5] per 10ms increase) |

| Van Der Burg et al., 200338 (SPECT) | Survivors of SCD with ICM | 153 | VT/VF or death | SPECT excessive scar burden (more than one vascular territory, HR 2.4 [1.0, 5.9) and LVEF ≤30% (HR 2.0 [1.1, 3.5]) only independent predictors | |

| Roes et al, 200942 (MRI) | ICM receiving ICD | 91 | Appropriate ICD therapy | MRI transition zone (heterogeneous scar) only independent predictor (HR 1.5 [1.0, 2.2]) | |

| Kwon et al. 200976 (MRI) | ICM with LVEF <45% | 349 | Death or cardiac transplant | MRI Scar assessment independently predictive (HR 1.02 [1.01, 1.03} per 1% scar); LVEF not predictive | |

| Depolarization | Das et al., 201050 (ECG) | ICM and DCM receiving ICD | 361 | Appropriate ICD therapy | Fragmented QRS by ECG predictor of ICD therapy (HR 7.6 [3.3, 7.4]) but not overall mortality (HR 1.2 [0.5, 3.0]) |

| Autonomic testing | |||||

| Heart rate variability/baroreceptor sensitivity | La Rovere et al., 199856 | Recent (<28 days) MI | 1284 | Cardiac death | Both low HRV (SDNN <70ms, HR 3.2 [1.4, 7.4]) and BRS (<3.0, HR 2.8 [1.2, 6.2]) were independent predictors; additive prediction when combined with LVEF <35% |

| Heart rate turbulence | Ghuran et al., 200277 | Recent (<28 days) MI | 1212 | VT/VF or SCD | HRT was an independent predictor (turbulence onset HR 4.1 [1.7, 9.8]; turbulence slope HR 3.5 [1.8, 7.1]), in addition to LVEF |

| Exner et al., 200719 | Recent (<7days) MI and LVEF <50% | 322 | VT/VF arrest or cardiac death | HRT (abnormal onset or slope) an independent predictor when measured 10–14 weeks post MI (HR 2.9 [1.1, 7.5]); best prediction with a combination of HRT and TWA | |

| Identification of repolarization abnormalities | |||||

| QT dispersion/variability | Haigney et al., 200463 | ICM and LVEF≤30% | 1232 | ICD therapy | The highest quartile of QT variability was an independent predictor (HR 2.2 [1.4, 3.6]), but poor NPV |

| T-wave alternans | Exner et al., 200719 | Recent (<7days) MI and LVEF <50% | 322 | VT/VF arrest or cardiac death | Non-negative TWA was an independent predictor when measured 10–14 weeks post MI (HR 2.8 [1.1, 7.0]); best prediction with a combination of HRT and TWA |

| Gold et al., 200866 | ICM and DCM LVEF <35% | 490 | SCD, VT or ICD therapy | Non-negative TWA was not an independent predictor (HR 1.28 [0.7, 2.5]) | |

| Chan et al., 200878 | ICM and LVEF ≤35% | 768 | Deaht and ICD therapy | Non-negative TWA was an independent predictor (at 1 year HR 2.2 [1.1, 4.3]) | |

| Provocative testing/screening for non-sustained arrhythmias | |||||

| EP testing | Buxton et al. 200079 (MUSTT substudy) | ICM, LVEF <40% and non-sustained VT | 1750 | VT/VF or SCD | A negative EP study was protective (HR 0.66 [0.5, 0.8]) in comparison to those with positive EP study on no therapy. Event rate with negative EP study still 12% at 2 years. |

| Costantini et al. 200968 | ICM, LVEF <40% and non-sustained VT | 566 | ICD shock or SCD | A positive EP study was a predictor (HR 2.4, no confidence interval reported). EP study was more predictive in combination with TWA. | |

The included studies are meant to highlight important literature but do not represent a comprehensive list of studies evaluating tools for risk stratification.

Abbreviations: LV, left ventricle, LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; VT, ventricular tachycardia; VF, ventricular fibrillation; SCD, sudden cardiac death; RR, relative risk; HRV, heart rate variability; HR, hazard ratio; SPECT, single photon emission computed tomography; ICM, ischemic cardiomyopathy; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; ECG, electrocardiogram; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; SDNN, standard deviation of normal to normal RR intervals; BRS, baroreceptor sensitivity; TWA, t-wave alternans; EP, electrophysiology.

Figure 1.

Models for enhanced risk stratification

Abbreviations: LV, left ventricular.

4. Risk stratification in the general population

The majority of research and advances in risk stratification have focused on those at highest risk, namely those with MI and/or LV dysfunction. This, however, ignores the fundamental epidemiology of SCD-VT/VF: the majority of SCD-VT/VF occurs in patients with no known heart disease.80–82 Decreasing the population impact of SCD-VT/VF will require improved risk stratification in the general population.

The standard ECG is a potentially attractive tool for large scale screening of the general population due to its relative low cost and ubiquitous availability. The most comprehensive data on ECG measures and risk of both cardiac death and arrhythmic death come from a series of studies using a Finnish cohort of over 10,000 middle-aged subjects followed for a mean of 30 years.83–86 Classification of death was performed retrospectively from available records, which comes with inherent limitations. Nevertheless, in this cohort, QRS prolongation of ≥110ms (prevalence 1.3%, relative risk 2.14 [1.38, 3.33]), intraventricular conduction delay (but not bundle branch block; prevalence 0.6%, relative risk 3.11 [1.74, 5.54]) and early repolarization of at least 0.2mV (prevalence 0.3%, relative risk 2.92 [1.45, 5.89]) were all independent predictors of arrhythmic death. 83–86 The low prevalence of each of these markers may limit their utility in large scale screening.

Autopsy and epidemiologic data implicate ruptured atherosclerotic plaques (acute coronary syndromes) as a major cause of SCD-VT/VF in the general population.15 Risk stratification for CAD is well established in clinical practice, yet existing tools were developed to predict overall cardiovascular mortality or the presence of fixed, severe CAD. Most atherosclerotic plaque ruptures occur in non-severe lesions and no current risk assessment tools accurately identify patients at risk of ruptured plaque. The ability to identify individuals at risk of plaque rupture would undoubtedly have an impact on prevention of SCD-VT/VF in the general population. Two potential avenues that show promise for better risk prediction in the general population are serum biomarkers and imaging of atherosclerotic plaques.

Serum biomarkers are attractive because of their relatively low cost and generally wide availability. Biomarkers under investigation for risk stratification can broadly be divided into: inflammatory markers, free-fatty acids and hemodynamic markers.87 Inflammation plays a central role in the pathogenesis of plaque rupture. C-reactive protein (CRP) is the most widely studied marker of inflammation, though its use in predicting SCD is uncertain. To date, prospective cohort studies have shown mixed results as to whether CRP levels are independent predictors of SCD.88, 89 Interleukin-6 is another marker of inflammation. In the large PRIME observational study, the highest tertile of interleukin levels were strongly and independently predictive of SCD (estimated odds ratio >3.0).90

Fatty acids are another potential useful biomarker for SCD-VT/VF. The pathophysiologic effects of fatty acids are not completely understood but subtypes that are protective and confer increased risk have been identified. Non-esterified free fatty acids (NEFA) have been associated with higher risk of SCD. In the Paris Prospective Study I of middle-aged men without known heart disease, NEFA levels were a moderate independent predictor of SCD.91 The most widely studied hemodynamic marker has been B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP). BNP levels have been shown to predict SCD and ICD therapy in high risk populations.87 Two large studies in populations without heart disease have identified N-terminal BNP as an independent predictor of SCD (relative risk 1.5–2.5).89, 92 However, hemodynamic markers are also a significant predictor of non-sudden cardiac mortality and their specificity for SCD-VT/VF remains to be elucidated. Biomarkers may be useful in refining risk of SCD-VT/VF in the general population, particularly in those at intermediate or high risk of CAD. Large-scale comprehensive biomarker studies are needed to validate what are typically promising but inconclusive novel reported markers.

Advances in non-invasive cardiac imaging, particularly coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA), now allow for characterization of atherosclerotic plaque features beyond simple degree of stenosis. In autopsy studies, several features of atherosclerotic plaques have been associated with plaque rupture. Correlates of these features can be accurately identified on CCTA. Two preliminary studies have correlated such adverse plaque features with subsequent risk of acute MI.93, 94 Further ongoing studies aim to confirm the ability of CCTA to predict acute coronary syndromes in larger populations at risk. Resource implications would obviously limit the widespread use of CCTA for risk stratification in the general population. However, CCTA may be effective in targeted subgroups or as part of a serial testing strategy. Improving risk stratification of SCD-VT/VF in the general population remains the most pressing and challenging obstacle for the treatment of SCD. Given the etiologic link between atherosclerotic plaque rupture and SCD-VT/VF in this population, strategies to better identify those at risk of acute coronary syndromes are likely to be the highest yield. Both serum biomarkers and CCTA show considerable promise in this regard.

5. Risk stratification in other populations

Unique approaches to risk stratification have been developed for specific cardiac phenotypes, notably hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and inherited arrhythmia syndromes.95, 96 A discussion of risk stratification in these disorders is beyond the scope of this article. Other populations, defined not by a specific cardiac phenotype but rather by demographic or comorbid factors, also warrant discussion to highlight challenges in risk stratification. Two such populations are those with diabetes mellitus and chronic renal failure.

Diabetes mellitus is present in approximately one fifth of all cases of SCD.97 The presence of diabetes appears to confer an independent increase in risk of SCD, particularly in patients without previous MI.98 Diabetes itself is a risk factor for atherosclerosis and MI, but diabetes may confer an increased risk of SCD by mechanisms beyond propensity to CAD.

Cardiac autonomic neuropathy appears to be a common finding in patients with diabetes.98, 99 Autonomic dysfunction has been associated with an increased risk of overall mortality in diabetes, but an independent association with SCD has not been established to date.100 This mirrors observations regarding HRV in non-diabetic populations. Diabetes may increase vulnerability to VT/VF by influencing dynamic myocardial electrical substrate. QT interval prolongation is present in a higher proportion of subjects with diabetes than in controls and is independently associated with overall mortality.101 Hypoglycemia may be one factor influencing repolarization, including QT prolongation, in diabetes.98 Other measures of repolarization abnormalities, such as TWA have not been studied in a solely diabetic population to date. Nonetheless, measures of autonomic function and dynamic electrical substrate may have particular importance for SCD-VT/VF in the diabetic population.

SCD is also frequent in the chronic renal failure population and particularly prevalent in patients on dialysis.102, 103 However, defining and classifying SCD in dialysis patients is problematic as the onset of symptoms may be difficult to establish and multiple contributing factors may be present. High overall mortality rates in dialysis patients means risk stratification for SCD-VT/VF must account for competing risks. This is highlighted by the lack of benefit from ICD therapy in dialysis patients who meet traditional LV function criteria for primary prevention ICD implantation.104 The use of ICMs in dialysis patients may provide insight into the mechanism of SCD, allowing more accurate estimation of the burden of SCD-VT/VF versus non-VT/VF SCD. However, no such data are available at present.

The pathophysiology of SCD in dialysis patients undoubtedly has unique features that are not present in other populations. Dialysis results in large swings in electrolyte balance that may influence dynamic electrical substrate. This is supported by the increased risk of SCD with increased intervals between dialysis runs.105 Abnormal parathyroid hormone and bone metabolism in chronic kidney disease may also contribute to the risk of SCD.106 It is clear that risk stratification in advanced renal failure poses unique challenges. To improve risk stratification for SCD-VT/VF in this population, further research is required to enhance our understanding of the mechanisms of SCD and its pathophysiology in advanced renal disease.

6. Future directions

Risk stratification for SCD-VT/VF remains primitive in clinical practice, yet this need not be so going forward. A number of novel risk stratification techniques have been identified that show considerable promise. The majority of these have demonstrated predictive ability but the clinical utility, impact on outcomes and cost-effectiveness of these techniques must be evaluated.107 There are important challenges in risk stratification that must be addressed before meaningful progress can be made.

Contemporary practice is almost solely reliant on LVEF for risk stratification, to the exclusion of other known predictors of risk. More sophisticated models are required to provide accurate estimates of risk to allow physicians and patients to make informed treatment decisions. It is extremely unlikely that any single existing or novel risk marker will have adequate discriminant ability. Multivariable risk modeling has been incorporated into clinical practice for atherosclerosis, bypass surgery and acute coronary syndromes.15, 16, 108 Relatively simple risk prediction tools have been developed to predict those with reduced LVEF who would not benefit from ICD therapy.12, 109 Further evaluations of serial testing, particularly strategies of initial testing using a technique with a strong negative predictive value followed by selective testing with a technique with higher positive predictive values, are needed. The ubiquity of electronic medical records and ready access to hand-held computing have eliminated virtually all barriers to rapid, yet accurate risk stratification based on multidimensional input.

There are significant financial, logistic and regulatory barriers to evaluation of risk stratification techniques for SCD-VT/VF.110 For many of the important research questions in risk stratification, a conventional randomized control design with treatment and control group will be impractical or impossible. This is particularly true for populations with low event rates for SCD-VT/VF. Randomized controlled trial data also need not be the only standard for assessing the efficacy of risk stratification strategies. Alternate methodologies, such as cluster randomized trials, randomized registries and prospective cohort studies are more suited to populations with low event rates and complex risk modeling.111

There are exciting advances in medical and device therapy for SCD-VT/VF.112, 113 Yet defining the roles of these and existing treatments can only take place in the setting of accurate risk stratification. Improved risk stratification is central to tackling this important public health concern.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

7. Sources of Funding

Dr. Deyell is supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Medical Research and Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Dr. Krahn receives support from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, the Sauder Family and Heart and Stroke Foundation Chair in Cardiology and the Paul Brunes Chair in Heart Rhythm Disorders.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- BNP

brain natriuretic peptide

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CCTA

coronary computed tomography angiography

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- HRV

heart rate variability

- HRT

heart rate turbulence

- ICD

implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

- ICM

implantable cardiac monitor

- LV

left ventricle/ventricular

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- NEFA

nonesterified free fatty acids

- PEA

pulseless electrical activity

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PVC

premature ventricular complex

- SAECG

Signal-averaged electrocardiogram

- SCD

sudden cardiac death

- SCD-VT/VF

sudden cardiac death due to ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation

- SPECT

single photon emission computed tomography

- TWA

T-wave alternans

- VF

ventricular fibrillation

- VT

ventricular tachycardia

Footnotes

8. Disclosures

Drs. Deyell and Krahn have no disclosures relevant to the content of this article. Dr. Goldberger is the Director of the Path to Improved Risk Stratification, NFP, a not-for-profit think tank that has received unrestricted educational grants from Boston Scientific, Medtronic, and St. Jude. He has also received consulting fees from Medtronic and GE Medical.

References

- 1.Lubinski A, Bissinger A, Boersma L, Leenhardt A, Merkely B, Oto A, Proclemer A, Brugada J, Vardas PE, Wolpert C. Determinants of geographic variations in implantation of cardiac defibrillators in the European Society of Cardiology member countries--data from the European Heart Rhythm Association White Book. Europace. 2011;13:654–62. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hulleman M, Berdowski J, de Groot JR, van Dessel PF, Borleffs CJ, Blom MT, Bardai A, de Cock CC, Tan HL, Tijssen JG, Koster RW. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators have reduced the incidence of resuscitation for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest caused by lethal arrhythmias. Circulation. 2012;126:815–21. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.089425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloch Thomsen PE, Jons C, Raatikainen MJP, Moerch Joergensen R, Hartikainen J, Virtanen V, Boland J, Anttonen O, Gang UJ, Hoest N, Boersma LVA, Platou ES, Becker D, Messier MD, Huikuri HV Arrhythmias ftC and Group RSAAMIS. Long-Term Recording of Cardiac Arrhythmias With an Implantable Cardiac Monitor in Patients With Reduced Ejection Fraction After Acute Myocardial Infarction: The Cardiac Arrhythmias and Risk Stratification After Acute Myocardial Infarction (CARISMA) Study. Circulation. 2010;122:1258–1264. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.902148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Youngquist ST, Kaji AH, Niemann JT. Beta-blocker use and the changing epidemiology of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest rhythms. Resuscitation. 2008;76:376–80. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levantesi G, Scarano M, Marfisi R, Borrelli G, Rutjes AWS, Silletta MG, Tognoni G, Marchioli R. Meta-Analysis of Effect of Statin Treatment on Risk of Sudden Death. The American journal of cardiology. 2007;100:1644–1650. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engdahl J, Bang A, Lindqvist J, Herlitz J. Factors affecting short- and long-term prognosis among 1069 patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest and pulseless electrical activity. Resuscitation. 2001;51:17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9572(01)00377-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myerburg RJ, Halperin H, Egan DA, Boineau R, Chugh SS, Gillis AM, Goldhaber JI, Lathrop DA, Liu P, Niemann JT, Ornato JP, Sopko G, Van Eyk JE, Walcott GP, Weisfeldt ML, Wright JD, Zipes DP. Pulseless electric activity: definition, causes, mechanisms, management, and research priorities for the next decade: report from a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute workshop. Circulation. 2013;128:2532–41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberger JJ, Buxton AE, Cain M, Costantini O, Exner DV, Knight BP, Lloyd-Jones D, Kadish AH, Lee B, Moss A, Myerburg R, Olgin J, Passman R, Rosenbaum D, Stevenson W, Zareba W, Zipes DP. Risk stratification for arrhythmic sudden cardiac death: identifying the roadblocks. Circulation. 2011;123:2423–30. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.959734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, Estes NA, 3rd, Freedman RA, Gettes LS, Gillinov AM, Gregoratos G, Hammill SC, Hayes DL, Hlatky MA, Newby LK, Page RL, Schoenfeld MH, Silka MJ, Stevenson LW, Sweeney MO, Tracy CM, Epstein AE, Darbar D, DiMarco JP, Dunbar SB, Estes NA, 3rd, Ferguson TB, Jr, Hammill SC, Karasik PE, Link MS, Marine JE, Schoenfeld MH, Shanker AJ, Silka MJ, Stevenson LW, Stevenson WG, Varosy PD American College of Cardiology F, American Heart Association Task Force on Practice G, Heart Rhythm S. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:e6–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang AS, Ross H, Simpson CS, Mitchell LB, Dorian P, Goeree R, Hoffmaster B, Arnold M, Talajic M Canadian Heart Rhythm S, Canadian Cardiovascular S. Canadian Cardiovascular Society/Canadian Heart Rhythm Society position paper on implantable cardioverter defibrillator use in Canada. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2005;21(Suppl A):11A–18A. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buxton AE, Lee KL, Hafley GE, Pires LA, Fisher JD, Gold MR, Josephson ME, Lehmann MH, Prystowsky EN, Investigators M. Limitations of ejection fraction for prediction of sudden death risk in patients with coronary artery disease: lessons from the MUSTT study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1150–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldenberg I, Vyas AK, Hall WJ, Moss AJ, Wang H, He H, Zareba W, McNitt S, Andrews ML, Investigators M-I. Risk stratification for primary implantation of a cardioverter-defibrillator in patients with ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:288–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arntz HR, Willich SN, Schreiber C, Bruggemann T, Stern R, Schultheiss HP. Diurnal, weekly and seasonal variation of sudden death. Population-based analysis of 24,061 consecutive cases. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:315–20. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1999.1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerber Y, Jacobsen SJ, Killian JM, Weston SA, Roger VL. Seasonality and daily weather conditions in relation to myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1979 to 2002. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:287–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goff DC, Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, Coady S, D’Agostino RB, Gibbons R, Greenland P, Lackland DT, Levy D, O’Donnell CJ, Robinson JG, Schwartz JS, Shero ST, Smith SC, Jr, Sorlie P, Stone NJ, Wilson PW, Jordan HS, Nevo L, Wnek J, Anderson JL, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Bozkurt B, Brindis RG, Curtis LH, DeMets D, Hochman JS, Kovacs RJ, Ohman EM, Pressler SJ, Sellke FW, Shen WK, Smith SC, Jr, Tomaselli GF. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the assessment of cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:S49–73. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437741.48606.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nashef SA, Roques F, Sharples LD, Nilsson J, Smith C, Goldstone AR, Lockowandt U. EuroSCORE II. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery: official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2012;41:734–44. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezs043. discussion 744–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy WC, Lee KL, Hellkamp AS, Poole JE, Mozaffarian D, Linker DT, Maggioni AP, Anand I, Poole-Wilson PA, Fishbein DP, Johnson G, Anderson J, Mark DB, Bardy GH. Maximizing survival benefit with primary prevention implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in a heart failure population. Circulation. 2009;120:835–42. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.816884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaudron P, Kugler I, Hu K, Bauer W, Eilles C, Ertl G. Time course of cardiac structural, functional and electrical changes in asymptomatic patients after myocardial infarction: their inter-relation and prognostic impact. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:33–40. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01319-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Exner DV, Kavanagh KM, Slawnych MP, Mitchell LB, Ramadan D, Aggarwal SG, Noullett C, Van Schaik A, Mitchell RT, Shibata MA, Gulamhussein S, McMeekin J, Tymchak W, Schnell G, Gillis AM, Sheldon RS, Fick GH, Duff HJ, Investigators R. Noninvasive risk assessment early after a myocardial infarction the REFINE study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2275–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huikuri HV, Raatikainen MJ, Moerch-Joergensen R, Hartikainen J, Virtanen V, Boland J, Anttonen O, Hoest N, Boersma LV, Platou ES, Messier MD, Bloch-Thomsen PE, Cardiac A. Risk Stratification after Acute Myocardial Infarction study g. Prediction of fatal or near-fatal cardiac arrhythmia events in patients with depressed left ventricular function after an acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:689–98. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Myerburg RJ, Reddy V, Castellanos A. Indications for implantable cardioverter-defibrillators based on evidence and judgment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:747–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rea TD, Pearce RM, Raghunathan TE, Lemaitre RN, Sotoodehnia N, Jouven X, Siscovick DS. Incidence of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. The American journal of cardiology. 2004;93:1455–60. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zareba W, Moss AJ. Noninvasive risk stratification in postinfarction patients with severe left ventricular dysfunction and methodology of the MADIT II noninvasive electrocardiology substudy. Journal of electrocardiology. 2003;36(Suppl):101–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2003.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsia HH, Marchlinski FE. Characterization of the electroanatomic substrate for monomorphic ventricular tachycardia in patients with nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Pacing and clinical electrophysiology: PACE. 2002;25:1114–27. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9592.2002.01114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stevenson WG, Brugada P, Waldecker B, Zehender M, Wellens HJ. Clinical, angiographic, and electrophysiologic findings in patients with aborted sudden death as compared with patients with sustained ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1985;71:1146–52. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.71.6.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vassallo JA, Cassidy D, Simson MB, Buxton AE, Marchlinski FE, Josephson ME. Relation of late potentials to site of origin of ventricular tachycardia associated with coronary heart disease. The American journal of cardiology. 1985;55:985–989. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90731-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bigger JT, Jr, Fleiss JL, Kleiger R, Miller JP, Rolnitzky LM. The relationships among ventricular arrhythmias, left ventricular dysfunction, and mortality in the 2 years after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1984;69:250–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.69.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gradman A, Deedwania P, Cody R, Massie B, Packer M, Pitt B, Goldstein S. Predictors of total mortality and sudden death in mild to moderate heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;14:564–570. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90093-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, Poole JE, Packer DL, Boineau R, Domanski M, Troutman C, Anderson J, Johnson G, McNulty SE, Clapp-Channing N, Davidson-Ray LD, Fraulo ES, Fishbein DP, Luceri RM, Ip JH. Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial I. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. The New England journal of medicine. 2005;352:225–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kadish A, Dyer A, Daubert JP, Quigg R, Estes NA, Anderson KP, Calkins H, Hoch D, Goldberger J, Shalaby A, Sanders WE, Schaechter A, Levine JH. Defibrillators in Non-Ischemic Cardiomyopathy Treatment Evaluation I. Prophylactic defibrillator implantation in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. The New England journal of medicine. 2004;350:2151–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Klein H, Wilber DJ, Cannom DS, Daubert JP, Higgins SL, Brown MW, Andrews ML Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial III. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. The New England journal of medicine. 2002;346:877–83. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bigger JT., Jr Prophylactic use of implanted cardiac defibrillators in patients at high risk for ventricular arrhythmias after coronary-artery bypass graft surgery. Coronary Artery Bypass Graft (CABG) Patch Trial Investigators. The New England journal of medicine. 1997;337:1569–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711273372201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hohnloser SH, Kuck KH, Dorian P, Roberts RS, Hampton JR, Hatala R, Fain E, Gent M, Connolly SJ, Investigators D. Prophylactic use of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator after acute myocardial infarction. The New England journal of medicine. 2004;351:2481–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bello D, Fieno DS, Kim RJ, Pereles FS, Passman R, Song G, Kadish AH, Goldberger JJ. Infarct morphology identifies patients with substrate for sustained ventricular tachycardia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1104–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dandel M, Hetzer R. Echocardiographic strain and strain rate imaging — Clinical applications. Int J Cardiol. 2009;132:11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.06.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haugaa KH, Grenne BL, Eek CH, Ersboll M, Valeur N, Svendsen JH, Florian A, Sjoli B, Brunvand H, Kober L, Voigt JU, Desmet W, Smiseth OA, Edvardsen T. Strain echocardiography improves risk prediction of ventricular arrhythmias after myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovascular imaging. 2013;6:841–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dorbala S, Hachamovitch R, Curillova Z, Thomas D, Vangala D, Kwong RY, Di Carli MF. Incremental prognostic value of gated Rb-82 positron emission tomography myocardial perfusion imaging over clinical variables and rest LVEF. JACC Cardiovascular imaging. 2009;2:846–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Burg AE, Bax JJ, Boersma E, Pauwels EK, van der Wall EE, Schalij MJ. Impact of viability, ischemia, scar tissue, and revascularization on outcome after aborted sudden death. Circulation. 2003;108:1954–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091410.19963.9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bertini M, Schalij MJ, Bax JJ, Delgado V. Emerging role of multimodality imaging to evaluate patients at risk for sudden cardiac death. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:525–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.110.961532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stevenson WG, Friedman PL, Sager PT, Saxon LA, Kocovic D, Harada T, Wiener I, Khan H. Exploring postinfarction reentrant ventricular tachycardia with entrainment mapping. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:1180–9. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Perez-David E, Arenal A, Rubio-Guivernau JL, del Castillo R, Atea L, Arbelo E, Caballero E, Celorrio V, Datino T, Gonzalez-Torrecilla E, Atienza F, Ledesma-Carbayo MJ, Bermejo J, Medina A, Fernandez-Aviles F. Noninvasive identification of ventricular tachycardia-related conducting channels using contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging in patients with chronic myocardial infarction: comparison of signal intensity scar mapping and endocardial voltage mapping. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:184–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roes SD, Borleffs CJ, van der Geest RJ, Westenberg JJ, Marsan NA, Kaandorp TA, Reiber JH, Zeppenfeld K, Lamb HJ, de Roos A, Schalij MJ, Bax JJ. Infarct tissue heterogeneity assessed with contrast-enhanced MRI predicts spontaneous ventricular arrhythmia in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:183–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.826529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidt A, Azevedo CF, Cheng A, Gupta SN, Bluemke DA, Foo TK, Gerstenblith G, Weiss RG, Marban E, Tomaselli GF, Lima JA, Wu KC. Infarct tissue heterogeneity by magnetic resonance imaging identifies enhanced cardiac arrhythmia susceptibility in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Circulation. 2007;115:2006–14. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.653568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wu KC, Gerstenblith G, Guallar E, Marine JE, Dalal D, Cheng A, Marban E, Lima JA, Tomaselli GF, Weiss RG. Combined cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and C-reactive protein levels identify a cohort at low risk for defibrillator firings and death. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5:178–86. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.111.968024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kadish AH, Bello D, Finn JP, Bonow RO, Schaechter A, Subacius H, Albert C, Daubert JP, Fonseca CG, Goldberger JJ. Rationale and design for the Defibrillators to Reduce Risk by Magnetic Resonance Imaging Evaluation (DETERMINE) trial. Journal of cardiovascular electrophysiology. 2009;20:982–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Buxton AE, Sweeney MO, Wathen MS, Josephson ME, Otterness MF, Hogan-Miller E, Stark AJ, Degroot PJ Pain FRIII. QRS duration does not predict occurrence of ventricular tachyarrhythmias in patients with implanted cardioverter-defibrillators. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:310–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh JP, Hall WJ, McNitt S, Wang H, Daubert JP, Zareba W, Ruskin JN, Moss AJ, Investigators M-I. Factors influencing appropriate firing of the implanted defibrillator for ventricular tachycardia/fibrillation: findings from the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II (MADIT-II) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1712–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Simson MB, Untereker WJ, Spielman SR, Horowitz LN, Marcus NH, Falcone RA, Harken AH, Josephson ME. Relation between late potentials on the body surface and directly recorded fragmented electrograms in patients with ventricular tachycardia. The American journal of cardiology. 1983;51:105–12. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(83)80020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldberger JJ, Cain ME, Hohnloser SH, Kadish AH, Knight BP, Lauer MS, Maron BJ, Page RL, Passman RS, Siscovick D, Stevenson WG, Zipes DP American Heart A, American College of Cardiology F, Heart Rhythm S, American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation/Heart Rhythm Society Scientific Statement on Noninvasive Risk Stratification Techniques for Identifying Patients at Risk for Sudden Cardiac Death. A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology Committee on Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1179–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Das MK, Maskoun W, Shen C, Michael MA, Suradi H, Desai M, Subbarao R, Bhakta D. Fragmented QRS on twelve-lead electrocardiogram predicts arrhythmic events in patients with ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.09.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldberger JJ, Subačius H, Patel T, Cunnane R, Kadish AH. Sudden Cardiac Death Risk Stratification in Patients With Nonischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1879–1889. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lown B, Verrier RL. Neural activity and ventricular fibrillation. The New England journal of medicine. 1976;294:1165–70. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197605202942107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wolf MM, Varigos GA, Hunt D, Sloman JG. Sinus arrhythmia in acute myocardial infarction. The Medical journal of Australia. 1978;2:52–3. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1978.tb131339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation and clinical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Circulation. 1996;93:1043–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.La Rovere MT, Pinna GD, Maestri R, Mortara A, Capomolla S, Febo O, Ferrari R, Franchini M, Gnemmi M, Opasich C, Riccardi PG, Traversi E, Cobelli F. Short-term heart rate variability strongly predicts sudden cardiac death in chronic heart failure patients. Circulation. 2003;107:565–70. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000047275.25795.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.La Rovere MT, Bigger JT, Jr, Marcus FI, Mortara A, Schwartz PJ. Baroreflex sensitivity and heart-rate variability in prediction of total cardiac mortality after myocardial infarction. ATRAMI (Autonomic Tone and Reflexes After Myocardial Infarction) Investigators. Lancet. 1998;351:478–84. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)11144-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Watanabe MA, Marine JE, Sheldon R, Josephson ME. Effects of ventricular premature stimulus coupling interval on blood pressure and heart rate turbulence. Circulation. 2002;106:325–30. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000022163.24831.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roach D, Koshman ML, Duff H, Sheldon R. Induction of heart rate and blood pressure turbulence in the electrophysiologic laboratory. The American journal of cardiology. 2002;90:1098–102. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02775-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schmidt G, Malik M, Barthel P, Schneider R, Ulm K, Rolnitzky L, Camm AJ, Bigger JT, Jr, Schomig A. Heart-rate turbulence after ventricular premature beats as a predictor of mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1999;353:1390–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)08428-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goldberger JJ, Subacius H, Patel T, Cunnane R, Kadish AH. Sudden cardiac death risk stratification in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1879–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fallavollita JA, Heavey BM, Luisi AJ, Jr, Michalek SM, Baldwa S, Mashtare TL, Jr, Hutson AD, Dekemp RA, Haka MS, Sajjad M, Cimato TR, Curtis AB, Cain ME, Canty JM., Jr Regional myocardial sympathetic denervation predicts the risk of sudden cardiac arrest in ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:141–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jacobson AF, Senior R, Cerqueira MD, Wong ND, Thomas GS, Lopez VA, Agostini D, Weiland F, Chandna H, Narula J, Investigators A-H. Myocardial iodine-123 meta-iodobenzylguanidine imaging and cardiac events in heart failure. Results of the prospective ADMIRE-HF (AdreView Myocardial Imaging for Risk Evaluation in Heart Failure) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2212–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Haigney MC, Zareba W, Gentlesk PJ, Goldstein RE, Illovsky M, McNitt S, Andrews ML, Moss AJ Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial IIi. QT interval variability and spontaneous ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation in the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial (MADIT) II patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1481–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pastore JM, Girouard SD, Laurita KR, Akar FG, Rosenbaum DS. Mechanism linking T-wave alternans to the genesis of cardiac fibrillation. Circulation. 1999;99:1385–94. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.10.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nearing BD, Verrier RL. Modified moving average analysis of T-wave alternans to predict ventricular fibrillation with high accuracy. Journal of applied physiology. 2002;92:541–9. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00592.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gold MR, Ip JH, Costantini O, Poole JE, McNulty S, Mark DB, Lee KL, Bardy GH. Role of Microvolt T-Wave Alternans in Assessment of Arrhythmia Vulnerability Among Patients With Heart Failure and Systolic Dysfunction: Primary Results From the T-Wave Alternans Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial Substudy. Circulation. 2008;118:2022–2028. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.748962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nieminen T, Scirica BM, Pegler JRM, Tavares C, Pagotto VPF, Kanas AF, Sobrado MF, Nearing BD, Umez-Eronini AA, Morrow DA, Belardinelli L, Verrier RL. Relation of T-Wave Alternans to Mortality and Nonsustained Ventricular Tachycardia in Patients With Non–ST-Segment Elevation Acute Coronary Syndrome from the MERLIN-TIMI 36 Trial of Ranolazine Versus Placebo. The American journal of cardiology. 2014;114:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Costantini O, Hohnloser SH, Kirk MM, Lerman BB, Baker JH, 2nd, Sethuraman B, Dettmer MM, Rosenbaum DS, Investigators AT. The ABCD (Alternans Before Cardioverter Defibrillator) Trial: strategies using T-wave alternans to improve efficiency of sudden cardiac death prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:471–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Verrier RL, Klingenheben T, Malik M, El-Sherif N, Exner DV, Hohnloser SH, Ikeda T, Martinez JP, Narayan SM, Nieminen T, Rosenbaum DS. Microvolt T-wave alternans physiological basis, methods of measurement, and clinical utility--consensus guideline by International Society for Holter and Noninvasive Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1309–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Buxton AE, Lee KL, Fisher JD, Josephson ME, Prystowsky EN, Hafley G. A Randomized Study of the Prevention of Sudden Death in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;341:1882–1890. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912163412503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kotler MN, Tabatznik B, Mower MM, Tominaga S. Prognostic significance of ventricular ectopic beats with respect to sudden death in the late postinfarction period. Circulation. 1973;47:959–66. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.47.5.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cairns JA, Connolly SJ, Roberts R, Gent M. Randomised trial of outcome after myocardial infarction in patients with frequent or repetitive ventricular premature depolarisations: CAMIAT. Canadian Amiodarone Myocardial Infarction Arrhythmia Trial Investigators. Lancet. 1997;349:675–82. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)08171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Singh SN, Fletcher RD, Fisher SG, Singh BN, Lewis HD, Deedwania PC, Massie BM, Colling C, Lazzeri D. Amiodarone in patients with congestive heart failure and asymptomatic ventricular arrhythmia. Survival Trial of Antiarrhythmic Therapy in Congestive Heart Failure. The New England journal of medicine. 1995;333:77–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507133330201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Krahn AD, Klein GJ, Skanes AC, Yee R. Insertable Loop Recorder Use for Detection of Intermittent Arrhythmias. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology. 2004;27:657–664. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2004.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bailey JJ, Berson AS, Handelsman H, Hodges M. Utility of current risk stratification tests for predicting major arrhythmic events after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1902–11. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01667-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kwon DH, Halley CM, Carrigan TP, Zysek V, Popovic ZB, Setser R, Schoenhagen P, Starling RC, Flamm SD, Desai MY. Extent of left ventricular scar predicts outcomes in ischemic cardiomyopathy patients with significantly reduced systolic function: a delayed hyperenhancement cardiac magnetic resonance study. JACC Cardiovascular imaging. 2009;2:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ghuran A, Reid F, La Rovere MT, Schmidt G, Bigger JT, Jr, Camm AJ, Schwartz PJ, Malik M, Investigators A. Heart rate turbulence-based predictors of fatal and nonfatal cardiac arrest (The Autonomic Tone and Reflexes After Myocardial Infarction substudy) The American journal of cardiology. 2002;89:184–90. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02198-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chan PS, Kereiakes DJ, Bartone C, Chow T. Usefulness of microvolt T-wave alternans to predict outcomes in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy beyond one year. The American journal of cardiology. 2008;102:280–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Buxton AE, Lee KL, DiCarlo L, Gold MR, Greer GS, Prystowsky EN, O’Toole MF, Tang A, Fisher JD, Coromilas J, Talajic M, Hafley G. Electrophysiologic Testing to Identify Patients with Coronary Artery Disease Who Are at Risk for Sudden Death. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342:1937–1945. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006293422602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Albert CM, Chae CU, Grodstein F, Rose LM, Rexrode KM, Ruskin JN, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE. Prospective study of sudden cardiac death among women in the United States. Circulation. 2003;107:2096–101. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000065223.21530.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chugh SS, Jui J, Gunson K, Stecker EC, John BT, Thompson B, Ilias N, Vickers C, Dogra V, Daya M, Kron J, Zheng ZJ, Mensah G, McAnulty J. Current burden of sudden cardiac death: multiple source surveillance versus retrospective death certificate-based review in a large U.S. community. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:1268–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.de Vreede-Swagemakers JJ, Gorgels AP, Dubois-Arbouw WI, van Ree JW, Daemen MJ, Houben LG, Wellens HJ. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the 1990’s: a population-based study in the Maastricht area on incidence, characteristics and survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1500–5. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00355-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Aro AL, Anttonen O, Tikkanen JT, Junttila MJ, Kerola T, Rissanen HA, Reunanen A, Huikuri HV. Intraventricular conduction delay in a standard 12-lead electrocardiogram as a predictor of mortality in the general population. Circulation Arrhythmia and electrophysiology. 2011;4:704–10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.963561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Aro AL, Anttonen O, Tikkanen JT, Junttila MJ, Kerola T, Rissanen HA, Reunanen A, Huikuri HV. Prevalence and prognostic significance of T-wave inversions in right precordial leads of a 12-lead electrocardiogram in the middle-aged subjects. Circulation. 2012;125:2572–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.098681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Aro AL, Huikuri HV, Tikkanen JT, Junttila MJ, Rissanen HA, Reunanen A, Anttonen O. QRS-T angle as a predictor of sudden cardiac death in a middle-aged general population. Europace. 2012;14:872–6. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tikkanen JT, Anttonen O, Junttila MJ, Aro AL, Kerola T, Rissanen HA, Reunanen A, Huikuri HV. Long-term outcome associated with early repolarization on electrocardiography. The New England journal of medicine. 2009;361:2529–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Havmöller R, Chugh SS. Plasma Biomarkers for Prediction of Sudden Cardiac Death: Another Piece of the Risk Stratification Puzzle? Circ. 2012;5:237–243. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.968057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Albert CM, Ma J, Rifai N, Stampfer MJ, Ridker PM. Prospective study of C-reactive protein, homocysteine, and plasma lipid levels as predictors of sudden cardiac death. Circulation. 2002;105:2595–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000017493.03108.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]