Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has increasingly become a “geriatric” disease, with a dramatic rise in incidence in the aging population. Patients aged >75 years have become the fastest growing population initiating dialysis. These patients have increased comorbid diseases and functional limitations which affect mortality and quality of life. This review describes the challenges of dialysis initiation and considerations for management of the elderly subpopulation. There is a need for an integrative approach to care, which addresses management issues, health-related quality of life, and timely discussion of goals of care and end-of-life issues. This comprehensive approach to patient care involves the integration of nephrology, geriatric, and palliative medicine practices.

Keywords: Dialysis, Palliative care, Elderly, Geriatrics, Hospice, Quality of life, Withdrawal from dialysis, Withold from dialysis, Conservative care, Mortality

Ms. DB is no stranger to the health care system. At 82-years old, she is regularly seen by her primary care physician for longstanding hypertension and poorly controlled diabetes. In addition to her medical problems, DB has also had a hip fracture and now relies on a cane to get around. She continues to live independently, although her family worries about her safety at home and her recent weight loss. DB’s medical problems have now focused on worsening renal function with accelerated declines in her glomerular filtration rate (GFR) (12 mL/min), which has prompted referral to nephrology.

DB was evaluated by a consulting nephrologist. She admits to poor appetite and decreased interest in community activities, which she blames on “getting old.” A physical examination reveals a frail appearing elderly woman with mild lower extremity swelling. Laboratory testing indicates advanced renal failure, with a low albumin and hemoglobin.

DB’s case is not straightforward, and such situations have become a common scenario for nephrologists. Chronic kidney disease has increasingly become a geriatric disease, with a dramatic rise in incidence within the aging population. One in 195 people in the United States aged >75 years have end-stage renal disease (ESRD).1,2 In comparison with those with normal renal function, the elderly patient with chronic kidney disease is more likely to have increased comorbidities, walking impairments, and decrements in quality of life. The difficult task the nephrologist faces is helping an elderly patient such as DB decide whether to initiate dialysis. Regardless of whether a dialysis is chosen, the nephrologist is faced with the dilemma of how best to attend to the patient’s burden of disease and suffering.

Elderly patients with advanced kidney disease carry a high mortality, regardless of whether dialysis is chosen or not. The annual mortality rate among dialysis patients in the United States is approximately 23%, with approximately 38% surviving 5 years.2 Mortality rates in dialysis patients aged 65 and older are six times higher than those in the general population. In a United States Renal Data System (USRDS) registry study, 1-year mortality for octogenarians and nonagenarians after dialysis initiation was 46%. Patients with 2 to 3 comorbidities had a 31% increased risk of death as compared with patients with no or fewer comorbidities.1

This review will examine the spectrum of renal disease in the elderly patient, beginning with discussions and decisions regarding dialysis initiation, continuing with a description of disease effect on quality of life, and concluding with care at end of life. The management paradigm addresses the effects of disease burden, including symptoms, quality of life, and issues surrounding goals of care. Future care of this growing population with chronic kidney disease will involve a personalized approach incorporating the patient, referring physician, and specialties such as geriatric and palliative care services.

The Spectrum of Disease

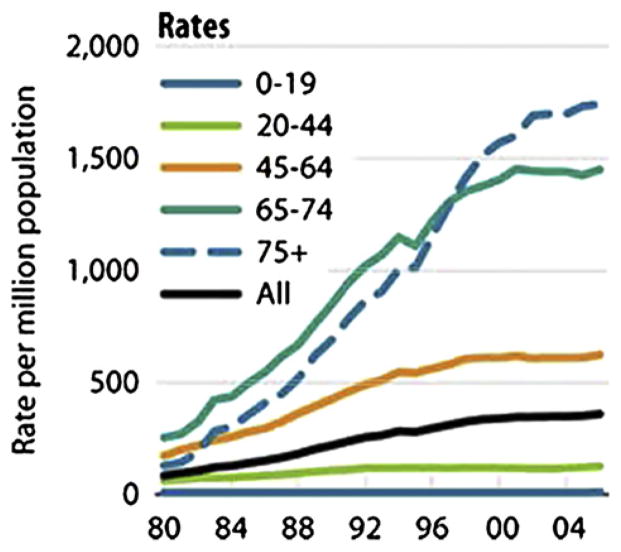

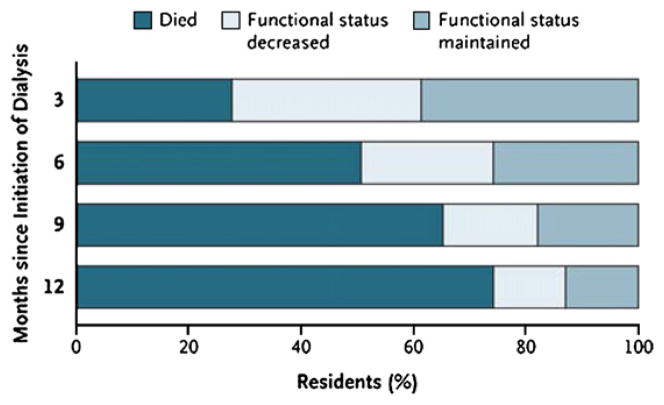

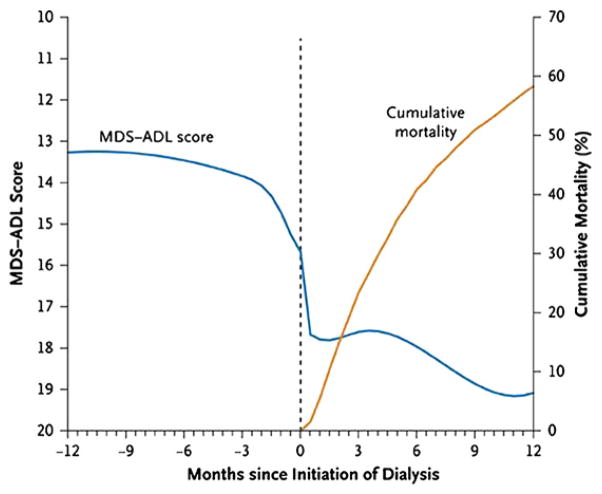

DB is representative of the fastest growing segment of the dialysis population. The rate of patients older than 75 initiating dialysis is nearly 2000 per million population, an increase of 11% since 2000 (Fig 1). The median age of patients starting dialysis from the 2008 USRDs data is 64.4 years, an increase from a median age of 56 years in 1986.2 However, rates of dialysis initiation continue to rise, and survival in elderly patients is markedly decreased, often with deficits in quality of life. In two recent studies of elderly patients initiating dialysis, survival was extremely poor (Fig 2), with a rapid decline in functional status before death (Fig 3).3,4

Figure 1.

The incident rate for those aged ≥75 years has grown 11% since 2000, to 1,744 per million population. Reproduced from U.S. Renal Data System (USRDS) 2008 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD, 2008.

Figure 2.

Change in functional status and death after initiation of dialysis in 549 nursing home residents. Reproduced with permission from Tamura MK, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Kristine Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE. NEJM 361:1539–1547, 2009.

Figure 3.

Smoothed trajectory of functional status before and after initiation of dialysis and cumulative mortality rate. Reproduced with permission from Tamura MK, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Kristine Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE, NEJM 361:1539–1547, 2009.

Elderly patients with advanced kidney disease share many of the same comorbidities as the ESRD population, including diabetes, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease, and peripheral vascular disease. These patients also have a higher risk for geriatric-specific syndromes. Within a cohort of 5888 patients aged ≥65 years, those with chronic kidney disease had a higher incidence of frailty, a syndrome based on five measures which identifies patients with reduced functional reserve who are at risk for functional decline, as compared with age-matched controls with normal kidney function.3

Detriments in physical function have been associated with poor outcomes. Recent USRDS data indicate that about 50% of patients new to dialysis who are aged >66 years have a disability ambulation, including 10% of patients who are entirely unable to walk.2 Dialysis initiation was associated with a functional decline that is independent of age, gender, race, and functional status before initiation in a nursing home registry. Twelve months after initiation, 58% of cohort had died and only 13% maintained predialysis functional status.4

Patients with chronic kidney disease often have poor outcomes after hospitalization and invasive procedures. Dialysis patients are at increased risk for sudden cardiac death, with significantly decreased survival (3%) at 6 months after hospitalization following cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR), compared with controls (9%).5 Patients with moderate chronic renal insufficiency have increased mortality after implantable cardioverter-defibrillator placement for ventricular arrhythmias.6 Outcomes after cardiac surgery are also worse in older patients with ESRD. In a retrospective analysis, patients had 3.9 times higher hospital mortality compared with other cardiac surgery patients without kidney disease (12.7% vs. 3.6%, P < .001).7 Not surprisingly, multivariate analysis found age greater than 70 years to be one of the independent predictors of hospital mortality. ESRD patients on hemodialysis (HD), especially diabetics, have been noted to have an increased prevalence of amputation because of peripheral vascular disease.8 These patients have high postoperative mortality; one study reporting 16% mortality within the ESRD population compared with 6% in patients with mild or no renal insufficiency.9

In summary, elderly patients with advanced kidney disease have a higher burden of illness with increased comorbidities, which puts them at higher risk for invasive procedures which may, in turn, negatively affect survival and quality of life. These sobering statistics highlight the need for careful consideration and honest conversations with patients regarding disease progression and management.

Health-Related Quality of Life

Elderly patients are also at risk for compromised health-related quality of life (HRQOL). HRQOL has been described as the extent to which one’s usual or expected physical, social, or emotional well-being is affected by a medical condition and/or its treatment. Patients with advanced kidney disease, including those who are not on dialysis, generally report impairment in a variety of HRQOL domains. These impairments are more striking for the physical as opposed to the mental or emotional domains. Importantly, reductions in HRQOL scores have been associated with decreased survival and increased hospitalizations.10 Elderly patients, in general, have more marked reductions in physical domains than younger patients.

Different aspects of HRQOL are significantly affected by the presence of kidney disease. Domains that may be more strikingly affected include cognitive impairment, depression, physical and social functioning, and physical symptoms specific to kidney disease, including dialysis treatment-related symptoms. Since assessment of HRQOL is now mandated by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, it will be important for providers to both assess and develop treatment plans for HRQOL problems. This is a challenge for the nephrology community and provides an opportunity for collaboration with geriatric and palliative care services whose focus is geared toward care of the complex elderly population and symptom management in chronic disease.

Depression is prevalent in ESRD and has been associated with poor outcomes. Hedayati and colleagues prospectively followed up 98 HD patients and on the basis of direct patient interviews identified about one-quarter as having clinical depression. A total of 80% of these depressed patients had died or were hospitalized at the time of follow-up, compared with nondepressed patients (43.1%), confirming other studies that suggest the existence of a strong relationship between depression and mortality.10–12 Importantly, depression is potentially treatable in the ESRD population using medications, exercise, or cognitive-behavioral therapy.13–15 Significant cognitive impairment is common, with >70% of HD patients noted to have moderate to severe cognitive impairment.16 Nephrologists commonly under-diagnose both depression and cognitive impairments.17

Pain is also prominent among the ESRD elderly population. It can be specific to the underlying disease causing kidney disease, such as diabetic neuropathy, or can be due to metabolic derangements, such as calciphylaxis. Other symptoms include pruritus, dry skin, restless legs, and nausea.18

Symptoms specific to dialysis treatment itself include postdialysis session fatigue. Lindsay and colleagues evaluated time to recovery in HD patients and found patients treated with standard thrice weekly treatments average about 6 hours to recover versus less than 1 hour in patients treated by short daily sessions or nocturnal HD. Improvements in recovery time associated with changes in the dialysis treatment regimen were correlated with improvement in HRQOL scores.19

HRQOL measures have been found to improve with treatment of other problems, such as anemia. A recent review of patients with chronic kidney disease emphasized that improvement in selected HRQOL domains, such as physical functioning, energy, and vitality, are associated with partial correction of anemia, especially within physical function domain.20

In contrast, the option for “life-sustaining” therapy such as dialysis may prove too onerous for certain high-risk patients. Attention should focus on the burdens of therapy and how the treatment itself affects one’s HRQOL. It needs to be determined whether patients and their families prefer more efforts be directed at achieving quality of life versus quantity of life.

Difficulties With Prognostication

Defining the high-risk patients can be challenging for nephrologists and other medical providers. DB and her physicians will struggle deciding whether the benefits of dialysis initiation outweigh the risks. Among patients already undergoing dialysis, it is important to identify chronically debilitated patients with a poor QOL who would benefit from palliative care interventions, including withdrawal from dialysis. Elderly patients, often with significant comorbidities, have increased risk for early death. The Charlson Comorbidity Index, which includes a composite score of age and multiple comorbidities, has been modified for ESRD patients and found to predict hospitalization and mortality.21 A prognostic score, based on low body mass index, comorbidities, and late referral to nephrology, has also been developed to identify elderly patients at increased risk for 6-month mortality after dialysis initiation. Among these patients, mortality rates ranged from 8% in low-risk group and 70% in the highest risk group.22

A simple prognostic instrument has been used to assess how well providers are at identifying ESRD patients who would benefit from palliative care services. The “Surprise Question” (SQ) inquires whether a provider would be surprised if a patient died over the next year. In one study, the mortality rate in the “no” group was 29.4% versus 10.6% in “yes” group (P = .032). The Charlson Comorbidity Index was additive as a predictor of mortality.23 Cohen and colleagues have integrated a modified SQ along with patient age, comorbid dementia, peripheral vascular disease, and decreased albumin to create a validated 6-month mortality model that may be applicable for both research and clinical purposes.24 In another study, patients reporting poor perceived health status had eight times greater mortality risks compared with those reporting excellent/very good self-reported health.25

Many providers have difficulty disclosing poor prognosis to patients. For a disease with a mortality rivaling cancer, frank discussions with patients and care providers should be the norm rather than the exception. Patients desire to know information about prognosis and survival data. In a questionnaire study of 100 patients referred to a nephrologist, the vast majority (97%) wanted to be given life-expectancy information, even if the news was bad. They also wanted the physician to disclose this information without having to be prompted.26 A recent survey of 584 Canadian stage 4 and 5 patients further demonstrates this need for prognostic information. Davison and colleagues revealed 60.7% of patients undergoing dialysis regretted their decision to start dialysis. In addition, 90.4% surveyed patients reported that their nephrologist had not discussed prognosis with them.27 This striking data highlight the need for improved communication regarding prognosis and disease progression. It should be noted that this population differs from the dialysis population in the United States, which has a broader racial and ethnicity; preferences and information needs may be different.28

Disclosing information regarding prognosis may have profound ramifications regarding patient decisions on dialysis initiation and kidney disease management. There is an increasing need for not only improved prognostication tools but also improved communication of prognosis and disease progression with patients. There have been interventions designed within other specialties which address life-limiting diseases and discussions of goals of care. The future will require incorporating these tools into the field of nephrology.29,30

Initiation Practices

DB’s presentation with advanced kidney disease to the nephrologist is not unusual in clinical practice. Patients are frequently started on dialysis without adequate pre-dialysis visits. They are often initiated using HD venous catheters rather than permanent access, such as a native fistula. These risk factors have been implicated as predictors of early mortality.10

Elderly patients are not exempted from this practice. In an observational study of US Medicare HD patients aged >67 years, 56.8% underwent dialysis through an HD catheter. One-year crude death rates were substantially higher in these patients at 41.5% compared with 24.9% in patients with native fistula.31 Another study found that 60.3% of very elderly patients (75 years and older) were considered as late referral (defined as nephrology evaluation less than 8 weeks before initiating dialysis) compared with 42.9% of nonelderly patients. These patients had statistically significant higher incidence of dialysis through HD catheter (69%) compared with nonelderly (45.6%)32 This lack of adequate referral further limits the opportunity for providers to build and maintain trust with patients which could further affect their understanding and goals of care planning.

The timing of referral and planned dialysis initiation has an effect on quality of life. Patients initiating dialysis in an early referral group from seven European countries had statistically higher hemoglobin levels and quality of life scores compared with late referrals. Higher quality of life scores in planned patients were found to be independent of factors such as comorbidity, emphasizing the benefits of a planned transition to dialysis.33

These statistics coupled with other predictors of early mortality serve to highlight the need for earlier evaluation and thoughtful planning for elderly patients with advanced kidney disease. In comparison with younger counterparts, elderly patients are more likely not to receive peritoneal dialysis (PD) despite relatively comparable infection and technique failure rates. PD may affect burden of disease by decreasing transportation difficulties to HD center and avoiding postdialysis fatigue common to patients after a HD session.34,35 These benefits, however, should be considered closely because reports suggest that caregivers of elderly patients undergoing PD experience significant burden and adverse effects on their quality of life.36

The appropriate timing of referral is often difficult for nonnephrology physicians. In a Dutch investigation, primary care physicians and nonnephrology specialists were less likely to refer patients to nephrologists than nephrologists were to accept patients for dialysis.37 Timely evaluation by a nephrologist, defined as adequate evaluation to allow for patient and family education, management, and preparation for dialysis, is associated with better outcomes. To accomplish this goal, improved referral guidelines are needed for primary care physicians. In addition, the need for open dialogue and communication between nephrologists and referring physicians is imperative for management of these patients.

Management: An Opportunity for Integrative Care

For many patients, kidney failure management frequently involves dialysis initiation that is often performed urgently, without adequate numbers of pre-dialysis visits, and conducted through catheters rather than permanent access. The mortality for these elderly patients is high, often with infectious complications and hospitalizations. In a retrospective analysis of hospitalized patients initiating dialysis, mean survival was 19 months for patients aged >75 years, and 29.4 months for those aged 65–74 years, compared with 52 months for those aged 50–65 years. Severity of comorbid conditions and functional capacity was more important in predicting survival and mortality in these patients than age alone.38 Furthermore, in a 12-month prospective study of incident dialysis patients aged 70 to 86 years, 29% patients died during the study period; mortality increased 2.8-fold in patients aged >80 years compared with 70–74 years, and 2.3-fold in patients with peripheral vascular disease.39

If patients, such as DB, had full disclosure to the risks and decrements in quality of life with dialysis initiation, other treatment plans including conservative management may become a more frequent occurrence. Within the same survey study by Davison and colleagues, surveyed patients reported a need for improved education regarding end-of-life care, pain and symptom management, and routine end-of-life care discussions.27 These patient preferences are important and may best be addressed through integrative care involving primary care, nephrology, and geriatric and palliative care services.

This close attention and management of patient’s clinical condition and quality of life is important as the benefits of early dialysis initiation in the elderly patients have been questioned.34 Many of these patients with advanced CKD will die than start dialysis, at any level of GFR, and are likely to have a slower progression of their CKD.35 This means that many elderly patients may survive with low GFRs and not require dialysis before a “natural” death. Starting dialysis may cause a rapid loss of residual renal function, with resulting adverse outcome.34 Strategies including very-low protein diet may be useful for those opting for conservative management or delaying dialysis initiation.40 Therefore, a concerted effort to maintain residual function and optimize symptoms and disease burden may be reasonable in elderly patients with advanced CKD.

Furthermore, there have been increasing studies describing the clinical course and outcomes for patients not opting for dialysis initiation, instead choosing maximum conservative treatment. These patients tend to be older, more likely to have diabetes, be functionally impaired, and have a higher number of comorbidities.41 Patients treated conservatively have a surprisingly longer survival than would be expected, often with substantially fewer hospitalizations than those treated with dialysis. In a prospective study of 73 patients (median age, 79 years) treated with non-dialytic management (mean GFR, 12 mL/min; range, 4–31), median life-expectancy was 1.95 years, with 65% 1-year survival. Sixty patients had no hospitalizations at all.42 Another observational study of elderly patients who opted for dialysis versus conservative treatment found patients in the latter group were more likely to die at home or in a hospice.43

In a comparison study involving the very old, 144 octogenarians (37 in conservative group and 107 in dialysis group) were followed up for survival. At 12 months, 99 patients died (68.7%), with median survival of 28.9 months in dialysis group as compared with 8.9 months in the conservative group. For octogenarians who chose dialysis, independent predictors of death within 1 year were poor nutritional status, later referral, and physical dependence.44 Another study which compared survival between patients aged >75 years treated conservatively versus dialysis, found that after adjustment for high comorbidities, such as ischemic heart disease, survival benefit in dialysis group was no longer detectable.45

Much of the research examining clinical outcomes for maximum conservative treatment has been conducted in Europe and has taken place in the context of interdisciplinary clinics with resources that include anemia treatment, nutrition, and frequent provider visits. This conservative, integrative care approach is the exception in the United States, in which patients are either referred late or in some cases not referred by their primary care physicians.46 Other US practices include conducting time-limited trials in high-risk patients and then discontinuing treatment if unsuccessful. The number of American elderly patients who elect not to start dialysis is unknown. For elderly patients with advanced kidney disease, interdisciplinary care including geriatric and palliative care services could potentially affect survival and quality of life, both in patients opting for dialysis and those for conservative therapy.

Withdrawal and End of Life

However, regardless of whether DB undergoes dialysis, her survival will be greatly influenced by her age and other comorbid conditions. Discussions regarding goals of care and advance care planning (ACP) ought to be common place for such patients. However, these discussions often are not performed and, when they are, they frequently occur in the setting of acute illness. This often leaves families and care givers in the difficult position of making these complex and life-and-death decisions. What should reasonably trigger and who should lead these conversations remain ill-defined; however, data demonstrate that patients expect these discussions to occur earlier and to be led by physicians.47

From 1990 to 1995, over 20,000 deaths were preceded by dialysis discontinuation.48 According to the USRDS 2008 report, 23.9% of patients discontinued dialysis in 2005–2006, and withdrawal of treatment is now the third leading “cause” of death.1 In France, a recent retrospective analysis found dialysis termination to be the most common “cause” of death.49 Factors associated with withdrawal include age and chronic disease, rather than acute causes such as infection, cardiovascular disease, and stroke.50

After dialysis discontinuation, patients typically live an average of 8 days. Retrospective analyses from family members and care providers of patients who withdrew identified pain and agitation as most common symptoms at end of life. Other prominent symptoms include myoclonus or muscle twitching, dyspnea, and gastrointestinal symptoms.51 Therapeutic options in these patients are more complicated with dosing adjusted for renal failure and advanced age.

To achieve a “good” death, one that addresses symptom management, patient considerations, and meaningful interactions with loved ones, hospice care best accomplishes this goal. However, hospice services are frequently underutilized. In a retrospective 2-year analysis of 115,239 deceased dialysis patients, 21.8% withdrew from dialysis and 13.5% used hospice. Patients who chose hospice were more likely to die outside the hospital at 22.9%, compared with 69% of non-hospice patients.52

Patients undergoing appropriate end-of-life care, including palliative and hospice services, have been noted to have satisfactory symptom management. In a prospective cohort study involving 79 patients, who underwent dialysis discontinuation and palliative care resources, 93% of family and caregivers felt treatment during the last 24 hours of life was effective.53

Advance directives, a component of ACP, are completed by only 6% to 35% of dialysis patients.54 In a study of patients’ perspectives regarding ACP, patients identified ACP as an essential part of their medical care, highlighting the desire to know their prognosis and what the future holds. Most importantly, these patients believed the physician should be responsible for initiating and guiding ACP discussions.

These results, along with the recent Medicare Conditions for Coverage requirement to address ACP in dialysis patients, highlight the need for improved guidance in provider-patient communication and discussions.47 Tools have also been established to assist with end-of-life care including Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment and End of Life protocols.

Clinician Tools and Future Direction

DB’s presentation is not unique. There are many thousands of elderly individuals with advanced kidney disease, complicated by multiple comorbidities, functional impairments, and poor quality of life. As providers, the task will be to direct the focus of treatment away from the disease toward a patient-centered approach.

There have been innovative approaches to caring for these patients. These include specialized geriatric rehabilitation units with on-site dialysis. Li and colleagues described the experience of 164 dialysis patients discharged to one of these specialized units. Unique features included shortened daily dialysis sessions to optimize therapy sessions and to decrease postdialysis fatigue. Both nephrology and geriatric specialties were on the plan of care team with weekly interdisciplinary meetings led by a nephrologist. Most patients achieved their rehabilitation goals.55 Other areas of interest include increasing use of modalities such as assisted PD.56

Elderly patients with advanced kidney disease, especially those with increased comorbidities, represent a high-risk group of patients with decreased survival. Their care should focus on the disease trajectory of chronic organ failure, which has been described as a slow progression with subtle loss of functional reserve after sentinel events such as hospitalization or acute illness.57 These clinical setbacks provide key opportunities to readdress goals of care and the need for palliative therapeutics. Through early conversations and attention to disease progression, transitions toward end-of-life, ACP, and bereavement opportunities can occur smoothly and contribute to patient, provider, and family satisfaction. In Table 1, we outline a suggested approach to elderly patients approaching ESRD.

Table 1.

Approach to the Elderly CKD Patient Approaching ESRD

|

This approach requires further improvements in education with curricula incorporating skills in communication, symptom management, and end of life issues. Tools to assess HRQOL in ESRD patients will assist with early detection. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have recently updated the Medicare Conditions for Coverage for nation’s dialysis centers to include annual assessments of HRQOL through the Kidney Disease Quality of Life-36 Survey. This update underscores the importance of HRQOL assessment in high risk patients. The next step will be to implement these assessments into clinical practice. Through the Renal Physicians Association and American Society of Nephrology, guidelines have been published with recommendations regarding dialysis initiation, withdrawal, and withholding in patients with limited life expectancy. Limited trials of dialysis to assess quality of life and acceptability by patients and care givers have been suggested. These guidelines also address conflict resolution when differences in goals of care exist between provider and patient/family members.58

Care of these patients is complex and should involve interdisciplinary teams, including geriatrics and palliative medicine. This will demand innovative approaches to CKD clinic structure and design. Improvements in earlier referral and comprehensive care including management of anemia, bone disease, and nutrition will also be important. Improved ability to identify and refer patients from primary care clinics is essential for timely management, including decisions regarding modality and access planning.

In conclusion, high-risk elderly patients often present to nephrology clinics and hospitals with advanced kidney disease. Many of these patients undergo dialysis initiation and then experience decreased survival and increased disease burden. These are sobering facts. Care providers must be prepared to travel the road less taken and adopt an integrative, individualized approach to elderly patients with kidney disease.

References

- 1.Kurella M, Covinsky KE, Collins AJ, et al. Octogenarians and nonagenarians starting dialysis in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:177–183. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-3-200702060-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.System USRD. USRDS 2008 Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shlipak MG, Stehman-Breen C, Fried LF, et al. The presence of frailty in elderly persons with chronic renal insufficiency. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:861–867. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, et al. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1539–1547. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moss AH, Holley JL, Upton MB. Outcomes of cardio-pulmonary resuscitation in dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1992;3:1238–1243. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V361238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wase A, Basit A, Nazir R, et al. Impact of chronic kidney disease upon survival among implantable cardioverter-defibrillator recipients. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2004;11:199–204. doi: 10.1023/B:JICE.0000048570.43706.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahmanian PB, Adams DH, Castillo JG, et al. Early and late outcome of cardiac surgery in dialysis-dependent patients: Single-center experience with 245 consecutive patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:915–922. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Combe C, Albert JM, Bragg-Gresham JL, et al. The burden of amputation among hemodialysis patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:680–692. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Hare AM, Feinglass J, Reiber GE, et al. Postoperative mortality after nontraumatic lower extremity amputation in patients with renal insufficiency. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:427–434. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000105992.18297.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradbury BD, Fissell RB, Albert JM, et al. Predictors of early mortality among incident US hemodialysis patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2:89–99. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01170905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hedayati SS, Bosworth HB, Briley LP, et al. Death or hospitalization of patients on chronic hemodialysis is associated with a physician-based diagnosis of depression. Kidney Int. 2008;74:930–936. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimmel PL, Peterson RA, Weihs KL, et al. Multiple measurements of depression predict mortality in a longitudinal study of chronic hemodialysis outpatients. Kidney Int. 2000;57:2093–2098. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wuerth D, Finkelstein SH, Finkelstein FO. The identification and treatment of depression in patients maintained on dialysis. Semin Dial. 2005;18:142–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2005.18213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ouzouni S, Kouidi E, Sioulis A, et al. Effects of intradialytic exercise training on health-related quality of life indices in haemodialysis patients. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:53–63. doi: 10.1177/0269215508096760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duarte PS, Miyazaki MC, Blay SL, et al. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy is an effective treatment for major depression in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2009;76:414–421. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray AM. Cognitive impairment in the aging dialysis and chronic kidney disease populations: An occult burden. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2008;15:123–132. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tyrrell J, Paturel L, Cadec B, et al. Older patients undergoing dialysis treatment: Cognitive functioning, depressive mood and health-related quality of life. Aging Ment Health. 2005;9:374–379. doi: 10.1080/13607860500089518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen LM, Germain M, Brennan M. End-Stage Renal Disease and Discontinuation of dialysis. In: Morrison RS, Meier DE, Capello CF, editors. Geriatric Palliative Care. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lindsay RM, Heidenheim PA, Nesrallah G, et al. Minutes to recovery after a hemodialysis session: A simple health-related quality of life question that is reliable, valid, and sensitive to change. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:952–959. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00040106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leaf DE, Goldfarb DS. Interpretation and review of health-related quality of life data in CKD patients receiving treatment for anemia. Kidney Int. 2009;75:15–24. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beddhu S, Bruns FJ, Saul M, et al. A simple comorbidity scale predicts clinical outcomes and costs in dialysis patients. Am J Med. 2000;108:609–613. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00371-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Couchoud C, Labeeuw M, Moranne O, et al. A clinical score to predict 6-month prognosis in elderly patients starting dialysis for end-stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:1553–1561. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moss AH, Ganjoo J, Sharma S, et al. Utility of the “surprise” question to identify dialysis patients with high mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:1379–1384. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00940208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen LM, Ruthazer R, Moss AH, et al. Predicting six-month mortality for patients who are on maintainance hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:72–79. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03860609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thong MS, Kaptein AA, Benyamini Y, et al. Association between a self-rated health question and mortality in young and old dialysis patients: A cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2008;52:111–117. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fine A, Fontaine B, Kraushar MM, et al. Nephrologists should voluntarily divulge survival data to potential dialysis patients: A questionnaire study. Perit Dial Int. 2005;25:269–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: Perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:195–204. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05960809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cukor D, Kimmel PL. Education and end of life in chronic kidney disease: Disparities in black and white. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:163–166. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09271209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barclay JS, Blackhall LJ, Tulsky JA. Communication strategies and cultural issues in the delivery of bad news. J Palliat Med. 2007;10:958–977. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.9929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evans WG, Tulsky JA, Back AL, et al. Communication at times of transitions: How to help patients cope with loss and re-define hope. Cancer J. 2006;12:417–424. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200609000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xue JL, Dahl D, Ebben JP, et al. The association of initial hemodialysis access type with mortality outcomes in elderly Medicare ESRD patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:1013–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.ajkd.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwenger V, Morath C, Hofmann A, et al. Late referral–A major cause of poor outcome in the very elderly dialysis patient. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:962–967. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfk030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caskey FJ, Wordsworth S, Ben T, et al. Early referral and planned initiation of dialysis: What impact on quality of life? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:1330–1338. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Afolalu B, Finkelstein SH, Finkelstein FO. How can the outcomesin elderly dialysis patients be improved? Semin Dial. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hiramatsu M. How to improve survival in geriatric peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int. 2007;27(Suppl 2):S185–S189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belasco A, Barbosa D, Bettencourt AR, et al. Quality of life of family caregivers of elderly patients on hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:955–963. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Visser A, Dijkstra GJ, Huisman RM, et al. Differences between physicians in the likelihood of referral and acceptance of elderly patients for dialysis-Influence of age and comorbidity. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:3255–3261. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chandna SM, Schulz J, Lawrence C, et al. Is there a rationale for rationing chronic dialysis? A hospital based cohort study of factors affecting survival and morbidity. BMJ. 1999;318:217–223. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7178.217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lamping DL, Constantinovici N, Roderick P, et al. Clinical outcomes, quality of life, and costs in the North Thames Dialysis Study of elderly people on dialysis: A prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2000;356:1543–1550. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brunori G, Viola BF, Parrinello G, et al. Efficacy and safety of a very-low-protein diet when postponing dialysis in the elderly: A prospective randomized multicenter controlled study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:569–580. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.02.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith C, Da Silva-Gane M, Chandna S, et al. Choosing not to dialyse: Evaluation of planned non-dialytic management in a cohort of patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephron Clin Pract. 2003;95:c40–c46. doi: 10.1159/000073708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong CF, McCarthy M, Howse ML, et al. Factors affecting survival in advanced chronic kidney disease patients who choose not to receive dialysis. Ren Fail. 2007;29:653–659. doi: 10.1080/08860220701459634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carson RC, Juszczak M, Davenport A, et al. Is maximum conservative management an equivalent treatment option to dialysis for elderly patients with significant comorbid disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1611–1619. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00510109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Joly D, Anglicheau D, Alberti C, et al. Octogenarians reaching end-stage renal disease: Cohort study of decision-making and clinical outcomes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:1012–1021. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000054493.04151.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, et al. Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1955–1962. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sekkarie MA, Moss AH. Withholding and withdrawing dialysis: The role of physician specialty and education and patient functional status. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;31:464–472. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v31.pm9506683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davison SN. Facilitating advance care planning for patients with end-stage renal disease: The patient perspective. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1023–1028. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01050306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leggat JE, Jr, Bloembergen WE, Levine G, et al. An analysis of risk factors for withdrawal from dialysis before death. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:1755–1763. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V8111755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Birmele B, Francois M, Pengloan J, et al. Death after withdrawal from dialysis: The most common cause of death in a French dialysis population. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:686–691. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hackett AS, Watnick SG. Withdrawal from dialysis in end-stage renal disease: Medical, social, and psychological issues. Semin Dial. 2007;20:86–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-139X.2007.00249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cohen LM, Germain MJ, Poppel DM, et al. Dying well after discontinuing the life-support treatment of dialysis. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2513–2518. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.16.2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Murray AM, Arko C, Chen SC, et al. Use of hospice in the United States dialysis population. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:1248–1255. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00970306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cohen LM, Germain M, Poppel DM, et al. Dialysis discontinuation and palliative care. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36:140–144. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2000.8286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holley JL, Nespor S, Rault R. The effects of providing chronic hemodialysis patients written material on advance directives. Am J Kidney Dis. 1993;22:413–418. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)70144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li M, Porter E, Lam R, et al. Quality improvement through the introduction of interdisciplinary geriatric hemodialysis rehabilitation care. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50:90–97. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reddy NC, Korbet SM, Wozniak JA, et al. Staff-assisted nursing home haemodialysis: Patient characteristics and outcomes. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1399–1406. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lorenz KA, Lynn J, Dy SM, et al. Evidence for improving palliative care at the end of life: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:147–159. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moss AH. A new clinical practice guideline on initiation and withdrawal of dialysis that makes explicit the role of palliative medicine. J Palliat Med. 2000;3:253–260. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2000.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]