Abstract

Background

Parathyroid hormone (PTH) levels are often measured after thyroid surgery and are used to detect patients at risk for postoperative hypoparathyroidism. However, there is a lack of consensus in the literature about how to define the recovery of parathyroid gland function and when to classify hypoparathyroidism as permanent. The goals of this study were to determine the incidence of low postoperative PTH in total thyroidectomy patients and to monitor their time course to recovery of parathyroid gland function.

Methods

We identified 1054 consecutive patients who underwent a total or completion thyroidectomy from 1/2006 to 12/2013. Low PTH was defined as a PTH measurement <10 pg/mL immediately after surgery. Patients were considered to be permanently hypoparathyroid if they had not recovered within 1 year. Recovery of parathyroid gland function was defined as PTH ≥10 pg/mL and no need for therapeutic calcium or activated vitamin D (calcitriol) supplementation to prevent hypocalcemic symptoms.

Results

Of 1054 total thyroidectomy patients, 189 (18%) had a postoperative PTH <10 pg/mL. Of those 189 patients, 132 (70%) showed resolution within 2 months of surgery. Notably, 9 (5%) resolved between 6–12 months. At 1 year, 20 (1.9%) were considered to have permanent hypoparathyroidism. Surprisingly, 50% of those patients had recovery of PTH levels yet still required supplementation to avoid symptoms.

Conclusions

Most patients with a low postoperative PTH recover function quickly, but it can take up to 1 year for full resolution. Hypoparathyroidism needs to be defined not only by PTH levels, but also by medication requirements.

Introduction

Iatrogenic injury of the parathyroid glands is an unintended consequence of total thyroidectomy. Measuring the serum PTH immediately after surgery is a sensitive and specific method of assessing the function of the parathyroid glands and for identifying patients at risk for hypocalcemia [1–4]. If the postoperative PTH level is low, then administering calcium and activated vitamin D (calcitriol) can reduce the incidence of symptomatic hypocalcemia [5–10].

The incidence of a low postoperative PTH after total thyroidectomy has been highly variable in the literature, ranging between 7% [11] to 37% [1]. Part of this variability is related to the variety of methods used to define this complication [6]. Since surgeons know that this is a potential risk of surgery, many patients are empirically treated with either calcium or calcitriol to try and avoid symptoms. While this supplementation can help minimize symptoms for patients, it makes it difficult to determine who truly has transient hypoparathyroidism and who does not based only on calcium levels, symptoms, or the need for supplementation. One objective measure, and possibly the cleanest method for defining transient hypoparathyroidism, is to look at the PTH level immediately after surgery before beginning any supplementation. In this study, we considered anyone with a PTH <10 pg/mL to have transient hypoparathyroidism.

The majority of patients with parathyroid dysfunction after thyroidectomy return to normal function within a few weeks or 1 month of surgery [12, 13]. However, there is a lack of consensus in the literature about how to best define the recovery of parathyroid gland function. Some studies consider patients to be euparathyroid as soon as their serum PTH levels recover to at least 10 pg/mL in the absence of hypocalcemic symptoms [12, 14]. Others focus on medication administration, so recovery of parathyroid gland function is considered when the patient no longer requires therapeutic calcium or calcitriol supplementation to prevent symptoms of hypocalcemia [15, 16]. A third way to define recovery of parathyroid gland function is to determine when the serum PTH measurement is in the normal range and cessation of calcium or calcitriol supplementation occurs [2, 11, 17].

Furthermore, different time points have been used to determine when postoperative hypoparathyroidism should be classified as permanent. Some consider postoperative parathyroid gland injury to be permanent if recovery of function has not occurred within 6 months [2, 11, 16, 18–20] while others define permanence at 1 year after surgery [15, 17].

The incidence of a low PTH following total thyroidectomy is highly variable. When a low PTH is found after surgery, it is also not clearly elucidated what that will mean to the patient in the long-term. When can they anticipate recovery, and what are the chances that they will end up with permanent hypoparathyroidism? The goals of this study were to determine the incidence of low postoperative PTH in patients who underwent total thyroidectomy and to monitor their time course to recovery of parathyroid gland function.

Methods

We performed a retrospective review of the prospectively collected Endocrine Surgery Database at the University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics. Between January 2006 and December 2013, 1133 patients underwent total thyroidectomy or completion thyroidectomy at the University of Wisconsin. 1054 patients had their serum PTH levels measured within 24 hours of surgery and were included in this study. The PTH assay performed at our center has a normal range of measurement between 10 and 72 pg/mL. Low PTH was defined as a PTH measurement <10 pg/mL immediately after surgery.

Patients were followed for 1 year. We determined that recovery of parathyroid gland function had occurred when the serum PTH was ≥10 pg/mL AND the patient did not require calcitriol or >2000 mg of daily calcium supplementation to avoid symptoms of hypocalcemia. Patients were considered to be permanently hypoparathyroid if they had not recovered completely within 1 year.

Stata version 11 (Stata Corporation; College Station, TX) statistical software was used to analyze the data. Characteristics of patients with a low postoperative PTH were compared to patients with postoperative PTH ≥10 pg/mL using t-tests and χ2 tests. In a similar manner, patients with transient hypoparathyroidism were compared to patients with permanent hypoparathyroidism. Multivariate logistic regression modeling was performed to identify independent risk factors for low postoperative PTH and for permanent hypoparathyroidism. Finally, time to event analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method for all the patients with low PTH to determine time to resolution, using the date of complete recovery as the outcome. For this analysis, 5 patients were censored for missing laboratory data or missing information about symptoms or medications at their last follow up visit. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value <0.05.

Results

Of 1054 total thyroidectomy patients, 189 (18%) had postoperative PTH <10 pg/mL. Patients with low PTH were compared to patients with a postoperative PTH measurement ≥10 pg/mL (Table 1). The majority of patients in each group were female and they were of similar ages. Patients with postoperative PTH <10 pg/mL had lower preoperative PTH measurements. In addition, a larger percentage of patients with low postoperative PTH underwent additional procedures such as a central neck dissection, modified radical neck dissection, or parathyroid gland autotransplantation during their thyroidectomy. Patients with PTH <10 pg/mL after surgery also had a higher incidence of parathyroid tissue identified on their final pathology report, suggesting inadvertent removal of parathyroid tissue.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics: postoperative PTH <10 pg/mL compared to PTH ≥10 pg/mL.

| Variable | PTH <10 pg/mL (n = 189) | PTH ≥10 pg/mL (n = 865) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 44.9 ± 18.1 | 46.7 ± 16.7 | 0.19 |

|

| |||

| Female, % | 84.1 | 78.2 | 0.07 |

|

| |||

| Operation, % | 0.40 | ||

| total thyroidectomy | 96.8 | 95.5 | |

| completion thyroidectomy | 3.2 | 4.5 | |

|

| |||

| Central neck dissection, % | 14.3 | 8.8 | 0.02 |

|

| |||

| Modified radical neck dissection, % | 10.1 | 5.8 | 0.03 |

|

| |||

| Parathyroid autotransplantation, % | 31.2 | 14.0 | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Hyperthyroidism, % | 27.0 | 25.2 | 0.61 |

|

| |||

| Thyroiditis, % | 30.2 | 26.9 | 0.37 |

|

| |||

| Malignancy, % | 33.3 | 32.7 | 0.87 |

|

| |||

| Incidental malignancy, % | 9.0 | 10.5 | 0.53 |

|

| |||

| Parathyroid tissue present on pathology report, % | 25.4 | 13.0 | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Preoperative PTH, pg/ml, mean ± SD | 42.8 ± 24.3 | 48.0 ± 26.3 | 0.03 |

|

| |||

| Preoperative calcium, mg/dl, mean ± SD | 9.2 ± 0.4 | 9.3 ± 1.8 | 0.64 |

|

| |||

| Postoperative Diagnosis, % | 0.67 | ||

| cancer | 34.4 | 32.5 | |

| thyroiditis | 37.5 | 35.4 | |

| benign | 26.5 | 29.3 | |

| other | 1.6 | 2.9 | |

Time to Resolution of Low Postoperative PTH

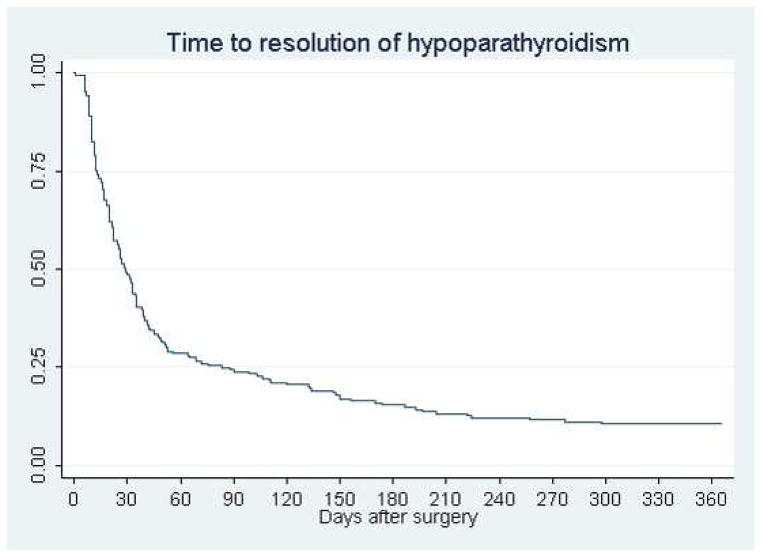

Next we examined the time course of recovery of the 189 patients with low postoperative PTH (Figure 1). The majority of the patients showed a rapid recovery of their parathyroid function. 132 (70%) showed resolution within 2 months of surgery, and 49 of these patients had recovered within 1–2 weeks of surgery. Of those patients with hypoparathyroidism at 2 months after surgery, 28 (49%) resolved by 6 months after surgery. Interestingly, an additional 9 (16%) resolved between 6 months and 1 year.

Figure 1.

Time to resolution of hypoparathyroidism.

Incidence of Permanent Hypoparathyroidism

At 1 year, 20 patients were considered to have permanent hypoparathyroidism due to the need for ongoing supplementation. 50% of these patients had recovery of PTH levels to ≥10 pg/mL yet still required supplementation to avoid symptoms of hypocalcemia. While their PTH level was officially in the normal range of the laboratory, it was inadequate to meet their bodies’ needs and they still had symptoms of hypocalcemia. The permanently hypoparathyroid group represents 11% of patients with initial postoperative PTH <10 pg/mL and 1.9% of the entire cohort of patients undergoing thyroidectomy.

Risk Factors for Low Postoperative PTH and Permanent Hypoparathyroidism

Patients with low postoperative PTH who showed recovery of parathyroid gland function within one year were compared to patients with permanent hypoparathyroidism (Table 2). Patients with parathyroid gland function recovery had lower preoperative PTH measurements. Permanently hypoparathyroid patients had lower 2 week calcium levels and a higher incidence of parathyroid tissue identified in the thyroid specimen on final pathology report.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics of cohort with postoperative PTH <10 pg/mL: transient hypoparathyroidism compared to permanent hypoparathyroidism.

| Variable | Transient Hypoparathyroidism (n = 169) | Permanent Hypoparathyroidism (n = 20) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 44.6 ± 17.9 | 47.1 ± 19.4 | 0.57 |

|

| |||

| Female, % | 85.8 | 70.0 | 0.07 |

|

| |||

| Operation, % | 0.07 | ||

| total thyroidectomy | 97.6 | 90.0 | |

| completion thyroidectomy | 2.4 | 10.0 | |

|

| |||

| Central neck dissection, % | 14.2 | 15.0 | 0.93 |

|

| |||

| Modified radical neck dissection, % | 8.9 | 20.0 | 0.12 |

|

| |||

| Parathyroid autotransplantation, % | 30.2 | 40.0 | 0.37 |

|

| |||

| Hyperthyroidism, % | 29.0 | 10.0 | 0.07 |

|

| |||

| Thyroiditis, % | 29.0 | 40.0 | 0.31 |

|

| |||

| Malignancy, % | 31.4 | 50.0 | 0.10 |

|

| |||

| Incidental malignancy, % | 8.9 | 10.0 | 0.87 |

|

| |||

| Parathyroid tissue present on pathology report, % | 23.1 | 45.0 | 0.03 |

|

| |||

| Preoperative PTH, pg/ml, mean ± SD | 41.1 ± 23.2 | 60.3 ± 29.3 | 0.01 |

|

| |||

| Preoperative calcium, mg/dl, mean ± SD | 9.2 ± 0.4 | 9.0 ± 0.4 | 0.17 |

|

| |||

| First postoperative PTH measurement was undetectable, % | 37.3 | 55.0 | 0.13 |

|

| |||

| 2 week follow-up calcium, ml/dl, mean ± SD | 8.9 ± 1.3 | 7.7 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Postoperative Diagnosis, % | 0.37 | ||

| cancer | 32.5 | 50.0 | |

| thyroiditis | 38.5 | 30.0 | |

| benign nodular goiter | 27.8 | 15.0 | |

| other | 1.2 | 5.0 | |

On multivariate logistic regression modeling, we found that patients who received autotransplantation of parathyroid tissue during surgery were more likely have low PTH immediately after surgery (OR = 2.6; 95% CI, 1.8–3.8). In addition, patients with the identification of parathyroid tissue on final pathology report, suggesting inadvertent removal of parathyroid tissue, were more likely to be have postoperative PTH <10 pg/mL (OR = 2.2; 95% CI, 1.5–3.3). The only independent risk factor for permanent hypoparathyroidism was parathyroid tissue on pathology report (OR = 3.6, 95% CI, 1.1–11.5). Age, gender, neck dissection, thyroiditis, and malignancy were not independently associated with low postoperative PTH or permanent hypoparathyroidism. The validity of this multivariate logistic regression model was tested using the likelihood ratio chi-square test, and the p-value for the model was 0.03.

Discussion

Iatrogenic injury of the parathyroid glands resulting in low postoperative PTH levels is a common complication of total thyroidectomy. In our study, 18% of patients had a postoperative PTH <10 pg/mL, but the majority of these patients showed recovery of parathyroid gland function within 2 months of surgery. Only 1.9% of the entire cohort was considered to have permanent hypoparathyroidism as indicated by the ongoing need for calcium or calcitriol supplementation 1 year after surgery.

The 18% incidence of a low postoperative PTH in this study falls within the transient hypoparathyroidism incidence range of 7% [11] to 37% [1] that has been reported in the literature. This variability in incidence can be attributed to the varying definitions used to classify patients as being transiently hypoparathyroid following total thyroidectomy. Thomusch et al. assumed postoperative hypoparathyroidism when calcium or vitamin D therapy was required to treat clinical symptoms of tetany, but serum lab values were not considered [11]. This study’s definition failed to include asymptomatic patients who could have had a serum PTH <10 pg/mL, and this could account for the low reported incidence rate of 7%. McCullough et al. performed a study in which they calculated the incidence of low postoperative PTH using the same definition as our study, but their calculated incidence of 37% [1] was much higher than this study’s incidence of 18%. However, McCullough et al. had a sample size of only 72 patients while this study included 1054 total thyroidectomy patients.

Permanent hypoparathyroidism is most commonly defined as failure of the parathyroids to regain normal function by 6 months after surgery. Interestingly, 5% of patients with low postoperative PTH resolved 6–12 months after surgery in our study. For this reason, we decided that 1 year was the most appropriate time point for defining permanent hypoparathyroidism, which 1.9% of total thyroidectomy patients developed in our study. Using an earlier time point could result in classifying some patients as permanently hypoparathyroid when they could still show resolution of their condition. For example, Chow et al. found that 2.8% [2] of patients developed permanent hypoparathyroidism, as defined at 6 months after surgery, even though this study used the same criteria for parathyroid gland function recovery as our study.

Other differences seen in the rate of permanent hypoparathyroidism in different studies is in part due to the discrepancy in definitions that were used in order to determine recovery of parathyroid gland function. To exemplify, Al Dhari et al. defined recovery as a serum PTH ≥10 pg/mL in the absence of hypocalcemic symptoms [14]. However, Nawrot et al. defined recovery as cessation of calcium and calcitriol supplementation [17]. Our study considered both PTH levels AND medication administration, so a patient would only be euparathyroid once they no longer had symptoms or required supplemental calcium or calcitriol in addition to having a serum PTH ≥10 pg/mL. Given our stringent definition, our rate of permanent hypoparathyroidism was 1.9%. If we had only used PTH levels to define permanent hypoparathyroidism, our rate would have been only 0.9%. We also found that by 1 year, patients had determined how much calcium or calcitriol they needed to avoid symptoms, and most did not complain of any symptoms of hypocalcemia. Therefore, it is important to not only ask about their symptoms but to examine medication lists as well.

Our investigation also examined risk factors for parathyroid gland complications after total thyroidectomy. We found that the only independent risk factor for developing permanent hypoparathyroidism was parathyroid tissue present on pathology report, which indicated inadvertent removal of parathyroid tissue. Age, gender, neck dissection, thyroiditis, hyperthyroidism, and malignancy were not independently associated with low postoperative PTH or permanent hypoparathyroidism, which is likely a reflection of the fact that the surgeons involved in this study were all high-volume surgeons with experience operating on higher risk patients.

It is interesting to note that on bivariate analysis, the patients who developed permanent hypoparathyroidism had an average preoperative PTH that was higher than the transiently hypoparathyroid patients (60.3 pg/mL vs. 41.1 pg/mL p=0.01). However, both of these measurements fall within the normal PTH range, suggesting that this difference is probably not clinically significant. It is possible that these patients were more likely to have Vitamin D deficiency pre-operatively causing this higher average PTH, but since Vitamin D levels are only clinically indicated when PTH levels are above the normal range, most patients did not have this data available to analyze. Post-operatively patients were all treated with Vitamin D supplementation; so long term any baseline pre-operative Vitamin D deficiency should have been corrected for.

There are a few limitations to this study. First, it should be noted that this was a retrospective study. Still, we utilized an institutional database that was prospectively collected. In addition, the data was collected from a single university hospital, so it may be subject to institutional bias. Nevertheless, due to the large study sample including 1054 patients, it is likely that these results can be generalized to a larger population. Also, at the institution where this study was performed, patients are supplemented with calcium and calcitriol based on their serum PTH measurements after surgery. Some of these patients may not necessarily need supplementation in order to prevent hypocalcemic symptoms. Therefore, we could not accurately examine the incidence of symptomatic transient hypoparathyroidism. Finally, the time to resolution of parathyroid gland function is directly proportional to how often PTH levels are measured. As time passes after surgery, lab tests and clinic visits become more spaced out, so the reported time to recovery could be longer than the true time to recovery.

In conclusion, low serum PTH is a common occurrence after total thyroidectomy, but the vast majority of patients showed parathyroid gland function recovery within 2 months of surgery. Only 1.9% of patients undergoing total thyroidectomy developed permanent hypoparathyroidism, defined by a serum PTH <10 pg/mL or the need to continue calcium or calcitriol supplementation to prevent hypocalcemic symptoms 1 year after surgery. In the literature, there is a wide range of reported incidences of transient and permanent postoperative hypoparathyroidism. A consensus needs to be reached about how to best define these complications. This study suggests that medication administration needs to be considered in addition to PTH measurements since 50% of patients with permanent hypoparathyroidism had recovery of PTH levels to ≥10 pg/mL, yet still required supplementation to avoid symptoms of hypocalcemia. Furthermore, 12 months may be the most appropriate time point for defining hypoparathyroidism as permanent since 5% of patients with low postoperative PTH resolved 6–12 months after surgery.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the University of Wisconsin Department of Surgery, the T35DK062709 NIH training grant, and the Shapiro Summer Research Program for funding.

Footnotes

Summary of Author Contributions.

Ritter-Conception/Design, Data Collection, Analysis/Interpretation, Writing

Elfenbein-Conception/Design, Analysis/Interpretation, Critical Revision

Schneider-Data Collection, Critical Revision

Chen-Data Collection, Critical Revision

Sippel-Conception/Design, Data Collection, Analysis/Interpretation, Critical Revision

Disclosures.

No disclosures to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McCullough M, Weber C, Leong C, Sharma J. Safety, efficacy, and cost savings of single parathyroid hormone measurement for risk stratification after total thyroidectomy. Am Surg. 2013;79:768–774. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chow TL, Choi CY, Chiu AN. Postoperative PTH monitoring of hypocalcemia expedites discharge after thyroidectomy. Am J Otolaryngol. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fahad Al-Dhahri S, Al-Ghonaim YA, Sulieman Terkawi A. Accuracy of postthyroidectomy parathyroid hormone and corrected calcium levels as early predictors of clinical hypocalcemia. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;39:342–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rivere AE, Brooks AJ, Hayek GA, Wang H, Corsetti RL, et al. Parathyroid hormone levels predict posttotal thyroidectomy hypoparathyroidism. Am Surg. 2014;80:817–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Youngwirth L, Benavidez J, Sippel R, Chen H. Postoperative parathyroid hormone testing decreases symptomatic hypocalcemia and associated emergency room visits after total thyroidectomy. Surgery. 2010;148:841–844. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.07.038. discussion 844–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edafe O, Antakia R, Laskar N, Uttley L, Balasubramanian SP. Systematic review and meta-analysis of predictors of post-thyroidectomy hypocalcaemia. Br J Surg. 2014;101:307–320. doi: 10.1002/bjs.9384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reeve T, Thompson NW. Complications of thyroid surgery: how to avoid them, how to manage them, and observations on their possible effect on the whole patient. World J Surg. 2000;24:971–975. doi: 10.1007/s002680010160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alhefdhi A, Mazeh H, Chen H. Role of postoperative vitamin D and/or calcium routine supplementation in preventing hypocalcemia after thyroidectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncologist. 2013;18:533–542. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carter Y, Chen H, Sippel RS. An intact parathyroid hormone-based protocol for the prevention and treatment of symptomatic hypocalcemia after thyroidectomy. J Surg Res. 2014;186:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carr AA, Yen TW, Fareau GG, Cayo AK, Misustin SM, et al. A single parathyroid hormone level obtained 4 hours after total thyroidectomy predicts the need for postoperative calcium supplementation. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomusch O, Machens A, Sekulla C, Ukkat J, Brauckhoff M, et al. The impact of surgical technique on postoperative hypoparathyroidism in bilateral thyroid surgery: a multivariate analysis of 5846 consecutive patients. Surgery. 2003;133:180–185. doi: 10.1067/msy.2003.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Youngwirth L, Benavidez J, Sippel R, Chen H. Parathyroid hormone deficiency after total thyroidectomy: incidence and time. J Surg Res. 2010;163:69–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sitges-Serra A, Ruiz S, Girvent M, Manjón H, Dueñas JP, et al. Outcome of protracted hypoparathyroidism after total thyroidectomy. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1687–1695. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Dhahri SF, Mubasher M, Mufarji K, Allam OS, Terkawi AS. Factors Predicting Post-thyroidectomy Hypoparathyroidism Recovery. World J Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2571-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almquist M, Hallgrimsson P, Nordenström E, Bergenfelz A. Prediction of Permanent Hypoparathyroidism after Total Thyroidectomy. World J Surg. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00268-014-2622-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karamanakos SN, Markou KB, Panagopoulos K, Karavias D, Vagianos CE, et al. Complications and risk factors related to the extent of surgery in thyroidectomy. Results from 2,043 procedures. Hormones (Athens) 2010;9:318–325. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nawrot I, Pragacz A, Pragacz K, Grzesiuk W, Barczyński M. Total thyroidectomy is associated with increased prevalence of permanent hypoparathyroidism. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:1675–1681. doi: 10.12659/MSM.890988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfleiderer AG, Ahmad N, Draper MR, Vrotsou K, Smith WK. The timing of calcium measurements in helping to predict temporary and permanent hypocalcaemia in patients having completion and total thyroidectomies. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91:140–146. doi: 10.1308/003588409X359349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erbil Y, Barbaros U, Işsever H, Borucu I, Salmaslioğlu A, et al. Predictive factors for recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy and hypoparathyroidism after thyroid surgery. Clin Otolaryngol. 2007;32:32–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2007.01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ozbas S, Kocak S, Aydintug S, Cakmak A, Demirkiran MA, et al. Comparison of the complications of subtotal, near total and total thyroidectomy in the surgical management of multinodular goitre. Endocr J. 2005;52:199–205. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.52.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]